The history of the House of Saud reveals a monarchy sustained by a combination of religious alliance, oil wealth, political repression, and international patronage.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Since the founding of the modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932, the House of Saud has ruled as an absolute monarchy grounded in a fusion of dynastic authority, religious legitimacy, and control over oil revenues. Over the course of the twentieth century, petroleum wealth enabled the royal family to construct sprawling palaces, maintain global estates, and engage in conspicuous consumption, all while cultivating extensive patronage networks. This display of opulence stands in stark contrast to the growing economic pressures borne by ordinary Saudis in recent decades: reductions in public sector wages and allowances, increases in fuel and utility prices, the imposition of value-added taxes, and widening disparities in wealth.1 These measures reflect a deeper political economy in which lavish royal privilege is preserved at the expense of citizen welfare.

This essay contends that the ostentation of the Saudi ruling elite is not merely a cultural phenomenon but a deliberate strategy of governance. Extravagance reinforces dynastic prestige while austerity is framed as national necessity, thereby sustaining a system of authoritarian control. At the same time, the regime’s material inequality is underwritten by severe restrictions on civil liberties, the imprisonment of dissenters, the punishment of women’s rights activists, and the use of extrajudicial violence, most notoriously in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018.2 Such repression ensures that economic burdens remain unchallenged, while dissent against royal excess is curtailed.

What follows traces the historical formation of the House of Saud and its alliance with Wahhabi clerics; examines the transformation of oil wealth into a foundation for elite luxury; analyzes the impact of austerity measures on the Saudi public; and surveys the human rights abuses that reinforce this system. In doing so, it situates Saudi Arabia within broader debates about rentier monarchies, authoritarian resilience, and the contradictions of modernization under absolute rule.

Historical Origins of the House of Saud

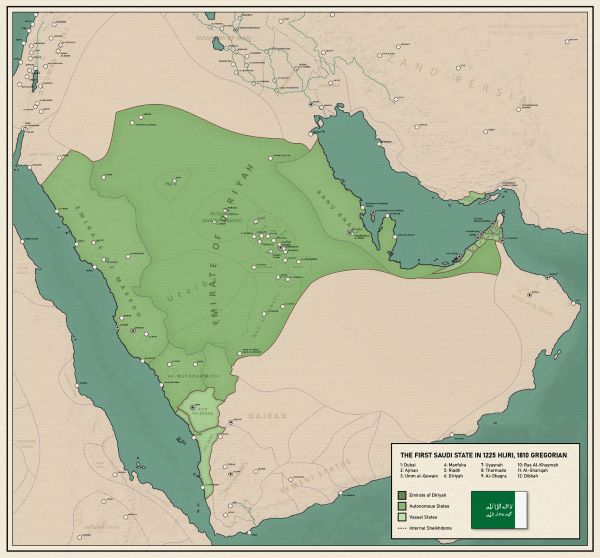

The roots of Saudi Arabia’s ruling dynasty stretch back to the mid-eighteenth century, when Muhammad ibn Saud, chief of the small oasis town of Dirʿiyya, formed an alliance with the religious reformer Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab.3 This pact united political authority with a puritanical interpretation of Islam, giving the Saud family religious legitimacy while providing Wahhabism with the protection of temporal power. The partnership not only enabled the creation of the First Saudi State (1744–1818) but also established a durable pattern in which dynastic survival was tied to clerical endorsement.4

The First Saudi State’s rapid territorial expansion across central Arabia and incursions into the Hijaz alarmed the Ottoman Empire, which regarded control of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina as central to its legitimacy as the seat of the caliphate. In response, Sultan Mahmud II dispatched his Egyptian viceroy, Muhammad Ali, to suppress the Saudi-Wahhabi insurgency. Ottoman-Egyptian forces eventually destroyed Dirʿiyya in 1818, captured members of the Saudi family, and executed key leaders, signaling the temporary end of the dynasty’s ambitions.5 Yet even in defeat, the Saudis retained a legacy of religious-political fusion that would resurface in subsequent revivals.

