Roman accounts exhibited few illusions about the level of resistance to their rule.

By Dr. Neville Morley

Professor in Classics and Ancient History

University of Exeter

Introduction

Robbers of the world, now that the earth is insufficient for their all-devastating hands they probe even the sea; if their enemy is rich, they are greedy; if he is poor, they thirst for dominion; neither east nor west has satisfied them; alone of mankind they are equally covetous of poverty and wealth. robbery, slaughter and plunder they falsely name empire; they make a desert and they call it peace.

Tacitus, Agricola, 30.4

Different interpretations of the dynamics of Roman conquest have been deployed to legitimise modern empire-building as just, defensive or accidental, and just as often cited in condemnations of overseas aggression or gunboat diplomacy.1 However, with the exception of Fascist propaganda presenting Roman domination of the Mediterranean as the template and justification for a new Italian imperialism, and Hitler’s avowed admiration for their aggression (‘In every peace treaty, the next war is already built in. That is Rome! That is true statesmanship!’), Roman conquests were not proposed or taken as models for actual modern practice.2 The manner in which the Roman Empire was ruled was a quite different matter; indeed, Roman conquests were frequently excused as the necessary means to the establishment of peace and civilisation across Europe, and modern imperialism justified because it created the possibility of equalling Rome’s achievement as a ruler of other nations in other regions of the world. Rome’s exemplary status as an empire was based above all on its longevity and the absence of serious internal opposition or conflict, and this was attributed to its benevolent and beneficent impact on the areas it had conquered.3 As the English historian J.R. Seeley put it, ‘Imperialism, introducing system and unity, gave the Roman world in the first place internal tranquillity.’4

This theme was especially popular in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century British commentaries on empire: ‘its imperial system, alike in its differences and similarities, lights up our own Empire, for example in India, at every turn’.5 The example was not taken as universally relevant; in contrast to the British Dominions, the Romans had not succeeded in raising their subjects to point of self-government, not least because their empire had focused on the conquest and rule of already-occupied regions rather than the settlement of (supposedly) uninhabited areas. ‘They gave organization, laws, institutions, language, roads and buildings, but they did not give birth to and rear from subordination to equality young peoples of their own Roman race.’6 In India, and later Africa, however, the British confronted the same problem of ruling an uncivilised foreign population, and could hope to learn from Rome’s achievements. As Charles Trevelyan suggested in 1838, ‘acquisitions made by superiority in war were consolidated by superiority in peace; and the remembrance of the original violence was lost in that of the benefits which resulted from it… The Indians will, I hope, soon stand in the same position towards us in which we once stood towards the Romans.’7 Roman imperialism was justified by its results, and the British could hope for the same, although for the moment, with regard to their policy towards the natives, ‘British Imperialism has, in so far as the indigenous races of Asia and Africa are concerned, been a failure.’8 After all, the imperial rulers shared the same ideals:

The success of the British, like that of the Roman administration in securing peace and good order, has been due, not merely to a sense of the interest every government has in maintaining conditions which, because favourable to industry are favourable also to revenue, but also to the high ideal of the duties of a rule which both nations have set before themselves.9

These references to Roman rule constantly return to three crucial points: the establishment of order and peace, the integration of the conquered natives into the system, and the bringing of civilisation to primitive regions. For a number of these writers, the first of these is demonstrably the most important, both as the basis for future development and as an alibi for the undeniable disruption and destruction of conquest:

Those who watch India most impartially see that a vast trans-formation goes on there, but sometimes it produces a painful impression upon them; they see much destroyed, bad things and good things together; sometimes they doubt whether they see many good things called into existence. But they see one enormous improvement, under which we may fairly hope that all other improvements are potentially included, they see anarchy and plunder brought to an end and something like the immensa majestas Romanae pacis [the immense majesty of the Roman peace] established among two hundred and fifty millions of human beings.10

It is striking that even works which made use of Roman examples in order to attack British imperialism, such as J.M. Robertson’s Patriotism and Empire, failed to engage with the positive evaluation of Roman rule and its impact on the conquered territories under the Principate, but focused instead on the rapaciousness of the Republican conquerors and the role of empire in the decay of liberty in Rome itself.11 The establishment of order and civilisation across the empire is clearly not regarded as sufficient justification for imperialism – but its achievement does not appear to be disputed.

Modern studies of imperialism make some remarkably similar assumptions about the Roman Empire, offering a sharp contrast between the process of its acquisition and the system of imperial rule, and focusing on the success of the latter, demonstrated by its longevity. Michael Mann’s study of social power characterises this as the shift from an empire of domination to a territorial empire, emphasising that Rome ‘was one of the most successful conquering states in all history, but it was the most successful retainer of conquests’.12 Michael Doyle, meanwhile, coined the concept of the ‘Augustan threshold’ for the shift from violent conquest to benign and sustainable rule, and applied this idea more widely as an explanation for the failures of the Spanish and the first English overseas empires: ‘The root cause of the collapse of the English empire in America was England’s failure to cross the Augustan Threshold.’13 Both stress the importance of stability and order, and, above all, the integration of local elites into the imperial state for Rome’s achievement.

These ideas are echoed in more popular contemporary discussions; indeed, it is clear that they underpin most of the arguments that present ‘empire’, in the form of United States hegemony, as a desirable global future. Deepak Lal’s account talks in general terms of the role played by empires in quelling international anarchy and offering ‘the essential public good of order’, bureaucracy, law, market prices and predictable human relations over a wide area, all at a reasonable cost; the only example cited, besides the United States as a potential imperial power, is Rome.14 Other writers are prepared to allow a positive case for Britain as well:

Throughout history, peace and stability have been a major benefit of empires. In fact, pax romana in Latin means the Roman peace, or the stability brought about by the Roman Empire. Rome’s power was so overwhelming that no one could challenge it successfully for hundreds of years. The result was stability within the Roman Empire. Where Rome conquered, peace, law, order, education, a common language, and much else followed. That was true of the British Empire (pax Britannica) too. So it is with the United States today.15

This impression of the essential benevolence and positive consequences of Roman rule is deep-seated; opponents of modern imperialism generally question its appropriateness for a contemporary context rather than dispute its historical accuracy. And yet the Roman sources themselves raised questions about whether the empire’s longevity was due to its enlightened administration rather than to the efficiency of its systems of control and coercion: examples include the words which Tacitus put into the mouth of the (otherwise unknown) British chieftain Calgacus at the end of the first century CE, quoted at the beginning of this chapter, or the unselfconscious menace in the account of his achievements left by the emperor who gave his name to the ‘Augustan threshold’: ‘When foreign peoples could safely be pardoned, I preferred to preserve rather than to exterminate them’ (Augustus, Res Gestae, 3.2).

