Medieval society is popularly believed to have been obsessed with death.

By Dr. Sophie Oosterwijk

Art Historian, Freelance Lecturer, and Editor

Introduction

Medieval society is popularly believed to have been obsessed with death: the motto memento mori (remember that you must die) is used to characterise the period, whereas the Renaissance is summed up by Horace’s aphorism carpe diem (seize the day). The two labels are essentially two sides of the same coin, but the first suggests a morbid state of mind with an unhealthy focus on mor-tality whereas the second seems much more positive and indicative of a change in mentality. The Dutch historian Johan Huizinga devoted a whole chapter of his 1919 study Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen (translated originally as The Waning of the Middle Ages) to the constant reminders of one’s own mortality that we find in art, literature and drama of the fifteenth century, citing the Danse Macabre as a prime example of how the transience of earthly beauty was visu-alised in this period.1

Memento mori is indeed the primary message of the Danse Macabre, a medieval textual and/or visual motif that acquired a widespread popularity across Europe in the fifteenth century.2 However, the Danse conveyed yet another message: it also served to demonstrate to contemporary viewers how Death wreaks chaos and disorder by disrespecting the social hierarchy of this world and by despatching its victims indiscriminately, regardless of age, wealth, or status. Everyone is equal before Death – even mighty kings – and the naked dancing corpses underline how every vestige of one’s social identity is erased in death. In a world in which every citizen knew their divinely ordained place in Christian society, this brutal truth must have been disturbing rather than comforting as it calls into question the value of rank and social order. Yet the Danse did not just address the individual on a social and moral level. As this chapter will also show, it was probably two royal deaths in quick succession, and the national trauma and social disorder they left in their wake on both sides of the Channel, that led to the creation of two famous Danse Macabre mural cycles in Paris and London. These in turn inspired the spread across Europe of a motif that has continued to appeal to this very day, precisely because it func-tions at both a moral and a social level and because it still has the power to shock and unsettle the viewer.3

This chapter aims to contextualise the Danse and analyse its multiple messages through a close reading of two of the earliest texts: the French poem that was incorporated in a famous mural in the cemetery of Les Saints Innocents in Paris in 1424–1425 and the Middle English adaptation by the monk-poet John Lydgate (c. 1371–1449), which in turn formed the basis of another famous cycle of paintings at Old St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Unfortunately both schemes were lost centuries ago, but the woodcut edition that was first published by Guy Marchant in 1485 provides us with at least an impression of the Paris mural half a century earlier, even if its illustrations evidently do not form a reli-able copy as is so often thought.4 For comparison and to illustrate the continuing fascination with the Danse, reference will also be made to the famous series of woodcuts designed by Hans Holbein the Younger designed around 1524, but published only in 1538 under the title Les simulachres & historiees faces de la mort.5

The Theme of Death in Medieval Culture

It was hard to avoid being reminded of one’s own mortality in the Middle Ages. The dead were buried within the community, either in the churchyard or inside the church.6 Those who could afford it commissioned tombstones or monuments with inscriptions by which they might be remembered with prayers for their salvation. The grave rarely offered an eternal resting place for the dead, however. Over the years most graves were re-opened to make room for the newly deceased and in many places the remains of those who had died before were transferred to charnel houses. Although this treatment of the dead was commonly in use across Europe, it could nonetheless be unsettling, as is memorably expressed by Hamlet when he is confronted with the skull of the former court jester Yorick in the graveyard scene.7 Nor were the dead themselves always believed to be at peace: fear of the restless dead or reve-nants was widespread and may have contributed to the concept of the Danse Macabre.8

The Danse Macabre was but one of many contemptus mundi motifs in medieval culture, as well as a relatively late one – too late to owe its origins to the devastating impact of the Plague that first arrived in Europe in 1347, although recurrent outbreaks thereafter are likely to have fostered a fear of death.9 Even if the use of dance as a metaphor was novel, earlier authors, playwrights and artists had already chosen the inevitability of death and the resulting corruption of the body as themes in their work. Among the many extant literary examples are the surviving fragment of an early English poem now known as The Grave, which occurs in a twelfth-century manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 343), and the slightly later lyric When the turuf is thi tuur (Cambridge, Trinity College MS 323), both of which warn the reader about the grim fate of the body after death as it lies rotting in its grave.10

There was a purpose to this horror, for graphic descriptions of bodily corruption in poems such as these and in exempla of the period served to remind audiences of the need to be mentally prepared for death and to disdain earthly pleasures in order to ensure one’s salvation. Theologians and moralists taught that by indulging in vain pleasures one risked imperilling one’s immortal soul in case one died suddenly in a state of sin without last rites and absolution. After all, dying in a state of mortal sin without an opportunity of receiving the last rites and absolution would spell eternal damnation. Even prior to the arrival of the Plague, death would strike swiftly and unexpectedly in a variety of ways: nobody was safe.

