The history of Mesopotamian scribal culture reveals that repetition is not the enemy of civilization but one of its enabling conditions.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Writing Lost Its Mystery

In the earliest centuries of Mesopotamian civilization, writing carried an aura of danger and sanctity that far exceeded its practical utility. To inscribe signs into clay was not merely to record information but to participate in an act believed to stabilize the cosmos itself. Writing mediated between gods and kings, between memory and authority, between the fleeting present and an ordered past. The earliest texts were bound to ritual, divination, and royal power, and their production was limited to a small, highly trained elite. Scribes were not conceived as creative individuals but as custodians of an inherited order, entrusted with preserving words whose legitimacy derived from tradition rather than authorship. In this context, writing remained rare, slow, and deeply symbolic, its value inseparable from its scarcity.

By the second millennium BCE, however, this aura had begun to thin. Scribal schools multiplied alongside expanding bureaucratic states, and writing became an indispensable tool of governance, law, ritual maintenance, and prediction. Apprentices filled tablets with the same lexical lists, omen sequences, hymns, and legal formulas again and again, sometimes copying a single model dozens of times. What had once been exceptional became routine. Writing did not disappear into banality, but it entered a new phase in which repetition replaced revelation as its dominant mode, and endurance mattered more than originality.

This transformation generated unease precisely because it altered the relationship between knowledge and human judgment. If writing could be reproduced endlessly, what distinguished wisdom from formula. If knowledge resided in standardized texts rather than lived memory, did it still belong to the human mind, or had it migrated into archives that outlasted experience itself. Critics worried not simply that writing would weaken memory, but that it would detach understanding from practice. A tablet could be copied accurately without comprehension, transmitted faithfully without reflection. Knowledge, in this view, risked becoming inert. Preserved too well, it threatened to harden into patterns that could be repeated mechanically, obeyed without interpretation, and revered without being truly inhabited.

Yet this moment was not a cultural collapse. It was a reorientation. Mechanical reproduction did not extinguish creativity but redirected it. Interpretation, commentary, recombination, and mastery of tradition became the new measures of intellectual achievement. The Mesopotamian scribal world thus offers an early case study in a recurring human fear: that when knowledge scales, meaning will vanish. History suggests otherwise. What changes is not whether culture survives, but how it is made.

The Scribal Schools: Training Memory through Repetition

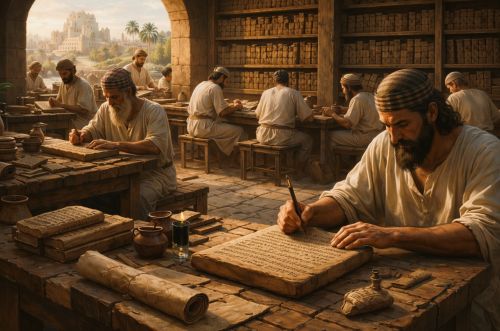

By the second millennium BCE, scribal education in Mesopotamia had become a formalized and demanding process centered on the edubba, the tablet house. These institutions were not schools in the modern sense but sites of disciplined cultural reproduction, where knowledge was transmitted through endurance, imitation, and correction. Entry into scribal life required years of labor, often beginning in childhood, and success depended less on inspiration than on stamina. The goal was not originality but reliability. A competent scribe was one who could reproduce authoritative forms without deviation, ensuring that texts remained legible, recognizable, and legitimate across time and space.

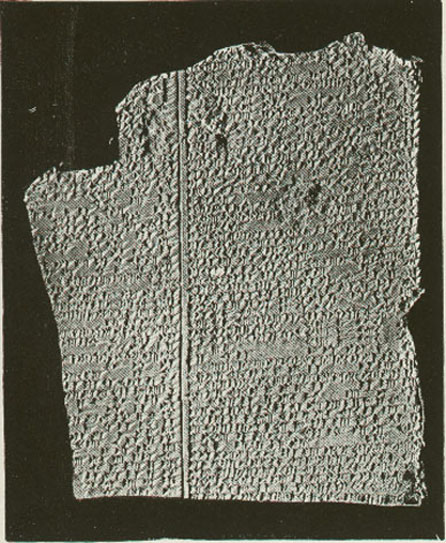

The curriculum of the scribal schools reflected this priority. Students began with basic sign lists and syllabaries, copying them repeatedly until the physical act of writing became automatic. From there, they progressed to lexical lists that categorized the world into ordered sequences: animals, professions, stones, plants, cities, gods. These lists were copied endlessly, not because novelty was expected, but because mastery emerged through repetition. To know a term was to recognize its place within an inherited structure. Memory was trained not as spontaneous recall but as patterned recognition embedded in the hand as much as the mind.

