By Dr. Thora Hands

Professor of the History of Alcohol and Drug Use

City of Glasgow College

Introduction

This provides three case studies of Victorian alcohol producers and retailers: Bass & Co, a major brewer based in Burton-upon-Trent; whisky producers James Buchanan and John Walker whose companies expanded the market for Scotch whisky in England and W & A Gilbey, one of the leading wine and spirit merchants in the late nineteenth century. Each of these companies operated in an increasingly competitive market for alcoholic drinks. It was therefore necessary to adapt business models and commercial practices to secure profits from the sale of wines, beers and spirits.

Although each case study tells a different story, they share some commonalities. Each company realised that selling alcohol in late Victorian Britain required a degree of cunning, ingenuity and a leap of imagination in order to circumvent temperance ideology and reach an expanding consumer market. People did not need to be given reasons to drink—despite decades of the Temperance Movement, many continued to do so. However there was profit to be made in marketing alcohol as a socially acceptable (and sometimes desirable) drink that not only had health-giving properties but also embodied British cultural ideals.

Selling ‘the Drink of the Empire’: Bass & Co. Ltd

This part considers the tactics of the brewing industry by focusing on one of the largest and most successful brewers in Britain, Bass & Co. Ltd. In order to compete in a growing domestic and foreign market for beer, Bass began to use advertising as a means of reaching larger groups of consumers. By appealing to notions of Britishness and Empire, Bass secured a market for their products and established a strong brand image. The company also used ideas about the supposed health giving properties of beer in order to boost dwindling sales towards the end of the century.

It is easy to see why pale, bitter ale made great headway in the 1840-1900 period, the golden age of British beer drinking. It was novel, bright, fresh and pale; it looked good in the new glassware; it was the high fashion of beer of the railway age. Perfected in Burton, it was, by the 1870s, produced everywhere.1

Tastes in beer changed during the nineteenth century and this was driven in part by the expansion of the brewing industry and also by changing social attitudes and leisure pursuits.2 Although regional breweries continued to produce a variety of beers that catered to local markets, one of the key national changes was a general shift in tastes from strong dark beers and porter to light sparkling beers and ales. This is largely attributed to the expansion of the brewing industry in Burton upon Trent in the 1840s which was driven by the development of India Pale Ale (IPA).3 Burton brewers, Allsopp and Bass began developing a heavily hopped, pale bitter beer for the Indian export market in the 1820s. IPA was developed to survive long sea voyages and hot climates and was therefore a successful export commodity to India and the colonies. Foster attributes the commercial success of IPA not only to its robust qualities, which made it a safe and pleasant alternative to local drinking water but also because for colonists, it evoked ideas about Britishness.4

The development of IPA and can be traced to the October ales which were produced in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Beer production was closely aligned with the agricultural seasons and the beers brewed at the beginning of the season used the freshest hops and malt right after the autumn harvest. The practice of using exclusively pale malt was expensive and was therefore usually found among country estate brewers who catered to the wealthiest country gentry.5 By the mid-eighteenth century, commercial brewers in London were also producing pale beers alongside darker beers and porter. However, pale beer was more expensive and was therefore viewed as a status drink which was popular among the upper classes, many of who became colonists in India. The market for pale ales was closely linked to the expansion of the British Empire and also to the spread of imperial ideology. This was one of the key reasons for the commercial success of Bass & Co. which produced and exported the largest volume of IPA in the late nineteenth century.

Following the railway expansion in the 1840s, the Burton brewers began to develop variants of IPA for the domestic market. Up until that point IPA had not been sold in Britain and although it is likely that the Burton brewers seized upon a commercial opportunity to cultivate domestic tastes for pale ale, a more exciting story circulating at the time claimed that a ship carrying a cargo of IPA destined for India was shipwrecked in the Irish Sea and the cargo was salvaged and sold off in Liverpool where local drinkers sampled it and liked the taste.6 As Jonathan Reinarz notes, ‘shipwreck theory’ provides an attractive explanation for the commercial success of IPA because it supports the prevalent historical view that nineteenth-century brewers spent very little time or resources on marketing and advertising.7 The Bass records support the idea that there was more to the commercial success of pale ale than simply ‘success by chance.’ In fact, the larger Burton brewers such as Bass & Co., spent considerable amounts of money on advertising pale ale and expanding the domestic market for its products.

Bass brewery was a family business established in Burton upon Trent in the 1770s. The company initially supplied local pubs and inns in the surrounding areas. Then in the late eighteenth century, it merged with another local brewer, Samuel Ratcliff and together they built a strong export trade to the Baltic region. When the Baltic trade began to fail after 1800, the company again merged with another local brewer John Gretton and trading as ‘Bass, Ratcliff and Gretton’ turned its attention to cultivating trade links to India and the colonies by developing and exporting IPA.8 The company also extended its reach into the domestic market. Between 1850 and 1880 25% of beer and ale sales went to the London market; 18% were exported; 22% were distributed locally and 35% were sold by other agencies.9 By the 1880s, Bass was producing approximately 850,000 barrels per year with the production of pale ale accounting for 56% of total output.10 The company also secured its share of the domestic market through the tied house system and by buying licensed premises in Burton and surrounding areas and in London.11

When Alfred Barnard visited Bass & Co. in 1889, he described the brewery as a major part of Burton’s ‘beer metropolis.’12 Barnard was a journalist with a particular interest in the drink trade. He published detailed accounts of his tours around various breweries in Britain and Ireland and seemed to be particularly impressed with the production site at Bass & Co. where he found that ‘a steady and undeviating perseverance of uniformity, order and regularity, is discernible in all the buildings and breweries connected with Bass & Co.’s establishment.’13 The detail in Barnard’s account conveys the sheer enormity of the Bass production site which included 12 miles of railway track connecting all the buildings in the company grounds. Barnard was clearly impressed with the production process which used modern brewing equipment and employed analytical chemists to test and enhance the quality of products. This was brewing on a truly modern and industrial scale. However, the volume of output was not enough to maintain and promote the company’s share of the market. It was, therefore, important to create a distinct brand identity that would be associated with all Bass products. During his tour, Barnard visited the bottle-labelling department, which he described as