Pacification

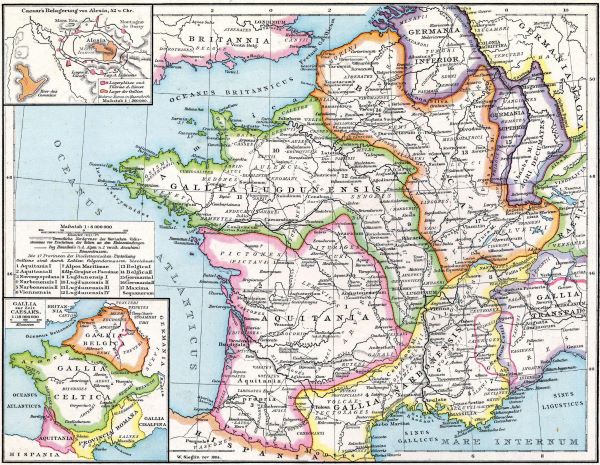

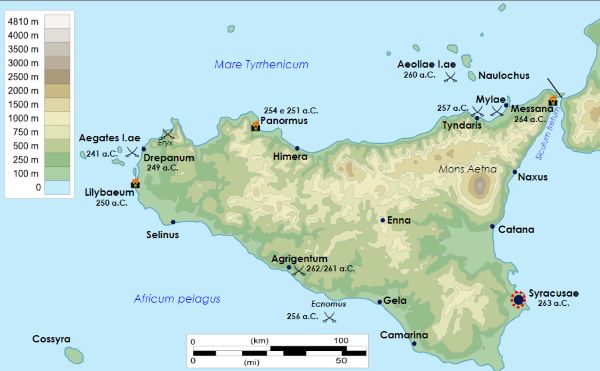

In the Republican period, Roman accounts exhibited few illusions about the level of resistance to their rule and the necessity of continued force to subdue most of the regions they controlled, for a considerable time after conquest. In relatively ‘civilised’ areas with well-established city-state systems, such as Greece and Asia Minor, the main concern was that individual cities might seek to change sides or revolt when Rome was threatened by an enemy like the Macedonians or Parthians. When he represented the people and cities of Sicily in court against their former governor Verres, Cicero took great pains to insist on the province’s long-standing loyalty to Rome, and still could not conceal the fact that this loyalty had never been complete or unquestioning: ‘once the various states in the island had embraced our friendship, they never thereafter seceded from it; and most of them, and those the most notable, remained our firm friends without interruption’ (Against Verres, II.2.2). At the other end of the spectrum, in a region like Gaul, there was constant attritional warfare against different tribal groups; Caesar spent almost all of his time there dealing with a succession of revolts against Roman power, and in less than ten years was said to have seized 800 settlements and sold over 1 million captives into slavery (Plutarch, Caesar, 15.5). Many provinces offered a mixture of the two situations: untrustworthy and opportunistic ‘allies’, and defiant opponents. Arriving in Cilicia in 51 BCE as its new governor amid rumours that a large Parthian force had crossed the Euphrates and was menacing the Roman provinces, Cicero wrote to the senate of his concern that the allied cities were wavering in expectation of a change in the established order in the region; there was little hope of raising troops through a local levy because they were either feeble or ‘so estranged from us that it seems as though we ought neither to expect anything of them nor to entrust anything to their keeping’ (Letters to his Friends, 15.1). When the Parthian attack failed to materialise, he embarked on military action against a hostile tribe called the Amanienses, burning their fortified posts, and besieged the town of Pindenissum, a stronghold of the Free Cilicians ‘which has been at war as long as people remember’; the troops sacked the town, while Cicero received 120,000 sesterces from selling the prisoners (Letters to Atticus, 5.20.5). He took hostages from a neighbouring, equally hostile tribe, and arranged for his army to be billeted for the winter on newly-captured and recalcitrant villages (Letters to his Friends, 15.4.10). For all of Cicero’s self-congratulation, there was clearly little expectation that the pacification of Cilicia would be concluded in the near future.

There were clear structural reasons why the Roman Republic could be open about the existence of sustained resistance to its rule; while one governor might declare that a province had been subdued as a result of his victories, his successor would have no compunction in contradicting that claim in order to obtain the troops and resources needed to deal with a continuing insurgency. Of course, the precise nature of this new emergency might be questioned; the main concern of most governors of a province like Spain or Cilicia was to seek out an opportunity for military glory on their own account, and a triumph might be awarded for actions that were little more than a raid on a hostile tribe. The two centuries which it took to subdue the Iberian peninsula, tying up 20,000–25,000 troops on a permanent basis, can be attributed as much to the incompetence, heavy-handedness and provocative behaviour of Roman commanders, and the absence of any coherent plan for pacification, as to the qualities or temperament of the natives.16

Roman treatment of opposition was violent and destructive, with massacres, mass enslavement and the destruction of settlements – regardless of their beauty or historical significance, as in the sack of Corinth in 146 BCE or of Athens in 86 BCE (although in the latter case, the Roman commander, Sulla, prohibited the burning of the city). Rome’s subjects had a clear idea of the consequences of rebellion and, nevertheless, some resented Roman rule sufficiently to ally themselves with powers like Macedonia or Mithridates of Pontus. In the west, the deterrent effect of the Roman treatment of defeated rebels was perhaps reduced by the fact that they could behave like that even when peace had been negotiated. On two different occasions in Spain, Roman commanders promised to resettle a tribe on fertile land and then took the opportunity when they gathered together to massacre a significant number and sell the rest into slavery.17 On the first occasion, in 150 BCE, this triggered a widespread revolt that lasted over ten years until the Romans bribed some native envoys, sent to discuss peace terms, to assassinate their leader; on the second, it passed almost without comment.

Provinces were beaten into submission over decades, through the relentless and at times unpredictable application of military force, the gradual establishment of an infrastructure of camps and roads (built not for any peaceful purpose, but to facilitate troop movements in case of trouble) and the fear of subject communities that anything other than complete submission and cooperation might incur violent retribution. That is not to say that all Roman governors were treacherous war-mongerers looking for any opportunity to launch a punitive campaign, but a sufficiently large number of them were – and the Roman system encouraged rather than controlled this tendency – for it to be a permanent anxiety in all but the most peaceful of provinces. Even in Sicily, where the only military action after the Second Punic War had been the suppression of two large-scale slave revolts and where the governor relied on local levies rather than Roman troops, the threat of violent punitive action, examples of which continued to arrive from more distant parts of the empire, remained one of the crucial underpinnings of Roman domination.

The advent of the Principate and the establishment of autocratic rule under Augustus and his successors, following the civil wars of the first century BCE, brought Peace to the Empire. That was, at any rate, the declaration of the regime; its achievement was celebrated in the images on coinage, in literature and in programmatic monuments like the Augustan Altar of Peace (Ara Pacis) and the Temple of Peace constructed by Vespasian.18 It became a recurrent theme in descriptions of the Empire and praise of the emperor. According to the historian Velleius Paterculus, ‘the pax Augusta, which has spread to the regions of the east and of the west and to the bounds of the north and of the south, preserves every corner of the world safe from the fear of brigandage’ (2.126.3); the encyclopaedist Pliny the Elder uses the phrase immensa Romanae pacis maiestate, ‘the immense majesty of the Roman peace’, as a synonym for the Empire (Natural History, 27.1.1), while the Greek orator Aelius Aristides waxed lyrical about the achievements of Rome in the middle of the second century CE:

Wars, even if they once occurred, no longer seem real; on the contrary, stories about them are interpreted more as myths by the many who hear them. If anywhere an actual clash occurs along the border, as is only natural in the immensity of a great empire, because of the madness of the Getae or the misfortune of the Libyans or the wickedness of those around the Red Sea, who are unable to enjoy the blessings they have, then simply like myths, they themselves quickly pass and the stories about them. So great is your peace, though war was traditional among you.

Oration 26 ‘To Rome’, 70–1

It should not be assumed that what the emperors and their propagandists were celebrating was identical with modern conceptions of peace. Pax in this context stood above all for the absence of civil war and the establishment of concordia at the heart of the Empire; it legitimised the replacement of the Republic with the rule of a single man, as the geographer Strabo argued early in Tiberius’ reign:

It is indeed difficult to administer a vast empire unless it is turned over to one man, as to a father. In any event, the Romans and their allies have never lived and prospered in such peace and plenitude as Augustus afforded them, from the time that he assumed absolute authority; and now his son and successor Tiberius continues his legacy.

Geography, 6.4.2

Clearly the Empire was assumed to benefit from the absence of dissension amongst its conquerors and of freedom from the depredations of squabbling warlords, but the pax celebrated by the emperors as their gift to the world had a more direct relevance to the provinces: it stood also for successful conquest, the establishment of absolute Roman dominance.19 Augustus’ claim was that he had pacified, once and for all, the provinces of Spain, Gaul and Germany, as well as recovering provinces lost in the east and adding Egypt to the Empire (Res Gestae, 26–7). Vespasian’s Temple of Peace commemorated the crushing of the Jewish revolt, the sacking of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple. Peace and empire were inextricably entwined, with imperial rule justified on the grounds that it brought peace – whether Rome’s subjects wished for it or not – and peace defined as the absence of resistance. As Virgil’s nationalistic epic put it: ‘You, Roman, remember by your empire to rule the world’s people (for these will be your arts), to impose the practice of peace, to be sparing to the subjected and to beat down the defiant’ (Aeneid, 6.851–3).

