The story of Rome’s relationship with its river ultimately underscores the eternal co-evolution of society and environment.

By Dr. Andrea L. Brock

Lecturer in Classics and Archaeology

University of St. Andrews

Abstract

This case study considers the trajectory of Ancient Rome’s urban development in its riverine environment. Recent geoarchaeological investigations in Rome’s river valley have shed light on the pre-urban setting and landscape changes that occurred alongside urbanization. With these new discoveries and a rich corpus of archaeological and historical evidence, Rome offers one of the longest records available for exploring how rivers impact cities and cities impact rivers.

In order to build in their flood-prone lowlands in the mid-1st millennium BCE, the inhabitants of Rome engaged in large-scale landscape modification projects and flood mitigation measures. Urbanization at Rome, however, triggered fresh ecological challenges, including rapid sedimentation and escalating floods. The inhabitants of Rome responded to their volatile river with a range of adaptive strategies. Over the centuries, they continued to mitigate the effects of overbank flooding through the use of strategic urban planning, land reclamation, flood-resistant architecture, and bureaucratic oversight of the riverine landscape. It is noteworthy that, despite having the capabilities, the ancient Romans chose not to enact large-scale engineering projects to prevent floods altogether. The so-called Eternal City, therefore, should be seen as a resilient city—one that persevered in the face of dynamic ecological conditions and recurrent inundations.

This article emphasizes the value of historical applications for modern sustainability studies: the past offers both empirical evidence and a vibrant perspective for conceptualizing the complexities of human-environment interactions over many centuries. The story of Rome’s relationship with its river ultimately underscores the eternal co-evolution of society and the environment.

Introduction to Case Study

According to a United Nations report, more than half of the world’s population currently live in cities—with urban habitation projected to grow exponentially in coming decades. The spread and increasing density of urban space has wide-ranging implications for local and regional ecosystems; cities, therefore, represent a significant component of present and future sustainability challenges. This case study employs a focused historical survey of the so-called Eternal City, in order to sketch the complexities of city-river interactions from Rome’s origins though to the early 20th century. As one of the largest cities of the pre-modern world, Rome offers unique perspectives on the challenges and consequences of urbanism as they play out over the long-term.

Rome sits in one of the most dynamic types of landscape on our planet: a river valley. Many cities around the world, ancient and modern, arose near rivers, in large part because of the wealth of agricultural and commercial opportunities. The process of urbanizing a river valley, however, creates particular ecological challenges. Rivers are shaped by and actively shaping their surrounding landscape over short and long timescales. These high-energy waterways are extremely susceptible to changes within their environment: human activity, in particular, can substantially impact fluvial systems. As evident at Rome, powerful natural and human forces operating simultaneously can lead to significant transformations that have reverberating consequences within the ecosystem. By drawing on historical data—including some recent discoveries from geoarchaeological investigations in Rome’s river valley—we can elucidate both the ways in which urban growth affects riverine landscapes and the means of inhabitants’ resiliency.

This case study has been employed in the Ancient History classroom, where it offers new insights on prehistoric Rome and one of the most salient qualities of later Roman culture: a strong willingness and capability to adapt to challenging environments. Long before the creation of their empire, the earliest inhabitants of Rome learned to alter their landscape and respond to changing ecological pressures as they built their city in the first millennium BCE. For students of Ancient History, environmental archaeology supplements conventional accounts of Rome’s origins—which have long relied on a problematic literary record and potentially tenuous comparisons with other communities in central Italy—by providing new empirical evidence on Rome’s urbanization process.

Even more important than creating new conceptions of this one ancient society, environmental history provides an invaluable laboratory for studying the co-evolution of societies and environments over time.1 In order to envision and create a sustainable world in the future, we must appreciate that our modern predicament is ultimately the result of historical processes. Understanding how we got here and how societies proved resilient in the past will help prepare us to respond effectively to our present challenges.

