How did the Middle Ages define childhood and distinguish it from either infancy or adulthood?

By Dr. Nicole Clifton

Professor of Medieval Literature and Language

Co-Director of the Medieval Studies Concentration

Northern Illinois University

Introduction

“Childhood, as we now think of that period between infancy and adulthood, is an invention of the eighteenth century in those very few countries of Western Europe that could afford leisure and were dedicated to creating and confirming a middle-class elite.”1 This statement accompanies an exhibit on illustrated children’s books, “Picturing Childhood,” at UCLA. It appears to make a number of assumptions: that the Middle Ages had no special term for the “period between infancy and adulthood” (not true); that childhood labor was widespread prior to the Industrial Revolution (medieval children did work that was suited to their immature bodies and minds, but were not expected to manage the crippling workloads of nineteenth century chimney sweeps); that special consideration allotted to childhood is a trait linked to the growth of the middle classes (apparently aristocratic children are as oppressed as lower-class ones). This strongly Marxist view of the past neglects the important point that the Middle Ages, because they were not industrialized, did not have the kind of underclass that marks the industrialized world. To be sure, the poor they had always with them; but then children and adults suffered alike, and were not so numerous, except in famine years, that there was no chance of alms. Before the Reformation, indeed, poverty was less likely to be seen as God’s judgment, and the poor more likely to be viewed as opportunities to give alms and thus save one’s soul.

Although Philippe Aries’s name does not appear on the exhibit website, his influence is obvious. His claim—as it has been understood by Anglophone readers—caught readers’ imaginations precisely because it was both sweeping and shocking, stressing the alterity of the Middle Ages (despite his accompanying caveat that certainly medieval people did feel affection for children).2 Scholars, of course, challenged the claims of Centuries of Childhood from an early date. In 1967, Irene Quenzler Brown said, “if one seeks to reconstruct the status of the child at any given period on the basis of Aries’s assorted evidence, one meets vagueness and even inconsistency;”3 she also notes that his “insular approach has not acquainted him with the basic innovations in pedagogy and child psychology made … in the fifteenth century, innovations based precisely on the acceptance of the special nature of childhood” (362). Although journals of medieval studies, such as Speculum, failed to review a book that focused on the seventeenth and later centuries, by 1980 Adrian Wilson could produce a scathing overview of the first twenty years of Aries reception, noting objections from such disparate sources as Natalie Zemon Davis, Lloyd deMause, and Lawrence Stone, who, though they all work on childhood and adolescence, take notably different approaches to the subject.4

In fact I generally agree with parts of the UCLA statement, if re-phrased something like this: “in the industrialized world, the middle and upper classes mark themselves off from the working and under classes by privileging the lives of their children and women, giving them special roles, clothing, space, and occupations (or non-occupations).” But this statement does not speak to the Middle Ages. What we must ask, instead, is “How did the Middle Ages define childhood and distinguish it from either infancy or adulthood? How did medieval people educate and entertain their children? How did the figure of the child function in literary contexts, and what does this imply about the conception of childhood? What special accommodations did literature and other areas make for children?”

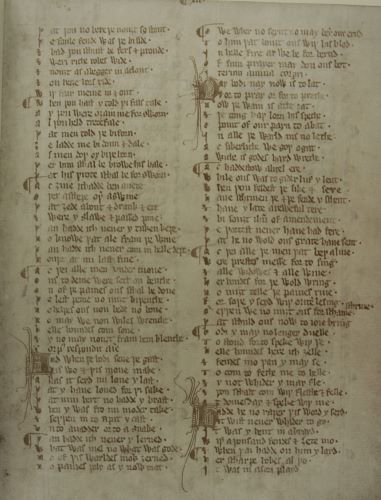

‘The Seven Sages’ and the Auchinleck Manuscript

I contend that the well-known Auchinleck manuscript (Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland, Advocates MS. 19.2.1),5 long considered as an important repository of medieval English romances and related materials such as saints’ lives, testifies to a serious and sustained production and appreciation of medieval children’s literature. I base this contention on the following considerations: the entire manuscript is in English, suggesting readers uncomfortable with French or Latin; many of the texts contain didactic elements of the sort to be found in courtesy books aimed at children and teenagers; in some cases, literary texts elaborate on material from purely didactic texts also in the Auchinleck manuscript, in a way calculated to excite interest and reinforce learning in young readers or hearers; many of the texts have children as protagonists or in important symbolic roles; the style and contents of many texts share characteristics of children’s literature as it is presently defined; subject matter, particularly when compared to Old French sources, appears to have been adapted for unsophisticated readers. Scholars have long leveled this criticism at many medieval English romances (with exceptions such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight), but traditionally the audience for these romances has been understood to be lower-class or upwardly mobile adults. I argue that children are a more likely audience for these texts, and that in particular, The Seven Sages of Rome seems well-fitted to be family literature, addressing a wide range of interests and suggesting possibilities for interpreting other texts in the manuscript.

This frame story, imported from the East, was known throughout Europe. It involves a prince, educated by seven masters, whose stepmother falsely accuses him of rape. To save the boy, who has foreseen that he will be safe if he does not speak for a week, each sage in turn tells a story urging the emperor not to trust his wife, while the stepmother each night counters with a story against either the boy or the masters. Finally the prince speaks on his own behalf, and his father puts his wife to death and reconciles with his son.