… a large and important one in this establishment. [It] is conducted by a Superintendent and several clerks. The well-known red triangle or pyramid, in the centre of the oval label, used for Bass & Co.’s bottled pale ale is one of their numerous trademarks and has been in use by them for upwards of fifty years.14

The red triangle or ‘pyramid’ and the red diamond were in fact the first British company trademarks to be registered under the Trade Marks Registration Act in 1842. Bass was aware of the need to protect the brand identity and the company kept a label book which contained various Bass labels and those used by rival companies. This book contained labels from c. 1870 to 1924 which appear to have been used as a means of keeping a record of the development of new product labelling and also of any attempts by rival companies to copy Bass product branding. Bass also kept an Infringement Book which contained evidence of any fraudulent attempts to copy or use Bass product branding. One undated entry in the book titled ‘Bass & Co.’s advertisements—case to advise’ stated

Bass, Ratcliff and Gretton Ltd are the owners of a trademark in the form of a triangle which is coloured red. Certain public houses where their beer is to be obtained have painted on the window adjoining the public house the triangle and in some cases there is the addition of ‘Bass & Co.’s Ales’ too … Strangers seeing the mark on the windows are drawn into the house under the impression that they can obtain Bass & Co. ale. We have no evidence as to whether they ask for Bass & Co. ale and are supplied in draught or in bottle with ale either by no remark being made as to whether it is Bass & Co. or not, but there is no doubt that keeping up the mark attracts customers.15

The company invested considerable time and resources in order to protect the brand from fraudulent use. An online search of the British Newspaper Archive for ‘Bass Pale Ale labels’ (1850–1900) generated numerous reports of prosecutions for false labelling of products. For example, in 1859 The Belfast Morning News reported the case of a local wine and spirit merchant charged with purchasing quantities of pale ale and falsely labelling the bottles with an imitation Bass logo.16 Another similar case reported in The Manchester Courier in 1886 was of a local ale and porter merchant charged with putting false Bass labels on his products.17 In each of these cases Bass & Co. successfully pursued legal action against the individuals that had attempted to use the Bass logo. The company also placed adverts in newspapers warning customers to be wary of false labelling on products claiming to be Bass Pale Ale and recommended that customers deface the labels on empty bottles to prevent them from being refilled with ‘inferior’ ale.18 By making such a public spectacle of protecting the brand image, the company not only dissuaded fraudulent activity but more importantly, it sent out a clear message to consumers that Bass was a reputable company selling high-quality products that were worth protecting. Although tracking down and prosecuting fraudsters may have been time-consuming and expensive, ultimately it enhanced the company image which in turn made the Bass brand even more exclusive and desirable.

Although the origins of the red triangle design are somewhat unclear, it grew to symbolise quality and authenticity. Some historical accounts state that a clerk at Bass & Co. created the red triangle design in 1855.19 The reasoning behind the design is less clear. The Bass company scrapbook contained an amusing clip from The Westminster Gazette in 1894, which claimed that

Everybody knows the red pyramid pale ale label surrounded by a Staffordshire knot. It was the design of Mr George Curzon, one of the employees in the London agency and was first used in 1855. Some years ago an ingenious writer in one of the Sheffield papers wittily invented a classical legend about this label … the pyramid builders worshipped a great power called by some Tammuz, by others Bassareus, the son of the goddess Ops. He was termed Bassareus the fortifier …20

It is perhaps more likely that the triangle design represented the three key elements in Bass & Co.—namely, Bass, Ratcliff and Gretton or that the company realized the potential to reach consumers by using a simple bold geometric design on product labelling. In any case, a distinct brand image ensured that Bass products were visible during a period of intense competition in the foreign and domestic markets for beer. As Table 6.1 shows, the company spent increasing amounts on product labelling and advertising around the turn of the century.

By 1904, the advertising budget had grown in line with the company profit from sales, which increased from £3,102,479 in 1895 to £3,642,377 in 1904.21 At this time the company had an extensive system of agencies in various cities around the UK and the world. Between 1902 and 1903, sales increases were reported in Bristol, Nottingham, Glasgow, Belfast, Plymouth, Exeter, New York and Paris.22 Indeed, by the late nineteenth century, Bass Pale Ale had even penetrated Parisian bohemian culture. Edouard Manet’s impressionist painting from 1882 features bottles of Bass No. 1 Pale Ale on prominent display on the bar of the Folies-Bergere, which was one of Paris’ top music hall venues frequented by Manet and other artists.

Although Bass had cultivated a market for its products in Paris, the sales book for 1902–1903 also noted a marked decrease in sales in London and Newcastle. Between 1903 and 1905 profits from sales also dropped from £3,866,320 to £3,481,131.24 This decline in domestic sales followed the passing of The 1902 Licensing Act which imposed restrictions on the granting of new pub licenses. Since Bass had an extensive network of tied houses and had paid loans to many pubs, hotels and railway hotels across England, the decline in domestic sales and profits could be partly attributed to the change in legislation. It would, therefore, have been important to generate new sales and a key way to reach consumers was through advertising.

