The party leadership felt too embattled on too many fronts to risk a split at the top.

By Dr. Neil Faulkner

Late Research Fellow

University of Bristol

The Rise of the Bureaucracy

By late 1921, almost everywhere in the world, the great revolutionary wave stirred into motion by the First World War was ebbing away. By late 1923, this was clear to all but the most die-hard optimists. Most critically, having faced down challenges from both Communist revolutionaries and Nazi counter-revolutionaries, Germany’s Weimar Republic – a liberal parliamentary regime – had achieved a measure of stability. The October Insurrection of 1917 had not ignited the world socialist revolution that the Bolsheviks had worked for. Lenin himself became a poignant symbol of the decay of revolutionary hope: increasingly incapacitated by a series of strokes, he died in 1924. The Russian Revolution was left isolated, surrounded by enemies, devastated by war, and impoverished by economic collapse. Struggling to survive in desperate conditions, the Bolshevik regime turned in on itself and, in time, morphed into a hideous mockery of its former socialist ideals.

The crisis of 1918–21 – the period of the Civil War and War Communism – transformed the character of the Bolshevik Party, the Soviets, and the Russian working class. The close political relationship between revolutionary party, democratic assembly, and industrial proletariat had made possible the October Insurrection. Trotsky used the metaphor of a steam engine: the party was the piston, in which the energy of the revolution was transmitted; the democratic assemblies were the piston box, organising and concentrating the energy; and the industrial proletariat – along with the wider Narod, the soldiers and peasants, who followed its lead – were the steam, the mass collective action which powered all the great events of 1917. This relationship broke down completely in the subsequent four years with the disintegration of Russia’s small industrial proletariat. ‘The industrial proletariat is déclassé’, Lenin declared in October 1921:

‘It has ceased to exist as a proletariat. Since the great capitalist industry is ruined and the factories immobilised, the proletariat has disappeared.’1

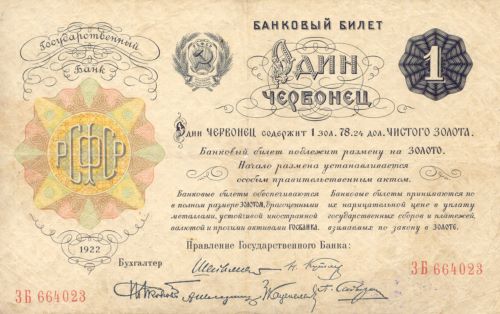

In the early 1920s, two main class forces dominated Russian life: the peasantry, now in control of the land, and the party-state bureaucracy, still infused with much revolutionary spirit, but increasingly preoccupied with the imperatives of restoring the basics of everyday life in a backward, war-ravaged, poverty-ridden economy.

The Bolshevik Party itself was transformed. Its membership swelled. The revolutionary veterans were soon swamped by post-October recruits, many joining because it was the only way to get a job and earn a living. By 1922, for example, only 15 per cent of Bolshevik Party members in Petrograd had been members in 1917; the proportion of ‘Old Bolsheviks’ – those who had been members before 1917 – was only a tiny fraction of the total.2 The latter – now usually in leading positions – enjoyed great prestige. But this did little to foster inner-party democracy. Many of the new recruits were fair-weather friends of the regime, careerists rather than idealists, happy to go with the flow, unwilling to challenge the leadership. Nonetheless, the danger was that the political pressure of this mass of new party officials, the civil servants of the Soviet regime, would undermine the revolutionary traditions of the party. The adoption of the New Economic Policy and the rise of the NEP men and the kulaks increased this danger. The conservatism of the new party bureaucracy might be reinforced by the social influence of this growing petty-bourgeois mass. They might also become transmitters into the party of the imperatives of world market competition, for the small Soviet economy, compelled to trade in order to survive, was being shaped by the international capitalist order. The Soviet state, Trotsky explained in 1927, was developing

directly or indirectly, under the relative control of the world market. Herein lies the root of the question. The rate of development is not an arbitrary one – it is determined by the whole of world development, because in the last analysis world industry controls every one of its parts, even if that part is under the proletarian dictatorship and is building up socialist industry.3

