Exploring a tension between competing historical narratives.

By Dr. Stefan Berger

Professor of History

Director, Institute for Social Movements

Ruhr-Universität Bochum

Introduction

In the debates surrounding the referendum on the British exit from the European Union (EU), the Brexiteers routinely referred to history. A sense of British history as being different and far removed from Continental European history was an important sub-theme of the debate. In particular, nostalgia for Empire and a vague longing for the imagined community of the Second World War played a key role.1 Britain’s long-term internationalist free-trade orientation was also a bulwark against those Remain campaigners who were warning of the dangers of Britain leaving the European free-trade zone. Furthermore, the British self-image as the motherland of liberal democracy and parliamentary government was also frequently underlined by Brexiteers. These historical undertones reflect a long-standing concern in right-of-centre historical accounts that have pondered the role of (largely) English (as opposed to British) history in a wider European narrative. David Starkey, one of the most powerful television historians in the UK, in his Medlicott Lecture given to the Historical Association in 2001, wrote, ‘Maybe we have a future as a series of disparate regions of the European Union, perhaps as a greater city state, in other words, a greater London. But where a history – where an English history, fits in … a sense of England as a place that once existed, that once mattered, that was once glorious – I’m really not sure’ (Starkey 2001).

This sense of tension between commitment to a particular national historical master narrative and challenges by supranational institutions and their historical narratives can also be found elsewhere in Europe. This very tension reflects a deep-rooted concern in European national histories that sought to legitimate nation states vis-à-vis a unique or special national path of development, a path that provided authenticity to national narratives and shaped alleged national characters. Supranational institutions, such as the EU, can easily be perceived as a threat to these cherished national narratives, as indeed we can observe in many European states today. This chapter will trace the development of these particularisms from the late eighteenth century to the present day. In doing so, it highlights the idiosyncrasies between the appeal to the particular and the narrative structuring of those particularist histories according to oft-repeated patterns across diverse European national histories. Arguably, the power of those histories over national imaginations today has waned. Nevertheless, it remains a powerful threat to the EU and begs the question how historians today should deal with national historical master narratives.

Romantic National History Writing and Authenticity

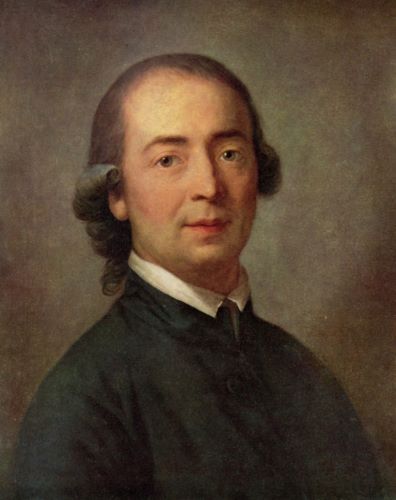

The Romantic tradition of writing history starts in the late eighteenth century with Johann Gottfried Herder’s reaction against the Enlightenment. Himself very much a child of the Enlightenment and unthinkable without it, he had grown suspicious of certain elements within it, including its penchant for universalisms and for a belief in progress. In historical writing this had led representatives of the Enlightenment to trace the progress of mankind throughout the ages, leading to forms of universal history writing in which the authors attempted to follow the most advanced civilizations of their time, whom, they believed, were the carriers of progress. This made for histories that ranged widely, in terms of space and thematically; it also made for histories that privileged the successful and the powerful over the marginal and the powerless. Herder’s cosmopolitanism was one that took offence at this idea and instead sought to put all civilizations on an equal par. He did this by arguing that people were naturally organized into nations and that these nations possessed distinct characteristics from other nations that endowed them with their own worth and value. As Herder abandoned the idea of universal values, one was not necessarily better or worse than the other. In typically Herderian organicist language, world civilization was presented as a tree from which various branches grew that were quite different in shape, strength and outlook; yet each branch claimed its own value and worth in itself and helped to make up the entirety of the tree.2

Unsurprisingly, this revolutionary idea was picked up with a vengeance, especially by those peoples who had been marginal and weak in the universal histories of the Enlightenment. Throughout nineteenth-century Europe we find a proliferation of Herders in many places whose writings all aimed at establishing what characterized their own nations. Therefore national history not only became the centre of attention; it also was, indeed above all, concerned with authenticity and uniqueness. Whereas Enlightenment historians could and did write national history as well, their concern was with tracing how the nation advanced the whole of mankind, how it was marching at the helm of progress. Now, in Romantic historical writing, this was turned on its head. The success of this exercise was not merely rooted in intellectual fashions, but happened against the concrete backdrop of the experience of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic attempt to conquer Europe. Apologists for both the French Revolution and Napoleon argued within a strongly universalist framework. National history was an important means of rejecting these universalisms along with French armies and for preparing an intellectual defence against occupation.3

Thus, for example, Fichte specifically called for a national history of the Germans as the best defence against French universalism: ‘Amongst the means of strengthening the German spirit, a powerful one would be an enthusiastic history of the Germans, which would be a national as well as a people’s book, just like the Bible or the Song Book’ (Fichte 2008 [1808]: 106). Fichte’s idea of history as a bulwark against the French Revolution found its parallels elsewhere, for example, in the thought of Joseph de Maistre in France and of Edmund Burke in Britain. For all of them, the study of national history allowed access to a vision of a nation fundamentally at odds with that created in the French Revolution. With their emphasis on the continuity of national historical evolution, Friedrich Schlegel’s 1811 Vienna lectures on modern history summarized some of the key characteristics of Romantic historiography. Invariably, each state and nation had its own individuality and each Volk its own unique authenticity. The totality of Christian Europe was made up of such national individualities. Overall, authenticity, longevity, unity and homogeneity became the hallmarks of Romantic national history-writing. ‘Growth’ and ‘evolution’ were its key metaphors, stressing the durability of national characteristics and the permanence of the Volk. Tradition, as represented by history, was juxtaposed with sovereignty as formulated by the French revolutionaries.

Ironically, the search for national features produced, in European national historiography, a patterning applicable to many national histories. While the narratives that were produced aimed for distinctiveness, they in fact resulted in narrative tropes and structures that can often be traced back to pre-modern forms of national history writing. These same narratives established an enduring legacy for national historiographical traditions well into the second half of the twentieth century and beyond. Thus, to give a few examples, many Romantic national histories became obsessed with defining the territory of the nation. The German cultural historian Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl argued that the national characters of all peoples were rooted in the soil and landscape they inhabited. He juxtaposed the wild, warlike and freedom-loving peoples of the forest with the tame, civilized and peaceful peoples of the field (Riehl 1897; also Riehl 1990). In the larger nations of Europe, territorial definitions of the nation incorporated the idea of the nation being made up of diverse regions. Michelet was all too aware of the wealth of regional and local historical studies and the diverse possibilities of conceptualizing national history, when he started the second volume of his History of France, published in 1833, with a ‘tableau de la France’, in which he surveyed the different regions of his country, describing their diversity but ultimately reassuring his readers that the regional differences came together in a homogeneous whole called ‘France’ (Thiesse 1999; Brakensiek and Flügel 2000).

