The earliest forms of democratic governments began to form in Greek city-states in the sixth century BCE.

By Ildemaro Gonzalez

The dêmos [people] are lord here, taking turns

In annual succession, not giving too much to the rich,

Even a poor man has a fair or equal share.

Athenian Playwright c. 400 BCE

Political philosopher Hannah Arendt claims, “Freedom is the raison d’être [purpose of existence] of politics” (Arendt 153). Mankind needs government in order to establish security and safeguard people’s personal freedoms. Yet, for the majority of recorded history, mankind has been governed by autocracies, in which the few control the lives of the many and restrict the freedom of the poor to expand the freedom of the wealthy. To resolve this disparity, there must be an integration of all citizenry into government, for people cannot be free if they are forced to obey laws that they had no say in making. This is the importance of having a public sphere, where the people can make their voices heard and play a role in politics.

Democracy is founded on this principle of equality among men—a principle which also explains the nearly universal appeal of democracy since its appearance in the eighteenth century in the American Revolution. Yet, that enlightened and novel concept of democracy was discovered nearly two thousand years earlier by ancient Athens, the first democracy. Why did the original idea of democracy develop here, and how did it function in its nascent context?

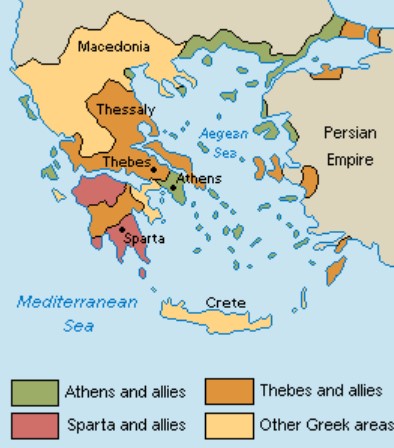

The earliest forms of democratic governments began to form in Greek city-states in the sixth century BC, and were well established by the fifth century BC. Prior to the transient era of democracy, many Greek city-states were governed by archons, or magistrates, on the council of Areopagus. It was during the sixth century BC that the polis (the citizen body) of a few city-states grew tired of being “enslaved” by the upper class and their tyrant rulers and forced structural reforms in the governing bodies towards a more democratic system. These initial democracies, however, were only democracies insofar as the citizens were able to elect their governing leaders from the elite class. The idea of a people freely governing itself did not come about until the early fifth century, when the term demokratia (power in the hands of the people) was coined (O’Neil 34).

Ancient Athens is regarded as the quintessential direct democracy, but this did not happen instantly; rather, it was the result of gradual political reforms that extended over hundreds of years. At the turn of the sixth century BC, Athens was recovering from a period of internal conflict caused by class warfare that led to succession of tyrannical rulers for half a century. In this primarily agricultural and merchant Athens, the people were in a state of general serfdom. The Athenian working class was outraged; they were being forced to pay exorbitant taxes, and those who could not pay were enslaved to pay off their debt to the upper class. They had no representation and no power in government whatsoever. The Athenians realized that this lack of political representation violated their freedom, and that balance of power among classes was necessary to allow for the liberty of the public. This was a founding democratic principle that Solon (590-561 BC), the premier archon in 590 BC, enforced when the Athentian polis protested and reached out to him for change, ultimately laying the foundation for the first democracy.

The primary goals of Solon’s pseudo-democracy were to alleviate the imbalance of power among the classes and eliminate any inclination towards tyranny. This Solonian Athens hated tyranny more than anything else, and in order to uphold a concept of freedom among the polis this administration had to keep the power among the citizens, not any one man or faction. As Hannah Arendt explains, “wherever the man-made world does not become the scene for action and speech—as in despotically ruled communities which banish their subjects into the narrowness of the home and thus prevent the rise of a public realm—freedom has no worldly reality” (Arendt 147). Athens’s working class had been denied freedom both by debt enslavement and by denial of power or representation in the governing of their city. To be free in their society, people need a “scene for action and speech”, because if they cannot voice their concerns and have the power to address them then the people are forced to yield to the will of those who do hold that power, and that is tyranny.