Bass had already established a strong brand image through product labelling and by the turn of the century, the company had built a reputation for selling high-quality beers and ales. Dwindling sales meant that in order to reach more consumers it was necessary to ‘invent’ new reasons for drinking Bass products and to sell these ideas to consumers—in essence, give people more reasons to drink Bass products. In order to be commercially successful, these reasons had to reflect cultural values and ideally reinforce them. One example was an advert from 1911 which depicted Bass’s ‘world-famed’ pale ale as ‘The Drink of the Empire’ with its path to success from 1778 to 1911 closely mirroring the expansion and dominance of the British empire. Whether intentional or not, there certainly seemed to be some truth in this advert. In the eighteenth century, pale (or October) ale was the drink favoured by the landed gentry, colonists and military elites. It was a socially desirable drink before it was exported to the colonies and became IPA. The conflation of ideas about social class and British imperialism was already part of the appeal of the drink. All Bass had to do was market those ideas.

Bass advertising also drew upon on other aspects of British culture such as the practice of ‘having a nip’ of alcohol to keep out the cold winter weather or to ‘ward off chills’. Bass ale was promoted as ‘the best winter drink’ because it contained ‘nourishing’ qualities which were not found in spirits. These adverts had a twofold purpose: to promote the idea that beer had health-giving properties and to persuade consumers that more expensive beers, like Bass, were especially therapeutic. It was important that consumers viewed beer as a viable alternative to the ‘pick-me-up’ offered by tonic wines and cheap spirits. Bass ales, although more expensive, had a reputation as medicinal alcoholic drinks that were prescribed by the medical profession.

In 1852, several articles on the chemical composition of Burton ales appeared in The Lancet . These followed reports from a chemist in France, that British bitter ales contained quantities of strychnine. As the reports were circulated in the British press, Allsopp and Bass grew concerned and asked The Lancet to conduct chemical analyses of their beers and to publish the results in the journal. It is clear from the extract of the report shown below that The Lancet undertook the task of analysing the beers not only because the medical profession prescribed (and perhaps drank) Burton ales but also because the French dared to attack the British national drink.

In all those countries in which the vine tree is extensively cultivated, wine is the ordinary beverage of the population; while in England the climate being unsuited to the growth of the vine, beer is the national beverage and enters into daily consumption of all classes of persons, from the richest to the poorest. It is therefore not extraordinary that any statement calculated to throw a suspicion on the genuine character of beer, should be viewed with alarm by the public and with the utmost concern by those engaged in the manufacture, whose pecuniary interests are of course largely involved.25

The reports provided very favourable analyses of Bass pale ale and IPA and refuted any claims that ‘British beers’ contained strychnine. Indeed, the reports also did a very good job of advertising the therapeutic qualities of Bass products

From the pure and wholesome nature of the ingredients employed, the moderate proportion of alcohol present and the very considerable quantity of aromatic anodyne bitter derived from the hops contained in these beers, they tend to preserve the tone and rigour of the stomach and conduce the restoration of the health of that organ when in a state of weakness or debility … it is very satisfactory to find that a beverage of such general consumption is entirely free from any kind of impurity.26

Although these reports appeared before the height of medical temperance later in the century when the medical profession shied away from such unreserved endorsements of the medicinal qualities of alcohol, they do highlight one of the key ways in which Bass ales came to be regarded as ‘wholesome’ national drinks. Half a century later, Bass marketed ‘barley wine’ (which was in fact a high gravity heavily malted beer) as a ‘wholesome’ medicinal winter drink. One advert for barley wine used another report from The Lancet which once again analysed the chemical composition of a Bass product and found that it possessed ‘a decidedly nourishing value’ compared to other strong beers and stouts.27 This medical endorsement would undoubtedly have helped Bass to market a higher alcohol beer as a viable alternative to other popular ‘medicinal’ drinks like invalid stouts, tonic wines and of course spirits like brandy and whisky.

By the turn of the century, Bass was one of many companies competing in the growing domestic market for alcoholic ‘health’ drinks and many of the adverts from the 1890–1910 period drew upon concepts of beer as a nutritious medicinal drink that could be used in a variety of situations for an array of health complaints. One advertising campaign used the miseries of the daily grind to convince consumers that Bass ale could help cure their ills. These adverts posed questions such as: ‘Can’t eat? Can’t sleep?’ and ‘Too tired to sleep?’ or ‘Tired or run down?’—and in every case the answer to the problem was to be found in a ‘nutritious’ glass of Bass ale. Another way to reach consumers was to market products for home consumption. This was undoubtedly a wise move during a period when restrictive licensing, limited pub opening hours and moral judgments made the trip to the local pub difficult or impossible for certain groups, most notably women.

By the early twentieth century, dwindling sales meant that it was important to reach and indeed create new groups of consumers whose custom and loyalty demanded more than a strong brand image. Creating and securing this market meant giving people ‘good reasons’ to drink Bass products—for health; to combat the daily grind of work or to cope with the worst of the British weather. Perhaps, people already drank beer for these reasons and all that Bass had to do was market these uses and sell the idea that Bass products were a cure-all for illness or an antidote to the stresses and strains of modern life. Intoxication was not marketed as a ‘good reason’ to drink Bass beer; in fact, the advertising was designed to draw consumers away from the very notion of intoxication—why drink to get drunk when there were so many other reasons to drink beer? Jean Baudrillard considers the manufacturing of needs and desires through the practices of marketing and advertising and argues that ideas about commodities are often unrelated to their primary function.28 In this sense, commodities communicate particular ideas about a society by creating and reinforcing cultural values. Alcohol acts as an intoxicant but the state of intoxication (drunkenness) was socially undesirable and therefore, it was necessary to market alcohol as a sign of something else: health; wellbeing; sociability; Britishness—or perhaps wealth, status and privilege. When King Edward VII visited the Bass site in 1902, the company seized upon the opportunity to publicise the event by marketing a special brew called ‘King’s Ale’ which was also known as ‘Bass No. 1 Strong Ale’. This kind of elite endorsement was something that drove the fortunes of another major alcohol producer in the late Victorian period, James Buchanan & Co. Ltd.

