Exploring rhetorical and linguistic qualities, including matters such as style, narrative, and genre.

By Dr. Emma Claussen

British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow

Affiliated Lecturer

University of Cambridge

By Dr. Luca Zenobi

Research Fellow, Trinity College

Affiliated Lecturer, Faculty of History

University of Cambridge

Introduction

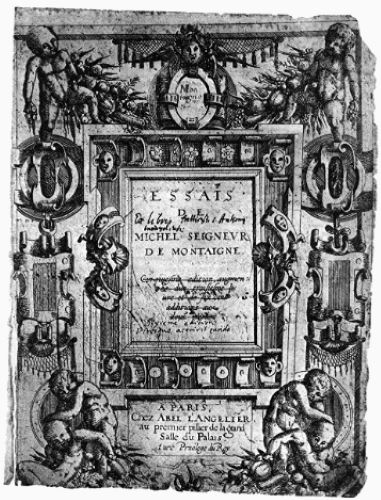

Truth and falsehood are alike in face, similar in bearing, taste, and movement; we look upon them with the same eye. I find not only that we are lax in defending ourselves against deception, but that we seek and hasten to run ourselves through on it.

Montaigne, Essais.1

Over the last few years, the phrase ‘fake news’ has become ubiquitous. Scholars and commentators alike have raised alarm over the spread of disinformation. Worries about the corrosive effects of social media feature regularly in articles and opinion pieces, often in explicit contrast to older means of communication, such as newspapers and printed books. Social scientists now explicitly refer to the onset of a new cultural and technological reality, one in which facts and opinions are constantly muddled, data is cherry-picked to suit individual claims, outright lies are the norm rather than the exception, and false narratives are habitually presented as actual truths.2 A slew of non-fiction books has gone as far as to announce the ‘death of truth’ and the dawn of an era in which the hegemony of science has broken down, the authority of experts is called into question, and the distinction between facts and fiction no longer matters.3 In 2016, shortly after Donald Trump’s election to the US presidency and the success of the Leave campaign in the Brexit referendum, the Oxford Dictionaries chose ‘post-truth’ as their Word of the Year, signalling the irreversible unfolding of that very era.4

Yet despite what this bleak picture may suggest, fake news is nothing new. Today’s versions may be culturally and technologically specific, but hoaxes, lies and fabrications have been around for as long as people have exchanged information in any shape or form, told stories, and generally talked and written to each other. Some scholars have been quick to challenge the idea that what we have left behind was an era of truth and reason that began with the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution. They have also questioned the notion that democracy was ever devoid of tensions between the truths believed by the masses, and those envisioned by politicians, experts and news media.5 Indeed, one would struggle to find a scholar of any historical discipline who could not think of any text or moment from our past marked by false information or fictionalized retellings. The propaganda effort launched by Octavian against Mark Antony over two thousand years ago is often hailed as the first example of a disinformation war, one fought with fake documents, gossip, and soon distorted accounts of the events, all broadcast to the Roman public using the main media of the time: poetry, iconography and even coins.6

The aim of this Supplement is to study another major juncture marked by new technologies, genres and regimes of truth: the early modern period. Historians of information have already drawn parallels between the internet age and the first few centuries of print culture.7 The possibility of applying terms such as ‘fake news’ and ‘disinformation’ to early modernity has also been explored.8 We hold that such concepts are useful tools for thinking about — and beyond — truth in early modern Europe, and that they connect our work with that of scholars working on different periods and regions of the world. In our title, we refer to disinformation (and indeed fiction) as being ‘beyond truth’ not in the sense that truth does not matter or is always unreachable but rather to mark our interest both in the experience of discerning truths and in texts that are typically placed outside the boundaries of the truthful. ‘Fake news’ and ‘disinformation’ are terms indicating crises of communication centred on veracity and trustworthiness. In this volume, we analyze the cultural and creative aspects of such crises, alongside their significance for readers and writers. ‘Disinformation’ is also a term associated with the internet age,9 and this volume is similarly concerned with the impact of new ways of communicating on society at large. Many of our chapters connect their analysis with issues we face today, but each of them offers a case study focused on a particular time and place.

Our shared premise is that a key aspect of disinformation is how exactly it is written into texts and disseminated among readers. These processes are similar to those of other fictional writings, including literary fictions, which saw an explosion in both output and reach in early modernity equivalent to that of texts that can be categorized as disinformation. We therefore offer, in this Supplement, an integrated account of fiction and disinformation in the early modern period. Specifically, we work from the consideration that fiction and disinformation share some important commonalities: both are recounted and both are fabricated. The very word ‘fiction’, derived from the Latin fingere, itself contains this commonality: as described by Natalie Zemon Davis, it can refer to the ‘literary quality’ of certain texts, but it can also allude to the feigned nature of some accounts.10 In short, fictions can be lies as well as stories. However, all lies are told, like any stories; and all stories, including those making verifiable truth claims, are also works of imagination. This last remark may appear to pit all kinds of fictions (including disinformation) against actual facts. But as Lennard Davis writes, ‘when “fact” and “fiction” are used, they are not defining two distinct and unimpeachable categories. They are more properly extremes of a continuum’.11 Much like the Latin fingere, the French word faict already expressed this complexity in the early seventeenth century. In Cotgrave’s dictionary, its meaning ranged from ‘done, acted, made’ to ‘wrought, forged, composed’.12

