Systemic plunder and lawlessness.

By Dr. Vahram Abadjian

International Affairs Analyst

Coalition for Local Self-Government of the Kyrgyz Republic

Abstract

The article ‘Kakistocracy or The true story of what happened in the post-Soviet area’ argues that the countries, emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Empire, chose three distinct models of development: the Baltic model, when Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania joined the Euro-Atlantic security structures; the Belarusian model, when the country opted for an authoritarian rule with a possible transition from the communist totalitarianism to an open society; and the Russian model, when under the slogans of democracy and market economy a new type of regime was established in Russia and a number of post-Soviet countries.

To characterize this new type of regime the definition of ‘kakistocracy’ has been introduced, which means a merger between the state structures and the oligarchic elements as a result of the systematic plunder of national assets and establishment of a rule of lawlessness and illegal usurpation of power under the slogans of democracy and market economy.

Furthermore, the split of the CiS and the formation of two groups of countries, respectively the GUAM and the CSTO, have been considered from the viewpoint of their different strategic goals and orientations.

A section is devoted to the cardinal differences between the strategic visions of Yeltsin and Putin. The latter’s policy can be formulated as the Putin’s doctrine aimed at restoring Russia’s influence through centralization of power, internally, and demonstration of military force and energetic blackmail, externally. The kakistocratic regimes lead to a political and socio-economic collapse, triggering popular unrest. This exactly was the reason of the ‘orange’ revolutions, which in most of the cases are the only way to topple kakistocratcy.

In conclusion, it is suggested that the other way of getting rid of kakistocracy would be a cardinal change in Russia’s policy. While the strategic goal of the country should remain restoring its international influence and authority, the means should shift from heavily relying on military power and energetic resources toward focusing on the Russian spiritual values and potential for facing new threats and challenges to international peace and security.

Introduction

After almost two decades of the Soviet Union’s disintegration a lot remains to be clarified on what in reality took place in the former Soviet republics, what kind of transformation did they undergo and what are their development trends. This subject seems to be important for a number of reasons, which have both internal and external implications. To put it succinctly, it is crucial that a considerable part of the planet’s population could develop its political, socio-economic and cultural potential, internally, and contribute to the progress of mankind and international peace and security, externally.

The difficulty of in-depth understanding of the processes and trends in the post-Soviet area stems from the abundance of misinterpretations and false targets due to the euphoria after the collapse of the Soviet empire which, at first sight, heralded the end of the Cold War and the beginning of a new era. It was exactly in the late 1980s and the early 1990s that Francis Fukuyama’s “The End of History and the Last Men”, predicting that history should definitely choose liberal democracy as humanity’s ultimate achievement thus precluding any qualitatively new historic development, became and still remains a bestseller (Francis Fukuyama, 1992). It is exactly in 1990 that the Conference (at present – Organization) on Security and Co-operation in Europe adopted the Charter of Paris for a New Europe (1990), where the Heads of State or Government of the Conference solemnly proclaimed a ‘new era of Democracy, Peace and Unity’.

Indeed, in early 1990s the ex-Soviet countries were admitted to the United Nations,1 became OSCE participating States and nowadays all of them, save Belarus and the Central Asian countries, are members of the Council of Europe, which per se could have been a clear indicator of their commitment to observe human rights and fundamental freedoms.

This accession to the international organizations and acceptance of the international instruments and laws went in parallel with internal changes, which seemed to bring about the establishment of democratic structures and market economy, thus ostensibly materializing the authoritative predictions of political scientists and the enthusiastic statements of politicians.

Unfortunately, over the past twenty years the historic reality proved to be a different one. The bypassing of the UN Security Council in some critical decision-making instances, the deep crisis of the OSCE, the transformation of the Council of Europe from an exclusive into an inclusive organization, where the behaviour of certain newly admitted members has become subject to periodic discussions and permanent concern – all these facts reflect the deeper tendencies of a new divide and discord between the West and the East and the international community’s obvious failure to unite its resources and political will vis-à-vis the new threats and challenges to international peace and security.

While discussing the causes of this divide and considering the possible ways out of such a situation should become subject to a comprehensive and detailed analysis, this article aims at concentrating on the real situation in the post-Soviet countries and its impact on the international developments. In order to achieve this objective the article will consider the different groups of states that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union, in particular, the CIS countries and the fault lines between them. Furthermore, an attempt will be done to formulate a definition meant to reveal the genuine nature of the ruling regimes in the bulk of the post-Soviet countries. It is all the more important since the nature of power in those countries triggered the so controversial ‘orange revolutions’, and will most probably trigger new ones jeopardizing the security environment not only internally, but regionally and even at a larger scale.

Understanding the real nature of the regimes that dominate in most of the post-Soviet countries is necessary for the politicians and the civil society both in those countries and internationally, because it is not possible to find a remedy without knowing the root causes of a threat, which is covered with the veil of good intentions but has an enormous potential to spread over stealthily and imperceptibly.

Three Models of the Post-Soviet Countries’ Development

Overview

Homogeneous as they might seem, the Soviet republics had different historic and cultural backgrounds, as well as different levels of socio-economic and cultural development. True, the communist system, its ideology, structures, values were omnipresent in the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, one could not compare the Baltic countries with the Central Asian ones, or the Slavic republics with the Southern Caucasus. This stands true not only with regard to their level of development or cultural differences, but also from the point of view of the degree of their acceptance of the communist regime and their attitude toward the country, whose citizens all of them were.

Whoever has lived in the USSR knows that, for instance, the Baltic countries have never been “truly” Soviet and were considered as being a kind of “abroad”. On the other hand, the Central Asian republics really owed a lot to Russia and the communists, whose rule had been instrumental in bringing the quasi-feudal societies there closer to the civilized standards in education, healthcare, equal treatment of women, etc.

While the Baltic republics have never accepted their annexation by the USSR in the wake of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the others had found a kind of modus vivendi, thus accommodating their own not very ambitious agendas under the aegis of one of the two superpowers of the time.