Making Scotch Respectable: Buchanan and Walker

This part examines the motives of distillers with case studies of two whisky producers, Buchanan and Walker who successfully cultivated a market for Scotch whisky in England. James Buchanan ensured that his company’s brands of blended whisky were conspicuously consumed by the British elites through the contract to supply to the Houses of Parliament and by securing Royal warrants. The chapter analyses the marketing strategies of both companies which, in different ways, promoted the idea that Scotch was a respectable and desirable alcoholic drink.

Many were aware of whisky’s shortcomings and idiosyncrasies. Grain whiskies were smooth but dull. Malts had flavour and charisma, but varied from batch to batch. The solution was blended whisky which combined grain and malt and ironed out their inconsistencies to give a consistently good drink.29

The trade in blended whisky expanded in the second half of the nineteenth century. This was the period of the so-called ‘whisky tide’ when Scotch whisky became a popular drink south of the border. Spiller believes that the popularity of Scotch whisky is linked to Walter Scott romanticism, the growth in Highland tourism and the grouse season attracting high society.30 The idea of a good Scotch was appealing but as the quote above suggests, the quality and taste of single malt or grain whiskies varied. Several key events led to the growth and development of the trade in blended whisky in the second half of the nineteenth century. The spread of the railway system in the 1850s had opened up the English market to Scottish products more generally.31 The trade in whisky expanded after the passing of The 1860 Spirits Act which allowed the blending of spirits in bonded warehouses without the payment of duty. The initial purpose of whisky blending was to reduce the cost of pure malt by mixing it with cheaper grain spirit made using the patent still method. In 1865, The Scotch Distillers Association was formed through an amalgamation of six major distillers looking to secure the future of their businesses by regulating the price and output of grain whisky.32 As Ronald Weir notes, between 1870 and 1914, distillers operated in a highly competitive free trade environment.33 In 1870, the total output of home-produced spirits was 24.4 million proof gallons (mpg) and this rose in 1900 to a total output of 42.8 mpg.34

These events occurred around the same time as the Phylloxera plant disease wiped out an estimated one-third to a half of French vineyards. This impacted upon the availability of brandy in England and thus created a niche in the market for the sale of whisky. Brandy was the preferred drink of the middle-and upper-classes and therefore in order to fill the gap in the brandy market, whisky had to be marketed as a suitable replacement and had to appeal to the tastes of English consumers. Spanish sherry was another popular drink in the nineteenth century and it was common for empty sherry barrels to be used by distillers to mature whisky. Consequently, the whisky matured in sherry barrels tasted like brandy.35 By the 1890s, there was large-scale production of blended whiskies in Scotland which led to increased competition in both the domestic and foreign markets for whisky. Successful companies like Buchanan, Dewar and Walker (known as ‘the big three’) made their fortunes from the production and sale of blended whiskies that were developed primarily for the English market. The success of these products rested in part on the skill of blenders to create Scotch that suited the English palate and also on the ability of companies to market scotch as a viable alternative to brandy that would appeal to the middle-and upper-classes.

The transformation of an ordinary commodity like blended whisky into Scotch, which became a status drink among the social elites, involved targeting specific groups of consumers and selling them particular ideas about the substance and James Buchanan did this very successfully. When Buchanan (who became Lord Woolavington) died in 1935, the Daily Express ran his obituary with the headline: ‘The secret that made Lord Woolavington: He found the formula for making England like Scotch Whisky.’ The article went on to report that Lord Woolavington had the reputation of being the wealthiest of the great whisky distillers of modern times. He started work as a clerk and the secret of his success was he found a formula for making Scotch whisky that was palatable to Englishmen.36 James Buchanan (1849–1935) began life as the son of a Scottish farmer and ended it as Baron Woolavington—businessman, entrepreneur, philanthropist and multimillionaire. Buchanan was an astute businessman, an opportunist and a risk taker—some of the key characteristics that defined the ideals of British imperial masculinity.

In 1879, Buchanan left his employment in the grain trade in Glasgow and moved to London to work for a whisky firm. By 1884, he had accumulated enough knowledge and contacts in the whisky trade to start his own business.37 As the retail side of the business grew, Buchanan began a process of backward integration to control the entire whisky manufacturing process through the purchase and control of distillers and bottling plants and in 1903 the company was registered as a limited company.38 Ronald Weir believes that the success of Buchanan’s early business strategy was down to his determination to climb the social ladder and seek prestigious clients and outlets for his products.39 Buchanan was adept at selling his whisky in desirable places and to influential people. He doggedly pursued contracts and quickly managed to get his blend of whisky sold in London hotels, theatres and other prominent drinking venues. As Spiller notes, the House of Commons contract in 1885 was a significant coup that highlights two key features of Buchanan’s sales strategy: one was exploiting opportunities and the second was promoting the brand.40

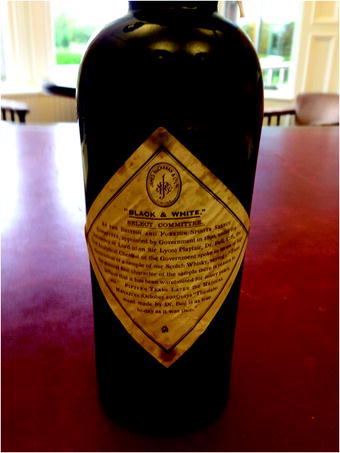

The 1890 Select Committee on British and Foreign Spirits asked an analytical chemist, Dr Bell, to test the whisky sold in the Houses of Parliament which was, of course, Buchanan’s blend (see Appendix for more detail on Dr Bell’s whisky test). This whisky test was seemingly conducted in order to aid the committee’s deliberations over the correct labelling of spirits and to establish if products should state the country of origin. The Committee was particularly keen to gather scientific data and opinions on the differences between blended whiskies and malt whiskies, and on the purity and strength of whisky and other spirits. The House of Commons whisky brand fared well from Dr Bell’s chemical analysis and Buchanan wasted no time in promoting the Committee’s findings through bottle labelling (see Figs. 7.1, 7.2, and 7.3) Buchanan used bottle labelling as the chief way to cultivate an elite status for his brands of whisky and no opportunity was missed to convince people that Buchanan’s whisky was the favoured drink of the social elites.