This volume highlights texts, episodes and circumstances that exemplify such finely wrought connections not only between fact and fiction but also between fiction and disinformation. Driven by the belief that matters of textuality, evidence and truthfulness do not belong to any one discipline, we set out to explore these connections using a combination of literary and historical approaches. Our method involves, as a starting point, analysis of the rhetorical qualities of our sources, understood as technical elements used to construct a narrative — to turn facts (and sometimes falsehoods) into stories, information into knowledge, ideas into invitations to believe. This means examining the aesthetic as well as practical concerns that inform textual production, while also reflecting on the limits of representation, on the referential capacities of both oral and written idioms, and on their capacity for distortion and manipulation. Although, in some cases, information is unintentionally or accidentally warped, the titular emphasis on disinformation also reflects the volume’s interest in authorial intention, and in the agency involved in the dissemination as well as reception of stories.13 In brief, we are attentive to the ways in which critical and/or uncritical readers, and writers by either accident or intention, identify and, to an extent, define fiction and disinformation. This makes the volume as a whole a contribution to the cultural history of reading and writing, one which intersects with the history of concepts such as trust, authority and credibility.

Within this, reading and writing must be contextualized: every chapter in this Supplement examines these practices also as social phenomena. This means considering fiction and disinformation in relation to the individuals who crafted and facilitated them, the groups and institutions which enabled or hindered their fabrication, as well as their impact on audiences and society at large. The premise is that studying how fiction and disinformation were recounted can help us better understand not only what the past was like but also how people re-imagined it, thus bringing about change in early modern society: changes in regimes and power balances; in customs and social practices; and in cultural attitudes and literary tastes. Fundamentally, the challenge is to think about the world of texts in the context of the world beyond them — to work out what happens in and around our sources, but also because of them. This approach is in the spirit of much literary theory, emphasizing, with Mieke Bal, that ‘imagination is part of reality, even if the worlds it produces may not exist’.14 But it is also an attempt, in the wake of many other social histories (of language, of knowledge, of media, of keywords, of the archive) to contribute to the broader social history of early modern information, media and communication, which in turn overlaps with fields such as the history of memory, identity and politics.15

The rest of this Introduction sets out the historical, scholarly and methodological contexts for the volume. The piece is divided into three sections. The first section places fiction and disinformation in the context of broader shifts taking place in early modernity. It does so by outlining the specificities of this period, as well as the circumstances which ultimately led to the making and circulation of falsehoods and fictional accounts on an unprecedented scale. The second section surveys the state of the field in both historiography and literary criticism. It traces the origin and development of multiple scholarly avenues connected to these themes, highlighting points of contact as well as divergence between the two disciplines. The third and final section outlines the approach which informs all the chapters gathered here and assesses their combined answer to the question of how fiction and disinformation worked with and against each other in early modern Europe.

Part I

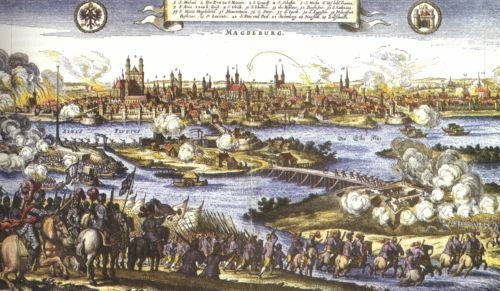

Fiction and disinformation were central to and reflective of many trends and developments of the early modern period. For a start, the world itself was changing; more than that, what people understood the world to be was being questioned. European encounters with people from the rest of the globe revealed evidence that contradicted locally established truths; these inspired creative fictions that sowed further disinformation. In the sixteenth century, as cosmographers challenged long-held assumptions about the earth itself, humanists who sought to syncretize different traditions into a singular truth exposed the precarity of that very concept. Later scientific methods looking for alternative means of discovering truths were partly a reaction against humanism, but these new approaches provoked other conflicts over proof themselves. The early modern period was further marked by epistemological fractures wrought by the Reformation, which challenged the centrality of Rome and, with that, the established systems of knowledge inherited from the Middle Ages. In turn, this fuelled a series of conflicts — the French and English Civil Wars, the Thirty Years’ War — which were fought in part over these competing truths, and inspired others in the form of news reports and propaganda. In the later seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries, political and colonial conflicts followed comparable patterns. The accompanying news reports also influenced the rise of the novel, which had become a pre-eminent fictional genre by the end of the period. Overall, although fiction and disinformation are features of every historical era, the early modern period saw distinct crises of truth not only at peaks of violence and political turbulence but embedded in culture. And, as we shall see, the period was marked by concerted attempts to resolve these crises which leave their mark on scholarship to this day.

These changes depended on a series of related developments that occurred — widely, if variably — throughout Europe. Briefly summarized, these are: expansion in the tools available for communication (paper, print and post), expansion in the forms of communication (among others, broadsheets, pamphlets, gazettes and newspapers — not to mention diplomatic and scientific correspondence), and expansion in the number of people taking part in the new systems of communication and knowledge formation.16,17,18,19 These developments were unevenly distributed across space and time, but there are broad trends across the three or so centuries that make up early modernity. To take the example of literacy, rates varied depending on location — urban centres had higher rates than rural areas and some countries had much higher rates than others — but the wider trend is clear, as Ann Blair has recently noted: ‘literacy rates rose in western Europe from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century, from estimated averages of 5–15 per cent in 1500 to 50–75 per cent in 1750’, leading to a much wider audience for written texts, and thus for printed fictions and disinformation.20 Overall, similar to the internet and its new platforms today, movable type and cheap paper drastically lowered the barrier to access, and correspondingly increased the fabrication of lies and inaccuracies, the coexistence of diverging accounts and the dissemination of all kinds of fictional writings. Simultaneously, the growth of postal networks, coupled with trends such as the increased literacy rates described above, facilitated the circulation of both deliberate and unintended falsehoods on a whole new scale.

