We do not have the impression of knowledge clouded by distance.

By Dr. Chiara Palazzo

Researcher

Queen Mary University of London

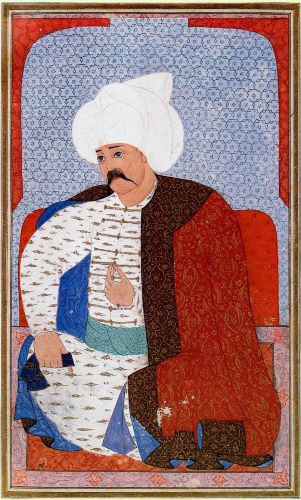

On 23 August 1514, after a long march across Turkey, the Ottoman army of Selim I finally encountered the Persian troops of Shah Ismail on the plain of Chaldiran, north-east of Lake Van, in present day northwestern Iran. It was the culmination of a great military campaign, successfully conducted by Selim: in Chaldiran, with the decisive support of the artillery, the Ottomans were able to defeat their enemy, opening their way to Tabriz.1

Selim took Tabriz, though he later left the city and did not pursue his conquest of the Persian territories further; nevertheless, he prostrated Ismail’s military power and established a border between Turkey and Iran that remains almost unchanged to this day.2 The celebration of this triumph stands out in the copious poems on the life and deeds of Selim, yet the significance of Chaldiran was not so clear and simple to western observers in 1514.3 For a couple of months nothing was known in the West of what had happened, until, at the end of October, the news began to spread, initially in Venice and Rome, and then across Europe. Reconstructing the complex transit of information (and sometimes misinformation) regarding these events, what was said and unsaid, guessed or invented, divulged or covered up, allows us to investigate the workings of the Venetian news network: one of the most complex and sophisticated European networks in the early sixteenth century.

In Rome the pope was certainly concerned about a possible Ottoman victory over Persia; the kingdom of Hungary was an interested observer too, owing to the closeness of its borders to the Turkish territories. But the Republic of Venice, because of its role in the early modern period as a bridge between East and proves to be the most useful observation point when investigating the circulation of this kind of news in the West: in the sixteenth century, information from the Levant coming through Venetian channels was highly regarded and requested by ambassadors and merchants all over Europe, and the diplomats of many courts, in spite of access to their own networks, often turned to Venice to validate news from the East before judging it reliable.4

Therefore, looking towards the Levant from the lagoon and starting from the battle of Chaldiran, we can reconstruct how foreign news moved through the Venetian Mediterranean network, how it travelled from the East through alternative routes, and how the information collected was then disseminated within Europe. Moreover, operations within the Venetian network at this time reveal a system where the communications infrastructure was in transit—thanks to the development of the postal network—and the language and practice of diplomacy in all the principal European courts was becoming standardised.5

This dynamic leads to further considerations: the circulation of news implies contacts, awareness of different realities, geographical and cultural reference points, the development of the collective imagination. One may wonder what kind of perception the Venetian public had of distant geographical and political realities such as Ismail’s Persia, an East that was even more remote than Constantinople, and perceived as even further away than it actually was, due to lack of information. Where and how could news be gathered about these places? How long did it take to reach its destination? What did the public in squares and marketplaces actually come to know? And through which channels and media? The available sources allow us to observe how an item of Eastern news could circulate widely and how fascinating accounts of distant conflicts could become available, in Venice or in Rome, to anyone who bought a cheap pamphlet or even stopped to listen to verses recited by a ciarlatano or charlatan.

In 1514 the Roman diarist Sebastiano di Branca Tedallini wrote “Nello mese di agosto venne la nova in Roma come lo gran Turcho è gito a campo allo granne soffì in Persia e feceno fatto d’arme insieme; lo gran Turco fu rotto et morsero delle persone cento trenta milia et dello detto soffì morsero delle persone trenta overo quaranta milia” (“In August we have news in Rome that the Great Turk had declared war on the Great Sofi in Persia and they fought; the Great Turk was routed and 130,000 of his men died as well as 30,000 or even 40,000 of the Sofi’s army”).6 At first glance, these lines seem to allude to the battle of Chaldiran, except that they reverse the final outcome, attributing the victory and destruction of the enemy to Ismail (known as ‘the Sofi’ in western Europe). Is this a misunderstanding? It would have been impossible for Tedallini in Rome to hear real-time news of something that happened almost at the other end of the world. The combat reported by Tedallini was not that pitched battle and indeed probably never took place. In all likelihood the diarist was reporting an unreliable account that had reached Rome on 3 August, one of many that circulated in the West during the Ottoman advance across Persian territory, announcing what Christian Europe wanted to hear: a great victory over the Turks.7

