Rivers did not stay put. Coastlines receded. Earthquakes reshaped terrain. These disruptions did more than challenge surveying crews or legal offices.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Fragile Lines in the Landscape

The nineteenth century is often remembered for its aggressive cartography. Lines were drawn across deserts, jungles, and rivers, frequently with more ambition than understanding. Empires, both European and emergent, projected themselves across continents by way of treaties, maps, and military encampments. Yet behind this facade of control lay a simple but often ignored truth: the Earth did not always cooperate.

Here I consider the geographic instability that challenged imperial and national boundaries in the nineteenth century. Far from being fixed, many borders proved vulnerable to erosion, earthquakes, floods, and other natural forces that reshaped the physical landscape. In a period dominated by ideologies of permanence and possession, nature often defied the paper-thin authority of colonial and national claims. The fault lines beneath empires, both literal and metaphorical, were active. This is a history not of diplomacy or ideology, but of the stubborn materiality of land and water.

Shifting Rivers and the Problem of Fluid Frontiers

Perhaps no natural force was more persistently disruptive to border-making than the river. Throughout the nineteenth century, empires and nations attempted to use rivers as clear and convenient boundaries. The logic seemed sound. Rivers could be mapped, watched, and defended. They flowed through remote terrain where other markers might fail.

Yet rivers move.

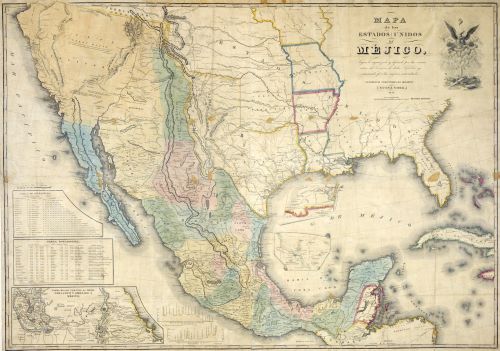

The Rio Grande, serving as a contentious boundary between the United States and Mexico after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, shifted its course repeatedly in the decades that followed. In cases such as the 1895 Chamizal dispute, entire parcels of land changed sides as the river meandered or flooded its banks.1 These changes sparked legal and diplomatic confusion, with landowners caught between shifting sovereignties.

European colonies in Africa faced similar challenges. In the Congo basin, seasonal flooding and river migration made it nearly impossible to enforce or even identify colonial borders on the ground.2 The assumption that rivers were stable, linear dividers proved untenable. Hydrology revealed the weakness of inked maps when confronted with the natural movements of sediment and water.

Erosion, Coastlines, and the Vanishing Edge

While rivers played havoc with inland frontiers, coastal erosion undermined the very outlines of maritime power. In the Netherlands, long known for its delicate balance between sea and land, the Wadden Sea region lost sections of territory as storm surges ate away at dikes and islands.3 In the United Kingdom, the east coast experienced accelerated erosion in places like Holderness, where villages that had existed for centuries were swallowed by the sea within decades.

Colonial holdings were not immune. The French presence in Senegal was challenged by shifting coastal dynamics near Saint-Louis, where barrier islands and tidal forces threatened the infrastructure that undergirded colonial administration.4 In these cases, nature not only eroded beaches and roads but blurred the imagined permanence of the colonial presence. When the very land beneath one’s feet disappears, sovereignty becomes abstract.