In his new administration, Solon established a three-part system of government over Athens and the metropolitan area of Attica: an Ecclasia (the Assembly), a Boule (the Council of 400), and the council of the Areopagus. He also divided the citizens into four classes, distinguished by income. Only the upper class, the pentakosiomedimnoi, could serve as archons on the council of Areopagus, but they had to be elected by Athens’s tribes. The council of Areopagus still maintained “guardianship of the laws” like it had prior to Solon’s reforms, but some of their other powers were redistributed. The Areopagus did gain the power to formally review officials before they entered office (dokimasia) and the power to hold them accountable for their actions by punishment and fines (euthya). This served as an important check to the magistrates in office, so tyrants would not emerge. Solon’s Council of 400 consisted of 100 members from each Athenian tribe, and their primary function was to screen the business and agenda to be discussed in the Assembly, where the citizens generated policy (Starr 8-9).

Solon abolished the practice of enslavement to pay off debts, ameliorating the economic position of the lower class and curbing the power of the wealthy. An importantly democratic trademark of Solon’s reforms was the establishment of heliaea, the Popular law-courts. Here the thetes (lower class) could serve as jurors, and anyone could sue on behalf of the wronged and appeal against wrongdoings of the archons. It was also important for Solon that the thetes be admitted to the Assembly, where the polis discussed and voted on policy, however it was unrealistic that many thetes could afford to take days off from working to participate in Assembly. Solon’s reforms were great political strides towards democracy, but “Solon himself was no democrat, not that the concept had yet appeared” (Starr 9). Solon remained skeptical of the citizenry, being careful not to entrust the people with too much power, and this is where Solon’s Athens lacked complete democracy. The stepping-stones were in place, however, for the rise of an exceptional democracy.

After Solon’s reforms, Athens saw an increase in commerce along with new regional tensions, and the need for more centralized management led to the tyranny of Pisistratus and his sons in 561 BC. This reign lasted until 510 BC, when the exiled Athenian leaders recruited the Spartans to help oust the tyrants and restore the aristocracy. Sequentially, Isagoras was elected archon eponymos (chief archon), but then tried to eliminate Solon’s Council of 400 in order to neutralize the Assembly. The enraged Athenians rose up against this treachery and “with the battle cry of isonomia or equal rights” executed Isagoras and his supporters (Starr 13).

Following this political turmoil, Cleisthenes (510-507 BC), an aristocratic leader whose clan was exiled by Isagoras, sought to reestablish control by enacting democratic reforms to gain the public’s approval. Cleisthenes divided the Attica into 10 tribes. Each sent 50 members drawn by lot to his new Council of 500, which scrutinized the concerns brought before the Assembly and voted on a preliminary proposal (probouleuma) or general statement to place on the agenda of the Assembly. From then on, the tribes held equal representation in the councils and courts. Cleisthenes set one-year term limits for archons and also instituted the process of ostraka (ostracism) so that feared or disliked politicians could be exiled for ten years, as “a permanent measure against would-be tyrants” (Starr 16). During this reformation period, the Assembly also decided to keep stone record of their decrees, and change the selection of archons from election to lottery out of candidates nominated per district.

The implementation of the lottery system in selection of public officers was an ingenious measure to guarantee equal representation of the classes and prevent corruption. The use of elected representatives in government is not a fully democratic political practice. Athenians found that men seeking election were generally upper class elites, who were focused on winning votes for the power. To check the power of the wealthy, Athenians filled their representative bodies (i.e. the Council of 500, the Popular Court, the Areopagus) by lottery, with an equal number of citizens from the ten tribes. This ensured that these bodies would be representative of the entire citizen body, endowing the entire citizenry with the freedoms of government participation and representation. At this point the thetes were allowed in all of these positions except the council of the Areopagus, to which they were granted access in later reforms. Only select positions were actually decided by election, but the assembly had the power to recall these elected officials (generals, financial managers), motivating them to work productively and honestly (Woodruff 26-27).

After Cleisthenes’s reforms, a war with Persia erupted around 490 and continued to 479 BC. Athens won many inspiring victories, and it was evident that the Athenian army and navy were more powerful because their men believed they were fighting for their own democracy and for their own freedom, not for the will of a monarch. During this time, however, the council of Areopagus capitalized on the fact that most of the men were off at war to expanded its powers, “tightening” the constitution in an effort to create a more oligarchic regime. In response, Ephialtes (478-461 BC) led a group of reformers to reduce the powers of the Areopagus for their misconduct. The council of Areopagus was diminished so they could only conduct trials for homicide and lesser transgressions, while the power to review archons entering the Areopagus and hold them accountable for their actions was distributed to the Council of 500 and the Popular Courts. In an important democratic measure, to allow for the unhindered participation of the thetes in their government, the Athenian democracy started giving wages to men serving in the governing bodies and allowed the thetes to be appointed archons (Woodruff 48-49).