If not entirely, these differences in perceptions and level of progress played a significant role in the determination of the post-Soviet countries’ strategic directions in the context of their historic choice after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Among other factors one could stress the geopolitical specifics of separately taken countries, as well as the individual qualities of the politicians who came to power on the wave of the historic events of the late 1980s and the early 1990s.

The strategic task of any state, in particular, the one emerged on the ruins of an empire can be described by a very simple formula: security and well-being. The newly independent post-Soviet countries, which after the disintegration of the Soviet Union lost a powerful security umbrella and an acceptable level of well-being, found themselves in front of a historic challenge, whose gravity became obvious as soon as the new political forces took up the reins of leadership. Whatever different the options for tackling the unprecedented challenge might be, one can argue that the former Soviet republics, notwithstanding the nuances and specifics, opted for three respective models of development: the Baltic model, the Belarusian model and the model of the remaining countries headed by Russia. At least a brief analysis will be important to realize the gist of these three different models, all the more so since each of them had its own characteristics and logic, which produced a long-lasting effect on the domestic and external politics of the countries in question.

The Baltic Model

As compared to the other post-Soviet countries the problems of security and well-being could be solved in the most successful way by the Baltic countries. There is little wonder to it.

Apart from the fact that the Baltic countries had joined the Soviet Union later than the other constituent republics and that they had always been considered as being “abroad”, one should also single out two prevailing circumstances that have played a decisive role in their success story. First, the Baltic countries have always been part of the Western, purely European civilization, and they did not need any significant transition period in order for them to accept, adopt and absorb democratic values. Second, geopolitically, the Baltic countries are closer to the Scandinavian countries, and this Nordic vicinity could not play but a role of a catalyst in their accelerated inclusion in the Western European political and security realm.

Indeed, in 2004 all three countries of the region: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania became European Union and NATO member states. More important, perhaps, is the fact that unlike a number of other countries, which were included in these organizations for mainly geo-strategic and political reasons, the Baltic countries really had achieved or potentially could achieve in relatively short historic period political and socio-economic stability and progress based on Western standards.

True, the Soviet economic system, the existence of communist nomenklatura, the attempts of Russia to play on the patriotic feelings of the considerable Russian minorities in Latvia and Estonia could at first sight significantly hurdle the Baltic countries’ development and rapprochement with the West. Nevertheless, these hurdles were relatively easily overcome for the above-mentioned major reasons: civilizational and geopolitical vicinity to the Scandinavian countries and through them to the Western Europe.

Thus, the Baltic model of post-Soviet development was characterized by a relatively smooth and painless transition from the communist totalitarianism to a Western type democratic rule. Nowadays, these countries are fully integrated in the Western European structures, and from the point of view of further analysis, at least, in the context of this article they do not represent any considerable interest. In turn, what happened in the other parts of the former Soviet Union is much more intriguing and requiring non-standard approaches in order to be tackled and understood.

The Belarusian Model

The events in Belarus developed according to a totally different scenario. They are inalienably linked to President Lukashenko, who has been ruling the country since 1994. A strict hierarchy of state structures, dubbed ‘the presidential vertical’ and well defined priorities both in domestic and foreign policy are the main characteristics of his rule. In other words, Lukashenko’s leadership is a combination, as strange as it may seem, of iron fist and consistent efforts to protect the Belarusian national interests.

The country and its leader have virtually been demonized, and for people in Austria, Germany or Spain, let alone America, the Belarusian regime is nothing else but ‘Europe’s last dictatorship’. This label along with the ‘rogue government’ or – the jewel in the crown – ‘Jurassic Park of authoritarianism in the heart of a democratizing Europe’2 has become a kind of fairy tale roving theme, which wanders through articles and statements, without giving any meaningful explanation of what is really going on in the country.

In reality, the Belarusian model of development represents quite a unique example. Unlike the other post-Soviet countries guided by Russia, whose development model is yet to be considered, Lukashenko could avoid plundering of the country by a handful of oligarchs. He was able to preserve the country’s national asset and secure real prerequisites for a transition from the Soviet totalitarianism to an open society through authoritarianism. The Belarusian example demonstrates with all evidence that after the collapse of the Soviet Union it was not possible to build a democratic society and market economy just proclaiming good intentions and devotion to democratic ideals. There was really a need of an iron fist, which would prevent selling the country both internally and externally.3

This is not to say that the regime in Belarus is impeccable. Examples of the authorities’ restrictive policies toward a number of fundamental human rights, in particular, freedom of expression and assembly, as well as their obvious reluctance to promote independent civil society are more than enough. However, what matters in the context of this article is the overall algorithm of the Belarusian development after its independence. Belarus’ real problem is not that it is a dictatorship or a country, where an authoritarian regime has been established. Belarus’ real problem is whether or not the above-mentioned algorithm of transformation from Communist totalitarianism to authoritarianism and from authoritarianism to an open democratic society will ever become reality. While internally, the logic of history and the trends of development should sooner or later bring about cardinal political and economic reforms, lots depend on the external setting.

Indeed, the geo-political situation of Belarus is not an easy one. It lies between two great powers – the European Union and the Russian Federation. Each of them aims at including the country into the sphere of its influence, and the outcome of Belarus’ model of development will heavily depend on which of these two powers will win this tug-of-war and whether or not the Belarusian leader, be it Lukashenko or anyone else, will be wise and flexible enough to further protect the country’s national interests, preserve and augment its national asset and play a worthy role in international affairs.

Whereas the answers to these questions should be sought, perhaps, in not so remote future, here it would be important to sum up the characteristics of the Belarusian model of development. The bottom line of the Belarusian model is that after the collapse of the Soviet Union an authoritarian regime was established in Belarus, which helped avoid plundering the country under the guise of privatization and market-oriented economy. Thus, a powerful barrier was put against the formation of a cleptocratic pseudo-elite4 who having recourse to beautiful slogans on democracy, human rights and fundamental freedoms, could and would have established a regime of their personal power and personal interests.

