By Mark Cartwright

Historian

Introduction

One of the major motivating factors in the European Age of Exploration was the search for direct access to the highly lucrative Eastern spice trade. In the 15th century, spices came to Europe via the Middle East land and sea routes, and spices were in huge demand both for food dishes and for use in medicines. The problem was how to access this market by sea. Accordingly, explorers like Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) and Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) were sent to find a maritime route from Europe to Asia. To the west, Columbus found a new continent in his way, but to the south, da Gama did round the Cape of Good Hope, sail up the coast of East Africa, and cross the Indian Ocean to reach India. From 1500 onwards, first Portugal, and then other European powers, attempted to control the spice trade, the ports which marketed spices, and eventually the territories which grew them.

The Spice of Life

In the medieval and early modern periods, ‘spice’ was a term liberally applied to all kinds of exotic natural products from pepper to sugar, herbs to animal secretions. Spices had been imported from the East into Europe since antiquity, and Europeans had developed a definite liking for them. Part of the attraction was the flavour they gave dishes, although the long-held view they were primarily used to disguise the taste of bad meat is incorrect. Another attraction was their very rarity, making them a fashionable addition to any table and a real status symbol for the wealthy. Spices were used to add flavour not only to sauces but also wines; they were even crystallised and eaten on their own as sweets.

Valuable spices used in food preparation across Europe included pepper, ginger, cloves, nutmeg, mace, cinnamon, saffron, anise, zedoary, cumin, and cloves. Although most of these were reserved for the tables of the rich, even the poorer classes used pepper whenever they could get it. Spices, despite their cost, were used in great quantities. Sacks of spices were required for royal banquets and weddings, and we know, for example, that in the 15th century, the household of the Duke of Buckingham in England went through two pounds (900 grammes) of spice every day, mostly pepper and ginger.

Spices had other uses besides their flavour. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, it was believed that many spices had medicinal value. Firstly, they could be used to purge the body. Secondly, the idea that a healthy body required a balance of its four core elements or humours was still prevalent. A healthy diet, therefore, also needed to balance these humours, that is, one’s food should not be too hot or cold, dry or moist. Spices helped put certain foodstuffs into balance. Fish, for example, was a cold and wet food and so by adding certain spices to fish dishes, these two characteristics became more balanced.

Spices were burned like incense for their perfume or scattered on floors or even added directly to the skin. Everywhere from churches to brothels used spices to improve the generally bad odour of the medieval indoors. The most sought-after and expensive perfumes were frankincense, myrrh, balsam, sandalwood, and mastic. There was another group of scents that came from animals which were equally prized. These included secretions from wild cats (civet), beavers (castoreum), and deer (musk). A third category of aromatic spices was those substances scraped off ancient mummies and other weird exotica.

Spices could also be taken as medicines in their own right and so were crushed and made into pills, creams, and syrups. Black pepper was considered a good treatment for coughs and asthma, it could, the chemists claimed, heal superficial skin wounds and even act as an antidote to some poisons. Cinnamon was thought to help cure fevers, nutmeg was good for flatulence, and warmed ginger was considered an aphrodisiac. Several strong-scented spices were thought capable of combatting foul smells, which themselves were thought to cause diseases. For this reason, during the many waves of the Black Death plague that swept across Europe, people burnt ambergris to ward off the often fatal disease. Ambergris was a fatty substance, which came from the inside of whale intestines. Gemstones and semi-precious stones, also being rare and difficult to get hold of, were often categorised as spices. Certain stones like topaz were thought to ease haemorrhoids, lapis lazuli was good for malaria, and powdered pearls, mixed with as many expensive spices as possible, were taken to prevent old age.

The Search for Spices

There were some voices of protest at these beliefs by some medical practitioners, and some members of the Church were often outspoken in their belief that all this money spent on spices could be better used elsewhere. Nevertheless, with all of these possible uses and their status as the must-have luxury good, it is no wonder that some of Europe’s elite began to ponder how they could get direct access to the spices of the East without paying through the nose to Eastern and Arab merchants. Where these merchants themselves got their spices from was not certain. Many tall tales developed as to the origins of spices, but by the 13th century, travellers like Marco Polo (1254-1324 CE) and missionaries were beginning to improve Europe’s geographical knowledge of the wider world. India seemed awash with black pepper. Sri Lanka was rich in cinnamon. Sandalwood came from Timor. China and Japan were getting spices like cloves, nutmeg, and mace from India, South East Asia, and the Maluku Islands or the Moluccas in what is today Indonesia – not for nothing were they nicknamed the Spice Islands.

Then, in 1453 came the fall of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, and so one of the principal land routes for spices into Europe was lost. This was one more reason for European merchants to find their own access to the spice trade routes and, if possible, achieve control of their production at the source. European powers like Spain and Portugal might also be able to deal a severe blow against their rivals in Europe, particularly the Italian maritime states like Venice and Genoa. There was the added bonus, too, that by circumventing the Islamic traders who dominated the trade in the spice markets of Aden and Alexandria, Christendom would not have to give its gold to its number one ideological enemy. There might even be Christian allies in Asia who were as yet unknown to Europe.