A major theme that first emerged in French poetry in the late thirteenth century was the Legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead, in which three young noblemen out hunting encounter three decaying corpses who warn them that they, too, must face death and recognise that their bodies are doomed to putrefaction.11 A belief in revenants may well have been a factor in the emergence and popularity of this exemplum, but here the dead represent but one social class, viz. the elite. In early examples of the Legend, the Dead merely admonish the Living, who are thus being given a reprieve and the chance to mend their frivolous ways. The Legend rapidly spread from poetry to art and often came to be depicted in murals and manuscripts throughout medieval Europe as a didactic lesson without any accompanying text. It was only in the fifteenth century that the Dead were shown actively pursuing the Living and threatening them with spears and scythes – an artistic develop-ment that may be indicative of an increased horror of death in the later Middle Ages or of a need to shock even the more hardened viewers. With its dialogue and visual pairing of dead and living the Legend is often seen as a precursor of the Danse Macabre, but it draws on stereotypical aristocratic behaviour and youth to paint its moral message.

Another development in “macabre” art with a memento mori message was the cadaver or transi tomb.12 First erected in the late fourteenth century, this type of monument presented the deceased not in an idealised form awaiting the second coming of Christ, but as a corpse in a state of putrefaction, near-skeletal or being devoured by worms and other vermin. Sometimes the two states of the body – the idealised representation above the putrid corpse – were juxtaposed in so-called double-decker tombs. Like medieval didactic texts on the theme of the corpse in the grave, these cadaver monuments reminded viewers of the universality and inevitability of death, while at the same illus-trating one’s faith in the bodily resurrection as expressed in Job 19:25–26.13

The cadaver tomb thus looks forward beyond the actual moment of death to both bodily corruption and the Last Judgement so that, despite its gruesome form and gory details, its message is meant to be a positive one: the corrupt state of the body is but a temporary one until God restores it to its former glory. Yet it is hard to remember such consoling thoughts when faced with the stark image of bodily decomposition: stripped of all social trappings, beauty and identity, these cadaver effigies strike the viewer with horror. Ironically it was only the wealthy and powerful who had the means to commission such monu-ments on which they are nonetheless presented as sharing the common fate of mankind.

Like the Legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead, the Danse Macabre is basically a dialogue between the living and either the dead or Death personi-fied. However, the Danse includes victims from all ranks of life and thus was meant to have a far wider appeal: it was the intention that everyone should recognise themselves in the living who are about to die. The oldest surviving poem is the Spanish Dança general de la muerte, which is usually dated around 1390–1400, yet this does not appear to have had a wide impact originally and there was no visual dissemination of the Dança in Spain at this time. Its con-nection to the French tradition is also still a matter for debate; the Spanish Dança and the French Danse may both have originated in a lost Latin prototype, in which case the translation of the theme into the vernacular and then into art would have ensured that it reached a much wider audience in need of its message about the imminence and ubiquity of death.14

In contrast to the message conveyed by cadaver tombs, the Danse Macabre rarely looks beyond the actual moment of dying nor does it offer its living protagonist a chance to repent as is the case in the Legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead. The main focus of the Danse is on the first of the Four Last Things – Death, Judgement, Hell and Heaven – and on the fact that everyone must die, not just the old and the poor but also the young, the rich and the powerful, thereby making its message widely relevant but also shocking: nobody in society is exempt. The hereafter is only alluded to indirectly. The living characters in the Danse are firmly set in the here and now, but are inclined to look back with regret to the life and luxuries that they must leave behind, thereby providing an indication of their spiritual and mental state as well as their social rank. Their Judgement is implied in their own words and those of their dead opponent in the Danse, who frequently mocks them for their pride and moral blindness. Moreover, although the living characters form a continuous chain with the dead dancers, each victim is presented in isolation: there is no appeal to other characters and no interaction with anyone but each figure’s dead opponent. Dying is thus shown to be a very lonely and even isolating experience.

The living appear to represent social order through the hierarchical manner in which they are portrayed, especially in the French poem with its tightly ordered structure. This hierarchy is still evident in Lydgate’s translation that largely follows the French original, albeit with a number of added stanzas and new characters. These and other Danse texts leave the reader in no doubt about the disorderly manner in which the ill-prepared living must leave this world – a world in which they are but pilgrims whose aim it should have been to better themselves in order to attain Heaven. As Lydgate himself put it, “this worlde is but a pilgrimage/ȝeuen vn-to vs owre lyues to correcte” (lines 37–38).15 The metaphor of a pilgrimage is telling: as Chaucer showed in his Canterbury Tales, pilgrims can represent a cross section of society, men as well as women and clerics alongside cooks and merchants, all travelling together towards a com-mon destination. Yet while the living share death as there common goal, there is no awareness that they share this final journey with their neighbours, preoccupied as they are with their own individual fate when it is already too late. In this respect, we are reminded less of Chaucer’s merry pilgrims and more of the haunting image of St James the Greater as a lonely pilgrim travelling through a wicked world on the left outer wing of the Last Judgement Triptych by Hieronymus Bosch (d. 1516) in the Akademie in Vienna.16

Whereas the characteristics of each social type summoned to join the Danse are carefully described, their actual cause of death is rarely specified: decadent living and a love of food may have been a contributing factor in the fat abbot’s demise, but there is no pauper said to be dying of starvation in either the French or the English poem. By contrast, in Holbein’s woodcut series the martial knight dies violently as Death transfixes him with a jousting lance, while the king is being offered a lethal drink by Death posing as a cupbearer.