Apart from an obsession with defining national territory, many national histories were either strongly oriented towards the state, mainly if they could look back on a long history of independent statehood, or referred back to the people as the backbone of the nation, mainly in areas where statehood had not existed at all or had been interrupted for a long time. Overall, state and people became the central axis around which national histories were organized. Furthermore, in their search for authenticity, virtually all national histories traced their histories as far back as possible until their stories were lost in the mists of time. The Middle Ages was a period when, with the exception of Italy and Greece, which harked back to ancient times, national history fully came into its own. The periodization of national histories often followed rise-and-fall narratives that ended either on the actual or on the predicted rise of the nation, whether in the present or the future. Canons of national heroes and enemies were constructed. Many national histories followed similar ideas. One popular notion, for example, was nationhood as the continuous extension of the idea of liberty. Invariably, across Europe, the idea of the nation had to position itself vis-à-vis a range of other, potentially rival master narratives, including those of class, ethnicity/race and religion. Indeed, a remarkable feature of Romantic national history writing across Europe consists of the extent to which the Romantic historians managed to incorporate those potential rivals into their national storylines, so that ethnic, religious and class characteristics became alleged hallmarks of national attributes.4

Legal historians, influenced by Romanticism, could play a crucial role in establishing national characteristics through distinct legal traditions. Carl Friedrich von Savigny, for example, was extremely important in arguing against rationalistic French jurisprudence. He was convinced that law developed historically according to national cultural logics which differed in disparate parts of Europe. Savigny’s ideas paralleled those of Ranke, who also believed in diverse national trajectories rooted in historically specific primordial national types, for example, Celts, Germans and Latin and Slavic peoples.

The age of Romantic historiography also saw a range of historians forging legal documents in an attempt to invent legal traditions that were to prove specific national characteristics. Vaclav Hanka, for example, forged Czech legal documents in 1818 to prove the independent development (from the German one) of an ancient Czech legal tradition (Otáhal 1986). In early nineteenth-century Catholic Irish historiography, legal history was instrumental in preparing the road for the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 by arguing consistently against the body of Protestant Irish historiography that the 1691 Treaty of Limerick provided a contract guaranteeing legal rights (McCartney 1957).

Scientificity, Nationalism, and the Need for ‘Being Special’

Across Europe, the Romantic historiographical tradition was heavily criticized by subsequent generations of more professionalized historians. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the institutionalization of historical writing at universities and academies gathered pace, as states and governments came to perceive the usefulness of history for purposes of state integration and stabilization, especially in an age of mass politics. If we take the example of Romania, after the foundation of the Romanian state in 1862, the state administration quickly united the archives in Wallachia (founded in 1831) and Moldavia (founded in 1832) and vigorously promoted research into national history. The state expanded the University of Iaşi (1860) and founded the University of Bucureşti (1864), the Muzeul Naţional de Antichităţi (National Museum of Antiquities, 1864) and the Societatea Academicǎ Românǎ (Romanian Academy, 1867) and gave national history a prominent place everywhere. The Academy was to play a hugely influential role in publishing key sources of Romanian national history through the Hurmuzaki collection, published in forty-five volumes between 1876 and 1942. It also organized yearly prizes for the best publications in national history and through its own yearbook participated actively in constructing a specific national master narrative that was to differentiate it clearly from its neighbours. The Comisia Istoricǎa României (Historical Commission of Romania) was founded in 1910 by the Ministry of Education with the specific task of publishing more historical sources, especially critical editions of medieval manuscripts (Murgescu 2010: 100).

The training of historians became more formalized and the disciplinary methodological and theoretical arsenal of the historian became more refined. As a result, professionalized historians could claim that they were the only ones, qua trained specialists, who could speak authoritatively about the past and that therefore they were privileged in comparison to other disciplines and genres also dealing with the past. In an age of historicism, during the second half of the nineteenth century, they were remarkably successful in pushing through this idea. Yet their exclusive claims to scientificity did not see a significant break with historiographical nationalism across Europe. Quite the contrary, historians continued the Romantic tradition of acting as prophets and seers of the nation, devising strategies of ever greater authenticity and narrow specificity, only now with renewed scientific claims and enhanced authority (Feldner 2010).

Their strong orientation towards the nation and increasingly the nation state meant that historiographical nationalism even increased in the second half of the nineteenth century and up until the outbreak of the First World War. In Scotland, the development of a more self-consciously ‘scientific’ historical science went hand in hand with patriotic and civic education emphasizing the distinguishing features of Scotland (Anderson 2010). In Finland, the University of Helsinki, founded in 1825, became a hotbed of Fennoman nationalist history writing from the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, with two historians in particular, Georg Zacharias Forsman and Zacharias Topelius, constructing the canon of Finnish national history that was also characterized by its specific features (Haapala and Kaarninen 2010: 75).

Empires and multinational states alike often reacted to the challenges of national movements at their peripheries by promoting historical national master narratives foregrounding a central national storyline into which peripheral nations could be incorporated. Historians have for too long seen empires and multinational states only as ‘victims’ or ‘oppressors’ of national movements, ignoring the fact that these polities developed nationalizing strategies with the intention of keeping the empire together by establishing a unique and highly focused narrative about its national core and its peripheries (Berger and Miller 2015).

Professional historians, whether writing on empires or nations, stuck to the Romantics’ obsession with specific national features. Yet at the same time national histories across Europe also continued their pattern of mutual resemblance. In other words, national history aimed at being unique but often produced more of the same. So, for example, the specifics of Polish, Romanian, Russian, Swedish, British, Spanish and other national histories in Europe resulted from an allegedly close and even unique affinity with religion, whether Catholicism, Orthodoxy or Protestantism. Yet the alleged special affinity of one nation with one religion was consistently reproduced elsewhere in Europe (Hermann and Metzger 2015). The same could be said for the racialization of national historical consciousness from the last third of the nineteenth century onwards. Many national historians sought to prove scientifically, by reference to history, the superiority of the specific racial characteristics of their own nation over others. The arguments were framed with a view to specificity and exclusiveness but they again followed a common patterning. To illustrate – if we take Hungarian national narratives – the Hungarian national master narrative was also bound up with notions of Hungarians as descending from ‘tribes from the East’. If Hungarian historians of the early nineteenth century routinely depicted Hungary as a multi-ethnic nation state, the search for the ‘Asian roots’ of the Magyar nation was a direct attempt to homogenize the ethnic origins of the Hungarian nation and, at the same time, assimilate non-Magyar ‘tribes’ along often racialized and social-Darwinist lines (Zsolt 2010. See also von Klimó 2003: chapter 4).

The uniqueness of national paths could also be borrowed. If we take the example of German national history, German historians working on ancient Greek history did not tire of emphasizing how intimately related the German national character was to that of the ancient Greeks. Wilhelm von Humboldt, who formulated this idea at the beginning of the nineteenth century, could already draw on arguments put forward in the mid-eighteenth century by Johann Joachim Winckelmann and in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, both of whom stressed the spiritual, cultural and educational proximities between ancient Greeks and contemporary Germans. Humboldt, following Goethe, still perceived the plurality of the German nation state as a direct parallel to the plurality of the ancient Greek city states. Ancient Rome had built an empire and might therefore be best compared with contemporary imperial nations such as Britain or France, but ancient Greece was characterized not by nation or empire building but by attempts to perfect human education: what the Germans came to refer to as Bildung. Nevertheless, ancient Greece also became a political model for contemporary Germany – a federal system united by culture. Analogies with the contemporary German Kulturnation were all too obvious. Moreover, later on, Droysen’s writings on Alexander the Great were not shy in pointing out the parallels between Macedonia and Prussia. If it had been Macedonia’s telos to unite all the Greek city states into one powerful nation state, so it was Prussia’s telos to unite all the German tribes into one powerful German nation state which could defeat its enemies and secure Germany’s ‘rightful place’ among the great nations of Europe (Funke 1998).