More practically, discovering new agricultural land to grow cereal crops would help reduce trade deficits. There was, too, the real prospect of acquiring prestige and riches for the European elite and those mariners who dared sail into the unknown. Finally, the feudal system in Europe was degenerating as land was parcelled out in ever-smaller pieces to generation after generation of sons. Many lords simply did not know what to do with their third or fourths sons and sending them to foreign lands to make their fortune was a happy solution for both parties.

There were then, economic, political, and religious motives for finding a sea route from Europe to Asia. With backing from the Crown and Church, as well as private investors who dreamed of huge returns, explorers set sail for unknown horizons.

A Maritime Route to Asia

The Eastern spice trade had been going on since antiquity. Prior to the 16th century, spices came over land and sea routes from the East, up the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, across Egypt or Arabia, and into the Mediterranean. The Silk Routes from China through Eurasia was another way spices entered into European markets. As the historian M.N. Pearson summarises, the costs required to get spices to Europe using the traditional Middle East routes were very high indeed:

…the price of a kilo of pepper as it changed hands was enormous – costing 1 or 2 grammes of silver at the production point, it was 10 to 14 in Alexandria, 14 to 18 in Venice, and 20 to 30 in the consumer countries of Europe. (41)

Riches could be won, then, if the Europeans could bypass the established routes and meet the ever-rising demand for spices in Europe. In order to achieve this, a maritime route to Asia had to be found.

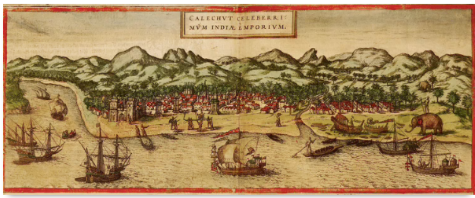

In 1492, Christopher Columbus thought he could find it by sailing west across the Atlantic Ocean but he only succeeded in finding another landmass in his way: the Americas. The Portuguese believed they could find Asia by sailing around the African continent. In 1488 Bartolomeu Dias sailed down the coast of West Africa and made the first voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, the southern tip of the African continent (now South Africa). He was followed by Vasco da Gama who, in 1497-9, also rounded the Cape but then sailed on up the coast of East Africa and crossed the Indian ocean to reach Calicut (now Kozhikode) on the Malabar Coast of southern India. Finally, the Europeans had found a direct maritime route to the riches of the East. From the Malabar Coast of India, European ships could then sail further East to the Spice Islands and South East Asia. A route was opened up by Francisco Serrão, who sailed to the Spice Islands in 1512, and Ferdinand Magellan (1480-1521) when he made the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1519-22 in the service of Spain.

Portuguese Colonization

Getting geographical access to the spice trade was one thing, muscling in on the trade itself was quite another. The first and biggest problem for the Portuguese in their trading ambitions in the East was that they did not really possess any goods the Indian or Muslim traders desired. Many rulers were already immensely rich, and they were loath to make any changes to a regional trade network that was working extremely well and, more importantly for everyone, peacefully. The Portuguese decided to use the one thing they had in their favour: superiority in weapons and ships. Indian rulers and some Arab traders did have some cannons, but these were not of the same quality as the European ones, and more significantly, trade ships in the Indian Ocean were built for cargo and speed, not for naval warfare. The Europeans, in contrast, had been fighting sea battles for some time.

The solution was simple, then: take over the trade network by force and establish a monopoly on the spice trade not only in terms of Asia with Europe but also within Asia, too. Spices could be acquired from spice growers as cheaply as possible for relatively low-value goods like cotton cloth, dry foodstuffs, and copper, and then sold in Europe for as much as possible. Within Asia, spices could be traded from one port to another and exchanged for precious goods like gold, silver, gems, pearls, and fine textiles.

Accordingly, more and more warships were sent around the Cape of Good Hope, and forts were built everywhere, starting with Portuguese Cochin (Kochi) in India in 1503 and eventually spreading to Japan. Rival ships were blasted out of the water and uncooperative towns were given a barrage of broadsides. Goods were confiscated and traders pressured into favourable deals. Undeterred by the immensity of the geographical area the Portuguese would have to patrol, King Manuel I of Portugal (r. 1495-1521) declared a royal monopoly on the spice trade. A viceroy of India was appointed in 1505, even though the Portuguese had no real territorial aims beyond controlling coastal trading centres. Portuguese Goa was established in 1510 on the west coast of India, and within 20 years it became the capital of Portuguese India. In 1511 Malacca in Malaysia was taken over. Hormuz at the mouth of the Persian Gulf followed in 1515, and a fort was established at Colombo in Sri Lanka in 1518.