The Second Saudi State (1824–1891) emerged under Turki ibn ʿAbdallah, who re-established Saudi authority in Riyadh.6 However, unlike its predecessor, this iteration was plagued by instability and internecine rivalry. Tribal fissures, succession disputes, and the rise of the Al Rashid dynasty in Haʾil undermined Saudi dominance.7 The Rashidis, benefiting from Ottoman recognition and superior military organization, gradually eroded Saudi power, culminating in the defeat and exile of the Al Saud after the Battle of Mulayda in 1891.8 This Rashidi ascendancy underscored the fragility of Saudi authority in the absence of consolidated leadership and exposed the dynasty to oscillations between resurgence and decline.

The ultimate revival came under ʿAbd al-ʿAziz ibn Saud (Ibn Saud), who recaptured Riyadh in 1902 in a daring raid that marked the symbolic rebirth of the dynasty.9 His subsequent expansion across the Najd and eventual conquest of the Hijaz in 1925 consolidated a realm that would become the modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932. Critical to this success was Ibn Saud’s capacity to leverage both tribal loyalty and Wahhabi militancy, embodied in the Ikhwan, while navigating a shifting international context.10

The collapse of Ottoman authority during World War I and the growing strategic interests of Britain in the Gulf provided new opportunities. Ibn Saud secured British subsidies through treaties such as the 1915 Treaty of Darin, which recognized him as ruler of Najd and placed his territories under British protection.11 This patronage not only provided financial lifelines during the formative years of his expansion but also positioned him as a counterweight to rival claimants, including the Sharif of Mecca, who enjoyed Britain’s initial favor. By carefully balancing tribal alliances, clerical approval, and foreign sponsorship, Ibn Saud established a monarchy that was at once indigenous in its religious grounding and international in its diplomatic scaffolding.12

Thus, the House of Saud’s early history illustrates recurring themes of survival through alliances, with Wahhabi clerics, against Ottoman incursions, in rivalry with the Rashidis, and later in strategic partnership with Britain. These foundations would shape the kingdom’s later transformation under the discovery of oil, embedding authoritarian monarchy within both regional politics and global geopolitics.

Oil Wealth and Royal Extravagance

The discovery of oil in Saudi Arabia during the 1930s marked a watershed in the fortunes of the House of Saud. In 1933, Ibn Saud granted a concession to the Standard Oil Company of California (later Chevron), leading to the formation of the Arabian American Oil Company (ARAMCO).13 Initial revenues were modest, but by the 1950s and 1960s oil income had transformed the Saudi state into one of the most resource-rich regimes in the world. This rentier wealth allowed the monarchy not only to consolidate domestic authority through distribution of subsidies and patronage but also to indulge in unprecedented levels of luxury and conspicuous consumption.14

Royal extravagance became a defining feature of Saudi political culture. Palaces multiplied in Riyadh, Jeddah, and along the coasts; fleets of luxury cars, private jets, and yachts became commonplace among senior princes.15 Members of the royal family acquired estates in Europe and North America, reinforcing their global reach. The opacity of the state budget, in which vast sums were allocated for “royal allowances,” institutionalized this system of privilege.16 At the same time, the monarchy ensured loyalty through the direct distribution of stipends to thousands of princes, cementing internal cohesion within the sprawling family.

The political implications of this oil-financed luxury were profound. Rentier theory suggests that regimes reliant on unearned income from natural resources often avoid taxation, thereby reducing demands for political representation.17 In Saudi Arabia, this dynamic insulated the monarchy from popular pressure while enabling it to cultivate a patronage-based legitimacy: citizens were provided with free education, healthcare, fuel subsidies, and guaranteed public-sector employment. Yet this arrangement was deeply asymmetrical, as the scale of royal privilege far exceeded the benefits provided to the broader population.