True, the above-mentioned Belarusian dilemma of development is far from being resolved, and most probably the country will face further challenges both internally and externally. Nevertheless, if the positive trends prevail, Belarus will have much better chances to become a genuine European state than many post-Soviet countries, whose model of development can hardly be characterized by definitions taken from the usual political lexicon of modern times.

The Russian Model

While the Baltic countries’ and Belarus’ models of development are based on strategically clear and structurally logical foundations – Western type democracy regime in the case of the former and authoritarian regime in the case of the latter – the model of development of Russia and the remaining states, emerged after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, is hard to characterize within the framework of the existing terms and definitions.

At first sight, it seems that an analyst should encounter no difficulty when tackling the situation in those countries. Indeed, Russia, Ukraine, a number of countries in the Southern Caucasus and Central Asia proclaimed after the independence their determination and good will to embark upon political and socio-economic reforms to promote democratic values and achieve prosperous life for their peoples. The first president of independent Russia, Boris Yeltsin, who heavily relied on a cohort of young and ambitious politicians, launched a thesis supported by the leaders of the bulk of the newly independent countries on the transition period.5 According to this thesis such a period was necessary to transform the Soviet totalitarian system into real democracy through privatization of enterprises, banks, infrastructure and other branches of economy, encouragement of private business, creation of appropriate environment for free media, conduct of free and fair elections, establishment of a multi party system and the like.

Nevertheless, life brought about quite a different scenario. In a rather short span after the independence it became evident that the newly emerged countries had been deviating further and further from the proclaimed goals and strategic targets aimed at implementing real democratic reforms in the political and socio-economic spheres. In particular, the privatization ended up with appropriation of the major enterprises and other economically significant assets by a handful of people dubbed “oligarchs”. Those in power up until now justify the oligarchs’ appearance by the rules of market economy, often referring to the medieval Europe’s primary accumulation of capital, or hinting that free market quite naturally is regulated by the jungle law. One could even agree with such argumentations, absurd as they might be, if not the highly doubtful circumstances, in which the whole story of privatization in Russia and some other post-Soviet countries has unfolded. It is obvious that those undertakings had nothing to do with real market economy and catered to the interests of a few members of society versus the interests of the people and the state.

It goes without saying that this upheaval in the sphere of economy could not occur without the support from the political quarters. More than that, the political leadership did not simply condone but took active part in the shameful appropriation of popular assets. Proclaiming a ‘transition period’ turned out to be a signal of complacency and impunity.

Thus, under the slogans of democracy, market economy, individual rights and freedoms a few people, sometimes with suspicious past, appropriated the national asset of a huge country. The merger of the oligarchs with the political leadership, when each of the two parts of the hybrid could not exist without the other part’s support and co-operation, led to a new and unexpected situation, which influenced the whole spectrum of political and socio-economic life in Russia and a number of other post-Soviet countries. Trying to understand how this could be possible leads us to the following conclusion.

The tragedy of Russia and the bulk of the other post-Soviet countries consists in the fact that having destroyed the old structures of power, having rejected the obsolete principles of political and economic governance, having gotten rid of the tools of control over the population but also over the nomenklatura, including its highest representatives, the new leadership could not or did not want to create new structures of truly democratic power and governance, could not or did not want to replace the totalitarian methods of control, which secured responsibility through fear of being persecuted, with effective and efficient methods of control and responsibility through democratic mechanisms.

The outcome is well known: devaluation of the notion itself of democracy and hatred by a considerable part of population of anything associated with the democratic reforms in the politics and economy; nostalgia of many people among the old and middle generation for the old good Soviet times; overwhelming mercantilism with its idée fix of making quick and easy money; thriving corruption, protectionism and impunity.

At this juncture, a question may arise: what is then the nature of power of those leaders, and what kind of regime has been established in those countries?

Clearly, notwithstanding the slogans and the proclaimed goals, this was not a democracy, because the power was taken not by the people but by the state-oligarchic rulers. This was not a dictatorship or authoritarianism in the Belarusian sense, because authoritarianism establishes clear and strict rules imposing responsibility of any employee or government structures’ member before his/her supervisor and before the smoothly functioning structures of state control.

The unusual and unprecedented situation created as a result of a merger between the ruling political forces and the oligarchic structures brings about the necessity of non-standard definition to characterize the real and not desirable changes in Russia and a number of countries with a similar model of development.

The gist of the regime established as a result of those changes could be characterized by the ancient Greek world “kakistocracy” – Government by the worst citizens. In the context of this article this phenomenon may be defined in the following way.

Kakistocracy is a political and socio-economic regime based on plundering of the state’s and the people’s asset and property through a merger between the political leadership and the criminal oligarchic structures under the guise of the democratization of the society, introduction of market relations in economy, the rule of law and priority of human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The major features of kakistocracy are: usurpation of power through unfair and falsified elections; growing polarization of the society, impoverishment of the bulk of population and enrichment of a handful of nouveaux riches; selling out to the foreign capital the economic and other assets based on clan interests; thriving corruption and the rule of lawlessness.

Of course, the expression “Government by the worst” should not be understood in a way that the political leaders or the representatives of the oligarchic circles are bad guys and bastards. Clearly, this is not the case. Often one can happen among them very knowledgeable, well-educated, polite persons, many of them, perhaps, sincerely considering serving the homeland as their supreme objective. The thing is that whatever and however they do turns into their profit and against the interests of the nation. The reason of such state of affairs is that the very essence, the very nature of power remains intact. It does not stem from the interests of larger segments of the population but is oriented toward a narrow circle of persons. In order to break this vicious circle there is a need of extraordinary and non-standard measures. This matter will be analyzed in a relevant section of this article.

Summing up, it should be emphasized that kakistocracy is the basic element of Russia’s and some other newly independent countries’ post-Soviet model of development. Kakistocracy is the key to understanding the root causes which have shaped and will further shape the behaviour of those countries’ political leadership and their decision-making fraught with serious consequences both externally and internally.

