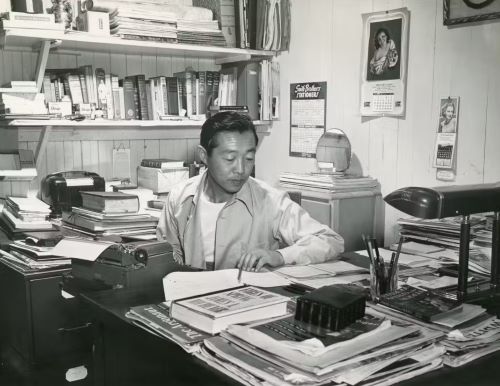

Mori wanted to be a “serious writer” – which, to him, meant getting published.

By Dr. Alessandro Meregaglia

Assistant Professor and Archivist

Boise State University

Introduction

Eighty years ago, on Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which led to about 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in the western United States being moved into internment camps.

At the time, Toshio Mori, a U.S. citizen with Japanese parents, was an aspiring writer who had a contract to publish a collection of his short stories in 1942. As a result of the executive order, however, he was sent to one of the camps, and the publisher delayed the book’s release.

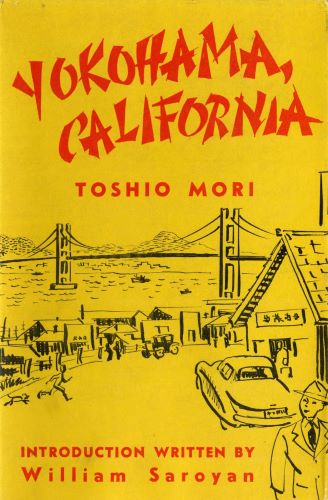

As an archivist and scholar studying publishing in the western United States, I’ve found unpublished and unreported archives that tell the story of Mori’s difficulty getting his book, “Yokohama, California,” published in a country roiled by prejudice against Asian Americans.

Perseverance Pays Off

Mori was born in Oakland, California, in 1910, the son of Japanese immigrants. As he recounted in an interview, Mori wanted to be a “serious writer” – which, to him, meant getting published. He took his neighborhood as his subject and wrote about his majority Japanese community.

Mori turned Oakland into the fictionalized town of “Yokohama” and described the life of the “issei,” or first generation, and their children, the second generation, known as “nisei.”

But Mori had little time to write. He worked full time at his family’s garden nursery, with workdays often stretching to 16 hours. Starting when he was 22 years old, Mori adhered to a disciplined daily schedule in which he would work all day, return home and write from 10 p.m. until 2 a.m.

After receiving dozens of rejection letters – “enough to paper a room,” he quipped – Mori finally had his first story, “The Brothers,” published at age 28 in The Coast magazine.

Mori found a champion for his writing in author William Saroyan, winner of a Pulitzer Prize and an Academy Award. Saroyan read “The Brothers,” liked it, and began encouraging and promoting Mori as a writer, even helping him find a publisher for his short stories.

After being rejected by several New York book publishers, Mori submitted his collection of stories to The Caxton Printers, a small publishing company in Idaho. In his submission letter, Mori made the case for his book:

“I believe that the time has come for someone in our little world to be articulate. … In our present national crisis I believe that the American public would be interested to look into the lives of Japanese Americans living in their communities.”

Caxton accepted the manuscript for publication. James H. Gipson, Caxton’s founder, liked Mori’s collection of stories and recognized their uniqueness.

“It is what you would call a good book,” Gipson wrote in an internal memo, “and it is rather important as it is the first writing dealing with Americans born of Japanese parents, and tells in simple, understandable, and unvarnished language, the problems of the Japanese.”

Saroyan, who was famous at the time, wrote an introduction for the book, in which he called Mori “one of the most important new writers in the country.” On Dec. 2, 1941, Caxton Printers set a tentative publication date for the following autumn.

Five days later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. The U.S. declared war on Japan on Dec. 8.

A Dream Deferred

Even after the attack, Gipson proposed moving ahead with publication as scheduled.

However, just a couple of months later, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which led to Mori and his family being forced from their home in San Leandro, California. First, they were sent to Tanforan Racetrack, a temporary assembly center. They were then interned at Topaz War Relocation Center in the Utah desert, where they remained for three years.

