Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

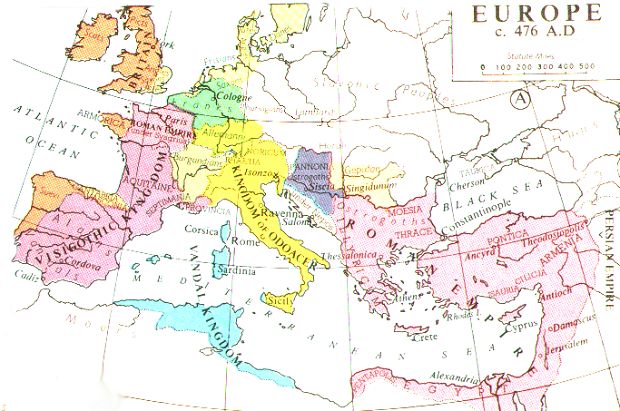

The Fall of Rome or the Fall of the Roman Empire refers to the defeat and sacking of the capital of the Western Roman Empire in 476 C.E. This brought approximately 1200 years of Roman domination in Western Europe to its end. The actual term, “the fall of Rome” was not coined until the eighteenth century. There are numerous theories as to why Rome “fell.” The city was first sacked in 410 C.E. by the Visigoths, led by Alaric I. Then, on September 4, 476, Odoacer, a Germanic chief, engineered the abdication of the last emperor in the West, Romulus Augustus. The Fall of Rome was a defining moment in the history of Western Europe. It led to the Church emerging, under the Popes, as the dominant authority and to the creation of a feudal society. The Eastern Empire, with its capital at Constantinople, or New Rome, survived until 1453.

Some European nations saw themselves as so indebted to the legacy of the Roman Empire, whose legacy continued to inform much of European culture and its social-political systems, that as they gained their own Empires in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they were fascinated to understand what had led to Rome’s defeat. Perhaps lessons could be learned that would aid the survival of the European empires, or perhaps universal lessons could be developed that explain why great empires rise and fall. Such historians as Edward Gibbon and Arnold Toynbee especially have speculated on this issue. Was Rome’s fall due to loss of virtue, to sexual and material decadence, or to misrule?

Much of the history of West Europe post-476 C.E. has been an attempt to revive the legacy of Rome. This lay behind the creation, in 800 C.E., of the Holy Roman Empire. This also lies behind such imperial projects as those of the British, Napoleon Bonaparte of France and also of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. Consequently, the Fall of Rome can be understood as an iconic moment in European history. On the one hand, it evokes a sense of loss: on the other, it resulted in freedom for those kingdoms that had been colonized by Rome. Yet Ancient Rome actually lives on in the European mind, as a symbol of “order and justice, freedom and faith, beauty and occidental humanity” [1]. Rome’s enduring significance in cultural, legal, administrative and literary terms remains so important that intrigue about how and why she declined and fell is unlikely to diminish. No single theory has yet dominated the academic world.

The Fall of the Western Roman Empire (395–476 C.E.)

The year 476 is generally accepted as the end of the Western Roman Empire. Before this, in June 474, Julius Nepos became Western Emperor. The Master of Soldiers Orestes revolted and put his son Romulus Augustus on the throne and Nepos fled back to his princedom in Dalmatia in August 475. Romulus however, was not recognized by the Eastern Emperor Zeno and so was technically a usurper, Nepos still being the legal Western Emperor.

The Germanic Heruli, under their chieftain Odoacer, were refused land by Orestes, whom they killed. They then deposed Romulus Augustus in August 476. Odoacer then sent the Imperial Regalia back to the emperor Zeno, and the Roman Senate informed Zeno that he was now the Emperor of the whole empire. Zeno soon received two deputations. One was from Odoacer requesting that his control of Italy be formally recognized by the Empire, in which he would acknowledge Zeno’s supremacy. The other deputation was from Nepos, asking for support to regain the throne. Zeno granted Odoacer the title Patrician.

Odoacer and the Roman Senate were told to take Nepos back. However, Nepos never returned from Dalmatia, even though Odoacer issued coins in his name. Upon Nepos’ death in 480, Odoacer annexed Dalmatia to his kingdom.

