The utility designs constituted a separate system of intellectual property.

By Olivia Gecseg

Visual Collections Records Specialist

The National Archives, UK

Introduction

The Victorian era was an amazing time for inventive activity. Advances in technology, science and industry brought change to all areas. One setting that provided endless inspiration for Victorian inventors was their homes. As it took on new forms and functions in the wake of rapid social change, the Victorian home sparked ideas for an array of creative inventions attempting to improve the domestic experience.

The 1800s saw inventions such as the lightbulb, the telephone and the sewing machine enter the home. These would gradually make significant changes to the way people lived. At the same time, there were many more new designs for cutlery, coffee makers, chairs and candles that also contributed to the increased comfort, efficiency, and safety felt by Victorians at home.

While they are often confused with patents of invention, the utility designs constituted a separate system of intellectual property, that operated alongside the pre-existing patent system in Britain from 1843–1883. As opposed to patents, registered designs rarely represent the first version of a technology but rather a new version or configuration of an existing technology. They also represent more everyday types of objects, such as kettles or mouse traps. Finally, because there was no obligation to bring them to market, they can often depict rather eccentric solutions.

Waking Up on Time

Towns and cities grew exponentially in the 19th century. By 1851, half of Britain’s population lived in London. An urban lifestyle made timekeeping a more common concern, although few had access to a personal alarm clock and were woken up by the local knocker-upper, a person employed to bang on doors and windows in the morning.

This clever, albeit somewhat hazardous-looking, invention is for an alarm clock designed to wake someone up to a pot of hot water, making it an early forerunner of the 20th-century Teasmade design.

It operated by lighting a candle that was set up next to a scale marking out the hours. The candle had a thread passed through the wax at a point that corresponded to the hour the person wanted to be woken up at. When the candle eventually burned down, the broken thread disengaged a bell, making it ‘ring violently’ and ‘awaking the person desiring to be called’.

The candle had meanwhile been heating water in a copper pot sat on a metal plate fixed above the flame. The candle would continue to burn while the water was being used and eventually broke another thread that released a cap to extinguish the candle.

It took another forty years at least for a similar invention to have more success (see footnote 1). One reason for this may have been that whoever used the alarm had to be comfortable sleeping near to an open flame and a balancing pot of boiling water.

Fleeing Danger

There were no shortages of hazards in the Victorian home and the risk of fire was particularly grave. It was heightened by the uptake of a new assortment of household appliances like kitchen ranges, boilers, and gas lamps, contributing to a surge in domestic fires (see footnote 2). There was also no public fire service until the Metropolitan Fire Brigade in 1866, which only operated in London. Prior to this, fire brigades took the form of various professional and volunteer services, sometimes operated by insurance companies.

Lack of regulations in fire safety resulted in a strange assortment of designs to help people escape a burning building. One came in form of a chute, constructed from cloth sewn together to make a tube. It could be hooked onto a window frame to allow someone to slide down to the ground in safety. This design from 1845 had added loops at the bottom so bystanders could hold it steady as the person descended. Interestingly, this is a design concept still in use today.

Malodorous Lavatories

Despite the popular narrative, Thomas Crapper was not the inventor of the flushing toilet – and by quite a long way. The mechanics of the flush have been around since at least 1596, when Sir John Harrington sought to install one for a visit from his godmother, Queen Elizabeth I. The lack of indoor plumbing meant that the design failed to interest engineers further until the late 1700s.

Thomas Crapper was just one of many nineteenth-century engineers (albeit with slightly better marketing) who attempted to improve the design, like Charles Chapman Clark, who registered a design for a self-acting water closet in 1849.

Clark’s design is interesting as the description and the drawings shows his flush was operated through the seat. When someone sat down, the pressure on the front of the seat opened a valve and caused the cistern to fill with water. When they stood up, the valve at the bottom of the cistern was opened and released the water to flush the toilet or trap out through the ‘service pipe’.

But why were so many inventors struggling to improve the loo? Flushing toilets in use at the time were smelly and unhygienic. The title of an earlier design registered by Clark is more explicit in its intent: ‘a self-acting valve to prevent the escape of effluvia from drains’ (BT 45/6/1057). An increasing awareness of the links between deadly disease and unsanitary conditions, plus the contemporary belief that diseases like cholera were airborne, triggered a drive to invent a solution in the form of a water closet or ‘stink trap’.

The other issue was with the wider sanitation system. Before Joseph Bazalgette’s amazing feat of Victorian engineering, there was no sewage system in London. Toilets were being emptied into the same water system used for drinking and washing, causing awful cholera outbreaks. The vast amount of waste that ended up in the Thames led to the Great Stink of 1858, prompting serious action to be taken by government.

Pest Control

Victorians also struggled to keep pests out of homes and gardens, as these inventions show.

These glass bubbles were the brainchild of a professional gardener, designed to to be fastened over fruit growing against a wall or other flat surface with a wire. When the record provides the occupation of the inventor, we can often see how their professional expertise fed into their design. In this case, we can also perceive a gardener’s frustration at fruit being persistently eaten by insects or birds!

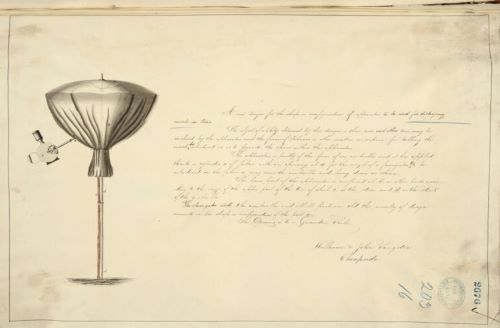

In the case of this invention for controlling garden pests however, the inventors were not horticulturalists but rather celebrated umbrella manufacturers and entrepreneurs, William and John Sangster. They used the umbrella as the basis for a cover for a tree. The umbrella ribs held up a piece of fabric that hung like a veil over the tree and was wrapped around the truck to enclose its branches. The fabric had a hole which a nozzle of a fumigator could be inserted to pump in tobacco fumes, a natural pesticide.

The Sangsters registered many other novel umbrella designs but this appears to have been their only attempt to break into the gardening tool market.

Endnotes

- ‘Teasmades: From Clockwork Cuppas to the Smart Home’, Science Museum https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/everyday-wonders/teasmade-smart-home

- Julie Halls, Inventions that Didn’t Change the World (Thames and Hudson, 2014)

Originally published by The UK National Archives, 12.20.2022, under Crown CopyrightOpen Government Licensing.