Unpacking the role of lying and truth-telling in monastic culture.

By Dr. Jay Diehl

Associate Professor of History

Long Island University

Abstract

This paper investigates the links between teaching and discourses surrounding deceit and truth-telling in eleventh- and twelfth-century monastic culture. It focuses on two manuscripts produced in the twelfth century: Brussels, KBR MS 10807-11 from the abbey of Saint Laurent in Liège and Douai BMDV 267 from Saint Rictrude at Marchiennes in Arras. Taking these manuscripts as a point of departure, this chapter suggests that they situated the act of truth-telling not only as the result of good pedagogy, but as itself a form of pedagogy. I will analyze what was at stake in both deceitful and honest speech in monastic culture and investigate how and why such behaviour could operate as a form of pedagogy in religious communities.

Introduction

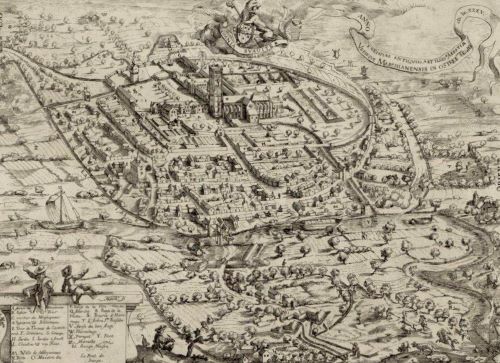

‘There is a great question about lying’, says Augustine at the beginning of his treatise On Lying, ‘… whether we may decide that sometimes lying is good, through a sort of honest, well-intended, or charitable lie’.1 Here Augustine posed what he considered to be the fundamental question concerning lying: whether it could ever be ethically justified.2 Twelfth-century monks, reading the text some 800 years later, would have been confronted with this question at its outset. There is, however, very little indication that they found it the most compelling part of the treatise. Most monastic sources of the High Middle Ages that touch on the subject of lying and truth-telling simply take it for granted that lying was a vice that ought to be avoided. Still, they clearly found something about the text itself interesting, as demonstrated by the numerous manuscript copies that can be found scattered throughout Benedictine communities in northern Europe. This study takes as its point of departure two of those copies, both produced in the southern Low Countries in the twelfth century. The f irst, Brussels, KBR (formerly: Royal Library of Belgium) MS 10807-11 (hereafter KBR 10807-11) is from the community of Saint Laurent in the city of Liège and was produced around the year 1100. The second, Douai, Bibliothèque Marceline Desbordes-Valmore MS 267 (hereafter BMDV 267) is from the community of Saint Rictrude at Marchiennes in the diocese of Arras and was probably copied sometime between 1150 and 1160.

The goal of this study is to use the texts contained in these manuscripts and the histories of the manuscripts themselves as vehicles for unpacking the role of lying and truth-telling in monastic culture and to explore its significance for the history of monastic learning, particularly with respect to ethics. The first section briefly examines the two Augustinian texts that served as touchstones for medieval discussions of lying. Turning to the twelfth century, I suggest that, in monastic culture, Augustine’s ideas became a key part of a discourse that situated all speech acts as inherently pedagogical, transforming a monastery into a community of individuals who constantly ‘taught’ and ‘learned’ ethical behaviour from each other through the very act of speaking truthfully (or failing to do so). Such learning was largely independent of the actual information imparted by a truthful statement, depending instead on the virtue and discipline manifest in the statement itself.

In the second section I return to the manuscripts and investigate a basic question: in a culture in which ethical behaviours such as truth-telling were fundamentally embodied and experiential forms of cultural practice, what was at stake in consigning knowledge of them to written texts? By examining the circumstances at Saint Laurent and Marchiennes, I will suggest that conflicts at both monasteries led to a sort of ‘crisis of trust’ that rendered members of these communities unable to serve as models for ethical behaviour, prompting them to produce manuscripts containing texts that were intended to operate as surrogate ‘teachers’ of ethics when the communities themselves could not. The central argument of this study is thus that these manuscripts sit on the cusp of two different modes of learning, one based on embodied exemplars and one based on written texts. From this argument, I hope to offer some observations about the interaction between different forms of learning in monastic culture and the role played by communal conflict in shaping monastic learning in the twelfth century.

The Augustinian Legacy: ‘On Lying’ and ‘Against Lying’

Although different in many respects, the two manuscripts at the heart of this paper share some basic similarities. Both are relatively small books for their scriptoria. KBR 10807-11 from Saint Laurent measures only 244x159mm, making it among the very smallest manuscripts produced there in the early twelfth century. BMDV 267 is a larger book at 310x220mm, but still smaller than the standard patristic manuscript produced at Marchiennes. Both books contain a compendium of several different texts that pertain, in one way or another, to ethics and the virtuous life. KBR 10807-11 contains a genuinely idiosyncratic collection of texts: works of Chromatius on the eight beatitudes and the Sermon on the Mount; a collection of sententiae of Augustine and Jerome; a sermon of Augustine on the dangers of drunkenness; and excerpts from Augustine’s two works on the subject of lying, On Lying and Against Lying.3 BMDV 267 is a somewhat more predictable book, containing a medley of Augustinian texts, including On Christian Teaching; the sermon On Pastors; the first book of On Lying; the sermon On Avarice and Luxury; two anti-heretical works; and his exhortatory letter to Darius Comes.4 Although their collections of texts differ, both manuscripts present to their readers a compact handbook of basic Christian ethics, with the problem of lying singled out as the particular vice to which the most space was dedicated.

The two texts on lying found in the manuscripts, Augustine’s On Lying and his Against Lying, are dense works that cumulatively formed perhaps the primary framework within which twelfth-century discussions of the ethics of lying took place.5 Delving into Augustine’s ideas about lying offers some initial insights as to why it may have been a particularly urgent problem for a Benedictine community and what was at stake in constructing a manuscript around that issue. On Lying is the earlier and, by Augustine’s own admission, the more difficult and obscure of the two texts.6 Its composition was prompted by Augustine’s reading of Jerome’s commentary on Paul’s letter to the Galatians, in which Jerome suggested that Paul purposefully included a lie in the text for the purpose of instructing his readers.7 In On Lying, Augustine set out to refute the existence of lies in scripture and, more generally, to investigate the ‘great question about lying’, that is, whether it is sometimes permissible to tell a lie, one that is in some sense ‘honest’ and ‘charitable’.8 Augustine emphatically denies that there is any such thing as a useful or justifiable lie. However, the details of his argument reveal important features of the cultural practice of lying and truth-telling in Augustine’s day and amongst his intellectual and spiritual heirs. He opens his investigation by trying to define a lie, which, Augustine hastens to note, is not at all the same thing as stating something untrue: ‘For not everyone who says something false lies, if he believes or considers his statement to be true’. On the contrary, according to Augustine, ‘whoever states something that he holds in his mind as belief or opinion, even though it might be false, does not lie. This he owes to the faith of his statement, such that he produces through it that which he holds in his mind …’.9 Making a false statement is, to be sure, a fault in Augustine’s mind. However, the fault is not a lie but, rather, the rash error of accounting something ‘unknown’ to be ‘known’. A liar, by contrast, is one:

who has one thing in his mind and states something else in words or by signs of any kind. Whence it is that the heart of one who lies is said to be double, that is, there is a double-thought: one of that thing which he knows or believes to be true and does not bring forth; the other that he brings forth in its place, knowing or thinking it to be false. Thus it may be that he can state something false and not lie, if he thinks it to be as he says although it is not so; and he may state something true while lying, if he thinks it to be false and speaks it as it were true …10

In the final reckoning, a lie is the product of the intent to deceive, not the truthfulness of a statement.11 As Augustine sums up: ‘Therefore, from the sense of his own mind, not from the truth or falsity of the things themselves, is he to be judged to lie or not to lie’.12 The key point here, obvious as it may be, is that lying is not an epistemological issue for Augustine; it is completely divorced from the objective truth-value of any given statement. Rather, lying is an ethical issue, bound more to moral norms than to truth.

Augustine does hedge somewhat on this basic definition, asking whether it might be possible to lie in the absence of any will to deceive. The convoluted scenario that Augustine concocts to test this theory involves the case of a person speaking something false, knowing it to be false, and yet also knowing that his listener will not believe him. In such a case, Augustine wonders, is it not the case that someone is lying ‘with the purpose of not deceiving, if lying is to state something other than you know or think it to be’.13 The contrary case also troubles Augustine: whether it might be possible to lie while stating something that you believe to be true? In this case, Augustine envisions someone speaking something that is both true and believed by them to be true, all the while knowing that his listener will again not believe them. In this case, one might ‘speak truth so as to deceive, for he knows or reasons that what is said will be thought false, just because it is spoken by him’.14 Whereas the first scenario involves knowingly stating a falsehood so as not to deceive, this case involves knowingly stating the truth so as to deceive. Which of these two are lies?