No such cause of death is indicated in the earlier texts; only in the Danse Macabre des Femmes by the French poet Martial d’Auvergne (c. 1420–1508) does the wetnurse mention an “epidimie” – presumably the Plague – that is killing herself and the baby in her care.17 The violence that is often alluded to in the Danse, such as when the curé or parson in the French poem observes that “Il nest homme que mort nassaille” (line 418, “There is no man whom Death does not attack”), does not point to the cause of death but to the suddenness and force with which it usually hits people. This very suddenness was a major cause of fear to Christians, as stated earlier. Nor is the physical process of dying ever elaborated upon in the Danse: the texts merely speak of “assault” or “joining the dance”, whereas the imagery shows Death grabbing his victims by the hand, the arm, the shoulder, or their garment.

There is thus the shock of the encounter but no description of physical pain, unless one includes other related imagery of Death hitting his victim with an arrow or spear. Instead, the horror of the fate of the body after death is illus-trated by the physical appearance of the dead dancers, who are sometimes regarded as the alter ego of the living. This begs the question whether the dead in the Danse represent Death personified or the dead who have risen from their graves to seize the living; a vexed question that often hinges on the interpretation of the term le mort in the French poem.18 Whatever the nature of Death or le mort, the living and the dead dancers clearly represent two sepa-rate states, albeit that the former must become like the latter. This transition entails the loss of earthly beauty, physical strength, status and individuality, for one corpse looks pretty much like the next, especially as its former social insig-nia are replaced by the universal shroud: only the clergy were buried in their vestments, as we see in Holbein’s woodcut of the abbot where Death has pur-loined his victim’s mitre and crosier, or in some cadaver effigies such as those of Abbot Pierre Dupont (d. 1461) in Laon and Bishop Paul Bush (d. 1558) in Bristol.19 The reality after death was nonetheless the same for virtually every-one, viz. bodily decomposition in the grave.20 The ultimate distinction there is that, as Death sardonically reminds the Abbot in Lydgate’s poem, “Who that is fattest, I haue hym be-hight/In his graue shal sonnest putrefie” (lines 239–240), which matches the truism “Le plus gras est plus tot pourry” (line 184, “The fat-test rots soonest”) in the French poem.

The Characters and Their States of Mind in the ‘Danse Macabre’

The core message of the Danse Macabre was the moral warning about the need to be prepared for death at all times – a need that was underlined by the high death toll caused across all social strata by the Plague, which was to recur in virtually every generation for centuries to come. Those lucky enough to survive the epidemic or any other brush with death were usually left with an height-ened awareness of their own mortality – an awareness that apparently induced the Parisian poet Jehan le Fevre (c. 1320–c. 1390) to write his autobiographical poem Le respit de la mort in 1376. Yet the majority of people were far from ready to face death and may even have tried to forget about this ever lurking danger, thereby adopting a spiritually dangerous attitude of denial. Such a lack of readiness is what the Danse Macabre illustrates in order to change the men-tality and lifestyle of medieval readers and beholders.

Both in the French and in the English version, the Danse is being presented as a mirror in which all mankind may recognise themselves, from pope to peasant. In his prologue the French author or “docteur” explains how “En ce miroir chascun peut lire/Qui le conuient ainsy danser” (lines 9–10, “In this mirror everyone can read how he must dance thus”), which Lydgate translated as “In this myrrowre eueri wight mai fynde/That hym behoueth to go vpon this daunce” (lines 49–50). Medieval authors liked the metaphor of the mirror, as may be observed in the many texts that have the term Speculum in their title, such as the Speculum humanae salvationis.21 The mirror is, of course, the arche-typal tool in which one either sees a vain reflection of one’s own external appearance or may recognise one’s true self. The Danse offers both: on the one hand the grisly figures of the dead who act as mirroring counterparts to the living in the Danse, and on the other the living with all their sins, foibles and social pretensions, who are being presented as an alter ego with which the reader/beholder is meant to identify. The aim of the Danse is the shock of recognition that will persuade audiences to turn their thoughts to their own mortality and thus away from their earthly preoccupations.

The Danse is thus presented as a reflection of the condition and state of mind of the archetypal medieval nobleman, burgher, priest, peasant and child, to name but a few of its protagonists. Apart from a few exceptional characters whose stanzas once contained topical allusions to existing persons, as will be discussed in the next section, the characters in the Danse are all stereotypes whose words serve to convey a general moral warning. An example is the child who sombrely reflects that nobody may withstand God’s will and that “Aussy tot meurt jeune que vielx” (line 472, “A young man dies as soon as an old one”) – a truism that had its basis in the high infant mortality rates of the period, although not a sentiment that a mere child would ever be able to formulate himself.