This case study specifically explores the ecological challenges to city building in a flood-prone region, environmental change as a riverine system goes from unmanaged to highly managed, and a range of urban flood mitigation measures. With sea levels rising due to global warming, rivers and coasts around the globe will become increasingly susceptible to sedimentation and flooding; communities positioned on these waterways are expected to be threatened by more frequent floods of greater magnitude. When preparing for urban growth and more severe flooding in the future, policy makers can look to the historical impacts of urbanization on comparable ecosystems and begin to assess the efficacy of various adaptive strategies. Additionally, historical cases can inform and underpin efforts to predict the repercussions of future climate change. As an example, the long history of flooding at Rome starkly corroborates a recent attempt to model flood exposure in modern cities:2 flood mitigation efforts can prove to be wholly inadequate in a relatively short period of time, as areas once thought safe from inundation become increasingly vulnerable to changing conditions. Such analogous stories of past human experience can helpfully illustrate ecological processes to a popular and non-specialized audience, which may not engage with scientific models.

In order to address effectively the myriad of ecological challenges before us, history offers rich sources of data from infinitely complex systems. A growing army of historians, archaeologists, and paleoecologists are striving to employ lessons from the past to help us prepare for the uncertainties of our future.3

Case Study

Benvenuti a Roma

Modern Rome is a sprawl of buildings and roads, bustling with mopeds weaving though throngs of tour groups. The infamous seven hills are today somewhat lost in the homogenized landscape, and the Tiber River—a powerful protagonist in the city’s early history—is now isolated by towering embankment walls (Fig. 1). Indeed, the average tourist could wander the streets for days without ever setting eyes on the river that flows through the heart of the city. But if we imagine peeling back this dense urban accumulation, layer by layer, traveling back in time, we would eventually expose a much different scene. Although it is difficult to envision a landscape that existed more than two and a half millennia ago, it is this extinct setting that contains clues to Rome’s origins and its historical trajectory.

The origins of Rome have long remained an elusive subject. The literary and documentary record from Rome post-dates the beginnings of the city by several centuries. Much of the “history” of early Rome, such as the story of the twin founders, Romulus and Remus, is really mythical, first recorded when Rome was already the head of a growing empire.4 Most of the archaeological traces from this early period, moreover, are either lost or buried beneath two and a half millennia of subsequent urban growth. These barriers long made research into the birth of the Eternal City frustratingly limited.

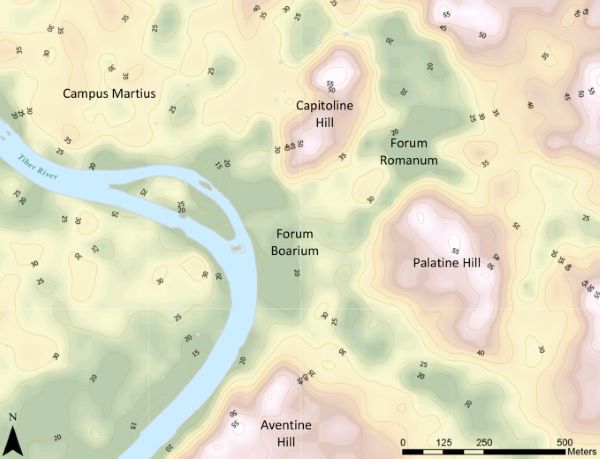

Fortunately, though, a series of deep excavations in recent decades and the growing application of environmental methodologies are beginning to revolutionize our conception of Rome’s urbanization process, creating a picture of an incipient city dramatically altering the landscape and inhabitants who were compelled to adapt to dynamic conditions. Working with an international team of archaeologists and earth scientists since 2013, I have directed an extensive geoarchaeological investigation of Rome’s central river valley, the Forum Boarium (Fig. 2). River valleys serve as uniquely rich repositories for examining human-environment interactions over a long time span, because they contain deep sedimentary records that are formed by the river’s depositional behavior and shaped by activity on the surrounding landscape. The Forum Boarium Project has used deep coring survey to expose archaeological and geological stratigraphy deposited in the Tiber River valley more than 2000 years ago and buried more than 15 m below the modern street level.5 This novel method has proven effective for accessing the earliest levels of human activity in Rome, thereby allowing us to reconstruct more clearly the pre-urban landscape and document transformations that occurred alongside the growth of the city.