That such an item was recorded, and turned out to be unfounded, is not particularly surprising. It is more significant, however, that Tedallini did not write a word about the later news of Chaldiran, though in Rome the fact did have resonance, eliciting comments, opposing opinions and interpretations. The absence of any reference to Chaldiran and to the actual conclusion of the Ottoman campaign is to some extent owing to the concise form of the diary; nevertheless, we will see that the peculiar routes and channels through which news of the battle spread to the West managed substantially to complicate the understanding and interpretation of the event for the public in European cities.8

While Rome called for the Ottoman defeat, even distorting and exaggerating the successes of the Persian army, another Italian city closely monitored the development of the Ottoman campaign as no other court in Europe could. In the months leading up to Chaldiran, the Republic of Venice regularly received detailed accounts from the bailo in Constantinople, Niccolò Giustinian. He transmitted reports from his dragomanno Alì Bey, who was following the Turkish army; furthermore, he collected more news conversing with Ottoman pashas and using his network of informers both inside and outside Court.9 On several occasions the Republic could also rely on reports from Donado Da Lezze, podestà of Rovigo and a great expert on Levantine affairs. Thanks to his correspondence with the Armenian bishop in Cyprus, he was well informed about the developments of the political situation in the East and, with the help of a native of Vicenza, who had great experience of the territories the Ottoman army was now crossing, he was able to comment on the news and predict the Turk’s next move.10

In spite of this complex of information channels, initially Venice could not have anything other than an approximate and contradictory picture of the decisive events in the campaign. A considerable stream of news reached Venice during the months following the battle. However, the multiplicity of reports and their conflicting interpretations created an intricate and complicated tangle of rumours and writings spreading from one end of the Mediterranean to the other.

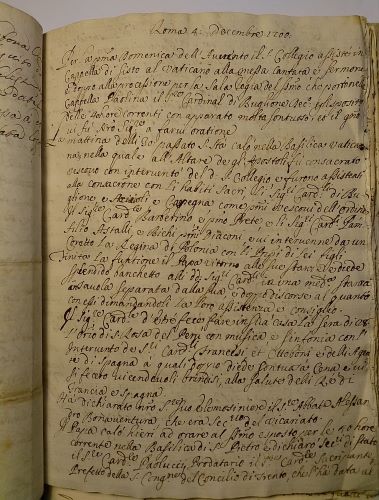

Though Venetian diplomatic documents from the first half of the sixteenth century are incomplete, we do possess consistent documentary evidence regarding Chaldiran.11 Thanks to the diary of the Venetian nobleman Marin Sanudo, we have been able to recover part of the official correspondence between the Venetian representatives and the Senate (often with reports attached) and fill in the large gaps in the Archive. Many dispatches were transcribed either entirely or partially, together with extracts from merchant and private letters. Sanudo noted the arrival and departure date of each letter and sometimes provided some details about its route. His comments also indirectly recorded some oral accounts: conversations and rumours circulating in the city.12

This heterogeneous collection of supporting material provides quite a complete picture of the news directed towards Venice, of the speed at which it travelled and the hubs through which it passed. References in the letters allow us to follow the multiple streams of information originating from the event itself and to see how, at each hub, news items were gradually enriched, re-elaborated and channeled on to the next point. By this means we can obtain a schematic map of routes and times. Furthermore we can understand something of the convergence of these information channels and analyse the public’s reception and consumption of news, the perception of both the political class and the ordinary people on the street.

Nevertheless, what can be derived from the documents recorded by Sanudo and the few remaining dispatches held in the Archives still raises significant questions. We find many different versions of events which disagree in many respects, and sometimes even on the crucial point of who actually won the battle. Indeed, while some sources report a Turkish triumph, others instead declare the Sofi victorious and suggest that Selim was trying to distort the real outcome of the battle by sending out messengers and couriers to celebrate a false victory and spread false reports. The uncertainty persisted, in spite of the accumulation of information during the following months, and the impatience of those courts which usually depended on Venice for information regarding the East can clearly be perceived in official correspondence.13

Focusing on the documents concerning the last part of Selim’s campaign (from July to December 1514) we can see that the news pouring into the network came from more than 30 different and widely dispersed observation points. They make up a branched web that spans across the Mediterranean basin, from the coasts of Syria and Egypt to Sicily, while also encompassing the Dalmatian coast and a few European cities such as Buda and Rome. The distribution and density of these outposts are fundamental: they characterise the network in different ways, enlarging or limiting the range of an item of news, affecting speed, completeness and reliability.