Conspicuous consumption by the royals also had a symbolic dimension. Extravagance functioned as a visible marker of dynastic power, reinforcing perceptions of the king and senior princes as near-untouchable figures above ordinary citizens.18 At the same time, lavish spending abroad (on art auctions, London real estate, and global entertainment) provoked criticism of hypocrisy: a religiously conservative state funding hedonistic lifestyles in Western capitals.19

By the late twentieth century, Saudi oil wealth had entrenched a paradox: a society in which modernization projects, infrastructure development, and generous subsidies coexisted with extreme concentrations of wealth at the top. As oil revenues soared during the boom years of the 1970s, the monarchy became synonymous with both the material trappings of abundance and the political structures of absolute rule.20

Absolute Monarchy and Political Control

From its founding in 1932, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was structured as an absolute monarchy in which all ultimate authority resided with the king and his family. Unlike constitutional monarchies elsewhere, Saudi Arabia never developed representative institutions capable of constraining royal power.21 The Basic Law of 1992, introduced under King Fahd, reaffirmed the Qurʾan and the Sunna as the country’s constitution, placing sovereignty squarely in the hands of the ruling family.22

The Al Saud’s dominance extended across the political and administrative apparatus. Senior princes monopolized control of key ministries, including defense, interior, foreign affairs, and the national guard, ensuring that both the coercive and diplomatic levers of state power remained within family hands.23 The Shura Council, established in 1993, served only in an advisory capacity, with no legislative authority, its members appointed directly by the king.24 This arrangement preserved the façade of consultation while preventing genuine political pluralism.

Public dissent was systematically repressed. Political parties were outlawed, independent unions prohibited, and the press tightly controlled by both censorship and self-regulation.25 Intellectuals, clerics, and activists who challenged state policies faced harassment, detention, or exile.26 Even modest reform movements, such as the petition campaigns of the 1990s calling for greater political participation, were met with state crackdowns.27 The system thus relied not only on material patronage but also on coercive control to neutralize opposition.

The consolidation of power reached new levels under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) after 2015. While MbS projected himself as a modernizer through Vision 2030 reforms, he simultaneously concentrated authority by sidelining rival princes, centralizing decision-making, and extending surveillance capabilities through advanced technologies.28 The 2017 Ritz-Carlton purge, in which prominent businessmen and princes were detained under the guise of anti-corruption, exemplified both the ruthlessness and the arbitrariness of royal authority.29

The persistence of absolute monarchy in Saudi Arabia reflects a carefully maintained equilibrium: dynastic privilege, clerical endorsement, patronage, and coercion combined to sustain a system largely insulated from public accountability. At its core, the monarchy rests not on broad-based consent but on the intertwining of wealth, repression, and the absence of institutional checks, a formula that continues to define the kingdom’s political order.

Austerity for the Public

While the House of Saud has long enjoyed immense personal wealth, ordinary Saudi citizens have increasingly borne the costs of fiscal retrenchment. The collapse of oil prices in 2014 exposed the vulnerabilities of a state dependent on hydrocarbon rents.30 In response, the government initiated austerity measures that directly affected citizens’ daily lives, eroding the post-1970s social contract in which oil wealth had underwritten welfare, subsidies, and near-guaranteed public employment.

One of the most visible steps came in 2016 when the government reduced allowances and bonuses for public employees, effectively cutting salaries for a workforce that represented two-thirds of employed Saudis.31 Though some benefits were later restored following public backlash, the episode signaled a shift toward tighter fiscal discipline. At the same time, longstanding subsidies for fuel, electricity, and water were scaled back, leading to sharp increases in utility bills.32 For many households, accustomed to cheap services as a hallmark of citizenship, these cuts represented not only financial strain but also a symbolic breach of the monarchy’s distributive obligations.

The introduction of a value-added tax (VAT) in 2018, initially set at 5 percent and later tripled to 15 percent in 2020, further expanded the cost of living for ordinary Saudis.33 While justified as necessary for diversifying state revenue under the Vision 2030 program, the measure disproportionately affected middle- and lower-income families, as consumption taxes are inherently regressive.34 The state presented these policies as national sacrifices required to build a “post-oil” economy, yet critics noted that austerity coincided with continued royal extravagance and mega-projects such as the futuristic NEOM city.35

Unemployment, particularly among youth, compounded these pressures. Despite promises of reform, the private sector remained underdeveloped, and the state could no longer absorb all graduates into secure public jobs.36 Rising inequality, with royals and business elites shielded from the burdens imposed on ordinary citizens, deepened the sense of social frustration. The juxtaposition of austerity for the public and affluence for the ruling family highlighted the structural imbalance at the core of the Saudi political economy.