The Advantages and Challenges of Rome’s Riverine Landscape

Rome’s natural landscape was the product of a dynamic, high-energy environment, forged since the Pleistocene by volcanic and fluvial forces. Between 600,000 and 300,000 years ago, a series of volcanic eruptions produced huge pyroclastic deposits that left a high plateau in the area of Rome. This soft volcanic stone, called tuff, was subsequently eroded and deeply incised by the Tiber River and its tributaries. These geological processes left the topography that would characterize the later city: a collection of steep-walled hills separated by low-lying valleys in one of the most flood-prone sections of the Tiber River.6 This setting offered both opportunities for and challenges to urban growth at the site of Rome. In addition to the accessibility of fresh water and arable land as well as trade and communication networks, Rome’s particular position along the Tiber River afforded important ecological advantages that made the site especially appealing for human habitation:

- High hills provided a defensive position.

- Valuable natural resources, including salt and high-quality clay deposits. Salt, an important dietary supplement and means to preserve meat, was a vital commodity in the pre-modern world, and clay sources were exploited for ceramic pottery and roof tile production.7

- At a point of confluence with two tributary streams, the valley widened and the river slowed, offering a natural harbor and ford. People traveling north–south along the western coast of Italy could cross the river at this point. Additionally, sailors on the Mediterranean Sea, which would find no convenient harbor along the Latial Tyrrhenian coast, could row or be towed about 15 miles upriver, where they could beach their ships at a low-lying section of riverbank in the Forum Boarium.8

Later Romans, reflecting on the achievements of their earliest ancestors, seem to have recognized the many advantages provided by their landscape. Writing in the 1st century BCE, Roman statesman Cicero effuses about Rome’s mythical founder:

“The placement of a city is something which must be done with the most diligent foresight by one who attempts to beget a long-lasting state, and Romulus chose a site with incredible opportunity… the city was able receive from the sea what it needed and export what it had in excess; the city could import goods greatly needed for a cultured life not only from the sea, but also receive goods carried over land.” (De Re Publica 2.5–10)

It is important to remember that Cicero’s musings about Rome’s origins at the hands of a venerable founder is purely speculative, influenced by mythical tales that perpetuated over the centuries. Although the city of his day was drastically different than the settlement he imagined existing some 700 years earlier, nevertheless, Cicero rightly concluded that Rome’s position in the Tiber River valley and in the Mediterranean more broadly provided major economic opportunities for its inhabitants.

The proximity to the river, while advantageous, also meant that location was prone to flooding. When the Tiber overflowed its banks, which presumably occurred perennially during the rainy winter season, Rome’s valleys would have been inundated. In the earliest centuries of settlement at the site of Rome, this seasonal flooding likely did not cause major problems. Archaeologists have identified traces of human settlement at Rome dating to the Late Bronze Age (late 2nd millennium BCE); the available evidence indicates that this habitation was on a relatively small-scale and limited to clusters of huts on the hills.9 Although the valleys undoubtedly hosted a variety of activities in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages—for example, agricultural and pastoral pursuits, as well as harbor activity adjacent to the riverbank—there is no evidence of contemporary built infrastructure in the lowlands. Considering that the primary building material of the era was mud-based wattle and daub, structures built in the floodplain would have been seriously undermined on an annual basis. We can assume, therefore, that either lowland activities did not require physical structures or inhabitants accepted periodic destruction and were prepared to rebuild with inexpensive and readily available materials. Moreover, when Rome was inundated, inhabitants could temporarily disband their valley activities and quickly move to the safety of the hills. Later Romans, themselves familiar with the issue of flooding, envisioned their early ancestors coping thusly: “When the river overflowed, as it often did, they used to cross it at about this point in ferry-boats” (Plutarch, Life of Romulus 5.5). Although undoubtedly an inconvenience, floods in this early period probably caused minimal death and destruction.