Buchanan secured royal warrants from Queen Victoria in 1898 and further royal warrants followed in 1901 from Edward VII and in 1910 from George V. This led to the marketing of the ‘Royal Household’ brand of whiskies which filled the gap left when the decision was taken in 1904 to officially change the ‘House of Commons’ brand to ‘Black and White’. Although the supply to the House of Commons still appeared on labelling after this date, it was less blatant until it was finally removed in 1915. In most historical accounts the reason given for this change is that due to the design of the bottle customers began asking for ‘that black and white whisky’ (see Fig. 7.1). This suggests that the company were responsive to consumer feedback and demands and were therefore willing to cast aside social emulation in favour of more straightforward marketing tactics. This may have been true but it is not the only reason why the House of Commons branding was eventually withdrawn. The records of the House of Commons Kitchen Committee in conjunction with Buchanan’s personal correspondence reveal the controversial nature of the company’s marketing strategy and the determination to pursue it.

When Buchanan secured the contract to supply the Houses of Parliament in 1885 he saw the advertising potential of this deal. The words ‘as specially selected for the House of Commons’ appeared along with pictures of the Houses of Parliament on the labels of Buchanan’s blended whiskies. Companies that supplied goods to the royal family also used this style of advertising on their products and therefore it must have seemed logical to promote the contract with the Houses of Parliament. However, the House of Commons Kitchen Committee which was responsible for the purchase and sale of alcoholic drinks within Parliament appeared to take exception to Buchanan’s marketing tactics and in 1895 the order to supply whisky went to another firm. In November 1895 Buchanan wrote a letter to W. Tudor Howell MP, an acquaintance who had recently been elected to parliament, complaining that his contract to supply whisky to the House of Commons had not been renewed

I supplied Messrs.’ Alexander Gordon & Co. Refreshment Contractors to the House of Commons with Scotch whisky, from December 1885 until the time when the House took the Refreshment Department under its own control. After this I continued to supply Scotch Whisky to the House and in December 1886, I was officially notified by the Kitchen Committee, that I was appointed supplier of Scotch Whisky to the Kitchen Department. Indeed, up to April 1893, I had practically the entire supply in my hands. Never at any time was there complaint … At the opening of the House in February 1893, I did not receive the customary order to supply. I called upon Mr Saunders, the Caterer, to ascertain the cause of this, as there had not been one word of complaint and no communication of any kind from the Committee. Mr Saunders informed me that the Committee had expressed displeasure at my making use, as an advertisement, of the fact that I supplied the House of Commons with Scotch Whisky.42

The letter went on to say that Buchanan believed that he had ‘only done what any other firm would do’ and used the examples of firms advertising the supply of goods to the royal household. He also pointed out that his replacement (another whisky supplier Messrs.’ Denman & Co.) were now using the House of Commons supply as a form of advertisement on bottles and business cards and he, therefore, felt that he had been particularly targeted

But the great injustice to me is this. My whisky, which has all along been associated with the House of Commons, is understood by the public generally, and asked for as ‘The House of Commons Blend’. The Trade now know that I do not supply the House, and this cessation of custom is doing me harm, as it is naturally assumed that my whisky has been dropped for good cause.43

Although there was no further correspondence to or from Mr Howell about this matter, presumably the letter had some effect because by 1901 Buchanan was once again supplying the Houses of Parliament with whisky. Labels on Buchanan Blend whisky from 1896 featured an extract from a letter sent by the manager of the Refreshment Department in the House of Commons, which confirmed that Buchanan had secured the order to supply whisky to the department ‘until further notice.’44 Other labels stated ‘The Buchanan Blend, Special quality fine old Scotch whisky as supplied to The House of Commons’ or ‘As supplied to The House of Lords.’45 So despite losing and then regaining the contract, Buchanan calculated that the benefits of advertising outweighed the risks. The success of Buchanan Blend rested upon its reputation as an elite drink and it was, therefore, vital to ensure continued consumer confidence in the product.

The records of the Kitchen Committee reveal that they remained displeased with the use of the contract as a form of advertising. In the committee meetings of June 1901, there were discussions of sourcing other whisky firms to fill the newly installed whisky vat.46 However, in July, it was resolved that the whisky vat should be filled ‘on this occasion’ with Buchanan’s blend and that Mr Buchanan should be informed that filling the vat in the House of Commons should not be used as an advertisement.47 Once again Buchanan chose to ignore this warning and carried on using the contract for advertising purposes. In 1905, the newly launched Black and White Blend labels included the statement ‘Black and White specially selected for the House of Commons.’48 Interestingly the Kitchen Committee, although clearly unhappy with the unwanted advertising, continued to order Buchanan’s whisky. In March 1909, the committee once again discussed changing whisky suppliers but agreed to go with Buchanan. It is not clear from the records whether this was a financial decision or one based upon a preference for the whisky. In March 1912, it was again resolved to order Buchanan’s whisky but noted that Mr Buchanan ‘should be told to stop using this contract for advertising and trading purposes.’49 However it took three years for Buchanan to take any notice and in 1915 all reference to the House of Commons was removed from labelling and from then on—until the 1990s in fact, the House of Commons brand was not sold to the general public but only within parliament. The timing of the move may have had something to do with the wartime restrictions on alcohol and it may have seemed inappropriate to draw attention to alcohol consumption within parliament. Yet Buchanan’s reluctance to bend to the will of the Kitchen Committee any sooner is understandable: The company had staked its reputation on the supply of products to the highest institutions in the country and used advertising as a means of cultivating and promoting the idea that Scotch was a respectable drink. By 1915, these objectives had been achieved and therefore removing the House of Commons branding but maintaining the supply was a logical concession.