Human Rights Abuses and Repression

The authoritarian foundations of Saudi rule are reinforced not only by economic inequality but also by systematic violations of human rights. The kingdom’s legal and political framework leaves little space for freedom of speech, assembly, or association. Political parties remain banned, independent trade unions are prohibited, and demonstrations are routinely criminalized.37 Critics of the regime (whether journalists, clerics, or human rights defenders) face surveillance, arbitrary detention, and in some cases, execution.38

Women’s rights offer a telling example of the regime’s contradictory posture. While recent reforms under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman permitted women to drive and loosened aspects of the guardianship system, these measures were accompanied by the imprisonment and harassment of women activists who had campaigned for those very changes.39 Figures such as Loujain al-Hathloul endured detention, solitary confinement, and reports of torture, underscoring the regime’s intolerance of independent advocacy.40 In this way, liberalizing reforms were carefully staged as royal concessions, not as the result of grassroots mobilization.

The Saudi criminal justice system continues to employ corporal and capital punishment at some of the highest rates globally. Public executions, often by beheading, are used both for ordinary criminal offenses and for charges related to political dissent or alleged terrorism.41 In 2022 alone, the kingdom executed 81 men in a single day, many of them convicted after opaque trials criticized by international observers.42 Such spectacles of punishment serve both to deter opposition and to project the coercive authority of the monarchy.

Perhaps the most internationally visible instance of repression was the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018.43 A subsequent investigation by the United Nations Special Rapporteur concluded that Khashoggi’s death was a premeditated extrajudicial killing carried out by Saudi agents, with credible evidence implicating senior officials, including Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.44 While the killing drew global condemnation, the lack of meaningful accountability highlighted the degree to which international partnerships insulated the monarchy from repercussions.

Human rights violations thus remain integral to Saudi governance. They silence dissent, maintain the monarchy’s aura of unchallengeable authority, and ensure that economic burdens imposed on the public are met with minimal resistance. Far from isolated abuses, these practices form part of a systemic architecture of control, one that balances material patronage with coercion in sustaining absolute monarchy.

The Royal Paradox: Luxury vs. Austerity

The contrast between the House of Saud’s conspicuous affluence and the austerity imposed upon the general population is not incidental but central to the monarchy’s strategy of rule. While princes maintain fleets of private jets, superyachts, and multimillion-dollar estates abroad, ordinary Saudis are asked to sacrifice for the sake of fiscal responsibility and economic diversification.45 The paradox lies in the simultaneous pursuit of public belt-tightening and extravagant royal spending, a juxtaposition that reveals the asymmetry at the heart of the Saudi rentier system.

High-profile “giga-projects” such as the $500 billion NEOM megacity illustrate this contradiction. Officially promoted as part of Vision 2030 to modernize the economy and reduce dependence on oil, these projects also serve as showcases of royal ambition and extravagance, consuming vast sums of public resources.46 Meanwhile, austerity measures such as subsidy cuts, higher utility bills, and increased VAT directly strain household budgets. The symbolism is unavoidable: resources flow into futuristic desert cities while citizens contend with shrinking state benefits.

Royal privilege extends beyond domestic projects into the global arena. Reports of princes purchasing fleets of luxury cars, commissioning lavish weddings, and investing in foreign football clubs have attracted widespread attention.47 These expenditures, often financed through opaque state channels, highlight the disjunction between the rhetoric of national sacrifice and the reality of dynastic consumption. As Madawi al-Rasheed observes, the monarchy “projects modernization through spectacle while perpetuating inequality through austerity.”48

At the same time, the regime uses spectacle strategically to deflect criticism. International sporting events, entertainment festivals, and high-profile cultural initiatives are designed to recast Saudi Arabia as a dynamic, modernizing power.49 Domestically, these spectacles provide distraction and entertainment, creating a carefully managed release valve for social frustrations. Yet the authoritarian underpinnings remain intact, with surveillance, repression, and patronage ensuring that opposition to the underlying imbalance remains muted.