Constantinople played the key role in channelling the principal information flow: 22% of the news we can draw from available documents today come from there, first and foremost the Venetian bailo’s dispatches.14 His letters followed three routes, often used concurrently: to ensure that his mail would arrive safely and on time, the bailo would entrust copies of the same letter to different couriers who then followed different itineraries.15

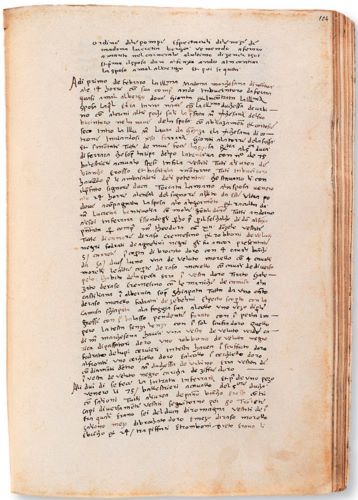

The first of these routes passed through Edirne, the valley of the Maritsa river, touching Filippopoli (Plovdiv) and Skopje, and then crossed the Plain of Kosovo to Pristina. From here the most difficult and impenetrable part of the route started, through Montenegro and the Albanian Alps directed towards Ragusa (Dubrovnik). The second route, to Corfu—another major hub of the Venetian network—passed through Rodosto (Tekirdag), Kavala, Thessaloniki, and Ioannina. The mail then reached Venice by sea, often making one or more stops at Ragusa or another port along the Dalmatian coast. More mail usually arrived at these coastal cities from the inland areas: this sometimes included the correspondence of the Venetian ambassador in Buda. Yet another possibility was to land in Otranto or Trani and follow the route to Venice via Naples and Rome. To guarantee a faster delivery of official mail a brigantino or a gripo often covered the last part of the journey (from Ragusa to Venice or from Corfu to Venice).16

Though mail services were not yet regular, the Venetians were able to supply their government with quite a systematic stream of news. From the end of the fifteenth century the Republic used the Courier Company of the Serenissima for their European connections; but for land routes to the Ottoman capital specific postal couriers were employed, generally Slavs, often coming from Montenegro.17 These travelled mainly on foot, covering 40, 50 and even 60 km a day. They were very well paid: in April 1514, for example, a courier received 40 ducats to deliver the bailo’s letters to Venice, a good sum if you consider that the tariff from Venice to Rome in the 1530s was 10–12 ducats.18

Correspondence could also be transported on merchant ships and galleys. This third sea route passed through Gallipoli and Chio, then coasted Morea, touched on Zante and Cephalonia and joined the second route at Corfu. Extant documents allow us to track the journey of one of these galleys, loaded with a cargo of cured meats, which also carried correspondence to Venice: it set sail from Constantinople on 17 November and reached Corfu just 20 days later—its arrival was recorded in a Venetian dispatch from the island. It finally reached Venice on 28 December, delivering official and mercantile correspondence, taking 41 days in all.19 The Venetian bailo normally wrote to Venice twice a month. His letters took about 30 days, or a little longer in good weather, but could take over twice as long in winter (40 to 90 days, or even more) when roads became impassible due to snow, and navigation was reduced or stopped altogether.20

But diplomatic correspondence from Constantinople was not the only relevant source for news relating to Selim’s campaign. Another important flow originated in Iskenderun, on one of the more commonly used trade routes to Tabriz. From here it reached the Syrian cities of Aleppo and Damascus where large Venetian communities resided. These were usually reliable sources: at that time they were particularly attentive to the situation as they feared that Selim could divert his path and head towards Syria.21 From the Syrian coast the information headed to Cyprus, where news collected by Venetian merchant communities in Egypt also converged. Then, en route to Venice, other minor branches joined the main flow from Rhodes and Crete, from Constantinople—by sea—or from Greece and the Ionian Islands. Finally the entire flow reached an intersecting point in Corfu joining the aforementioned current from Constantinople.

Though the network of outposts hosting Venetian diplomatic representatives can be considered the essential architecture of the news flow, the collaboration of merchant networks simultaneously operating within the same territory should not be underestimated. As the documents regarding Chaldiran demonstrate, we have an increasing flow of information from the East thanks to circuits other than those of diplomacy, and a high degree of permeability between diplomatic and mercantile information. Ambassadors and representatives of the Republic often included merchant news in their dispatches and, as we move eastward, these insertions became more frequent. Diplomatic observation points became rarer and rarer and the lack of official and reliable sources led the Venetian authorities to seek additional validations and comparisons, thus involving other observers and other perspectives (the Syrian inland cities, for example), which often reported the same news item, transformed and mutated by its passage through different channels and different opinions. In these cases we have a perceptible fragmentation of sources, which was unlikely to occur in the more consolidated areas of the network, and this affected the quality of information received. During the months after the battle of Chaldiran, practically every ship, mariner or merchant travelling from the East to the Mediterranean could have collected and imparted his version of events, either as an eyewitness or because he had heard rumours or the testimony of witnesses, and many such reports, in the absence of more reliable sources, became part of the information evaluated by the Venetian government.

