In times of national triumph and tragedy, he gave voice to the conscience of the country.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

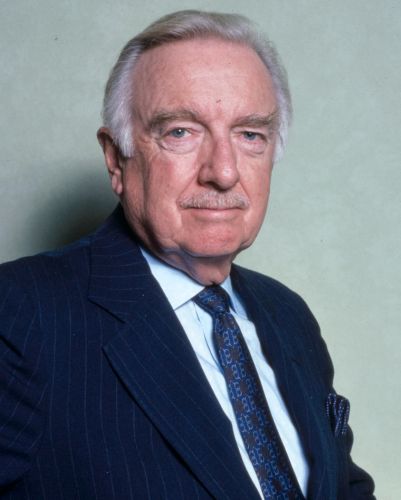

Walter Cronkite, the long-serving anchor of the CBS Evening News, is often regarded as “the most trusted man in America.” This title was not given lightly, nor was it simply a media creation; it was the result of decades of consistent, fact-driven journalism that came to define an era of American news broadcasting. Cronkite’s tenure on television coincided with some of the most turbulent decades in American history—spanning the Vietnam War, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the Apollo moon landings, and the Watergate scandal. In each instance, his calm demeanor, rigorous reporting, and ethical standards set a high watermark for journalistic integrity. This essay explores how Cronkite earned and maintained public trust, the social and political impact of that trust, and the implications of his legacy in a fragmented media landscape today.

A Journalist’s Journalist: The Rise of Cronkite

Walter Cronkite began his journalism career as a wire service reporter with United Press, covering World War II from North Africa and Europe, including the Normandy landings and the Battle of the Bulge. His reporting was lauded for its clarity and accuracy, qualities that would become his hallmark as a broadcaster. Cronkite joined CBS in 1950, first anchoring its Washington bureau and later hosting various programs before assuming the anchor role for the CBS Evening News in 1962.1

From the outset, Cronkite positioned himself not as a personality but as a conduit of facts. He maintained a strict adherence to objectivity, rarely offering personal opinions on-air—save for a few notable and historically significant exceptions. His tone was measured, his delivery steady, and his scripts meticulously vetted. In an era when television was quickly overtaking print and radio as the dominant medium for news, Cronkite’s reliability made him a fixture in American households.2

The Kennedy Assassination and National Grief

Cronkite’s coverage of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, became an indelible moment in American collective memory. His composure while delivering the harrowing news, even as he momentarily removed his glasses and visibly choked up, struck a balance between human vulnerability and professional restraint. “From Dallas, Texas, the flash—apparently official: President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time,” he intoned. “2 o’clock Eastern Standard Time, some 38 minutes ago.”3

That moment became emblematic of how Americans experienced shared trauma through a trusted source. Cronkite was not merely reporting events; he was mediating national grief. Polls taken in the years following consistently placed him among the most respected public figures in the country, and his trustworthiness became a cultural touchstone.4

Vietnam and the Limits of Objectivity

Perhaps the most consequential moment in Cronkite’s career—and arguably in American broadcast journalism—came in 1968 following the Tet Offensive. After a two-week fact-finding mission to Vietnam, Cronkite broke with his usual neutrality during a special report aired on February 27. He concluded: “It seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate.”5

President Lyndon B. Johnson, upon hearing Cronkite’s report, is reputed to have remarked, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.”6 Whether apocryphal or not, the statement captured the weight of Cronkite’s influence. His shift in tone was not an abandonment of journalistic principle, but rather a rare moment of editorial judgment grounded in empirical observation. By choosing to contextualize rather than merely report, Cronkite acted on what he saw as a moral imperative—one that ultimately reshaped public opinion about the war.

Moon Landings and the Celebration of Knowledge

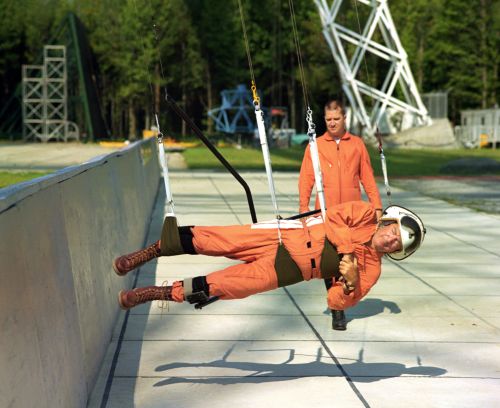

In contrast to the grimness of Vietnam and assassinations, Cronkite also provided narration for one of humanity’s most uplifting achievements: the Apollo 11 moon landing in July 1969. His giddy excitement—clapping his hands and exclaiming, “Oh, boy!”—was a departure from his usual demeanor, yet it only enhanced his credibility. It demonstrated that Cronkite was not merely a newsreader, but someone who deeply cared about the events he was covering.7

His reverence for science, reason, and exploration mirrored mid-century American ideals. In this sense, Cronkite served not only as a trusted messenger but also as an emblem of national aspiration. He made Americans feel like participants in history rather than passive observers.