National uniqueness was rarely uncontested. Looking at Russia, in Russian national history, for example, we encounter one of the biggest and longest-running historical debates focused on this very question of Russia’s peculiar position vis-à-vis Europe and the West. Historians such as Samarin argued that Westernizing influences in Russia’s history had weakened the nation by subverting the spiritual and political foundations of the country, that is, Orthodoxy, the village community and Tsarism. His writings were full of vigorous attacks on what he perceived as lifeless cosmopolitanism. By contrast, his colleagues Solov’ёv and Boris Nikolaevič Čičerin emphasized that it would be impossible to maintain Russian traditions if the aim was to modernize the nation. Only the Western path promised a modernity that would, at long last, free Russia from its inferior and backward position vis-à-vis Europe. Not all Russian historians fit neatly into these two camps. A variety of intermediate positions could also be found. So, for example, Michail Petrovič Pogodin divided European history into a Western and an Eastern European path. They corresponded to a distinction between Rome and Constantinople. Russia, Pogodin argued, was the heir of the Eastern tradition. Hence Pogodin positioned his country to some extent in opposition to the West, but at the same time he was also full of praise for Peter the Great, who had allegedly brought Russia into the mainstream of European civilization. The uniqueness of Russia, according to Pogodin, lay precisely in its ability to reconcile Western and Eastern traditions.5

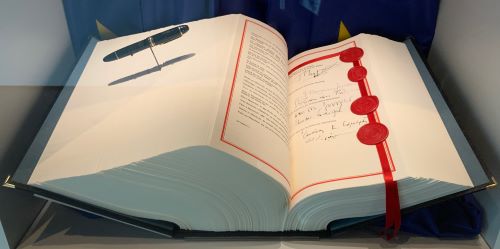

The prominence of legal history in the framing of national uniqueness continued with the growing professionalization of the historical sciences. Thus, for example, constitutional history in Britain was hugely important in framing the national master narrative. Stubbs’s Constitutional History of England, published between 1874 and 1878 in three volumes, famously described thirteenth-century England as a location where the English people had united around the constitution and had formed a consensus unperturbed by divisions of class, race or language. Ever since, according to Stubbs, English history has amounted to one long struggle to maintain, defend and develop those constitutional rights (Mitchell 2000). Yet the importance of constitutional rights and legal traditions was also highlighted in many other national histories across Europe. In the nineteenth century, where national historical narratives were underpinned by massive source collections, many of those collections explicitly assembled legal documents related to the formation and development of the nation state. In England, the Whig story of ancient English liberties and constitutional progress simply had to be extended to incorporate the Scots and the Welsh and potentially, as in Seeley’s national history, all white-settler communities in the Empire – a Greater Britain indeed. A narrative of a unique civilization and its civilizing mission underlay this revamped national history, which was to safeguard the multinational state against threats from nascent national movements and their historical master narratives in Ireland, Scotland and Wales (Mycock and Loskoutova 2015).

The High Point of Historiographical Nationalism betwen the Wars

Historiographical nationalism, based on assumptions of unique authenticity, reached a high point at the time of the First World War. Stories of national features and characteristics in aggressive juxtaposition to those of the enemy were vital for a wide variety of intellectual justifications of diverse war efforts. In 1915 Friedrich Meinecke (1862–1954) published a collection of his speeches and articles that justified the German war effort by reference to German history, which he interpreted as a long search for national independence against foreign enemies. The wars of liberation against Napoleon in 1812–13, the revolution of 1848 and the wars against Denmark (1864), Austria (1866) and France (1870–1) were all stepping stones to realizing the sovereign German nation state representing a unique spiritual heritage that was superior to all other national essences. Meinecke saw the specific German national character rooted in a combination of inner freedom (Innerlichkeit) and the ability to sacrifice selfish desires for the good of the community. In contrast to the historically developed higher German form of humanity stood the humanity of the ‘West’ which Meinecke identified with uniformity, egotism and degeneracy (Meinecke 1915. See also Stibbe 2003). Historians from the Allied nations replied in kind, constructing various historical missions delineated from their own specific national pasts (Wallace 1988; Krumeich 1996).

In the major struggles of the interwar period between democracy and the totalitarianisms of the twentieth century, a range of discursive constructions of national particularities were prominently present. In the struggle of the Italian anti-fascists, the idea took root that fascism emerged as a direct consequence of an allegedly unique national trajectory. The brothers Rosselli, for example, argued that the Risorgimento had been unfinished, and claims by the fascist regime to be its heir had to be contested historically. An alternative, republican and socialist Risorgimento had to be upheld against the rival claims of the fascist state. The Rossellis were influential in defining the anti-fascist struggle as a ‘second Risorgimento’, a trope that became popular in Resistance circles during the Second World War. It sought to expound the unity of the Italian nation on the basis of social justice and emancipation (Morgan 1999).

In Spain, the re-Catholicization of Spanish national historical consciousness under Franco saw new attempts to write national history in a uniquely Catholic key. This in turn found expression in the idealization of medieval Christendom, stress on the moral purity of Spanish Catholic nationality and the strong role of Opus Dei in history departments and historical education more generally. The nation became synonymous with the church and the monarchy (Boyd 1997: chapter 6). In Germany, the historian of the Catholic Centre Party, Carl Bachem (1858–1945) also described political Catholicism as an expression of the German national character, thereby confirming once again that similar patterns were the norm rather than the exception in framing national peculiarities in national historical master narratives in Europe (Kiefer 1989: 197ff ).

In Britain, one of the bulwarks of interwar liberal democracy, liberal historians such as George Macaulay Trevelyan used their positions of public influence to stress the organic link between a special historical past and a contemporary political mission. In a speech written for George V and delivered on the occasion of the opening of Parliament in 1935, Trevelyan wrote,

It is to me a source of pride and thankfulness that the perfect harmony of our parliamentary system with our constitutional monarchy has survived the shocks that have in recent years destroyed other empires and other liberties …. The complex forms and balanced spirit of our Constitution were not the discovery of a single era, still less of a single party or of a single person. They are the slow accretion of centuries, the outcome of patience, tradition and experience constantly finding outlets … for the impulse toward liberty, justice and social improvement inherent in our people down the ages. (Cited in Hernon 1976: 86)

These sentences were a patriotic assertion of the Whig view of historiography that had associated constitutional liberties and democratic traditions with Englishness throughout the nineteenth century. This decidedly Whiggish view of British national history remained strong in popular historical writing in interwar Britain, not just among liberals.

Newly founded states in the interwar period were particularly prone to harnessing the power of uniqueness to justify their new-found statehood. Thus, historians close to the Kemalist revolution at the heart of modern Turkey stressed that Turkish was the original language of mankind and glorified Turkishness as the cradle of humanity. This view declared Turks to be Aryans and identified contemporary Turks with the ancient Hittites, thereby moving the foundation story of Turkey back by several centuries (Kieser 2005).