The next seven decades played out as aftermath. Theodoric the Great as King of the Ostrogoths, couched his legitimacy in diplomatic terms as being the representative of the Emperor of the East. Consuls were appointed regularly through his reign: a formula for the consular appointment is provided in Cassiodorus’s Book VI. The post of consul was last filled in the west by Theodoric’s successor, Athalaric, until he died in 534. Ironically the Gothic War in Italy, which was meant as the reconquest of a lost province for the Emperor of the East and a re-establishment of the continuity of power, actually caused more damage and cut more ties of continuity with Antiquity than the attempts of Theodoric and his minister Cassiodorus to meld Roman and Gothic culture within a Roman form.

In essence, the “fall” of the Roman Empire to a contemporary depended a great deal on where they were and their status in the world. On the great villas of the Italian Campagna, the seasons rolled on without a hitch. The local overseer may have been representing an Ostrogoth, then a Lombard duke, then a Christian bishop, but the rhythm of life and the horizons of the imagined world remained the same. Even in the decayed cities of Italy consuls were still elected. In Auvergne, at Clermont, the Gallo-Roman poet and diplomat Sidonius Apollinaris, bishop of Clermont, realized that the local “fall of Rome” came in 475, with the fall of the city to the Visigoth Euric. In the north of Gaul, a Roman kingdom existed for some years and the Franks had their links to the Roman administration and military as well. In Hispania the last Arian Visigothic king Liuvigild considered himself the heir of Rome. Hispania Baetica was still essentially Roman when the Moors came in 711, but in the northwest, the invasion of the Suevi broke the last frail links with Roman culture in 409. In Aquitania and Provence, cities like Arles were not abandoned, but Roman culture in Britain collapsed in waves of violence after the last legions evacuated: the final legionary probably left Britain in 409.

Term

The decline of the Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire, is a historical term of periodization which describes the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. The term was first used in the eighteenth century by Edward Gibbon in his famous study The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, but he was neither the first nor the last to speculate on why and when the Empire collapsed. It remains one of the greatest historical questions, and has a tradition rich in scholarly interest. In 1984, German professor Alexander Demandt published a collection of 210 theories on why Rome fell[2].

The traditional date of the fall of the Roman Empire is September 4, 476 when Romulus Augustus, the Emperor of the Western Roman Empire was deposed. However, many historians question this date, and use other benchmarks to describe the “Fall.” Why the Empire fell seems to be relevant to every new generation, and a seemingly endless supply of theories are discussed on why it happened, or if it happened at all.

“Declining Empire” Theories

Overview

Generally, these theories argue that the Roman Empire might have survived indefinitely if not for some combination of circumstances which led to its premature fall. Some historians in this camp believe that Rome “brought it on themselves,” that is, ensured their own collapse by either misguided policies or degradation of character.

Vegetius

The Roman military expert and historian Flavius Vegetius Renatus, author of De Re Militari[3] written in the year 390 C.E., theorized, and has recently been supported by the historian Arthur Ferrill, that the Roman Empire declined and fell due to increasing contact with barbarians and a consequent “barbarization,” as well as a surge in decadence. The resulting lethargy, complacency and ill-discipline among the legions made it primarily a military issue.

Gibbon

Edward Gibbon famously placed the blame on a loss of civic virtue among the Roman citizens. They gradually outsourced their duties to defend the Empire to barbarian mercenaries who eventually turned on them. Gibbon considered that Christianity had contributed to this, making the populace less interested in the worldly here-and-now and more willing to wait for the rewards of heaven. “[T]he decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness. Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the causes of destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest; and as soon as time or accident had removed the artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight,” he wrote.

Gibbon’s work is notable for its erratic, but exhaustively documented, notes and research. Interestingly, since he was writing two centuries ago, Gibbon also mentioned the climate, while reserving naming it as a cause of the decline, saying “the climate (whatsoever may be its influence) was no longer the same.” While judging the loss of civic virtue and the rise of Christianity to be a lethal combination, Gibbon did find other factors possibly contributing in the decline.

Richta

On the other hand, some historians have argued that the collapse of Rome was outside the Romans’ control. Radovan Richta holds that technology drives history. Thus, the invention of the horseshoe in Germania in the 200s would alter the military equation of pax romana, as would a borrowing of the compass from its inventors in China in the 300s.