Earthquakes and the Illusion of Fixed Territory

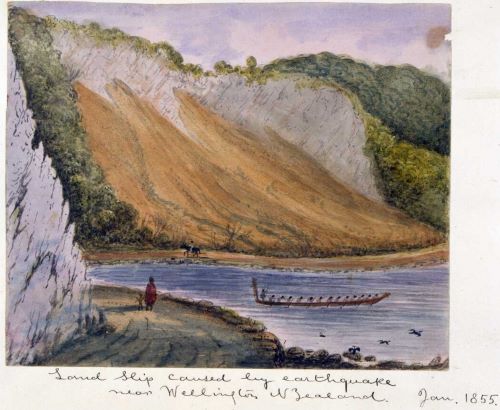

Tectonic activity introduced even more dramatic revisions. In 1855, New Zealand’s Wairarapa earthquake lifted portions of the North Island by more than six feet in a matter of seconds.5 This sudden geological transformation created new coastal lines, reshaped river paths, and disrupted Maori land claims, which were based not only on occupancy but on precise knowledge of natural markers. British colonial authorities, already struggling to impose a coherent land tenure system, found themselves negotiating a landscape that no longer matched their surveys.

In South America, the 1868 Arica earthquake and tsunami devastated parts of coastal Peru and Chile. Not only did these events cause massive destruction, they redrew shorelines, destroyed ports, and disrupted border logistics in regions where territorial disputes already simmered.6 The material rupture of the land became entangled with political contestation, a literal upheaval of statecraft.

Floods, Ice, and the Fragile Northern Frontiers

In the northern latitudes, the Canadian and Russian empires encountered different but equally destabilizing forces. Seasonal ice flows along the Mackenzie and Lena rivers tore away at posts, settlements, and trading routes. Floods, especially in spring, altered drainage basins and changed the utility of waterways that had once defined fur trade corridors or supply lines.7

These disruptions mattered not only for logistics but for legal geography. If a boundary treaty identified a specific river or natural feature, and that feature ceased to exist in its original form, could the treaty still stand? The imperial response was often to ignore or overwrite these discrepancies, but local populations were not so easily convinced. Indigenous groups, in particular, found colonial boundaries increasingly unmoored from lived geography. The land remembered differently than the maps.

Conclusion: The Earth Writes Back

The nineteenth century was an era obsessed with claiming land, delineating it, and naming it. The empires of the time operated under the illusion that territory could be rationalized into measurable, knowable units. Yet the Earth itself refused to behave.

Natural forces repeatedly exposed the fragility of imperial boundaries. Rivers did not stay put. Coastlines receded. Earthquakes reshaped terrain. These disruptions did more than challenge surveying crews or legal offices. They revealed the hubris at the core of colonial and national expansion: the belief that the material world could be subordinated to human abstraction.

Today, as rising sea levels redraw shorelines and meltwater shifts the shape of continents, the history of unsteady borders in the nineteenth century resonates with renewed urgency. The lesson is not merely that nature resists control. It is that sovereignty itself remains a negotiation with the ground beneath us.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Paul Ganster and Kim Collins, Borders and Border Politics in a Globalizing World (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 66–69.

- Richard Reid, A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present (Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 113.

- P. D. Jones and T. M. L. Wigley, “Global Warming Trends over the Past Century,” Nature 332, no. 6159 (1988): 790.

- David Anderson, Histories of the Hanged: Britain’s Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 31.

- G. A. Eiby, “The 1855 Wairarapa Earthquake,” New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 4, no. 2 (1961): 101–118.

- Charles F. Walker, Shaky Colonialism: The 1746 Earthquake-Tsunami in Lima, Peru, and Its Long Aftermath (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 12–14.

- Liza Piper, The Industrial Transformation of Subarctic Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009), 77–82.

Bibliography

- Anderson, David. Histories of the Hanged: Britain’s Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

- Eiby, G. A. “The 1855 Wairarapa Earthquake.” New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 4, no. 2 (1961): 101–118.

- Ganster, Paul, and Kim Collins. Borders and Border Politics in a Globalizing World. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

- Jones, P. D., and T. M. L. Wigley. “Global Warming Trends over the Past Century.” Nature 332, no. 6159 (1988): 790–791.

- Piper, Liza. The Industrial Transformation of Subarctic Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009.

- Reid, Richard. A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Walker, Charles F. Shaky Colonialism: The 1746 Earthquake-Tsunami in Lima, Peru, and Its Long Aftermath. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.14.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.