Venetian dispatches and merchant letters, therefore, abounded in references to oral sources, speeches, conversations, the accounts of witnesses and reports from crews. In a dispatch from Corfu, for example, a crew coming from Cyprus was the source of news reporting the Turkish rout and that crew, in turn, had heard the news from another ship from Rhodes. The other dispatches from the island often mentioned the reports of couriers, opinions of patricians, unspecified voices from Rhodes and Morea, and even what seems to have been a quarrel between a Christian merchant and a Turk, the former convinced that the Ottoman victory was a lie and the ‘infidel’ instead insisting that Selim had certainly won.22

If we limit ourselves to analysing information concerning the pitched battle, we can briefly reconstruct the circulation of news from the first announcement of a Turkish victory in Venice, at the end of October 1514, to February 1515, when all the principal Venetian outposts in the Mediterranean and across Europe had issued their communications and the Ottoman victory was considered verified.

Selim’s letters from the battlefield took 37 days to reach Constantinople where the Venetian bailo promptly sent a dispatch on the route to Corfu and a copy on the route to Ragusa.23 In spite of the letters and the words of the couriers, the bailo gave no credit to the news of the victory. Trusting reports provided by his informers in Constantinople, he wrote instead that the Turks were hiding the truth and, consequently, their declaration was not reliable.

Eighteen days later, news of the victory in Chaldiran reached Ragusa, reported by Ottoman couriers bringing letters from the Sultan addressed to the Senate of that city. The Venetian provveditore, who commanded the fleet in Ragusa, immediately sent a dispatch to Venice, based on the Ottoman messengers’ words alone, as the bailo’s letter had not yet arrived. Consequently, he reported as “the most certain news” that the Sultan had crushed the Persians in a ferocious battle: “È stà grandissima strage da una parte e l’altra, e morto uno bassà dil signor turcho et altri sanzachi; siché ha auto etiam il turcho una gran streta, ma è restà vincitor unde ha mandato [messeggeri] a tutti quelli lochi soi a far festa” (“It was a terrible massacre for both armies, an Ottoman bassà and other sanzachi died; thus the Turk suffered a great assault, but at the end he won and sent [messengers] to all his territories to celebrate”).24

This dispatch reached Venice on 31 October, taking 14 days and was the first piece of news on Chaldiran, arriving 69 days after the event. This same news item was also transmitted from Ragusa to Rome, where the Venetian ambassador could attach a copy of Selim’s letter to his dispatch.25 The bailo’s dispatch from Constantinople, by contrast, which repudiated the Turkish victory, took 24 days to reach Corfu. It was promptly re-addressed to Venice, but the official mail reached the lagoon only 19 days later, noticeably preceded by letters sent the same day by business partners of the Aurami family, a merchant family residing in Venice. The letters reported that Selim had won a great victory and that he had “dressed our bailo and other merchants in gold”.26 These letters, confirming what the Republic had already learned from Ragusa and Rome, were also read in the Senate.27

Giustinian’s letter finally arrived in the lagoon on 12 November. Until that moment the ‘most certain news’ about Chaldiran was only from Turkish sources, and therefore a skeptical attitude was quite understandable: Selim certainly wanted to convey a triumphant image of his campaign to the West. Venetian skepticism was also justified because of the conflicting news that had been circulating during the previous months. News of a Turkish retreat had been repeatedly reported in June, and again in August and September, in letters from Corfu, Constantinople and Cyprus, with different accounts of a battle fought in the first days of July or in mid-August; one also included the account of an eye witness, a young Ottoman slave.28

The hypothesis that Selim had not won, and that he was only ‘acting out’ a victory was further strengthened when, on 21 November (90 days after the battle), a ship from Cyprus with a cargo of wheat delivered letters from the Venetian merchant communities in Syria.29 We know of these letters only through Sanudo’s brief reference to them, nevertheless it is enough to know that they reported whispers of a Persian, not Ottoman, victory; furthermore they show that some information about Chaldiran had at last reached Syrian outposts. Two days later, a letter from Francesco Foscari, the Venetian captain in Zara, reached Venice, reporting news from a caravel from Parga which had passed through Lepanto: while news of Selim’s victory was being publicly celebrated, rumours were secretly circulating about his defeat.30 More dispatches from Constantinople came at the end of November and, in spite of the reports recently received in the Ottoman capital which confirmed Selim’s victory, the bailo remained convinced that the Sultan was trying to hide his embarrassing rout from the West, and especially from the neighbouring kingdom of Hungary.31 Significantly, it was only on 14 November that the events of Chaldiran were mentioned in the letters of the Venetian ambassador in Buda: however, those letters did not throw any light on the real outcome of the battle.32