This theory however ignores one of the Roman’s great strengths — adapting to their enemies’ technology and tactics. (For instance, Rome had no navy when Carthage arose as a rival power based on its superb navy; in a few generations the Romans went from no navy, to a poor navy, to a navy sufficient to defeat the Carthaginians in the Third Punic War 149-146 B.C.E..) It also ignores the tactics the Romans adapted to cope with superior weaponry, as when Hannibal’s elephants were negated by shifting the infantry formations to avoid their charge. Finally, the theory also ignores the fact that German horsemen served in enormous numbers as foederati in the Roman military as well as the fact that the majority of barbarians that the Romans fought in the third through sixth centuries fought as infantrymen.

Bryan Ward-Perkins

Bryan Ward-Perkins’ The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (2005) makes the more traditional and nuanced argument that the empire’s demise was brought about through a vicious cycle of political instability, foreign invasion, and reduced tax revenue. Essentially, invasions caused long-term damage to the provincial tax base, which lessened the Empire’s medium to long-term ability to pay and equip the legions, with predictable results. Likewise, constant invasions encouraged provincial rebellion as self-help, further depleting Imperial resources. Contrary to the trend among some historians of the “there was no fall” school, who view the fall of Rome as not necessarily a “bad thing” for the people involved, Ward-Perkins argues that in many parts of the former Empire the archaeological record indicates that the collapse was truly a disaster.

Ward-Perkins’ theory, much like Bury’s, and Heather’s, identifies a series of cyclic events that came together to cause a definite decline and fall. The primary difference in his work and Bury’s, was that like Heather, they had access to archaeological records which strongly supported the stance that the fall was a genuine disaster for millions.

John Bagnall Bury

John Bagnall Bury’s “History of the Later Roman Empire” gives a multi-factored theory for the Fall of the Western Empire. He presents the classic “Christianity vs. pagan” theory, and debunks it, citing the relative success of the Eastern Empire, which was far more Christian. He then examines Gibbon’s “theory of moral decay,” and without insulting Gibbon, finds that too simplistic, though a partial answer. Bury essentially presents what he called the “modern” theory, which he implicitly endorses, a combination of factors, primarily, (quoting directly from Bury:

“The Empire had come to depend on the enrollment of barbarians, in large numbers, in the army, and that it was necessary to render the service attractive to them by the prospect of power and wealth. This was, of course, a consequence of the decline in military spirit, and of depopulation, in the old civilised Mediterranean countries. The Germans in high command had been useful, but the dangers involved in the policy had been shown in the cases of Merobaudes and Arbogastes. Yet this policy need not have led to the dismemberment of the Empire, and but for that series of chances its western provinces would not have been converted, as and when they were, into German kingdoms. It may be said that a German penetration of western Europe must ultimately have come about. But even if that were certain, it might have happened in another way, at a later time, more gradually, and with less violence. The point of the present contention is that Rome’s loss of her provinces in the fifth century was not an “inevitable effect of any of those features which have been rightly or wrongly described as causes or consequences of her general ‘decline.'” The central fact that Rome could not dispense with the help of barbarians for her wars (gentium barbararum auxilio indigemus) may be held to be the cause of her calamities, but it was a weakness which might have continued to be far short of fatal but for the sequence of contingencies pointed out above.”[4]

In short, Bury held that a number of contingencies arose simultaneously: economic decline, Germanic expansion, depopulation of Italy, dependency on German foederati for the military, Stilcho’s disastrous (though Bury believed unknowing) treason, loss of martial vigor, Aetius’ murder, the lack of any leader to replace Aetius — a series of misfortunes which proved catastrophic in combination.

Bury noted that Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” was “amazing” in its research and detail. Bury’s main differences from Gibbon lay in his interpretation of fact, rather than any dispute of fact. He made clear that he felt that Gibbon’s conclusions as to the “moral decay” were viable — but not complete. Bury’s judgement was that:

“the gradual collapse of the Roman power …was the consequence of a series of contingent events. No general causes can be assigned that made it inevitable.”

It is his theory that the decline and ultimate fall of Rome was not pre-ordained, but was brought on by contingent events, each of them separately endurable, but together and in conjunction ultimately destructive.