The royal paradox is thus both economic and political. Luxury sustains dynastic legitimacy by signaling strength and abundance, while austerity disciplines the population into accepting the monarchy’s terms. Together, they form a dual strategy of survival: one dazzling in its display, the other coercive in its imposition.

International Relations and Complicity

The survival of the House of Saud has always depended not only on domestic control but also on international alliances, particularly with Western powers. Since the discovery of oil, the monarchy has positioned itself as a key partner to the United States and Europe, trading energy security for military protection and diplomatic cover.50 This arrangement ensured that Saudi human rights abuses, authoritarianism, and economic inequalities often faced muted international criticism in light of strategic interests.

The U.S.-Saudi partnership, initiated in the 1930s with the ARAMCO concession and formalized in 1945 when King ʿAbd al-ʿAziz met President Franklin D. Roosevelt aboard the USS Quincy, laid the foundations for decades of cooperation.51 The kingdom’s role as the world’s largest oil exporter and a crucial swing producer in OPEC cemented its importance during the Cold War and beyond. In return, Washington provided arms sales, military training, and security guarantees.52 The relationship was further strengthened after 1991, when the Gulf War brought U.S. troops to Saudi soil, symbolizing the kingdom’s reliance on American power for external security.

European states, too, have profited from the Saudi alliance, particularly through lucrative arms contracts. The United Kingdom, for example, maintained deep ties via the Al-Yamamah arms deal, the largest export agreement in British history.53 Such deals continued even amid international outcry over civilian casualties in Yemen, where Saudi-led airstrikes, backed by Western-supplied weapons, contributed to one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises.54

This external support has functioned as a shield against accountability. The murder of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 drew temporary condemnation from Western governments, yet arms sales resumed and diplomatic relations normalized within a short period.55 Even as human rights organizations documented abuses, from mass executions to the imprisonment of activists, geopolitical calculations and economic interests routinely outweighed calls for reform.56

In effect, the monarchy’s lavish domestic privilege and authoritarian governance are sustained not only by oil rents and internal repression but also by the complicity of powerful international partners. The global order thus underwrites Saudi authoritarianism: Western states benefit from energy and arms contracts, while the monarchy enjoys protection from significant external pressure. This symbiosis illustrates the extent to which the House of Saud’s endurance is as much a product of global geopolitics as of domestic control.

Conclusion

The history of the House of Saud reveals a monarchy sustained by a combination of religious alliance, oil wealth, political repression, and international patronage. From its eighteenth-century partnership with Wahhabi clerics to its twentieth-century oil bonanza, the dynasty has consistently leveraged resources and alliances to entrench its rule. The paradox at the heart of the kingdom is stark: while the royal family indulges in extraordinary luxury, the broader population has faced periods of austerity marked by subsidy cuts, wage reductions, and rising living costs. These economic sacrifices, framed as essential for modernization, coexist with an authoritarian system that silences dissent and perpetuates structural inequality.

At the same time, Saudi Arabia’s human rights record underscores the coercive mechanisms by which the monarchy preserves its dominance. The imprisonment of activists, systematic restrictions on speech and association, and public spectacles of capital punishment exemplify a governance model rooted in repression. High-profile incidents such as the murder of Jamal Khashoggi reveal not anomalies but symptoms of a wider pattern of authoritarian excess.57

International complicity further reinforces this system. Strategic partnerships with the United States, the United Kingdom, and other Western states have provided diplomatic cover and military support, ensuring that geopolitical and economic interests consistently outweigh concerns for rights or accountability.58 In this way, the endurance of the House of Saud reflects not merely domestic control but also the enabling structures of the global order.