In Latvia, historians established an official national master narrative, in particular refuting the claims of Baltic German historiography over their territory. Focusing on agrarian history, their work sought to demonstrate that the claims of Baltic Germans to the land were spurious and that redistribution of land to Latvian smallholders was historically justified. The special status of a nation of small-holding peasants oppressed by a foreign occupier was, of course, an oft-repeated story in Europe, not just in the Baltic States. According to the argument of nationalist Latvian historians of the interwar period, the distinctive features of prehistoric pagan society of the Ur-Latvians, who were allegedly committed to social egalitarianism under wise leadership until the Crusaders put an end to it and established colonial rule over Latvia in the thirteenth century, could only be rediscovered after seven centuries of darkness with the formation of an independent Latvia at the end of the First World War (Šnē 2010: 82).

Notions of uniqueness could go hand in hand with justifying an internationalist and cosmopolitan mission. In interwar Switzerland, nationalist appropriation of the medieval past of the Old Confederacy reached its high point in and around the Second World War, when homeland defence against Nazi Germany became a key issue. This appropriation was depicted in terms of defence of ancient Swiss neutrality and freedoms. But by the 1920s many Swiss histories combined notions of the Alps as protector of the sources of major European rivers with ideas of Switzerland as the home of the new League of Nations. The specific feature of neutrality and ancient freedoms mixed with geographical location was used to lay claim to be a champion of internationalism (Marchal 2006).

To take another example, Belgium, as a crossroads of cultures, so Henri Pirenne argued after the First World War, was specially predestined to lead the way in an international examination of the methodological ground rules of historical writing (Harvey 2003: chapter 6). However, at the same time as Pirenne was promoting his native country as a unique cosmopolitan microcosm, he was faced with the rise of an ethnically rooted Flemish nationalism. Flemish historians regarded Belgian history à la Pirenne as an invention of early nineteenth century French diplomats and provided their own Flemish master narrative. The specific features of the region-cum-nation challenged the universalism derived from a specific construction of a Belgian national master narrative (Beyen 2007: 44f ).

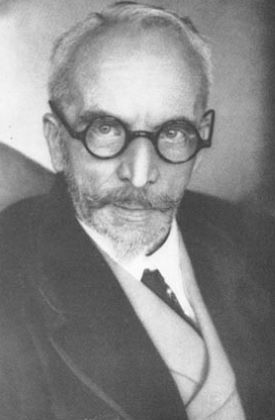

In the young Soviet Union, notions of Soviet distinctiveness vis-à-vis the West figured prominently in debates surrounding the revolutionary strategy to be pursued by the first Communist state. Those who followed a well-established trope in socialist historical discourse about the backwardness of Russia due to its specific historical trajectory argued that communism would not be able to survive in Russia unless the Russian Revolution was followed by revolutions in the more developed West. As this became increasingly illusory in the course of the 1920s, Stalin’s idea of ‘socialism in one country’ was equally based on notions of the uniqueness of Russian history that predestined it to build communism unsupported by successful revolutions in the West. Russian Marxist historiography was best represented by Georgij Plechanov, whose Istorija russkoj obščestvennoj mysli (History of Russian Social Thought), published in 1909, paid much attention to Russian national history, which he described as deviating in major ways from the history of West European nation states. Russian national history was closer to certain oriental and Asiatic societies than West European ones, which explained much of Russia’s backwardness. According to Plechanov, despotism and immobility became the hallmarks of Russian national development. Whereas in the West the Marxist idea of different stages of economic production succeeding each other until capitalism was reached was valid, in Russia primitive communism was followed directly by oriental despotism. In other words, Russia was not yet a developed capitalist country, which also made it the most unlikely location for a successful working-class revolution (Baron 1963). Michail Pokrovskij, who became the undisputed leader of Soviet Marxist historiography in the 1920s, nicknamed ‘Supreme Commander of the Army of Red Historians’, begged to differ. His Russkaja Istorija v samom sžatom očerke (Brief History of Russia) was approved by no less a figure than Lenin and served as a bible for the first generation of Marxist–Leninist historians in the Soviet Union. As a national history it indeed sought to establish a new national master narrative portraying the history of Tsarist Russia as a ‘dark other’, where not only the working classes but also the non-Russian nationalities were repressed. He contrasted the Russian past sharply with the bright Communist future of the Soviet Union under Bolshevism. In line with Marxist thinking, he depicted the history of Russia as a history of class struggle. However, contrary to Plechanov and Trotsky, Pokrovskij described Russian historical development as essentially following the same trajectory as that of Western Europe. By assimilating Russian history into the West European model, Pokrovskij gave historical explanation, justification and, not least, hope to the Russian Revolution of 1917 (Enteen 1978).

In the interwar period, legal history continued to play an important role in underpinning notions of uniqueness and specificity. In Hungary, for example, historians justified their country’s post-war territorial ambitions via the ‘Idea of the Holy Crown of St Stephen’, a nineteenth century legal concept about the integrity of the lands of the Hungarian crown within the Habsburg monarchy. The Horthy regime generously supported the annual Saint Stephen’s procession after 1920. The admiral himself marched ahead of the procession (despite being a Calvinist) every 20 August, and the military participated prominently in the festivities leading to militarization of the religious cult in the interwar period. On the occasion of the 900th anniversary of the death of Saint Stephen in 1938, the Catholic Eucharist Congress was held in Budapest and around 800,000 people participated in the procession. The mayor of Budapest, Ferenc Ripka, even commissioned a historical study in 1927 which was to prove once and for all that the annual Saint Stephen’s procession was not an invented tradition as was claimed by Protestants and socialists (von Klimó 1999a; von Klimó 1999b).

Appeals to law, in this case international law, were also important in the context of justifying British involvement in the First World War. The University of Oxford’s Faculty of Modern History published a pamphlet immediately after the outbreak of hostilities in which they argued that Britain was upholding the international rule of law against the authoritarian and militarist étatisme of Germany (Why We Are at War: Great Britain’s Case (1914)).

The Restition of Traditional and National Historical Narratives after the Second World War

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, national histories found themselves deeply destabilized through the histories of fascism, war, occupation and collaboration in most parts of Europe. It is striking to what extent references to uniqueness and specificity were used to stabilize traditional national narratives in the post-war period. Sometimes these were new constructions. In the case of Austria, for example, the theory of Austria having been the ‘first victim’ of Hitler’s aggression served the purpose of avoiding questions of perpetratorship and historical guilt. The National Socialist period of Austrian history could be externalized and made into something foreign. Austrian historians played a major part in shaping an independent and separate Austrian national consciousness that had been so manifestly absent in the interwar period. A ‘coalition historiography’ of Catholic and socialist historians stressed the common anti-fascism of the Austrian people and ignored the many incidents of voluntary collaboration with Germany (Utgaard 2003). The idea of a separate Austria, built on notions of ‘special development’ within the Babenbergian–Habsburg countries during the Middle Ages, highlighted the baroque period and enlightened Josephinism as ‘formative phases’ of Austrian national history. The Habsburg monarchy was now interpreted as a positive antidote to the aggressive nationalism of the German Empire and as a model for the bridging function that the independent and neutral Austria allegedly fulfilled in the Cold War – mediating between East and West (Marjanović 1998).

In a similar way, German post-war historical narratives externalized the question of guilt and responsibility by arguing that National Socialism was not rooted in positive and unique German national traditions, but in modern mass society, associated with the French Revolution and its aftermath, and in Italian fascism. For historians, such as Gerhard Ritter, Hans Rothfels and Herman Aubin, the good national tradition was represented by the national conservative opposition to Hitler, that is, those who had plotted to assassinate Hitler on 20 July 1944 (Cornelißen and Ritter 2001; Eckel 2005; Mühle 2005). Furthermore, memories of wartime bombing, of the suffering of ordinary soldiers and of ethnic cleansing were cultivated in order to allow a positive national historical consciousness to re-emerge after 1945 (Berger 2006).