The child’s resignation to his fate is matched by the pious sentiments expressed by the Carthusian and the hermit in both the French and the English Danse. Following the sentiments in the French poem, Lydgate’s Death praises

the Carthusian for his abstinence, which has left him with “chekes dede and pale” (line 345), and he urges him to submit patiently. The Carthusian needs no such exhortation as he is more than ready: “Vn to the worlde I was dede longe a-gon” (line 353), unlike the majority of mankind who fear to die. He thus commends his soul to God while reminding the reader that “Somme ben to dai that shul not be to morowe” (line 361), thereby underlining how sudden death may be. Similarly well prepared is the last character in the French and English Danse proper, the hermit, who likewise submits willingly to death after a life of abstinence and solitude. For this he is praised in a final stanza by Death, who in Lydgate’s text reminds the reader that “til to morowe is no man sure to abide” (line 632), echoing the aphorism by le mort in the French poem that “Il nest qui ait point de demain” (line 512, “There is nobody who has any tomorrow”). Death thus underlines for the reader or viewer the moral example of the her-mit: whereas few would have shared the abstinent lifestyle of a hermit they could at least strive to attain the same mental attitude towards death.

Yet the child, the Carthusian and the hermit are the exceptions in the Danse, not just in their attitudes, but also because they have either no social status of their own (the child) or because they have turned their back on society. All other participants are still too obsessed with rank, possessions and earthly pleasures to spare a thought for their own mortality and salvation. While this might be considered as normal human behaviour by modern standards, to medieval moralists such a frame of mind was sinful and indicative of human folly. The burgher is one of those who is explicitly reprimanded for being a materialistic fool, having failed to use his wealth for good causes in order to benefit his soul: it cannot now be used to stave off Death and will merely pass to a new owner, at least for a short while. A wise man recognises the tran-sience of earthly possessions whereas “Fol est qui damasser se bleche,/On ne scet pour qui on amasse” (lines 231–232, “A fool is he who harms himself by hoarding. One never knows for whom one hoards”), as Death reminds the burgher, whose own concluding truism is strikingly apt, “Cheulx qui plus ont plus enuis meurent” (line 240, “Those who have more are also more reluctant to die”).

Spiritual blindness through greed was a common topos in medieval culture and beyond.22 Money and possessions were essential to enjoy a secure position in society, and it was only near death that testators felt the need to divest themselves of their wealth with bequests to pay for prayers and masses. The ultimate fool in this respect, and also a medieval hate-figure, is the usurer, who is literally accused of blindness in the French poem: “Dusure est[es] tout auugle/Que dargent gaingnier tout ardes” (lines 323–324, “You are so blinded by usury that you burn entirely with desire to make money”). The theme of blindness is even continued in the usurer’s own final line, “Tel a biaux yeux qui ne voit goutte” (line 336), which Lydgate translated as “Somme haue feyre yȝen that seen neuer a dele” (line 408). The usurer in the French Danse and in Lydgate’s poem is unusual in being accompanied by a poor man, to whom he still tries to offer a loan when he is at the point of death: all other characters in the Danse face death all alone. A century later Holbein was to design a wood-cut of a rich man alone in a fortified chamber surrounded by treasures, who watches in horror as Death takes hold of a pile of coins. Yet this Renaissance woodcut is part of a much older tradition of moralistic warnings on the theme of “you cannot take it with you” or “shrouds have no pockets,” and whereas that might nowadays be taken as an incitement to enjoy life and its riches – mindful of the motto carpe diem – in medieval culture the message was to renounce such vain pleasures and focus instead on the life hereafter.

Greed is a sin – and a folly – that affects not only the secular characters in the Danse. If the Carthusian and the hermit are blessedly free from greed, not so the other representatives of the church in the Danse. The patriarch in Lydgate’s poem confesses to having been deceived by “Worldly honowre, grete tresowre and richesse” (line 129), while the cardinal has indulged himself with “vesture of grete coste” (line 94), the archbishop regretfully bids adieu to “my tresowr, my pompe & pride also” (line 166), and the bishop is likewise reminded by Death of “ȝowre riches […] ȝowre tresowre […] ȝowre worldli godes” (lines 202–204). All are thus shown to be dying in a state of sin as they still focus too much on the earthly rewards of their position in society, their repentance coming too late to make a difference now that Death has arrived for them unawares. Even among the lower ranks of the clergy sin abounds. The parson, bent on earning an income off the living and the dead alike through tithes and offerings, is about to learn that there is a price to pay for such venality. These examples illustrate the perceived state of disorder in medieval society where hardly anyone is free from sin, not even those charged with the spiritual welfare of their flocks. The Danse thus emphasises the universal human aptitude for sin and venality, whatever one’s social position.

Things are no better within the walls of the cloister where the clergy should have the benefit of seclusion from the world and its temptations. Despite having spent his days in a place of beauty and devotion, the monk confesses belatedly to have sins on his conscience for which he has not done penance yet (lines 316–318):

Or aige comme fol & niche,

Ou tamps passe commis maint vice,

De quoy nay pas fait penitanceBefore now I, foolish and naive,

Committed many a vice in the past,

For which I have not done penance

Little better is the cordelier or Franciscan friar, who used to make a living out of preaching about death and who thus should not now find himself surprised by the Death’s summons. Yet although the friar is not specific about his sins, he too is evidently not ready to die: “Mendissite point ne maseure,/Des meffais fault paier ladmende” (lines 453–454, “Begging gives me no certainty. Of my misdeeds I must pay the price”).