This ecological situation, while tenable in a pre-urban context, would become more problematic as the settlement grew and began to use the lowland spaces in more substantial ways. Boating between the hills was impractical, and it is possible that the valleys would have remained inhospitable even after floodwaters receded. Pools of stagnant water left by retreating floodwaters would breed mosquitoes, which had the potential for carrying malaria.10 In order to build the city of Rome, therefore, inhabitants were compelled to modify their riverine landscape and make early urban investments seemingly aimed at mitigating the impacts of flooding.

Early Flood Mitigation Efforts at Rome

The archaeological record demonstrates that the 6th century BCE was a transformational period: Rome evolved from disjointed hut settlements into a cohesive urban center. It is noteworthy that, as one of the earliest undertakings in the construction of their city, early inhabitants chose not to restrict themselves to the relative safety of the hilltops but to build in the river valley. Indeed, the first temple built in Rome (known archaeologically) was positioned directly on the bank of the Tiber in the vicinity of the river harbor. Excavations have revealed the temple’s stone podium and associated altar, dating to the early 6th century BCE.11 Atop the stone podium would have stood a temple building of wattle and daub walls and capped with a ceramic tile roof and lavish architectural decorations, including statues to Hercules and Minerva (now on display in the Musei Capitolini). The temple is generally associated with the cult of Fortuna, given the deity’s association with the later sanctuary in the same location. The goddess of fortune was certainly an apt figure for a harbor setting, as sea travel and cross-cultural interaction in the ancient Mediterranean were often perilous and unpredictable.

Although the riverbank in the Forum Boarium was of vital importance for the movement of people and goods through the harbor, this district would have flooded first and most often, making it particularly vulnerable position for such architectural investments. Recent geoarchaeological investigations, however, have revealed that the temple was strategically placed on a part of the landscape that was notably higher than the rest of the river valley: a raised section of riverbank that extended out from the base of the Capitoline Hill.12 Apparently shielded from the erosive forces that kept the surface in other parts of the valley much lower, this section of riverbank stood more than 5 m higher than the floodplain immediately south, where boats arriving at Rome in the prehistoric era could have been pulled ashore. The 6th century harbor temple, atop a nearly 2 m tall podium on the high riverbank, was therefore situated in a prominent position and at an elevation that would have offered it protection from the threat of floodwaters.

Not far from the riverbank, a large-scale land reclamation project was undertaken in the valley between the two major hills of Rome: the Capitoline and Palatine. In order to support a growing population and permanent structures, this flood-prone lowland needed to be addressed. Archaeological explorations in the valley indicate that up to 20,000 m3 of sediment were dumped into the low lying basin, raising the ground level by nearly 2 m in the initial instance.13 This monumental enterprise would have required the cooperation and labor of many individuals and seems to have been specifically designed to lift the ground level away from the threat of floodwaters, so that even when the Tiber River spilled over its banks, there would have existed a land bridge between the Capitoline and Palatine Hills. This investment in land reclamation provided valuable new space for the growth of public institutions, including some of Rome’s earliest political and religious spaces. Eventually this district would become known as the Forum Romanum, the civic heart of the city.

In conjunction with this reclamation project, the Romans began building an extensive drainage system. The first phase of this infrastructure, known as the Cloaca Maxima or Greatest Sewer, drained water from the newly reclaimed Forum Romanum to the Tiber River, helping to speed the drying process after an inundation. Although it originated as an open-air channel for a tributary stream of the Tiber, eventually the Cloaca was enclosed and buried beneath further landfills.14 An advanced piece of infrastructure even in its original form, this underground system was rebuilt, expanded upon, and maintained throughout the ancient period, so that it served to move both water and waste into the river. Even today, the mouth of the ancient Cloaca Maxima remains visible as it terminates at the eastern bank of the Tiber River (just south of the Ponte Palatino).