The Split of the CIS: Centrifugal and Centripetal Forces

Overview

The analysis of the above-mentioned three distinct models of development is only a first necessary step toward understanding the real situation in the post-Soviet countries. There is a no less important subject for analysis all the more complicated since it has triggered different, sometimes conflicting interpretations. This subject is the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Already the very reason of the CIS formation has become a matter of misinterpretations and opposite views. According to one opinion the CIS was created in order to insure a civilized divorce of the countries, which used to be part of a single state formation. According to another opinion the CIS was established to restore the broken political, economic and other ties between those countries with the prospect of reunification under the umbrella of a new super power at a qualitatively new level.

The truth, however, consists in the fact that the CIS has simply ceased its existence already in the middle of the 1990s as a result of an irreversible split. The fault line lies between the centrifugal and centripetal forces toward Moscow.

Centrifugal Forces

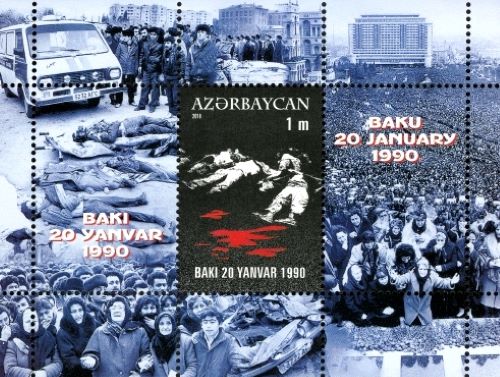

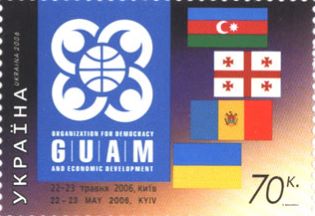

It is exactly in mid-1990s that a new political alliance comprising a number of former Soviet countries (GUAM: Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova) was shaped. Formally, this new alliance was established in October 1997 as a Consultative Forum. Thereafter, GUAM witnessed a certain evolution, when the Consultative Forum was transformed into a Union (June 2001) followed by the creation of the Organization for Democracy and Economic Development (May 2006) with a Council and a Secretariat based in Kiev. In 2004, the GUAM Parliamentary Assembly was established.

According to GUAM Charter the purpose of the Organization is the promotion of democratic values, the rule of law and human rights, insuring sustainable development, enhancing international and regional security and stability, etc.6 True, these proclaimed goals reflected the new Organization’s good will and commitment to internationally recognized values. However, GUAM was shaped not only for the sake of joining its members’ efforts to achieve those goals. Two major incentives have led to GUAM formation and activities. Both can be detected with naked eye. They lie on the surface and reflect what is beneath.

All four GUAM states include national minority territorial units which adamantly strive for their independence. In the time of GUAM inception in Georgia these were Abkhazia, Ajaria and South Ossetia; in Azerbaijan – the Upper Karabakh; in Moldova – the Transdniestrian region and in Ukraine – the Crimea. Although since the mid-1990s in some of these areas considerable developments have occurred, it is so far too early to speak of any cardinal change or conflict settlement. It goes without saying that the common nature of danger that the central governments faced led to a commonality of aims and interests and to a need for unifying their efforts in the hope that together the problem could be overcome easier and faster.

Other communality is GUAM members’ reorientation toward new security arrangements and new strategic partners. In case of Ukraine and Georgia this is more than obvious, and the question of their membership in NATO, notwithstanding considerable difficulties, seems to be a matter of time. In case of Moldova and Azerbaijan the situation is less evident. Nevertheless, at the end of the day their western orientation should prevail, especially, given the attractive force of two countries belonging to the Euro-Atlantic community – Romania and Turkey both of them having traditional links with, respectively, Moldova and Azerbaijan.

These two circumstances have objectively played a decisive role in GUAM drifting away from Russia. Indeed, the break-away unrecognized territorial units heavily rely on Russia in their quest for independence. In its turn, Russia tries to use these expectations as a trump card to advance its strategic interests and prevent GUAM from definitively getting out of its political influence. The August 2008 events in the South Ossetia are perhaps the best illustration to this.

It is natural that the GUAM countries, if the trend of rapprochement with the Euro-Atlantic security arrangements is to prevail, must accept the rules of the game and make decisive movement toward a real democratization of their internal life. To maximize their chances of acceptance into the NATO they have to think about making serious and not faked reforms to establish the principle of separation of powers, promote the rule of law and human rights and translate solemn declarations about democracy into real life. In particular, the “orange revolutions” in Georgia and Ukraine took place, on the one hand, because of a total fiasco of the kakistocratic regimes and, on the other hand, because of the aspiration of the new political leaders to stick to European and American orientation and scale of values.

On 18 August 2009, Georgia withdrew from the CIS. Is this the beginning of a formal disintegration, will the other GUAM members follow suit, what will be the impact of Georgia’s decision on the overall trends of development in the post-Soviet countries? Only further unfolding of events is able to answer these questions. At this stage, one can stress that this first formal withdrawal is an additional clear demonstration of the split of the former Soviet countries into two distinct groups. We have touched upon the centrifugal group. It is now time to see what the actual state of things is when it comes to the other group centripetal to Moscow.

Centripetal Forces

Compared to the centrifugal group, the second group of countries has adopted a diametrically different policy vis-à-vis Russia. The members of this group – Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan – have opted for security arrangements under the auspices of Russia and, consequently, have found themselves in the sphere of Russian influence not only from the security but also from political and economic viewpoints. The attribution of these countries to the centripetal group is not based on their belonging to the CIS. Here, the basic principle is rather their membership to the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which tends to become a well-structured and potentially strong politico-military organization and as such should be taken into serous consideration.