Peter Heather

Peter Heather offers an alternate theory of the decline of the Roman Empire in the work The Fall of the Roman Empire (2005). Heather maintains the Roman imperial system with its sometimes violent imperial transitions and problematic communications notwithstanding, was in fairly good shape during the first, second, and part of the third centuries C.E. According to Heather, the first real indication of trouble was the emergence in Iran of the Sassaniad Persian empire (226-651). Heather says:

“The Sassanids were sufficiently powerful and internally cohesive to push back Roman legions from the Euphrates and from much of Armenia and southeast Turkey. Much as modern readers tend to think of the “Huns” as the nemesis of the Roman Empire, for the entire period under discussion it was the Persians who held the attention and concern of Rome and Constantinople. Indeed, 20-25% of the military might of the Roman Army was addressing the Persian threat from the late third century onward … and upwards of 40% of the troops under the Eastern Emperors.” [5]

Heather goes on to state — and he is confirmed by Gibbon and Bury — that it took the Roman Empire about half a century to cope with the Sassanid threat, which it did by stripping the western provincial towns and cities of their regional taxation income. The resulting expansion of military forces in the Middle East was finally successful in stabilizing the frontiers with the Sassanids, but the reduction of real income in the provinces of the Empire led to two trends which were to have an extraordinarily negative long term impact. Firstly, the incentive for local officials to spend their time and money in the development of local infrastructure disappeared. Public buildings from the 4th century onward tended to be much more modest and funded from central budgets, as the regional taxes had dried up. Secondly, Heather says “the landowning provincial literati now shifted their attention to where the money was … away from provincial and local politics to the imperial bureaucracies.”

Heather then argues that after the fourth century, the Germanic invasions, Huns, Stilcho, Aetius, and his murder, all led to the final fall. But his theory is both modern and relevent in that he disputes Gibbon’s contention that Christianity and moral decay led to the decline, and places its origin squarely on outside military factors, starting with the Great Sassanids. Like Bury, he does not believe the fall was inevitable, but rather a series of events which came together to shatter the Empire. He differs from Bury, however, in placing the onset of those events far earlier in the Empire’s time-line, with the Sassanid rise.

Heather’s theory is extremely important because it has the advantages of modern archaeological findings, weather and climatic data, and other information unavailable to earlier historians.

“Doomed from the Start” Theories

In contrast with the “declining empire” theories, historians Arnold J. Toynbee and James Burke argue that the Roman Empire itself was a rotten system from its inception, and that the entire Imperial era was one of steady decay of its institutions. In their view, the Empire could never have lasted. The Romans had no budgetary system. The Empire relied on booty from conquered territories (this source of revenue ending, of course, with the end of Roman territorial expansion) or on a pattern of tax collection that drove small-scale farmers into destitution (and onto a dole that required even more exactions upon those who could not escape taxation), or into dependency upon a landed élite exempt from taxation. Meanwhile the costs of military defense and the pomp of Emperors continued. Financial needs continued to increase, but the means of meeting them steadily eroded. In a somewhat similar strain, Joseph Tainter argues that the Empire’s collapse was caused by a diminishing marginal return on investment in complexity, a limitation to which most complex societies are eventually subject.

“There Was No Fall” Theories

Overview

Lastly, some historians take issue with the use of the term “fall” (and may or may not agree with “decline”). They note that the transfer of power from a central imperial bureaucracy to more local authorities was both gradual and typically scarcely noticeable to the average citizen.

Henri Pirenne

Belgian historian Henri Pirenne published the “Pirenne Thesis” in the 1920s which remains influential to this day. It holds that the Empire continued, in some form, up until the time of the Arab conquests in the seventh century,[6] which disrupted Mediterranean trade routes, leading to a decline in the European economy. This theory stipulates the rise of the Frankish Realm in Europe as a continuation of the Roman Empire, and thus legitimizes the crowning of Charlemagne as the first Holy Roman Emperor as a continuation of the Imperial Roman State. Some modern historians, such as Michael Grant, subscribe to this theory at least in part – Grant lists Charles Martel’s victory at the Battle of Tours halting the Islamic conquest era and saving Europe as a macrohistorical event in the history of Rome.

However, some critics maintain the “Pirenne Thesis” erred in claiming the Carolingian Realm as a Roman State, and mainly dealt with the Islamic conquests and their effect on the Byzantine or Eastern Empire.

“Late Antiquity”

Historians of Late Antiquity, a field pioneered by Peter Brown, have turned away from the idea that the Roman Empire “fell.” They see a “transformation” occurring over centuries, with the roots of Medieval culture contained in Roman culture and focus on the continuities between the classical and Medieval worlds. Thus, it was a gradual process with no clear break.