Buchanan & Co. invested time and money in formulating and implementing many other advertising strategies besides bottle labelling. By the turn of the century, the company was already a visible presence in London due to its delivery horse and carts, which were distinctive because all the horses were of the same breed, and were well trained and groomed. The drivers were smartly dressed and the vans were highly polished and clearly showed the Buchanan company name. By this time the company had developed a range of different whisky brands which varied in terms of price, age and strength. In 1897 Buchanan wrote to an old acquaintance in Kilmarnock, who was a master blender, to ask for advice on developing a cheaper brand of whisky ‘I am anxious to get as successful a result as I can, and I am very desirous of getting the order, which will be large; but unfortunately it will be principally entirely a matter of price.’50 In the 1890s when alcohol sales were falling, it was important to promote cheaper products in order to broaden and develop the domestic market. The company began using the trade press for advertising and between 1897 and 1898 adverts appeared in periodicals with a picture of Buchanan Blend along with a quote from The Lancet which stated ‘Our analysis shows this to be a remarkably pure spirit and therefore well adapted for medicinally dietetic purposes’. The main advert heading stated ‘Ordered by MPs and Doctors’. Adverts also appeared in illustrated weekly newspapers and provincial newspapers.51

Between 1904 and 1910 the subject of advertising was a constant theme raised at company board meetings. Buchanan sought to expand the business in England and Scotland and one of the most promising ways to do so was through the use of railway advertising and the sale of whisky in railway refreshment rooms, buffet cars and hotels. In September 1906, it was agreed that advertising show cards should be placed in North Eastern Railway refreshment rooms. It was resolved to increase advertising costs to one pound per show card per annum for not more than 30 show cards.52 Over the next few years, the committee also agreed to place posters and show cards in the Midland, Great Northern Railway, London and South Western Railway, G&R and Bakerloo railway lines. It was proposed that the posters displayed in refreshment rooms and stations featured ‘Morning Nip’ advertisements, presumably encouraging consumers to drink Buchanan’s whisky on the morning commute to work. Between 1908 and 1909 there were discussions of expanding advertising to the Eastern counties and Scotland and it was decided to place posters in the principle railway stations in Scotland and to accept advertising space at Glasgow Central Station for £100 per year. It was also agreed to place posters at various other Scottish railway stations and to pay 12 guineas to Highland Railway for stocking Buchanan’s whisky for sale in buffet cars and in hotels. In addition, the committee agreed to advertise in Liverpool and surrounding stations to the total of 100 posters.53

Other advertising strategies were discussed such as theatre and hotel advertising but only certain ‘high class’ venues such as The Ritz hotel and The Lyric Theatre were deemed suitable. At one board meeting in February 1908, the subject of playing cards cropped up. The company had received letters from customers and others suggesting playing card advertising for the home trade but the suggestion was unanimously dismissed. This seems strange because the company had been reaching out to a broader range of consumers through newspaper and railway advertising, which suggests a strategy of selling products to consumers of all social classes but perhaps the association of playing cards with gambling was viewed as undesirable.

After 1910, the company developed the Black and White brand advertising which used the concept of ‘black and white’ to symbolise the ideals of British imperialism. The adverts initially featured two dogs: one a West Highland terrier and the other a Scottish terrier—one black and one white. The dogs had ‘character’ and breeding and they were distinctive because of their colours, which were contrasting and oppositional. Yet despite their differences the dogs always stood together, side by side, sometimes fighting a common enemy. For example, an advert from 1909 (Fig. 7.4) showed the two dogs sitting side by side with the caption ‘Still Watchers’ while another advert from 1910 featured the black and white dogs chained together chasing a rat and a cat.54 The advertising also drew upon other ‘black and white’ themes such as the black and white women advert from 1909 (Fig. 7.5), which showed a ‘black’ woman walking behind a young ‘white’ woman in a manner suggesting a colonial mistress and maid relationship. Like the dog adverts, the concept of black and white represented a contrasting but seemingly complimentary relationship—there could not be one without the other; the white needed the black and vice versa; the colours represented a ‘good blend’ like the Scotch.

Of course, Buchanan was not the only company to commodify British imperialism. An advert for Four Crown Scotch Whisky that appeared in the trade journal The National Guardian in September 1900 ran with the caption ‘A Powerful Peacemaker’ and showed a sketch of soldiers and prisoners in an army camp during the Boer War, sharing glasses of whisky. Beneath this scene the advert claimed

While a prisoner of war in Pretoria, The Earl of Rosslyn, in a letter to the London Daily Mail of 11th July 1900 shows, how as soon as the news of Lord Roberts’ approach reached the town almost everyone went wild with excitement. He says – “Hollander and Britisher, soldier and Boer peasant, prisoner and warder, joined in a mutual expression of esteem and a glass of Robert Brown’s Four Crown Scotch Whisky.