The seven-days framework invites us to see the inner stories as paired texts, commenting on each other. Moreover, we should attend not only to the implica-tions of these stories’ relationships to one another, but also to consider the effects of such a reading on the interpretation of the manuscript as a literary whole. The Seven Sages, originally item 25 in the Auchinleck manuscript, is now item 18—a bit less than halfway through—following a long run of mainly religious works and preceding a number of romances and other secular texts. Its position, therefore, may encourage readers to reflect on both earlier and later items in the book. It evokes or foreshadows other texts in the Auchinleck manuscript, particularly Floris and Blauncheflor, which immediately follows Seven Sages (a gathering is missing at the beginning of Floris, but it presumably begins similarly to the other ME MSS). The two stories share pleasant-sounding schooling and an exotic setting, as well as having protagonists with very similar names. Furthermore, both feature courts who have mercy on children despite the rulers’ plans to kill the young people. The seductive stepmother of Seven Sages may be an in malo version of Blauncheflor, who is perfectly loyal and long-suffering. The introductory sections about masters and schooling seem to aim at parents or guardians who supervise education.

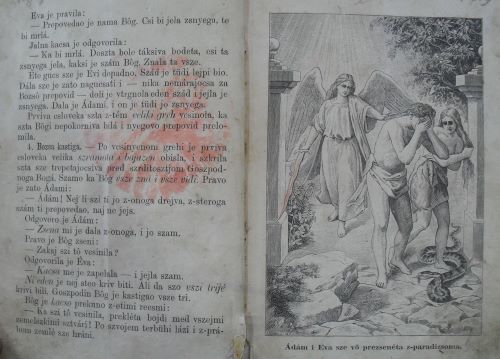

Seven Sages also refers to the romance Of Arthour and of Merlin, which appears later in the book. One of the internal stories, told by the empress, features Merlin, the child without a father, who cures an emperor of his blindness by advising that he kill his seven wise men. Merlin also appears as a main character in Arthour and Merlin, where his ambiguous parentage receives considerable attention. Another internal story in Seven Sages involves an adulterously begotten child, calling both Merlin and Arthur to mind. Many of the internal stories, in fact, involve children, usually sons or nephews. Of course the frame demands stories that alternately praise and revile the young, but the Auchinleck manuscript as a whole contains many stories where children play an important part. The Life of Adam and Eve, for example, devotes about a third of its length to their son, Seth.

The original owner of the manuscript, who may have commissioned it for a particular purpose, selected the texts it contains. Many of them, including the Seven Sages, translate popular French or Latin texts into English. I believe that many such translations were made not for upwardly mobile bourgeois audiences who did not know French—because many people in that class did know French6—but for children raised in English-speaking households who might learn French later, as an accomplishment. These might include girls who were educated at home, while their brothers learned Latin and French at school.

The Auchinleck manuscript is a fairly large volume, its 331 extant folios now measuring 250 χ 190 mm (about 10 inches by 71/2; the pages have been trimmed); smaller than “coffee-table size,” it remains a hefty book. The manuscript has lost a number of folios, and unknown items with them: the present first text has the number 6 at its head. Seventeen or more texts may have been lost, yet at 43 items, the Auchinleck is a treasure trove of Middle English literature. Entirely on parchment, entirely in English, dating to the decade between 1330-1340, illustrated (much manuscript damage is due to illuminations having been cut out), this book appears to have been produced by a lay establishment, in London, for a wealthy patron. Timothy Shonk estimates its original cost at around ten pounds.7 To give an idea of contemporary buying power, during the fourteenth century the English crown encouraged any man with a landed income of over 40 pounds a year to become a knight, while by 1400 esquires were worth 20 to 40 pounds per year and gentlemen from 10 to 20 pounds.8 The book would have been a considerable investment, probably treasured within generations of a family. However, we know nothing of its orginal patron or scribes.

Some hundred years after the manuscript’s creation, a fifteenth century reader recorded the names of a family on folio 107 of the manuscript. Following the Norman names of the Battle Abbey Roll, in a firm hand, the following names appear: Mr Thomas and Mrs Isabel Browne, Katherine, Eistre, Elizabeth, Walter, William, Thomas, and Agnes Browne. This list suggests that during the 15th century, the manuscript belonged to a family—a large family, with children of varying ages to be educated and entertained. Thus the manuscript’s contents are, in late medieval England, demonstrably children’s literature in the sense that they had an audience of young people. Unfortunately, the Brownes’ name is so common as to hide them from historians’ scrutiny, yet the list itself tells us something about them. The name Browne follows each of the children’s names, so either all seven were unmarried when this inscription was made, or the writer thought of the family as a unit, even if the older girls had married. The number of children might suggest a gentry family, since city merchants often had smaller families, but this is uncertain. If all the children listed were living, the Brownes were fortunate, and perhaps the inscriber was celebrating this fortune; if some died young, it is significant that the writer of the names thought of them all as a family unit, whether alive or dead. The Brownes were sufficiently well off to own or have access to this book; if it did not pass from generation to generation of this family, perhaps it came to them by will, by gift, or as security for a loan. At least some of them were writers as well as readers: the hand that wrote the name is steady and practiced, if not a book hand. I propose to keep the ghostly Brownes in mind as I pursue my reading of the Seven Sages of Rome: what would the boys and girls and parents find to appreciate in this text?