It goes without saying that the above-mentioned countries are not homogenous and have sometimes differing political agenda. Armenia has adopted foreign policy based on “complementarity”, to put it simply, equally close relations with Russia and the West; Belarus is subject of influence from both the West and the East, and it is not known whether or not the tug-of-war between them will ever yield a result; the Central Asian countries are also subject to different influences, having in mind, apart from Russia, China and serious security threats coming from Afghanistan and northwest of Pakistan. Notwithstanding these specifics of separately taken CSTO members, there is one prevailing circumstance uniting them around a common goal: the strategic orientation toward enhancing politico-security alliance headed by Russia.

The Charter of the CSTO, adopted in 2002, clearly states that the purpose of the Organization is to promote peace, strengthen international and regional security and stability, and ensure the collective defense of the independence, the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the member states. Without casting any doubt over these intentions, it also should be stressed that, like GUAM, the CSTO apart from these proclaimed goals has a hidden agenda. The American analyst, Major (P) John A. Mowchan, 2009, has clearly pointed to this circumstance, stressing that: ‘[t]he militarization of the CSTO alliance and its transformation into a credible security organization could bolster the Kremlin’s ability to limit U.S. and Western influence in Eurasia. It could also allow Russia an enhanced ability to increase its control over former Soviet-controlled states and re-create an alliance similar to the Warsaw Pact”.

At this very juncture, this conclusion may seem to be premature. However, it goes in line with the recently adopted Russian National Security Strategy and reflects the strategic approaches of the post-Yeltsin Russian leadership in terms of security and foreign policy. Certainly, it is not possible to predict whether the Russian strategic domination will materialize or the existing differences will make the CSTO fall apart, as was the case with the CIS.

From this article’s angle it is, perhaps, more important to point to another similarity. All CSTO members, except Belarus, represent kakistocratic regimes. Once again, this is a general bottom line and in no way does it deny the existing differences between them. However, the kakistocratic nature of these regimes has determined the major directions of the relevant countries’ internal and external policy and serves as a constant generator of their behaviour and comportment. As such, the logic of developments and the events that have occurred in the centripetal countries represent a mirror reflection of what has happened in Russia – the founding mother of kakistocracy.

Putin’s Doctrine and Cold War II

Russia’s post-Soviet history can be divided into two distinct periods: the 1990s – Yeltsin’s rule and the 2000s – Putin’s rule. President Boris Yeltsin was a statesman, who played a major historic role in Russia’s post-Soviet developments. His rule was contradictory and controversial. It also can be roughly divided into two parts: the destruction of the communist ideology, the communist party and the communist empire in the late 1980s and early 1990s and laying the ground of kakistocracy thereafter by conducting reforms, whose final outcome was creation and strengthening of criminal oligarchic pseudo-elite and its merger with the political leadership. It is hard to say which one of these accomplishments will serve as a criterion for assessing Yeltsin’s contribution to the world history in, say, 50 years or so. In any case, Yeltsin’s example clearly demonstrates that in times of historic turmoil the role of the leader becomes decisive in shaping a given country’s future.

As the logic and the trends of developments of Russia in the 1990s heavily depended on the figure of its first president, so the trends of the country’s developments in the first decade of the 21st century were shaped under the strategic leadership of Russia’s second president Vladimir Putin. It might be useful to consider the main differences between these two periods and their impact on the international relations.

When it comes to the differences with regard to internal policy, it should be underlined that from the point of view of the nature of power Russia has not changed since its independence. Both Yeltsin’s and Putin’s regimes are typical kakistocracies insofar they pursue the political and economic interests of those in and around the power. Putin got rid of some oligarchs and tried to make a new order. But this led to a mere replacement of some old oligarchs with new ones, while the system itself remained intact. As to making order, this was and has been done through the centralization of state institutions, the curtailing of the political life’s diversity and the strengthening of the law enforcement structures with the straightforward approach that order can be and should be re-established by centralized power and force.

This same straightforward approach is typical also for Russia’s foreign political strategy. Unlike Yeltsin, who declared during the turmoil triggered by the collapse of the USSR that its constituent republics should take as much sovereignty as they could, thus revealing a broadmindedness of a statesman, Putin’s Russia in its relations with the “near and far abroad”7 heavily relies on politico-military component of security and believes that richness in oil and gas is a privilege affording the country to dictate its rules whomsoever and howsoever.

This approach is the cornerstone of modern Russia’s domestic and external policy and as such has been reflected in the country’s most important and authoritative documents. In 2003, the “Energy Strategy of Russia for the period until 2020” was adopted, which from the outset stated the following: “Russia possesses considerable deposits of energetic resources and a powerful fuel and energy complex, which represents a basis of economic development, an instrument of carrying out internal and external policy. The country’s role in the word energetic markets defines to a great extent its geo-political influence.”

The same strategic view is reflected in the “National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation until 2020”, promulgated by President Medvedev on 12 May 2009. Chapter 9 of the document states: “Transition from the block confrontation to the principles of multi-vector diplomacy, as well as Russia’s resource potential and the pragmatic policy of using it have broadened the possibilities of the Russian Federation for enhancing its influence in the world”. Another part of the document concerning the national defense obviously stems from the old Cold War times’ rhetoric. It states: “The threats to the military security are: the policy of a number of leading foreign countries aimed at obtaining overwhelming superiority in the military sphere, first of all in strategic nuclear forces….” (Under Chapter IV Enhancing National Security Part 1. National Defense).

These principles, enshrined in the Russian cornerstone documents, have been reiterated on many occasions by presidents Putin and Medvedev, respectively. Thus, shortly before handing over his office to Medvedev in his speech on the country’s national strategy in February 2008, Vladimir Putin (2008) underlined that “[t]he only alternative of deterring NATO’s expansion and other hostile politico-military moves toward Russia is developing the production of new types of arms not yielding by their quantitative characteristics those at the disposal of other states and in certain cases even surpassing them.”8

In his latest Address to the Federal Assembly of 12 November 2009, President Medvedev (2009) clearly stated that “[o]ur foreign policy must be exclusively pragmatic”. Although throughout his Address Medvedev has emphasized that the key word of his politics was “modernization of Russia”, in reality, the key world of the Russian politics after the year 2000 is “pragmatism”: pure pragmatism, deprived of any ideological basis or any more or less considerable idea, able to lay the ground for elaborating serious strategic approaches of a country, which pretends to be a superpower.