On 3 December more letters from Damascus and Aleppo arrived in Venice on merchant galleys: the Ottoman defeat was reported as certain, though no specific descriptions were given.33 In a letter from Aleppo dated 7 October, merchant Girolamo Dandolo wrote to the luogotenente in Cyprus:

fin qui non habiamo auto nova niuna che i siano stati a le man; ma per quello si dize di qui, per Mori, che loro è stati a le man a dì 30 del pasato, perché in quel zorno di qui fu una gran combustion di tempo e di polvere e di rozesa di ajere, tal che tutti dicono loro esser stati alle man quel zorno; ma per esser zorni 20 de camin de qui dove i sono ancora, non se ha potuto haver la nuova, e poi in quella sera medema fu visto, e mi viti, una cometa levarsi di ajere da la volta di Turchia, e andò cussì caminando per ajere verso el paese del Suffi per mexi tre di longo, dove niun pol pensar altramente salvo el turco li è sta roto.34

(till now we have had no news of combat, but according to the Moors, the battle was last month on the 30th, because on that day a big cloud of red dust was seen in the air, so that everybody said they were fighting, but the place where they were is a twenty-day walk from here, so we could have no news yet. However, that same evening a comet was seen, and I saw it, rising in the air towards Turkey, and coming to the Sofi’s reign, so that everybody thinks the Turk had been destroyed.)

Red dust and a comet: these were apparently the best sources of news available at that stage, from a Syrian observatory 45 days after the fact.

Between January and May 1515 only merchant letters from Iskenderun and Damascus insisted on Ismail’s victory as an established fact, but the luogotenente in Cyprus, who handled mail from Syria, clearly dissented from this version. By that time almost all other reports confirmed the Ottoman victory, although with attempts to underplay its importance.35 Nonetheless, all doubt was still not completely dispelled because, on 2 June, Sanudo writes in his diary about a report brought on a ship from Corfu telling of a terrible rout suffered by the Ottomans and about 15,000 Turks killed by the Persian troops.36

Therefore, we can identify two principal flows of news from the East to Venice: the first, fed by the words of Ottoman couriers and Selim’s letters, travelled from Constantinople towards Ragusa by land, or to Corfu on the route to Joannina; the second came from Syria, by sea, passing through Cyprus, Rhodes, Crete and Morea, and finally joined the first one in Corfu. We must bear in mind that these two channels did not travel separately, but sometimes crossed at various Mediterranean hubs: Crete and Rhodes, for example, not only received news from Syrian sources, the most confused and imaginative, but were also connected to branches of the flow of news from Constantinople by sea, which carried more reliable information. Conflicting interpretations of the facts were channeled into these two currents: essentially the Ottoman defeat was reported by Syrian cities and echoed in some Venetian sea outposts. On the other hand, in land outposts (in spite of the skepticism expressed by the bailo in the first months) the version carried by Selim’s messengers was given more credit.

Nevertheless, the difficulties in understanding the battle that emerge from these documents do not seem to have been caused by a lack of ability in gathering news (owing to the huge geographical distance between where the facts occurred and where news was collected). Rather, the issue seems to be one of interpretation. In other words, news about Chaldiran channeled through the Venetian network was, on the whole, abundant and detailed, but each person who received and transmitted it added different interpretations and conclusions. The intent was not necessarily manipulative: it rather expressed the intrusion of a desired result introduced into the void in space and time that necessarily existed between the plain of Chaldiran and the lagoon, between single items of news and their deferred receipt.

It was thus possible to deny an outcome which was unfavourable for Europe, and to preserve the idea—deeply rooted in Venice as well as in Rome—of a Christian alliance with Persia against the common Ottoman enemy.37 This project, encouraged by Ismail’s almost unbelievable victories in the first years of the sixteenth century, would have certainly faded if it had been confirmed that the “miraculous” Sofi’s army had been totally destroyed by Selim’s artillery. Repeated requests from Pope Leo X for precise information, reported in the Venetian ambassador’s dispatches from Rome, reveal the need to answer a crucial question: could Ismail be still considered as a useful ally?38

The kingdom of Hungary also requested clarifications from the Republic: at the end of February King Ladislaus complained that the Serenissima had not informed him about Ismail’s victory and had only communicated it to the pope when it had finally been confirmed. This recrimination, first of all, demonstrates that at the end of February the Hungarian Court had no clear idea about what had happened in Chaldiran. But, above all, the Venetian reply to the king’s question sounds significant: on 31 March 1515, more than seven months after the battle, the Venetian Senate, writing to its ambassador in Buda, denied transmitting that news to the pope, and furthermore asserted that the outcome of the battle had still to be clarified.39 In other words, at the end of March Venice could not (or did not wish to) express an explicit opinion about the battle.