If even the clergy are mentally and spiritually ill-prepared for death, what hope is there for the secular representatives in the Danse? The most obvious person to welcome death as a release from a life of toil and deprivation is the laboureux or peasant, as Death himself points out with seeming empathy: “Laboureux qui en soing et painne/Aues vescu tout vostre tamps […] De mort deues estre contents,/Quar de grant soing vous deliure” (lines 425–426, 429–430, “Labourer, who in care and toil have lived all your days […] You must be content with Death for he will deliver you from great care”). Yet Death’s assumption that the peasant will be grateful for his release proves false: even though the poor drudge previously often desired death, now that his time has come he would prefer to stay alive, even if it means more toil in all weathers. Thus the will to live proves stronger, even among the down-trodden who might be expected to welcome death as a way out of their misery but who prefer to cling to life. In contrast to the modern perception of the Middle Ages as a period obsessed with death, the participants in the medieval Danse Macabre are instead presented as obsessed with life and all its pleasures, and oblivious of the memento mori warning. In fact, this is hardly surprising for the natural reaction to mortal threats like the Plague is not morbidity but denial, self-indulgence, dancing and revelry: to enjoy life while you can, or carpe diem. The Danse Macabre is not a reflection of morbid attitudes in everyday life, but a response by moralists and the church to such frivolous, worldly attitudes.23 The idea of dancing – a worldly pastime that appealed to all classes – is thus perverted to deliver a grim moralising warning.

Irresponsible living without a thought for one’s own mortality is abundantly clear in the younger generation, who are especially fond of dancing. According to the age-old tradition of the Ages of Man, a widespread theme in medieval culture, the age group of Adolescentia or Iuventus equalled the period of testosterone-driven young manhood: in some schemes this age group equals the months of April or May – the archetypal season of courtship in the love lyrics of the period.24 In the physiological tradition of the four elements and humours, youth is matched with red choler, the element of fire, and the season of summer, its qualities being hot and dry. It is this same age group that is traditionally the focus of the Legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead. In contrast, the hermit is a rather phlegmatic character, as befits his age in life: old age was associated with phlegm, the element of water, and the season of winter, its qualities being cold and moist.25 It is in part this which enables the hermit to accept death almost with equanimity.

Nowhere near as phlegmatic as the humble hermit is the celibate young clerk, who had confidently been hoping to live long enough to make a good career, his work rather than youthful frivolities being his prime pleasure as befits a member of the clergy: Marchant’s woodcut shows him with a tonsure. In contrast, the focus of the young squire was evidently on amorous pursuits in accordance with the typical behaviour of his age. Death openly mocks him, reminding him of his love of dancing with more attractive partners, as well as of his military prowess, but it is to mirth, pleasure, beauty and the ladies that the squire regretfully pays his farewells, thereby underlining his social status. With at least some thought for those he will come after him, he leaves them with a memento mori warning that beauty is but transient and that the soul is more important (lines 173–176):

Penses de lame qui desire

Repos, ne vous challe plus tant

Du corps que tous les jours empire;

Tous fault [m]ourir on ne scet quant.Think of the soul which desires

Rest, and do not worry yourself so much

About your body, which deterio-rates every day;

All must die – one does not know when.26

The most typical representative of this age group, however, is the lover or amoureux, or amorous squire, as Lydgate dubs him. He has no specific profession or rank, although his appearance in Marchant’s woodcut suggest wealth and status. The French poem presents the amoureux as young, noble, handsome, and utterly frivolous: instead of expressing concern for his soul, he spends his last breath on saying adieu to his hats, flowers, fellow-lovers and girlfriends: “Adieu chappiaux, boques, fleurettes/Adieu amans et puchelettes” (lines 372–373). Not surprisingly, Death points out to him the price for this fool-ish preoccupation with life’s vanities: “Le monde laires en dolour;/Trop laues ame, chest foleur” (lines 364–365, “You will leave this world with anguish; you have loved it too much, which is folly”). In his response the amoureux begs his former fellows to remember him and learn from his example (lines 374–376):

Souuiengne vous de moy souuent,

Et vous mires, se sages estes;

Petite pluye abat grant vent.May you remember me often,

And reflect, if you are wise;

A little rain can abate a strong wind.

Like the wind, the young lover is ultimately ephemeral, likely to be blown away into nothingness.

Lydgate’s amerous squyere (amorous squire) is likewise, as Death puts it, “Lusti fre of herte and eke desyrous […] But al shal turne in to asshes dede” (lines 435, 438).27 The amorous squire responds with the typical vainglory of youth that also characterises the verses of the French amoureux. Like any man with the vigour and blithe optimism of youth, he evidently never expected death to happen to him as he pursued women and pleasure. Like the Three Living before them, the squire and the lover are young nobles whose sole focus is on earthly enjoyment, arrogantly believing themselves too young and healthy to die: in the eyes of medieval moralists, they are thus guilty of the sin of pride as well as lust.