The Royal Monopoly

Enforcing a monopoly on the spice trade across one-third of the globe was practically impossible but the Portuguese had a very good stab at it. Besides the use of cannons as mentioned earlier, administrative controls were put in place. First, any private trader – European or otherwise – caught with a cargo of spices was arrested, his wares and ship confiscated. Muslim traders fared the worst and were often executed. After it was realised this policy was impossible to enforce everywhere, some local traders were permitted to trade spices in limited quantities, but often only one, most commonly pepper. Crews of European ships were permitted to take quantities of spices as a substitute for pay (a small sackful could buy them a house back home).

Another way to control the spice trade, and that in other goods, was to only permit ships to visit certain ports if they had a royal license. In short, the seas were no longer free. Even ships trading goods other than spices had to travel with a Portuguese-issued passport or cartaz, and if they did not, the cargo and ship were confiscated and the crew imprisoned or worse. In addition to the cartaz, ships had to pay customs duties at their port of call. Yet another method to extract duties was to oblige all ships to sail in Portuguese-protected convoys, the cafilas. Pirates were a threat in the Indian Ocean and beyond, but the real purpose was to ensure all trading ships stopped at a Portuguese-controlled port where they would have to pay duties (plus leave a cash deposit guaranteeing they returned to make a second payment).

In these various ways, customs duties came to account for some 60% of the entire Portuguese revenue in the East. In addition, profits were, just as had been hoped, made from the spices themselves. The Portuguese could now buy the spices at the source. For example, one quintal (100 kg/220 lbs) of pepper could be bought for 6 cruzados (a gold coin of the period) and sold in Europe for at least 20 cruzados. There were transport costs and the expense of maintaining patrol ships and forts but, all in all, the Portuguese could make a very handsome 90% profit on their investment. Further, the more spices that were imported, the lower the overall costs. The Portuguese desire to buy and control spices became insatiable.

The attempt to control the spice trade had other consequences besides those already mentioned. The trade network was shifted to new areas so that some established centres like Cochin went into decline and others like Goa rose. Missionaries spread the Christian faith. Plants and animals were introduced to new places, often causing unforeseen repercussions in habitat and upsetting the balance of local ecological systems. Diseases spread in all directions to find new victims.

The Opening Up of Asia

The Portuguese had more or less established a monopoly on the spice trade in Europe, but their dominance in Asia was short-lived. Asian merchants avoided the Europeans whenever possible and carried on with their duty-free trade. It is important to note that Europe accounted for only around one-quarter of the global trade in spices. Many Portuguese officials were themselves corrupt and traded without paying the Crown its slice of income. The Middle East land and sea routes to transport spices, never entirely replaced by the Cape of Good Hope route, began to prosper again in the second half of the 16th century thanks to the ever-increasing demand for spices in Europe.

Other European nations soon got wind of the riches available to those with direct access to the spices. Between 1577 and 1580, the Englishman Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE) made his circumnavigation of the world which included a stop off at the Spice Islands to take a cargo of cloves. The first to really challenge the Portuguese, though, were the Dutch who, from 1596, had no qualms about attacking forts at Portuguese centres, which were poorly garrisoned and which often suffered from a lack of upkeep. The territories involved were so large, that the Portuguese could not patrol even a small fraction of them. The Dutch took direct control of the Spice Islands and captured Malacca (1641), Colombo (1656), and Cochin (1663). By controlling the source of the spices, the Dutch could now impose their own terms on the global spice trade and import to Europe three times the quantities of spices the Portuguese could transport. Meanwhile, the Persians, with English assistance, took over Hormuz in 1622. The Hindu Marathas were winning great victories in southern India and threatening Portuguese centres there. The Gujarati traders were dominating the Bay of Bengal trade. In short, everybody loved spices and the wealth they brought.

Even more significantly, the European nations were now adapting their foreign policies. It was no longer a case of exploration and discovery to establish a handful of coastal trade centres. Colonization was now about holding territory, conquering indigenous peoples, and resettling Europeans. Trading companies were set up by the Dutch and English which allowed for much more efficient acquisition and distribution of goods. Sugar cane, cotton, tea, opium, gold, diamonds, and slaves would take the place of spices in the world economy as the European powers raced to carve up the world and build an empire. The drive to control the spice trade, then, had opened up the world, but it was to become a much more violent and unstable one in the centuries to follow.

Bibliography

- Bergreen, Laurence. Over the Edge of the World Updated Edition. William Morrow Paperbacks, 2019.

- Cliff, Nigel. The Last Crusade. Harper Perennial, 2012.

- Disney, A. R. A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire, Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Disney, A. R. A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire, Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Pearson, M. N. NCHI. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Russell-Wood, A. J.R. The Portuguese Empire, 1415-1808. JHUP, 1998.

Originally published by the World History Encyclopedia, 06.09.2021, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.