The new terms may expose universities to significant legal risk.

By Sarah Talpos

Science Journalist & Editor

Earlier this year, a biomedical researcher at the University of Michigan received an update from the National Institutes of Health. The federal agency, which funds a large swath of the country’s medical science, had given the greenlight to begin releasing funding for the upcoming year on the researcher’s multi-year grant.

Not long after, the researcher learned that the university had placed the grant on hold. The school’s lawyers, it turned out, were wrestling with a difficult question: whether to accept new terms in the Notice of Award, a legal document that outlines the grant’s terms and conditions.

Other researchers at the university were having the same experience. Indeed, Undark’s reporting suggests that the University of Michigan — among the top three university recipients of NIH funding in 2024, with more than $750 million in grants — had quietly frozen some, perhaps all, of its incoming NIH funding dating back to at least the second half of April.

The university’s director of public affairs, Kay Jarvis, declined to comment for this article or answer a list of questions from Undark, instead pointing to the institution’s research website.

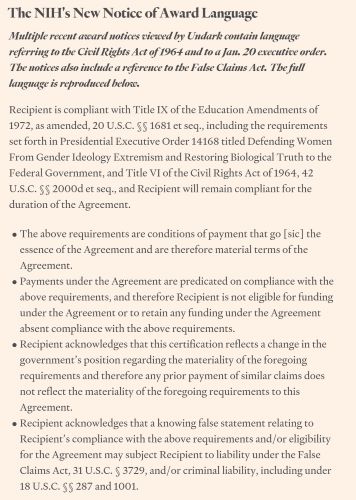

In conversations with Michigan scientists, and in internal communications obtained by Undark, administrators explained the reason for the delays: University officials were concerned about new language in NIH grant notices. That language said that universities will be subject to liability under a Civil War-era statute called the False Claims Act if they fail to abide by civil rights laws and a Jan. 20 executive order related to gender.

For the most part, public attention to NIH funding has focused on what the new Trump administration is doing on its end, including freezing and terminating grants at elite institutions for alleged Title VI and IX violations, and slashing funding for newly disfavored areas of research. The events in Ann Arbor show how universities themselves are struggling to cope with a wave of recent directives from the federal government.

The new terms may expose universities to significant legal risk, according to several experts. “The Trump administration is using the False Claims Act as a massive threat to the bottom lines of research institutions,” said Samuel Bagenstos, a law professor at the University of Michigan, who served as general counsel for the Department of Health and Human Services during the Biden administration. (Bagenstos said he has not advised the university’s lawyers on this issue.) That law entitles the government to collect up to three times the financial damage. “So potentially you could imagine the Trump administration seeking all the federal funds times three that an institution has received if they find a violation of the False Claims Act.”

Such an action, Bagenstos and another legal expert said, would be unlikely to hold up in court. But the possibility, he said, is enough to cause concern for risk-averse institutions.

The grant pauses unsettled the affected researchers. One of them noted that the university had put a hold on a grant that supported a large chunk of their research program. “I don’t have a lot of money left,” they said.

The researcher worried that if funds weren’t released soon, personnel would have to be fired and medical research halted. “There’s a feeling in the air that somebody’s out to get scientists,” said the researcher, reflecting on the impact of all the changes at the federal level. “And it could be your turn tomorrow for no clear reason.” (The researcher, like other Michigan scientists interviewed for this story, spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.)

Bagenstos said some other universities had also halted funding — a claim Undark was unable to confirm. At Michigan, at least, money is now flowing: On Wednesday, June 11, just hours after Undark sent a list of questions to the university’s public affairs office, some researchers began receiving emails saying their funding would be released. And research administrators received a message stating that the university would begin releasing the more than 270 awards that it had placed on hold.