Watergate and the Triumph of Investigative Journalism

Though not the primary investigative reporter on the Watergate story—that credit goes to The Washington Post’s Woodward and Bernstein—Cronkite played a crucial role in legitimizing and amplifying the scandal on national television. In doing so, he helped usher complex political reportage into the public consciousness. His coverage emphasized constitutional accountability rather than partisan retribution, thus reinforcing public trust in the institutional role of journalism.8

By the time Richard Nixon resigned in 1974, the American public had become accustomed to looking to Cronkite for clarity amid chaos. His coverage helped demystify political processes for the average citizen, offering not sensationalism, but sober analysis grounded in constitutional norms.

The Most Trusted Man in America

A 1972 poll by the Roper Organization found Cronkite to be the most trusted man in America—more trusted than the president, members of Congress, or any other public figure.9 His final sign-off in 1981—“That’s the way it is”—had become not just a catchphrase, but a cultural imprimatur of reliability. In an age of expanding media saturation, Cronkite remained a singular figure whose voice cut through the noise with calm authority.

This trust was not accidental. It was cultivated through decades of consistency, impartiality, and a willingness to break from neutrality only when the moral or democratic stakes demanded it. Cronkite’s ethos was anchored in the belief that journalism had a civic responsibility—a notion increasingly rare in the fragmented media landscape of the 21st century.

Legacy and Lessons

The post-Cronkite era has seen a proliferation of opinion-driven media, 24-hour news cycles, and the erosion of public trust in journalism. Pew Research Center data from the 2000s onward consistently shows declining confidence in the press across political lines.10 In such a climate, Cronkite’s legacy offers both inspiration and a cautionary tale. His model of journalism—fact-based, civic-minded, and emotionally grounded—remains a gold standard against which modern journalism can be measured.

Cronkite himself recognized the changing tides. In retirement, he lamented the rise of infotainment and the decline of investigative reporting. Yet he remained hopeful, believing in journalism’s capacity to inform and uplift when practiced with integrity.

Conclusion

Walter Cronkite became the most trusted man in America not because he sought trust, but because he earned it through consistency, courage, and compassion. In times of national triumph and tragedy, he gave voice to the conscience of the country. His life and career demonstrate that trust in media is not merely a function of style or charisma, but of substance—an enduring reminder that journalism, at its best, can be both a mirror and a moral compass for society.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Douglas Brinkley, Cronkite (New York: Harper, 2012), 85.

- Michael Schudson, Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers (New York: Basic Books, 1978), 183.

- CBS News Archives, “Walter Cronkite Announces Death of JFK,” CBS, November 22, 1963.

- Gallup, “Most Trusted American Figures,” 1965–1975 Surveys.

- Walter Cronkite, “Report from Vietnam,” CBS News Special Report, February 27, 1968.

- Theodore H. White, The Making of the President 1968 (New York: Atheneum Publishers, 1969), 353.

- CBS News, “Apollo 11 Coverage,” July 20, 1969.

- David Halberstam, The Powers That Be (New York: Knopf, 1979), 704.

- Roper Organization, Public Opinion Poll, 1972.

- Pew Research Center, “Public Trust in Media 1956–2020,” accessed May 2025.

Bibliography

- Brinkley, Douglas. Cronkite. New York: Harper, 2012.

- CBS News Archives. “Walter Cronkite Announces Death of JFK.” CBS, November 22, 1963.

- CBS News. “Apollo 11 Coverage.” July 20, 1969.

- Cronkite, Walter. “Report from Vietnam.” CBS News Special Report. February 27, 1968.

- Gallup. “Most Trusted American Figures.” Surveys, 1965–1975.

- Halberstam, David. The Powers That Be. New York: Knopf, 1979.

- Pew Research Center. “Public Trust in Media 1956–2020.” Accessed May 2025.

- Roper Organization. Public Opinion Poll, 1972.

- Schudson, Michael. Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers. New York: Basic Books, 1978.

- White, Theodore H. The Making of the President 1968. New York: Atheneum Publishers, 1969.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.