Authoritarian leaders have in the past used assassination attempts to burnish a strongman image and Trump is doing the same.

By Dr. Ruth Ben-Ghiat

Professor of History and Italian

New York University

Introduction

What does history tell us about assassination attempts on populist leaders?

The history of strongmen is also the history of their opponents’ efforts to use force to remove them from power. Although authoritarian leaders often present their violence as justified and necessary – saving the country from dangers posed by internal or external enemies is the propaganda standard – their persecutions of so many people and policies that can lead nations into ruin create the conditions for violence to be used against them as well.

Assassination attempts can be the work of lone individuals, organized resistance cells in the country or people living in exile. They can also be the result of operations conducted by intelligence services of hostile countries, as with the multiple failed CIA operations to kill Cuba’s longtime Communist leader Fidel Castro.

“If surviving assassinations were an Olympic event, I would win the gold medal,” Castro once commented.

Many authoritarians become targets of assassins at the start of their time in office – after they have made enemies but before they have developed an infrastructure of secret police and adequate security protocols.

Surviving multiple early attempts on their lives can boost a political leader’s personality cult and claims of invincibility. It can also serve as a justification for any crackdowns or repressive policies.

Then they can last in office a long time. Mussolini, who survived four assassination attempts from 1925 to 1926, went on to hold power for 17 years.

Other leaders are targeted throughout their rule. Adolf Hitler survived dozens of attempts on his life by individuals and groups. The Führer’s dysfunctional leadership, especially in military matters, led high-ranking German military officials to plot against him starting in the late 1930s, culminating in the July 20, 1944, explosion at his headquarters in East Prussia that left him lightly injured.

And when dictators have been in power long enough to have a veil of secrecy around everything – as Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi, who was in office for 42 years, managed to do – it can be difficult to track all of the attacks on their person from military and civilian resisters. He, too, survived dozens of attempts, at least 10 between 1980 and 1985, some of which took the form of attempted coups from within the Libyan military.

What impact did surviving have on their popularity?

It can be difficult to gauge popularity in a dictatorship, where outward behaviors of applauding the leader in public do not always correspond to inner feelings – people know the cost of expressing any support for the leader meeting an untimely end.

Yet assassination attempts can cause a wave of sympathy for leaders that can boost their personality cults as well.

And with each failed attempt, the personality cult themes about the leader’s macho toughness, resilience and invincibility gain credence among his followers. This was certainly the case with Castro and Mussolini, and it has been the case so far with former President Donald Trump.

How did those men use assassination attempts to their advantage?

From Mussolini and Hitler onward, strongmen have posed as victims of internal and external enemies, as well as protectors of the nation – as the only individuals who could save the people and lead them to greatness.

Ideologies of victimization – with the leader depicting himself as the symbol of an entire persecuted people – are part of the tool kit of virtually every sitting authoritarian leader. Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić is just one of many who depict themselves as under relentless attack by their enemies.

Opponents can come to believe that by eliminating an authoritarian leader, it will put an end to the regime. But failed assassination attempts give these victimhood narratives a concrete reference point and credibility.

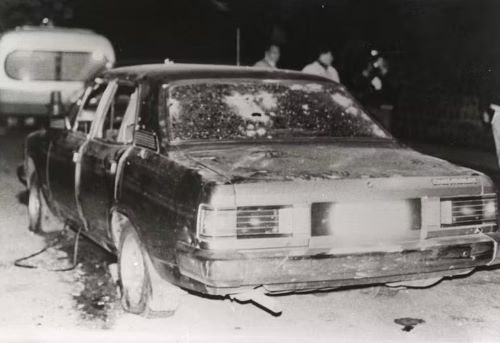

That is why leaders sometimes advertise their harrowing experiences. After a bullet grazed his nose in April 1926, Mussolini posed for a photograph with a big white bandage to show his devoted supporters. And Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet was photographed with a bandaged hand next to his bullet-ridden Mercedes after a 1986 ambush by Chilean Communist operatives.

Since in authoritarian states attacking the leader is seen as attacking the nation itself, even peaceful critics may be labeled as enemies of the entire nation or even as terrorists in subsequent crackdowns. This happened in Russia under Vladimir Putin and Turkey under Recep Tayyip Erdogan – an actual attempt to kill the leader can justify the states of emergency that follow.

What other consequences have there been?

The aftermath of the 1986 attempt on Pinochet’s life suggests that failed assassination attempts do not always cause a surge in popularity if the leader is already on the downward arc of his reputation and the majority of the population wants him to leave office. They can also cause resisters to reevaluate their tactics.

By 1986, when the Communist Party’s Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front ambushed Pinochet on a country road as he returned from his weekend house in El Melocotón, outside of Santiago, Chileans were exhausted from the violence of the regime, and a nonviolent mass protest movement had been building for a few years.

The assassination attempt, during which light antitank rockets, grenades, M16 rifles and more were used, killed and wounded several members of Pinochet’s security detail but left Pinochet, who was traveling in a brand-new armored Mercedes with bulletproof tires, lightly wounded.

“I am no saint or Mohammed. If they give me a slap in the face, I strike back with two,” Pinochet told journalists the next day. Soon, corpses of leftists bearing signs of government torture appeared around Santiago. By 1986, the junta’s brutality had lost its support, but the Communists’ armed response to regime violence seemed misguided to many. Many Christian Democrats and conservatives agreed with the Socialists’ denunciation of a Communist strategy that “only means more pain and death for the people of Chile.”

The assassination attempt drove a larger wedge between the Communists committed to armed revolution and other opposition forces, and it brought nonviolent resisting parties closer together, hastening the end of the regime.

Are we seeing some of these trends already playing out with Trump?

The effects of the assassination attempt on Trump are so far in line with authoritarian history. Chief among its aftereffects is a boost to Trump’s victimhood persona. He had always told his devoted followers that the “enemies” were not going after him, but rather going after them, and he was “just standing in the way.”

The July 13, 2024, assassination attempt will seem to validate that claim in the eyes of Trump’s faithful, especially since a person attending the rally was killed by the shooter and others were injured.

The attack has also brought Trump even more loyalty from followers bonded to him. At the RNC, many wore ear bandages as signs of support. Trump’s wounds are their wounds too – to them, he embodies the nation, expresses their sufferings and risks his safety on their behalf.

Trump’s campaign has always had vengeance and retribution for those who persecute him, in his telling, as a central theme. He and his allies have talked about investigating those who have tried to hold him accountable. Meanwhile, the Project 2025 plan for governance, put together by a think tank with ties to Trump, includes mass firings of nonloyalists, an expansion of executive branch powers and other pillars of authoritarian governance.

The assassination attempt on Trump may be used as justification for these measures, just as other attacks have been used by other authoritarians in history.

Originally published by The Conversation, 07.25.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.