Lenin spelt out the implications: ‘The proletarian policy of the party is not determined by the character of the membership,’ Lenin observed, ‘but by the undivided prestige enjoyed by the small group that might be called the Old Guard of the party.’ But in the growing social vacuum in which it operated, that ‘Old Guard’ felt compelled to shore up its defences: the Tenth Party Congress of March 1921 voted to ban internal factions – a major restriction on inner-party debate and democracy. This was one measure of the desperation with which the Bolshevik leadership acted to preserve the revolutionary tradition and maintain the Soviet regime as an outpost of socialist revolution pending the next global upsurge. But they were fighting a tragic battle against history. Beneath their feet was shifting sand. ‘Permit me to congratulate you on being the vanguard of a non-existent class’ was the bitter reproach addressed to Lenin by one revolutionary veteran.4

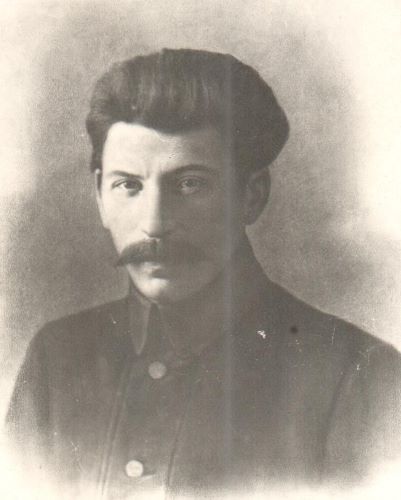

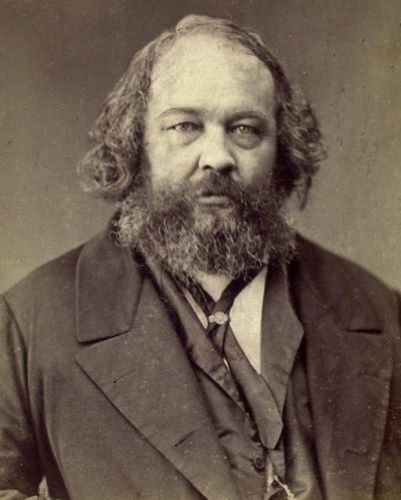

At the end of his life, increasingly incapacitated by strokes, Lenin became preoccupied with the problem of bureaucratic degeneration. Sensing that his life’s work was slipping away, he waged his ‘last struggle’ – against Joseph Stalin and the emerging party-state bureaucracy. In a secret ‘Testament’ written shortly before his death, he warned leading party comrades that the Secretary-General of the Party had ‘unlimited authority concentrated in his hands’, that he was ‘too rude’, and that they should therefore

think about a way of removing Stalin from that post and appointing another man in his stead who in all other respects differs from Comrade Stalin in having only one advantage, namely, that of being more tolerant, more loyal, more polite, and more considerate to comrades, less capricious, etc.5

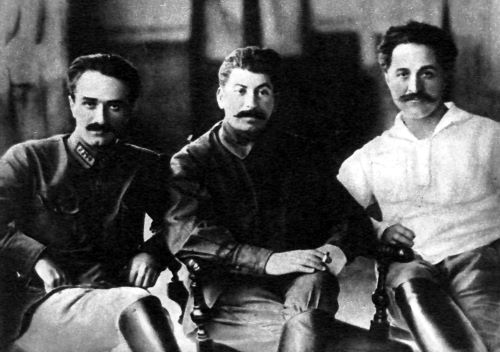

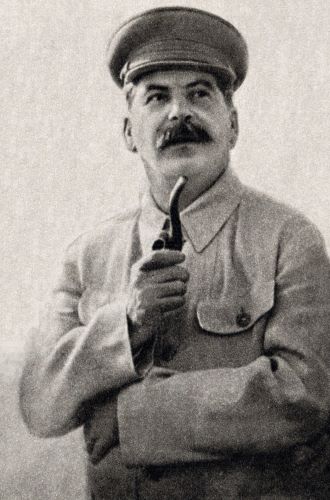

It was not to be. The party leadership felt too embattled on too many fronts to risk a split at the top. Lenin’s prescription was, in any case, no remedy for the disease. Seeing no other way out, he had been reduced to proposing that the Bolshevik Revolution be rescued by a mere shuffling of its high command. The fundamental problem was not that Stalin was a boorish bureaucrat. It was that the political leadership of the emerging party-state apparatus required a boorish bureaucrat. The man whom Sukhanov remembered as ‘a grey blur’ in the great events of 1917 – a backroom operator, a party hack, not a mass leader, not an orator, writer, or theoretician – had now come into his own. And as Secretary-General of the Party, in the new world coming into being – a bureaucratic dystopia more in keeping with a Kafka novel than a Marxist tract – he held the prime position, in control of appointments to every section of the party-state apparatus. Within a year of his taking up post, and even before Lenin’s death, 10,000 new assignments had been made. The burgeoning bureaucracy – increasingly formed of men and women who owed their position to Stalin’s faction – now dominated party congresses. More than half the delegates at the Twelfth Party Congress in April 1923 were party officials. A year later, at the Thirteenth Party Congress in May 1924, it was two-thirds. This was a critical turning point.