When the first permanent structures were erected in Rome’s lowland, inhabitants employed a multi-faceted strategy arguably designed to accommodate the Tiber’s flooding regime and prevent at least some destructive consequences. A variety of measures were utilized early in the city’s history—exploiting high points of the landscape; using stone podia to elevate structures; land reclamation and raising the ground level; drainage systems and canalization of tributary streams—and would continue to be used for centuries thereafter. As they urbanized, however, their landscape transformed, exacerbating the very problem they were seeking to address. As the city grew, the river changed, and as the river changed, inhabitants were compelled to adapt further.

River Dynamism

Coring in Rome’s river valley has revealed that the landscape was radically altered alongside this early phase of major urban growth. After many centuries of relative stability and slow sedimentation, in the 6th century the Tiber River shifted its course westward and silts deposited by overbank flooding began to rapidly accumulate at the margins of the river in the area of the Forum Boarium. The geoarchaeological evidence indicates that a staggering 5.8 m of sediment accumulated over the course of the 6th century BCE alone.15 Fluvial sediments neared the elevation of the Temple of Fortuna, so that in just a few generations, a position that was once largely protected from the threat of floods became extremely vulnerable. Changes to the river’s hydrological regime also reshaped the valley’s topography: as the once low-lying shore of the river harbor silted up, and a wide, high section of riverbank emerged in its place. The sedimentation in the area of the Forum Boarium continued at least into the 3rd century BCE, raising the ground level in parts of the river valley by as much as 10 m.

With the currently available evidence, it is difficult to identify with certainty the causes of this change to the Tiber’s position and depositional behavior. Rivers are highly dynamic and sometimes volatile. They can shift their bed, erode large swaths of land, and create new floodplains. They are susceptible to climate change, precipitation fluctuations, and even small-scale modifications of sediment or hydrological inputs and outputs. In addition to these natural forces, however, it must be noted that anthropic activity can create considerable instability in riverine landscapes.

Based on the archaeological record, Rome’s urbanization in the 6th century appears to have been both rapid and large-scale. In just a few generations, the Romans reclaimed a sizable portion of its lowland and invested in more than a dozen monumental structures.16 In order to support the documented construction activity and presumably growing urban population, timber would have been exploited as a building material and their primary fuel source. Although much of the area around modern Rome is currently devoid of dense forests, paleobotanical evidence indicates that central Italy was once heavily forested before the spread of human settlement. In addition to impacts on the land, deforestation has significant repercussions for a riverine system. As trees are cut down, sediment becomes readily eroded from slopes and washed down into the river valley. Unfortunately, the ancient pollen data is currently limited, so it is difficult to track the chronology of local deforestation. Later anecdotes, however, suggest that by the early first century CE, forests as far as Pisa (roughly 200 miles away) were being exploited in order to meet the demand for timber in Rome,17 presumably because resources closer to Rome had already been exhausted.18 Although the evidence is not definitive, it is nonetheless highly suggestive of a connection between urban growth, deforestation, and changes to the Tiber River.

This period of major fluvial dynamism not only triggered sedimentation capable of complicating operations around the river harbor, but also appears to have contributed to an increase in flood magnitude. As the city grew and the ground level in the valleys rose (both as a result of sedimentation and land reclamation projects), there was reduced space to accommodate floodwaters. The available evidence suggests that flood waters reached greater heights over time. Coring survey in the river valley has exposed alluvial sediments characteristic of flood deposits dating to the 6th century BCE at an elevation of 6 m above sea level (masl); these reach up to 9 masl by the 3rd century BCE. By the 1st century BCE, the historical record of flooding in Rome indicates that buildings at substantially higher elevations—as high as 20 masl—were threatened by floodwaters.19 With the spread of paved surfaces and the encroachment of buildings, flood waters endangered new areas at a higher elevations and greater distance from the river. The Roman historian, Tacitus, evocatively portrays the result in his account of a flood that struct Rome in 69 CE:

