The school segregation issue was ripe for being brought to the first tier of social concerns.

By Dr. Jean Van Delinder

Professor of Sociology

Associate Dean of the Graduate College

Oklahoma State University

Introduction

“Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments.”

Chief Justice Earl Warren, Opinion on Segregated Laws Delivered May 1954

When the United States Supreme Court handed down its unanimous decision in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case fifty years ago this spring, it thrust the issue of school desegregation into the national spotlight.

The ruling that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” brought racial issues into the forefront of the national consciousness as never before and forced all Americans to confront a racially divided society and undemocratic social practices. At the same time, the decision opened the floodgates of decades of school desegregation suits in both the North and the South.

But the ruling did much more than that. It gave impetus to a young civil rights movement that would write much of American history during the next few decades.

The school segregation issue was ripe for being brought to the first tier of social concerns. Elsewhere in American society, segregation was breaking down.

Important steps were taken in 1941, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, forbidding racial discrimination by any defense contractor and establishing a Fair Employment Practices Committee as a regulatory agency to investigate charges of racial discrimination.

In 1947, Major League Baseball saw its first black player in Jackie Robinson. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman ordered the desegregation of the armed forces, which had already seen black and white Americans fighting side by side in World War II. That same year, under the guise of states’ rights, racial issues split the Democratic Party.

School segregation came at a high cost even outside of the human costs. For example, school districts had to maintain two school systems within one geographical area. Prior to 1954, Topeka, Kansas, maintained half-empty classrooms in segregated schools in order to keep the races separate. After Brown, this pattern continued with racism disguised as “freedom of choice”—justifying building new schools in outlying areas as merely a response to the population shift to new subdivisions rapidly being built in the western areas of the city (which turned out to be predominantly white and upper class). Left behind were the less affluent, primarily black, residents who had little choice but to send their children to outdated and increasingly inferior schools.

Brown also caused Americans to revisit the role of the national government in regulating local issues. Century-old arguments, reminiscent of the debates over slavery, were revived to defend the primacy of states’ rights over federal jurisdiction. The same language used to defend slavery was now being used to defend segregation. Words like “interposition” and “nullification”—which hadn’t been heard for more than a century—were used to defend school segregation.1

Just as the Civil War caused Americans to confront the ugly reality of slavery, so too did Brown inspire Americans to confront its undemocratic system of education.

In recognizing the importance of education as the foundation of a democratic society, the Brown decision expressed the sentiments of Thomas Jefferson that publicly funded education was to be the primary mechanism to develop a natural elite and to ensure that the new republic had a literate citizenry regardless of social class. Jefferson’s beliefs were reflected in the words of Chief Justice Earl Warren, who justified the significance of education in the Brown decision as being “the very foundation of good citizenship.”2

The Topeka Brown case is important because it helped convince the Court that even when physical facilities and other “tangible” factors were equal, segregation still deprived minority children of equal educational opportunities.

Over the years, numerous scholars have traced the history of the Brown case and analyzed its impact as federal legislation. Yet most of these studies have been written from a national perspective, distant from the day-to-day life of the local people most affected by school desegregation.

The Topeka Brown records provide a glimpse of what people were doing in their local communities, where the struggle for racial justice was a continuing reality, year in and year out. The records help us to understand the reality of school segregation in places like Topeka, where it was only legal in the elementary schools. What was the effect of “separate-but-equal”?

Overview of the National Case before the Supreme Court

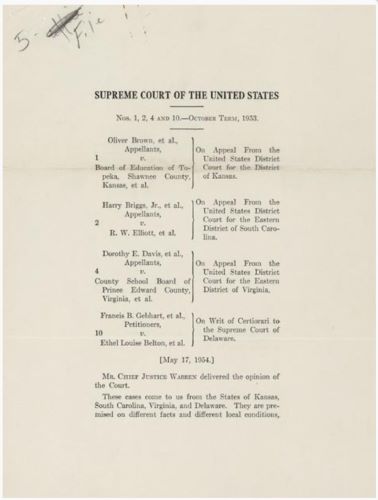

In October 1952, the Supreme Court announced it would hear five pending school desegregation cases collectively. In chronological order, the five consolidated cases were 1949: Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al. (South Carolina); 1950: Bolling v. Sharpe (District of Columbia);3 May 1951: Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al. (Virginia); June 1951: Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (Kansas); October 1951: Gebhart et al. v. Belton et al. (Delaware).

