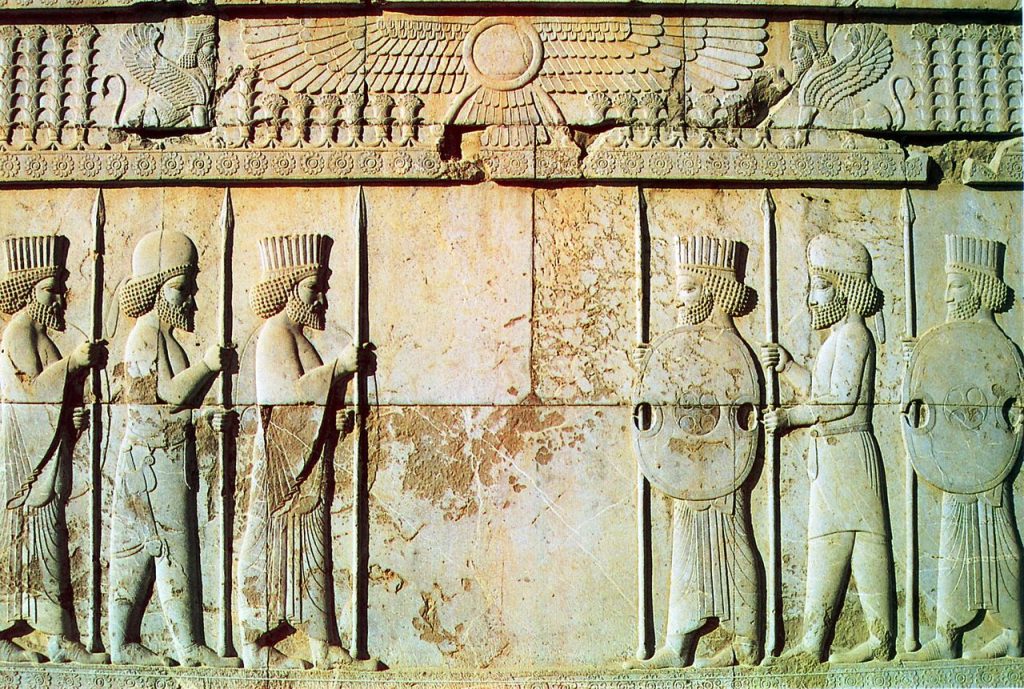

The Persian Army became a multi-cultural force consisting of a fusion of soldiers from Persia or the Medes, as well as various warriors from all subject nations.

By Michelle Chua

Introduction

No ruler can expand his territory without an army. The massive Persian army, reported by Greek historian, Herotodus, to be about 2,641,610 warriors strong[1] during the invasion of Greece by Persian king, Xerxes I, and played a significant role in the rapid expansion of the Persian Archaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE), which at the height of its power spanned three continents: Asia, Africa and Europe.

By 480 BCE, the empire accounted for approximately 49.4 million of the world’s 112.4 million people – equivalent to 44% of the world’s entire population!

Persian king Darius I was extremely tolerant of the different cultural and religious pursuits that were practiced within his empire. His inclusion of various cultures was especially apparent in the complexity of the Persian army. The ethnic diversity of its soldiers and variety of weaponry, as a result of the incorporation of warriors from subject nations and employment of mercenaries, was pivotal in the development of each warrior class’ military strategy and weaponry, which ultimately contributed to the successful expansion of the Achaemenid Empire.

Ethnic Diversity of the Persian Army

Incorporation Of “Fringe” Territories

With the expansion of the kingdom of Persia into the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian army soon became a multi-cultural force consisting of a fusion of soldiers from Persia or the Medes, as well as various warriors from all subject nations.

Based on official Persian economic and military documents, Herodotus claimed that the closer a subject nation was to Persia, the more it shared in the domination of the empire by paying lesser tribute but contributing more soldiers. Thus, the Medes who had the second position in the empire furnished more soldiers than other nations, while many of the imperial generals were chosen from the Medes. Then came the Sakas (Scythians), Hycarnians, Bactrians, Egyptians, Ethiopians, Indians, and lesser known factions, like the Sagartians who were Iranian nomads that fought as cavalrymen with lassos and battle-axes.

This continuous incorporation of soldiers from conquered territories additionally brought forth unique military ideas that were quickly adopted by the Persians. Weaponry from both the Saka tribes and Indians, such as their archery bows and war elephants respectively, were soon prevalent in the conquest of expanding Persia.