In Italy we can observe a similar attempt to decouple a favourable national trajectory from the history of Italian fascism. The former was represented by the nineteenth-century Risorgimento (Levy 1999). Historians from the centre-left, such as Gaetano Salvemini, who had been exiled during the fascist years, and centre-right historians, such as Federico Chabod, united forces to preserve a good deal of the traditional national master narrative. As in Germany, the Resistance was key in allowing historians to locate favourable national traditions outside of fascism. The Resistance was routinely portrayed as a second Risorgimento. By concentrating on the period of German occupation after 1943, Italian historians could furthermore present a picture of a genuinely popular anti-fascism struggling against foreign occupiers and a small clique of Italian collaborators.6

In Communist Eastern Europe after 1945 most national histories, resting on understandings of uniqueness and specificity, were simply painted red. In other words, a Marxist–Leninist class interpretation of history was placed over the well-established national narrative, retaining most elements of the latter. In the GDR, for example, national histories still routinely referred to the wars of 1813–14 as national ‘wars of liberation’, the national movement of the first half of the nineteenth century was viewed as uniformly progressive, the war against France in 1870–1 was frequently portrayed as a defensive war, and the Bismarckian solution to the German question was presented as having lacked alternatives. All of these interpretations were harking back to traditional forms of Prussianism in national historical writing (despite the formal dissolution of Prussia in 1947), and were relatively unaffected by Communist reinterpretations (Iggers 1989: 69). An exception is the Romanian historical master narrative that emerged in the post–Second World War years. A marked negativity towards Romanian national history coincided with an emphasis on building Romanian communism entirely on the glorious Soviet example. The most important representative of this negative inversion of national history was Mihail Roller (Murgescu 2010: 100). This phase of national self-deprecation, however, lasted only until 1958 and was followed by a period of hypernationalism. Increasingly, historians merged the dictates of Marxism–Leninism with traditional nationalist narratives (Durandin 2002; Kellogg 1990).

In Britain, the traditionally forceful Whig narrative of British national history as an expansion of liberty and freedom survived in British historical thinking throughout much of the twentieth century (Bentley 2005), and now began to incorporate the national story of the emancipation of the working classes – nowhere more emphatically than in the work of the Communist Party Historians’ Group, among which could be found some of the most influential Western Marxist historians, such as Eric Hobsbawm and Edward Palmer Thompson (Kaye 1984; Schwartz 1982; Elliott 2010).

Several of the countries that remained neutral in the conflict of the Second World War also appealed to the specific features and characteristics of their respective national histories. In Switzerland, for example, a strong self-image was the idea of a charitable Switzerland, home of the Red Cross, which had granted asylum to the ‘victims’ of National Socialist Germany. Switzerland as a nation had a long tradition of neutrality and its national narrative of the Second World War therefore fitted neatly with its construction of national tradition and identity (Zala 2003). Sweden’s historians similarly emphasized the country’s position as a peaceful oasis on the margins of Europe, conveniently forgetting Sweden’s past as an early modern great power. Rather than participating in the horrors of the Second World War, Sweden, they argued, did the right thing in concentrating on the country’s build-up of its model welfare state. The home front was lovingly depicted as strengthening solidarity under the ideal of the ‘people’s home’. The only aspect of war that was depicted positively was the willingness of Swedish volunteers to fight alongside the Finns in the Winter War – against Sweden’s old enemy, the Russians (Liljefors and Zander 2004).

Challenging Uniqueness amidst a Crisis of National Historiography

A significant break with particularist narratives underpinning positive constructions of national master narratives was only attempted in the course of the 1960s – in the context of profound institutional and political change. In Eastern Europe the diverse reform communisms of the 1950s and 1960s sought to challenge not only the Stalinist legacy of communism but also the red nationalism underpinning many national histories in East Central and Eastern Europe. In Western Europe, the political challenges loosely associated with 1968 combined with a massive expansion of the system of higher education to provide the conditions for a successful challenge to established historical master narratives based on notions of specificity and uniqueness.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, the Fischer controversy, a debate surrounding Fritz Fischer’s claims about the Imperial German elite’s responsibility for the start of the First World War, started a process in which a younger generation of social historians inverted the old Sonderweg theory and began to examine the long-term, nineteenth-century roots of the success of National Socialism (Moses 1975; Petzold 2011). One set of particularist assumptions was replaced with another, highlighting the continued appeal of exceptionalist arguments in national historical master narratives. In Italy, too, historians began to see continuities between nineteenth-century Risorgimento nationalism and the rise of fascism after the First World War. In both countries, the reception of Anglo-American historical works, which had been far more critical of the German and Italian national traditions, were important in furthering those critical historical writings inside the FRG and Italy. In West Germany, exiled historians, such as Hans Rosenberg, served as transmitters of the more critical Anglo-Saxon interpretations of the German past (Winkler 1989). And in Italy, it was an archetypal Oxbridge don, Dennis Mack Smith, whose history of Italy linked the Risorgimento directly to the rise of fascism, thereby drawing attention to the continuities in Italian national history. It was received well by Italian social historians who had already embarked on the road to more self-critical perspectives on Italian national history.7

Yet, this break with particularisms, often only resulting in the formulation of new particularisms, was again contested in the 1980s when a return to more traditional national historical master narratives could be observed in many parts of Europe. Thus, in France, for example, occurred an outpouring of national histories, of which arguably the most prominent was Fernand Braudel’s ‘L’identité de la France’. Here the undisputed leader of the post-war Annales school, who had strategically abandoned national history with his path-breaking book on the Mediterranean, returned to national history and ultra-traditional national history at that. Naturalizing the borders of France established in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, alluding time and again to the ethnic origins of the nation, revelling in the regional diversities making up the allegedly unique French whole, Braudel argued in favour of the assimilation of immigrants and confirmed the Gaullist myth of the ‘true France’ in exile and opposition to Pétain’s France under occupation (Braudel 1986).

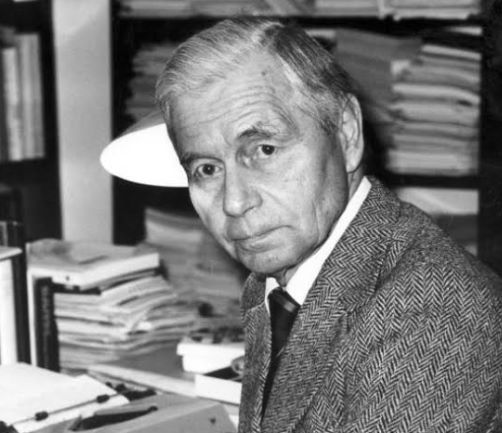

In Italy, as more and more historians came to doubt the simplistic story of heroic Resistance between 1943 and 1945, the archive-based studies of Renzo de Felice (1929–96) put forward a revisionist interpretation of Italian fascism, which distanced it from German National Socialism and emphasized its genuinely revolutionary characteristics and popular appeal. It had been, in other words, a highly specific Italian affair and could not be subsumed under a generic understanding of European fascism.