This is no small problem for Augustine, as it seems to frustrate his goal of arriving at a clear definition of a lie. He devotes a great deal of space to debating the matter before finally, one senses, in frustration, declaring that the best option is just to avoid stating things either knowing them to be false or intending to deceive: ‘All rashness and all lying will be avoided when we state, as needs be, something we know to be true and worthy of belief and we wish to convince someone of what we state’.15 To wrap up his labyrinthine definition of a lie, Augustine f inally notes that, even if we utter something false believing it to be true, but with no other aim than to make someone believe our statement, still it is not a lie, ‘for none of these definitions needs to be feared when the mind is well conscious of itself to be saying that which it knows or thinks or believes to be true …’.16 Despite his winding attempts at defining a lie, Augustine f inally reveals what he believes to be the essential problem with lying and why it requires careful def inition. It has nothing to do with the spreading of false information and everything to do with the danger posed by sinful or immoral behaviour to individual reform and salvation, which necessitates acting in good conscience more than ensuring the accuracy of one’s knowledge. When a lie is uttered, the victim is not the one who believes the lie. It is the liar themself who suffers the self-induced consequences of wrongful behaviour. Augustine’s philosophizing on the nature of lies is at least partially pastoral, in that his goal is to help people avoid sin.17

Augustine builds his argument that no lie is justifiable on two conceptual cornerstones. First, that a lie is primarily the product of intention, the willful desire to deceive, making it a problem of ethical behaviour. Second, that the main ethical concern with lying is not the dangers posed by the dissemination of false information but, rather, the inherent wrongness of the act itself and the danger it poses to virtuous living. Accordingly, he argues for the need to understand what constitutes lying so as to avoid it. Augustine develops this argument by considering a multitude of cases, many of them drawn from the Bible, in which it would seem useful to lie, ultimately rejecting all such cases as examples of behaviour to be condemned rather than imitated (or as allegory, in some cases).18 Telling a lie to save a life is not justified: ‘since eternal life is lost by lying, a lie must never be said on behalf of a temporal life’.19 Nor is it safe to lie to preserve bodily purity, as ‘there is no purity of body save that which depends on purity of mind; if the latter is broken, the former falls by necessity’.20 No good can be achieved through sinful behaviour.

In seeking to help people avoid lies, in a passage that became perhaps the most famous and widely cited section of the text, Augustine also provides a typology of eight types, so that they may be recognized and avoided. Among them we find the ‘capital lie … done in the doctrine of religion’; the lie that hurts some man unjustly, ‘such that it prof its no one and hurts someone’; the lie done only for ‘lust of lying and deceiving’; the lie done ‘with desire of pleasing by agreeable small talk’; and the lie ‘which hurts no one and does good in preserving someone from corporeal defilement’.21 None of these, no matter how banal or apparently benef icial, justif ies sinful behaviour.

This insistence that no good can ever come from lying is connected to another recurrent theme of the text, one that has not received much commentary: the link between lying and teaching. Based on Augustine’s arguments, one apparently common justification for lying was that it could be useful in teaching.22 For instance, one might think it justifiable to lie to students so as to convince them of the dangers of lust, thus preventing potential sin through deceit. This will not do for Augustine. For one, deceit as part of a pedagogical strategy comes with all the usual problems of lying, that is, that it is not worth spiritual corruption to preserve bodily integrity. However, it also comes with other dangers, ones particular to the use of lies to teach, which Augustine explains in a dense and important passage. According to Augustine, someone who lies for the purpose of teaching does not realize that:

the authority of the doctrine is cut off and perishes entirely if those whom we are trying to lead to that doctrine are persuaded by our lie that it is sometimes right to lie. Since the doctrine of salvation consists partly of things to be believed and partly of things to be understood, and that it is not possible to reach those things that are to be understood unless first believing those things that are to be believed, how is it possible to believe someone who thinks it is sometimes right to lie, lest perhaps he is lying while teaching us what to believe? For how can it be known whether he has some cause, as he thinks, for a dutiful lie, reckoning that by a false story a man might be frightened away from lust and, in this way, deem himself to be advising spiritual things through lying? This kind of lie, having been admitted and approved, subverts the teaching of faith entirely … And thus all doctrine of truth is lost, ceding its place to most licentious falsehood, if a lie, no matter how dutiful, opens the door for falsehood.23

The problem here, as Augustine sees it, is twofold. First, if a teacher uses lies to impart a lesson, and the lie is eventually discovered, the students will henceforth be unsure when the teacher is telling the truth and when he is lying, thus subverting the possibility of understanding truth. In other words, well-meant lies by teachers run the risk of undoing the bonds of trust that are necessary for good learning. Second, if a teacher uses a well-meant lie to teach the danger of, for instance, lust, the student will still learn that lying can be good for spiritual purposes and thus come to believe that lying can be beneficial in the right circumstances. From this starting point, lying would be authorized as a general practice, exacerbating the subversion of truth. For Augustine, lying is intrinsically bad pedagogy, not because it necessarily teaches untrue things but because the act itself models sinful behaviour for the student, suggesting to them that lying is permissible. The link between lying and failed pedagogy is rooted in the fact that students learn not only from the knowledge imparted by the teachers but also from their teacher’s conduct and personal ethical code.24

The idea that lying or truth-telling has an inherent pedagogic value is one that is latent throughout Augustine’s other work on lying. Against Lying, written some fifteen years after On Lying, addresses a related but ultimately more targeted question: whether it might be permissible for orthodox Christians to pretend to be heretics so as to infiltrate a sect and win its adherents back to orthodoxy.25 Or, in more general terms, was it acceptable to lie to turn heretics away from their errors? Augustine answers this question fairly succinctly in the text’s opening, stating that the only reason to track down heretics is to teach them the truth or, at least, convict them by the truth, erasing their lies and increasing God’s truth. In this case, Augustine asks, ‘how therefore am I able to rightly persecute lies by a lie?’26 The answer, of course, is that you cannot do so. The cause of orthodoxy can hardly be advanced through sin, nor can the truth be defended through lies.

The problem of using lies to teach the truth structures much of the following discussion. For example, Augustine notes that ‘when we seize liars by lying, we teach worse lies’.27 For one thing, if an orthodox lies so as to gain the truth of a heretic and win them back to orthodoxy, they must eventually admit they were lying and then attempt to teach the truth. In that case, Augustine notes, ‘who knows for certain whether … [heretics] would wish to hear teaching from one whom they have experienced lying?’28 Clearly echoing the sentiments of On Lying, this statement suggests that lying makes good teaching impossible because it eliminates trust between parties. While much of the text does focus on the danger that lying poses to the orthodox, Augustine never loses sight of the fact that this danger is linked to the fact that lying itself will teach heretics that it is acceptable for them to lie, advancing the cause of heresy rather than combating it. As he states, ‘for through this lie we will become perverted, and [the heretics] will be only half-corrected, because they think it right to lie on behalf of the truth, which we do not correct in them because we learn and teach the same thing and decree it to be proper’.29 No matter how many heretical errors orthodox Christians might correct through lies, lying ultimately fails to advance orthodoxy in that the act itself teaches the heretic to lie.

As with On Lying, Augustine also devotes considerable space in Against Lying to refuting the idea that Scripture provides any precedent or justification for lying (a position he accuses heretics of adopting). Explaining away some biblical examples of lying as figurative allegory and others as examples of poor behaviour to be emended, he concludes that any apparent instances of lying in the Bible, ‘are either not lies, but are only thought to be so while they are not understood; or, if they are lies, are not to be imitated because they cannot be just’.30 Interestingly, however, Augustine returns explicitly to the problem of teaching in the final passage of the text, leaving his readers with the statement that, ‘either lies must be avoided by action or confessed through penance; however, they are not to be increased through teaching when they unhappily abound in our living ’.31 Teaching, as it turns out, not only fails to justify lies but also is perhaps the most dangerous milieu for them. Augustine’s conclusion reveals that in many ways, Against Lying is fundamentally an exploration of the link between lying and teaching, arguing against the pedagogic value of lying.