And much like today, there were concerns. For a long time, trusting information had meant trusting the messenger that bore it. In living up to their name as media, printing and the news industry broke that ‘vital link’ between individuals.21 Now people were asked to trust a publication, not a person. More importantly, they were asked to trust one of numerous and often anonymous printed texts circulating at the time, not someone they knew or who worked for them. This only increased as time went on, and especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the number of publications increased exponentially: by the late eighteenth century, the German states had the largest newspaper-reading audience (with a total press run of roughly 300,000 copies a week), and most literate adults could access newspapers in England, France, the Netherlands and northern Italy.22

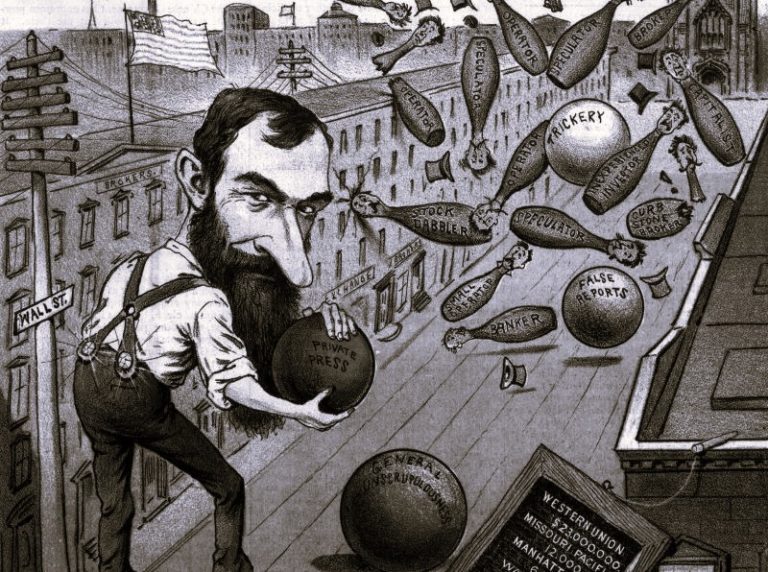

Despite, or perhaps because of, the growing number of outlets, information remained hard to verify. It took time to develop a coherent ethics of journalism. Some have even argued that the principle of objectivity in news reporting, as we understand it now at least, only emerged in the twentieth century.23 In a pioneering essay of more than twenty years ago, Brendan Dooley compiled an impressive array of episodes and circumstances that caused seventeenth-century intellectuals to cast doubt over the news: they worried about partisanship, government interference, stylistic experimentation that detracted from reporting, and the pressure writers were under to entertain their public and ultimately make a living.24 Judging from the treatment of news and news outlets in contemporary poetry, ballads and theatre, at least part of the population shared their anxiety. A recent study of English texts shows people lamenting how overwhelming, unreliable and sometimes totally dishonest information could be.25 Some blamed the bias of writers and editors alike, others mocked their ignorance of the events or simply their sheer ineptitude; others still referenced their drive to make a profit, often through tactics still common nowadays (such as baits, exaggerations and various forms of recycling). What is more, newsprints themselves often publicly denounced each other as purveyors of false accounts, as indeed some still do nowadays.

Historians were involved in similar reckonings. The early modern period saw the appearance of a new kind of historical consciousness, the development of the first new treatises on historical method and a print-driven explosion in the numbers of writers and readers of history.26 But it also saw an equivalent rise in the use and abuse of history, and in the disputes that have always accompanied such practices. Like news writers, historians often denounced one another as enemies of the truth. The confessional historiographies of the Reformation are a well-known example of such exchanges.27 In their attempt to uphold theological verities, Protestants and Catholics alike had no qualms about forging records and distorting the past. The former endeavoured to provide reformed churches with a more established tradition, typically by rewriting the lives of ancient heretics into a long history of their current beliefs. The latter were trying to show that no matter the demonstrable deviations, the Catholic Church had always been true to its God-given mission. Mistrust ensued: the identity of the writer, and especially their religious identity, was often enough to discredit a piece of scholarship or simply prompt the writing of a contrasting — and sometimes partly fictional — account. The same applied to works sponsored by secular rulers: from the historical writings of the Ottoman court to Venice’s municipal histories.28

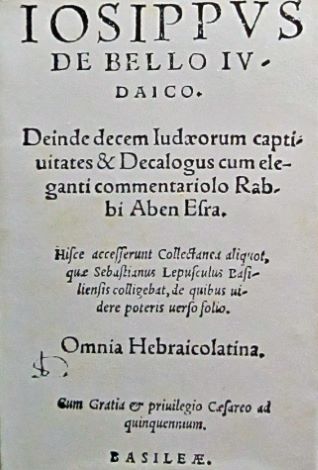

Of course, not all writers set out to twist the truth. Sometimes falsehoods were but a result of the challenges they faced. This was, first of all, a problem of evidence. Combined with technological advances, the expansion of scholarly endeavours uncovered an unprecedented amount of material, including originals as well as commentaries, full texts as well as fragments, and works in other languages as well as translations. And of course, the more information was brought to light, the larger became the scope for discrepancies and errors. New tools were developed to manage this information boom: from scientists’ notes and chancery lists to reference volumes and commonplace books.29 However, the tools of criticism were not always sharp enough to deal with what Nicholas Popper has described as a potential ‘ocean of lies’.30 In addition, there was a problem of familiarity. While drawing on sometimes dubious ancient and medieval knowledge, early modern scholars could be writing about worlds they had never written about before. How to reconcile the pasts of little-known societies, people and continents into that of Europe, Christianity and its monarchies? In the end, new information from faraway lands was woven together with facts and evidence which had long been known in the Mediterranean world. And as new myths and rumours found their place alongside accepted truths, the boundaries between them were blurred and any significant gaps were filled by imagination.31 The same process occurred in cartography, philosophy, poetry and all sorts of official records.32 Together, these materials shaped the world as people knew it at the time, but they also raised significant questions as to the origins and truthfulness of a great deal of knowledge.