But first, an excursus: what is children’s literature?

Definitions of Children’s Literature

Obviously there are problems in defining children’s literature: it is not produced by children, or even chosen by children, but by adults. Adults are, therefore, always at some level in the audience for children’s literature, whether as procurers (parents, librarians), as readers-aloud, or as fans (for example, adults who read Harry Potter novels for their own pleasure). This pleasure can be nostalgic or participate in the pleasure inspired by genres such as fantasy (arguably the modern version of romance), but it should not be dismissed. Adults who select children’s literature for their own reading material may very well have other criteria in mind than those who pick out stories for children—even when these categories overlap. Nonetheless, most critics agree on a certain constellation of traits that characterize children’s literature. As with a medical syndrome, any one or two of these traits do not define the genre, but a large selection of them indicate a high likelihood that a text was written for, or would likely be appreciated by, children.

First, in fiction, child or animal protagonists are the rule. Some fiction for adults does use children as protagonists; for example, Carson McCullers’ The Member of the Wedding. Moreover, mainstream novels often begin with the protagonist’s childhood before considering her or his adult life. However, very few texts for children focus entirely on the activities of adults. Animals are a somewhat ambiguous category, but theorists of children’s literature classify animals with children: in a world where adult humans are in control, children and animals (even talking ones) are equally at their mercy. Human characters who intrude into imaginary worlds inhabited by animals, such as the washerwoman in The Wind in the Willows, are usually servants or in some other way rendered inferior to the animals, just as servants would be the inferiors of upper-class children. Children demonstrably take greater interest in other children than they do in adults; similarly, they respond to the presence of children in literature—even in literature not originally intended for them.

Children’s fiction also tends to emphasize action rather than reflection, a point so widely accepted that few critics dilate on it, preferring to move on to related notions like theme or structure. This emphasis on narrative perhaps explains why critics have tended to marginalize children’s literature, along with other genres that stress plot over other literary considerations. I would like to note in passing that ther e is a high degree of permeability between fantasy and children’s literature, which share an interest in both plot and magic. As for the sort of plot structure common in children’s literature, it is frequently circular, following what Perry Nodelman describes as a “home/away/home” pattern, in which characters learn the value of home; Nodelman adds that if leaving home leads to maturation, then the story is for adults, while if “escape allows the preservation of some form of innocence,” the story is most likely for adolescents.9

The word “simplicity” often appears in definitions of children’s literature, in various contexts. The moral outlook of children’s literature is simple, black and white, rather than delicately nuanced. The fictional world may be violent, as in traditional fairy tales, but whatever is wicked is clearly defined, and punished. Children’s literature uses simple language, so that it will be easier to understand, and it makes points more explicitly, rather than proceeding by implication or indirection. Myles McDowell suggests that “conventions are much used” but Hunt shows how complicated these conventions can appear to readers unequipped with previous knowledge of them.10

It will now be apparent that many definitions of children’s literature rely on nineteenth and twentieth century examples; in fact, children’s literature scholars often accept Aries’s thesis unquestioningly and assume the genre begins with the Puritans’ tracts of the seventeenth century. These tracts, of course, do show the characteristics listed above: they tell stories about children, in simple language, in a very clear moral universe, and they focus on actions, the purported actions of real children, such as praying, rebuking friends for frivolous behavior, and going to church. These are not exciting actions, compared to twentieth-century books for children, but they are actions, stories—exempla—rather than sermons; we see children praying, rather than an author urging prayer upon his readers.

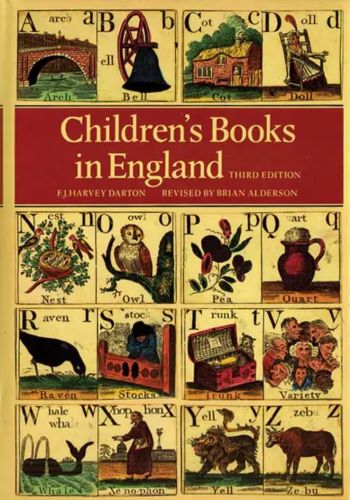

Moreover, those who consider the full range of children’s literature, like Harvey Darton11 (the locus classicus), agree that folktale, fairy tale, and medieval romance were read and loved by children. The crucial distinction, for these scholars, is that these tales did not aim solely at children, but could be enjoyed by a wide audience. Critics who dismiss the possibility of early children’s literature may simply wish to address solely texts that demonstrably aim to entertain and instruct children alone, not adults as well. However, as noted above, those who write for children necessarily also write for adults, as adults buy (and read) almost all the children’s literature sold. Therefore, any children’s literature at some point considers its adult audience (even if it is the publisher rather than the author that pays most attention to this consideration). The chapbook might comprise an exception to this rule, in that it was cheap enough that children of the tween years might acquire their own chapbooks without reference to disapproving adults, but this point need not delay us here.