Heirs to the Augustinian tradition of thought on lying received a conceptual framework built around several fundamental themes. First and foremost was the idea that lying and truth-telling were ethical problems, whose chief danger was not the dissemination of false information but spiritual corruption. Second, there was no such thing as a good lie, no matter how trivial or beneficial it might seem. Third, any and all scriptural examples of lying were either figurative or intended to show forms of behaviour requiring correction. Finally, there was the connection between lying and teaching. Not only were lies not permissible in the interests of teaching but also they represented intrinsically bad pedagogy. On one hand, they disrupted the atmosphere of trust necessary for teaching the truth. On the other hand, the very act of lying itself represented the teaching of unethical behaviour, as students would learn from their teacher that lying was permissible and, in certain situations, even desirable. Sitting at the confluence of ethical behaviour, scriptural precedent, and teaching by example, the practice of lying and truth-telling was embedded in precisely the sort of issues that became central to medieval monastic culture.

Speaking, Lying, and Truth-Telling in Twelfth-Century Monastic Culture

Twelfth-century thinkers were much influenced by Augustine’s views on lying. As Marcia Colish has demonstrated, urban schoolmasters and scholastic theologians frequently debated Augustine’s assertion that there was no such thing as a beneficial lie.32 Because Augustine’s argument concerned sin, his ideas were eventually transmitted via scholastic thinkers into clerical texts on pastoral care in the thirteenth century.33 Scholastic theologians, however, were not the only heirs to the Augustinian tradition of thought on lying. Although monastic thinkers seem never to have engaged with Augustine’s ideas on lying as explicitly as did schoolmasters seeking quaestiones for disputation, monastic communities were nonetheless important recipients of Augustine’s ideas, as indicated by the surviving manuscripts from Saint Laurent, Marchiennes, and many other communities.34

Within monastic culture, ideas about lying and truth-telling were received not just as interesting and diff icult questions on sin and ethics to be resolved but also as questions fundamental to daily life. From the earliest days of Christian monasticism, speech was treated as a key component of the disciplinary regime of the monk, an idea that became an integral part of monastic spirituality in the High Middle Ages. In the Latin tradition, the Rule of Benedict was the wellspring and primary conduit through which the idea of disciplined speech was transmitted. The sixth chapter of the Rule states that, given that there are times when even ‘good speech’ should be left unsaid out of esteem for silence, evil speech is all the more to be shunned, so as to avoid punishment for sin.35 Silence, then, was the gold standard for speech acts in monastic culture, such that even advanced monks should only seldom be given permission to speak, even if their words were good and constructive.36 Interestingly, this chapter ends by stating that ‘speak-ing and teaching are fitting tasks for the master; it is appropriate that the disciple be silent and listen’.37 Echoing somewhat Augustine’s thoughts on lying, Benedict’s Rule suggests an inherent connection between speech and teaching. Speech itself, as a form of practice, was appropriate for teachers not necessarily because the content of their speech was laden with better knowledge but because they had achieved the level of self-mastery necessary for good speech. Speaking defined teachers, and teachers were the ones who spoke, while silence was for learning.

It is difficult to overstate the influence of this idea within monastic texts of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. It can be found, albeit in diverse forms, within devotional literature, hagiography, and quasi-normative sources such as customaries. Scott Bruce’s investigation of silence and sign language in the Cluniac customaries of Bernard and Ulrich, among the most influential such documents, reveals that speech was forbidden at nearly all times and places, and particularly during the canonical hours. Indeed, Ulrich outlined only two brief periods during which conversation was allowed, and then only with supervision (a sign again of the link between speech acts and pedagogy). This rigidity was part of a general and nearly unprecedented Cluniac regard for silence, which grew out of the conviction that it both avoided sinful speech and was itself a positive spiritual practice.38 Ulrich’s customary surely ref lected the ideals more than the lived reality of monasticism, Cluniac or otherwise. Nonetheless, regulated, supervised, and disciplined speech was central to his vision of monastic spirituality.

The same ideals can be found within devotional literature. The English Cistercian abbot Aelred of Rievaulx was one of the more eloquent spokespersons for disciplined speech. His Pastoral Prayer, in which he asks for the strength and tools to govern the monks of Rievaulx, requests that God, ‘place true and right and good sounding speech in my mouth […] built on faith, hope, and love […] in patience and obedience’.39 Speech also plays a vital role in a passage found in Aelred’s lament for his dead brother Simon found at the end of Book One of the Mirror of Charity: ‘the authority of our order barred us from speaking, but his appearance spoke to me, his walk spoke to me, his very silence spoke to me’.40 So powerful is the idea of disciplined speech in this passage that it is a core component of monastic life and also serves as a metaphor for the entirety of Simon’s disciplined self. This passage also illuminates another feature of the monastic culture of speech that is less evident in the customaries: its performative dimension. Simon’s discipline and, in particular, his silence were on display for Aelred. The Mirror of Charity makes it clear that Simon’s demonstration of proper monastic ethics served as an inspiration for Aelred’s own life. As Aelred wrote, ‘I remember that often, when my eyes began to wander hither and thither and, having glimpsed him only briefly and being flooded with such shame, I would restrain all that fickleness and, gathering myself, begin to occupy myself in something useful’.41 Aelred’s relationship with Simon reveals something fundamental about ethical behaviour in monastic culture: it not only benefitted the one enacting it but also served as a model for others who were attempting to maintain the rigors of monastic discipline. To act in accordance with monastic ethics was to teach those ethics. To speak well was to teach good speech, an observation that draws us back to the problem of lying in monastic culture.

Lying, to be sure, was never as worrisome as certain other sins in twelfth-century monastic culture. Consider a bit of evidence from the monastery of Saint Laurent itself. In the early twelfth century, contemporaneous to the production of KBR 10807-11, scribes at Saint Laurent added a list of vices and virtues to the front of a manuscript containing Jerome’s commentary on Daniel and Bede’s commentary on the canonical epistles.42 Several of the listed vices and virtues were written in majuscule script, making them stand out on the list and giving them a heightened sense of importance. Among those so singled out were ‘Envy/Charity’ (Invidia/Caritas), ‘Anger/Patience’ (Ira/Patientia), ‘Violence/Peace’ (Rixa/Pax), ‘Avarice/Generosity ’ (Avaritia/Largitas), ‘Gluttony/Abstinence’ (Ingluvies/Abstinentia), and ‘Luxury/Chastity’ (Luxuria/Castitas). Here perhaps is a convenient snapshot of the most dangerous vices and the most desirable virtues for the community at Saint Laurent. It would hardly be surprising if this list was ref lective of the broader ethical priority of twelfth-century monastic communities. Certainly abstinence, chastity, and charity are well known, even obvious priorities for monastic communities, and Lester Little has demonstrated that anger and patience were important virtues around which monastic identity was constructed.43 The issue of truth-telling and lying does appear on the list in KBR 10260-63 in the form of the binary ‘Falsehood/Truth’ (Fallatia/Veritas). But it was not given the same emphasis in the manuscript as other vices and virtues.

Nonetheless, the issue of lying and truth-telling occupied a place of particular urgency in the ethical landscape of monastic culture. This urgency stemmed from the fact that the problem of lying was integrated into the broader problem of disciplined speech, which set it apart from other affective sins of intention such as envy. On its own, lying may never have been considered as dangerous as gluttony or anger in monastic life. However, when joined to the broader problem of speech and silence, it became an aspect of one of the basic pillars of monastic discipline. And it was within the context of disciplined speech that many monastic writers discussed the dangers of lying. For instance, Hugh of Saint Victor devoted a chapter of his On the Instruction of Novices to the issue of speaking (‘Quomodo loquendum sit’). In many ways, it mirrors the discussions of speech found in Benedict’s Rule and monastic customaries. But Hugh also addresses the particular danger of false speech and lying in his discussions, citing Scripture: ‘Harsh and quarrelsome words should be removed entirely from disciplined speech (sermonibus disciplinatis), as is proven by that passage that says, “the lips of a fool are mingled with strife and his mouth provokes quarrels” (Prov. 18:6)’. It also emphasizes that mendacious words must be avoided: ‘A false witness will not go unpunished and he who speaks lies will not escape’ (Prov. 19:9).44 For Hugh of Saint Victor, the problem of lying was inseparable from the broader issue of regulated speech, and it was this connection that shaped the ethical imperative against lying.