These cases all document inadequate funding for segregated schools—meaning that many black children lacked playgrounds, ball fields, cafeterias, libraries, auditoriums, and other amenities provided for white children in newer schools. In Summerton, South Carolina, and Hockessin, Delaware, school buses were only provided for whites, while black children had to walk. In Claymont, Delaware, and Farmville, Virginia, there was no senior high school for black pupils.

The Brown case of Topeka, Kansas, itself included twelve other plaintiffs besides Oliver Brown, whose daughter Linda was being bused twenty-one blocks from her home to a segregated school. The nearest school in her neighborhood was only a few blocks away, but it was for whites only.

All of these cases were appealed to the Supreme Court, and the first round of arguments were held December 9–11, 1952. The following June, the Supreme Court ordered that a second round of arguments be heard in October 1953. When Chief Justice Fred Vinson, Jr., died unexpectedly of a heart attack in September, President Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated California Governor Earl Warren to replace Vinson. The Court rescheduled Brown v. Board arguments for December. On May 17, 1954, the Court declared that racial segregation in public schools violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, effectively overturning the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision mandating “separate but equal.”

The Brown ruling directly affected legally segregated schools in twenty-one states. In 1954, seventeen states had laws requiring segregated schools (Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware), and four other states had laws permitting rather than requiring segregated schools (Kansas, Arizona, New Mexico, and Wyoming). Kansas’s state statutes restricted segregated elementary schools only to cities, such as Topeka, that had populations of more than fifteen thousand.

Though the 1954 ruling declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, it did not specify how this was to be remedied. Originally the Court scheduled arguments on this subject for later in the year, but it did not hear what would become the third round of arguments in Brown until April 1955.4 On the last day of its term, the Supreme Court ordered desegregation to begin with “all deliberate speed.”

In the intervening year, the District of Columbia and some school districts in other states had voluntarily begun to desegregate their schools. However, state-sanctioned opposition to desegregation was already well under way in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia, where the Court’s decision had been declared “null, void, and no effect.” Across the South, schools were closed and public education was suspended. Public funds were disbursed to parents to subsidize the education of their children in private schools. Some states even went so far as to impose sanctions on anyone who implemented desegregation.

Effects of the Supreme Court Decision in Kansas

In Topeka, resistance to desegregation was more indirect, subtle, and covert. Historically, the color line in Kansas was more permeable than it was South Carolina or Virginia. Its “border state” ideology was directed more toward racial collegiality and inclusion than animosity and exclusion. Kansas had relatively permissive segregation statutes (compared to some southern states).

For example, segregation was permitted in elementary schools where the population exceeded fifteen thousand (cities of the first class). The one segregated high school—Sumner High School in Kansas City, Kansas—had been established in 1905 after a special act of the legislature allowed segregation of a secondary school in this one instance. However, Kansas’s permissive racial statutes served to disguise the underlying reality of an unwritten code of racial separation that rivaled locales where total de jure public segregation was practiced. Topeka’s continued segregation of its public school system after Brown illustrates how the dismantling of a de jure system of segregation does not necessarily include the end of racist social practices.

Over the several decades following Brown, covert opposition to desegregation was carried out under cover of school redistricting and convoluted attendance boundaries. It was also aided by real estate developers riding the postwar housing boom, who urged white Topekans to buy new houses and move to the newer—and racially homogenous—western suburbs. The City of Topeka obliged this migration by annexing western territory several times between 1950 and 1979. There was a corresponding rise in demand for more schools from the Topeka Board of Education and its successor, Unified School District #501. Between 1957 and 1966, Topeka witnessed the creation of an “alternative predominantly white, school sub-system generally around the peripheral boundary but specifically concentrated in the southern and western portions of the Topeka school system.” New schools built after 1959 would have pupil racial ratios that would be all or disproportionately white. Additionally, classroom additions and portable classrooms would be primarily placed at disproportionately white schools.

Though the official end of segregation in 1954 met with far less hostility in Kansas than in Mississippi or South Carolina, African Americans still encountered obstacles. News correspondent Carl T. Rowan had found Topeka to be a “pretty segregated city” when he lived there as a navy trainee during World War II. Returning to Kansas in 1953, he described his earlier experiences by observing, “Topeka was a paradox. There was no Jim Crow in some areas where you had expected it; segregation had deep roots where it was not expected.”