Correction played a central role in this process and shaped the intellectual character of the scribe. Tablets recovered from archaeological contexts often preserve the marks of instruction: overwritten signs, marginal notes, erased wedges, and model texts placed beside student copies. Error was neither stigmatized nor ignored. It was the medium through which conformity to tradition was achieved. Through repeated correction, the apprentice internalized not only proper forms but also the criteria by which writing itself was judged authoritative. Precision, consistency, and obedience to precedent became intellectual virtues, reinforced daily through supervised labor. Scribal discipline thus operated as a moral economy of knowledge, teaching students how to submit to inherited standards before they were permitted to transmit them.

Far from producing passive minds, this system cultivated a particular kind of intelligence. Repetition trained long-term memory, attention to detail, and sensitivity to variation within constraint. A skilled scribe learned to recognize subtle differences between similar formulas, to detect errors in copied texts, and to apply standardized language appropriately across genres. The apparent monotony of copying concealed a sophisticated cognitive discipline, one that privileged internalization over improvisation. Knowledge was not consumed but absorbed, becoming second nature through bodily practice.

Scribal repetition appears less as mechanical labor than as deliberate cultural conditioning. The scribal schools did not aim to produce thinkers detached from tradition but interpreters deeply embedded within it. Their graduates became the custodians of law, ritual, administration, and memory precisely because they had been trained to think through inherited forms rather than against them. Repetition did not erase judgment. It prepared the ground on which judgment could operate, ensuring that innovation, when it occurred, remained legible within a shared symbolic world. The authority of Mesopotamian knowledge depended not on originality but on continuity, and the scribal schools were the institutions that made such continuity possible across generations.

Standardization and Authority: Why Formula Mattered

As Mesopotamian societies expanded in scale, population, and territorial reach, standardization became not merely convenient but essential to governance. Formulaic writing allowed law, ritual, and administration to function across distance and time without constant renegotiation or reinterpretation. Legal clauses, royal titles, omen sequences, and administrative phrases were not ornamental repetitions but instruments of coordination in a world where oral clarification was often impossible. Their authority rested precisely on their predictability. A standardized text could be recognized as legitimate regardless of who copied it, where it circulated, or when it was read. In this sense, formula was not a constraint imposed on meaning but the condition that made shared meaning durable across generations, offices, and regions.