Taken together, the lavish consumption of the royal family, the austerity imposed on the public, the machinery of repression, and the protection afforded by international allies form a single architecture of survival. It is an architecture that maintains the privileges of a dynastic elite while subordinating the welfare and freedoms of the citizenry. Whether this arrangement can endure in the long term (amid economic diversification, demographic pressures, and shifting global energy markets) remains uncertain. Yet the history traced here makes clear that the kingdom’s present contradictions are the product of deeply entrenched patterns, unlikely to be undone without fundamental political transformation.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Steffen Hertog, Princes, Brokers, and Bureaucrats: Oil and the State in Saudi Arabia (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), 55–63; International Monetary Fund, Saudi Arabia: Selected Issues (Washington, D.C.: IMF, 2017), 12–15.

- Human Rights Watch, World Report 2019: Saudi Arabia (New York: HRW, 2019), 4–6; United Nations Human Rights Council, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions: Investigation into the Unlawful Death of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi” (Geneva: UNHRC, 2019).

- Alexei Vassiliev, The History of Saudi Arabia (London: Saqi Books, 2013), 53–57.

- Madawi al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 15–22.

- William Ochsenwald, Religion, Society, and the State in Arabia: The Hijaz under Ottoman Control, 1840–1908 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1984), 32–36.

- Joseph A. Kechichian, Succession in Saudi Arabia (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 8–13.

- J. E. Peterson, Historical Dictionary of Saudi Arabia (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2003), 33–35.

- Alexei Vassiliev, The History of Saudi Arabia, 221–225.

- Robert Lacey, The Kingdom (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981), 92–96.

- Madawi al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 49–54.

- Frederick Anscombe, The Ottoman Gulf: The Creation of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 162–167.

- Nadav Safran, Saudi Arabia: The Ceaseless Quest for Security (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), 61–65.

- Robert Vitalis, America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), 45–49.

- Steffen Hertog, Princes, Brokers, and Bureaucrats: Oil and the State in Saudi Arabia (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), 72–78.

- Thomas Lippman, Inside the Mirage: America’s Fragile Partnership with Saudi Arabia (Boulder: Westview Press, 2004), 101–104.

- Pascal Menoret, Joyriding in Riyadh: Oil, Urbanism, and Road Revolt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 23.

- Giacomo Luciani, “Allocation vs. Production States: A Theoretical Framework,” in The Rentier State, ed. Hazem Beblawi and Giacomo Luciani (London: Croom Helm, 1987), 63–82.

- Madawi al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 115–118.

- Rachel Bronson, Thicker than Oil: America’s Uneasy Partnership with Saudi Arabia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 89–91.

- Alexei Vassiliev, The History of Saudi Arabia (London: Saqi Books, 2013), 351–356.

- Madawi al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 150–155.

- Basic Law of Governance, Royal Decree A/90, March 1, 1992.

- Joseph A. Kechichian, Succession in Saudi Arabia (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 57–63.

- Vali Nasr, “The New Balance of Power in the Middle East,” Revista de Prensa (June 10, 2025).

- Human Rights Watch, Saudi Arabia: Freedom of Expression and Association under Threat (New York: HRW, 2004), 2–6.

- Thomas Hegghammer, “Islamist Violence and Regime Stability in Saudi Arabia,” International Affairs 84, no. 4 (2008): 701–715.

- Stéphane Lacroix, Awakening Islam: The Politics of Religious Dissent in Contemporary Saudi Arabia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 233–237.

- Yasmine Farouk, “The Saudi Kingdom’s Vision 2030,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 2016.

- Ben Hubbard, MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed bin Salman (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2020), 132–138.

- International Monetary Fund, Saudi Arabia: 2015 Article IV Consultation—Staff Report (Washington, D.C.: IMF, 2015), 7–10.

- Ben Hubbard, “Saudi Arabia Slashes Ministers’ Pay, Cuts Perks for Public Employees,” New York Times, September 27, 2016.