The state’s permissive segregation laws meant that overt segregation was strictly limited, while covert segregationist practices arose unrestrained. “There was no segregation on city buses, or in any public transportation,” Rowan recalled. “But I was unable to go to a movie or into a restaurant with white navy buddies. Hotels, bowling alleys and other public recreation facilities were closed to Negroes.”

A decade later and just a few months before the first Brown decision, Rowan still found it difficult to find a restaurant willing to serve him and his companion, attorney Charles Scott, the original lawyer involved in the Brown case. Despite the legal demise of segregation, informal segregation was still intact. Rowan and Scott were asked by one restaurant owner to eat in the kitchen not because of any law requiring racial separation, but simply because it was his “policy.” As an attorney, Scott understood that it was much easier to remove segregation laws than to confront and change the informal racial practices that permeated the embarrassing day-to-day reality of racial segregation. “And it stems from Jim Crow schools,” Scott declared to Rowan as they left one restaurant without being served, “because when segregation is part of the pattern of learning it permeates every area of life.”

Early Challenges to School Segregation in Topeka: 1900–1950

In Kansas, the antecedents of the Brown case can be traced back through eleven previous lawsuits challenging segregation. Beginning in 1880, these suits all challenged the legality of school segregation as it was practiced in Kansas.5 Of the three cases that involved Topeka’s schools, two are especially relevant to the Brown case. The earliest case, dating from 1901, involved the introduction of segregation in recently annexed areas (the Reynolds case), and the other case (the Graham case in 1940) involved the decision of whether or not junior high schools fell under the state’s segregation statutes.

Similar patterns of racial upheaval and containment, begun with the annexation issues related to the Reynolds case and the limitation of segregation to elementary schools as illustrated by the Graham case, continued throughout the Brown litigation.

The issues involved in both of these cases were the effect of segregation itself on public education, the system of social practices that had arisen around it, and whether segregation as it existed was a violation of the due process clause in the Fourteenth Amendment, the same issues involved in the Brown decision.

“In approaching this problem,” Chief Justice Warren wrote in 1954, “we cannot turn the clock back to 1868 when the [Fourteenth] Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.”

In Kansas, both the Reynolds and Graham cases illustrate the development of the issues that came to fruition nationally in the Brown case.

The Reynolds Case

On February 1, 1901, William Reynolds tried to enroll his eight-year-old son Raul in the new school that was reserved for whites. When he was refused, Reynolds filed suit on behalf of his son. In the complaint, the court record stated that

Because of race and color, and for no other reason whatever, his child has been and is excluded from attending school in said new building by the express order and direction of said board . . . thus putting publicly upon the plaintiff and his child the badge of a servile race, and holds them up to public gaze as unfit to associate, even in a public institution of the state, with other races and nationalities, in violation of the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments to the constitution of the United States, and, in violation of said fourteenth amendment, denies to the plaintiff and his child the equal protection of the laws.

The context behind the Reynolds suit was related to the geographical circumstances of Topeka. The westward growth of Topeka was caused in part by its being geographically constrained by the Kansas River to its north and southeast. Due to the contours of its flood plain, the least desirable land was north and east of the city, an area that came to be predominately African American. The more desirable land—which rarely flooded—was toward the west and south, and was predominately white. This pattern of settlement would continue throughout the twentieth century.

In the 1890s, the city of Topeka annexed part of a rural district, No. 91, south and west of the town’s center, locally known as the “Lowman Hill District.” Being a rural district, No. 91 did not have segregated schools. After annexation it continued to be integrated because “it did not become convenient or expedient to make provision for separate schools . . . until the said school building was destroyed by fire.” After a fire occurred on July 20, 1900, the district implemented segregation by ordering that the fifty African American children living in the area be forced to attend classes in an old building that had been moved to the original site of the burnt-out school and outfitted with second-hand furniture. The district then built a new school for the 130 white children living in the area, which brought about the Reynolds suit.

Reynolds ultimately lost his case, and his son had to attend a segregated school. The school board argued that the new school building was larger and more centrally located in order to accommodate the white children, who outnumbered the African American children living in the area.

We see that as early as 1901, the parents of white children were able to enjoy the benefits of sending their children to newer, neighborhood schools while the parents of African American children had to send their children to segregated schools, many of which were not located close to where they lived.