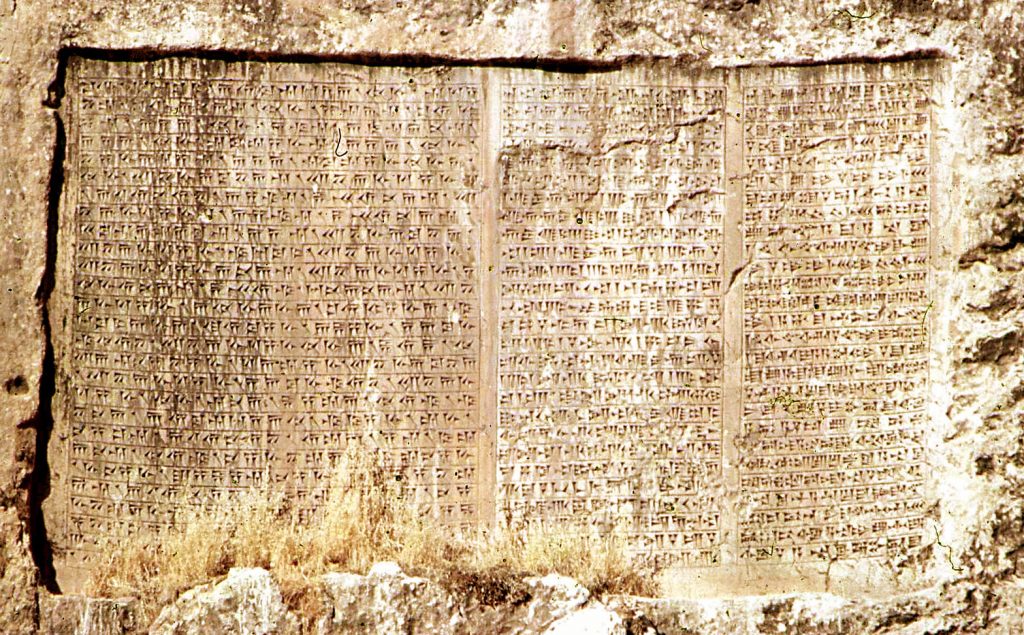

Law provides a particularly clear example of this logic. Legal documents relied on fixed phrasing to ensure that judgments were understood as extensions of precedent rather than expressions of personal will. Contracts, court records, and law collections used inherited verbal structures that linked individual cases to an established legal order. Authority flowed not from the creativity of the scribe but from the visible continuity of language itself. A clause repeated accurately signaled that justice was being administered within a recognized framework, insulating decisions from charges of arbitrariness or innovation. Formula thus functioned as a stabilizing force, binding present judgment to past practice and limiting the disruptive potential of individual discretion.

The same dynamic shaped religious and divinatory texts. Omen lists, incantations, and hymns depended on exact reproduction because their efficacy was believed to reside in proper form as much as content. A miswritten sign could invalidate a ritual or distort a prediction. Standardization here was not bureaucratic but cosmological. Repetition preserved alignment between human practice and divine order. The scribe’s task was therefore not to reinterpret the gods but to transmit their established language faithfully, reinforcing the idea that authority originated outside individual judgment and beyond temporal change.

Royal inscriptions reveal how formula also stabilized political legitimacy in an environment of frequent upheaval. Kings presented themselves through inherited titles, epithets, and narrative structures that connected each reign to an enduring tradition of rule. By repeating established formulas, rulers positioned themselves within a continuous lineage of authority, even amid conquest, rebellion, or dynastic rupture. Innovation occurred primarily in circumstance and emphasis rather than structure. The formula remained intact while events shifted around it. In this way, standardization did not resist historical change but absorbed it, translating novelty into recognizable forms. Authority endured not because it was unchanging, but because it was repeatedly reasserted through language that signaled continuity in the face of transformation.

The Ancient Anxiety: Knowledge without Living Memory

As writing became increasingly standardized and embedded in the daily operations of Mesopotamian society, unease grew about what this transformation meant for human memory and judgment. Knowledge that once circulated through oral transmission, apprenticeship, and lived practice now resided in tablets that could outlast their creators and circulate far beyond their original contexts. Critics feared that writing displaced memory rather than strengthening it, encouraging reliance on external marks instead of cultivated understanding. When wisdom could be consulted rather than recalled, it risked becoming passive, something accessed mechanically rather than enacted through experience. The concern was not that writing preserved too little, but that it preserved too much, allowing knowledge to survive without the interpretive labor that once gave it meaning.

At the heart of this anxiety was the distinction between knowing and copying. Scribal training made it possible to reproduce texts with remarkable accuracy even when comprehension lagged behind execution. A student could copy an omen list, hymn, or legal formula flawlessly without grasping its implications or limits. This raised the troubling possibility that cultural authority might migrate from judgment to replication. Texts could circulate independently of the wisdom that once animated them, becoming objects of obedience rather than understanding. Knowledge, critics feared, might harden into form, preserved perfectly yet hollowed of the practical reasoning that made it useful in lived situations.

This fear also reflected a broader concern about the erosion of context. Oral transmission embedded knowledge within relationships, performance, gesture, and situational nuance. Writing abstracted knowledge from these settings, fixing it into portable and repeatable forms that could be detached from their original circumstances. Once separated, texts could be interpreted without guidance, applied rigidly, or invoked without sensitivity to social or moral conditions. The tablet remembered everything, but it could not discriminate. Living memory, by contrast, was adaptive and selective, shaped by experience, correction, and judgment. The anxiety was not that writing forgot too much, but that it remembered indiscriminately, flattening difference and nuance in the name of preservation.