- Steffen Hertog, “Challenges to the Saudi Distributional State in the Age of Austerity,” Carnegie Middle East Center, April 2017.

- “Saudi Arabia Raises VAT to 15%,” BBC News, May 11, 2020.

- Adam Hanieh, Money, Markets, and Monarchies: The Gulf Cooperation Council and the Political Economy of the Contemporary Middle East (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 192–196.

- Madawi al-Rasheed, The Son King: Reform and Repression in Saudi Arabia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 78–83.

- International Labour Organization, Youth Employment in the Middle East and North Africa: Saudi Arabia Country Report (Geneva: ILO, 2019), 14–18.

- Amnesty International, Saudi Arabia 2021: Human Rights in the Middle East and North Africa Review (London: Amnesty International, 2022), 238–242.

- Human Rights Watch, World Report 2022: Saudi Arabia (New York: HRW, 2022), 497–502.

- Madawi al-Rasheed, The Son King: Reform and Repression in Saudi Arabia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 65–69.

- Amnesty International, Saudi Arabia: Free Women’s Rights Defenders (London: Amnesty International, 2019).

- Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide, Death Penalty Database: Saudi Arabia, accessed September 2025.

- “Saudi Arabia Executes 81 Men in a Single Day,” Al Jazeera, March 12, 2022.

- Krishnadev Calamur, “Saudi Arabia’s Shifting Narrative on Jamal Khashoggi’s Killing,” The Atlantic (October 26, 2018).

- United Nations Human Rights Council, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions: Investigation into the Unlawful Death of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi” (Geneva: UNHRC, 2019), 4–6.

- Ben Hubbard, MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed bin Salman (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2020), 145–149.

- Yasmine Farouk, “Vision 2030 and the Politics of Saudi Megaprojects,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 2019.

- David B. Ottaway, The King’s Messenger: Prince Bandar bin Sultan and America’s Tangled Relationship with Saudi Arabia (New York: Walker & Co., 2008), 214–218.

- Madawi al-Rasheed, The Son King: Reform and Repression in Saudi Arabia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 81.

- Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, The Politics of Vision 2030: Saudi Arabia’s Transformation and the Gulf’s Future (London: Hurst, 2021), 54–59.

- Bruce Riedel, Kings and Presidents: Saudi Arabia and the United States since FDR (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2018), 3–7.

- Rachel Bronson, Thicker than Oil: America’s Uneasy Partnership with Saudi Arabia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 42–46.

- F. Gregory Gause III, The International Relations of the Persian Gulf (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 112–117.

- Mark Phythian, The Politics of British Arms Sales since 1964 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), 129–134.

- Human Rights Watch, World Report 2020: Saudi Arabia (New York: HRW, 2020), 511–515.

- United Nations Human Rights Council, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions: Investigation into the Unlawful Death of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi” (Geneva: UNHRC, 2019), 6–8.

- Amnesty International, The State of the World’s Human Rights: Saudi Arabia 2020/2021 (London: Amnesty International, 2021), 493–498.

- Human Rights Watch, World Report 2019: Saudi Arabia (New York: HRW, 2019), 6–9.

- Bruce Riedel, Kings and Presidents: Saudi Arabia and the United States since FDR (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2018), 182–187.

Bibliography

- Al-Rasheed, Madawi. A History of Saudi Arabia. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- ———. The Son King: Reform and Repression in Saudi Arabia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Amnesty International. Saudi Arabia 2021: Human Rights in the Middle East and North Africa Review. London: Amnesty International, 2022.

- ———. Saudi Arabia: Free Women’s Rights Defenders. London: Amnesty International, 2019.

- ———. The State of the World’s Human Rights: Saudi Arabia 2020/2021. London: Amnesty International, 2021.

- Anscombe, Frederick. The Ottoman Gulf: The Creation of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

- BBC News. “Saudi Arabia Raises VAT to 15%.” May 11, 2020.

- Bronson, Rachel. Thicker than Oil: America’s Uneasy Partnership with Saudi Arabia. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Calamur, Krishnadev, “Saudi Arabia’s Shifting Narrative on Jamal Khashoggi’s Killing,” The Atlantic (October 26, 2018). https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/10/saudi-jamal-khashoggi-narrative/574111/.