It is easy to show that the positive image of the pax Romana, taken at face value by generations of modern historians, is at best optimistic; as the historian Tacitus put it, as part of his incisive critique of the monarchic regime, his history was ‘violent with peace’ (Histories, 1.2). It is abundantly clear from legal texts and other sources that neither banditry nor piracy were ever stamped out in the Empire; Roman control never extended effectively into mountainous regions, forests or deserts, from where unassimilated tribes and refugees from the Empire could launch raids into settled areas.20 Civil war was scarcely eradicated, as seen after the death of Nero with the Year of the Four Emperors in 69 CE. Moreover, there are sufficient hints and passing comments in the sources to identify 100 or more examples of uprisings or revolts in the first two centuries of the Principate, from food riots in the city of Rome to full-blown rebellions in Gaul, to say nothing of famous revolts like Boudicca’s uprising in Britain and the series of Jewish wars.21 The gap between official rhetoric in the capital and the reality on the ground was clear enough to a disaffected observer like Tacitus. However, it would be misleading to dismiss the former as mere falsehood. Most ideologies exhibit a problematic relationship to reality, without that necessarily reducing their effectiveness. This one effectively characterised all opposition to the imperial regime as disturbers of the peace and the enemies of civil society, denying all legitimacy to their motives; it may well have worked to legitimise Roman rule in those regions which were largely spared serious disruption; and in particular it shaped the behaviour of the Romans themselves.

The Republican system had been readily able to accept that the process of pacification needed a further dose of military intervention, with minimal discredit even to the previous general; a revolt against the benevolent rule of the emperors, however, was deeply embarrassing to the individual who claimed full credit for establishing world peace. Augustus declined to make any report to the Senate about the campaign he had to fight in Spain in 26–25 BCE, and in his account of his own achievements presented the war against Sextus Pompeius in Sicily as merely an action against pirates. Tiberius, faced with a serious revolt in Gaul (which, according to Tacitus, left hardly any community untouched), chose to ignore it officially until the fighting was concluded, and then claimed that ‘it would be undignified for emperors, whenever there was a commotion in one or two states, to quit the capital, the centre of all government’ (Tacitus, Annals, 3.47). Thirty years later, in making a plea for Gallic nobles to be admitted to the senate, Claudius could claim that ‘if you examine the whole of our wars, none was finished in a shorter time than that against the Gauls; from then on there has been continuous and loyal peace’ (Annals, 11.24). The emperors and their subordinates displayed a similar tendency to self-deception or excessive optimism in the conquest of new territory, declaring mission accomplished after one successful campaign and apparently being genuinely surprised by any subsequent trouble. The massacre of Varus’ legions in the Teutoberger Forest in 9 CE was a response to his attempts at collecting tribute and dispensing orders in the region of Germania; that is, treating it as a normal and fully pacified province and expecting its inhabitants to submit to his demands.

The natives were adapting themselves to orderly Roman ways and were becoming accustomed to holding markets and were meeting in peaceful assemblies. They had not, however, forgotten their ancestral habits, their native customs, their old life of independence or the power derived from weapons. Hence, so long as they were learning these customs gradually and by the way, one might say, under careful surveillance, they were not disturbed by the change in their way of life and were becoming different without knowing it. But when Quintilius Varus became governor in Germany and thus administered the affairs of those peoples, he strove to change them more rapidly.

Dio, 65.18.2–3

Resistance to Roman rule was generally presented as brigandage; that label stripped it of any legitimacy as a movement of protest, but it also offered the local commander a valid excuse for requesting reinforcements and resources, whereas admitting to the existence of a serious revolt would invariably be taken as a personal failure of the governor, since the alternative was to question the legitimacy of the entire imperial regime.

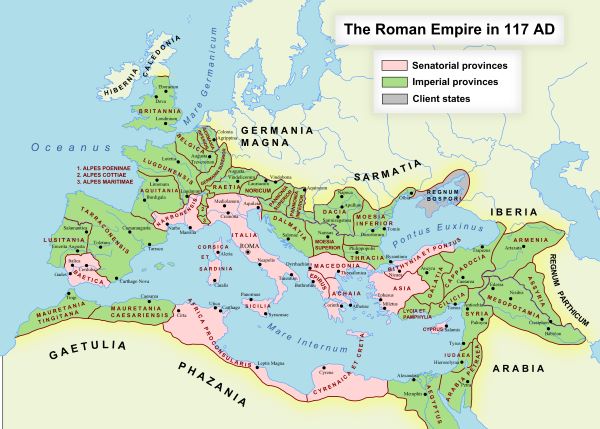

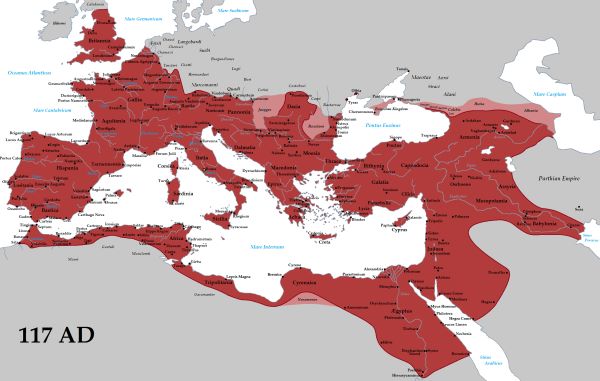

This fond belief in a rapid and irreversible progress from conquered territory to loyal province makes it difficult to discuss resistance to Roman rule under the Principate in any detail, since the sources scarcely discuss the subject. It is clear enough that the claims of Roman and Greek writers about the peacefulness of the empire cannot be taken at face value, let alone the belief of many modern historians that this absence of opposition or resistance can be attributed to the benevolence of Roman rule. However, the advent of the autocracy did lead to some significant changes in the Empire, besides an inability to admit to the possibility that anyone could conceivably resent Roman dominance. The rate of expansion slowed significantly. Augustus had advised his successor that the Empire should be kept within its existing boundaries (whether through fear or jealousy, as Tacitus suggested (Annals, 1.11), or for strategic reasons), and, while some emperors continued to pursue a policy of conquest, others preferred to consolidate territory or even, as in the case of Hadrian, to withdraw from a predecessor’s conquests.

Controlling the fairest parts of land and sea, they have on the whole tried to preserve their empire by diplomatic means rather than to extend their power without limit over poor and profitless barbarian tribes, some of whom I have seen negotiating at Rome in order to offer themselves as subjects. But the emperor would not receive them because they are useless to him.