In the FRG, the Historikerstreit (‘Historians’ Controversy’) erupted in 1985, focused on the singularity of the Holocaust and the need to renationalize German identity. Conservative-liberal historians, such as Michael Stürmer, who acted as a political advisor to Chancellor Helmut Kohl during the 1980s, accentuated the more positive elements of German national history and argued that it was impossible to appreciate the characteristics of German national histories in all their manifold contradictions. According to him, an almost exclusive attention focused on the twelve years of National Socialism in German history had streamlined German history too much in the direction of a negative German special path. By contrast, critical left-liberal historians, led by the philosopher Jürgen Habermas (*1929), argued against any renationalization of German national identity and against the apologetic use of history. Instead they championed ideas of constitutional patriotism and post-nationalism – in themselves concepts that, by and large, set Germany apart from other European nation states in which these concepts were often seen as specific German features.8 An important deviation from the discourse of particularity came about in a reunified Germany, when a broad alliance of right-of-centre and left-of-centre historians began to ‘search for normality’. The best known expression of this was Heinrich August Winkler’s two-volume The Long Way West, which argued that Germans had travelled a tortuous path to bring German national identity into line with ‘normal’ Western national identity. While both the history of Germany before 1945 and the histories of the divided Germany before 1990 represent deviations from Western ‘normality’, reunification in 1990 presented the Germans with a unique opportunity to develop a ‘normal’ national identity built on Western understandings of the nation state.9

Britain did not escape the trend towards renationalization in the 1980s. Right-wing historians in Britain had for some time established a conservative interpretation of Britain’s past, which had been remarkably successful in permeating British national consciousness (Soffer 2009). Margaret Thatcher, who had no great interest in history per se, encouraged the heritage mania of the 1980s, making frequent positive references to Victorian values and Empire. The epic national historian Arthur Bryant (1899–1985) was a staunch supporter of Thatcher. He reached mass audiences with his pleas to save the unique national character from the allegedly all-devouring, all-flattening EU. He depicted the EU as a Brussels monster that was about to extinguish the British national identity. The latter, he argued, had grown organically over the centuries (Stapleton 2006). In line with the political mood of the times, Geoffrey Elton (1921–94), Regius professor of history at Cambridge University, denounced unpatriotic historians and called for a renewed commitment to teaching the glories of English political history.10

Yet, the return to national history was by no means an uncontested development. Everywhere it has been and continues to this day to be vociferously contested by those historians critical of apologetic historical writing that seeks to provide positive forms of national identity. While national history writing is blossoming in many parts of Europe today, we see at the same time a massive growth of global and transnational history. While the criticisms of national apologetic forms of criticism in the 1960s and 1970s often themselves harked back to explanations that fell back on national particularity, the more recent transnational and global approaches have successfully avoided the discourse of particularity, replacing it with a discourse of connectedness that seems precisely to question the validity of talking in terms of peculiarly national characteristics, revealing these to be constructions in the service of nation formation and development.

Conclusion: What Place for National History in Contemporary Europe?

The above analysis has demonstrated to what extent the development of national historical master narratives has depended on constructions of particularisms and special historical trajectories, despite the fact that any closer look at these quickly reveals patterns of national historical narratives that look remarkably similar across a range of different national histories in Europe. This highlights the ways in which such particularisms have been and continue to be used to contribute to nation formation and development. From a critical perspective towards such functional uses of national history, what role is national history to play in the future?

For a start, more recent national histories have started from a critical re-evaluation of national historical master narratives, often telling counter-stories to the traditional ones. Jakob Tanner’s recent history of Switzerland is a good example of such a critical self-reflective national history that very effectively breaks open the national container and contextualizes notions of national uniqueness in a wider transnational framework (Tanner 2015). Several national histories have also been deliberately playful about identity as well as less homogenizing. The critical impetus continues in many places. Irish national history, for example, has witnessed vigorous debates since the 1970s – with Irish historians questioning the extent of Irish suffering, the levels of British oppression and the effectiveness of Irish resistance to the British, all topics of totemic significance for Irish nationalist narratives (Foster 2002).

Other examples of these self-critical and self-reflective forms of national historiography include the French desire to come to terms with the war in Algeria (Stora 1999), the tentative beginnings of problematizing the Francoist past in Spain (Sartorius and Alfaya 1999), the New Historians’ attempts to undermine entrenched Zionist positions in Israeli historiography (Shapira and Penslar 2003) and Swedish research into violations of neutrality during the Second World War (Zetterberg 1992). Even in Eastern Europe, many of the renationalizing historiographies found it difficult to produce homogenous national master narratives. Instead, plurality has emerged out of very different attempts to narrate national history under post-Communist conditions. Amidst all the nationalist history writing of post-Communist Romania, Lucian Boia’s work has attempted to blur the line between fact and fiction in Romanian national history, thereby calling into doubt the very scientificity of national history writing on which its authority and political influence was based. His study on the relationship between myth and Romanian national history shows that the debunking of national myths remains controversial depending on place and context (Boia 2001).

Overall, therefore, there is ground for optimism. The debate between those wanting to use particularisms and special paths in order to legitimate proud constructions of national difference and instil in their readers feelings of national pride and those wanting to point to the constructed nature of national history and national identity reflecting particular political purposes is likely go on, but this is a healthy state of affairs in democratic nation states. Debates on who we are, who we have been and who we want to be in future can only be conducted in relation to a variety of ‘others’ and as long as we can openly debate the content and relationship of that ‘us’ and ‘them’ in a non-violent way, we have a lively polity.

Appendix

Endnotes

- http://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/the-brexit-syllabus-british-history-for-brexiteers/ (accessed 25 January 2017).

- On Herder, see Nisbet 1999; Adler and Menze 1997. See also Berlin 2000; Adler and Köpke 2008. On Enlightenment historical writing compare Reill 1975; Bödeker, Iggers, Knudsen and Reill 1986; Abbatista 2012.

- On Romantic nationalism, see the excellent overview of ‘On the Development of National Thought in Europe’ by Leerssen 2006, especially the pages on Romantic nationalism, and also his Encyclopaedia of Romantic Nationalism project: http://romanticnationalism.net/viewer.p/21 (accessed 25 January 2017).

- For a more extensive discussion of this patterning of national history writing in the Romantic period, see Berger 2015b, chapter 3.

- Thaden 1999: 90ff. On the different positionings of Russian historiography towards ‘the West’, see also Nolte 1999.

- For a good introduction to Italian post-war historiography generally, see Pertici 2000.

- Smith 1959. One of the best examples of a social history critical of the national tradi-tion is Romano and Vivanti 1972–1978.

- The literature on the Historians’ Controversy is legion. Some of the most important documents of the debate can be found in English translation in Forever in the Shadow of Hitler? Original Documents of the Historikerstreit, the Controversy Concerning the Singularity of the Holocaust (1993); for two thoughtful book-length reflections on the debate in English compare also Evans 1989 and Maier 1989.

- Winkler 2000. The English translation is The Long Road West, 1789–1990 (2007); the French translation Histoire de l’Allemagne, XIXe-XXe siècle: le long chemin vers l’Occident, 2 vols (2005). See also Berger 2015a, for a detailed analysis and contextual-ization of Winkler’s volumes. For the renationalization of historical consciousness in Germany generally, see Berger 2003.

- Elton 1977 and Elton 1984. Elton, who was an immigrant with a Czech-Jewish back-ground, just like Namier, with a Polish-Jewish background, always felt very warmly towards the British nation – they both contrasted it positively with their East Central European homelands.