Yet these anxieties reveal less about the failure of writing than about the difficulty of adjusting to its power. Mesopotamian culture did not abandon memory; it redefined it. Scribal expertise came to involve not only recall but interpretation, mediation, and contextual application. Living memory did not disappear but shifted upward, residing in trained elites who navigated between fixed texts and lived realities. The fear that writing would hollow out wisdom proved unfounded. Instead, it forced societies to renegotiate where knowledge lived, how it was authorized, and who was trusted to give it meaning.

Creativity after Invention: Interpretation over Originality

The consolidation of scribal culture did not extinguish creativity so much as relocate it. Once foundational genres were standardized, intellectual labor shifted away from invention and toward interpretation. Scribes worked within inherited textual frameworks, but this constraint created space for a different form of creativity, one grounded in mastery rather than novelty. To understand a text meant knowing how it related to other texts, how it could be applied in varying circumstances, and how its authority could be sustained through careful transmission. Creativity emerged not from producing something unprecedented, but from engaging tradition with precision and judgment.

This interpretive creativity was especially visible in commentary traditions. Scribes annotated, glossed, and reworked existing texts, clarifying obscure passages, resolving ambiguities, or reconciling contradictions within inherited corpora. These interpretive layers did not displace authoritative texts but accumulated alongside them, forming dense textual ecosystems in which meaning was negotiated rather than declared. Commentary functioned as a mode of intellectual conversation across generations, allowing later scribes to engage earlier authorities without challenging their legitimacy. Even the act of copying itself could be interpretive, as choices about spacing, emphasis, correction, or omission reflected an understanding of textual structure and priority. What appeared to be mechanical reproduction often concealed subtle acts of judgment that shaped how texts were read and applied.

Genre formation further illustrates this dynamic. Many Mesopotamian literary, legal, and scholarly forms depended explicitly on earlier models and gained authority through visible continuity with them. Omen series expanded through accretion rather than replacement, incorporating new observations into established sequences. Legal reasoning relied on analogy and precedent, situating new disputes within familiar verbal frameworks. Hymns and prayers reworked inherited formulas to address changing political, ritual, or theological circumstances. In each case, originality was measured not by deviation but by appropriateness. A successful text was one that fit seamlessly into an existing system while extending its capacity to address new conditions. Creativity took the form of recombination, selection, and contextual refinement rather than rupture.

This model challenges modern assumptions that equate creativity with radical novelty. In the scribal world, authority and imagination were not opposites but interdependent. Interpretation required deep familiarity with tradition, and tradition provided the raw material for intellectual labor. The scribes of Mesopotamia demonstrate that cultural vitality does not depend on constant invention ex nihilo. It depends on the capacity to sustain meaning across time by reworking what already exists. Creativity, in this sense, was not diminished by repetition. It was structured by it, disciplined by it, and ultimately made possible through it.

Mechanical Knowledge and the Long History of Cultural Fear

The anxieties that accompanied Mesopotamian scribal culture were not unique to the ancient world. They belong to a recurring pattern in the history of knowledge, one that surfaces whenever information becomes easier to reproduce, store, or transmit at scale. Each expansion of intellectual infrastructure has generated fears that human judgment would be displaced by mechanism, that skill would give way to procedure, and that meaning would dissolve into repetition. What appears at first as a crisis of creativity is more accurately a crisis of trust: a concern about whether knowledge can remain vital when it is no longer scarce, guarded, or difficult to obtain. When access expands, societies are forced to confront uncomfortable questions about authority, expertise, and the value of human mediation in systems increasingly capable of operating without it.