By 1900 Scotch was an imperial drink. Companies like Buchanan, Dewar and Walker had built up large export markets using imperial trade links. By this time Buchanan sold products in Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa, Jamaica, South America, North Africa, Canada and the United States. An advert for Walker’s whisky from 1910 showed an image of the famous ‘Johnnie Walker striding man’ with the caption

Born in 1820 and still going strong – so when someone out in Calcutta or Borneo or Cape Town or Sydney or Valparaiso or any other little jaunt from ‘home’ laments that he cannot get the good old Scotch they have at ‘home’, call for Johnnie Walker, let him taste it, and tell him about the vast ageing reserve stock and the ninety years experience that make possible the guarantee.55

By 1910, Walker had developed the ‘Johnnie Walker striding man’ character, which was distinctive and resembled a rather (by that time) antiquated nineteenth-century upper-class dandy. In the adverts, the striding man was ‘going strong since 1820’ because this was the year when the company first began trading as a licensed grocer in Kilmarnock, Scotland. Like Buchanan, Walker also believed in the power of advertising and of creating a brand image that both promoted and reflected the ideals of British culture and imperialism. In the 1911 ‘Fashions come and go’ campaign, the striding man was inserted into a variety of settings which depicted him as a gentlemanly protector. The adverts showed scenes of Johnnie Walker helping well-to-do ladies step over puddles; shielding them from rain and high winds and ‘helping’ ladies play a game of croquet.56 These adverts drew upon concepts of class and gender in order to sell ideas about whisky to middle-class women who were the group most likely to buy Scotch from licensed grocers. The adverts promoted the idea that Johnnie Walker’s whisky embodied the ideals of respectable masculinity—and therefore Scotch was a man’s drink but it would certainly ‘help’ if ladies knew which brand to choose.

The success of companies like Buchanan and Walker lay in the ability to cultivate and expand the domestic and foreign markets for blended Scotch whisky. In Scotland, blended whisky was commonly drunk by the working classes because it was cheap and often bad—either watered down or adulterated with other intoxicants. The better quality blended ‘Highland’ whiskies were often produced in or around the central belt near Glasgow or Edinburgh and were subject to ‘Scotch myths’ marketing in order to boost sales. James Buchanan went further to completely reinvent blended whisky as a desirable and respectable drink of the British elites. His dogged pursuit of advertising via product labelling ensured that Buchanan whisky became firmly associated with ideas about quality, taste and privilege. The Johnnie Walker striding man is another example of product marketing designed to elevate the status of whisky and to Anglicise it—making it conceptually palatable for the English market. Both companies knew that the use value of whisky as an intoxicant held little currency compared to its cultural value and more specifically, it’s potential as a source of cultural capital. Advertising played a key role in this process because it was vital to generate and maintain consumer interest, confidence and loyalty. The economic value of alcohol—in terms of expanding the drink trade and generating tax revenue—was largely dependent upon maintaining and developing the cultural value of the substance. If the cultural value evaporated amid a climate of temperance campaigning and legislative controls then there could be no market for alcohol. Therefore, the best way to keep people drinking was to sell them ideas about drinks that veered away from alcohol’s primary effect of intoxication and instead promoted contemporary social values. However, as the Gilbey records show, by the turn of the century, maintaining the market for alcohol became more complex as consumers were increasingly drawn towards particular brands of alcoholic drinks that they associated with ideas about quality and taste.

Selling the ‘Illusion’ of the Brand: W & A Gilbey

This part considers the alcohol retail trade with a case study of one of the leading wine and spirit merchants in the Victorian period, W & A Gilbey, which restructured its business model due to pressure from customers to supply branded products. In the late Victorian period, particular brands of wine, champagne and spirits became more popular because they were associated with ideas about quality and taste. The company realised that in an emerging consumer culture, the power or ‘illusion’ of the brand held great commercial profit.

There are indeed many people who want to buy limited quantities of the best brandy than of the best champagne, as it is looked upon somewhat as a medicine that must be kept in the house, and it is just as difficult to get them to believe this can be obtained without the brand of Hennessey or Moet, as the finest champagne can be obtained under W&A Gilbey’s Castle 4a or Castle 5a. We shall therefore, make just as large a profit on any goods we sell under these brands as if we sold them under the brand of W&A Gilbey, and shall thereby meet the wants and prejudices of two classes of consumers, and at the same time reap equal advantages both present and future out of either.57

W & A Gilbey began business in the wine and spirit trade in the 1850s as a family company run by three brothers, Walter, Alfred and Henry along with other male family members. The business expanded after the 1860 Licensing Act which led to the growth in the off-licence trade. The company appointed sales agents in most principle cities in Britain in order to stimulate and secure business with licensed grocers. Gilbey’s interests lay principally in the retail side of the trade and the company bought wines and spirits which they either sold directly on to customers or bottled and labelled as their own brand of goods. However, as the quote above indicates, the demand for branded goods increased towards the end of the century and the company was forced to restructure its business model in order to meet customer demand and secure the market for its products.

The company produced a price list in 1896 that was designed to promote its market position as the leading retailer of wines and spirits. It claimed that during 1895 every 14th bottle of wine and every 35th bottle of spirits consumed in Britain had been sold by W & A Gilbey.58 The price lists from 1870 to 1896 featured a broad range of wines, spirits and beers that were purchased and then rebranded under Gilbey’s ‘Castle’ brand name. The Castle branding was given to a range of drinks, such as brandy, gin, whisky, sherry, port, liqueurs, champagnes and wines. The price lists were extensive and contained detailed information on the types of drinks, their origin, strength, qualities and uses. Although the Castle brand dominated the price lists, by 1890, sales agents reported complaints from customers who wanted particular brands of wine and spirits that Gilbey did not supply. The company was therefore forced to rethink its position on the supply of branded goods.