Among the many twelfth-century monastic writers who discuss lying in the context of disciplined speech, Peter of Celle may be the pre-eminent example. In one of his sermons for Passion Sunday, Peter uses one of the medical metaphors dear to twelfth-century monastic writers by comparing the various monastic virtues to the ingredients for a curative drink. ‘Consider’, he says, ‘the regiment of this potion: silence, abstinence, chastity, humility, charity, obedience, a calm mind, removal of immoderate jesting, and tranquility. All these pertain to the observance of this drink and it does not confer health without them; he who receives it according to some other recipe is not purged by it, but killed’.45 It is a list of virtues that is clearly reminiscent of that found in the manuscript described above. He then describes the various vices that are prevented by the cultivation of each virtue, beginning with silence: ‘Silence prevents lying, foolish talk, buffoonery, and all idle chatter’.46 Like Hugh of Saint Victor, Peter of Celle treats lying as a subspecies of bad speech acts and considers it within the broader rubric of the kind of speech appropriate to the monastic life. Interestingly, Peter seems to give both silence and lying more priority than the other sources considered here. The former is the first virtue in Peter’s recipe for monastic life, while the latter is the first vice that is avoided through silence. Furthermore, and somewhat remarkably, his framework implicitly suggests that the antithesis of lying is not truth-telling but silence. Peter makes a similar point in his famous School of the Cloister, where the chapter on silence notes that it prevents idle words, deceptive words, and dishonest words, as well as schismatic and heretical murmurings.47 This re-imagined binary – lying/silence in place of lying/truth-telling – signals the extent to which the problem of lying had been absorbed into the monastic culture of disciplined speech.

Monastic culture thus served as a point of convergence for two traditions, one having to do with the ethics of lying itself and one that situated all speech acts as part of a disciplinary regime intended to avoid sin. Importantly, both emphasized that there was a link between speech and pedagogy that transcended the simple information conveyed by speaking and emerged from the ways in which good speech served as an exemplar of proper conduct. Each tradition implicitly recognized that speech occupied a special place within the field of ethical behaviour, one that stemmed from the fact that speaking is by nature both public and performative.48 Whereas sins of intention such as greed or lust were grievous faults, they might well be confined to the interiorized self of the sinner, never visible to anyone else. Sins of speaking, including lies, were on display for others to witness. Bernard of Clairvaux seems to have had this point in mind in the vignette of the boastful monk found in The Steps of Humility and Pride. Much of the portrait focuses on how the monk will never stop talking. When discussing literature, ‘he brings forth old things and new. Opinions f ly forth, puffed up words resound. He jumps in before the question, he does not answer those who are questioning. He asks, he solves, and he completes the unfinished sentences of others’.49 The boastful monk is one who cannot stop himself from talking (and, notably, Bernard sees silence as the cure for boasting). Note, however, that the entire scenario requires an audience. The boastful monk is ‘hungry and thirsty for listeners, with whom he bandies about his vanities, to whom he pours out all that he thinks …’.50 His goal is ‘not to edify anyone, but to show off his knowledge. He is able to edify, but he does not intend to do so. He cares not to teach you, nor to be taught what he does not know by you, but only to know that it is known what he knows’.51 To speak badly, there must be someone to listen to you. As a result, a lie – or any form of bad speech – does a sort of double-damage peculiar to sins that require an audience. A lie is a sin in and of itself on the part of the liar, but it also represents a failure to model proper behavioural norms.

But the opposite is true as well. If the public nature of lying made it particularly dangerous, so too did it make truth-telling all the more valuable. The value accorded to truth-telling was the lasting legacy of the ways in which the Augustinian ethical framework for lying and the monastic culture of disciplined speech intermingled with each other. Their combination transformed truth-telling into a cultural practice that was simultaneously ethical, spiritual, and pedagogical. Speaking truthfully was an ethical act in and of itself, part of properly disciplined monastic speech. But it was also a pedagogical act that taught ethical behaviour to the rest of the community. In a rather different context, we catch an echo of this ideal once again in Bernard of Clairvaux, this time in his On Consideration. Discussing the problem of litigious suits and disputes brought by advocates and other secular officials, Bernard unleashes his scorn on those who ‘have taught their tongue to utter lies; they are skilled in opposing justice, learned on behalf of falsehood. They are wise so that they might do evil, eloquent so as to assault the truth. These are the sorts of people who instruct those by whom they should be instructed … Nothing makes truth so easily apparent as a brief and simple narrative’.52 Bernard here suggests that those who speak the simple truth should be accorded the status of teachers, but not on account of their eloquence, training, or erudition. Indeed, if anything, they are less learned than those who lie, transforming their sophistic education into a tool for deception. Rather, they are teachers because they speak truthfully. If Augustine had suggested that teaching required one to avoid lies and speak the truth so as to avoid teaching bad ethical behaviour, twelfth-century monastic writers pushed this idea a little further such that truth-telling itself became positive pedagogy. Every instance of truth-telling both reproduced a culture of ethical speech and also laid the groundwork for it to be reproduced by others, making every monk who participated in the monastic culture of speech not only a student of ethics but potentially also a teacher of it. And every lie was not only a breach of ethics but also a failed ‘teachable moment’.

This approach to learning ethics was embodied, performative, and generally hierarchical, as greater mastery of discipline transformed one into a suitable exemplar for others. It is learning enacted through the very speech acts of every member of a monastic community, based not (only) on absorbing the content of speech but on internalizing and ultimately re-enacting its disciplinary value. Yet this particular culture of ethical pedagogy, the existence of which has been noted by numerous scholars, reveals an apparent paradox: if a culture of truth-telling was supposed to be enacted and ‘taught’ through the speech of the members of a monastic community, why did they need books like KBR 10807-11 or BMDV 267? Why have written texts teaching the ethics of lying when you have living individuals as models? The easy, and perhaps most intuitive, answer is to suggest that the two teaching methods do not really have anything to do with each other at all; they represent two different forms of cultural practice – one perhaps more intellectual, the other more experiential – and need not be read within the same context. But another possibility exists as well, one that links the production of such manuscripts to the culture of pedagogical speech. It emerges if we look at the circumstances in which KBR 10807-11 and BMDV 267 were produced.

Written Ethics in a Performative Culture

However different Saint Laurent around 1100 and Marchiennes in the 1160s might have been, there are enough similarities in the circumstances in which KBR 10807-11 and BMDV 267 were copied to warrant comparison, beginning with the story of Saint Laurent and the production of KBR 10807-11. Founded largely through episcopal initiative (with the aid of the monastic reformer Richard of Saint Vanne), the community at Saint Laurent was closely allied with the bishop of Liège for most of its history.53 Henry of Verdun, bishop from 1075 to 1091, was a particularly strong supporter of the community but also an interventionist one. Two years after becoming bishop, he deposed the then abbot of Saint Laurent, Wolbodo, whom later sources accuse of pride, profligacy, and a secular lifestyle.54 Wolbodo’s replacement, Berengar, was recruited from the abbey of Saint Hubert in the Ardennes, a community with close ties to Saint Laurent.55 For the remainder of Henry’s episcopacy, both communities and the bishop enjoyed good relations. In 1091, however, Bishop Henry died, and Emperor Henry IV chose Otbert, a former provost of the church of Liège who had been exiled by Henry of Verdun, as the next bishop. Otbert immediately sought to ensure the loyalty of all the major monastic communities of the diocese, deposing abbots and replacing them where necessary. Berengar was among his targets, deposed in 1092 and replaced with the previously deposed abbot Wolbodo.56

Like Wolbodo, Berengar did not take his deposition lightly and formulated a long-term strategy to return to Saint Laurent. He was sheltered first at his former community at Saint Hubert and then at the priory of Evergnicourt in Reims. At least some of the monastic community of Saint Laurent accompanied Berengar into exile rather than profess obedience to the ‘pseudo-abbot’ Wolbodo and Bishop Otbert.57 For some three years this group remained in exile, working to gain the support of ecclesiastical and secular rulers. Sources also suggest that support for Wolbodo at Saint Laurent grew cold, leading additional members of the community to join Berengar in exile in Reims.58 Pressured by the secular nobility of Liège, Otbert finally relented in 1095 and invited Berengar to return.59 Despite the fact that Otbert was excommunicate at the time, Berengar agreed to reconcile with Otbert, received his abbacy back from the bishop, and the exiled monks returned to the abbey of Saint Laurent.60

KBR 10807-11 was thus produced at one of the most challenging moments in the community’s history and, along with some of the numerous other manuscripts produced during the same period, may well have been copied in response to these events.61 In the aftermath of these, the community was likely fractious and factionalized. While it is possible that all of the monks of Saint Laurent eventually joined Berengar in exile, some of them would have spent only months there, while others had spent three years away from Liège. Among the people now living together were the group of monks who had originally refused obedience to Wolbodo and Otbert and had gone into exile from the start; some unknown number who had joined them; and perhaps some who had never gone into exile at all. Berengar too, as Tjamke Snijders and Steven Vanderputten have suggested, was in a difficult position, having refused at first to treat with Otbert but ultimately having relented and reconciled with him. Such an act may well have been viewed as hypocrisy (and it is worth noting that Augustine held that hypocrisy was a form of lying, a lie of ‘deeds’ rather than ‘words’).62 For a period of three years, the members of the monastic community at Saint Laurent had pursued a variety of strategies and agendas in response to Otbert’s deposition of Berengar, and it may not be a stretch to suggest that after the reintegration of the community, individuals would have viewed those who had pursued different paths with suspicion and had a difficult time trusting them. At the very least, the bonds of trust that would normally, or at least ideally, tie a community together would have been badly frayed.