This pattern reappeared with the spread of alphabetic literacy, when philosophers worried that writing would weaken memory and produce learners who possessed information without understanding. It resurfaced with the rise of bureaucratic states, where standardized documents threatened to replace situational judgment with rigid rule-following. The invention of print intensified these fears dramatically, as texts could now be reproduced on a scale unimaginable in earlier eras, circulating beyond traditional centers of learning and control. Critics warned that the flood of books would overwhelm discernment, flatten intellectual hierarchy, and encourage passive consumption rather than disciplined study. Each moment framed its anxiety in moral or cultural terms, yet the underlying concern remained consistent: that mechanical reproduction would sever knowledge from wisdom and replace judgment with mere access.

What these episodes share is not evidence of cultural decline but of cultural transition. New technologies reorganize how knowledge is accessed, evaluated, and transmitted, often faster than social norms can adapt. As information becomes more widely available, older gatekeeping mechanisms weaken, and new ones emerge, sometimes unevenly or imperfectly. Expertise shifts from possession of content to mastery of navigation, interpretation, and contextual application. Mechanical knowledge does not eliminate judgment; it relocates the sites where judgment matters most. The fear lies in the interval between these shifts, when inherited standards no longer align with emerging practices and authority appears unmoored.

Importantly, such anxieties often mistake scale for shallowness. The expansion of archives, libraries, and textual corpora does not inherently reduce meaning. Instead, it multiplies the conditions under which meaning must be negotiated. The challenge is no longer remembering everything but deciding what matters, how texts relate to one another, and when established forms must be adapted to new circumstances. Mechanical reproduction increases the volume of available knowledge, but it also increases the demand for interpretive labor. Far from making thought obsolete, it raises the stakes of thinking well.

Mesopotamian scribal culture stands at the beginning of a long historical arc rather than as an isolated anomaly. The fear that repetition would hollow out culture has accompanied every major expansion of intellectual technology, yet culture has persisted, reshaped rather than erased. Each transition has required societies to renegotiate authority, expertise, and creativity, often amid sharp resistance and moral panic. Mechanical knowledge does not end culture. It forces culture to justify itself, to articulate why judgment, interpretation, and responsibility still matter in a world where information can be endlessly reproduced without understanding.

Generative AI and the Return of the Scribal Problem

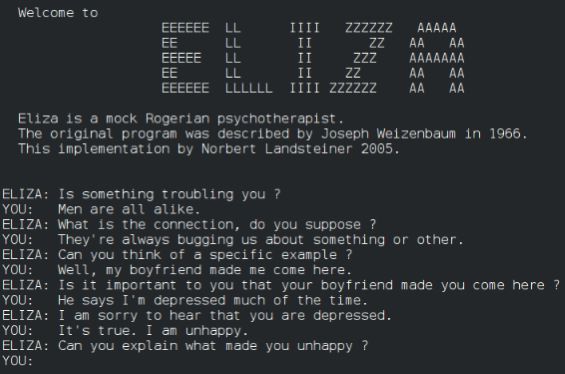

The emergence of generative artificial intelligence has revived, almost verbatim, the ancient anxieties once directed at scribal culture. Trained on vast corpora of existing texts, these systems produce language by identifying patterns, recombining structures, and predicting likely continuations. Critics argue that such outputs lack originality, intention, or lived understanding, reducing knowledge to imitation rather than insight. The charge is familiar. Like the Mesopotamian apprentice copying omen lists, the machine appears to reproduce without comprehension, raising fears that meaning has been severed from human judgment and reduced to mechanical procedure.

At the center of this concern lies the question of authorship and authority. If texts can be generated without experience, reflection, or accountability, what distinguishes wisdom from plausible noise. Skeptics worry that generative models blur the boundary between understanding and appearance, producing outputs that sound knowledgeable while remaining fundamentally hollow. This anxiety extends beyond aesthetics into ethics and governance. When language can be produced at scale without responsibility, the risk is not merely error but the erosion of trust in communicative authority itself. The fear echoes ancient concerns that writing allowed knowledge to circulate independently of those capable of interpreting it responsibly, severing texts from judgment, context, and consequence.

Yet this framing risks misunderstanding both scribal culture and contemporary AI. Mesopotamian writing did not aim to encode inner experience. It aimed to preserve continuity, coordinate action, and stabilize meaning across time. Generative models likewise operate as infrastructural systems that reorganize access to language and pattern recognition. Their danger lies not in imitation but in the temptation to treat output as authority rather than material for evaluation.