However, to fully understand this disconcerting and unresolved question—who won at Chaldiran—we must consider the context and the almost mythical image of the Sofi that had been created in the West, a vision that Europe was particularly reluctant to abandon. As the antagonist of the Turk, the ‘Persian’ had gradually assumed positive Christian-like features. Perhaps the most relevant point was the reputation of his army, an ancient mythical cavalry still fighting with swords and scimitars, which by then had been compromised by the widespread use of ‘cowardly’ fire-arms on battlefields. The Ottomans’ use of artillery in Chaldiran was repeatedly mentioned in Venetian letters, pointing out that without it Selim would have not been able to win.40

Consequently, it is inevitable that Venetian accounts would conform, more or less consciously, to this deep-rooted and pre-existing collective imagination, whereby the Persians, seen as enemies of the enemy, were almost relieved of the usual epithet of ‘infidel’ and on the brink of being assimilated to Christians. In this light, the tenacity with which the Sofi’s defeat was rejected, and even transformed into a victory by some, appears more reasonable; when victory was finally ascribed to the Sultan denial was replaced with a sort of silent assent.

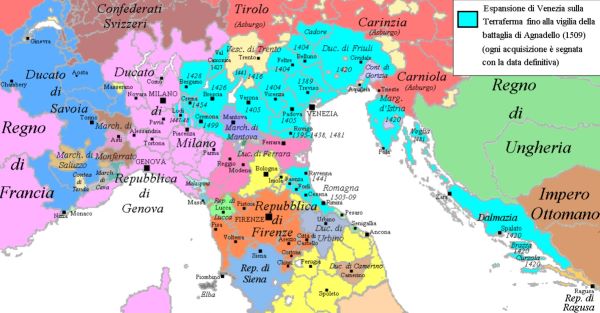

While the Republic was trying to understand what exactly had happened in Chaldiran, and was cautiously weighing the information conveyed to other courts which were waiting for a definitive conclusion, the larger public that crowded the squares, marketplaces and ports of the city was also receiving news of the same events. The documents examined up to now were not completely inaccessible to this wider public: aside from those engaged in politics, a broader portion of the public was able to read many of the letters sent by merchant and private individuals from Constantinople, Cyprus and Syria, and could hear the rumours and reports from mariners circulating in the ‘universal’ marketplace of Rialto.41 They could also hear, read or buy a pamphlet: at the beginning of the sixteenth century, hand-written and printed ‘copies of letters’ circulated widely among people of different social levels, and even an illiterate audience could hear current news in the rhymed compositions of charlatans, often as chivalric poems in ottava rima.42 In the first years of the war of the League of Cambrai, for example, one Venetian merchant would attach rhymed compositions to letters addressed to his brother in Syria to give him some news (‘nove’) about what was happening in the Venetian Terraferma.43 This kind of text however was not exclusively appreciated by the common people: patricians often attended charlatan readings and recitals, and read or bought their verses.44

Printed news pamphlets were heterogeneous in form but had some recognisable features in common: they were made up of a few leaves (usually no more than eight, but more likely six or four), printed on poor quality paper, the title page was often decorated with a woodcut, and they were conceived for instant and immediate consumption. Moreover, they were very cheap (between two and eight denari piccoli): according to Sanudo, in 1518 one denaro piccolo (a bagattin) was the price of a traghetto to cross the Canal Grande.45 From the second half of the sixteenth century the production of printed letters and newsletters increased, whereas versified accounts of news became rarer. Some rhymed compositions on current events still circulated, but they were elaborated texts for the entertainment of a select cultured audience who were also kept up-to-date by other means.46 Nonetheless, when news of Chaldiran arrived, copies of letters and charlatan’s rhymes were still considered information media, and if not equivalent, at least comparable.

In 1514, while the bailo of Constantinople informed the Republic that Selim had not won and the Ottoman celebrations were to be considered fictitious, in a square, perhaps in Venice or in Rome, the voice of a charlatan announced to his audience that they were about to listen to “The rout of the Turk by the Great Sofi in Calamania, a province near the Castle of Lepo, and the death of the great Turk, the death of the Sofi, and battles fought by sea and land”.47 A little later an unspecified Roman printer published a Latin leaflet, which summarised the Ottoman campaign and the battle of Chaldiran.48 These reports, both containing quite extensive narrations of the battle, still survive in two printed pamphlets: the first is a cantare in ottava, by a charlatan named Perosino della Rotonda, probably composed when the news first spread in the West.49 The second, in contrast, is a humanistic letter sent by ‘Henricus Penia’, perhaps a member of the Accademia Coryciana in Rome, to cardinal Bandinello Sauli, and probably printed in Rome in January 1515.50 These short publications need to be contextualised within a a broader output regarding Persia. In the first 20 years of the sixteenth century the catalogue of Italian publications attests to least ten pamphlets regarding the Sofi, and considering the perishable nature of such papers there must have been many more.51 In the majority of these texts information does not seem to be the main purpose. More than current news, they tend to narrate anecdotes about the Sofi, his miraculous conquests and his virtues which are likened to the Christian virtues: Ismail is depicted destroying mosques and preserving churches, adoring the Cross, eating pork and drinking wine as Christians do. He is described as liberal, just and also divinely inspired because his soldiers could perform superhuman feats such as digging through a mountain which was blocking their way by sheer strength.52