The Graham Case

Just as land annexation resulted in a challenge to segregation, so too did the shift toward junior high curriculum bring another challenge to Topeka’s segregated schools with the Graham case. When the segregation statutes were first written in 1861 and later modified in 1879, junior high schools did not exist, and very few people of any race went on to high school. The subsequent redefinition of state segregation statutes after 1940 was in response to an innovation in the institutional structure of public education accompanied by rapidly increasing enrollments in secondary and post-secondary institutions.

When Topeka adopted the junior high system, it implemented a different educational curriculum for seventh and eighth grade students based on race. White students were provided with a 6-3-3 system, consisting of six years of elementary or grade school, three years of junior high school, and three years of senior high school. Black children were under an 8-1-3 plan.

The 8-1-3 plan meant that African American children in Topeka remained in segregated schools through the eighth grade, choosing either to enter an integrated ninth grade at Boswell Junior High or remain in a segregated class by electing to attend Roosevelt Junior High. White children who left elementary school after sixth grade and attended junior high school were consequently introduced to a much more specialized curriculum.

The court transcript of the Graham case illustrates the differences between the segregated elementary schools and the junior high schools. When the plaintiff, who had just finished sixth grade, tried to enroll in Boswell Junior High School, he was refused admittance on the basis of his race. He filed suit, claiming the course of instruction offered at Buchanan Elementary was not equal to that available at Boswell Junior High.Boswell was a new facility and built for the express purpose of being a junior high. It contained many more classrooms than the elementary schools, allowing for students to change classes for specialized teaching. In the segregated schools, one instructor taught most of the subjects.

At segregated Buchanan School, one teacher taught most of the math and English courses, while at Boswell Junior High School different instructors taught all these subjects. In the testimony provided by witnesses in the Graham case, the home economics teacher at Buchanan, Miss Ruth Ridley, reported that though her students were well prepared when they graduated from the eighth grade, they did not have facilities comparable to the better equipped and more up-to-date sewing and cooking rooms at Boswell.

Graham won his case: The junior highs in Topeka were legally desegregated. However, the effect was uncertain—desegregation did not include the teaching and administrative staff. For example, after the Graham case, eight African American teachers lost their jobs due to the integration of the junior highs. The assumption that the curriculum was not equal to the white schools reflected poorly on the high dedication and exemplary training of the black teachers, which many of them rightly resented. At two of the four segregated schools in Topeka, more of the teachers held master’s degrees than at any of the white grade schools.

Though no formal policy existed to not hire black teachers, it soon became obvious in Topeka that the number of African American teachers slowly dwindled after April 1953. Before the Brown decision, Topeka had 27 African American teachers who taught 779 students. By 1956, the number of African American pupils had increased to 898, but the number of full-time teachers had declined to 21. After the desegregation of the elementary schools in 1954, for most black teachers in Topeka and elsewhere, Brown did not result in integration; it still meant segregation or even worse, unemployment. This decline in employment of black teachers after integration is a largely unacknowledged fact of desegregation.

Contemporary Challenges to School Segregation in Topeka: 1950–1985

By 1950, the Topeka school system had twenty-two elementary schools (9.6 percent black), six junior high schools (9.9 percent black), and one senior high school (7.6 percent black). As permitted by state law, racial segregation of students at the elementary level was strictly adhered to. The four schools that were maintained for black students were Buchanan, McKinley, Monroe, and Washington. Each of these four schools was geographically located in predominately black areas, although students were brought in from throughout the system. Five of the eighteen white elementary schools were located in predominately white areas, while the remaining thirteen schools, though reserved exclusively for whites, were located in racially mixed neighborhoods.

Segregation was maintained at a considerable cost as the four segregated elementary schools had much smaller student enrollments than their white counterparts. In 1950, all four of the segregated schools had an average of 143 pupil spaces underutilized, while the all-white schools were much more crowded, averaging only 28 spaces underutilized. The average black school had an enrollment of 165 students, while the white schools had an average enrollment of 342. Topeka did not use the available classroom space in the black schools to relieve overcrowding in the white schools. Given that thirteen of the eighteen schools reserved for whites were in racially mixed neighborhoods, it would have been relatively simple to reassign pupils without the additional expense of providing transportation.

Racial segregation was sustained over the next thirty years as the Topeka School Board constantly changed boundary lines ensuring that some its elementary schools remained segregated, and its high schools became more segregated than they were before 1954. In 1955, three former all-black elementary schools were still 100 percent black with only 1 percent of its black children attending elementary schools that were formerly for whites.