In fact, “family literature”—works appreciated by a broad age range—requires closer consideration to determine the characteristics that address adult and child constituencies, to enumerate the techniques used to keep the attention of all segments of its audience, and to evaluate the effectiveness of these techniques. In addition, we need to think about the implications of certain kinds of texts being family literature: what will different members of a family, at different ages, get out of medieval romances, fairy tales, legends, and so on? How do these texts interact with others, popular or learned, used in schools or in church, that readers might already know or be likely to read later? What does “family literature” teach, and how? Why and how is it entertaining? These questions have yet to be explored; this essay is a beginning on the problem, which I will deal with at greater length elsewhere.12

The difficulties of defining children’s literature through its content have led certain critics—most notably Barbara Wall, Aidan Chambers and Peter Hunt—to focus on questions of audience and voicing. Children’s literature, in contrast to works for adults, fills in more “gaps;” it draws conclusions that experienced readers could infer for themselves, provides more explicit comparisons, makes the attitudes of narrator and characters clearer. For example, Chambers studies passages from a Roald Dahl story re-written for children, comparing the earlier “adult” version. The children’s version replaces irony with straightforward reporting, removes abstractions, and simplifies sentences; Chambers identifies the tone as “clear, uncluttered, unobtrusive, not very demanding linguistically.”13 Even without multiple versions, we can see when writers fill in background that older or more experienced readers would already know, or would know how to fill in from context, as Chambers shows in his analysis of L. M. Boston’s voice in the Green Knowe books.14 On the other hand, classic children’s books such as those by Beatrice Potter have far more gaps than their modern retellings, as Peter Hunt demonstrates; modern versions explain motivation—”So Mrs Rabbit decided to give Peter something to make him feel better” — where Potter allowed audiences to deduce these elements: “Peter was not very well during the evening. His mother put him to bed, and made some camomile tea; and she gave a dose of it to Peter!”15

So considering audience, and gaps, does not always allow us to draw clear, simple distinctions between texts for adults and those for children. What of the stories that both children and adults read for pleasure? What makes them accessible and enjoyable for a broad audience? Barbara Wall studies the question in terms of narratorial voice, which she separates into the categories single, double, and dual.16 Single address, Wall says, is a 20th century development in which children are the only audience considered, and which treats them respectfully and seriously. This voice explains, but does not condescend. Double address shows awareness of adults in the audience of a work meant for children; this voice speaks over the head of children to these adults, inserting jokes or asides meant to entertain those who would be bored by the main story, while it shows self-consciousness in its attention to children. Although Victorian writers most notoriously use double address, it continues to appear in modern works, including film and cartoons. Wall finds that dual address is the most rare; this voice takes children and adults equally seriously, considering the needs of both kinds of readers, without talking down to anyone or creating an alliance between adult-narrator and adult-reader that ignores children, even temporarily.

In medieval literature for (or read by) children, we are most likely to find double address, allowing older and younger audiences to read a scene differently and appreciate different elements of it. Occasionally we find a writer referring to children directly—though not necessarily addressing them—as in the prologue of the romance Of Arthour and of Merlin (another Auchinleck text).

Childer pat ben to boke ysett

In age hem is miche pe bett

For zai mo witen and se

Miche of Godes priuete

Hem to kepe and to ware

Fram sinne and fram warldes care.17

The narrator implies that children who read Arthour and Merlin will be the better for it; he may reassure guardians or teachers, or he may include children in the audience to the prologue.

For be wrytinge we moste lere

How we moste gouerned be

To worshyppe Gode in trinite.

And ther-fore Stories for to rede

Wolle I conselle, withowten drede,

Bothe olde and yonge pat letteryd be.18

The narrator of The Seven Sages of Rome does not include such explicit addresses to children (in manuscripts where the beginning is extant: the Auchinleck text begins at line 120 of the standard edition). Nonetheless, I argue that this text does contain examples of dual address, one of which I shall examine below.

‘Seven Sages’ as Children’s Literature

It might seem that a story whose protagonist is accused of rape must necessarily address adults, not children: the hero is sexually mature, if not full-grown—old enough to make the accusation plausible, at any rate—and few modern readers would consider the subject matter suitable for children. To answer the second objection first, such standards vary. The Middle Ages were not so mealy-mouthed with their children as the nineteenth and later centuries have been; consider the stories collected by the Knight of the Tower for his daughters.19 Many of these have explicit sexual content, and aim to teach young women not just the desirability but the necessity for chastity and a close guard on it. Moreover, Mary E. Shaner has shown that one version of Sir Gowther, whose hero truly is a rapist, was directed at an audience of children.20 Sir Gowther’s demonic heritage inspires him, as an infant, to bite off his mother’s nipple, and as an adult to pillage and rape a convent of nuns. One extant manuscript leaves out this last detail; the other, included in an “anthology” manuscript containing three conduct manuals and three romances, develops it in gloating detail. Shaner argues that the romances of this manuscript are youthful readers’ reward for getting through the conduct manuals, that the violence and uproar of Sir Gowther would appeal to an audience of boys.21 Sir Gowther, of course, repents and does penance, so that the tale ultimately celebrates his submission to God rather than his appalling youthful exploits. Along similar lines, I would argue that since Florentyn is actually innocent, we see him as someone who patiently suffers the ill brought on him by others, rather than as a negative example; and that the message is that innocence will triumph.