References

- Abbatista, G. (2012), ‘The Historical Thought of the French Philosophes’, in J. Rabasa, M. Sato, E. Tortarolo and D. Woolf (eds), Oxford History of Historical Writing, vol. 3, 406–27, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Adler, H. and Köpke, W., eds. (2008), A Companion to the Works of Johann Gottfried Herder, Rochester, NY: Camden House.

- Adler, H. and Menze, E. A. (1997), ‘On the Way to World History: Johann Gottfried Herder’, in H. Adler and E. A. Menze (eds), Johann Gottfried Herder on World History: an Anthology, 3–21, New York: M. E. Sharpe.

- Anderson, R. (2010), ‘University History Teaching and the Humboldtian Model in Scotland, 1858–1914’, History of Universities, 25 (1): 138–84.

- Baron, S. H. (1963), Plekhanov: The Father of Russian Marxism, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bentley, M. (2005), Modernizing England’s Past: English Historiography in the Age of Modernism, 1870–1970, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berger, S. (2003), The Search for Normality. National Identity and Historical Consciousness in Germany since 1800, 2nd edn, Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Berger, S. (2006), ‘On Taboos, Traumas and Other Myths: Why the Debate about German Victims of the Second World War is not a Historians’ Controversy’, in B. Niven (ed.), Germans as Victims: Remembering the Past in Contemporary Germany, 210–24, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Berger, S. (2015a), ‘Rising Like a Phoenix: the Renaissance of National History Writing in Britain and Germany since the 1980s’, in S. Berger and C. Lorenz (eds), Nationalizing the Past, 426–51, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Berger, S. (2015b), The Past as History: National Identity and Historical Consciousness in Modern Europe, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Berger, S. and Miller, A., eds. (2015), Nationalizing Empires, Budapest: Central European University Press.

- Berlin, I. (2000), Three Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder, London: Pimlico.

- Beyen, M. (2007), ‘Natural-Born Nations: National Historiography in Belgium and the Netherlands between a Tribal and a Social-Cultural Paradigm, 1900–1950’, Storia della Storiografia, 52: 17–25.

- Boia, L. (2001), History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness, Budapest: Central European University Press.Boyd, C. P. (1997), Historia Patria: Politics, History, and National Identity in Spain, 1875–1975, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bödeker, H. E., Iggers, G. G., Knudsen, J. B. and Reill P. H., eds. (1986), Aufklärung und Geschichte, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Brakensiek, S. and Flügel, A., eds. (2000), Regionalgeschichte in Europa, Paderborn: Schöningh.

- Braudel, F. (1986), L’Identité de la France, 2 vols, Paris: Flammarion.

- Cornelißen, C. and Ritter, G. (2001), Geschichtswissenschaft und Politik im 20. Jahrhundert, Düsseldorf: Droste.

- Durandin, C. (2002), ‘La function de l’histoire et le statut de l’historien à l’époque du national-communisme en Roumanie’, in M.-É. Ducreux and A. Marès (eds), Enjeux de l’histoire en Europe Centrale, 103–12, Paris: L‘Harmattan.

- Eckel, J. (2005), Hans Rothfels: eine intellektuelle Biographie im 20. Jahrhundert, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Elliott, G. (2010), Hobsbawm: History and Politics, London: Pluto.

- Elton, G. R. (1977), ‘The Historian’s Social Function’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 27 (5th series): 197–211.

- Elton, G. R. (1984), The Future of the Past, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Enteen, G. M. (1978), The Soviet Scholar-Bureaucrat: M. N. Pokrovskii and the Society of Marxist Historians, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press.

- Evans, R. J. (1989), In Hitler’s Shadow: West German Historians and the Attempt to Escape from the Nazi Past, London: Routledge.

- Feldner, H. (2010), ‘The New Scientificity in Historical Writing around 1800’, in S. Berger, H. Feldner and K. Passmore (eds), Writing History: Theory and Practice, 2nd edn, 3–21, London: Bloomsbury.

- Fichte, J. G. (2008 [1808]), Reden an die deutsche Nation, Hamburg: Rowohlt.

- Forever in the Shadow of Hitler? Original Documents of the Historikerstreit, the Controversy Concerning the Singularity of the Holocaust (1993), trans. K. James and C. Truett, Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press.

- Foster, R. (2002), The Irish Story: Telling Tales and Making It Up in Ireland, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Funke, P. (1998), ‘Das antike Griechenland: eine gescheiterte Nation? Zur Rezeption und Deutung der antiken griechischen Geschichte in der deutschen Historiographie des 19. Jahrhunderts’, Storia della Storiografia, 33: 17–32.

- Haapala, P. and Kaarninen, M. (2010), ‘Finland’, in I. Porciani and L. Raphael (eds), Atlas of European Historiography: The Making of a Profession, 1800–2005, 75, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harvey, J. L. (2003), ‘The Common Adventure of Mankind: Academic Internationalism and Western Historical Practice from Versailles to Potsdam’, Ph.D. diss., Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

- Hermann, I. and Metzger, F. (2015), ‘A Truculent Revenge: The Clergy and the Writing of National History’, in I. Porciani and J. Tollebeek (eds), Setting the Standards. Institutions, Networks and Communities of National Historiography, 313–29, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hernon Jr, J. M. (1976), ‘The Last Whig Historian and Consensus History’, American Historical Review, 81 (1): 66–97.

- Iggers, G. G. (1989), ‘New Directions in Historical Studies in the German Democratic Republic’, History and Theory, 28: 59–77.

- Kaye, H. J. (1984), British Marxist Historians: an Introductory Analysis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kellogg, F. (1990), A History of Romanian Historical Writing, Bakersfield, CA: Schlacks.

- Kiefer, R. (1989), Karl Bachem 1858–1945. Politiker und Historiker des Zentrums, Mainz: Koehler & Amelang.Kieser, H.-L. (2005), ‘Die Herausbildung des nationalistischen Geschichtsdiskurses in der Türkei (spätes 19.–Mitte 20. Jahrhundert)’, in M. Kroska and H.-C. Maner (eds), Beruf und Berufung. Geschichtswissenschaft und Nationsbildung in Ostmittel- und Su ̈dosteuropa im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, 59–98, Münster: Aschendorff.

- von Klimó, Á. (1999a), ‘Die gespaltene Vergangenheit: die grossen christlichen Kirchen im Kampf um die Nationalgeschichte Ungarns, 1920–1948’, Zeitschrift fu ̈r Geschichtswissenschaft, 47: 871–94.

- von Klimó, Á. (1999b), ‘St. Stephen’s Day: Politics and Religion in Twentieth-Century Hungary’, East Central Europe, 26: 15–29.

- von Klimó, Á. (2003), Nation, Konfession, Geschichte. Zur nationalen Geschichtskultur Ungarns im europäischen Kontext (1860–1948), Oldenburg: De Gryuter.

- Krumeich, G. (1996), ‘Ernest Lavisse und die Kritik an der deutschen “Kultur”, 1914–1918’, in W. J. Mommsen and E. Müller-Luckner (eds), Kultur und Krieg: die Rolle der Intellektuellen, Ku ̈nstler und Schriftsteller im Ersten Weltkrieg, 143–54, Munich: Oldenbourg.