But, even if events and battles could be coloured with fabulous features, and quite freely adapted to an anti-Ottoman perspective, the narration had to cite an authoritative source, a trustworthy author, or at least had to have a realistic form and an abundance of detail. In the majority of these products the marvellous dimension, innate in the collective western image of the Levant, coexists with a strong political message. Consequently depictions of the Sofi, whether in pamphlets, dispatches or merchant letters, always tried to narrow the gap between Persians and Christians, legitimising the alliance.

Reading Perosino’s pamphlet it seems quite clear that the author knew very little about the facts. He had probably heard a current account of Chaldiran and decided to fill in what he did not know with invention, while being careful to create the impression of a truthful and detailed narration. He devised a mixture of imaginary elements (such as a naval combat that seems to have never occurred during Selim’s campaign, and even the death of both the Sultan and the Sofi) supported by more realistic descriptions. The geographical coordinates are vague, sometimes fantastic or inconsistent and the date is inaccurate (17 June).53 Nevertheless, the narration of the pitched battle is recognisable even if some crucial details are altered: for example, according to Perosino the Persian artillery launched the first attack, while in actual fact there were no Persian cannons at Chaldiran while the Ottoman artillery was decisive in Selim’s victory.54 Nevertheless, the charlatan’s song, even if ‘imaginative’ in some parts, was not merely a form of entertainment: to an extent it was also a mode of news communication. Perosino was giving news to an audience that, first of all, expected to be informed and was growing used to daily contact with fresh news about current events. At the beginning of the sixteenth century the informative function of versified news was still seen as fundamental, and many charlatans like Perosino presented themselves as professionals of information, always on the lookout for news. They attracted their audience by assuring the truth and ‘freshness’ of their reports and stressing their speed in communicating them.55

In Perosino’s verses the Sofi won at Chaldiran; just as in Venice many people still believed this when the pamphlet was printed. Though doubted, this version of the facts had not yet been disproved, and, moreover, it was the most desirable outcome from a Venetian perspective. It is significant that the charlatan reports, almost literally, the same opinion as the Venetian bailo in Constantinople regarding the Ottoman manipulation of the news to hide a disastrous defeat: even though the Turks spread the word of their victory across Christendom—writes Perosino—their deceit is not believed, they suffered innumerable casualties and, if Christian kingdoms were to join forces, they would destroy the Ottomans definitively.56

It was a particularly appropriate argument at that moment when, in Rome, Pope Leo x was promoting another anti–Ottoman crusade. The charlatan therefore stages a dramatic conversion of the Sofi directly on the battlefield. When the Shah realises that his army is losing the battle, he begins to pray to God Father and Saviour, apologises for not having been a good Christian and promises to baptise all his people. Only then, in the name of the “True God”, does he win.57

While Perosino’s audience listened to this account, the more select public which read the printed epistola addressed to cardinal Sauli obtained information about the same events and also read a brief reconstruction of the entire military campaign. In the epistola the battle of Chaldiran is correctly located, geographically and chronologically: in Persia, at a ford across the Aras river, on the route to Khoy, on August 23.58 The deployment of troops and the dynamic of the battle are faithfully described but, even if the Ottoman victory is not denied, the author underlines some details to transform it into a qualified success. First of all, the Turks were badly equipped, so that the Persian cavalry could easily crush them in the first attack and only the artillery obliged the Persians to retreat.59 Secondly, Penia, the author of the epistola, guaranteed that the Persian army was able to recover. Eight days after the battle Ismail organised a night-time ‘raid’ on Selim’s tent in an attempt to kill him: the raid failed but the Sultan was obliged to beat a hasty retreat.60

Curiously, a report from Iskenderun, dated 12 November and attached to an official dispatch from Cyprus, pointed to a similar episode: during the battle four Turkish soldiers deserted and proposed to kidnap Selim and deliver him to the Sofi. When they arrived at the tent however, they found the Sultan guarded by his Janissaries. Aware he was in danger, Selim ordered his men to open fire, although the battle was in full course and he would inevitably also hit some of his own men.61