But a particular terror not only of present but also future destruction came with a sudden inundation of the Tiber, which in a huge surge destroyed the Sublicius bridge and was stopped only by a huge heap of rubble. It flooded not only the low-lying and level areas, but also those usually safe from this sort of catastrophe [emphasis added]. Many were swept away from the public squares and many more were cut off in their shops or beds. There was famine among the masses due to lack of employment or provision. The foundations of apartment buildings were degraded by the stagnant waters only to collapse when the river receded. (Histories, 1.86)

Rome’s challenges with floods persisted as the city grew and initial mitigation efforts were quickly rendered inadequate in the face of changing conditions.

Adapting to a Changing Landscape and Escalating Floods

Lacking a modern awareness of geological processes, the early inhabitants of Rome were unable to predict how their investments in urban infrastructure and deforestation could cause reverberating environmental consequences. Nor could they foresee how the patterns of Tiber floods would change over time, so that the adaptive efforts of one generation proved to be insufficient sometimes even in a matter of a few decades. While the Romans responded in a variety of ways over the centuries, their actions focused on accepting the inevitability of flooding and mitigating the effects of floodwaters, rather than attempting to prevent floods altogether.

The archaeological record shows that the Romans began to adjust their urban investments in the valleys by the late 6th century and would continue to do so over time. Although we lack a textual record until the 3rd century BCE to hear from the Romans themselves about the challenges they faced, the archaeological evidence speaks volumes: the early 6th century Temple of Fortuna, which had stood on the raised section of riverbank for only two or three generations, was abandoned, and in its place the Romans constructed a 6 m tall platform against the lower flank of the Capitoline Hill.20 This drastic response suggests that the Romans were adapting to novel flood threats. The renovation of the harbor sanctuary in the early 5th century—which required both the forfeiture of a divine structure and a sizeable investment of resources and manpower—established a new, artificial terrace that stood once again several meters above the river. On top of this large platform, the Romans once again aggrandized their riverbank with two new temple buildings (the ruins of which are still visible today at the archaeological zone around the Church of Sant’Omobono). This enormous effort to lift structures away from floodwaters can be seen elsewhere, particularly the Forum Romanum, where a series of landfills progressively raised the ground level, presumably in response to floods of ever-increasing magnitude.

With the notable exception of this sanctuary complex atop its artificial platform on the riverbank and the reclaimed land in the Forum Romanum, huge swaths of Rome’s lowlands were not urbanized for several centuries. The process of building in a floodplain changes the ecology that leaves a discernible mark in the geoarchaeological record: once an area is paved, it is logical to expect that sediment deposited by floodwaters would be cleaned up, rather than left to accumulate over time. In the region of the Forum Boarium, coring survey shows that sediment continued to accumulate at least until the 3rd century BCE. We can infer, therefore, that even as the city of Rome grew significantly into the mid-Republican period—and even as Rome became the dominate force in Italy—the Romans continued to operate without significant physical investments in much of their river valley. Another lowland area, the Campus Martius (the plain to the north of the Capitoline Hill which would also have been susceptible to flooding) was similarly used for seasonal activity that required minimal urban infrastructure. Whereas the Forum Boarium hosted commercial pursuits, the Campus Martius was originally exploited for military and athletic exercises. Only sporadic architectural features existed in the Campus Martius until Augustus made significant investments in the region in the early 1st century CE. By limiting the scale of urban development in lowland areas, therefore, the Romans could minimize the destructive consequences of flood events.