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Farouk, Yasmine. “The Saudi Kingdom’s Vision 2030.” March 2016.

- ———. Farouk, Yasmine. “Vision 2030 and the Politics of Saudi Megaprojects.” October 2019.

- Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide. Death Penalty Database: Saudi Arabia. Accessed September 2025.

- Gause, F. Gregory III. The International Relations of the Persian Gulf. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Hanieh, Adam. Money, Markets, and Monarchies: The Gulf Cooperation Council and the Political Economy of the Contemporary Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Hegghammer, Thomas. “Islamist Violence and Regime Stability in Saudi Arabia.” International Affairs 84, no. 4 (2008): 701–715.

- Hertog, Steffen. Princes, Brokers, and Bureaucrats: Oil and the State in Saudi Arabia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010.

- ———. “Challenges to the Saudi Distributional State in the Age of Austerity.” Carnegie Middle East Center, April 2017.

- Hubbard, Ben. MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed bin Salman. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2020.

- ———. “Saudi Arabia Slashes Ministers’ Pay, Cuts Perks for Public Employees.” New York Times, September 27, 2016.

- Human Rights Watch. Saudi Arabia: Freedom of Expression and Association under Threat. New York: HRW, 2004.

- ———. World Report 2019: Saudi Arabia. New York: HRW, 2019.

- ———. World Report 2020: Saudi Arabia. New York: HRW, 2020.

- ———. World Report 2022: Saudi Arabia. New York: HRW, 2022.

- International Labour Organization. Youth Employment in the Middle East and North Africa: Saudi Arabia Country Report. Geneva: ILO, 2019.

- International Monetary Fund. Saudi Arabia: 2015 Article IV Consultation—Staff Report. Washington, D.C.: IMF, 2015.

- ———. Saudi Arabia: Selected Issues. Washington, D.C.: IMF, 2017.

- Kechichian, Joseph A. Succession in Saudi Arabia. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

- Lacroix, Stéphane. Awakening Islam: The Politics of Religious Dissent in Contemporary Saudi Arabia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Lacey, Robert. The Kingdom. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981.

- Lippman, Thomas. Inside the Mirage: America’s Fragile Partnership with Saudi Arabia. Boulder: Westview Press, 2004.

- Luciani, Giacomo. “Allocation vs. Production States: A Theoretical Framework.” In The Rentier State, edited by Hazem Beblawi and Giacomo Luciani, 63–82. London: Croom Helm, 1987.

- Menoret, Pascal. Joyriding in Riyadh: Oil, Urbanism, and Road Revolt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Nasr, Vali, “The New Balance of Power in the Middle East,” Revista de Prensa (June 10, 2025). https://www.almendron.com/tribuna/the-new-balance-of-power-in-the-middle-east/.

- Ochsenwald, William. Religion, Society, and the State in Arabia: The Hijaz under Ottoman Control, 1840–1908. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1984.

- Ottaway, David B. The King’s Messenger: Prince Bandar bin Sultan and America’s Tangled Relationship with Saudi Arabia. New York: Walker & Co., 2008.

- Peterson, J. E. Historical Dictionary of Saudi Arabia. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2003.

- Phythian, Mark. The Politics of British Arms Sales since 1964. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000.

- Riedel, Bruce. Kings and Presidents: Saudi Arabia and the United States since FDR. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2018.

- Safran, Nadav. Saudi Arabia: The Ceaseless Quest for Security. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Ulrichsen, Kristian Coates. The Politics of Vision 2030: Saudi Arabia’s Transformation and the Gulf’s Future. London: Hurst, 2021.

- United Nations Human Rights Council. “Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions: Investigation into the Unlawful Death of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi.” Geneva: UNHRC, 2019.

- Vassiliev, Alexei. The History of Saudi Arabia. London: Saqi Books, 2013.

- Vitalis, Robert. America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.02.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.