Despite the title, in The Fall of the Roman Empire (2005), Peter Heather argues for an interpretation similar to Brown’s, of a logical progression from central Roman power to local, Romanized “barbarian” kingdoms spurred by two centuries of contact (and conflict) with Germanic tribes, the Huns, and the Persians. However, unlike Brown, Heather sees the role of the Barbarians as the most significant factor; without their intervention he believes the western Roman Empire would have persisted in some form. As discussed above, Heather’s theory is also similiar to Bury’s in that he believes the decline was not inevitable, but arose out of a series of events which together brought the decline, and fall.

Historiography

Historiographically, the primary issue historians have looked at when analyzing any theory is the continued existence of the Eastern Empire or Byzantine Empire, which lasted for about a thousand years after the fall of the West. For example, Gibbon implicates Christianity in the fall of the Western Empire, yet the eastern half of the Empire, which was even more Christian than the west in geographic extent, fervor, penetration and sheer numbers continued on for a thousand years afterwards (although Gibbon did not consider the Eastern Empire to be much of a success). As another example, environmental or weather changes impacted the east as much as the west, yet the east did not “fall.”

Theories will sometimes reflect the eras in which they are developed. Gibbon’s criticism of Christianity reflects the values of the Enlightenment; his ideas on the decline in martial vigor could have been interpreted by some as a warning to the growing British Empire. In the nineteenth century socialist and anti-socialist theorists tended to blame decadence and other political problems. More recently, environmental concerns have become popular, with deforestation and soil erosion proposed as major factors, and epidemics such as early cases of bubonic plague, resulting in destabilizing population decreases, and malaria also cited. Ramsay MacMullen in the 1980s suggested it was due to political corruption. Ideas about transformation with no distinct fall owe much to postmodern thought, which rejects periodization concepts (see metanarrative). What is not new are attempts to diagnose Rome’s particular problems, with Juvenal in the early second century, at the height of Roman power, criticizing the peoples’ obsession with “bread and circuses” and rulers seeking only to gratify these obsessions.

One of the primary reasons for the sheer number of theories is the notable lack of surviving evidence from the fourth and fifth centuries. For example there are so few records of an economic nature it is difficult to arrive at even a generalization of how the economic conditions were. Thus, historians must quickly depart from available evidence and comment based on how things ought to have worked, or based on evidence from previous and later periods, or simply based on inductive reasoning. As in any field where available evidence is sparse, the historian’s ability to imagine the fourth and fifth centuries will play as important a part in shaping our understanding as the available evidence, and thus be open for endless interpretation.

Appendix

Notes

- This is a citation referring to Rome’s fall to the Allies of World War II from the German Propanganda Archive, giving a Nazi perpective, “Rom,” Berlin Rom Tokio. Monatschrift für die Vertiefung der kulturellen Beziehungen der Völker des weltpolitischen Dreiecks, VI (June, 1944), 2-3, Randall Bytwerk, German Propaganda Archive, [1]. retrieved 22-01-2007

- Alexander Demandt: 210 Theories, from Crooked Timber weblog entry August 25, 2003. Retrieved June 2005.

- The Military Institutions of the Romans, Translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke. [2]. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Chapter on Attila, from J.B. Bury’s History of the Later Roman Empire. [3]. Roman Texts, Univeristy of Chicago. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- Peter Heather [4]. anglosphere.com Fall of the Roman Empire: A New Theory discussion. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- Mohammed and Charlemagne. by Henri Pirenne. [5] Review and summary. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

References

- Brown, Peter. The World of Late Antiquity AD 150-750. (Library of World Civilization) New York: W.W. Norton, 1989.

- Bury, J.B., History of the Later Roman Empire. Macmillan & Co, Ltd. 1923. (text is in the public domain)

- Cameron, Averil, and Peter Garnsey, (Eds). The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13: The Late Empire, AD 337-425. Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998

- Demandt, Alexander. Der Fall Roms: Die Auflösung des römischen Reiches im Urteil der Nachwelt. München: Beck, 1984. (in German)

- Flavius. Flavius Vegetius Renatus, De Re Militari The Military Institutions of the Romans, Translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke. [6]. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Geary, Patrick J. Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World. Oxford Univ. Press, 1988. ISBN0195044584 survey of Merovingian world.

- Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. NY: Random House/Modern Library, reprint 2005.

Originally published by New World Encyclopedia, 03.05.2017, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.