By Dr. Scott Hippensteel

Associate Professor of Earth Sciences

University of North Carolina

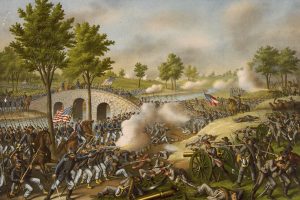

I grew up close to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and spent countless hours as a kid climbing around and through the famous igneous rock fields of Little Round Top and Devil’s Den. No other Civil War site better elucidates the role of geology on the infantry combat of the Civil War. Many years later I was retracing the path of an ancestor who fought at the Battle of Antietam. William Tritt was a member of the 130th Pennsylvania Regiment that assaulted the sunken road (Bloody Lane) at the center of the Confederate defenses. The rocks on this Maryland battlefield are completely different than those found at Gettysburg, only 60 km to the northeast. Instead of the softer sandstones and harder igneous rocks at the Pennsylvania battlefield, Antietam is underlain by carbonate rocks. These calcite-rich limestones and dolostones have weathering characteristics that create terrain that was exploited by skilled commanding officers – in some ways similar to what Union General Meade did with the igneous ridges at Gettysburg.

Apparently this is what happened with my ancestor’s regiment as his entire division approached the Confederate line — they remained concealed behind the rolling hillcrests in front of the Confederate infantry and artillery. When finally taking up positions for firing and attack, they found themselves on a ridge of especially hard limestone only 75 meters from the sunken road, in a perfect position for enfilading fire from above. At such a distance they could fire and take cover behind the hillcrest to reload, or simply fire and charge with bayonets, knowing the Confederates could fire only a volley or two given the slow reloading rate of rifled-muskets in 1862.

The difference in the terrain across this portion of the Antietam battleground and that of the earlier, and bloodier, morning phase of the battle is the result of geology and climate. The carbonate rocks around the sunken road belong to the Elbrook Formation, a combination of softer limestone, dolostone, and shale. The weathering of this heterogeneous rock produces rolling terrain. Had the 130th been a part of the attacking regiments sent across the cornfield during the earlier morning-portion of the battle to the north, they would have been crossing a completely different type of limestone – a nearly pure carbonate that weathers with little relief. The flat terrain produced significantly higher casualty rates for the attacking soldiers. In short, the differential weathering between limestones created a terrain that favored the attack on the sunken road by my ancestor’s regiment.

My recent article published by the Geological Society of America discussed the role of carbonate rocks on infantry tactics in a themed issue of the journal Geosphere (“Human Dimensions in Geoscience”) and I used Antietam as a case study. I also wrote about the Battle of Stones River because it is a second example of the under-appreciate role of carbonate geology in the Civil War. By 1862 most portions of central Tennessee had been clear-cut of trees for agriculture. Around Murfreesboro, forests only survived if there was limestone close to the surface (preventing tillage). These pockets of woodland provided concealment for the attacking Confederates during their initial massive assault, reducing the effectiveness of both Union artillery and small-arms. The Union line faltered and fell back until the center of the line made a stand in the most ideal defensive position, geologically, to be found on a Civil War battlefield. Karrens (or “cutters”) form a series of natural limestone trenches that are approximately a meter and a half wide and deep. The resulting strong natural defensive breastworks allowed the Union infantry to slow the Confederate advance for many hours, ammunition allowing, until a new defensive position could be reorganized to the rear. It could be argued that these rocks saved the Union army from a complete disaster during the battle of Stones River.

The landscape at Devil’s Den at Gettysburg makes it demonstrably the easiest place to contemplate the role local geology had on combat during the Civil War. Famous and disturbing photographs taken by Alexander Gardner of dead Confederate soldiers scattered amongst the boulders only sharpens this image. I would argue that had Gardner travelled to central Tennessee during late 1862, the karrens at Stones River might be an equally famous site. Weathering of limestone created many important landscape features that were critical for the success of both armies during the Civil War, and the geology of these ridges and rolling hills are under-appreciated from a military history perspective.

Differential weathering of carbonate rocks creates sharp-sloping ridges that are ideal for defensive tactics (e.g. Snodgrass Hill at Chickamauga) or rolling terrain that favors concealment, cover, and attack (e.g. southern portion of the Antietam battlefield). The impact of carbonate rocks on tactics is dependent on geographic scale: On a local level, features such as natural trench karrens markedly favors a static defensive position. On a slightly larger scale, this same limestone was responsible for the forests found over shallow rock outcrops, and the woods provided concealment and advantage for attacking troops. On a regional scale, the rolling terrain from differential weathering was ideal for large formations of men to advance across the landscape while hidden in swales or to fire and reload while concealed on the reverse slope of a hillcrest. Conversely, enriched limestone (rock interbedded with the hard silicate mineral chert) produced long ridges of high ground that were ideal for defensive artillery or infantry positions (e.g. Snodgrass Hill, Chickamauga).

My analysis found that on the largest scale – casualty rates from battles grouped by underlying geology – all of these limestone-related factors appear to balance. That is, it didn’t really matter if a soldier was attacking across limestone, igneous and sedimentary rock, or terrain underlain by sand and clay, the casualty rates were consistently between 12 and 15 percent. It seems inarguable, however, that at a local scale carbonate geology favored commanders who exploited the rock. Consider the positioning of Union soldiers in the karrens of Stones River, or General George “The Rock of Chickamauga” Thomas’s stand on Snodgrass Hill. Geology tended to favor the army on defense, whether the Union defending the diabase ridges overlooking Pickett’s Charge or the Confederates during the morning fighting at Antietam.

Gettysburg has rightfully received the majority of study regarding the relationship between geology, terrain, and tactics. Nevertheless, it was carbonate geology, and the resulting landforms, that influence the fighting between the armies at significantly more battlefields, including Antietam, Stones River, Franklin, Cedar Creek, Chickamauga, Nashville, New Market, and Monocacy, and this limestone and dolostone should receive the same consideration from historians as that given to the dramatic outcrops of diabase underlying the Union line at Gettysburg.