Although Florentyn’s age during the main action of the tale may cast him as a young adult, the story and its characters present him always in a filial relationship, emphasizing his position as part of a younger generation, dependent upon the older. The inner stories, many of which involve conflicts between youth and age, reinforce this emphasis. The story opens with sending Florentyn to school, which invites us to see him as childish and in need of training. When he surpasses his masters by the age of 15, his precocity is meant to be astonishing, to make him stand out from other characters. His ability to outwit an adult plot against his life places him in the category of young heroes who are both unusual and capable of far more than adults expect of them—rather like Harry Potter. As with much “subversive” children’s fiction [see chapter one of Alison Lurie’s Don’t Tell the Grown-Ups (Boston: Little, Brown, 1990)], this young hero is more than a match for his elders.

Returning to the problem of the accusation of rape, the jealous empress is provoked by a servant who suggests that the existence of a previous heir will make her children bastards:

Som squier or som seriant nice

Auch. 239-46; 249-52

Had itold Jsemperice

Al of Jsemperoures sone,

Hou he wi3 be maistres wone.

And hire schildre scolde be bastards

And he schal haue al pe wardes

Vnder hest and vnder hond

Of empire and al jse lond.

…………………………………..

And Jjoughte, so stepmoder doz

Into falsenesse [to] torne soz

And brew swich a beuerage

at scholde Florentin bicache

This description “fills gaps” in a way characteristic of children’s literature. The empress’s anxieties are spelled out, not implied. Moreover, not actions but explicit labels establish characterization: the servant is “nice,” while the empress, in the folkloric tradition of stepmothers, plans “falsenesse.” When she is alone with Florentyn, “ye emperice was queinte in dede / And [in] hire wrenche and in hire falshede” (425-6). The seduction attempt, in fact, seems designed to fail or at least to remain incomplete: she wants not to lie with Florentyn but to make him speak, or, failing that, to be able to accuse him of rape. In other words, the focus is not on sex but on duplicity.

The details of this scene emphasize humor rather than violence, in a way that may function differently for audiences of different ages. The empress relies on speech as well as gesture: alone with Florentyn, she sits by him, looks at him, and claims to have kept her virginity for him, since her husband is “of bodi cold” (436). At the end of this speech, she puts her arms around F’s neck. When she rends her clothing, following his wordless rejection, she seems to have enough layers on that it should require considerable effort to get through them all, adding a comic element that shows her as laughable as well as false.

Sehe tar hire her and ek here cloz,

458-62; italics mine

Here kirtel, here pilche of ermine,

Here keuerchefs of silk, here smok ο line,

Al togidere, wi3 boze fest,

Sehe torent binezen here brest.

As we have seen, some stories deliberately address both children and adults, sometimes speaking over the heads of children in their audience (double address, in Barbara Wall’s terms), sometimes managing to treat the interests of both with equal respect (dual address). Here, I argue, we have an example of double address, where a younger reader would respond to the surface of the story—the danger to Florentyn, the suspense as to whether he will speak, the comedy of the empress’s struggle to rip so much clothing all at once—while an older one would notice the absence of any language indicating desire or sensuality. The empress speaks to Florentyn almost as if to a child—”mi leue suete grom” (431)—and demands “kes me . . . and loue me” (443). We are a long way from the stress on pleasure in a similar scene in the Old French Roman de Silence.22 The fact of sexuality is not glossed over, but details are.

Finally, the Auchinleck text alone contains the lines of the emperor to the second master,

“Ich tok ze mi sone to lore

973-8

For to teche him wisdom more

And 3e han him bitreid;

His speche is loren, ich am desmaid.

Mi wif he wolde haue forht itake.

To de3” he seide “he schal ben don wi3 wrake.”

Brunner reads this as a direct accusation of the masters’ having incited the rape;23 the Ε manuscript (London, British Library, Egerton 1995 [later fifteenth century]) reinforces this view with the line “And lechery ye haue hym teche” (986). I wish to emphasize the father’s desire to lay the greatest blame elsewhere than on his son. He seems to be trying to find a way around punishing his son, showing his concern and love for the boy.

Both frame and inner stories emphasize action, often structured around the home/away/home that Nodelman observes is common in children’s literature. (Not that no adult fiction uses that structure, but recall that definitions of children’s literature look at a constellation of traits.) The frame story begins with Florentyn going away to school, and ends with his triumphal reintegration into the court, after a week’s iteration of the leaving/returning pattern as his jailers bring him to court and take him away again.24 Each day, the audience wonders whether he will keep his resolution to stay silent, whether his father will reprieve him again: though the action is predictable, it is also suspenseful. Florentyn’s original departure for school is not escape, but an opportunity for maturation, which in Nodelman’s terms suggests a story for adults. At the same time, however, restoration to home does preserve innocence, very literally: Florentyn proves innocent of the crime imputed to him by his stepmother, and returns to his position as his father’s sole heir. Nodelman might argue that this suggests a story for adolescents, while a story for children would convey the message that home, “representative of adult values” is better, safer, than the outside world.25 In fact, this story has the hero returning to cleanse home of evil influences—like various other romances in the Auchinleck manuscript—but I want to emphasize that Florentyn needs the help of his masters to win the day, that he cannot manage this feat on his own, an d that far from overthrowing his father, he seeks only restoration to his former status as beloved and dutiful son. The frame structure, then, has something for everyone: this is family literature.