The situation at Marchiennes in the 1160s was different, to be sure, but no less complicated. The community of Saint Rictrude at Marchiennes, founded in the seventh century as either a female community or a mixed community, was reformed into a male Benedictine community under the aegis of Gerard of Cambrai and Leduin of Saint Vaast in 1024.63 It flourished until the problematic abbacy of Fulcard (1103-1115,) who, according to surviving sources, nearly brought the community to ruin.64 The community then came under the eye of the fiery reformer Alvisus, abbot of Anchin, who targeted the abbey as part of his broader strategy of Benedictine reform and network-building in the southern Low Countries.65 In 1116, Marchiennes was reoccupied by the prior of Anchin and pupil of Alvisus, Amand de Castello, who reinvigorated the religious life there.66 But he also tied Marchiennes tightly to Anchin, placing it in an effectively subservient position to the currently more prosperous and influential abbey, setting the stage for an eventual conflict between Marchiennes and Anchin, the latter backed by Alvisus, who was elected bishop of Arras in 1131.67

This conf lict, however, was a long time coming. The abbacy of Amand de Castello passed in relative peace, as did that of his successor Lietbert (1136-1141), another monk of Anchin. Nonetheless, as Marchiennes recovered its material security and prestige, the community at large strove to liberate itself from Anchin’s shadow. These efforts placed the abbots of Marchiennes, who were close allies of Bishop Alvisus, in a difficult position. Lietbert resigned the abbacy in 1141, perhaps to avoid a looming showdown with the bishop.68 But far from preventing such conflict, Lietbert’s resignation effectively sparked it. The monks at Marchiennes elected a certain Odo as their next abbot, against the wishes of Alvisus, who insisted that Lietbert be reinstated.69 Seeking an authoritative backing for their own duly elected abbot, the monks of Marchiennes sent a delegation to the pope, who responded with a letter affirming the right of the community at Marchiennes to elect its own abbot, condemning Alvisus, and ordering him to appear at a papal court.70 The delegation, of course, took time to travel to and from Rome, and Alvisus in the meantime had tried to placate the community at Marchiennes by offering three candidates for abbot from whom to choose, thus allowing the monks some agency while retaining control over the election. The community selected one of them, Hugh, and the dispute might well have ended there with a compromise candidate. However, when the delegation from Marchiennes returned from Rome with the pope’s letter in hand, Hugh promptly resigned the abbacy and left the community in limbo once again.71

It was not until 1142 that something akin to a resolution was achieved. At the council of Lagny, Alvisus repented of his interference in the affairs of Marchiennes and allowed the community’s original choice for abbot, Odo, to reassume his position. The pope issued a pardon to Alvisus, leading to a reconciliation between bishop and both Benedictine communities, all of whom remained closely linked.72 Nonetheless, the fallout from these events seems to have lasted for years. Odo resigned as abbot of Marchiennes after only one year. His successor, Ingran, lasted somewhat longer, but he also resigned under suspicious circumstances in 1148. It was only under his successor, Hugh II (1148-1158), that true stability seems to have returned to the community at Marchiennes.73 It is likely that BMDV 267, along with many other manuscripts, was produced during the abbacy of Hugh II.74

The troubles faced by Marchiennes and Saint Laurent differed in many particulars, most notably the lack of a fully realized communal schism in the case of the latter. Still, there were important similarities as well. Both involved attempts by monastic communities to liberate themselves from episcopal meddling. Both involved disputes over the abbacy of the community and an extended period of confusion and uncertainty as to whether a particular individual was, in fact, the legitimate abbot. And both conflicts, once settled, were followed by an intensive period of manuscript production, very possibly part of broader strategies of recuperation and reconciliation. The case of Marchiennes may have lacked the drama of exile, but it nonetheless represented another example of corporate trauma that would have challenged the coherence of the community. And lacking coherence, mutual trust would also have been in short supply. If the crises at both Saint Laurent in 1092 and Marchiennes in 1141 seem, in many ways, typical of the sorts of political conflicts that twelfth-century Benedictine communities often faced, it is worth noting that such events could engender intra-communal ‘crises of trust’ that impacted the daily social and cultural life of a monastery.

Such situations would have had particularly important ramifications for the culture of ethical and disciplinary speech acts that were sup-posed to characterize monastic society. A failure of communal trust would have meant that members of the community would have had, at best, a limited ability to function as exemplars for each other’s ethical behaviour, particularly when it came to truth-telling. Suspicion, doubt, conflict, and schism were the Achilles’ heels of the pedagogic culture of truth-telling. Recall, for instance, that Peter of Celle grouped schismatic and heretical ‘murmurings’ among the evil speech acts that could be avoided by silence.75 In a community beset by internal conflict, however, any speech might easily be construed as problematic, schismatic, or fallacious by one group or another. In such a situation, any exemplar for teaching ethical speech had to be externalized; it could not be a person (or, at least, not a person who was a member of the community). I would suggest that KBR 10807-11 and BMDV 267 were those exemplars, written texts, depersonalized and external to the world of embodied behaviour. In the ideal form of monastic life, such texts might have been seen as sterile simulacra, preserved but lifeless representations of vivified models of ethical behaviour. But in a community where no person could be trusted to model such behaviour, it served as a surrogate, a standard by which the community could measure itself. Its usefulness lay in the very fact that it was depersonalized.

Demonstrating a clear link between the copying of KBR 10807 and BMDV 267 and the conflicts that preceded their production is a difficult and speculative business. It is worth noting at the outset that both books were produced as part of substantial programs of manuscript production that took place at both monasteries after these conflicts; intuitively, it makes sense to think of these programs as responses to the conflicts.76 However, there are more concrete reasons to interpret both manuscripts as attempts to deal with the aftermath of communal conf lict and trauma. Consider f irst the case of Saint Laurent. KBR 10807-11 was, in fact, one of a number of manuscripts containing texts on ethics, vices, and virtues produced around this time. In addition to the list of vices and virtues added to the front of KBR 10260-63 mentioned above, scribes at Saint Laurent also copied two Carolingian texts on the vices and virtues, one by Ambrose Autpertus and one by the figure usually identified as ‘Albinus Eremita’ or Albinus of Gorze, both preceded in their respective manuscripts by Isidore’s penitential Synonyma.77 One of the manuscripts also contained a copy of Julianus Pomerius’ On the Active and Contemplative Life, the third book of which discusses the principal virtues and vices.78 Additionally, they copied Isidore’s Sentences, sometimes referred to as On the Highest Good, but given the title On Virtues in this manuscript.79 The scriptorium also produced a compendium that combined doctrinal texts of Alcuin with a variety of short excerpted works on penance, the beatitudes, and key virtues of Christian life.80 Scribes at Saint Laurent were engaged in a concerted effort to produce texts on ethics at the turn of the twelfth century, and KBR 10807-11 was a key piece of this broader program.81 Such a clear, programmatic focus suggests that these manuscripts were produced with a particular goal in mind or in response to a particular set of circumstances; the exile and schism of the community would seem to be the most obvious candidate.