The federal government distributes tens of billions of dollars each year to universities through NIH funding. In the past, the terms of those grants have required universities to comply with civil rights laws. More recently, though, the scope of those expectations has expanded. Multiple recent award notices viewed by Undark now contain language referring to a Jan. 20 executive order that states the administration “will defend women’s rights and protect freedom of conscience by using clear and accurate language and policies that recognize women are biologically female, and men are biologically male.” The notices also contain four bullet points, one of which asks the grant recipient — meaning the researcher’s institution — to acknowledge that “a knowing false statement” regarding compliance is subject to liability under the False Claims Act.

Alongside this change, on April 21, the agency issued a policy requiring universities to certify that they will not participate in discriminatory DEI activities or boycotts of Israel, noting that false statements would be subject to penalties under the False Claims Act. (That measure was rescinded in early June, reinstated, and then rescinded again while the agency awaits further White House guidance.) Additionally, in May, an announcement from the Department of Justice encouraged use of the False Claims Act in civil rights enforcement.

Some experts said that signing onto FCA terms could put universities in a vulnerable position, not because they aren’t following civil rights laws, but because the new grant language is vague and seemingly ripe for abuse.

The False Claims Act says someone who knowingly submits a false claim to the government can be held liable for triple damages. In the case of a major research institution like the University of Michigan, worst-case scenarios could range into the billions of dollars.

It’s not just the dollar amount that may cause schools to act in a risk-averse way, said Bagenstos. The False Claims Act also contains what’s known as a “qui tam” provision, which allows private entities to file a lawsuit on behalf of the United States and then potentially take a piece of the recovery money. “The government does not have the resources to identify and pursue all cases of legitimate fraud” in the country, said Bagenstos, so generally the provision is a useful one. But it can be weaponized when “yoked to a pernicious agenda of trying to suppress speech by institutions of higher learning, or simply to try to intimidate them.”

Avoiding the worst-case scenario might seem straightforward enough: Just follow civil rights laws. But in reality, it’s not entirely clear where a university’s responsibility starts and stops. For example, an institution might officially adopt policies that align with the new executive orders. But if, say, a student group, or a sociology department, steps out of bounds, then the university might be understood to not be in compliance — particularly by a less-than-friendly federal administration.

University attorneys may also balk at the ambiguity and vagueness of terms like “gender ideology” and “DEI,” said Andrew Twinamatsiko, a director of the Center for Health Policy and the Law at the O’Neill Institute at Georgetown Law. Litigation-averse universities may end up rolling back their programming, he said, because they don’t want to run afoul of the government’s overly broad directives.

“I think this is a time that calls for some courage,” said Bagenstos. If every university decides the risks are too great, then the current policies will prevail without challenge, he said, even though some are legally unsound. And the bar for False Claims Act liability is actually quite high, he pointed out: There’s a requirement that the person knowingly made a false statement or deliberately ignored facts. Universities are actually well-positioned to prevail in court, said Bagenstos and other legal experts. The issue is that they don’t want to engage in drawn-out and potentially costly litigation.

One possibility might be for a trade group, such as the Association of American Universities, to mount the legal challenge, said Richard Epstein, a libertarian legal scholar. In his view, the new NIH terms are unconstitutional because such conditions on spending, which he characterized as “unrelated to scientific endeavors,” need to be authorized by Congress.

The NIH did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Some people expressed surprise at the insertion of the False Claims Act language.

Michael Yassa, a professor of neurobiology and behavior at the University of California, Irvine, said that he wasn’t aware of the new terms until Undark contacted him. The NIH-supported researcher and study-section chair started reading from a recent Notice of Award during the interview. “I can’t give you a straight answer on this one,” he said, and after further consideration, added, “Let me run this by a legal team.”

Andrew Miltenberg, an attorney in New York City who’s nationally known for his work on Title IX litigation, was more pointed. “I don’t actually understand why it’s in there,” he said, referring to the new grant language. “I don’t think it belongs in there. I don’t think it’s legal, and I think it’s going to take some lawsuits to have courts interpret the fact that there’s no real place for it.”

Originally published by Undark Magazine, 06.17.2025, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.