In a departure from the all-male French Danse, Lydgate chose to match his amorous squire with a gentilwoman amerous, one following the other. This amorous gentlewoman, who is also “of ȝeres ȝonge & grene” (line 449), proves to have been too obsessed with her own beauty to consider the thought that it might ever fade – or that her life itself might end even sooner, as she belatedly recognises in her final lines “But she is a fole shortli yn sentemente/That in her beaute is to moche assured” (lines 463–464). Death uses the term “straunge-nesse” (haughtiness or arrogance) to sum up the amorous gentlewoman’s atti-tude in life. The emblem of female vanity – often symbolised by a mirror – and the transience of beauty was to become a theme in its own right, with Death and the Maiden being one of its strands. In the Danse Macabre des Femmes the women are also often presented as vain and frivolous; a typical misogynistic stereotype.

Other sins abound in the Danse. If lust is the typical sin of youth, then glut-tony and greed were considered typical of the age of maturity. As we have seen, one archetypal sinner was the abbot, who according to medieval tradition liked to indulge himself too much. Of course, many readers of a different status in life would have been able to recognise their own fallibility in the abbot’s gluttony. Anger is another recognisable sin.28 The sergeant appears young and may suffer from too much red choler, but his resistance is futile, just like his mace, as Death tells him in the French poem (lines 288–290):

Sergent qui porties celle mache,

Il samble que vous rebelles;

Pour nient faictes la grimacheYou, Sergeant, who carry that mace,

It seems that you are in rebellion;

To no avail do you make that grimace.

The Constable is likewise a warrior, and thus ruled by aggression and red choler (or testosterone), forcing Death to warn him that (lines 101–102):

Rien ny vault chere espointable

Ne forche ne armures en cest assaultFrightening countenance does not help

Nor force or armour in this attack.

However, the prime sin displayed by several characters in the Danse is pride, whether the female vanity and arrogance of Lydgate’s amorous gentlewoman or the indignation of the sergeant who asks in vain, “Moy qui suis royal officier,/Comment mose la mort frapper?” (lines 297–298, “I am a royal officer, so how dare Death strike me?”). The pride of the king is evident in his lament “Helas, on peut veor & penser/Que vault orgueil, forche, lignage” (lines 75–76, “Alas, one can see and consider what pride, power and lineage are really worth”). For many medieval moralists pride was the root of all evil. Ironically the worst case of pride is probably the pope. The mock courtesy with which le mort in the French poem invites the pontiff to start the dance, “Aus grans maistre est deu lonneur” (line 24, “Honour is due to the great lords”), is nothing compared to the pope’s own opinion of himself: “Hees, fault il que la danse mainne/Moy premier qui suis dieu en terre?” (lines 25–26, “Alas, must I lead the dance in first place; I who am God on earth?”). It seems a clear case of anti-papal satire, which is not surprising at this particular moment in time: the Papal Schism (1378–1417), which had its origins in the move of the papacy from Rome to Avignon in 1309, had led in due course to the election of two rival popes and then in 1409 the election of a third anti-pope at the Council of Pisa in a failed attempt to resolve the crisis. To say that the coexistence of first two and then three rival popes undermined the authority of the papacy would be an understatement, and memories of the Schism must still have been fresh by the time the mural in Paris was completed in 1425. Yet this satirical take on the papacy is not the only topical allusion in the Danse to a state of disorder that occupied people’s minds in both France and England at this time.

The ‘Danse Macabre’ as an Expression of National Trauma

As stated earlier, the Danse Macabre did not just deliver a moral and social message to the individual. Even though these are its most obvious aspects, they do not explain why the Danse suddenly attained such popularity in the mid-1420s. After all, there were many other such moralising texts and themes of a “macabre” nature current in this period, such as the Legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead. Instead it was probably due to historical circumstances – a national trauma – that the Danse suddenly captured the imagination after having been around for at least half a century without attracting such notice.

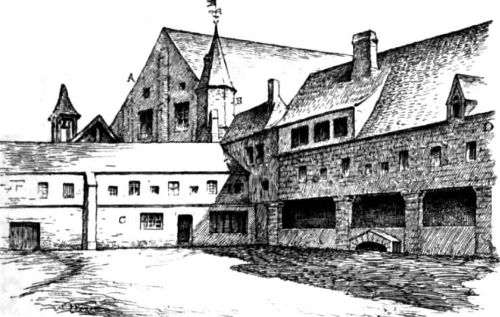

Nothing is known about the author of the French text: it may have been Jehan le Fevre, for in his 1376 poem Le respit de la mort he included the line “Je fis de Macabré la dance” (“I made the Dance of Macabré”) without any explanation, apparently confident that his readers would recognise this allusion.29 If so, his Danse Macabre poem must predate 1376. It was then adapted decades later to suit the purposes of the unknown patron who commissioned the mural inside the cemetery of Les Saints Innocents in the heart of Paris, which is said to have been started in August 1424 and finished in Lent 1425.30 Only then did the Danse truly begin its spread throughout France and across the Channel into England. Soon after its completion the Paris scheme inspired the Middle English adaptation written by Lydgate in 1426. His Dance of Death was in its turn incorporated in a cycle of paintings along the walls of Pardon Churchyard at Old St Paul’s Cathedral in London, probably around 1430.