As the relationship between fact and fiction became more contested and dynamic, Europe saw an explosion in creative fictions that exploited this. From the late fifteenth century, as Ann Moss showed in her landmark study of ‘Renaissance Truth’, attitudes to fiction itself were becoming ever more complex.33 The ambiguous status of history, which before the nineteenth century was considered a branch of rhetoric, that is to say a ‘literary’ genre, was at the heart of this process.34 The very word ‘history’ was used in the title of both news reports and prose fictions, just as ‘news’ and ‘short story’ are expressed by the same word group (nouvel) in early modern French. The sheer volume of material circulating, and the many conflicting narratives about new worlds and new ideas, further inspired creative imitations, parodies and imaginative reworking of ‘history’, ‘news’ and everything in between, catering to a new and expanding market for recreational literature.35 Isabelle Moreau has referred to an ‘astonishing variety of fictional experiments’ being conducted in this period.36 The novel emerged in this context. Cervantes’s Don Quixote (1605–15) is sometimes cited as the first of the genre, although medieval and sixteenth-century forerunners have also been mooted. In general, the novel is thought to have become a recognizable literary form, and then a major one, across Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.37

Still, the story is larger than that of a single genre. Especially in the earlier part of the period, fiction was primarily associated with poetry and poetic techniques — understood both as a kind of ‘counterfeiting’, as Philip Sidney described poetry, but also as a means of revealing truths.38 History (both ancient and recent) was a crucial source of inspiration for theatre and poetry, and a spur to ethical reflection. In such works, the truth of history was often understood more in terms of moral exemplarity than factual accuracy.39 However, some fiction was also concerned with factual or biographical truths. Consider the vogue for Romans à clef (loosely fictional narratives, often partly autobiographical and concerning recent real events) written by women such as Madeleine de Scudéry, Madame de La Fayette and Madame de Villedieu in seventeenth-century France. Their popularity and influential role in shaping the European fictional canon indicates that writers and their audiences were aware of, and compelled by, the subtle distinctions between real life and fiction.40 Eighteenth-century writers built on this to make arguably bolder, and often satirical, moves exploiting the boundaries between life and art: readers were preoccupied with ‘deception and shamming’ in fictions, or with finding the ‘true’ inspiration of fictional texts. Samuel Richardson’s bestselling Pamela (1740), which the author claimed was based on a true story, provoked such a reaction, as well as a satirical rewrite by Henry Fielding, under the title Shamela.41 The modern sense of ‘fiction’, previously indicating more a technique or quality than a cultural category, came from such experiments in the representation (or deliberate misrepresentation) of experience.

Part II

These developments have long been at the forefront of the scholarly agenda and certainly contributed to the emergence of history as a distinct discipline, such that attention to fiction and disinformation has always been an integral part of the work of the historian. Ancient writers, themselves purveyors of all sorts of myths, were obsessed with the idea of ‘telling nothing but the truth’.42 Fiction (near synonymous with ‘poetry’ before the early modern period) was also long juxtaposed against historical truth. Cicero wrote that poetry might be appraised according to the pleasure it gives, but in history, truth is ‘the standard by which everything is judged’.43 Quintilian made a similar point, setting the narrative of history (intended as the exposition of facts) aside from those of comedy and tragedy.44 Other writers spent much time denouncing the work of their predecessors as unreliable or outright mendacious. Plutarch’s memorable invective against Herodotus comes to mind: cited by many as the father of history, he was also known as the father of many lies.45 Even works of mythography were guided by the principle of setting truths aside from falsehoods. A fragment of the Genealogies by Hecataeus of Mileto opens with a stark methodological statement: ‘I write what seems to me to be truth; for the Greeks have many stories that, as it appears to me, are absurd’.46

In the sixteenth century, when the first new theories of history were published by figures such as Paolo Sarpi and Jean Bodin, they revealed a striking faith in the possibility of discerning the ‘truth of the facts’ (Sarpi) and then presenting it as a ‘true narration of things’ (Bodin).47 This view of history was only sharpened by the sceptical and methodological crises of the seventeenth century; when Pierre Bayle composed his Historical and Critical Dictionary at the turn of the eighteenth century, he claimed that scholars had never been more equipped for the correction of factual error, ‘never more devoted’ to ‘this sort of illumination’.48 It is worth noting that in making such claims, these writers contributed to the mythologization of earlier (and especially medieval) periods as uninterested in truth-telling, although medievalists today have countered that kind of historiographical disinformation. Jamie Kreiner, for example, points out that ‘hagiography was predicated on a model of truth that is different from ours’ — a model from which, we might add by extension, early modern historians sought to differentiate themselves.49 By the time Leopold von Ranke arrived on the scene in the nineteenth century, early modern historical methods aimed at the extraction of a certain kind of truth were ready to be translated into a code of practice for the modern historian. History, wrote Ranke in a much-cited passage, should be ‘the naked truth without any ornaments’ and contain ‘no fiction, not even in details, and no fantasy’.50