Appian, Roman History, preface vii

The process that had begun in the later centuries of the republic, whereby military glory ceased to be an essential source of political power and legitimacy, continued; expansionism ceased to be taken for granted as a goal, and became a matter of policy debate.22 More importantly, the fierce competition for glory had largely ceased. Emperors had no contemporary rivals for status; they matched themselves against their predecessors or against an image of the ideal emperor, and so could be content with a single conquest in the course of their reign rather than year-on-year competitive slaughter. At the same time, it was essential for them to prevent the emergence of potential rivals, by strictly limiting the opportunities of others for glory: triumphs were reserved for members of the imperial family (victories won by others were assumed to be achieved in the name of the emperor), while generals out in the frontier regions were strongly discouraged from taking any significant action without authorisation, let alone embarking on substantial campaigns. Expansion thus became more methodical and controlled, even – up to a point – more rational; the frontiers tended to stabilise in marginal regions, between settled agricultural areas that could easily support the Roman military infrastructure and wilder, emptier areas of forest or desert that promised to be expensive and unrewarding to conquer.23

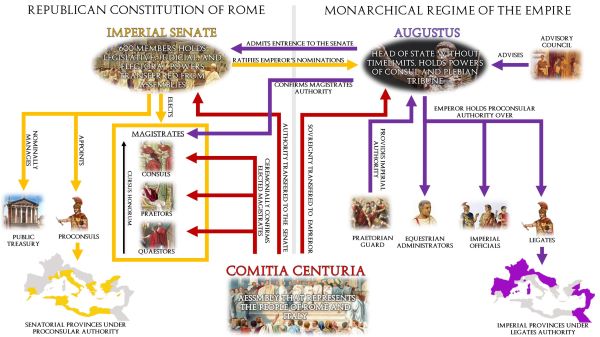

Increased stability in frontier regions was echoed elsewhere in the Empire. Augustus’ division of the provinces between those to be governed by senators, which involved no significant military activity, and those which remained under his direct control echoed the distribution of Roman forces and cemented tendencies already visible under the republic. Many regions – long-established and ‘civilised’ provinces like Achaea, Asia and Sicily, and the parts of Spain and Gaul longest in Roman hands – were assumed to be adequately pacified and far enough away from any significant enemy to risk leaving them without a substantial military presence. There is no evidence to support the idea that provinces were routinely and permanently disarmed; on the contrary, in the absence of a large body of Roman troops the governor would depend on recruiting soldiers locally to deal with any problems.24 In other words, Roman peace was enough of a reality that large areas of empire could be governed effectively without regular recourse to direct force, with not only the acquiescence but the active collaboration of at least some provincials in enforcing Roman dominance.

Collaboration and Urbanization

Indeed, Roman government would have been entirely impossible without such local assistance. As late as the second century CE, the Empire was run by just 150 elite administrators, one for every 400,000 provincials. In comparison, British India in the nineteenth century was governed by around 7,000 administrators, one for every 43,000 natives, while under the Song dynasty in China, in the twelfth century, there was one official for every 15,000 inhabitants.25 Of course, the Roman officials were supported by slaves and other assistants, but at the most these may have numbered 10,000, giving one representative of Roman power for every 6,000 of its subjects. The aims of Roman rule were strictly limited, focused on maintaining order and ensuring the continued flow of revenue, but even so it was impossible for such a small number of officials to manage all the day-to-day business of the control and exploitation of the provincials. Consideration of the geographical extent of the Empire and the effects of distance, in a preindustrial society where communications were limited to the speed of the fastest horse or most favourable winds and where the news of an emperor’s death might not reach more distant regions for weeks, leads to the same conclusion: Roman rule depended on the delegation of power to the local level, not only to Roman officials, who had broad freedom of action in most affairs, but to their native collaborators.26

Thus the expansion of the Empire in the central and eastern Mediterranean depended on the establishment of friendly relations with hundreds of cities, each one dominating its immediate locality; preferably before conquest, but if necessary following a suitable interval after their capitulation, these could be granted autonomy in return for submission to Roman hegemony, contributions to Roman resources and assistance in the business of government. Rome entered into countless treaties with different states, kingdoms and city-states, generally on its own terms, whether or not they were formally incorporated into a province at that stage.27 Centuries later, provinces like Sicily and Asia still displayed their origins in this piecemeal process of aggrandisement, appearing as patchworks of different sorts of allies and subjects with different statuses and privileges: free cities, cities with both freedom and exemption from taxes, allies and federates, Roman colonies, Latin colonies.28 Most of these differences, with the exception of those cities who gained valuable exemptions from certain taxes or duties, related to status rather than to anything more material; all cities, even those officially ‘free’, were ultimately subject to Rome and therefore to the local governor – if he chose to intervene in their affairs. For the most part, however, governors respected local autonomy; cities were left to manage their internal affairs – finance, buildings, festivals, law and order – just as they had done before the arrival of Rome, so long as they managed them competently and did nothing that might jeopardise Roman interests. The Romans were happy to tolerate diversity in local organisation; in Greece, for example, they permitted cities to continue to hold popular assemblies to ratify laws passed by the local senate, although this was quite different from their own oligarchic model of city governance.29

The principles of Roman rule in such regions are clearly visible in the letters exchanged between the governor of Bithynia in Asia Minor and the emperor Trajan; the governor, Pliny the Younger, clearly possessed the right to intervene in local affairs and to impose his wishes on one or all of the cities in his province, but constantly sought reassurance from the emperor as to whether or not this was appropriate in any particular case. For example, he asked for a judgement on whether he should establish a uniform practice in the province regarding the payment of a fee by someone wishing to enter the local senate, ‘for it is only fitting that a ruling which is to be permanent should come from you, whose deeds and words should live for ever’. Trajan replied:

It is impossible for me to lay down a general rule whether everyone who is elected to his local senate in every town of Bithynia should pay a fee on entrance or not. I think then that the safest course, as always, is to keep to the law of each city, though as regards fees from senators appointed by invitation, I imagine they will see that they are not left behind the rest.

Pliny, Letters, 10.112–13

In considering the relationship between Rome and the provincial cities, it is important to keep in mind that the Romans did not deal directly with the vast majority of their subjects. They sought to establish relationships with the dominant local elite, usually a status-conscious, city-based aristocracy whose power was based on birth, wealth, land ownership and the monopoly of religious and political offices – in other words, their own kind of people – and to rely on them to operate the local systems of control and domination. There were clear advantages for this elite, both individually and collectively, in cooperation with the ruling power, especially as it became clear that the loss of full autonomy was unavoidable in the face of Roman military power. They retained their position at the head of local society, and gained access to a wider range of material, social and even coercive resources with which to entrench their power. Frequently the interventions of Roman governors and emperors in the provinces were intended to bolster their supporters and reinforce their ties to Rome.

Individuals and their families were rewarded through grants of Roman citizenship, exemptions from taxes or duties, and other privileges, whether honorific titles or the right to collect certain dues from their fellow-countrymen; less formally, they might be favoured by the governor in court cases against their local rivals. Friendly cities might be granted special honours (given the status of a Roman colony, for example) or given grants to assist in public building projects, enhancing their status against neighbouring cities. Both of these processes can be charted in the epigraphic record, with inscriptions recording and advertising the achievement of civic status, the benevolence of the governor, the Roman affiliations of an individual family and so forth. In addition, the Romans might intervene to support the aristocracy as a collective, bolstering its coercive powers through the imposition of law and the occasional deployment of force to control crime or unrest; see for example Pliny’s letter enquiring whether the town of Juliopolis might be given a small garrison of Roman soldiers, as had been done for Byzantium: ‘Being such a small city it feels its burdens heavy, and finds its wrongs the harder to bear as it is unable to prevent them. Any relief you grant to Juliopolis will benefit the whole province, for it is a frontier town of Bithynia with a great deal of traffic passing through it’ (Letters, 10.77). In this case the request was turned down on the grounds that all the cities in the province would want such a garrison; the governor was simply urged to be active in preventing injustice – that is to say, in maintaining the status quo and supporting the local elite.

The great advantage for the Romans in their implementation of this policy, in contrast to the experience of modern imperial powers, was the ease with which they could accept provincial aristocrats as allies and partners rather than merely subjects, and even allow them access to higher levels of power in the Empire. From an early date, Rome’s conception of citizenship was quite different from that found in other Mediterranean city states, where the citizen body was a tightly-knit, homogeneous and exclusive group. According to one of its founding myths, the city’s original growth was based on Romulus’ creation of the Asylum, welcoming as full members of the community runaway slaves, exiles, criminals and anyone else who wished to join.30 Either in homage to this principle, or as a policy that was then justified through the myth, in the course of their expansion the Romans granted citizenship (in several different forms, with varying rights to political participation) to individuals and allied communities in Italy and beyond; following the revolt of the allies in the early first century BCE (the Social War), they extended full citizenship to the whole of sub-alpine Italy. The rest of empire’s population were not made citizens en masse until the third century CE, but over the previous centuries increasing numbers of provincials had already achieved this status, whether through individual grants or, in some cities, simply by serving as local magistrates.31

There is that which certainly deserves as much attention and admiration as all the rest together. I mean your magnificent citizenship with its grand conception, because there is nothing like it in the records of all mankind. Dividing into two groups all those in your empire – and with this word I have indicated the whole civilised world – you have everywhere appointed to your citizenship, or even to kinship with you, the better part of the world’s talent, courage and leadership… In your empire, all paths are open to all. It was not because you stood off and refused to give a share in it to any of the others that you made your citizenship an object of wonder. On the contrary, you sought its expansion as a worthy aim, and you have caused the word Roman to be the label, not of membership in a city, but of some common nationality, and this not just one among all, but one balancing all the rest… Many in every city are fellow-citizens of yours no less than of their own kinsmen, though some of them have not yet seen this city [Rome]. There is no need of garrisons to hold their citadels, but the men of greatest standing and influence in every city guard their own fatherlands for you.