To conclude this series of quotations from the current Russian leadership let us refer to Medvedev’s article entitled “Go Russia!”(http://eng.kremlin.ru/speeches/2009/09/10/1534_type104017_221527.shtml). All in all, the article leaves a mixed impression. It is highly critical and singles out a number of acute problems and threats that may have a long-lasting and highly negative influence on the country’s development. These are: “inefficient economy, semi-Soviet social sphere, negative demographic trends, and unstable Caucasus” (p.2). Furthermore, Medvedev strongly criticizes corruption, paternalistic attitudes and a number of other scourges preventing Russia from progress and modernization. However, the article does not contain any sound analysis of the root causes of all these negative elements. It does not reflect the very essence of the developments in the country after its independence. Therefore, the set of recommendations on solving those problems is of a rather technical nature void of strategic vision. Medvedev’s vision is based rather on common sense, his proposals for Russia’s modernization in the field of economy, social sphere, human rights and the rule of law, democratic governance, etc., cannot but be praised. The problem is that they are of little relevance to today’s country, and the Utopian picture of a prosperous, strong, just and democratic Russia, so emotionally depicted by Medvedev, in fact, does not inspire, because it lacks the most important thing: a spiritual concept of Russian national revival, without which all reforms at technical level are doomed to be just a next failure, damaging the Russian national dignity and hampering its huge civilizational potential to promote international peace and progress.

Taking into thorough consideration the developments in Russia since 2000s, the strategic documents adopted by the country’s leadership in the field of national, military, energetic security, the Russian leaders’ statements, as well as their practical steps undertaken in both domestic and external policy, it should be concluded that we are dealing with a well-structured and well-elaborated strategy. This strategy of the modern Russia’s leadership, perhaps, can be better characterized, if we place it into the format of a doctrine. Since the initiator and the adamant implementer of the doctrine is Putin, whereas Medvedev has only followed suit, it would be appropriate to say that we are dealing with the Putin’s doctrine. To put it succinctly, the Putin’s doctrine aims at centralization of power and uniformity of political life, internally, and at restoring Russia’s superpower status through heavy reliance on military force and energetic resources, externally. It should be added that Russia’s aspiration to restore its superpower status is quite natural and understandable. What raises concern, is the way and the methods that the country’s leadership has adopted to achieve it. While in the last part of this article an attempt will be done to demonstrate how this aim could be achieved in a civilized way, here it is appropriate to concentrate on another matter of concern.

This matter of concern is the real threat of relapse into renewed tough confrontation between the West and the East or recurrence of the Cold War under new historic circumstances and conditions. Indeed, the euphoria, mentioned in this article’s introductory part, roughly speaking lasted a decade: from 1991 to 2001. Two historic events frame this decade – the collapse of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the Twin Towers. This decade was dominated by a unipolar world order under the US supremacy. The American ideas of liberal democracy were especially predominant at that time, and many believed that the “universal democratic revolution”, at least in the Euro-Atlantic area, was coming to a triumphal completion. The destruction of the “evil empire” seemed to be adequate to the eradication of the “evil” as such. Nevertheless, 11/9 clearly demonstrated the end of the American supremacy, insofar a country allowing such a tragic blow cannot be considered by definition as being the only superpower. Exactly at this juncture the first symptoms of Cold War II have appeared.

One of the most convincing examples of the above-mentioned danger of relapse into tough confrontation is the history of the evolution of the OSCE. Created in the middle of 1970s as a diplomatic platform for negotiations between the West and the East, it served to re-confirm the Euro-Atlantic security arrangements as set forth by the Yalta agreements of 1945. In early 1990s after the fall of the Berlin wall the OSCE adopted a number of documents in the firm conviction that Yalta had remained in the past and that a new era of democracy, peace and unity would now determine Europe’s security and progress. Nevertheless, as of early 2000s the Organization found itself in a deep crisis due to the newly emerged dividing lines between the considerably broadened West and the considerably shrunken East.

Russia and its allies, namely, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, have on many occasions made joint statements at the OSCE’s permanent Council’s and other structures’ sessions, appealing upon the other participating States to reform the Organization, to relinquish the practice of double standards, to restore its role as the universal mechanism of pan-European security. However, there is little wonder that those appeals have remained the voice of one crying in the wilderness. The responsibility for European security architecture, speaking of Europe as such, has been taken over by the NATO and the European Union, and there cannot be any backward movement to the middle of the 1970s, to the status quo ante, when the OSCE was established. This is not to say that the Organization’s crisis has been triggered exclusively by Russia and its allies. Western Europe has fully taken profit from the end of the Cold War in its favour, sometimes subduing the logic and the pace of historic development to the expediency of military and geo-political enlargement. Whatsoever the reasons might be, this enlargement was due first and foremost to the huge political, economic and cultural attractiveness of the European Union versus the Russian heavy reliance on imposing itself by force and energetic blackmail.

The existence of dividing lines in the Euro-Atlantic area of security and the need of its abolition have been reflected in the OSCE documents adopted at highest levels. The freshest example is the Ministerial Declaration of the 17th OSCE Ministerial Council which took place on 1-2 December 2009 in Athens. The Ministers of Foreign Affairs of 56 OSCE participating States have pointed out that: “The vision of a free, democratic and more integrated OSCE area, from Vancouver to Vladivostok, free of dividing lines and zones with different levels of security remains a common goal, which we are determined to reach”. Furthermore: “Our highest priority remains to re-establish our trust and confidence, as well as to recapture the sense of common purpose that brought together our predecessors in Helsinki almost 35 years ago”.9

Back to square one: the OSCE has spent almost 35 years to realize that its highest priority “remains to recapture the sense of common purpose”. It is beyond the subject of this article to further concentrate on the OSCE and the ways that could re-establish trust and confidence among its participating States. Here it should be noted time and again that the Organization’s divide and despaired efforts to overcome the confrontation eloquently speak of the real possibility of engaging into another Cold War with all its damaging consequences to say the least.