Not a single member of the internal party opposition was elected as a voting delegate to the Thirteenth Congress. Delegates were now chosen by processes of co-option and selection from above. Dissent and debate were minimal. Party democracy had been hollowed out. Nikolai Bukharin described how it worked in the Moscow party in late 1924:

the secretaries of the party cells are usually appointed by the district committee … Normally the putting of the question to a vote takes place in a set pattern. They come and ask the meeting ‘Who is against?’, and since people more or less fear to speak out against, the individual in question finds himself elected secretary of the bureau of the cell … The same thing can be observed in a somewhat modified form in all other stages of the party hierarchy as well.6

The takeover by the party bureaucracy was given clear political expression by the adoption, at the Fourteenth Party Congress in December 1925, of the doctrine of ‘socialism in one country’. This amounted to the evisceration of the entire Marxist tradition – which can be defined as the theory and practice of international proletarian revolution – and of the Bolshevik tradition, which, true to Marxism, had insisted time and again that Russia was merely a link in a global chain, the 1917 revolution but a stage in a process, the Soviet regime dependent for its long-term survival on a new upsurge of revolutionary struggle on a worldwide scale.

But this perspective did not reflect the interests of the party-state bureaucracy. They were administrators involved in economic modernisation and social reconstruction; essentially, they were technocrats with a practical job of work to do. Increasingly, they were conscious of themselves as a group with common interests and shared goals; a group, indeed, that now formed the leadership of Soviet Russia. They were, according to Stalin, ‘an order of Teutonic knights at the centre of the Soviet state’. More than that: as Christian Rakovsky and a group of Russian oppositionists observed in 1930, they were an embryonic ruling class:

Before our very eyes, there has been and is being formed a large class of rulers with their own subdivisions, growing through controlled co-option … What unites this peculiar sort of class is the peculiar sort of property, namely, state power … [The bureaucracy] is the nucleus of a class … Its appearance will mean that the working class will become another oppressed class. The bureaucracy is the nucleus of some kind of capitalist class, controlling the state and collectively owning the means of production.7

‘Socialism in one country’ (or ‘national socialism’) is a contradiction in terms. There is worldwide socialist revolution and there is the international capitalist system; there is no ‘middle way’, merely moments in a process of transition towards one or the other. Soviet Russia was metamorphosing into a form of what is best described as ‘state-capitalism’. It was – as some oppositionists expressed it at the time of the Fourteenth Congress – becoming a ‘radish’: red on the outside, white on the inside. Between 1923/4 and 1928/9 – that is, between Lenin’s death and the termination of the New Economic Policy – that process of transformation accelerated dramatically. The party expanded from half a million members to a million and a half. By the end of the decade, two-thirds of members had joined during the NEP years, most of them after Lenin’s death. Lenin became a cult figure, his body mummified and put on display, his ideas turned into a catechism to be learned like religious dogma, with Stalin’s dismal Foundations of Leninism as its missal.8

The destruction of opposition currents inside the party was easily accomplished. Though the highest levels of the state were convulsed by arguments around four critical issues – the growth of bureaucracy, the relations between town and country, the speed of economic development, and ‘socialism in one country’ versus international revolution – Stalin’s Centre faction, resting on the support of the party-state apparatus it had itself created, remained predominant throughout. Successive oppositions were disoriented by an historical process they did not fully understand; but more importantly, they were disabled by their isolation inside the party machine, while being unable – and to some degree unwilling – to build a political base outside it.

At first, Zinoviev and Kamenev formed a ‘Troika’ with Stalin against Trotsky’s ‘Left Opposition’ (1922–5). Then, awakening to the danger represented by Stalin, they broke with him to form a ‘United Opposition’ in alliance with Trotsky (1925–7). Finally, with the United Opposition defeated, the alliance between Bukharin and Stalin disintegrated (1927–8), bringing the process of bureaucratic degeneration to its second great turning point – the moment when a new ruling class emerged fully fledged and took wing. ‘Socialism in one country’ now culminated in an all-out attempt to build a new state-capitalist economy based on the forced collectivisation of agriculture, intensified exploitation and capital accumulation, and state-driven investment in heavy industry and arms production. This, however, required the final destruction of what remained of Lenin’s Bolshevik Party and the Russian revolutionary tradition.