Today the idea that one can entirely sort fact from fiction is itself something of a fantasy, even if ‘that noble dream’ of objectivity, as Peter Novick framed it, has not been entirely lost.51 Decades of constructivist and relativist thinking have convinced most scholars that there is no such thing as a singular truth to be extracted from texts.52 Instead, truth is constituted as the historian interprets the facts or even, with Hayden White, made in the ‘fiction of narrative’.53 In brief, history is what historians make of it. It is an ‘account’, to use Paul Veyne’s terminology, based primarily on the way historians arrange their evidence.54 Concomitantly, the status (and style) of archival texts has also been problematized amid growing attention to what gets left out, both accidentally and deliberately.55 How can history account for those whose lives are poorly documented or leave little material trace? In response to absences and silences in the historical record, Saidiya Hartman has suggested that the answer is something akin to a ‘subjunctive’ history, one written with and against the ‘limits of the archive’ — a historical method that she calls ‘critical fabulation’.56 Since history-writing is understood to be shaped by our sensibilities and preconceptions as much as by the sources at our disposal, what we are left with resembles less the truth of history and more something like the historian’s truth.57 Of course, this is not exclusively a modern — or indeed postmodern — proposition. Truth-making was already central to Vico’s theory of knowledge, for example.58 What is more, scholars born into a positivist world had readily begun to dismantle it: Lucien Febvre famously noted that ‘every age mentally fabricates its representation of the past’.59 Yet arguably, this remains the dominant scholarly discourse today. We say that something is represented, imagined or indeed fabricated at least as often our predecessors used to say that it had really happened.

Against this backdrop came a new appreciation for sources which do not tell us what really happened and might, in fact, set out to do just the opposite. Such material might reveal what changes people sought to bring to the world, whether by influencing public opinion, tarnishing reputations or persuading their peers of the righteousness of their cause. But it might also open a window into the beliefs and disbeliefs of their audiences — into how groups and individuals understood the world to be. These developments resulted from the tendencies described above, coupled with the broader linguistic turn in the humanities, but they were also the product of continued interdisciplinary work. Later generations of the Annales School, with their interest in mentalities and then cultural practices, are the most obvious example,60 but we could also point to the influence of anthropology on new cultural history and especially on classic microhistory.61 To scholars inspired by these developments, the tales of sixteenth-century imposter, Arnaud du Tilh, were just as relevant as the suit brought against him by the real Martin Guerre, whose identity he stole.62

Still, this does not always mean that ‘what really happened’ — that is, the idea of historical reality as distinct from fiction or fantasy — is not considered important, even in studies that take seriously the linguistic turn and the inherent fictionality of documentation.63 A good example comes from Carlo Ginzburg’s methodological exploration Threads and Traces. In an essay discussing the persecution of Jews in Europe, he considers a case in Vitry-le-François, France, in 1321 that bears resemblance to an episode in Josephus’s The Jewish War set in 67 AD. He asks what historical knowledge can be gleaned from the scant documentation of these events that are narrated in strikingly similar ways, and that had only one or two survivors to state or corroborate the ‘facts’.64 This leads into a discussion of the work of White, Benedetto Croce and others, and ultimately to his conclusion that, despite any document’s ‘highly problematic relationship’ with reality, ‘reality (“the thing itself”) exists’.65 As Ginzburg put it in another of his methodological reflections, the dynamic relation between truth and fiction is less about blurred boundaries between the two and more about the ‘reciprocal, hybrid borrowings’ that a historian will observe: an interwoven thread to ‘untangle’.66

Today, studies of the fake, the false and the fictional remain central in early modern studies, both in terms of texts that disseminate false information through accident or error, and also — as is often the case in this Supplement’s articles — in terms of sources that intentionally distort the truth. The study of forgeries, for example, has expanded from a technical inquiry into the philological qualities of counterfeits to a wide-ranging investigation into the people who made them as well as those who exposed them, and into their motives as much as their methods. Some of these studies also look beyond the boundaries of early modernity; for instance, Margaret Russet’s study of authenticity in the era of Romanticism bridges the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, reminding us of the somewhat arbitrary nature of centuries and eras as historical markers.67 More broadly, looking at forgeries has given historians and literary scholars alike a great deal of insight into the contingent meaning of notions such as originality, representation and identity.68 The same notions form the heart of studies of deceit and dissimulation in early modernity.69 These have recounted the deeds of impostors and liars, but they have also explored how truth was performed and plagiarized, and either recognized or questioned by contemporaries.70 The question of belief and disbelief is also central to much research into the many fantasies (or indeed fictions) that people lived and died by. Witches and demons were no more real than fairies and ghosts, but their representation in various kinds of literature, from folk tales to Macbeth, has told us much about the reality of people’s attitudes and preoccupations.71

Just as some scholars have focused on the blurring and exploitation of the boundaries between fact and fiction in the early modern period, others have investigated how these boundaries were identified and sharpened. Historians of science have long retraced the development of standards for assessing degrees of certainty and probability, the value of testimony and observation and the merit of truth claims. Scientific standards of truth began to be differentiated from other kinds, partly as a result of the environment in which each developed, and science was also influential on other areas of culture.72 This could produce lively debates, such as those between philosopher, Thomas Hobbes, and scientist, Robert Boyle, in the seventeenth century, as the influential study by Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer has shown: ‘Leviathan’s truth and the truth of the air-pump are products of different forms of social life’.73 And yet, as Shapin and Schaffer make clear in their conclusion, both kinds of truth belong to political history, and scientific truths are themselves shaped by politics.