The textual features of On Lying and Against Lying in KBR 10807-11 also indicate that the manuscript may have been self-consciously designed to serve as a surrogate for interpersonal modes of teaching ethics. As mentioned earlier, KBR 10807-11 does not contain the entirety of either On Lying or Against Lying but only excerpted sections of both texts. On Lying is, as it turns out, quite extensively excerpted. The only portion of the text present in KBR 10807-11 is Augustine’s typology of the eight types of lie, ultimately comprising only a handful of lines in the manuscript.82 The excerpt from Against Lying is much more extensive, amounting to just over half the text, mostly from the second half. Several chapters that echo the basic argument of On Lying – that there is no such thing as a useful lie, as no good can come from sin – are prioritized. These are followed by an extensive array of chapters giving scriptural citations, either ones that clearly demonstrate the evils of lying or ones that might seem to justify lying but do not if read properly.83 The cumulative effects of these particular excerpts is the removal of all material that suggests that one of a teacher’s responsibilities is to model proper ethical behaviour for his students, including all references to the links between pedagogy and lying and, in particular, all suggestions that lying itself teaches bad ethical behaviour. Instead, readers of the manuscript are presented simply with a typology of lies and a series of objective, textual exempla that either demonstrate the evils of lying or show behaviour to be avoided. If the very existence of KBR 10807-11 hints at a mode of teaching ethics that was ‘depersonalized’, the ways in which the text were excerpted seems designed to accomplish that process. The special care that was taken to de-emphasize the idea that lying or truth-telling was itself pedagogical raises the possibility that the manuscript itself was designed to be the pedagogue, stepping in for the members of the monastic community at a moment when it was difficult to unify around any particular living exemplar.

The evidence from Marchiennes generally reinforces the picture that emerges from the case of Saint Laurent. There is also some oblique evidence that suggests that the problem of lying was embedded in the conf lict over abbatial leadership and communal independence at Marchiennes. In the midst of this dispute (and others in which he was also involved), Alvisus solicited the support of Bernard of Clairvaux. The Cistercian abbot was already favourably inclined to Alvisus’s reform efforts, given that they were largely inspired by the Cistercian model of monasticism.84 He backed Alvisus in his battle with Marchiennes by sending a letter to the pope endorsing the actions of Alvisus and condemning the monks. Of the monastic community he wrote: ‘The monks of Marchiennes have come to you with a spirit full of lies and falsehoods against the Lord and his anointed. They have made unjust claims against the bishop of Arras, whose life and conduct was hitheFurthermore, the Marchiennes copy of On Lying was clearly part of a pro-grammatic effort to textualize moral guides similar to the one undertaken at Saint Laurent. Whereas scribes and scholars at Saint Laurent focused on collecting a variety of texts on the vices and virtues, the community at Marchiennes went all-in on Augustine. In the third quarter of the twelfth century, scribes at Marchiennes copied an enormous corpus of Augustine’s works, including On Lying. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that the copy of On Lying was not simply some side-product of a broader enthusiasm for Augustine but part of a targeted effort to use a body of Augustinian texts as a foundational guide to a religiously inf lected ethical life. Consider the tenrto of good repute in all places. Who are these, who bark like dogs, who call good evil, who place light in the shadows? Who are these who, contrary to the law, speak to the deaf and place obstacles in the way of the blind?’85 There are two points worth noting in this letter. First, and most obviously, it demonstrates that, well before the copying of BMDV 267, the problem of lying had been explicitly woven into the dispute between Alvisus and the monks of Marchiennes. Second, and more generally, Bernard’s accusation against the monks of Marchiennes (one that he recanted during the reconciliation process) reveals how readily the idea of lying could be weaponized in moments of conflict.

Furthermore, the Marchiennes copy of On Lying was clearly part of a programmatic effort to textualize moral guides similar to the one undertaken at Saint Laurent. Whereas scribes and scholars at Saint Laurent focused on collecting a variety of texts on the vices and virtues, the community at Marchiennes went all-in on Augustine. In the third quarter of the twelfth century, scribes at Marchiennes copied an enormous corpus of Augustine’s works, including On Lying. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that the copy of On Lying was not simply some side-product of a broader enthusiasm for Augustine but part of a targeted effort to use a body of Augustinian texts as a foundational guide to a religiously inflected ethical life. Consider the ten surviving manuscripts containing works of Augustine that probably date from this period.86 Seven of these manuscripts contain single, complete copies of Augustine’s major theological works such as The City of God and On the Trinity or substantively complete copies of his sermons or letters.87 These seven manuscripts are also generally uniform in size and layout, about 330mm tall and 250mm wide (with two standouts that are much larger). Overall, they present a format typical of high-quality patristic books produced by twelfth-century monastic communities.

The remaining three manuscripts, however, are of an altogether different character.88 They are considerably smaller than the other Augustinian books, averaging about 290mm in height and about 190mm in width. Instead of containing complete copies of a single long text by Augustine, all three of them contain a medley of shorter works, generally on didactic, pastoral, or ethical topics. They were very likely produced in concert and represent a coherent and complementary trilogy of books. One of them (Douai BMDV 270) is a sort of primer on the value of asceticism, combining Augustine’s On Virginity; his On Seeing God; an excerpt from The City of God on the spiritual body; his Disputation Against Fortunatus, a work against Manichaean dualism; and his On Good Marriage and On Holy Widowhood, both works that dealt with Jovinian’s attacks on asceticism.89 The second book (Douai BMDV 265) contains a trio of texts that are simultaneously doctrinal and pastoral, outlining key Catholic beliefs but also detailing how those beliefs ought to operate in daily life: On Free Will, On True Religion, and On True Faith.90 The third book, which contains On Lying, may be the most interesting of the three. In addition to On Lying it contains a second work on ethics, the sermons On Avarice and Luxury, two anti-heretical texts, and Augustine’s exhortatory letter to Darius Comes.91 It also contains two works that deal with pedagogy. The first is On Christian Teaching, a standard work on modes of teaching tied to Christian belief. The second, found immediately before the copies of On Lying and On Avarice and Luxury, is Augustine’s sermon On Pastors, a work focusing on Ezekiel 34 that weaves together observations about pastoral care with insights about teaching. One of the major themes of this sermon is the necessity for ‘shepherds’ to live an upright life so as to set a good example for their followers, who often imitate their pastor in both his good and bad ways.92 This concern for the example set by good conduct probably explains the connection of On Pastors to both On Lying and On Avarice and Luxury. In fact, if one read On Christian Teaching, On Pastors, and On Lying together, they would coalesce into a textual guide for constructing precisely the sort of culture of ethical pedagogy outlined above, one that blurs the line between acting ethically and teaching ethics. Such a guide would be most useful precisely when that culture had broken down.

Cumulatively, the evidence from Saint Laurent and Marchiennes indicates that both communities experienced a traumatic conflict that would have likely divided the community or, at the very least, severely impacted its coherence. The scriptoria of both communities became highly active in the aftermath of these conflicts. Ethical texts, in one form or another, represented a key strand of textual production in the post-conflict programs of manuscript production. The copies of the Augustinian texts on lying were key parts of a concerted effort to textualize ethical pedagogy at both communities, efforts that probably responded to problems posed by communal conflict and schism. I suggest that ethical texts were attractive at these moments, not only because ethics was a topic of special importance, but also because of the difficulties such conflicts would have posed to modes of learning ethics based on performance, embodiment, and imitation. When there was insufficient concord or trust in the rectitude of the community, learning ethics by experiencing the behaviour of the community directly would have been difficult. The fact that trust was central to this problem perhaps explains why the problem of lying, not normally high on the list of monastic vices, was of particular urgency in these circumstances. The written texts about lying found in KBR 10807-11 and BMDV 267 operated as surrogate teachers of ethics in the wake of the breakdown of a culture that depended on living exemplars.

Conclusions

KBR 10807-11 and BMDV 267 sit at the intersection of two simultaneously ethical and pedagogical cultures: one rooted in the communal performance of speech acts in which all members of the community were both student and teacher; and one based on written texts. Understanding the circumstances that prompted the production of these two manuscripts helps illuminate the interplay between these two modes of learning. On one hand, they clearly represent something of a transition from a culture of learning based on living models, in which some individuals were clear authorities, to one based on disembodied texts, which flattened out the ethical hierarchy of the community.93 But several other factors suggest that the situation was not as simple as texts simply supplanting living individuals as instruments of learning. First, the value of the texts contained in KBR 10807-11 and BMDV 267 was not that they were written or textual but that they were impersonal; their lessons were not dependent on any given person’s mastery of ethical behaviour, but instead made all learners subject to the text and so placed them on equal footing. Second, the fact that the interplay between different modes of learning at Saint Laurent and Marchiennes did not involve a shift from embodied to textual ones so much as a shift from interpersonal to impersonal ones suggests that there was nothing natural or even desirable about transforming the teaching of ethical norms into a textual practice. It happened only when the performative, embodied culture of ethics that had defined these communities broke down.

