The trade in rhinos goes back a long way due to a long association with medicine and demand for the exotic.

By Lalita Kaplish

Digital Content Editor

Wellcome Trust

Poison Detector

The ancient Persians of the 5th century BCE thought that vessels carved from rhino horn could be used to detect poisoned drinks, – a belief that persisted into the 18th and 19th centuries among the royal courts of Europe.

There may be some truth behind the rhino horn’s ability to detect poisons. Rhino horns are composed largely of the protein keratin, also the chief component in hair, fingernails, and animal hooves. Many poisons are strongly alkaline, and may have reacted chemically with the keratin in rhino horn cups.

A Taste for the Exotic

Perhaps the most famous rhinoceros to reach Europe in modern times came from India in 1515 as a gift for King Manuel I of Portugal. The German artist Albrecht Dürer carved a woodcut of the rhino apparently based on sketches and descriptions of this animal. ‘Dürer’s Rhinoceros’ became the enduring image of a rhinoceros in Western culture for centuries, despite some anatomical inaccuracies (notably the small horn protruding from its shoulder).

The British public had a chance to see a rhinoceros in 1684 thanks to a commercial venture by some East India merchants. The rhino was offered for sale at £2000, but the exporters failed to find a buyer and ended up exhibiting the rhino themselves in London at “twelve pence a piece” (Clarke, 1986).

“A Very strange Beast called a Rhynoceros lately brought from the East-Indies, being the first that ever was in England, is daily to be seen at the Bell Savage Inn on Ludgate-Hill, from Nine a Clock in the Morning til Eight at Night.”

Advertisement in then ‘London Gazette’ 16 October 1684

The rhinoceros already had strong medical associations in Europe by the 17th century. The London Society of Apothecaries, featured ‘Dürer’s Rhinoceros’ on its crest as early as 1617, along with Apollo, the god of healing, killing the dragon of disease.

By the 19th century there was a flourishing trade in exotic animals in London. An 1879 article in the magazine ‘Good Words’ gives the prices of rhinos available from the shop of Charles Jamrach, “the most famous and internationally patronised provider of exotic animals in England, if not Europe” (Simons, 1988): a Sumatran rhinoceros cost £1000, and an Indian rhinoceros, Begum, not yet priced had been purchased from British officers in Burma at £1250. Despite the disreputable nature of the exotic animal trade, the London elites who visited Jamrach’s shop knew that if they wanted something, Jamrach would get it for them – if the price was right.

Objects of Desire

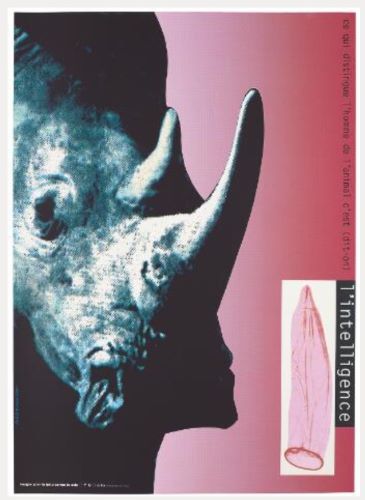

The common association of rhino horns with virility is usually attributed to traditional Chinese medicine, but there is no evidence that rhino horn was ever recommended as an aphrodisiac in Chinese medicine. How this myth arose is unclear, the suggestive shape of the rhino horn might have had something to do with it. What ever the source, it is a myth that persists in Western culture, as this French AIDS poster shows:

Rhino horn is associated with manhood in Yemen, where it was traditionally used for the handles of curved daggers called janbiya, presented to Yemeni boys at age 12. Rhino horn is highly prized as a material for its lustre. In China, the ornamental use of rhino horn for cups and other items dates back to at least the 7th century CE.

Chinese Medicine

Rhino horn is used in traditional medicine systems in many Asian countries to cure a variety of ailments. In traditional Chinese medicine, the horn, which is shaved or ground into a powder and dissolved in boiling water, is used to treat fever, rheumatism, gout, and other disorders. Elixirs for fevers and liver problems were first prescribed in traditional Chinese medicine more than 1,800 years ago.

Overall there isn’t much evidence to support the claims about the healing properties of the horns. And as a result of raised awareness about the plight of the rhino, horn powder was removed from the traditional Chinese pharmacopeia in the 1990s, reducing demand to some extent.

East Meets West

Around 2008, the greatest demand for rhino horn came from Vietnam – the result of a curious mix of medical myths about its potency. And a Western myth about its aphrodisiac properties that travelled East.

A familiar pattern of an elite in pursuit of the rare and exotic emerges. The powdered horn was seen as a party drug and virility enhancer – a luxury item for the wealthy. It was also prized as a way to drink more alcohol and cure hangovers (because of its use in liver cures).

A pervasive rumour also swept the country in the mid-2000s that drinking rhino horn powder had cured a Vietnamese politician of cancer. This curious rumour persists although there’s no basis for using rhino horn to treat cancer in either scientific or traditional Chinese medicine.

With rhino horn going for as much as $100,000 per kilogram in Vietnam in the past few years, the temptation for poachers and illegal traders in Africa and Asia is irresistible. If the rhino is to be saved, then the demand for rhino horn needs to be confronted.

Originally published by Wellcome Library, 05.06.2016, under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.