Aelius Aristides, Oration 26 ‘To Rome’, 59–64

The Roman attitude was almost entirely pragmatic; rather than applying any test of racial purity or ideological compatibility to potential collaborators, they looked simply for a comparable way of life and similar attitudes to their own, and rewarded extensive services and loyalty. Modern defenders of the British Empire, embarrassed by the contrast, remarked sourly that ‘the Romans were not called upon to deal with large numbers of coloured races’ and that ‘it would be perhaps more accurate to say that all Roman citizens became lowered to the level of Roman subjects, than that all Roman subjects were raised to the level of Roman citizens’, while cheerleaders for the United States pointed to its relative generosity in extending citizenship to aliens.32 Meanwhile, the ‘ideology’ of provincial elites was simply their right to rule; there was no nationalistic, religious or ideological basis for sustained opposition to Roman hegemony, and none developed thereafter.33 Social divisions within the Empire were based primarily on wealth and status, not race or origin; able and ambitious provincials not only retained their local power but could aspire to the higher levels of the imperial hierarchy. Competition for local office became in some cases less an end in itself than a springboard for getting a family member into the Senate or the imperial service; some Greek sources made disparaging remarks about those who were not content with honour and glory in their own city but wished to be Roman senators (e.g. Plutarch, Moralia, 470C). The rewards for cooperation and conformity were an important factor, if not the most important factor, in the process of the adoption of elements of a common culture across the whole Empire, discussed in chapter 4. For the Romans, it meant that all those who might have spearheaded resistance to their rule were instead bound to them, individually and collectively, through ties of dependence and mutual advantage, and focused on competing with one another for prestige and advantage according to rules established by the Empire.

Roman rule, even in the most cooperative provinces, always combined sticks with carrots. The total number of Roman troops in the Empire was relatively small, as seen in the fact that they had to move legions between different frontiers according to immediate need, but their importance lay as much in creating the aura of power and the sense of threat as in any direct action.34 Especially under the Republic and the early emperors, Rome sometimes intervened to reshape the provincial landscape for its own purposes, establishing colonies of settlers or former soldiers on confiscated land or amalgamating small cities into larger, more easily controllable centres.35 This offered a means of punishing less favoured cities, while the threat of such action, on the whim of the ruling power, emphasised to provincials the importance of energetic collaboration:

For some reason Augustus, perhaps because he thought that Patrae was a good harbour, took the men from other towns and collected them here, uniting with them the Achaeans from Rhypes, which he destroyed. He gave freedom to the people of Patrae and to no other Achaeans; and he also granted all the other rights and privileges that the Romans customarily give to their colonists.

Pausanias, Description of Greece, 7.18.7

Much more important in the pacified areas of the Empire were the informal means of coercion; above all, intervention in the competitions within and between cities for prestige and imperial favour. Just as the governor or emperor might dispense honours, so they could withhold them, award them to a rival, choose one city rather than another to billet troops or requisition supplies, ignore or reject some petitions rather than others. The consequences of this policy of divide and rule can be seen in the flurry of letters and embassies from different cities on the accession of every new emperor, reporting on the erection of statues and the voting of new honours to him, seeking to have rights and privileges confirmed and to curry favour with the new regime, trying to strike the right level of obsequiousness. On the accession of Claudius in 41 CE, the city of Alexandria had particular need to grovel, following serious rioting between its Greek and Jewish populations, and Claudius’ official reply shows the combination of condescension and veiled threat with which subject cities were kept in line:

Wherefore I gladly accepted the honours given to me by you, though I am not partial to such things. And first I permit you to keep my birthday as an Augustan day in the manner you yourselves proposed, and I agree to the erection by you in their several places of the statues of myself and my family; for I see that you were zealous to establish on every side memorials of your reverence for my household… As for the erection of the statues in four-horse chariots which you wish to set up to me at the entrance to the country, I consent to let one be placed at the town called Taposiris in Libya, another at Pharus in Alexandria, and a third at Pelusium in Egypt. But I deprecate the appointment of a high priest for me and the building of temples, for I do not wish to be offensive to my contemporaries, and my opinion is that temples and the like have by all ages been granted as special honours to the gods alone.

Concerning the requests which you have been eager to obtain from me, I decide as follows… It is my will that all the other privileges shall be confirmed which were granted to you by the emperors before me, and by the kings and by the prefects, as the deified Augustus also confirmed them… As for which party was responsible for the riot and feud…I was unwilling to make a strict enquiry, though guarding within me a store of immutable indignation against any who renewed the conflict; and I tell you once and for all that, unless you put a stop to this ruinous and obstinate enmity against each other, I shall be driven to show what a benevolent emperor can be when turned to righteous indignation.36

The Roman template for control was most effective in regions like Sicily, Greece and Asia Minor which had long been dominated by more or less autonomous city states and a clearly differentiated aristocracy, who could be recruited as collaborators. Elsewhere, the model had to be implemented more gradually. In Egypt, which had no tradition of self-governing cities, the Romans simply took over the system of bureaucracy established by the previous regime, recognising it as efficient and convenient for their purposes; urban centres were not granted any degree of independence or responsibility until the early third century CE.37 Other regions, above all in the west, offered neither city-states nor any alternative form of administrative infrastructure; as they had previously done in parts of Italy, the Romans therefore sought to encourage changes in native society in order to make it more amenable to their rule.38 Even before conquest, their influence was significant; studies of the peripheries of more modern empires has shown how tribalisation, generally assumed to be the traditional form of social organisation, is in fact a response to the proximity of an imperial power, as a previously diverse society with little in the way of social hierarchy gives power to leaders for the purposes of negotiation and war.39 Having annexed the territory, the Romans looked to these tribal leaders to control the rest of the populace – effectively, through gifts of land, titles and other support, turning them into the kind of hereditary aristocrats, competing with one another for honour and status, with which they were familiar elsewhere. Cooperation provided these new elites with the prestige goods and other resources they needed to entrench their power – as indeed they had already been doing before the conquest, as revealed by the presence of unmistakably Roman items amongst the grave goods of some burials.40

This process was closely related to the progress of urbanisation; to judge from the archaeological evidence, the emergence and development of cities was a mixture of deliberate creation, Roman encouragement and spontaneous development. In Britain and northern Gaul, for example, roughly half of known civitas sites were founded on or near earlier native settlements, with others on the sites of military camps.41 The establishment of an urban culture in the western provinces is often regarded as one of prime benefits of Roman imperialism for its subjects, and thus as a straightforward marker for the progress of civilisation in less developed regions. Certainly Greek and Roman sources held the view that civilisation was intimately connected to urbanism – note for example Strabo’s comments about the Gauls in the region of Massilia who ‘became more and more pacified as time went by, and instead of engaging in war have turned themselves to civic life and farming’ (Geography, 4.1.5).42 One of the motives for the efforts of Roman governors to promote city-building and to provide models for city organisation, like the charters known from Spain, may indeed have been the wish to lead provincial nobles towards proper conformity with Roman values by encouraging them to adopt the correct constitutional and social structures, in the expectation that this would influence their behaviour.43 But the tendency in Western culture to associate cities with modernity and progress, and hence to regard urbanisation as a good thing in itself, should not lead us to ignore its role in establishing new orders of power in provincial society, and thus entrenching Roman rule.44 Tacitus offered a far more cynical view of the process in England:

In order that a population scattered and uncivilised, and proportionately ready for war, might be habituated by comfort to peace and quiet, he would exhort individuals and assist communities to erect temples, market places and houses; he praised the energetic, rebuked the indolent, and the rivalry for his complements took the place of coercion.