Penia was certainly better informed than Perosino, whose partly fictitious narration for street consumption used fragments of information on a clash between Persians and Ottomans recently fought in a distant corner of the world. Penia’s account instead draws, as he points out, on a report from one of Selim’s messengers sent from the battlefield, and from the letters that he carried, specifically addressed to the Republic.62 Penia supplies his readers with a particularly precise account, yet his description is quite different from those letters: it is closer to Venetian sources, and more fitting for an interpretation suited to European readers. Penia’s work had a precise first addressee and his message needed to be in tune with the Roman academic context and the papal court. The author of the epistola therefore does not deny the Ottoman victory, yet neither does he clearly state the outcome of the battle: at Chaldiran the Persians retreated under Ottoman fire, but he immediately plays down the retreat by referring to the attack on the Sultan’s tent which shows Selim in retreat, information probably taken from a source related to the Syrian report from Cyprus.

Two pamphlets therefore, composed in very different milieux, in different languages (in the vernacular and Latin), presumably addressed to a different public and published at different times, reported two versions of the same news item and provided information of a different quality. Yet they played a similar role and actually suggested the same political message: the Turks had been defeated or weakened, and it was time for the West to attack.

There was, however, surely more to these reports than political or strategic wish-fulfillment. These accounts of distant peoples and unknown places, whether real or invented, were in any case fascinating and stimulated audiences in European cities to be more aware of those peoples and countries, to situate them on a mental map, and to feel those stories as more concrete and contemporary with their own lives. The case of the battle of Chaldiran demonstrates how Persia seems to have moved noticeably closer in the perception of western observers during the second decade of the sixteenth century. In those lands, traditionally the settings for marvellous tales rather than news, something crucial was happening, something that could have serious repercussions for Christian Europe.63

In February 1506, the Venetian merchant and diarist Girolamo Priuli declared, reporting news regarding the Sofi, that though it would in fact be necessary it was impossible to know the real truth of those events, “because they had occurred in countries too remote”.64 Nevertheless, analysing the spread of news from Chaldiran, we do not have the impression of knowledge clouded by distance; it is rather an over-interpretation of the available data.

Sixty-nine days elapsed before news of the battle fought in Persia reached Venice: not too much time considering, as we have seen, that correspondence from Constantinople seldom took less than a month even during the favourable season. But the point is that more than seven months had passed before the veracity of that news could be unequivocally and definitively determined. An extended network covering the Levant and Mediterranean areas was involved in transmitting news about Selim’s campaign, while European outposts played a marginal role even when they were directly involved (the kingdom of Hungary, for instance). European observers seemed to be waiting for news rather than providing it. Venetian diplomatic and merchant networks cooperated, and indeed merchant news was sometimes faster than diplomatic dispatches and no less reliable. While an abundant and mixed flow of news reached the political centre in a relatively short time, these items produced a clamour of dissonant voices. The substance of the communication was unclear. There were no reliable observers on-site, because the diplomatic network did not stretch beyond Constantinople or Aleppo. Moreover, only voices and accounts of fortuitous witnesses could be gathered alongside Selim’s letters and his messengers’ words. Therefore, the problem was not the lack of news, but an overflow of uncertain reports that were difficult to verify. For this reason Venice released the information it collected with extreme caution: in communications with other courts the Republic neither confirmed nor denied the news of the Ottoman victory, for as long as this reticence was possible. Certainly, the Venetians were hardly anxious to validate such an unfavourable piece of news: victory implied further enlargement of the Ottoman Empire and greater pressure on the borders of Christendom. Moreover, a Turkish triumph could affect Venetian commerce in the East and, even if the Republic had more pressing military problems in its own territory at that moment, because of the war of the League of Cambrai, the oriental market was still crucial to its economy.

As we have seen, the news of Chaldiran underwent considerable modifications during its journey westward, obscuring the facts to a point where the truth became indistinguishable. Venice was able to control the political information addressed to the European courts, delaying a ratification of Selim’s victory. Moreover, by avoiding a clear position on the credibility of the Ottoman news, the Republic allowed doubts and alternative versions to persist, versions better suited to the interests of the pope and Christian Europe. Consequently, in Rialto and in Roman squares people discussed conflicting accounts, grounded mostly on Venetian news; the charlatans enchanted their audience with stories of remote countries, but above all celebrated the desired but unverified outcome of the battle against the Turks. Even the more reliable report of the Latin epistola provided a softened version of the information, offering a more favourable interpretation to cater to the wishes of Christianity; to the extent that, as far as the West was concerned, Selim never really won, and Tedallini could quite easily forget to note it in his diary.

Chapter 37 from News Networks in Early Modern Europe (849-869), DOI:https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004277199_038, published by Brill Publishing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.