In May 1942, after Mori had been removed from California, Gipson decided to indefinitely delay publication of “Yokohama, California.” Gipson was counting on strong sales to Japanese Americans. But, he reasoned in an internal memo in May 1942, “[the Japanese] are now gathered in concentration camps, however, and it is doubtful that they’ll have any money with which to buy books.”

Another member of Caxton’s editorial staff noted in reply to Gipson that “people are blindly averse” to Japanese Americans. “It may be that there is so much bitterness that it would not sell. One of the most shocking manifestations up to date is the immense growth in racial and religious prejudices.”

More broadly, Gipson explained in a letter to Mori that selling books was a difficult prospect during wartime: “I’m of the opinion that it would be far wiser, for you and for us, if we’d set the date of publication for your book forward to some time in the future. … To bring it out now will mean failure for it in every way.”

Saroyan protested the postponement strongly and urged Gipson to forge ahead with the book’s publication: “Now, more than ever, ‘Yokohama, California,’ should be published.” Mori, too, requested the book appear as scheduled, but ultimately accepted Caxton’s decision.

In a separate letter to Mori, Saroyan implored him to keep writing: “You must write a story or two, or eventually a whole short novel about you and your friends, and people, at Tanforan. That is going to be something people are going to want to read. … In short, keep busy; there is more than ever an urgency for you to write.”

At Topaz, Mori served as the camp historian, working to document major and minor events. Despite the restrictive conditions, Mori did continue writing. He reported to Saroyan that he had “enough material to keep me busy for a long time.” Mori completed a draft of a novel about the internment experience, and several of his new short stories appeared in “Trek,” the Topaz literary magazine.

After the war ended, Mori returned to California and worked in the nursery full-time. He married and had a son.

A Flash of Recognition

The manuscript for “Yokohama, California” lay dormant for the duration of the war. Then, in 1946, Caxton’s editors revived the manuscript and resumed correspondence with Mori. The writer contributed two new stories to the collection, both about the Japanese American experience after American entry into the war.

“Yokohama, California” was finally released in March 1949, and Mori became the first Japanese American to publish a book of fiction. Saroyan’s introduction still appeared at the beginning of the book, with a brief addendum in which Saroyan noted that the book had been “postponed” because of the war, simplifying the complicated history of the preceding years.

Despite receiving favorable reviews in the national press – Mori was variously described as “a natural-born writer,” a “fresh voice” and “spontaneous” – the book did not sell well, and the majority of the copies were eventually discarded. As poet Lawson Fusao Inada put it in a later introduction to Mori’s work, the story collection “slid into oblivion.”

The Birth of a Movement

For the next two decades, Mori continued to write but struggled to find publishers and an audience for his fiction. It wasn’t until the next generation of Japanese Americans – the “sansei,” or third generation – that Mori finally began receiving recognition for his pioneering work of Japanese American literature.

The nascent Japanese American literary movement coalesced in 1975 with the first meeting of the Nisei Writers’ Symposium in San Francisco. Mori was one of four authors featured at the conference. The following year, the University of Washington hosted a similar conference, where Mori was again an honored guest and read from his work.

These groups’ efforts brought renewed attention both to Mori and to other nisei Japanese American writers. With this new spotlight, Mori published a novel, “Woman from Hiroshima,” in 1978, and a second collection of short stories, “The Chauvinist and Other Stories,” in 1979. He died the next year at the age of 70.

Mori wasn’t the only Japanese American author who received recognition years after his work first appeared. The publishing saga of John Okada’s “No-No Boy” is fraught with sadness. Okada died before his novel received critical acclaim; his widow couldn’t find an archive that wanted his papers, so she destroyed them.

“Yokohama, California” remained out of print for 35 years before the University of Washington Press added it to their “Classics of Asian American Literature” and reprinted it in 1985. The book continues to be available through the publisher. Another edition was released in 2015.

Decades after he was held at Topaz, Mori visited the site of another internment camp and noted that “many people in my generation are reluctant to discuss those events, because they are ashamed they were suspected of disloyalty.”

He pushed back against this impulse, however: “I feel a reminder is important to prevent this from happening again.”

Originally published by The Conversation, 02.15.2022, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.