The party-state bureaucracy that had emerged in Russia under Stalin’s leadership was, by 1928, strong enough to complete what was, in effect, a counter-revolution. It had been accumulating power for a decade, and when it moved decisively at the end of the 1920s, it was able to destroy all remaining vestiges of working-class democracy. Meetings were packed, speakers shouted down, oppositionists purged and deported by an apparatus now dominated by officials who had joined it since the revolution.

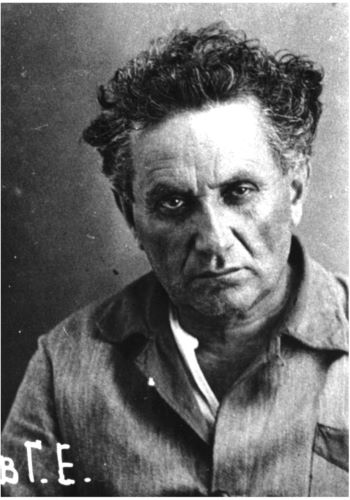

During the 1930s, the bureaucracy consolidated its grip by liquidating virtually the whole of the old Bolshevik Party. Veterans of the October Insurrection were arrested, tortured, paraded in show trials, denounced as ‘saboteurs’ and ‘wreckers’, and then executed by Stalin’s secret police. Against Trotsky and the tiny numbers of brave men and women who stood with him to the end was the power of inertia in an exhausted, impoverished, peasant country. Without world revolution to reinforce them, backward war-torn Russia had simply consumed its native revolutionaries – until they were so few that they could be swept into the oblivion of the Gulags.

Even so, the idealism and experience of the revolutionary years survived in popular memory and served to indict all that followed. For this reason, the remaining revolutionaries were hounded to their deaths during the 1930s. Only one in 14 of the Bolshevik Party’s 1917 members still belonged to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1939; virtually all of the rest were dead. Of the nine members of Lenin’s last Politburo (in 1923), only two were still alive at the end of 1940 (Stalin and Molotov). Of the others, one died of natural causes (Lenin), one committed suicide in fear of arrest (Tomsky), and the remaining five were murdered (Kamenev, Zinoviev, Bukharin, Rykov, and Trotsky).

State-Capitalism in Russia

The bureaucracy acted in 1928 because it had the power to do so and because it faced a crisis. The peasants were refusing to supply enough grain to the cities, and foreign governments were cutting off diplomatic relations and banning trade links. There was growing fear of war. The Russian state was no longer the centre of world revolution it had been in 1921. It was again, as it had been under the Tsars, one of Europe’s great powers. Its defence was no longer seen to be a matter of proclamations and proletarian solidarity, but of tanks and heavy artillery. The leadership’s response to the crisis of 1928/9 was to seize the grain, drive down wages, and impose rapid industrialisation. The Russian dictator explained the logic: ‘To slacken the pace of industrialisation would mean to lag behind, and those who lag behind are beaten … We are 50 to 100 years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this lag in ten years or they will crush us.’9

Russia had survived civil war and foreign invasion: the new regime had not been destroyed by military force. But the defeat of the world revolution had left Russia isolated and impoverished in a global economy dominated by capitalism. So the counter-revolution was achieved not by violent overthrow, but by the relentless external pressure of economic and military competition. Russia needed to export grain to pay for machine tools. It needed machine tools to build modern industries. It needed these to produce the guns, tanks, and planes with which to defend itself in a predatory global system of competing nation-states. Private capital accumulation was too slow. What Bukharin in the 1920s had called ‘socialism at a snail’s pace’ would have left Russia trailing behind and ever vulnerable to dismemberment by hostile powers. Only the state had the power to concentrate resources, impose a plan, override opposition, and drive through rapid forced industrialisation. The aim was mass production to build state power. Russia’s rulers thus became personifications of state-capitalist accumulation. But they also used their power to reward themselves richly, even as they plundered the peasantry, cut wages, increased work pressure, and filled the Gulags with slave-labourers.