From 1931 to 1958, Topeka had one, integrated, senior high school: Topeka Senior High School. Five years after the original Brown decision, when faced with the opportunity to continue the racial parity at the senior high school level that had already existed for more tan twenty years, the Topeka Board of Education made a series of decisions that ensured that racial segregation would be compounded by class. As city boundaries expanded to the south and west, two more high schools were added: Highland Park Senior High School, acquired through annexation in 1959, and Topeka West Senior High School, opened in 1961. The aging Topeka Senior High now had 83.2 percent of the black students in the Topeka school system assigned to it while was approximately 11 percent black, and Highland Park was 5.1 percent black. One year later, were now being Topeka High, while Highland Park had 6.5 percent and Topeka West had 0.3 percent.

The 1960 U.S. Census data indicates that the largest concentration of Topeka’s black population with school-age children resided midway between Topeka High and Highland Park. A simple change in the attendance boundary when Highland Park was annexed would have brought its minority enrollment to 50 percent. It would have also alleviated overcrowding at Topeka High, since Highland Park had 497 empty seats. Instead, the Topeka School Board elected to build a third high school (Topeka West) at the western fringe of the growing city, assigning to it 2 black children and 702 white children.

Twenty years after Brown, in 1974, the Topeka school system (U.S.D #501) still underutilized predominately black schools while white schools remained overcrowded. For example, there was a 15.1 percent black enrollment at the elementary level, but more than half of them (56.7 percent) were assigned to seven schools, while the nine of the remaining eleven had an average of 4.5 black children assigned to each of them.

Two of those schools, McClure and Potwin, were all-white in 1974. On September 10, 1973, Johnson v. Whittier was filed as a class action brought on behalf of “all Black children who were then or had during the past ten years been students of elementary and junior high schools in East Topeka and North Topeka.” The complaint concentrated more on “equality of facilities than distribution of students, alleging that the children in West Topeka and South Topeka received vastly superior educational facilities and opportunities, including buildings, equipment, libraries and faculties, than could be obtained by students in the areas of East Topeka and North Topeka, which contained higher percentages of minority students.”

Though Johnson failed to qualify as a class action suit, it did set off an investigation by the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) into “the practices of the Topeka public schools regarding race discrimination.” This investigation led HEW to prepare to cut off federal aid to Topeka schools for desegregation noncompliance and to schedule an administrative hearing. This action also resulted in the filing of U.S.D. #501 v. Weinberger, No. 74-160-C5. Though on August 27, 1974, Johnson moved to consolidate with Weinberger, this motion was never decided. The Weinberger case was later dismissed after the Topeka school district’s motion for a preliminary injunction was granted by a U.S. district court judge, who found that the district court, and not HEW, had jurisdiction over Topeka’s school desegregation.

The school board argued that it was in compliance with the original desegregation plan that was approved by the district court on October 28, 1955, and fully implemented by September 1, 1961. Since the junior high schools were desegregated before Brown in the early 1940s, and the high school was never segregated, they were not considered to be part of the original court order. Additionally, the school board argued that the district court has “exclusive jurisdiction to determine whether or not the Topeka school system is in violation of the Final Order of Judgment and the Court approved plan for desegregation.” The HEW attorney disagreed, stressing, “that while the original plaintiffs in our case were attacking segregation at only the elementary school level, HEW was charged with investigating discrimination in all its aspects at all levels of the public school system.” Meanwhile, two other class action suits related to illegal segregation were filed on August 8, 1979 (Miller v. Board of Education), and September 7, 1979 (Chapman v. Board of Education).

The original Brown case had targeted legal, or de jure, segregation. But it could not address de facto segregation, or the type of segregation that was the “natural” outgrowth of an individual’s choice and their financial resources allowing them to live in any given neighborhood. In 1979 the Brown case was reactivated.

The original lead plaintiff, Linda Brown, now an adult, and other African American parents and their children argued that the Topeka School Board and its successor, U.S.D. #501, had failed to desegregate within the mandates of Brown and Brown II, in which the court in May 1955 ordered that desegregation proceed with “all deliberate speed.” Between September 10, 1973, and September 7, 1979, four separate cases were filed in the federal district court of Kansas raising questions as to whether the Topeka Board of Education and its successor had complied with the mandates of the high court. Though these cases resulted in minor judgments, they did prompt an investigation by the Office of Civil Rights of the federal Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). HEW found that Topeka was not in compliance and brought further attention to the ways in which the Topeka Board of Education sought to circumvent desegregation.