Scholars have shown historians engaged in similar practices. Like their ancient (and modern) counterparts, early modern historians reflected on the tension between fact and fiction — between science and rhetoric.74 Furthermore, scholars have shown how history-writing was progressively differentiated from other kinds of writing, and ultimately transformed into the discipline we know today. Other studies have focused on the techniques developed by early modern historians to assess the truthfulness of information: from philology to diplomatics, and from textual criticism to empiricism.75 Others still have traced how hearsay and received narratives began to be excluded in favour of what historians saw as truthful and verifiable evidence, leading to the use of footnotes that are a standard of rigour to this day.76

Recent works by scholars of theology and religion further show that, much like the new scientific and historical methods, the techniques of disputation and the practice of polemics could result, not only in the challenging of perceived truths and the establishment of new ones, but could also lead to reflections on the concept of truth itself.77 Indeed, beyond the sphere of scholars and intellectuals, studies have uncovered how people across the social spectrum judged the credibility of what they read or heard. Specialists of travel writing, for instance, have suggested that the growing mistrust with which their texts were met by readers forced authors to include discursive as well as paratextual evidence to validate their accounts, while also noting that attempts to export (or escape) religious or moral ‘truths’ were a motivation for travel in the first place.78 Others have demonstrated that early modern people developed a repertoire of strategies to navigate fact and fiction in printed news: from what we now know as cross-referencing to a constant search for confirmation among trusted individuals, and from critical reading practices to a generalized adoption of those same sceptical attitudes already present in much scholarship of the time.79

More broadly, fiction and disinformation have been studied as part of a decades-long investigation into early modern language, media and communication. The aims and focus of this work vary, but two questions are raised by most: how did fiction and disinformation get around? And what effects did their circulation have on individuals and the wider public sphere? Answers to these questions are equally varied, but common threads can be found. For a start, historians and literary scholars alike have explored many arenas in which fiction and disinformation were a matter of both text and speech. Robert Darnton’s Poetry and the Police is a key example, one following a series of ‘abominable poems’ as they were copied, recited and set to music in eighteenth-century Paris.80 Others (predominantly literary scholars) have looked at how slander, satire and gossip spread from mouth to mouth, while also examining their perception and representation in contemporary drama, literature and legislation. In doing so, they highlighted the profound impact of idle talk and malicious speech on the making of identities and reputations, thus ultimately shaping the broader norms and stereotypes which underpinned the public sphere. Well-known examples include the gendered characterizations of transgressive and irrational speech, and the fuelling of anti-Semitic myths, starting from the blood libel.81

In itself, the concept of the public sphere has been crucial to the way in which scholars have problematized the place of fiction and disinformation in early modern communication.82 Aside from works such as those recounted above, much scholarship has been devoted to the explosion of cheap print, notably pamphlets and newspapers. Specialists of early modern France, Italy and the Netherlands were among the first to explore these patterns and their consequences, notably by looking at the fabrication of royal as well as party propaganda (France), at the nature of public discourse as it relates to the burgeoning printing industry (Italy), and at the spread of distorted political messages on the occasion of ceremonial entries and other public spectacles (the Netherlands).83 Another strand concerns Germany, where propaganda, including that based on disinformation or fictional accounts, has been shown to have played a crucial role in the spread of the Reformation beyond intellectual elites.84

More recently, historians of England have been equally active in this area, while even more recent works have appeared on Scotland as well.85 Their interest in fiction and disinformation fits into wider investigations of the relationships between governance and opinion — between politics and the public sphere.86 On the one hand, they have emphasized the many channels and opportunities which allowed both literate and semi-literate people to take part in fabricating as much as consuming the news. In turn, this allowed them to engage with the decisions and behaviour of their rulers on a whole new level, thus expressing a new kind of political awareness, one extending well beyond the elites. On the other hand, they have followed closely the increasing state intervention in the burgeoning public sphere, whether through spreading rumours, manipulating information or through censorship.87 Mark Knights, for example, has shown how the development of new forms of political partisanship ‘ensured that everything could be seen two ways’ — and that people were aware of being surrounded by a world of ‘ambiguities, misrepresentations, and fictions’; in this context, as he put it, the literary and the political were ‘fused’.88

Overall, different forms of fiction have been studied as a corollary or even a technique of acquiring and transmitting knowledge, and as a quality in many of the sources relied on by history for its truth claims. Within all this there is a focus on text and textuality that draws on the tools of literary criticism and poetics, beyond the theories about narrative and temporality that have been so influential on conceptualizations of history-writing. Literary scholars have been attentive to how early modern people themselves viewed the relationship between narrative and truth, and their view of the representative potential of art (understood in dialogue with the Aristotelian idea of mimesis).89 Literature has been assessed as a vehicle for social change, for example as a result of the way in which prose fiction afforded women writers in particular opportunities to make truth claims both about the world at large and, discreetly, about their own experience.90 Analysis of the role of style and ‘literarity’ in constructing fiction and disinformation has also been important in early modern literary studies, particularly rhetorical style: within this there has been particular emphasis on the uses of persuasive rhetoric, its deceptive qualities, and its role in cultures of knowledge and belief.91 Victoria Kahn’s most recent work on this topic, which looks at how rhetoric and poetics affected Reformation ideas about belief in God, argues for ‘a uniquely vexed relation between literature and belief in this period’.92 Literary scholars have further been instrumental in historicizing fiction itself, revealing it as a key heuristic tool of the early modern period: that is, as a means of ascertaining or conveying truths about the world. This applies, not only to ‘science fiction’ and philosophical prose, but to the logical reasoning developed by thinkers such as Descartes, who created analogical fictions and fictional characters (such as the ‘Meditator’ in his Meditations) as part of his philosophical inquiries.93 Indeed, in her recent study, Descartes’s Fictions, Emma Gilby has shown the crucial role of literary culture and theories of poetics in early modern methods of truth deduction.94 These studies show that, while fiction is a prominent form of disinformation in this period, fiction, broadly defined, is also a means of challenging untruths and omissions.