The framed stories similarly address a variety of interests in both structure and content. Stories told by the stepmother, of course, tend to present youths who contribute to the undoing of their elders, while stories told by the sages stress the perfidy of women. Yet other themes run through these tales, in some cases subverting, answering, or distracting from the overt message. The stories of faithful animals falsely accused by women and killed by their masters (canis, avis), for example, make a strong case for checking one’s evidence and not relying on hearsay—never mind whose testimony is at fault—or simply for not acting in anger or grief, but restraining initial emotional impulses. Such points about self-control might well appear in didactic children’s literature, while a child reader might be amused by the cleverness of the wife’s tactics in the bird story, or respond emotionally to the faithful greyhound, just as later generations have to Black Beauty, another tragic animal tale.

The tales told by the stepmother have the obvious appeal of young main characters, who, moreover, always triumph over their aged uncles, fathers or other authority figures. Thus young readers might understand these tales differently from how the empress means them, as warnings to her husband not to trust his son. Her first story, for example, about the “ympe” that ultimately kills its parent tree, might be read in various other ways: as advice on gardening (if you want to keep your big old trees alive, cut down shoots; alternatively, if you want to replace your old, unhealthy trees, prune them so as to allow their shoots light and air); as an exemplum about obedience not always being desirable (what if the gardener had persuaded the merchant to rescind his order to cut the branch shadowing the young shoot?); as a parable about the risks of getting what you think you want—it is, after all, the merchant who orders that his old pine be pruned, not the “ympe” that chokes it out without help. As Jaunzems observes, the “crime” of both the shoot and Florentyn is simply that they exist, and the stepmother sometimes deploys her tales illogically ,26 This element, too, could be used as a teaching device, offering readers who “unto logyk hadde … ygo”27 a chance to test their skills on these vernacular texts.

The first master’s tale, which answers the stepmother’s story about the tree, has a much clearer moral (briefly discussed above). A knight’s dog saves his child from a snake; but the nurses and mother panic when they find blood on the dog’s snout and the cradle overturned, and tell the father that his favorite dog killed the infant. The knight kills the dog, only to discover the body of the snake by the cradle that still shelters the child, and bitterly regrets his hasty actions. The tale gives considerable detail about the knight’s domestic establishment; for instance, his child has three nurses, one to give suck and the other two to bathe the baby (713-7). In relating the struggle between the snake and the greyhound over the cradle, the narrator assures us that the “ye stapeles hit vp held al quert” (757), so that the cradle continues to protect the infant. These details suggest interest in nursery arrangements and a desire to alleviate anxiety about the child’s fate. The knight’s feelings, however, are strongest for his greyhound; in the end, he goes barefoot into a forest to become a hermit. The emphasis of this tale on such details, combined with the vigorous action of the fight between the two animals, strongly suggest an appeal to children and their interests.

By the fifteenth century, when the Brownes owned the manuscript, literacy was more widespread than in the early fourteenth century, and book production had increased. Older stories continued to be copied—and, eventually, printed—but Chaucer and other Ricardian authors had changed the face of literature. Readers familiar with The Canterbury Tales will perceive a frame story like the Seven Sages differently from earlier readers. The internal stories of the Seven Sages come in pairs, share obvious themes and build to an expected conclusion. The stories of the Canterbury Tales do not all connect in obvious ways, but force a reader to think about thematic similarities. The Seven Sages might suggest other reading possibilities to sophisticated readers, such as considering that the texts that follow it might also be read in pairs, as stories that answer each other. Up to a point where at least five gatherings have been lost, seven neat pairs of texts follow the Seven Sages in the Auchinleck manuscript.

Following Floris and Blauncheflour, a romance about educated children who reform and convert a capricious emir, comes “The Sayings of the Four Philosophers,” a poem classified with prophecies or satires: four wise men gloss their gnomic utterances to explain why England is in bad shape and why love of God is paramount. It applies the lessons of Floris to a domestic setting. Next we have the Battle Abbey Roll, a list of names of Norman barons, followed by the first, couplet version of Guy of Warwick. This pairing inverts the previous one, in that it begins with an evocation of domestic aristocratic history, followed by a romanced version of English history, a foundation story for the earls of Warwick. The thematic connections between the next two texts, the second half of Guy, in stanzas, and the story of Reinbroun, his son, are obvious. Sir Beves of Hampton and Of Arthour and of Merlin are both, for medieval English readers, historical romances, both involving disinherited sons who must fight to regain their heritage as adults.