Functionally then, the written texts were designed to do the pedagogic work that no member of the community was able to do. We might even say that the texts had been imbued with a particular form of educational agency by living individuals who no longer possessed it. Replacing living authoritative exemplars with written texts was a choice foisted upon the communities by a particular set of circumstances, not a goal in and of itself. The goal was to create surrogate textual models that could, insofar as it was possible, fulfill the functions previously accomplished by the members of the communities themselves and thus perpetuate a culture of ethical learning. The development of a form of pedagogy based on texts was designed not to supplant an inferior system of learning with a completely new one but, rather, to supplement or perhaps even repair a broken one. As a result, thinking of the process as a transition between two opposing forms of intellectual culture offers an overly stark and rigid picture of a dynamic and fluid situation. The production of KBR 10807-11 and BMDV 267 represented a real transformation in which ethics entered into a sphere of learning that was scholastic, intellectual, and literate. However, it is likely that the communities of Saint Laurent and Marchiennes had their eyes on the recuperation as much as the supercession of an embodied approach to learning ethics.

Endnotes

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 413: ‘Magna quaestio est de mendacio […] aut arbitremur aliquando esse mentiendum honesto quodam et of f icioso ac misericordi mendacio.’

- For a sweeping history of this question in the western intellectual tradition, see Denery, The Devil Wins.

- Described in Van den Gheyn, Catalogue des manuscrits, 2: 52-53.

- See Dehaisnes, Catalogue général des manuscrits, vol. 5: Douai, 140.

- On these works, see Griffiths, Lying: An Augustinian Theology of Duplicity; Denery, The Devil Wins, 106-119; and the trio of articles by Feehan: ‘Augustine on Lying and Deception,’ ‘Augustine’s Own Examples of Lying,’ and ‘The Morality of Lying in St. Augustine.’ On the reception of Augustine’s ideas, see Colish, ‘Rethinking Lying in the Twelfth Century’ and Hermanowicz, ‘Augustine on Lying.’ Both Colish and Hermanowicz rightly note that Augustine treats the problem of lying in several of his other works, often with great flexibility. I focus on On Lying and Against Lying because they are the texts found in the manuscripts of Saint Laurent and Marchiennes.

- In his Retractions, Augustine refers to this work as obscure and difficult, so much so that he ordered it to be taken out of circulation after he wrote his later work on the same subject.

- Hermanowicz, ‘Augustine on Lying,’ 699. Augustine’s Letter 28 to Jerome addresses this issue.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 413.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 414-415: ‘Non emim omnis, qui falsum dicit, mentitur, si credit aut opinatur verum esse quod dicit…Quisquis autem hoc enuntiat quod vel creditum animo vel opinatum tenet, etiamsi falsum sit, non mentitur. Hoc enim debet enuntiationis suae f idei, ut illud per eam proferat, quod animo tenet, et sic habet, ut profert.’ Hermanowicz, ‘Augustine on Lying,’ 704 notes that the primary concern of De mendacio is the ‘ontology’ of lying, that is, in understanding of what a lie consists.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 415: ‘Quapropter ille mentitur, qui aliud habet in animo et aliud verbis vel quibuslibet signif icationibus enuntiat. Unde etiam duplex cor dicitur esse mentientis, id est duplex cogitatio: una rei eius, quam veram esse vel scit vel putat et non profert; altera eius rei, quam pro ista profert sciens falsam esse vel putans. Ex quo fit, ut possit falsum dicere non mentiens, si putat ita esse, ut dicit, quamvis non ita sit; et ut possit verum dicere mentiens, si putat falsum esse et pro vero enuntiat’

- Hermanowicz, ‘Augustine on Lying,’ 708-09. Colish, ‘The Stoic Theory of Verbal Signification,’ 22-35 traces the growing role of intentionality as the defining feature of a lie.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 415: ‘Ex animi enim sui sententia, non ex rerum ipsarum veritate vel falsitate mentiens aut non mentiens iudicandus est’.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 416: ‘Hic enim studio non fallendi mentietur, si mendacium est enuntiare aliquid aliter quam scis esse vel putas.’.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 416: ‘Qui enim verum ideo loquitur, quia sentit sibi non credi, ideo utique verum dicit, ut fallat; scit enim vel existimat propterea falsum putari posse quod dicitur, quoniam ab ipso dicitur’.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 418-19: ‘Aberit igitur omnis temeritatas atque omne mendacium, cum et id, quod verum credendumque cognovimus, cum opus est, enuntiamus et id volumus persuadere, quod enuntiamus’.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 419: ‘Nulla enim definitionum illarum timenda est, cum bene sibi conscius est animus hoc se enuntiare, quod verum esse aut novit aut opinatur aut credit .’.

- It is worth recalling that the Marchiennes copy of De mendacio was bound to a copy of Augustine’s sermon De pastoribus, a point developed in more detail below.

- Denery, The Devil Wins, 116-119.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 426: ‘Cum igitur mentiendo vita aeterna amittatur, numquam pro cuiusquam temporali vita mentiendum est’.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 427: ‘Potest nullam esse pudicitiam corporis, nisi ab integritate animi pendeat: qua disrupta cadat necesse est’.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 444-45.

- Such was Jerome’s argument for why Paul had deliberately lied in his letter to the Galatians. Hermanowicz, ‘Augustine on Lying,’ 699.

- Augustine of Hippo, De mendacio, 429-30: ‘ [non intellegit] deinde ipsius doctrinae auctoritatem intercipi et penitus interrire, si eis, quos ad illam perducere conamur, mendacio nostro persuademus aliquando esse mentiendum. Cum enim doctrina saluataris partim credendis, partim intellegendis rebus constet nec ad ea, quae intellegenda sunt, perveniri possit, nisi prius credenda credantur, quomodo credendum est ei, qui putat aliquando esse mentiendum, ne forte et tunc mentiatur, cum praecipit ut credamus? Unde enim sciri potest, utrum et tunc habeat aliquam causam, sicut ipse putat, officiosi mendacii, existimans falsa narratione hominem territum posse a libidine cohiberi atque hoc modo etiam ad spiritalia se consulere mentiendo arbitretur? Quo genere admisso atque adprobato omnis omnino f idei disciplina subvertitur…atque ita omnis doctrina veritatis aufertur, cedens licentiosissimae falsitati, se mendacio velut of f icioso alicunde penetrandi aperitur locus’.

- The idea of teachers serving as models for conduct is now recognized as central to medieval cultures of learning. See variously Jaeger, Envy of Angels; Münster-Swendsen, ‘The Model of Scholastic Mastery’; and Steckel, Kulturen des Lehrens.

- The text was written specifically with Priscillianists in mind and composed at the behest of Consentinus, who sent Augustine a query about the value of lying for winning heretics to orthodoxy.

- Augustine of Hippo, Contra mendacium, 470: ‘Quomodo igitur mendacio mendacia recte potero persequi?’

- Augustine of Hippo, Contra mendacium, 475: ‘Immo vero cum mendaces mentiendo capimus, mendacia peiora doceamus’.

- Augustine of Hippo, Contra mendacium, 476: ‘Quid autem hora superventura pariat, utrum inde postea liberentur vera dicentibus nobis, qui decepti sunt fallentibus nobis, et utrum audire velint docentem, quem sic experti sunt mentientem, quis noverit certum?’

- Augustine of Hippo, Contra mendacium, 478: ‘Per hoc namque mendacium et nos erimus ex ea parte perversi et ipsi semicorrecti, quandoquidem istuc, quod putant esse pro veritate mentiendum, non in eis corrigimus, quia idem nos didicimus et docemus et f ieri oportere praecipimus, ut ad eos emendandos pervenire possimus’. Colish, ‘The Stoic Theory of Verbal Signification,’ 35 notes that the Contra mendacium does, to a certain extent, contain a greater emphasis on objective truth as a part of lying than does De mendacio in its argument that Catholics who lie are, in fact, worse than heretics who lie, since their lies are both intended to deceive and are objectively untrue.

- Augustine of Hippo, Contra mendacium, 512: ‘Quapropter quando nobis de scripturis sanctis mentiendi proponuntur exempla, aut mendacia non sunt, sed putantur esse, dum non intel-leguntur, aut, si mendacia sunt, imitanda non sunt, quia iusta esse non possunt’.

- Augustine of Hippo, Contra mendacium, 526-27: ‘Aut ergo cavenda mendacia recte agendo aut conf itenda sunt paenitendo; non autem, cum abundent infeliciter vivendo, augenda aunt et docendo’.

- Colish, ‘Rethinking Lying,’ esp. 165-73. Colish, ‘The Stoic Theory of Verbal Signification and the Problem of Lies,’ treats both Augustine and Anselm as heirs to a Stoic tradition of linguistic thought.

- Colish, ‘Rethinking Lying,’ 169-171. See also Hermanowicz, ‘Augustine on Lying,’ 717-727 and Denery, The Devil Wins, 119-135, both of which emphasize the flexible ways in which scholastic thinkers interacted with Augustine’s ideas.