Agricola, 21.1

Discussions of urbanisation, in both ancient and more modern history, have tended to focus on attempts at defining ‘the city’, whether according to ancient conceptions of the city as a political, religious and social centre or modern ideas of the city as market and industrial centre.45 This can lead to fruitless arguments about whether a particular centre meets the threshold criteria to be counted as a ‘proper’ city, as well as reinforcing the Western myth that cities are agents of modernisation, acting dynamically on any society in which they are planted.46 Rather, urbanisation is best understood as an ongoing process, one of the products of the confluence of four different processes of social, economic and cultural change: concentration, crystallisation, integration and differentiation.47 Each of these processes of change is closely related to social power – which is precisely why both the Roman state and various native elites chose to invest a significant proportion of social surplus in their development. The concentration of both people and resources in nucleated settlements rather than scattered across the countryside made them easier for the local elite to control; the emergence of an urban hierarchy, as certain sites developed further because of their position within networks of exchange and information and smaller sites became increasingly dependent on them, gave power to those further up the hierarchy, above all to the city of Rome at its apex.48 The ‘crystallisation’ of institutions (a better term than ‘centralisation’, since it is not necessarily a deliberate process), so that political, social, religious, cultural and economic institutions came to be co-located in the city, led to the overlapping and mutual reinforcement of different sources of power, all for the most part controlled by the same urban elite. Different forms of integration – drawing ever larger numbers of people into the same political institutions, eroding differences of language, customs and material culture, fostering the development of a social identity beyond that of kinship, drawing ever larger numbers of people into exchange networks and the market – created homogeneity out of diversity, and thus made the society more susceptible to rule. Economic differentiation made the concentration of people in cities possible, increased their interdependence and reinforced the power of those who controlled the bulk of the land and other resources; political and social differentiation reinforced the distinction between the elite and the rest of the population, and marked the former out as suited by nature and upbringing to rule the latter.49 In summary, while the development of cities in the western provinces may indeed have had some beneficial economic and cultural consequences for the mass of the population, the Romans’ primary motive in promoting urbanisation was self-interest: by encouraging their western subjects to become more like those in the central and eastern Mediterranean, they reinforced the power of the local elite over their people in order to make their own dominance as secure and cost-effective as possible.

Whether in the east or west, Roman rule had a significant impact on provincial society. Even where the Romans simply adopted and maintained local systems of dominance, they altered the conditions under which the local elite competed for power, and reinforced their control of the masses through access to power and resources, as well as new forms of coercion and ideology like the cults of Rome and of the emperors. At the same time, they risked undermining the relationship between elite and mass, whether through their demands for taxes or requisitions (which the elite had to extract from their people) or through the centripetal forces of Roman culture and power, so that an outward-focusing elite, adopting the trappings of ‘Romanness’, might become ever more alienated from the rest of the population. In other parts of the Empire, they sought to introduce a whole new structure of society and new forms of social and political behaviour, conforming to their own expectations, with a dramatic increase in the power of the elite over the rest; in order for their potential collaborators to be useful, they had to be given the power to coerce and exploit their people on the Romans’ behalf.

Inevitably this provoked resistance, especially when the changes were rapid and far-reaching, as is suggested by the accounts of revolts in Germania and Gaul. The crucial question is how long such resistance may have lasted, once it ceased to take a violent – and hence historically visible – form, especially as the literary sources and inscriptions from the provinces were generated by those who had thrown their lot in with Rome. As noted above, while Rome always held the threat of military action in reserve, there is little trace of political or military opposition in the pacified regions; historians have sought instead to identify resistance to ‘Romanisation’ in the patterns of consumption amongst the wider population that are revealed by the material evidence. For example, the decline of the urban centres known as the civitas capitals in Britain from the second century CE has been interpreted as resistance to the rule of the pro-Roman tribal elite.50 The great advantage for the Empire in its chosen style of domination was indeed that, for the most part, any hostility would be directed against the local elite who had to implement their demands and collect their taxes or who took advantage of their privileged position to oppress and exploit the population. Once the initial disruption of conquest was past, the Romans ceased to be the clear enemy; it seems entirely possible that their domination was effectively invisible to the majority of the population, a matter of regular concern only to the client ruling class.

In general, serious problems arose only when the Romans encountered unfamiliar forms of society; as they did elsewhere, they fixed upon the group that looked most like their kind of aristocrats, to the exclusion of any other influential groups, and sought to promote them as proxy rulers regardless of their actual level of popular support. In first-century CE Judaea, the most important example of this, they favoured the Jewish landowning aristocracy and largely ignored those who held religious authority – the idea that these two sources of power could be entirely separate was alien to Greco-Roman culture. The aristocracy struggled to impose its authority on the populace, and was thus increasingly ignored by the governor; seeking an alternative source of power, Jewish nobles courted popularity by leading resistance against Rome instead.51 The Jewish revolt had a number of different causes, above all the conduct of Roman officials and a lack of respect for religious sensibilities (not least Caligula’s wish to have a statue of himself installed in the Temple), but the crucial difference from other provinces was that the Romans sought to rule through people who should never have been entrusted with power. In Gaul and Britain, meanwhile, the Romans first ignored the Druids, favouring a more traditional warrior aristocracy as their collaborators, and then sought to exterminate them as a source of power and influence separate from the aristocracy and not integrated into Roman rule. They were more successful here than in Judea, but the question remains whether pacification might have been more or less straightforward if they had been willing to show flexibility in their approach to provincial rule.

Roman Provincial Government

Roman administrative structures were minimal, keeping the costs of empire low, because most tasks were outsourced to local collaborators, and because the aims of Roman rule were equally minimal: to maintain order or at least prevent outright conflict, to maintain the flow of taxes and recruits, and to ensure continuing submission. The Romans felt little sense of any obligation to their subjects. Taxes and tribute were collected as the reward for their dominance and as recompense for the expenses of conquest. At best, they offered the logic of protectionism, levying taxes in return for the absence of war, as Cicero wrote to his brother:

The province of Asia must be mindful of the fact that if it were not a part of our empire it would have suffered every sort of misfortune that foreign wars and domestic unrest can bring. And since it is quite impossible to maintain the empire without taxation, let Asia not grudge its part of the revenues in return for permanent peace and tranquillity.

Letters to his Brother Quintus, 1.1.34

The belief of later historians, especially in nineteenth-century Britain, that Roman imperialism was driven by a mission to bring civilisation to the unenlightened barbarians was entirely misplaced. The Romans certainly noted the impact of their rule on provinces in the west, but in so far as they encouraged aspects of this development it was entirely for their own ends, and left largely in the hands of the provincials. Even in the city of Rome, which benefited from the spoils of empire in the form of public buildings and a reliable grain supply, the ancient state took upon itself few of the activities or responsibilities associated with modern states – education, housing, economic management, poor relief, health – and thus it had no need for any elaborate infrastructure. In the provinces, the minimal obligations of the ruling power to the masses (provision of public sacrifices and festivals, action in case of major food crisis) were left almost entirely to local notables.52

Indeed, by modern standards Roman provincial government was almost entirely unsystematic and amateurish. Roman governors received no formal training in administration or financial affairs, having been appointed as the result of political machinations in the senate or of the emperor’s favour, and their staff was made up of dependents and friends rather than professional administrators.53 That this was possible, with remarkably few adverse consequences in the course of the Empire’s history, was due to the nature of their task: not administration but negotiation and politicking, balancing the competing demands and interests of different cities, different factions within those cities and other groups in provincial society, including tax farmers and Roman and Italian ex-pats, whether settlers or merchants. Cicero’s summary of his achievements in Cilicia gives a clear indication of the expectations of the governor’s task: ‘I have rescued the communities and have more than satisfied the tax-farmers. I have offended nobody by insulting behaviour. I have offended a very few by just, stern decisions, but never so much that they have the audacity to complain’ (Letters to Atticus, 6.3.3). The essential skills for the job were those of a skilled politician, not an efficient administrator, and the Roman political system was an ideal source of such men.