Historical perspective clarifies what is at stake. When writing scaled, societies did not abandon interpretation. They professionalized it. Scribes, jurists, priests, and scholars emerged as mediators between fixed texts and lived conditions. Authority shifted upward, concentrating responsibility in those trained to contextualize, critique, and apply inherited knowledge. Generative AI similarly increases the demand for interpretive labor. The more language can be produced effortlessly, the more essential it becomes to evaluate provenance, relevance, and consequence. Mechanical generation does not eliminate the human role. It sharpens it.

Generative AI represents not a rupture but a recurrence. It revives the scribal problem in digital form, confronting modern societies with an old question: how to live with knowledge that can be endlessly reproduced without being fully understood. The Mesopotamian response was not to reject writing but to construct institutions, norms, and hierarchies of responsibility around it. The challenge today is analogous. The task is not to demand originality ex nihilo or to mythologize human creativity, but to insist on accountability, judgment, and contextual awareness in how generative systems are deployed. As before, culture does not disappear when repetition expands. It adapts by redefining where meaning is made and who is answerable for it.

Continuity, Not Collapse: What Mesopotamia Teaches Us

The Mesopotamian experience demonstrates that moments of technological expansion in knowledge production are better understood as periods of reorganization rather than decline. When writing became repetitive and scalable, culture did not unravel into intellectual exhaustion or mechanical emptiness. Instead, societies recalibrated the relationship between memory, authority, and interpretation. The fear that mechanical reproduction would empty knowledge of meaning reflected uncertainty about where wisdom now resided, not evidence that it had vanished. Writing altered the architecture of culture, redistributing where knowledge was stored and how it was accessed, but it did not hollow it out. On the contrary, it made continuity possible on a scale that oral transmission alone could never sustain, allowing ideas, norms, and practices to outlive individual lifespans and local communities.

One of the most enduring lessons of scribal Mesopotamia is that preservation itself can be a creative and stabilizing act. By fixing texts into recognizable and repeatable forms, scribes ensured that legal norms, ritual practices, and intellectual frameworks could survive political collapse, dynastic change, and geographic dispersal. Continuity was not accidental or passive. It was engineered through institutions, training regimes, and shared standards of correctness. Cultural survival depended less on constant innovation than on the ability to transmit meaning intact across generations. What endured was not a frozen tradition but a living archive, one capable of absorbing change without dissolving into incoherence. Preservation, in this sense, functioned as a form of long-term cultural planning rather than mere conservatism.

Mesopotamia also reveals that creativity does not disappear when invention slows. It migrates. As novelty gave way to interpretation, intellectual energy concentrated in commentary, adaptation, and contextual application. Meaning was produced through engagement with inherited forms rather than rejection of them. This mode of creativity was cumulative rather than disruptive, allowing culture to deepen rather than fragment. The scribal system rewarded depth of understanding over expressive individuality, reinforcing the idea that innovation need not announce itself as rupture in order to be transformative.

Equally important is the lesson that authority must be cultivated alongside preservation if repetition is to remain meaningful rather than coercive. Texts alone did not govern Mesopotamian society. Trained interpreters did. Scribes mediated between written norms and lived realities, ensuring that fixed language could be applied with sensitivity to context, circumstance, and consequence. Authority remained human, even as knowledge became increasingly externalized. This balance prevented archives from becoming tyrannical and repetition from degenerating into blind obedience. Cultural continuity required judgment as much as memory, interpretation as much as transmission, and responsibility as much as fidelity to form.

These dynamics challenge the assumption that mechanical knowledge leads inevitably to cultural exhaustion or decline. Mesopotamia suggests the opposite. Systems of repetition can sustain complexity, memory, and meaning over extraordinary spans of time when paired with institutions of interpretation and responsibility. The lesson is not that change is harmless, but that collapse is not its natural outcome. Culture survives by redistributing creative labor, redefining authority, and adapting its understanding of what it means to know. Continuity, not collapse, is the historical norm.