- To date, I haven’t come across any treatises by monastic authors that deal specif ically with the subject of lying, nor even extended sections of any works dealing with the subject.

- Regula Benedicti ed. de Vogüé and Jean Neufville, 470.

- See generally Gehl, ‘Competens Silentium’.

- Regula Benedicti, ed. de Vogüé and Jean Neufville, 470-71: ‘Nam loqui et docere magistrum condecet, tacere et audire discipulum convenit’.

- Bruce, Silence and Sign Language, 13-53, esp. 26-28.

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Oratio pastoralis, 761: ‘Da verum sermonem et rectum et bene sonantem in os meum, quo aedif icentur in fide, spe, et caritate […] in patientia et obedientia.’.

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Speculum caritatis, 60: ‘Simul quidem loqui Ordinis nostri prohibebat auctoritas, sed loquebatur mihi aspectus eius, loquebatur mihi incessus eius, loquebatur mihi ipsum silentium eius’.

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Speculum caritatis: ‘Memini me saepe, cum oculis huc illucque discur-rerem, ad unam eius aspectum tanto pudore perfusum, ut subito intra memetipsum receptus, manu gravitatis omnem illam compescere levitatem, ac me ad me colligens inciperem mecum aliquid utile actitare’.

- Brussels, KBR MS 10260-63, f. 1r.

- Little, ‘Anger in Monastic Curses’.

- Hugh of Saint Victor, De institutione novitiorum, 90: ‘Verbum autem asperum et rixosum a omnino sermonibus disciplinatis secludendum esse per eumdem probatum cum dicitur: “Labia stulti immiscent se rixi et os eius iurgiat provocat”. De verbo etiam mendoso quantum sit cavendum idem ipse insinuat dicens: “Testis falsus non erit impunitus, et qui mendacia loquitur non ef fugiet”’.

- Peter of Celle, Sermo 30: De passione Domini II, 730 : ‘Vide ergo diaetam potionis hujus: silentium, abstinentia, castitas, humilitas, charitas, obedientia, quies mentis, remotio immoderatae joculationis, tranquillitas, pertinent ad observantiam hujus potionis, nec sine his salubriter sumitur, quia non ea purgatur, qui alia lege accipit illam, sed interf icitur’.

- Peter of Celle, Sermo 30: De passione Domini II, 730: Silentio excluduntur mendacia, stulti-loquia, scurrilitates et omne verbum otiosum’.

- Peter of Celle, Tractatus de disciplina claustrali, 101-102.

- Hermanowicz, ‘Augustine on Lying,’ 709, notes that Augustine’s De mendacio suggests that lying required interaction between people via some kind of visible or discernable signs.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae, 3: 48 : ‘Inventa autem occasione loquendi, si de litteris sermo exoritur, vetera proferuntur et nova; volant sententiae, verba resonant ampullosa. Praevenit interrogantem, non quaerenti respondet. Ipse quaerit, ipse solvit, et verba collocutoris imperfecta praecedit’.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae, 48: ‘Esurit et sitit auditores, quibus suas iactitet vanitates, quibus omne quod sentit ef fundat.’.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae: ‘Non ut quempiam aedif icet, sed ut scientiam iactet. Aedificare potest, sed non aedificare intendit. Non curat te docere vel a te doceri ipse quod nescit, sed ut scire sciatur quod scit’.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, De consideratione, 3: 408: ‘Hi sunt qui docuerunt linguas suas loqui mendacium, diserti adversus iustitiam, eruditi pro falsitate. Sapientes sunt ut faciant malum, eloquentes ut impugnent verum. Hi sunt qui instruunt a quibus fuerant instruendi…Nihil ita absque labore manifestam facit veritatem, ut brevis et pura narratio’.

- Anselm of Liège, Gesta episcoporum, 209-210. Vercauteren, ‘Note sure les origins,’ 19-22.

- Cantatorium, 86-89.

- Cantatorium, 98.

- Cantatorium, 155-56, 175-77.

- Cantatorium, 157-64.

- Chronicon Sancti Laurentii, 278.

- Cantatorium, 195- 97.

- Cantatorium, 198.

- Snijders and Vanderputten, ‘From Scandal to Monastic Penance’. My forthcoming article ‘Origen’s Story: Heresy, Book Production, and Monastic Reform at Saint Laurent de Liège’ examines two other important manuscripts from Saint Laurent in this context.

- Snijders and Vanderputten, ‘From Scandal to Monastic Penance’. Cantatorium, 198. For Augustine’s understanding of hypocrisy as lying, see Colish, ‘Rethinking Lying,’ 159 and Hermanowicz, ‘Augustine on Lying,’ 711-714.

- See Ugé, Creating the Monastic Past, 95-141; Snijders, Manuscript Communication, 287-316; Vanderputten and Meijns, ‘Realities of Reformist Leadership’; Vanderputten, Monastic Reform as Process, 135-42; Gesta episcoporum Cameracensium, 460.

- See Vanderputten, ‘Fulcard’s Pigsty’ for analysis and bibliography of Fulcard’s abbacy.

- The most recent scholarly analysis of these events is Vanderputten, ‘A Time of Great Confusion,’ esp. 126-131, for the situation at Marchiennes.

- Gualbert of Marchiennes, Patrocinium, 152-53. Andreas of Marchiennes, Miracula Sanctae Rictrudis, 99-101.

- Vanderputten, ‘A Time of Great Confusion,’ 126; Snijders, Manuscript Communication, 317-331.

- Andreas of Marchiennes, Miracula Sanctae Rictrudis, 110; Vanderputten, ‘A Time of Great Confusion,’ 127.

- Andreas of Marchiennes, Miracula Sanctae Rictrudis, 110.

- Vanderputten, ‘A Time of Great Confusion,’ 127-28.

- Andreas, Miracula Sanctae Rictrudis, 110.

- Andreas, Miracula Sanctae Rictrudis, 111; Vanderputten, ‘A Time of Great Confusion,’ 129-30.

- Vita Hugonis Marchianensis, 348.

- See Černý, ‘Les manuscrits,’ 58-60.

- Peter of Celle, Tractatus de disciplina claustrali, 101-102.

- On the wave of production at Marchiennes, see Černý, ‘Les manuscrits,’ 58-67 and Snijders, Manuscript Communication, 320-340. At Saint Laurent, based on my research, there are around twenty-five surviving manuscripts from the period c. 1100-1120.

- Brussels, KBR MS 9361-67, fols. 90v-96v and 9875-80, fols. 82r-156v. For the latter manuscript, see Van den Gheyn, Catalogue des manuscrits de la Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, 2:309. The former manuscript is not in Van den Gheyn’s catalogue, but Vanderputten and Snijders, ‘From Scandal to Monastic Penance’ of fers a description of its contents.

- Brussels KBR MS 9875-80, fols. 1v-64r, initially misattributed in the manuscript to Isidore, and then corrected to the more common misattribution of Prosper of Aquitaine.

- Brussels, KBR MS 9918-19.

- Brussels, KBR MS 9669-81. See Van den Gheyn, Catalogue des manuscrits, 2: 305-06. This is a dense and complicated manuscript deserving of further examination.

- All of these manuscripts share considerable formal similarities in terms of size, layout, and decoration.

- Fols. 39v-40r.

- Primarily the material in Augustine of Hippo, Contra mendacium, 486-514.

- Vanderputten, ‘A Time of Great Confusion,’ 112-113.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Epistola 339, par. 8, ed. Leclercq and Rochais, 279-80: ‘Marcianenses monachi venerunt ad vos in spiritu mendacii et spiritu erroris, adversus Dominum et adversus christum eius. Verbum iniquum constituerunt adversus Atrebatensem episcopum, cuius conversationis et vitae bonus odor fuit hactenus in omni loco. Qui sunt isti, qui ut canes mordent, qui dicunt bonum malum, qui ponunt lucem tenebras? Qui sunt isti, qui contra legem maledicunt surdo et coram caeco ponunt of fendiculum’.

- Snijders, Manuscript Communication, 324.

- Douai BMDV MSS 250, 258, 281, 271, 275, 251, and 277.

- Douai BMDV MSS 265, 267, and 270.

- Dehaisnes, Catalogue général des manuscrits, vol. 6. Douai, 142-43.

- Dehaisnes, Catalogue général des manuscrits, vol. 6. Douai 139.

- Dehaisnes, Catalogue général des manuscrits, vol. 6. Douai 140.