The circumstances surrounding the creation of the first recorded Danse Macabre mural in Paris are highly significant. Far from being just a straightfor-ward morality about the inevitability of death, the Danse mural that was created in Paris at that precise time would have struck a chord with contemporaries because of its political allusions. The year 1422 had seen the deaths of two kings in quick succession: on 21 October the French king Charles VI, predeceased on 31 August by his son-in-law and chosen successor Henry V, king of England and victor of the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. At least Charles VI had been ailing for years whereas Henry V, whose demise at such a relatively young age was unexpected, had been able to make alterations to his will and prepare himself for death on his final sickbed, thereby dying a “good death” in accor-dance with the Ars Moriendi (“The Art of Dying”) literature of the period.31 Yet to contemporaries Henry seemed almost invincible and too young to die, and his loss was an unmitigated disaster.

Despite the warnings of moralists to be prepared for death at all times, the impact of these two kings’ deaths on their subjects was huge. Both countries were to remain without a crowned king for several years, for the official heir to both thrones – Henry V’s infant son Henry VI, who was born in 1421 to his French wife, Charles VI’s daughter Katherine – was far too young to be crowned; the boy-king’s uncle John, Duke of Bedford, would instead rule France as Regent on his behalf, while political rivals battled each other in England for control of government there. Meanwhile, the Dauphin Charles (Charles VI’s last surviving but disinherited son) still fought for his rights while living as an exile in the so-called kingdom of Bourges. It was only in 1429 that he was finally crowned king of France, thanks to the intervention of Joan of Arc, but even then it would take years before he gained control of Paris and of the French territories still remaining in English hands. This was a traumatic time for the divided kingdom of France and its inhabitants, for the interregnum after Charles VI’s death was no mere political crisis but one that went against the divine order: a kingdom needed a crowned king with a rightful claim to the throne, and the Dauphin had been disowned by his parents after his implica-tion in the murder in 1419 of John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy. Although he had been suffering from intermittent bouts of insanity since 1392, Charles VI had been a symbol of national unity at a time of civil war and foreign invasion; he was also the longest reigning French king, for he had succeeded his father in 1380. His death in 1422 left a void that was felt deeply by all his subjects; it helps explain why a teenage girl from rural Domrémy in Lorraine saw it as her mis-sion to restore order to the kingdom by bringing about the coronation of the Dauphin as France’s rightful king.

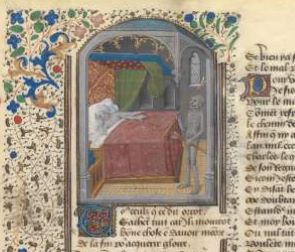

It is thus telling that the French Danse Macabre contains not one king, but two. The first king is ranked among the living, dressed in a mantle decorated with fleurs-de-lys and holding the royal sceptre, as we can still see in two early manuscript illuminations and in the woodcut published by Guy Marchant in 1485.32 The words of the king in the poem would also have struck a chord with contemporaries, for the lines “Je nay point apris a danser/A danses & nottes si sauuage” (lines 73–74, “I have never learnt to dance to such savage dances and tunes”) and “En la fin fault deuenir cendre” (line 80, “In the end we must turn into ashes”) contain unmistakable references to the notorious bal des sauvages (ball of the wildmen) in 1393 when the king was nearly burnt to death – an incident described in detail in Jean Froissart’s Chroniques.33 There is every reason to believe that this figure of the king in the mural was intended as a portrait of the late Charles VI, whose funeral procession with the first ever French occurrence of a lifelike funeral effigy had passed along the cemetery on its way to Saint-Denis, causing outbursts of grief among the crowds who lined the streets.34 These allusions are reinforced by the interpolated figure of the dead king (“vng roy mort”) at the end of the Danse, who describes himself as having now become mere food for worms whereas he was once a crowned king (“Sy aige este rois couronnes,” line 518). This reflection about his former state echoes the greeting of le mort to the still living king towards the start of the poem, “Venes, noble roy couronnes” (line 65, “Come, noble crowned king”). Contemporaries who beheld the mural and read the accompanying verses in the 1420s could not help but remember the anomalous state of France, bereft of its crowned and anointed king.