The Athenian Assembly was the voice of the citizenry and in it laid the majority of the political power of Athens, but it took a considerable amount of time for Athens to fully integrate their lower class into the government. The Assembly consisted of the first 6,000 men to show up that day, and originally more men would have to be gathered each morning to fill up the seats, but when pay was instituted this ceased to be a problem. Athens was able to recognize that at the time, only the rich could work in government because they had the leisure time to do so, whereas the working class could not afford to involve itself in government without any compensation. Until pay was introduced, the thetes could never experience the freedom of being a full citizen because “without a politically guaranteed public realm, freedom lacks the worldly space to make its appearance” (Arendt 147). The lower class could not afford to attend Assembly prior to these reforms, and thus they did not have the freedom to contribute to their own government; they had no voice in the policymaking, but were subject to the policy regardless. The addition of pay for civil service, especially in the Assembly, dissolved these barriers and allowed for true democracy to stand in Athens.

The Assembly is the icon of Athenian democracy, but the existence of an assembly was common in ancient Greece even preceding early democracy. Most of these assemblies voted on policy, but voting in and of itself is not democratic by nature. What was unique about Athens was the freedom of speech and proposition. In Athens, any adult male citizen could speak at the Assembly, unlike Sparta’s pseudo-democracy where the assembly could only vote on matters presented by the kings and magistrates who reserved the right to speak. Voting in Sparta could not be considered democratic because the citizens had no say over what would be put up to a vote, and had no control over the policies they were given. If a tyrant tells a group that they must vote between all being slaves for him or all being killed, he cannot afterwards say that the people democratically decided to be his slaves.

Freedom of speech in the Assembly was a vital instrument for democracy and freedom to in Athens because “freedom needed, in addition to mere liberation, the company of other men who were in the same state, and it needed a common public space to meet them—a politically organized world, in other words, into which each of the free men could insert himself by word and deed” (Arendt 147). It was necessary for the everyday Athenian to have the opportunity to contribute to government because democracy is power in the hands of the people. People create governments in order to have security, but moreover, “freedom…is actually the reason that men live together in political organization at all” because we need security to go about our everyday lives freely (Arendt 145). When a government becomes despotic we say less government equals more freedom, but similarly, no government equals no freedom because amidst anarchy there is no security and no one to see to the preservation of freedom.

Hannah Arendt wrote, “Freedom as a demonstrable fact and politics coincide and are related to each other like two sides of the same matter” and it is evident the Athenians were the first to realize this (Arendt 147). Athenian democracy was the first to prioritize the freedom of the public and acknowledge that for this to be a reality there must be equal representation and distribution of power among the population. Only when everyone can participate in governing can a government truly guarantee freedom for all its citizens. Now, it is overtly hypocritical that the Athenians fought so ardently for political freedom while blatantly denying that same freedom and representation to slaves, women, and immigrants; in denying them these rights they were themselves tyrants, subjecting a people to their rules while refusing to give them any representation or power in the government under which they lived. It took over two thousand years, however, for this flaw to be addressed by any major government throughout the world, so it is hard to say that they should have known better, especially since it took almost as long for mankind to rediscover democracy after the fall of Athens.

Athenian democracy even at its peak was not perfect, not that any democracy ever has been. What Athens got right, however, were the ideas of demokratia and isonomia, concepts thousands of years ahead of their time. In a world where autocracy was the prevailing form of government, Athens realized the self-evident truths of liberty and equality and challenged the power imbalance of their oppressive regime. Athenian democracy was the birth of the public sphere and political freedom for the people, the same freedom that Americans fought for, crying, “give me liberty or give me death!” In his Rights of Man, Thomas Paine even acknowledges hopefully, “What Athens was in miniature America will be in magnitude” (23). Political freedom can only truly be realized in a government by the people and for the people; it was Athens that gave life to this democratic ideal, and it was with Athens in mind that this ideal was reborn and thrives to this day.

References

- Arendt, Hannah. Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought. New York: Penguin, 1978.

- O’Neil, James L. The Origins and Development of Ancient Greek Democracy. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1995.

- Paine, Thomas. Rights of Man: Part the Second, Combining Principle and Practice. The second edition. London: Printed for J.S. Jordan, 1792.

- Starr, Chester G. The Birth of Athenian Democracy: The Assembly in the Fifth Century B.C. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Woodruff, Paul. First Democracy: The Challenge of an Ancient Idea. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Originally published by The Stanford Freedom Project, republished with permission for edcuational, non-commercial purposes.