While overcoming such a situation will require joint efforts and solidarity, it is first and foremost Russia and its allies that should adapt themselves to the new realities, whatever bitter they can be: the reality of the collapse of the communist system and communist values, the reality of the Western supremacy and enlargement, the reality of huge difficulties of internal development due to the hurdles imposed by the kakistocratic regime. But with the passage of time it becomes clearer and clearer that kakistocracy is so deeply embedded in the system of rule of the above-mentioned countries that it can hardly be overthrown without decisive and coercive actions. The “orange” or “colour revolutions” occurred in a number of post-Soviet countries are the best testimony to this affirmation, however strange and unacceptable it may seem at first sight.

Orange Revolutions

When on 23 November 2003 President Shevardnadze of Georgia resigned under the pressure of popular unrest and indignation, no one could suppose that this same scenario would be soon repeated in Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan. The frequency and similarity of the situations of upheaval triggered by crisis of power and popular demonstrations in these and some other post-Soviet countries allowed to draw a common denominator by dubbing such situations as “orange” or “colour” revolutions. They have been commented and interpreted from different, sometimes, diametrically opposite viewpoints, ranging from praise and admiration to condemnation and ill-disguised hatred. Those who are positive refer to the triumph of democracy and the will of people vis-à-vis corrupt leaders and regimes. Those who are negative believe that these revolutions were nothing else but an unconstitutional attempt to change the regime, masterminded and financed from abroad, mostly from the United States.

The book “Orange Nets: from Belgrade to Bishkek”, which contains a number of articles on the “colourful” events in the post-Soviet countries, is perhaps the most outspoken evidence of harshest criticism. The contributors concentrate on the events in Yugoslavia, Georgia, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, as well as on the financial and operational instruments activated by the “foreign powers” in order to achieve a regime change in those countries. Their conclusion is unequivocal and is best expressed by the editor, Natalia Narochnitskaya, a well-known Russian political scientist and practitioner, in her introduction to the book. She states that a series of “orange” revolutions some twenty years ago would be called coup-d’États (p.5).

To support this “conspiracy theory”, the authors refer to foreign embassies’ and foundations’ political support of and financial investment in the opposition political parties and civic movements, trying to prove that the events occurred in several post-Soviet countries were caused by an attempt to further restrict Russia’s influence through creation of a “sanitary cordon” around it. The truth is, however, not that simple and unequivocal. One should not deny that a number of American NGOs and U.S.-financed local civil society organizations have really developed projects and other activities in order to strengthen the liberal democratic values in the CIS. Beyond any doubt, this was meant to enhance the opposition movements, parties and civil society as those projects’ natural counterparts. These activities could be interpreted either as a sincere aspiration to assist the newly independent states in their drive for democracy or as an attempt to impose alien values through interference in the internal affairs of the states in question. More than that, one could also argue that the U.S. and the West, in general, had their own geo-political agenda, which in light of the above-mentioned trends of deepening dividing lines were really meant to broaden their sphere of influence under the guise of progress and democracy.

Notwithstanding all these arguments, as true as they might seem, one cannot refrain from making a rather paradoxical conclusion. The paradox is that although the target of the harsh critics of the “orange revolutions” is “foreigners” and their “agents of influence”, in reality, they aim at the peoples of those countries. Indeed, such analytical exercises suppose that the role of peoples, their right to make a meaningful choice and express their will through democratic electoral procedure is nothing more than pure formality. The electorate, thus, is reduced to be a mere instrument for regime change, which can easily be manipulated under the influence of foreign ideas and money. Is not this a highly cynical and disdainful approach toward the people, whose interests the contributors of the above-mentioned book pretend to defend with all their analytical wisdom and energy.

Apart from this somewhat emotional argument, one should provide with the main objection to the “conspiracy theory” in post Soviet countries. As a matter of fact, this “theory” totally ignores the primary importance of the internal prerequisites and factors, which are a condition sine qua non, when it comes to regime change. In other worlds, you can spend billions of dollars, you can train armies of NGOs, you can guide the opposition political parties’ activities, and all the same, you will be doomed to a failure, if the opposition does not have any more or less significant popular support. Otherwise, how could be explained the fact that regardless of rather substantive and consistent political and material support to opposition political parties, individuals and civil society representatives in Belarus, the regime change there could not take place in the past and to all evidence would not occur in the foreseeable future either.

The Belarusian context has already been discussed in this article. It remains to reiterate that Lukashenko’s rule will come to an end only by virtue of internal factors. Belarus, like any other country, has been developing, and this development will bring about either an open, democratic society or unification with Russia. It is impossible to say with certainty, when this time will come. But it is possible to say with certainty that in both cases Lukashenko will leave the political scene. He is fit to rule the country as an authoritarian leader, but not as a democrat or a vassal.

Armenia can serve as another eloquent example against the “orange revolution” theory. Here too the opposition could not topple Kocharian’s and his follower Sargsian’s regime for the same reason of lack of internal prerequisites and conditions. Nonetheless, if in Belarus the opposition’s failure was due to the obvious lack of support by the bulk of population, in Armenia the reason can be explained by another phenomenon.

Armenia, perhaps, is the most kakistocratic country in the post-Soviet area. This does not require any lengthy explanations. Suffice to mention two black dates in the country’s recent history: 27 October 1999, when the President of Parliament and the Prime Minister along with six MPs where massacred by an armed gang at a parliamentary session, and 1-2 March 2008, when 9 demonstrators and a policeman were killed in the aftermath of peaceful protest rallies, organized by the leader of the opposition, first President of Armenia Levon Ter-Petrossian, and triggered by the rigged presidential election of 19 February 2008. The gravity of situation in today’s Armenia stems not only from the tragic nature of these events but also, and even more, because the perpetrators have not been discovered up until now and no one believes they would be discovered under the current regime.