Conclusion: Repetition as a Condition of Civilization

The history of Mesopotamian scribal culture reveals that repetition is not the enemy of civilization but one of its enabling conditions. Writing became powerful not because it preserved novelty, but because it stabilized meaning across time, space, and political uncertainty. What appeared as a loss of mystery was, in reality, a transformation in how culture sustained itself.

This perspective complicates modern assumptions about originality as the primary measure of intellectual value. In Mesopotamia, creativity did not depend on invention ex nihilo but on disciplined engagement with inherited forms. Scribes demonstrated that interpretation, contextual judgment, and recombination could generate intellectual vitality without breaking continuity. Repetition did not flatten meaning. It created a stable field within which meaning could be refined, contested, and extended. The endurance of Mesopotamian culture across millennia stands as evidence that such systems do not stagnate by default. They mature by accumulating depth rather than novelty.

Seen across the long arc of history, the anxieties provoked by mechanical knowledge appear less as warnings of collapse than as signals of transition. Each expansion of knowledge infrastructure forces societies to renegotiate where authority lies, who is qualified to interpret inherited materials, and how responsibility is assigned. From clay tablets to print to digital systems, the fear remains strikingly consistent. Yet civilization persists, reshaped rather than undone by these moments. What changes is not the need for judgment, but its visibility. As repetition expands, judgment must become more explicit, more accountable, and more consciously cultivated, rather than assumed to reside naturally in scarcity or tradition.

The lesson of Mesopotamia, then, is not reassurance but orientation. Mechanical reproduction does not absolve humans of responsibility for meaning. It intensifies it. Culture survives when repetition is paired with institutions, ethical norms, and practices capable of interpreting what has been preserved. Civilization is not sustained by endless novelty, nor by blind fidelity to the past, but by the ongoing labor of making inherited knowledge matter under new conditions. Repetition, far from threatening civilization, is one of the mechanisms through which civilization endures, adapts, and remembers itself.

Bibliography

- Assmann, Jan. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610–623. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2021.

- Charpin, Dominique. Writing, Law, and Kingship in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Daniels, Peter J. “The Decipherment of Ancient Near Easter Scripts.” In Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, edited by Jack M. Sasson, 81-94. New York: Scribner, 1995.

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Floridi, Luciano. The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence: Principles, Challenges, and Opportunities. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Foster, Benjamin R. Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature. 3rd ed. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2005.

- Gitelman, Lisa. Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

- Goody, Jack. The Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Hallo, William W. Origins: The Ancient Near Eastern Background of Some Modern Western Institutions. Leiden: Brill, 1996.

- Havelock, Eric A. Preface to Plato. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Recorded History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1956.

- —-. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963.

- Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

- Latour, Bruno. Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Lucas, Christopher J. “The Scribal Tablet-House in Ancient Mesopotamia.” History of Education Quarterly 19:3 (1979): 305-332.

- Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen R. “Systems for Learning Mathematics in Mesopotamian Scribal Schools.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 54:4 (1995): 241-260.

- Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy. London: Methuen, 1982.

- Oppenheim, A. Leo. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1964.

- —-. Letters from Mesopotamia: Official, Business, and Private Letters on Clay Tablets from Two Millennia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967.

- Postman, Neil. Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology. New York: Knopf, 1992.

- Roth, Martha T. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. 2nd ed. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997.

- Taylor, Jonathan. “Tablets as Artefacts, Scribes as Artisans.” In The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, edited by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson, 5-31. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Van de Mieroop, Marc. Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History. London: Routledge, 1999.

- —-. A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015.

- Veldhuis, Niek. Elementary Education at Nippur: The Lists of Trees and Wooden Objects. Groningen: Styx Publications, 1997.

- —-. “Levels of Literacy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, edited by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson, 68-89. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Wainer, Zachary. “New Approaches to Commentary Formation in Ancient Mesopotamia.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 140:1 (2020): 143-163.

- Williams, Ronald J. “Scribal Training in Ancient Egypt.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 92:2 (1972): 214-221.

- Winter, Irene J. “Royal Rhetoric and the Development of Historical Narrative in Neo-Assyrian Reliefs.” Studies in Visual Communication 7, no. 2 (1981): 2–38.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.27.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.