The governor had broad freedom of action within his own province, and was not even bound by precedents set by his predecessor. This was a Roman tradition, deriving from the old idea of the magistrate’s imperium, the expectation of obedience, but it was also a necessity to enable him to respond effectively to unpredictable situations, especially given the length of time it might take to inform Rome of a problem and receive further instructions. The same can be said of his role as the highest judge and arbitrator within the province, aiming to balance the interests of justice (as he saw it) with more pragmatic considerations about the identities of those involved and the likely reaction of different groups to a particular decision. Much of this power was held in reserve; most governors, especially under the Principate, preferred to avoid action despite the entreaties of different cities or petitioners, precisely because it might upset the balance between competing elements, and their role in the law was tempered by the expectations of the provincials and the complex relationship – the creative tension, as it has been suggested – between Roman and indigenous law and custom.54 The governor’s power was limited too by the size of the province relative to his resources; his inability to be everywhere at once, and hence his reliance on local aristocrats for information – which must almost invariably have been distorted or censored in their own interests. Furthermore, he was always caught between local and central demands, and – at least to judge from the correspondence between Pliny and Trajan – chronically short of resources:

Pliny to Trajan: Will you consider, sir, whether you think it necessary to send out a land surveyor? Substantial sums of money could, I believe, be recovered from contractors of public works if we had dependable surveys made…

Letters, 10.17, 10.18

Trajan to Pliny: As for land surveyors, I have scarcely enough for the public works in progress in Rome or in the neighbourhood, but there are reliable surveyors to be found in every province, and no doubt you will not lack assistance if you take the trouble to look for it.

Under the Principate the governor faced both ways, representing the emperor to the provincials but also representing his province to the centre, aware of how its behaviour might reflect on his own stewardship and hence affect his standing with the emperor:

Pliny to Trajan: We have celebrated with appropriate rejoicing, sir, the day of your accession, whereby you preserved the Empire; and have offered prayers to the gods to keep you in health and prosperity on behalf of the human race, whose security and happiness depends on your safety. We have also administered the oath of allegiance to the troops in the usual form, and found the provincials eager to take it too as a proof of their loyalty.

Letters, 10.52, 10.53

Trajan to Pliny: I was glad to hear from your letter, my dear Pliny, of the rejoicing and devotion with which under your guidance the troops and provincials celebrated the anniversary of my accession.

The Roman approach to provincial government was flexible, easily accommodated to local circumstances and, above all, cheap, but there were some obvious flaws in the system – not only for provincials, but even for Rome. Firstly, the process of appointment of governors did not necessarily yield the most skilled politicians for each province; some assignments were fought over fiercely, and won by those candidates best able to marshal support and call in favours, but less popular and lucrative regions were given to anyone who couldn’t evade the fact that it was their turn (Cicero, for example, was deeply reluctant to shoulder the burden of governing Cilicia, despite his self-presentation as one of most noble and self-sacrificing of Roman notables). Under the Principate, meanwhile, imperial provinces might be assigned according to the whims of the emperor’s patronage, and success in toadying to a single absolute ruler to win an appointment was not necessarily replicated in dealing with the competing demands of provincials. Secondly, governors’ terms of office were generally short, barely a year under the republic: there was thus no continuity in the administration (since the governor’s staff were attached to him rather than the province), little opportunity to develop administrative ability or knowledge of the province and its people, and no need to shoulder the burden of mistakes – Cicero openly expressed his wish to avoid a prolongation of his duties in Cilicia, on the grounds that he had gained as much glory as was available and risked losing it as a result of unexpected events. The situation improved gradually under the Principate, with longer terms of office becoming the norm, but now a governor could be recalled at a moment’s notice as a result of imperial whim or any change in the balance of influence in the imperial court.

Most notoriously, the wide powers of the governor and the nature of his task created enormous opportunities for abuse in the cause of personal, rather than state, enrichment. This is implicit even in accounts of exemplary governors, like Cicero’s self-presentation or Tacitus’ account of his father-in-law Agricola:

He decided therefore to eliminate the causes of war. He began with himself and his own people: he put in order his own house, a task not less difficult for most governors than the government of a province. He transacted no public business through freedmen or slaves; he admitted no officer or private to his staff from personal liking, or private recommendation, or entreaty; he gave his confidence only to the best. He made it his business to know everything; if not always to follow up his knowledge; he turned an indulgent ear to small offences, yet was strict to offences that were serious; he was satisfied generally with penitence rather than punishment; to all offices and positions he preferred to advance the men not likely to offend rather than to condemn them after offences.

Agricola, 19.1–4

This encomium reveals some of the typical deficiencies of other governors, even those who were basically honest and well-intentioned; it is misleading only insofar as it implies that the problems were entirely due to a lack of moral fibre or common sense, rather than to the nature of the system. Above all, the governor might well be ignorant (wilfully or not) of what was being done in his name, as his subordinates took advantage of the power gained from their proximity to power, their access to the governor and their ability to filter the information he received. As was also the case at the heart of the Empire, the volume of business was greater than any individual could manage; those who managed the governor’s paperwork had significant influence on which cases were given priority. The evidence suggests that most corruption in the legal system was not aimed at affecting the outcome of cases but at moving them up the queue for consideration.55

The governor’s subordinates were generally appointed through personal or family connection. In theory, that placed them under personal obligation to him, but it might equally tie his hands in dealing with their misdemeanours; a nephew, or the son of a powerful ally, cannot be dealt with in the same way as an incompetent or corrupt bureaucrat. Roman society was organised around complex networks of friendship, influence and patronage, operating through favours, obligations and unwritten expectations of reciprocity and gratitude: according to the philosopher Seneca, the exchange of services and favours – beneficia – was the basis of social cohesion.56 This affected not only the governor’s relations with his staff but also much of his day-to-day activity. To judge from their correspondence, both Cicero and Pliny spent much of their time as governors dealing with letters, requests and introductions from friends and other connections, all of which implied or assumed that they should make use of their power on the writer’s behalf. Cicero, for example, received a letter in Cilicia from a friend, demanding that he should arrange for large numbers of panthers to be sent to Rome for the games, and then continuing:

I recommend to you M. Feridius, a Roman eques, the son of a friend of mine, a worthy and hard-working young man, who has come to Cilicia on business. I ask you to treat him as one of your friends. He wants you to grant him the favour of freeing from tax certain lands which pay rent to the cities – a thing which you may easily and honourably do and which will put some grateful and sound men under an obligation to you.

Letters to his Friends, 8.9.4

It was hardly in the interests of the Cilician cities to lose a portion of their revenue; Cicero declined to grant this request, but plenty of other governors might have done so, as a means of reinforcing a friendship, building up obligations and maintaining their client base. Under the republic, it is clear that governors faced a particular issue in managing their relations with the publicani, the contractors who had bought up contracts for provincial tax collection and who inevitably sought to make largest possible profit on their investment, at the expense of the provincials. Cicero was explicit about the dilemma:

If we oppose them, we shall alienate from ourselves and from the state an order that has deserved extremely well of us… and yet if we yield to them in everything, we shall be acquiescing in the utter ruin of those whose security, and indeed whose interests, we are bound to protect.

Letters to his Brother Quintus, 1.1.32

Apparently you want to know how I handle the tax-contractors. I cosset them, I defer to them, I praise them eloquently and treat them with respect – and I see to it that they don’t bother anyone… So the Greeks pay at a fair rate of interest and the publicani are very pleased because they have full measure of fair words and frequent invitations from me. So they are all my intimate friends and each one thinks himself especially favoured.