By 1937, plant directors were paid 2,000 roubles a month, skilled workers 200–300 roubles, and workers on the minimum wage 110–115 roubles. Pay differentials in the army were even more extreme: during the Second World War, colonels were paid 2,400 roubles a month, private soldiers 10. The pay of plant directors and army colonels was modest, however, compared with that of top members of the state bourgeoisie earning up to 25,000 roubles a month – more than 200 times the minimum wage. So the bureaucracy had become a privileged class with a clear material interest in remaining loyal to Stalin and the state-capitalist system. It therefore proved utterly ruthless in imposing forced industrialisation on society at a colossal cost in human suffering.

Consumption was sacrificed to investment in heavy industry. The proportion of investment devoted to plant, machinery, and raw materials – as opposed to consumer goods – rose from 33 per cent in 1927/8 to 53 per cent by 1932 and 69 per cent by 1950. The result was shortages and queues – though less than there might have been, because wages were cut at the same time, by an estimated 50 per cent over six years. Grain was seized from the peasantry to feed the growing urban population and to pay for imports of foreign machinery. Because of this, when the price collapsed on world markets in 1929, at least three million peasants starved to death. It was not enough. The state decreed ‘the collectivisation of agriculture’ (state control). Millions of peasants – denounced as kulaks (rich peasants producing for the market) – were dispossessed and transported. Many died. Others ended up as slave-labourers in the Gulags, which expanded into a vast Siberian slave empire run by Stalin’s security apparatus. The 30,000 prisoners of 1928 had become two million by 1931, five million by 1935, and probably more than ten million by the end of the decade. Millions of others were simply murdered by the police, the annual cull rising from 20,000 in 1930 to 350,000 in 1937. State terror on this scale reflected Russian backwardness, the pace of state-capitalist accumulation, and the levels of exploitation necessary to achieve it. The working class, the peasantry, and the national minorities had to be pulverised into submission.10

The damage was not confined to Russia. The revolutionary content of Marxism was abandoned but its verbal formulas were retained and redeployed to justify the policies of the Russian bureaucracy. The Comintern – the Communist International – became a vehicle for imposing the ideology and policies of the Russian state on foreign Communist parties. In 1927, having abandoned world revolution in favour of ‘socialism in one country’, Stalin tried to break out of Russia’s isolation by seeking respectable allies abroad. So the Chinese Communist Party was ordered to kow-tow to Chiang Kai-shek and disarm the Shanghai working class. The result was a terrible counter-revolutionary massacre. The following year, the policy suddenly switched to sectarianism and adventurism. In the Comintern’s disastrous ‘Third Period’, Stalin proclaimed a new revolutionary advance, such that Communists were to break all ties with Social Democrats and prepare for an imminent seizure of power.

This mirrored (and helped justify) the policy inside Russia. The attack on the kulaks was presented as an attack on private capitalism (which was true) and as a major advance towards ‘socialism’ (which was not). The ultra-left turn of the Third Period provided a smokescreen for bureaucratic power and forced industrialisation. The sectarianism of the Third Period created a fatal division inside the German labour movement and allowed Hitler to take power in 1933.

But the Nazis threatened a resurgence of aggressive German imperialism, and Stalin began casting around for European allies. The Comintern therefore lurched from ultra-left madness to ‘Popular Frontism’: Communists were now to form alliances with the liberal bourgeoisie, reining back the working class to placate potential allies of the Russian state.

Thus, instead of promoting world revolution, the Stalinist Comintern had, by the mid 1930s, become actively counter-revolutionary. This was to produce, in 1937, another catastrophic disaster to place alongside those of 1927 and 1933, when the Spanish Communist Party, under orders from Moscow, spearheaded the suppression of the working-class revolt in Catalonia, decapitating the entire revolutionary movement inside the Spanish Republic and derailing the struggle against Franco’s fascists. The Spanish workers would pay a terrible price: 40 years of right-wing dictatorship.

With the triumph of Stalin in Russia in 1928 and of Hitler in Germany in 1933 a terrible darkness descended on Europe. The continent became a place of dictatorship, persecution, and militarism. Later it would explode into war – the most terrible war in history, one in which 60 million would die, most of them in mass campaigns of genocide and ethnic-cleansing. The horrors of Stalingrad, Auschwitz, and the Gulags were the bitter fruit of revolutionary defeat, counter-revolutionary triumph, and a world gone mad. They were the historic confirmation of the chilling prediction made long before by the German-Polish revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg that humanity faced a choice between socialism and barbarism. We face it still.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 11 (237-) from A People’s History of the Russian Revolution, by Neil Faulkner (Pluto Press, 03.15.2017), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.