Eventually, however, the urban sprawl of Rome did stretch into the valleys in substantial ways and thus created new vulnerabilities. There is evidence that Romans began investing in embankment walls along the river as early as the 3rd century BCE, if not earlier. These structures, however, do not appear to have been aimed at preventing incursions from the Tiber. The available evidence of embankment walls at Rome throughout the ancient period suggest that they were low in certain areas and not the kind of cohesive line of high walls, which would be necessary to contain floodwaters.21 Instead, these walls served other important purposes: reinforcing the riverbank and shielding it from erosion, as well as providing mooring structures to secure boats. Atop these embankments, new architectural investments would define Rome’s riverscape: most notably, temple buildings resting on high podia, which would help them withstand floods. Even once the river valley was urbanized, the area would require regular maintenance. Among other activities, repeated dredging was necessary to clear the Tiber channel of debris and sediment, facilitating boat boating activity and creating accommodation space for flood waters.22 Flood events would have required clean up efforts to remove deposited silts as well as the periodic reconstruction of destroyed structures. By the Late Republic, there came a formalized governmental response: bureaucratic offices, curatores alvei et riparum Tiberis or overseers of Tiber’s bed and banks, were created presumably in order to help manage the demands of riverbank maintenance and flood response.23

With the advent of the historical record, we gain some deeper insight on the Romans’ discussions around the floods that beset their city. Even beyond efforts to manage and mitigate, it is worth noting that they also considered more radical efforts to control their volatile river. For example, in the 1st century BCE, Julius Caesar made a proposal to modify the course of the Tiber by constructing an artificial canal that would divert the Tiber’s flow away from the city entirely.24 Following a devastating flood in 15 CE, the emperor Tiberius appointed a special commission to address the issue.25 The Roman Senate debated various strategies, including engineering that would redirect or dam sections of the Tiber and its tributaries and control the amount of water outflow in the fluvial system. These aggressive measures, however, were ultimately not enacted.

It must be emphasized that by the late 1st millennium BCE the ancient Romans had the engineering capabilities to protect their city from floods, whether through the use of dams, artificial levees, canals, or other measures.26 Indeed, they pursued many large-scale landscape modification and hydrological control projects throughout their empire.27 The fact that they did not prevent floods in their capital was, therefore, at least partially a choice, not entirely an inevitability. There are numerous potential explanations for this seemingly irrational judgement, but three reasons should be highlighted. First, the Romans had an appreciation for the fact that rivers are complex systems: by obstructing or redirecting waters, risks would have been shifted to other communities in the region.28 Damming projects were ultimately discarded, in part because of the objections of other communities, which feared an increase in flooding or the loss of agricultural land.29 Second, technological innovations, particularly the invention of hydraulic concrete (which can set underwater and remain resilient in wet environments) in the late 2nd century BCE, significantly improved their ability to construct urban infrastructure in areas near the river.30 Indeed, the Romans eventually made major investments in port infrastructure along both banks of the Tiber, which ensured the importation of food stuffs and other goods necessary to support the city at its estimated peak of more than one million inhabitants.31 Finally, the Romans had religious reverence for the natural world.32 Many features of the landscape, including rivers, were seen to have divine essence. Rivers like the Tiber were often personified as gods (Fig. 3), and natural disasters like floods were interpreted as omens from the gods. Overt efforts to alter the environment or control the river would therefore have religious connotations.33 The ancients’ veneration of the gods should be understood as another adaptive response that offered some sense of control over their situation: by appeasing the gods, they may look favorably on the city and withhold natural disasters.