Dependence on Mercenaries

According to Histories by Herodotus, conscription of foreign mercenaries began during the reigns of Cyrus the Great and Cambyses II when the Persian army mainly employed subject and mercenary Greeks from the Ionian and Aeolian tribes. By the time of king Darius I, dependence on foreign mercenaries became a centralized system, employing mercenaries even in the ranks of elite forces or the king’s personal bodyguards.

Ironically, despite the immense feud between the two countries (do read the blog post The Greco-Persian War, Greece itself was the greatest source of mercenaries for the Persian empire.

During Xerxes I’s invasion of Greece, he realized that the ill-supplied Persian infantry’s lack of armor and light shields fared poorly against the Greek’s advanced armor and weaponry.[2] As cited by consultant Alan Axelrod in Mercenaries , Greek mercenaries were also known to be loyal to the people who hired them. Moreover, as the Greeks treated war as part of their lives, they were excellent, undaunted fighters . Furthermore, Greek mercenary soldier, Xenophon , also stated that Greece’s rugged terrains largely limited livelihood to cattle breeding which could be managed by the women and the elderly, thus ‘freeing’ the men as warriors which made valuable export commodity. This made it easy for Persia to hire them.

Persian Warrior Classes

Overview

As a result of the assimilation of soldiers from conquered territories and the employment of mercenaries, the Persian army soon comprised of men from many various regions. As cited by Siegfried (2010), this included archers from Ethiopia and the Saka tribes, horsemen from Khorassan as well as swordsmen from the Euphrates, Indus, Oxus, and the Nile.

The usual tactic employed by the Persians in the early period of the empire, was for the sparabara, or shield-bearers to form a shield wall that archers could fire over. Once they wore down their opposing army, they then employed shock attacks with their heavy infantry, the cavalry, as well as the Immortals, who carried wicker shields, short spears, swords or large daggers, with a bow and arrows, to defeat the enemy (as cited in Lazenby, J. F. 1993).

Persian Archers

The Persian archers were one of the bravest fighters in the Persian army. They were located at the front line of attack, raining volleys of arrows down on the opposing force after the Chariots begin the war. The archers were also held much high in regard, with the bow being the national arm of the ancient Achaemenid Empire.

The Persians specially hired the Saka (Scythian) archers to train them in the art of archery to be utilized in their advantage in the war. In addition, they adopted and modified the Scythian bow to a composite recurved bow made of wooden material instead and a cord which enabled greater flexibility when releasing the arrow. The arrows they used were also lighter and bronze at the tip. According to Xenophon, the Persian archers even out-ranged the Cretans, who were renowned Greek specialist archers.

The Scythian bow and arrow proved so impressive that even light infantry soldiers armed with a short spear and a sword carried their bows and some arrow.

Through the adoption of the Scythian bow and arrow as well as their military techniques, the Persian archers were consequently widely considered to be some of the most superior archers of the time. Their attacks were also claimed by Xenophon to be key in the success of many great battles fought by the Persian warriors during the expansion of the Achaemenid Empire.

Cavalry

Studying his Greek enemies, Cyrus the Great realized the importance of cavalry to an army, which could move quickly over extensive distances. He adopted the tactics from the Khorassan horsemen and constructed the Persian cavalry into the world’s largest mounted army and redeployed the Persian army on his own!

The greatest number of the Persian cavalry were the lightly armed soldiers with the simple Scythian bow, formed mostly by troops of diverse nationality. The strategical role of this infantry was to pester the enemies and draw them into battles. The heavy cavalry was almost made up of exclusively regular Persian units. Before then, the cavalry was armed with the standard weapons of the Persian infantrymen: bows, battle-axes, and oval shields. Later, they modified and were re-equipped with short stabbings and throwing javelins instead. Long lances made of wood or entirely of metal, oval shields, and spears were used too.

The diversity of warriors that Persia had gave them an advantage in the military formation, militants of different weapon classes were grouped together and allowing the Persian Commanders to send forth their most effective troops against their enemies.

Chariots

The Persians wanted to disrupt the Greek’s orderly lines to allow their own archers to aim as many Greek soldiers as possible. Thus, they decided to deploy the scythed chariot, an ancient war chariot, with one innovation setting them apart from other armies.