Of the next pair, “The Wench that Loved the King” is almost entirely destroyed; fragments of words remain that suggest England as a setting, and that money changed hands. “A Penniworth of Witt” tells of a merchant with both wife and lover, and how he learned to appreciate his wife’s loyalty more than his lover’s avarice and self-interest, through the advice of an old man met in a bar. It seems likely that “Penniworth” is a more moral answer to the fabliau that preceded it. The miracle story “How Our Lady’s Psalter Was First Found” and Lai le Freine both involve abbeys, children given up or abandoned, and the making whole of what was damaged; one uses a purely religious context, one is a more secular story. Finally appear the pair of romances Roland and Vernagu and Otuel a Knight, both based on the Old French Charlemagne cycle of chansons de geste. Besides their common setting and characters, they follow the general pattern of one more pointedly moral or practical text alongside one more strongly fictional or entertaining28: Roland teaches many basic tenets of the Christian faith to a Saracen knight, reinforcing the learning one might get in “The Paternoster Undo on Englissh” (the third work before Seven Sages), while Otuel, a longer tale, places a much greater emphasis on action.

Although I cannot develop here all the implications of these paired texts, both in their pairs and as a group, I believe that one way the Auchinleck manuscript served its family audience was by providing such pairs following the “key text” of the Seven Sages of Rome. Whether or not the original patron thought of using the Seven Sages in this way, an educated fifteenth-century audience would be very likely to see this possibility. These sets of texts allow more sophisticated readers to tease out the possible connections and probe for deeper insight into these works’ lessons, while younger or less cultivated readers would focus more narrowly on the texts of particular interest or value for them: those introducing them to texts they might later read in French or Latin, those with young characters and plenty of action, and those that reinforce what they have learned in other contexts. Thus readers of different ages and backgrounds can all enjoy and profit from the same texts, from their different perspectives.29

The Browne family had three sons to bring up to suitable careers, and four daughters to prepare for marriage. If I may, for a moment, imagine them all alive at the same time, ranging in age from adolescence down to a toddler, gathering in their home to hear a parent, tutor, or chaplain read to them from the Seven Sages of Rome, this is the picture I see: the oldest girls, Katherine and Eistre, whose marriages will soon be negotiated, focus on the relationship between the emperor and his wife. Their mother will ask them what lessons they learn from the wicked stepmother, from the wives of the various inner tales, and they will say they have learned not to leap to judgment or use their ingenuity to bad ends, but rather to ascertain the facts of a situation, to respect their husbands and be faithful, to use their influence over husbands and households wisely. The next child, Elizabeth, and the oldest boy, Walter, have not yet reached their teens. Elizabeth should be thinking about the same points as her older sisters, but she and Walter have learned the game of working out a tale’s moral and compete to predict the point of the tales told by the empress and the sages; at first they are quite serious, but then they begin to invent silly morals and have to be rebuked. William has started school fairly recently; he wishes he had masters who knew such good stories, and he also wishes to own a good, loyal hound who would attack his enemies. Or he will be the hound, and attack Thomas, the serpent. Thomas is unprepared for this, since he was daydreaming about climbing the enormous pine tree of the empress’s first story; both boys fall over Agnes before Katherine can snatch her out of harm’s way. To the accompaniment of Agnes’s wails, the three younger children are taken away to bed, where they must say their prayers and Creed. Thomas insists on instructing a toy soldier in the Creed, making believe that this is Otuel, and he Roland.

However fanciful, this picture reminds us that “children” are not a unitary audience, but individuals with different abilities and interests. In the Middle Ages, a girl of fifteen is both old enough to be married and young enough to require further instruction, as the Menagier de Paris’s treatise shows (in fact, he includes and adapts certain tales from the Roman des Sept Sages).30 Her five-year-old brother may not care for, or even be able to understand, the tales she enjoys. I think that the Seven Sages of Rome would likely not be appreciated by young children, except perhaps as intermittent images or pieces of stories might catch their attention. Somewhat older children would be entertained by elements such as the elaborate efforts to convince the husband in avis that his bird had ceased to tell the truth (climbing on the roof, pouring water through a hole in it, making noise to simulate thunder), although they, too, might not comprehend the full implications of the tale. At a later stage of development, children will begin to put the pieces together, to appreciate both plot and morals, and even to analyze tales’ morals and logic. The attention of an older person—parent or teacher—to this process will, of course, influence what younger readers are able to perceive, and at what ages they will do so. The framework of The Seven Sages of Rome, including a family and schooling, encourages such attention to the inner stories and their relationship to each other, and encourages learning to think about tales’ morals (which often appear at the end of medieval texts, as do, for example, the allegories in the Ovide Moralise:31); guardians alert to opportunities for moral education might encourage similar moralizing about the romances in the Auchinleck manuscript. The Seven Sages is placed in the manuscript in such a way as to invite both reflection on the holy legends that precede it, and anticipation of ways to interpret the romances that follow it; it is itself both didactic and pleasurable—the number of translations and analogs attest to its popularity around the medieval world; and in themes, narrative organization, and voice it seems well suited to family audiences including children and young adults, as well as those who care for them.

Endnotes

- David Rodes and Gloria Werner, http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/childhood/fore.htm (last accessed on March 14, 2005).

- Philippe Aries, Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life, trans. Robert Baldick (New York: Random House, 1962), 128.

- Irene Quenzler Brown, Review of Centuries of Childhood, by Philippe Aries, History of Education Quarterly 7 (1967): 357-68; here 358.