It is these allusions to the dead king Charles VI and the state of the kingdom that may help explain the huge and immediate impact of the mural. Whereas there is no evidence of the Danse Macabre between its earliest recorded mention by le Fevre in 1376 and the completion of the Parisian mural in 1425, Lydgate’s Middle English adaptation the following year is but one example of the sudden dissemination of the theme. Several extant manuscript copies of the French text can be dated to the later 1420s, visitors and locals record the existence of the mural in the cemetery, and at least two books of hours pro-duced in Paris around 1430–1435 feature a Danse Macabre cycle as a marginal decoration. During the harsh winter of 1434–1435 a “dansse machabre” was even sculpted in snow in the streets of Arras – the town where a treaty would be concluded in 1435 between the former Dauphin (now King Charles VII) and Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, which would result in the expelling of English troops from Paris in 1436 and eventually from all of France.35

Lydgate must have been aware of the references to Charles VI in the French Danse Macabre for he included allusions to the late Henry V in his own Middle English adaptation. First of all, he added his own introductory stanzas or “Verba Translatoris,” of which the second with its lament about the fall of kings and conquerors at the height of their power and felicity reads like an elegy for Henry V; the final line “Fortune hath hem from her whele [y]throwe” (line 16) even conjures up the iconic image of the Wheel of Fortune from which kings are cruelly toppled. Secondly, Lydgate introduced a new character, “Maister Jon Rikelle some tyme tregetowre/Of nobille harry kynge of Ingelonde/And of Fraunce the myghti Conquerowre” (lines 513–515). This tregetour or magician is not only a rare instance of a named character in the medieval tradition of the Danse, but the interpolation of this stanza also enabled the poet to name the late lamented king Henry V whose glorious conquests and premature death would continue to haunt the English psyche for centuries to come, especially as the country descended into a state of political disorder and civil war that would last until the Tudor era.36

The topical allusions to two dead kings and the trauma felt by two nations may explain the rapid impact of the Danse Macabre on both sides of the Channel in the mid to late 1420s. By the time political order had been restored in France after the coronation of Charles VII, the treaty between the king and the Duke of Burgundy, and the expulsion of the English from Paris and the rest of the country, the original allusions to Charles VI in the Parisian Danse would have been gradually forgotten. In England new textual variants of Lydgate’s poem omitted the “Verba Translatoris” with their references to the fall of kings and conquerors as well as the stanzas about Henry V’s tregetour Jon Rikelle, thereby removing topical allusions that were probably no longer considered relevant at the time of these “revisions” of the poem.37 Even if historical circumstances in France and England provided the original impetus to the dissemination of the Danse, the oft discussed element of estates satire, which is particularly evident in the portrayal of church dignitaries such as the pope and the abbot, is likely to have been a major factor in its long-lasting success, especially in the Renaissance.38

Conclusion

Obviously, on a personal level anxiety about one’s own death or the loss of loved ones can cause melancholy, depression and other sorts of mental disorder, but to characterise the Middle Ages as a period in which fear of death was universal – and the Danse Macabre as a typical manifestation of this fear – is too simplistic. The fear that is expressed in the Danse is not of death itself or of the physical pain of dying, but of dying alone and unexpectedly in a state of sin, without the chance to confess one’s sins and receive absolution. In the traditional Danse death is a lonely, isolating experience. Apart from the usurer, each dying individual is on his own with only his dead counterpart for company: there is no priest, spouse, friend or relative to comfort and console him in his final hour, nor even a familiar setting, which is in stark contrast to the conventional deathbed scenes we find in medieval art or in the Ars Moriendi.39 The Danse thus paints the worst possible scenario for medieval Christians.

Yet if medieval Christians really lived their lives accordingly, mindful of these moral warnings, in constant fear of death and renouncing all earthly indulgences, the spiritual and social order would have been ensured and there would have been no need of such poems, murals or moralities. The reality was, of course, that few people matched the ideal of the Carthusian or the hermit in the Danse, who have already renounced society; if they did, there would be no need for such a plethora of moral warnings. In fact, the Danse may even have had the opposite effect of confirming to readers and viewers that they were not alone in their focus on life rather than on death, and that such a state of mind – even if sinful – was altogether human and normal.40 The very fact that depictions of the Legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead became increasingly violent over time also suggest that the Church and the moralists felt obliged to paint an ever more forceful picture in order to achieve the desired effect, viz. repentance and a more moral lifestyle.

At the same time, the Danse would have caused unease in contemporary viewers by emphasising that Death spares neither king nor pauper, and that social status with all its trappings is but ephemeral at the end of life’s journey: the wealthy few may be able to afford a sumptuous monument, but the body inside such a tomb is still only dressed in a shroud and ultimately subject to decomposition. One corpse is like another: there is no distinction in death, as Lydgate explained in a slightly later didactic poem, The Debate of the Horse, Goose, and Sheep, even if costly tomb monuments might appear to suggest otherwise:

Tweene riche & poore what is the difference,

Whan deth approchith in any creature,

Sauff a gay tumbe ffressh of apparence?41

Charles VI and Henry V in due course received their own splendid monuments once order had returned to their kingdoms. To contemporaries in Paris and London, however, the two Danse Macabre mural schemes served as a reminder that kings are no less impervious to death than ordinary – and somewhat less ordinary – mortals of all ages and from all walks of life.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Contribution (197-218) from Mental (Dis)Order in Later Medieval Europe, edited by Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Susanna Niiranen (Brill Academic Pub., 03.12.2014), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.