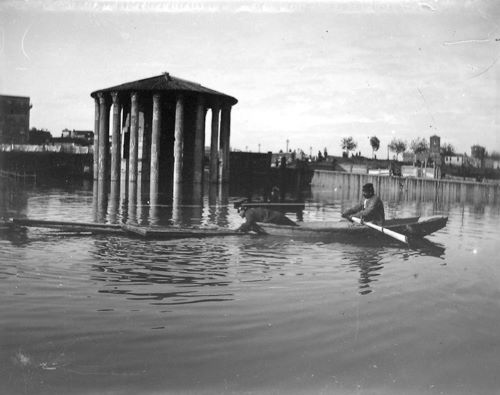

Continually susceptible to the Tiber’s fluctuations, Rome was affected by inundations and the devastating secondary effects of malaria well into the modern period.34 In the generation after Rome was made the capital of the newly unified nation of Italy in 1870, a series of significant floods submerged huge swaths of the city for several days. Photography at the turn of the century captured the adaptive capabilities of modern Romans, who boated around their city just as their prehistoric ancestors supposedly had (Fig. 4). Faced with this recurring threat to his new capital, the Italian King, Vittorio Emanuele II, strove to modernize Rome and organized a commission to develop a plan to prevent such disasters.

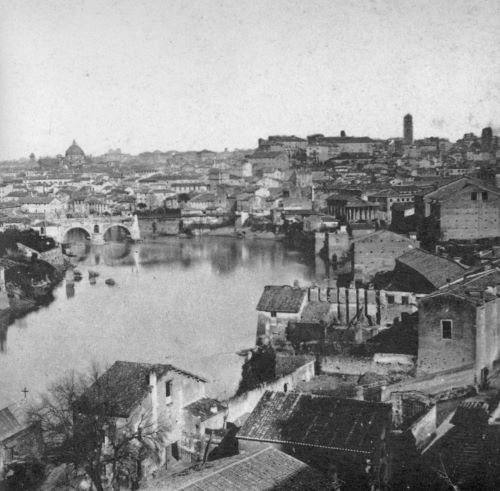

Officials explored a variety of strategies, including renewed discussion about rerouting the Tiber away from the city entirely. Ultimately, the decision was made to conduct a massive overhaul of the area along the Tiber River, which had been heavily encroached upon over the centuries (Fig. 5). Buildings that lined the riverbank were demolished, and by the completion of the project in 1910, the entire length of the river as it travelled through the city was encased in 40-foot high concrete walls (see Fig. 1). After the city had been afflicted by inundations for more than two millennia, this enormous urban renovation and investment in flood walls finally ensured that the lowlands of Rome would be protected from overbank flooding. Now, when the city experiences issues with flooding, which is not entirely uncommon, this is often the unpleasant result of heavy rainfall and blockages in the city’s sewer system.

Lessons from the Eternal City and Its Relationship with the Tiber River

Rome was heavily shaped by its proximity to and its early reliance upon the Tiber River. In order to build their city, the ancient Romans had to negotiate a complex relationship with their environment and accept considerable risk. A wealth of archaeological and historical evidence from Rome highlights the degree to which riverine systems can be transformed by urban development. Additionally, this case study demonstrates how flood risks can intensify over a period of many centuries, so that flood mitigation strategies of one generation can prove to be wholly inadequate in the next. The complexity of this city-river interaction demands a multifaceted approach that draws on communal cooperation and government leadership, which can effectively engage with a variety of challenging questions:

- How does the city use or rely upon the river?

- Can and should the river be controlled?

- What does a sustainable city-river relationship look like?

- How will continued urban growth exacerbate the effects of floods in a decade? In a century?

- Which urban spaces are most vulnerable to flooding today, and how might currently safe areas be jeopardized in the future?

- In what ways can building in floodplains be limited or managed?

- Which flood mitigation measures have proven to be effective or ineffective over the long term, and why?

- In what ways will flood control measures shift the risk to another part of the fluvial system?

- How does access to wealth and resources (or lack thereof) affect a community’s ability to cope with recurrent urban floods?

Although answers to these questions will undoubtedly vary from community to community, a global history of resilient riverine cities can offer invaluable perspective to help decision-makers and communities anticipate changing conditions, explore adaptive strategies, manage risks, and envision sustainable growth. Looking to the past can help us understand our place in the present world and prepare for the future.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by World Development Perspectives 26:100426 (June 2022) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license.