Two common traits unite this diverse body of scholarship. The first is timing. The vast majority of the works discussed in this section have been published during the new millennium, with many appearing only in the last few years. In essence, we are only just getting started. Although literary criticism, the history of the book and print culture, the history of science and, broadly, the study of knowledge formation and communication practices have been around for a very long time, early modernists have never been more interested in historicizing questions of truth and falsehood within these fields. More importantly, we have never been more inclined to traverse the boundaries between them, and consider those questions across a range of sources, frameworks and phenomena. This last tendency is also the second trait uniting the works discussed above: their interdisciplinary nature. Among them, one can find historians carrying out close readings of literary works, such as dramas and novels, but also literary scholars exploring how fictions of all sorts (including rumours, myths and fantasies) shaped and were shaped by the world beyond the text. We could go as far as saying that when it comes to these fields the work of historians and literary scholars has never been more closely aligned.

Part III

This Supplement builds on these foundations. It pays homage to the work of historians who regularly analyze fictions in their work, just as it celebrates literary critics who strive to place all kinds of writings in their broader context. But it also hopes to go beyond cross-pollination and produce a joint investigation. In our case, this means exploring fiction and disinformation in tandem or, more accurately, in light of one other.95 All the essays gathered here consider texts, episodes or circumstances in which fiction and disinformation shared a permeable boundary or even overlapped. There is, however, considerable range in source material as well as approach. The breadth of our time span and potential geographical scope meant that we asked our contributors not to think about any one political or cultural phenomenon in which fiction and disinformation were crucial components, but about fiction and disinformation in themselves, and about how they manifested and interacted with each other. In responding to this, each author provides an original contribution to different sub-fields, including the history of ideas and journalism (Dabhoiwala), the history of poetry and the law (Egan), the history of identity and art criticism (Gage), the history of gender and periodical publications (Steinberger), the history of news and literary genres (Butterworth), the history of philosophy and religious polemics (Reiter), the history of diplomacy and historiography (De Caprio and Rossi), the history of Catholicism and travel writing (Teo) and the history of information and public health (Delogu).

The chapters are based on a selection of papers presented at a conference in Oxford in 2018. Like all the original participants, the nine authors contributing to the volume are an equal mixture of historians and literary scholars, and work with both pragmatic texts and works of imagination (including letters, trial records and newspapers, but also novels, travel accounts and other printed materials). Several are early career scholars working on this common field; others have been instrumental in establishing it as a distinct area of research. The period covered extends from the early sixteenth to the mid-to-late eighteenth centuries, with England, France, Italy and Iberia represented. More regions of Europe, and indeed the world, as well the relationship between fiction and disinformation in colonization, were discussed at the Oxford conference; however, the effects of the Covid pandemic prevented some of our colleagues from bringing their papers to completion. Still, their work shaped what follows in many important ways, which is why we are especially pleased to be able to acknowledge it here.

The Supplement is divided into three parts. The first follows journalists, officials and biographers as they strove to establish their own version of the truth and change people’s views of both past and present as a result. The section opens with a chapter by Fara Dabhoiwala. In exploring how free speech first came to be theorized by two London journalists in the early eighteenth century, he demonstrates that its proponents were themselves guilty of omissions and fabrications. As he shows, despite their reputation as staunch truth-tellers, several falsehoods underpinned the first theories aimed at promoting free expression of the truth. Reputation itself is at the core of the second chapter in the Supplement, by Clare Egan. Taking the English provinces as her case study, she demonstrates that private libels could be a vector for disinformation, one with profound consequences for people’s lives and job prospects, but also a unique form of ephemeral fiction, presented through a variety of media. Similarly, Frances Gage traces the ways in which rumour shaped art criticism and especially the fame of individual artists in early modern Italy. She does so by focusing on the ways in which the life and work of Caravaggio were refracted through the partly fictional accounts written by his rivals, which is another way in which fiction and disinformation intersect in this volume.

The second part of the Supplement considers printed works as domains in which not only fiction and disinformation but also ideas and conventions concerning belief, authority and interpretation were in genesis. The first chapter, by Deborah Steinberger, looks at the nexus between fiction and journalistic work. Analyzing the politically as well as socially motivated stories published in a seventeenth-century French periodical, Steinberger demonstrates that this gave rise to a unique combination of storytelling and news reporting. Emily Butterworth’s investigation into the relationship between short stories and news genres in sixteenth-century France, which follows, complements Steinberger’s study of a later period. Marguerite de Navarre’s fictions, studied by Butterworth, offer resources for identifying truths in a context in which readers knew that they could be faced with falsehoods, foregrounding ideas about reading and discernment in the history of both fiction and disinformation. Moving to England and early seventeenth-century London in particular, Barret Reiter examines religious and moral debates in contemporary polemics, showing, like Butterworth, the effect of the Reformation on conceptions of fiction and truth. He argues that identifying Catholic practices as fictions, including specific forms of liturgy as well as idolatry, was central to printed Protestant texts.

The final part of the Supplement explores different ways in which the boundaries between truth and fiction were crossed and sometimes wilfully blurred when reporting special kinds of information. Returning to Italy, Chiara De Caprio and Andrea Salvo Rossi examine the rhetorical devices employed by Machiavelli to support the credibility of his writing. Considering his diplomatic letters alongside some of his historical works, they demonstrate that reporting his own words, as well as those spoken by others, could give way to plenty of opportunities for source manipulation. Issues of credibility are equally central to Emily Teo’s chapter, which looks at the creative use of hyperbole in travel accounts written by Iberian missionaries. She argues that the motive behind exaggerated descriptions of faraway places like China may have been less to lead readers astray, than to impress and persuade them. Fittingly, given that the Supplement came together during a pandemic, the final chapter is concerned with fiction and disinformation in the context of eighteenth-century epidemics and, notably, attempts at disease prevention. Focusing on Italian port cities as epicentres of the transmission both of disease and information, Giulia Delogu traces the role of false narratives in shaping the intellectual discussion around outbreaks and vaccines.