Letters to Atticus, 6.1.16

Furthermore, the governor had to judge his relationships with different provincials, deciding which ones to trust and favour in order to keep the province manageable. In his long list of advice to his brother on provincial government, Cicero advised caution in dealing with those who profess deep friendship and affection for the governor, ‘especially when those same persons show affection for hardly anyone who is not in office, but are always at one in their affection for magistrates’ (Letters to Quintus, 1.1.15).

In your province there are a great many who are deceitful and unstable, and trained by a long course of servitude to show an excess of sycophancy. What I say is that they should all of them be treated as gentlemen, but that only the best of them should be attached to you by ties of hospitality and friendship; unrestricted intimacies with them are not so much to be trusted, for they dare not oppose our wishes, and they are jealous not only of our countrymen but even of their own.

Letters to Quintus, 1.1.16

It is easy to imagine the temptation for the governor, obliged by his duties to establish relationships with both the leading families of his province and the publicani, to show favouritism to his friends, fall into compromising situations or find himself under obligation to particular individuals or cities. It is equally easy to imagine the opportunities for personal enrichment that a less scrupulous governor could find in his position, above all in the need for provincials to seek his favour and avoid his displeasure. Cicero’s famous prosecution of Gaius Verres for misconduct in his term as governor of Sicily offers numerous examples, and makes it clear that most of the time there was no need for the governor even to threaten legal action, let alone to abuse his powers, in order to exact compliance – a simple request, with the authority of the governor behind it, was generally sufficient. Verres is said to have tried to seduce the daughter of a provincial notable by billeting one of his underlings in the household (Against Verres, II.1.65–9); to have seized works of art from private individuals by asking to borrow them so that he could inspect them, or simply ordered communities to hand over statues on public display (II.2.88); and to have fraudulently claimed the estates of wealthy men after their death (II.2.35–49). He accepted bribes to alter a verdict (and then condemned the man anyway, in Cicero’s view an even worse crime than simple corruption; II.2.78), bribes to allocate a seat in the local senate and a post as a priest (II.2.123–4, 127), bribes to alter the tax assessment of rich individuals and to exempt particular cities from supplying sailors or ships – but he did then have a merchant ship built for himself at the expense of the city, to carry off his ill-gotten gains (II.2.138, II.4.21, II.5.20, II.5.61). An entire section of one of Cicero’s speeches (II.3.162–228) dealt with Verres’ abuses in the collection of corn for Rome: money sent from Rome to buy corn was embezzled; Sicilian farmers were forced to hand over whatever level of tax the collectors demanded (they could go to law to apply for a reassessment afterwards, but that was scarcely a realistic possibility for most); rather than requisitioning corn for the upkeep of his own household as was expected, Verres demanded money instead and levied this at a rate far in excess of the market price for corn. The cities were intimidated into silence; the publicani, who had benefited from their share in the excessive exactions, passed a resolution to expunge any of their records that might be damaging to Verres’ reputation.

It is worth noting that Verres did make some attempt to cover his tracks; this level of abuse went beyond the limits of acceptability even in Rome, not least because some of his actions were directly contrary to Roman interests, and there was at least a theoretical possibility that a corrupt or abusive governor could be held responsible for his actions. Under the republic, he was immune from prosecution during his term of office; in theory, an appeal could be sent to the senate, which might set up an enquiry or send out an embassy, but in practice they would respond only to most powerful, above all the groups of publicani, not to mere provincials. After his term of office a governor could be prosecuted, as Verres was, back in Rome, but it is clear from the speeches that a successful prosecution was very rare. Cicero listed the range of expedients, including the appointment of a tame prosecutor and attempts at delaying the trial for as long as possible by starting a rival prosection, which were available to someone who had amassed sufficient funds and allies during his time in office. The corrupt governor’s greatest protection, however, was the tendency of senators to support their own, and to regard a certain level of extortion, provided that it was not too obvious, as part of the privileges of office. Cicero noted the widespread perception ‘that these courts, constituted as they now are, will never convict any man, however guilty, if only he has money’ (I.1).

A conviction – or, in the case of Verres, a fear of conviction leading him to flee into exile – depended less on the strength of the prosecution’s case or the level of abuse than on external circumstances. The main hope for provincials was if the accused had powerful political enemies who would seize upon an excuse to attack him; Cicero’s case, meanwhile, succeeded because the senate was threatened with losing control of the extortion court and so needed to be seen to put its own house in order. Under the Principate, provincials had the right of appeal to the emperor, but that was unlikely to be effective against one of his favourites and could have repercussions; their condition was effectively subject to the emperor’s whims and to court politics. In either period, they might be better advised to keep quiet and accept a certain level of extortion – or, since the provincial cities themselves were rarely united, to seek to win the governor’s favour and so direct his greed towards their rivals. Cicero’s remark on this subject was intended to shame his fellow senators into, for once, convicting one of their own, but it reflects a basic truth about the nature of Roman provincial government:

I said I believed the day would come when our foreign subjects would be sending deputations to our people, asking for the repeal of the extortion court. Were there no such court, they imagine that any one governor would merely carry off what was enough for himself and his family; whereas with the courts as they now are, each governor carries off what will be enough to satisfy himself, his advocates and supporters, and his judges and their president; and this is a wholly unlimited amount. They feel that they may meet the demands of a greedy man’s cupidity, but cannot meet those of a guilty man’s acquittal.

I.41

The Empire’s Longevity

Corruption is not necessarily a problem for a society if it is moderate and predictable; as noted above, Roman society constantly trod the fine line between gifts and bribery, friendship and favouritism, reciprocity and corruption. The need for flexibility and judgement, rather than strict regulation, was even enshrined in law:

A proconsul need not entirely refrain from ‘guest-gifts’ (xenia), but only set some limit, not to refrain entirely in surly fashion nor to exceed the limit in grasping fashion… For it is too uncivil to accept from nobody, but contemptible to take from every quarter, and grasping to accept everything.

Digest, 1.16.6.3

Extortion and corruption became a serious problem for provincial government only when they upset the balance between different groups, creating disorder and disrupting tax collection; in other words, when the private interests of the governor came into direct conflict with the interests of Rome. Under the Principate, the nature of oversight shifted from the regulation of friends and colleagues by former and aspiring governors in the senate to the regulation of his subordinates by the emperor. There was an increase in the number of officials with specific financial responsibilities, above all for managing the vast imperial properties and for collecting taxes; these were equestrians and occasionally freedmen, not senators, and so directly dependent on the emperor and (in theory) less likely to pursue their own interests to any great extent.57 Part of the motivation for these changes may have been to improve the quality of government and to protect the provincials from exploitation – the emperors did, after all, present themselves as the protectors of the whole Empire, and draw legitimacy from this – but at least as important was the need to maximise imperial revenue and to prevent any governor or general from gaining too much power and so becoming a threat. Nevertheless, the problems of distance and the slowness of communication meant that the emperor was always reliant on the reports of his own officials, only occasionally supplemented by other reports or petitions from the province. The Empire was too large, the technology too limited and the administrative structure far too sparse to permit intensive regulation or control.

Rather, Roman rule worked on the basis of a confluence of interests: it was in the interests of local elites to cooperate and to keep their populations quiet, it was in the interests of governors to keep their provinces well-behaved and so to moderate their rapaciousness, and it was in the interests of the Empire as a whole to limit its interference in local affairs. Each party gained a share of whatever surplus could be extracted from the mass of the population. The local rulers perhaps had to settle for a smaller share than they had enjoyed during periods of full independence, but instead they gained access to Roman power and resources and the opportunity to aspire to higher office as part of the imperial system. The Empire and its rulers had to settle for a smaller share than they might have been able to extract, but were spared the costs of administration that would have been involved in establishing direct control rather than working through intermediaries.