- Leerssen, J. (2006), National Thought in Europe: A Cultural History, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.Levy, C. (1999), ‘Historians and the “First Republic”’, in S. Berger, M. Donovan and K. Passmore (eds), Writing National Histories: Western Europe since 1800, 265–78, London: Routledge.

- Liljefors, M. and Zander, U. (2004), ‘Der zweite Weltkrieg und die schwedische Utopie’, in M. Flacke (ed.), Mythen der Nationen – 1945: Arena der Erinnerungen, vol. 2, 569–92, Mainz: Koehler & Amelang.

- Maier, C. (1989), The Unmasterable Past: History, Holocaust and German National Identity, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Marchal, G. P. (2006), Schweizer Gebrauchsgeschichte. Geschichtsbilder, Mythenbildung und nationale Identität, Basel: Schwabe.

- Marjanović, V. (1998), Die Mitteleuropa-Idee und die Mitteleuropa-Politik Österreichs 1945–1995, Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

- McCartney, D. (1957), ‘The Writing of History in Ireland, 1800–1830’, Irish Historical Studies, 10: 347–62.

- Meinecke, F. (1915), Die deutsche Erhebung von 1914. Vorträge und Aufsätze, Stuttgart: Meinders & Elstermann.

- Mitchell, R. (2000), Picturing the Past: English History in Text and Image, 1830–1870, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morgan, P. (1999), ‘Reclaiming Italy? Antifascist Historians and History in “Justice and Liberty”’, in S. Berger, M. Donovan and K. Passmore (eds), Writing National Histories. Western Europe since 1800, 150–60, London: Routledge.

- Moses, J. A. (1975), The Politics of Illusion: The Fischer Controversy in German Historiography, London: Prior.

- Mühle, E. (2005), Fur Volk und deutschen Osten. Der Historiker Hermann Aubin und die deutsche Ostforschung, Düsseldorf: Droste.

- Murgescu, B. (2010), ‘Romania’, in I. Porciani and L. Raphael (eds), Atlas of European Historiography: The Making of a Profession, 1800–2005, 100, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mycock, A. and Loskoutova, M. (2015), ‘Nation, State and Empire: The Historiography of “High Imperialism” in the British and Russian Empires’, in S. Berger and C. Lorenz (eds), Nationalizing the Past, 233–58, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nisbet, H. B. (1999), ‘Herder: the Nation in History’, in M. Branch (ed.), National History and Identity: Approaches to the Writing of National History in the North-East Baltic Region: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, 78–96, Tampere: Finnish Literature Society.

- Nolte, H.-H. (1999), ‘Russia in Russian Writing of World History’, Storia della Storiografia, 35: 63–74.

- Otáhal, M. (1986), ‘The Manuscript Controversy in the Czech National Revival’, Cross-Currents, 5: 247–77.

- Pertici, R. (2000), Storici Italiani del Novecento, Pisa: Istituto editoriali e poligrafice internazionali.

- Petzold, S. (2011), ‘Fritz Fischer and the Rise of Critical Historiography in West Germany, 1945–1965’, Ph.D. diss., University of Aberystwyth, Aberystwyth, Wales.

- Reill, P. H. (1975), The German Enlightenment and the Rise of Historicism, New Haven: University of Berkeley Press.

- Riehl, W. H. (1897), Land und Leute, 9th edn, Stuttgart: Cotta’scher Verlag.

- Riehl, W. H. (1990), The Natural History of the German People, Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press (first published in German in four volumes, 1862–1869).

- Romano, R. and Vivanti, C., eds. (1972–1978), Storia d’Italia, 6 vols, Turin: Einaudi.

- Sartorius, N. and Alfaya, J. (1999), La Memoria Insumisa, Madrid: Espasa.

- Schwartz, B. (1982), ‘“The People” in History: The Communist Party Historians’ Group, 1945–1956’, in R. Johnson, G. McLennan, B. Schwartz and D. Sutton (eds), Making Histories: Studies in History-Writing and Politics, 44–95, London: Hutchinson.

- Shapira, A. and Penslar, D. J., eds. (2003), Israeli Historical Revisionism: From left to right, London: Routledge.

- Smith, D. M. (1959), Italy: a Modern History, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Šnē, A. (2010), ‘Latvia’, in I. Porciani and L. Raphael (eds), Atlas of European Historiography: The Making of a Profession, 1800–2005, 82, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Soffer, R. (2009), History, Historians, and Conservatism in Britain and America: from the Great War to Thatcher and Reagan, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stapleton, J. (2006), Sir Arthur Bryant and National History in Twentieth-Century Britain, Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Starkey, D. (2001), ‘The English Historians’ Role and the Place of History in English National Life’, The Historian, 71: 6–15.

- Stibbe, M. (2003), ‘German Historians’ Views of England During the First World War’, in S. Berger, P. Lambert and P. Schumann (eds), Historikerdialoge. Geschichte, Mythos und Gedächtnis im deutsch-britischen kulturellen Austausch, 1750–2000, 235–54, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Stora, B. (1999), Le transfert d’une mémoire. De l’Algérie française’ au racisme anti-arabe, Paris: La Découverte.

- Tanner, J. (2015), Geschichte der Schweiz im 20. Jahrhundert, Munich: C. H. Beck.

- Thaden, E. C. (1999), Rise of Historicism in Russia, New York: Peter Lang.

- Thiesse, A.-M. (1999), La Création des Identités Nationales. Europe XVIII–XIX Siècle, Paris: Seuil.

- Utgaard, P. (2003), Remembering and Forgetting Nazism. Education, National Identity and the Victim Myth in Postwar Austria, Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Wallace, S. (1988), War and the Image of Germany: British Academics, 1914–1918, Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd.

- Why We Are at War: Great Britain’s Case, by Members of the Oxford Faculty of Modern History; with an Appendix of Original Documents Including the Authorized English Translation of the White Book Issued by the German Government (1914), Oxford:Clarendon Press.

- Winkler, H. A. (1989), ‘Ein Erneuerer der Geschichtswissenschaft: Hans Rosenberg 1904–1988’, Historische Zeitschrift, 248: 529–55.

- Winkler, H. A. (2000), Der lange Weg nach Westen, 2 vols, Munich: C. H. Beck.

- Winkler, H. A. (2005), Histoire de l’Allemagne, XIXe-XXe siècle: le long chemin vers l’Occident, 2 vols, Paris: Fayard.

- Winkler, H. A. (2007), The Long Road West, 1789–1990, 2 vols, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zala, S. (2003), ‘Geltung und Grenzen schweizerischen Geschichtsmanagements’, in M. Sabrow, R. Jessen and K. G. Kracht (eds), Zeitgeschichte als Streitgeschichte. Grosse Kontroversen seit 1945, 306–25, Munich: C. H. Beck.

- Zetterberg, K. (1992), ‘Neutralitet till varje pris? Till frågan om den svenska säkerhetspolitiken 1940–42 och eftergifterna till Tyksland’, in B. Hugemark (ed.), I Orkanens Őga: 1941 – osäker neutralitet, 11–36, Stockholm: Probus.

- Zsolt, B. (2010), ‘The Small Mirror of Hungarian Literature’, in A. Ersoy, M. Górny and V. Kechriotis (eds), Modernism: Representations of National Culture, vol. III/2 of Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeastern Europe (1770–1945): Texts and Commentaries, 26–32, Budapest: Central European University Press.

Chapter 13 (239-259) from Roman Law and the Idea of Europe, edited by Kaius Tuori and Heta Björklund (Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 license.