Nevertheless, the situation in 2008 in Yerevan was very similar to that in Tbilisi in 2003 and in Kiev in 2004. Why then the massive popular protests in Yerevan were unable to annul the falsified election results with a predictable outcome of Ter-Petrossian’s return to the presidential office. This can be explained by two major reasons. First, the kakistocratic leaders of Georgia and Ukraine did not go as far as to crash the popular protests by heavily armed groups, including snipers, as it was the case in Yerevan. Second, Ter-Petrossian himself was the founding father of kakistocracy in Armenia. In early 1990s he and his cronies from the Armenian National Movement started the country’s systematic plunder. Electoral fraud, merger of state structures with the oligarchic ones, impoverishment of the bulk of population against the background of enrichment of a handful of kakistocrats – all this was initiated by Ter-Petrossian. By virtue of this fact alone, he could not win the battle. He was doomed to failure by definition. Hence, there is little wonder that in the most critical situations during February-March 2008 he was unable to demonstrate courage and determination to guide the people’s will and resolve the crisis in favour of justice and democracy. Thus, Ter-Petrossian’s inability to lead, as well as the absence of any other opposition leader, who might live up to the expectations of the people at the most critical historic moment, became a major reason for the “apricot” revolution’s fiasco.

In cases of both Belarus and Armenia the reasons for failure to achieve regime change goes to the internal factors. True, one should not underestimate the role of external support, but this role is always a secondary and subordinate one.

The theory of “orange revolutions” is false. In the final analysis, it serves to justify the post-Soviet kakistocratic regimes’ unwillingness to give up the Cold War mentality and the confrontational way of striving for their domestic and foreign political interests. First of all, this concerns Russia, which in pursuit of its overall goal of restoring the lost influence has opted for straightforward pragmatism so alien to its national spirit. But a broadminded national leader would, perhaps, find an alternative and much more attractive ways of enhancing and promoting Russia’s strategic agenda both internally and externally.

Conclusion

In 1918, a year after the collapse of the monarchy in Russia the great Russian thinker Nikolai Berdiayev wrote:,There is no longer great Russia and there are no longer universal tasks in front of it…” Surprisingly precise and perspicacious words. Russia’s greatness and incentive for achieving and preserving its influence can be based only on spiritual values. This has been many times proven by history itself. Russia can lead and achieve tremendous results provided it has an idea, an ideology, a universal- and historic-scale mission to accomplish. The Russian Empire has expanded and achieved a great deal of economic prosperity and political influence not that much due to its military power as thanks to its central idea of “orthodoxy, monarchy and nationhood”. The practical undertakings of the Russian Empire stemmed from this triad and created a prerequisite for its attractiveness. Paradoxically enough, even the Soviet Union preserved a great deal of attractiveness for many peoples of the third world who linked their hopes for overthrowing the colonialist regimes having recourse to the Marxist-Leninist ideas. Although these ideas proved to be false and unrealistic, the important here is that even communist Moscow could be and was for a certain period of time a centre of attractiveness. Thus, the Soviet expansion was due not only to the military force, but to the country’s ideological doctrine whatever false and even disastrous it might be. The conclusion is obvious: Russia can restore its influence not through military power and natural resources but through restoring its attractiveness and by means of engaging itself in the fulfillment of great tasks vis-à-vis the historic challenges that humanity faces at this stage of development. But for that, Russia needs a great leader who could live up to the magnitude of the challenges. This in turn will not be possible unless the country has not gotten rid of kakistocracy.

This article has quoted Dr. Narochnitskaya’s comparison of “orange revolutions” to an unconstitutional attempt to topple the existing rulers. The post-Soviet countries’ experience has clearly demonstrated that she is, and this is yet another paradox, absolutely right. The kakistocratic regimes are able to take any measures all without distinction to keep their power at any rate, because power is the source of their richness and self-esteem, it is their raison d’être, and there is little wonder that they will never give it up voluntarily. Either they will do that under the huge pressure of insurgent people or they will permanently and consistently falsify the elections, stifle individual rights and freedoms, introduce an atmosphere of fear for the others and lawless permissiveness for themselves.

Here we come to another conclusion: there are only minimal, if at all, chances to get rid of kakistiocratic regimes within the constitutional framework. The kakistocrats’ lawlessness and lack of legitimacy must be tackled by adequate means. It is impossible to topple illegal power by legal means or, the other way round, any means to topple the kakistocrats’ illegal rule is legal. In some countries this scenario has worked without bloodshed, like in Czechoslovakia, in some other countries, unfortunately, it was not possible to avoid violence, like in Romania. But the logic of historic events was the same.

The kakistocratic regimes inevitably lead to deterioration of the political and socio-economic situation, as well as to degradation in terms of basic values and elementary human behaviour not only internally. They create permanent tensions also externally, representing, in the final analysis, a serious threat to international peace and security. After all, one cannot artificially divide the nature of internal and external policy of a given state. Both are conducted by a single leadership and both stem from the same principles be they constructive or destructive. The question is: what will be the answer of the international community, first of all, the EU and the U.S. vis-à-vis such a situation?

While this topic requires an in-depth analysis, here it should be briefly underlined that the West has only two options: 1) either to work toward the kakistocratic regimes’ isolation in the hope that this will accelerate the regime change from inside and, at the same time, will neutralize to the extent possible the threats stemming from those regimes; or 2) to cooperate with the kakistocratic regimes in the hope that common objectives can be found and common goals, such as combating terrorism and international organized crime or achievement of Millennium Development Goals can be pursued jointly, thus creating a window of opportunity for those regimes’ gradual mitigation and promoting external prerequisites for internal changes.

Whereas the effectiveness and efficiency of either option to destroy kakistocracy are far from being obvious, the preference most probably should be given to the second one. It is only through cooperation, through elaboration and implementation of a joint platform to achieve common goals would it be possible to overcome the overall crisis of identity and establish a balance between selfish state interests and the common objective of preserving and promoting universal values.

Originally published by the Journal of Eurasian Studies 1:2 (July 2010, 153-163) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.