The reopening of Brown in 1979 tried to prove that the resegregation of Topeka’s schools was not the “natural” consequence of individual choice, but rather the result of the deliberate actions of U.S.D. #501 to segregate its more affluent citizens (primarily white), who had fled to its western suburbs, from the less affluent (primarily black), concentrated in East Topeka. Because the school board had designed and built schools with the effect of limiting access to its newer facilities to only those residing in Topeka’s western suburbs, most African Americans in Topeka were relegated to East Topeka’s rapidly aging and increasingly inferior schools.

Not only were African Americans geographically bound to attend inferior schools, they were also now economically limited by not having the financial resources to purchase homes that automatically provided them access to newer and better schools. By the 1970s, Topeka was more spatially and economically segregated than it had been before Brown.

There was one important difference: segregation was no longer based on race so much as it was on class, even though being “black” and being “poor” were fast becoming synonymous, not only in Topeka, but in many other American cities as well. The 1970 census showed that in Topeka, Kansas, the mean family income in the wealthy, predominately white West Hills area was triple that of the predominately black southeast area: $19,909 to $6,886. This statistic is also reflected in the 1970 median value of housing, $28,800 in West Hills to $9,550 in East Topeka.

In October 1986 the reactivated Brown was tried in the District Court of the District of Kansas. Six months later the plaintiffs appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit when the district court decided that there was not enough evidence of purposeful discrimination.

On December 11, 1989, the court of appeals voted to reverse the findings of the lower court. The school district appealed to the Supreme Court, but on April 20, 1992, the Supreme Court sent the case back to the court of appeals for further consideration. The appellate court reaffirmed its earlier decision and denied rehearing on January 28, 1993.

A few months later on June 21, 1994, the Supreme Court declined to consider the matter further. Finally, on July 25, 1994, the district court approved the school district’s third desegregation proposal, but the school district continued to be subject to the court’s jurisdiction.

Conclusion

As the Brown case files demonstrate, by choosing not to distribute the responsibility of desegregation over the entire school system, the Topeka Board of Education, and its successor U.S.D. #501, used its administrative tools in an ongoing manner to actively separate black from white.

What is even more disturbing is that after 1954, not only was there continued segregation at the elementary level, but it had also crept into the middle, junior, and senior high grades as well. Segregation after 1954 was perpetuated not on racial lines but class lines. That class incorporated the race most affected by segregation made it even more pernicious than before Brown.

The issues involved in this case are far from resolved. Unlike segregation laws, the social practices that arose to circumvent Brown fifty years ago are much more difficult to overcome.

Endnotes

- “Interposition” was a doctrine declared unconstitutional before the Civil War, supposedly allowing states to “interpose” their own authority in order “to protect their citizens from unjust actions of the federal government.” It was resurrected to justify continuing school segregation as early as November 1955 in an editorial by James Kilpatrick that appeared in the Richmond News Leader. W. D. Workman, Jr., “The Deep South,” in Don Shoemaker, ed., “With All Deliberate Speed” (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1957), p. 97.

- Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al. 347 U.S. 483 (691).

- The U.S. Supreme Court filed a separate opinion on Bolling because the Fourteenth Amendment was not applicable in Washington, D.C. In this case, the Court held that racial segregation in the District of Columbia public schools violated the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.

- This delay was related to the sudden death of Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson. To fill the vacancy, President Eisenhower nominated John Marshall Harlan in October 1954. Ironically, Harlan was the grandson of Justice John Marshall Harlan, the lone dissenter in Plessy. In 1896, Harlan wrote the prophetic words in his dissent that “separate but equal” would forever stamp blacks with a badge of inferiority. This same type of argument would prove a decisive factor fifty years later in Brown.

- The following eleven cases reached the Kansas Supreme Court:

Board of the City of Ottawa et al. v. Leslie Tinnon (1881);

Knox v. Board of Education, Independence (1893);

Reynolds v. Board of Education, Topeka (1903);

Cartwright v. Board of Education, Coffeyville (1906);

Rowles v. Board of Education, Wichita (1907);

Williams v. Parsons (1908);

Woolridge v. Board of Education of Galena (1916);

Thurman-Watts v. Board of Education of Coffeyville (1924);

Wright v. Board of Education, Topeka (1929);

Graham v. Board of Education, Topeka (1941);

Webb v. School District No. 90, South Park Johnson County, Kansas (1949).

Originally published by Prologue 36:1 (Spring 2004), the United States National Archives and Records Administration, to the public domain.