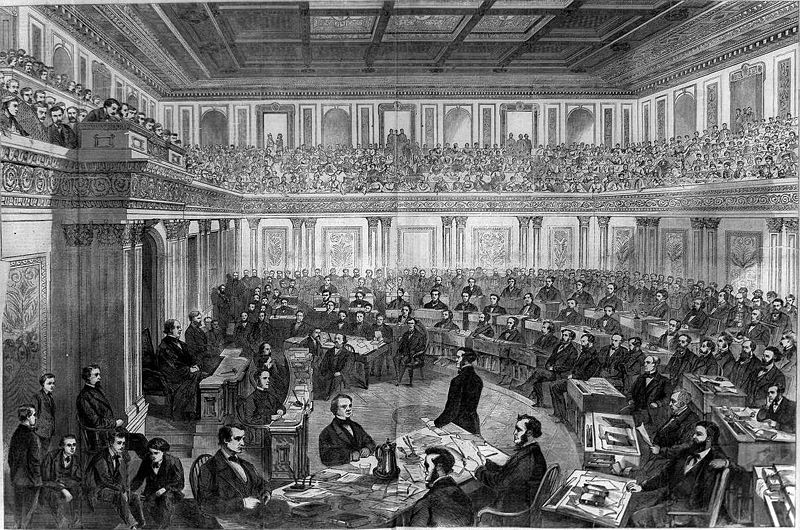

The 10th article of impeachment against Andrew Johnson in 1868 was about his language and conduct over the course of his term.

By Jamelle Bouie

There’s precedent for making transgressive presidential speech a “high crime or misdemeanor.” The 10th article of impeachment against Andrew Johnson in 1868 was about his language and conduct over the course of his term. Two years earlier, Johnson had taken a tour of Northern cities to campaign against Radical Republicans in Congress and build support for his lenient policies toward the defeated South.

At first, it was a success, in Baltimore, New York and Philadelphia. But his fortunes turned in Cleveland, where the stubborn and taciturn Johnson unraveled in the face of hecklers. “The president was frequently interrupted by cheers, by hisses and by cries, apparently from those opposed to him in the crowd,” William Hudson, a reporter for The Cleveland Leader, wrote. When a heckler yelled, “Hang Jeff Davis!” — referring to the former leader of the Confederacy, then held at Fort Monroe in Virginia — Johnson replied, “Why don’t you hang him?” When another shouted, “Thad Stevens” — the chief Radical Republican in the House of Representatives — a now angry Johnson responded with “Why don’t you hang Thad Stevens and Wendell Phillips?” Phillips had been a leading abolitionist.

Johnson continued to speak, struggling to gain the upper hand with the crowd. By the end, however, the president was unhinged. “Come out where I can see you,” he said to one heckler. “If you ever shoot a man, you will do it in the dark and pull the trigger when no one else is by to see.”

By the time the tour was over, Johnson had been humiliated and his reputation was in tatters. All of this would resurface in 1868, when the House adopted its 11 articles of impeachment against the president. Among them was a reference to his summer swing through the North — to the idea that Johnson had sullied the office of the presidency with dangerous, demagogic rhetoric.

Article 10 was divisive. Not necessarily because the Congress or its Republican majority had any love for Johnson, but because it raised difficult questions. How could anyone prove that Johnson meant to “impair and destroy” the regard of Congress? And the president is entitled to the same freedom of speech that any other citizen has. His rhetoric was offensive, but was it impeachable? Johnson’s opponents in the Senate opted not to test the case.

Originally published by the Austin-American Statesman, 10.04.2019, under a Creative Commons license.