The scythed chariot had swords connected to the rotating axles at the wheels of the chariot, so that as the chariot drove pass, the swords sticking from either side of the wheels would swivel with such speed that any victim in proximity to the sides of it would get their limbs and any other body parts either sliced off or deeply cut enough to cause permanent damages.

With the aid of the scythed chariot innovation, the Persian army managed to effectively break the Greek’s heavy infantry formation, securing their victory.

War Fleets

The Persians adopted Greek war ships called triremes and biremes. The long narrow ships triremes, supported three levels of rowers which included a long oar behind for steering, and at the front of the ship, a ram, made of an iron beam. The ram is used to stab into an enemy ship, attacking it and then successfully destroying parts of it. On the other hand, the bireme is identical to the trireme except it sustained two levels of rowers, which had about 200 men as compared to 300 men found in the triremes. With the Greek culture playing a major role in Persian Navy, it had allowed them to secure a stronger naval presence through the Greeks’ innovations.

Conclusion

All in all, it is evident from the examples of warrior classes above, how the Persians’ ethnic inclusion manifested in its adoption of various military tactics and weaponry from the different cultures they were exposed to. However, this inclusion of cultures by the Persian kings could be largely due to technological determinism.[3] The tolerance and openness for the different cultures might just be a facade or means to import superior weapons and tactics which might give Persia an edge in the expansion of the empire. In this view, “Military technology is the trigger that fires the gun of historical evolution”.

Appendix

Notes

- There has been much debate amongst historians with respect to Herotodus’ account of 2,100,000 soldiers comprising the Persian army. Careful examination of topography, logistics as well as the organization of the combatant troops has enabled historian F. Maurice to arrive at a reasonable figure of 150,500 for the Persian forces.

- Herodotus’ assertion that the Persian infantry “wore no armour over their clothing, for they fought as it were naked against men fully armed” when battling the Greeks, has been proven otherwise in Michael B. Charles’ research, which stated that the Persians DID wear armour and that this claim either reflects the armour worn by a Persian infantry force fighting far from home towards the end of a long campaign, or a broad generalization as juxtaposed to the heavily armoured Greek soldiers. As mentioned in Class 8: Persia, it is also worthy to note that Herodotus, being a GREEK historian, may bring an aspect of historical bias to his views.

- Technological determinism: The idea that the weapon or tactic is the decisive key item that could by itself win battles, or make a significant difference to their outcomes.

References

- Ali, Noor, et al. “The Influence Weapons And Armors Between Persia, India, And Greece During The Iron Age.” 3 May 2012, pp. 1–113.

- Axelrod, Alan and Michael Dubowe. Mercenaries: A Guide to Private Armies and Private Military Companies. CQ Press, 2014. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

- Charles, Michael B. “Alexander, Elephants and Gaugamela.” Mouseion: Journal of the Classical Association of Canada, vol. 8, no. 1, 2008, pp. 9–23., doi:10.1353/mou.0.0058

- Charles, Michael B. “Herodotus, Body Armour and Achaemenid Infantry.” Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, vol. 61, no. 3, 2012, pp. 257–269.

- Fagan, Garrett G. and Matthew Trundle. New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare. Brill, 2010. History of Warfare. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

- Herodotus, The History of Herodotus, translated by Macaulay, G.C. Macmillan, London and NY, 1890.

- Konijnendijk, Roel. “Neither the Less Valorous nor the Weaker”: Persian Military Might and the Battle of Plataia. Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, vol. 61, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1–17.

- Maurice, F. “The Size of the Army of Xerxes in the Invasion of Greece 480 B.C.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 50, no. 02, 1930, pp. 210–235. doi:10.2307/626811

- Olmstead, Albert T. History of the Persian Empire. Chicago, Univ. of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Siegfried, Edward J. “Analytical Study of Battle Strategies Used At Marathon (490 BCE).” U.S. Army War College Strategy Research Project, 2010.

- Summerer, Lâtife. “Picturing Persian Victory: The Painted Battle Scene on the Munich Wood.” Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia, vol. 13, no. 1/2, Mar. 2007, pp. 3-30. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. doi:10.1163/157005707X212643

- Xenophon, Anabis, translated by H. G. Dakyns. Project Gutenberg, 2008

Originally published by Hello World Civ, 02.26.2017, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.