- Adrian Wilson, “The Infancy of the History of Childhood: An Appraisal of Philippe Aries,” History and Theory 19, 2 (1980): 132-53; Natalie Zemon Davis, “The Reasons of Misrule: Youth Groups and Charivaris in Sixteenth-Century France,” Past and Present 50 (1971): 41-75; Lloyd deMause, “The Evolution of Childhood,” History of Childhood Quarterly 1 (1974): 503-606; Lawrence Stone, Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800 (New York: Harper and Row, 1977).

- See also the on-line edition at http://www.nls.uk/auchinleck/ (last accessed on March 14, 2005).

- See, for example, Peter Coss, “Aspects of Cultural Diffusion in Medieval England: The Early Romances, Local Society, and Robin Hood,” Past and Present 108 (1985): 35-79, and Nigel Wilkins, “Music and Poetry at Court: England and France in the Late Middle Ages,” English Court Culture in the Later Middle Ages, ed. V. J. Scattergood and J. W. Sherborne (London: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 183-204.

- Timothy A. Shonk, “A Study of the Auchinleck Manuscript: Bookmen and Bookmaking in the Early Fourteenth Century,” Speculum 60 (1985): 71-91; here 89.

- W. M. Ormrod, The Reign of Edward III: Crown and Political Society in England 1327-1377 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 148.

- Perry Nodelman, The Pleasures of Children’s Literature (White Plains, NY : Longman, 1996), 155.

- Myles McDowell, “Fiction for Children and Adults: Some Essential Differences,” Writers, Critics and Children: Articles from Children’s Literature in Education, ed. Geoff Fox et al. (New York: Agathon, 1976), 141-42; Peter Hunt, Criticism, Theory, and Children’s Literature (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), particularly chapter 5, “The Text and the Reader” (81-99).

- F. J. Harvey Darton, Children’s Books in England -.five centuries of social life, 3rd ed. rev. Brian Alderson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

- Book in progress; see also my “Of Arthour and of Merlin as Medieval Children’s Literature,”Art/mr/ana 13/2 (2003): 9-22.

- Aidan Chambers/’The Reader in the Book,” Booktalk: Occasional Writing on Literature and Children (New York: Harper and Row, 1985), 34-58; here 39.

- Chambers, “The Reader,” 49-58.

- Quoted in Hunt, Criticism, Theory, and Children’s Literature, 28.

- Barbara Wall, The Narrator’s Voice: The Dilemma of of Children’s Fiction (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), 35.

- Of Arthour and Of Merlin, ed. O. D. Macrae-Gibson. EETS, 268 (London: Oxford University Press, 1973), lines 9-14.

- The Middle English Versions of Partonope of Blois, ed. A. Trampe Bödtker (London: Oxford University Press, 1912 for 1911), lines 15-22.

- The Book of the Knight of the Tower, trans. William Caxton, ed. Μ. Y. Offord. EETS, ss 2 (London: Oxford University Press, 1971).

- Mary E. Shaner, “Instruction and Delight: Medieval Romances as Children’s Literature,” Poetics Today 13 (1992): 5-15; “Sir Gowther (Advocates MS. 19.3.1)” Medieval Literature for Children, ed. Daniel Kline (New York, 2003), 299-322.

- For a critical discussion of the element of violence and alterity in this romance, see Michael Uebel, “The Foreigner Within: The Subject of Abjection in Sir Gowther” (96-117), and Jesus Montano, ‘Sir Gowther: Imagining Race in Late Medieval England” (118-32), Meeting the Foreign in the Middle Ages, ed. Albrecht Classen (New York and London: Routledge: 2002).

- Silence: A Thirteenth-Century French Romance, ed. and trans. Sarah Roche-Mahdi (East Lansing, MI: Colleagues Press, 1992).

- The Seven Sages of Rome, ed. Karl Brunner. EETS, 191 (London: Oxford University Press, 1933), 215.

- Auchinleck ends imperfect, at 2770; about 1200 lines are missing at the end, and it seems safe to assume that the storyline will not deviate significantly from other versions.

- Nodelman, Pleasures, 157.

- John Jaunzems, “Structure and Meaning in the Seven Sages of Rome,” Studies on the Seven Sages of Rome and Other Essays in Medieval Literature, ed. H. Niedzielski, H. R. Runte, and W. L. Hendrickson (Honolulu: Educational Research Associates, 1978), 43-62; here 58.

- Geoffrey Chaucer, Canterbury Tales 1.286. The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Larry D. Benson (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987).

- See Shaner, both “Instruction and Delight” and “Sir Gowther.”

- For a parallel study of a pedagogically oriented guidebook, or instructional manual, in thirteenth-century England (Walter of Bibbesworth’s Tretiz), see Karen K. Jambeck’s contribution to this volume.

- Le Mesnagierde Paris, ed. Georgina E. Brereton and Janet M. Ferrier (Paris: Livre de Poche, 1994); Janet Μ. Ferrier, “Settlement Pour Vous Endoctriner. The Author’s Use of Exempla in Le Menagier de Paris,” Medium Aevum 48 (1979): 77-89.

- Ovide Moralise, ed. Cornells de Boer et al., 5 vols. (Wiesbaden; Martin Sandig, 1966-68).

Contribution (185-201) from Childhood in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, edited by Albrecht Classen (Walter de Gruyter, 07.18.2005), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.