All contributions investigate matters of language, such as style, narrative and genre. Dabhoiwala, for instance, points to the accessible journalistic prose employed in his sources as one of the key factors which enabled the popularity of the first theory of free speech, while also noting the disdain felt by its proponents for the ‘fictitious’ or even ‘lying mode’ used by contemporary politicians. Aside from Dabhoiwala’s, a number of chapters are focused on distinct rhetorical strategies. De Caprio and Rossi identify Machiavelli’s reported speech as an attempted effet de réel: a device used to imbue texts with verisimilitude, even by purposefully bending the truth. Similarly, Egan presents libellous verses as an ingenious blend of facts and disinformation about the targeted individuals. In turn, Teo’s analysis is centred on the inclusion of hyperbolic descriptions, notably as a way to create an impression of grandeur and abundance when writing about foreign lands; Delogu also points to writers’ hyperbole, even when representing the scientific truth of inoculation’s effectiveness, as a means of engaging readers.

In addition to style, narrative is a key concern of several chapters. Delogu, for example, investigates how diverging concerns, including economic interests as well as moral imperatives, shaped public narratives about smallpox and inoculation. In many cases, this concern led our authors to consider more than one level of narration. Most notably, Gage’s chapter is as much a study of fictions about Caravaggio, and of their receptions across the centuries, as it is a study of the rumours spread by Caravaggio himself, and of the ways in which his behaviour cast shade on the reputation of many other people. Furthermore, all authors analyze multiple kinds of text, while also examining the relationships between them and the extent to which they shaped their individual genres. Butterworth’s chapter is exemplary in this respect. Studying French nouvelles alongside the sensational pamphlets known as canards, she demonstrates that the same concerns informed both literary expression and news reporting. More broadly, thinking about intertextuality across the volume also leads to recognizing that fiction is not always the work of one author or network of agents, but that it can be made and remade over time and across multiple source types.

In all, the nine chapters establish the place of distortions and manipulations of language as part of broader processes of knowledge formation — as cultural products that shaped people’s views and experiences of their reality. But they also uncover ways in which such products could transform those realities; they show that, like the actual events that are usually held as their opposites, fiction and disinformation could drive significant changes in early modern society. Many of the chapters consider how people employed or refuted fictions (albeit with different degrees of self-awareness) in the pursuit of goals such as information, power and reputation. Dabhoiwala’s chapter is as much about the idea of free speech and its textual embodiment as it is about the lives and motives of its advocates, not to mention its dramatic later effects on American society. De Caprio and Rossi observe that Machiavelli’s writing and his political machinations were inextricably linked. They show us a writer who was extremely aware of his own political and rhetorical creativity. Teo makes a similar point about European visitors to China. She argues that in compiling fanciful accounts of a distant utopia, these travellers were seeking to further their careers by stressing the benefits of future missions. Jobs and reputation are equally at the centre of Egan’s chapter, which considers the extent to which disputes around libels could change one’s status, identity and work prospects. In a similar vein, Steinberger’s analysis of a French periodical highlights the connections between miraculous and sometimes monstrous occurrences and actual social conditions, particularly those of women.

Returning across the channel, Reiter outlines how the question of fiction and imagination was problematized in a setting of confessional conflict and philosophical innovation. His chapter exemplifies the way that, in this Supplement, fiction and disinformation are at once ideas circulating in society — ideas connected to shared histories of thought and poetics — and phenomena produced socially and materially within specific contexts: a matter, in other words, for social and intellectual history at the same time. Two recent volumes that ask ‘What is History Now?’ divide the discipline into a sequence of sub-specialisms.96 Bringing together some of these different areas of history (intellectual, social, literary, cultural and so on) has been a crucial part of the project of this Supplement. This might be facilitated by study of any broad thematic topic or general overview of a period, but is certainly necessary in a coordinated treatment of fiction and disinformation. The volume also shows that literary questions (not just literary sources) are pertinent outside the historical silos where they have most commonly appeared — that is, in literary and intellectual histories. Take the matter of genre: a wide range of them appear here, beyond the classic sites of fiction and disinformation that are newspapers and the novel. The overall picture is one in which major literary works stand alongside treatises, letters, legal documents and so on, from different countries and at different times.

As a whole, the nine chapters collected here cannot be said to be representative of the early modern period, not least because of the omissions of coverage mentioned above. Yet one thing that the Supplement does is to show a series of phases within the broader period that can be differentiated from one another — longer phases such as Caravaggio’s life and afterlives (Gage) and shorter bursts, such as the eighteenth-century London newspaper scene (Dabhoiwala) that may be the end, or beginning, of an era. Similarly, part of Butterworth’s contribution is to contextualize a shorter-term crisis of religious conflict and the ‘fake news’ pamphlets that accompanied it in a longer history of writing on news and information, and therefore to rethink the entire period. An especially lively interaction of fiction and disinformation can indeed be understood as symptomatic of a crisis that will either subside or be resolved, but this volume also shows subtler elements of their everyday coexistence, as in the case of Egan’s libels. In the end, although there may be flurries of fiction and disinformation published at especially disordered moments, what we find across these chapters is an account of the early modern period where such stories and fabrications are commonplace: not only clustering around crises, but part of the broader fabric of early modern life.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by Past & Present 257, Issue Supplement 16 (November 2022, 1-35), Oxford University Press, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.