There was a realisation that in order to compete in a changing market for alcohol, the company would have to give customers what they wanted—which was the ‘illusion’ cast by particular brand names which conferred ideas about quality, taste and status. The committee agreed to expand the sale of branded goods and decided to deal with five prominent wine houses: Croft & Co., Silva & Cosens (Dow), Gonzales Byass & Co., Ingham Whitaker and Cossart Gordon & Co.59 It was also agreed to provisionally deal with Burgoyne & Co. for the supply of Australian wines because it was noted that ‘the introduction of Australian Wines has afforded us an insight of the power of certain brands over the public, and the additional customers that our agents have secured for them.’60 The committee also discussed the purchase of wine that had been rebranded under the Castle label which simply listed the type of wine, for example sauvignon etc. It was noted that

It is a very fortunate thing for us that a knowledge of brands on the part of the public have only gone as far as champagne and brandy, which has naturally been owing to their having been bottled abroad, when the shippers have been enabled to place their name before the public rather than the wine merchant on this side. The reputation of champagne is entirely owing to the fact that the wine must be bottled in the place of production … It would however be impossible to make one name famous alike for ports, sherries, whiskies, brandies and W&A Gilbey never can hope to do so. They can, however, easily make themselves famous for supplying the finest brands of every country and it is important that they should lose no time in endeavouring to make the names of the Houses they have allied themselves with equally famous to the public as they now are to the trade before attempts are made to supply the public with other.61

By selling brands that would in essence compete with their own brand of goods, the company believed it would secure its position in the market because it could promote its own goods alongside others. In the 1860s, the company had entered into a contract with John Jameson & Sons to purchase large quantities of whisky from Jameson’s Irish distillery. The whisky was held in bonded warehouses in Dublin and then marketed under the Gilbey brand name ‘Castle Grand JJ’. This branding partnership had been successful in securing sales of Jameson’s whisky until the 1890s when Scotch whisky captured the market position previously held by Irish whisky. By 1890, it was felt that rebranding Jameson’s whisky would help boost sales and therefore all reference to W & A Gilbey was removed from the labelling. However, this clearly did not remedy the situation and in 1897 the committee produced a report, which included an interview with Jameson himself. The report stated that

He [Jameson] referred to the decline in England in the consumption of Irish, compared with the great strides made in Scotch whisky. He remarked in a jocular way “we are not going to give up the game yet, but want to do all we can to popularise Dublin whisky in England, and we think you can help us.”62

Jameson suggested that Gilbey’s sales agents ask grocers to display show cards for JJ whisky alongside any adverts for Scotch. Jameson did not want to advertise his products in any other way and refused advertising in railway stations but preferred adverts in grocers at the point of sale. He was told that it was not within the company’s power to compel customers to advertise Jameson’s whisky. Jameson pointed out that their mutual arrangement and success depended on the continued trade in Irish whisky in England and that in Ireland he could ‘run alone’ but needed help to sell his goods in England.63 However, the committee felt that they could only go so far in promoting Jameson’s whisky and if sales in Irish whisky in England were declining then the company’s focus should instead be placed on the marketing of Scotch.

Rebranding Castle Grand JJ had not halted declining sales in Irish whisky but the committee still believed that removing the W & A Gilbey name from Jameson’s whisky and their own Glen Spey Scotch would improve brand confidence. The 1897 committee report effectively recommended the removal of the Gilbey name from all but the cheapest brands.64 The logic for this was based on an analysis of sales which identified four types of consumers: First, there were those who wanted to buy the cheapest products if they were known to be genuine; Second were those who wanted a ‘fair medium price article.’; Third were consumers who wanted the finest quality products regardless of name or brand; Fourth were those who wanted the best brand regardless of quality. The report went on to state that

The public cannot be brought to feel that W&A Gilbey with all their advantages of wealth and commercial knowledge which they give them credit for, possess the same opportunities of buying ports and sherries or Marsala and Madeiras as Croft and Dow or Gonzales, Crossart and Ingham. They imagine these brands are connected with the production of certain favoured vineyards and form monopolies of these Houses … If during the last few years we have increased our reputation for selling pure but cheap wine, we have also considerably increased our commercial reputation and the public are disposed to place unbounded confidence in us when we state that Croft’s Port and Gonzales Sherry are the finest, but are very loathe to believe us when we endeavour to crack open our own goods such as Castle J Port and Castle A Sherry, no matter what the quality may be. … The whole of our success is to be traced to names, brands, vintages etc. which by degrees we have added to our price list.65

From the analysis of consumers and based on the information from sales agents, the company had decided that the Castle label could only fill a certain niche in the market. By the turn of the century, consumers wanted branded goods and therefore the company focus had to shift accordingly. When the business had taken off in the 1860s, Gilbey’s customers were less ‘brand driven’ and were content to buy many products from reputable wine and spirit merchants. By the turn of the century however, the company name and reputation could no longer be relied upon to generate sufficient alcohol sales because unbranded products could not be consumed conspicuously. Brand names of particular types of alcoholic drinks were well known—even the more expensive ones and sometimes the form of advertising was particularly innovative.

A good example of this was found in the music halls which emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century from pubs that offered entertainments.66 These places ranged from small ‘penny gaffs’ located in pubs to large venues such as theatres.67 By the turn of the century, music halls had grown in popularity by offering cheap entertainment to the urban working classes in cities across Britain.68 One of the most popular acts in the late Victorian period was a musical pastiche of upper-class men known as the ‘swell song’. Bailey describes a swell as ‘a lordly figure of resplendent dress and confident air whose exploits centered on drink and women.’69 The most famous (or indeed infamous) performer of the swell song was George Leybourne with his act ‘Champagne Charlie’. Leybourne’s theatrical success was built upon his sharp observations of the drinking habits of the rich, which was wrung out for a laugh to the appreciation of the music hall crowds. Leybourne wrote the lyrics for Champagne Charlie

The way I gained my title’s

By a hobby which I’ve got

Of never letting others pay

However long the shot

Whoever drinks at my expense

Are treated all the same

From Dukes to Lords to cabmen down

I make them drink champagne

From coffee and from supper rooms

From Poplar to Pall Mall

The girls on seeing me exclaim

“Oh what a champagne swell”!

The notion ‘tis of everyone

If ‘twere not for my name

And causing so much to be drunk

They’d never make champagne

Some epicures like Burgundy,

Hock, Claret and Moselle,

But Moet’ s vintage only

Satisfies this champagne swell

What matters if to bed I go

Dull head and muddled thick

A bottle in the morning

Sets me right then very quick

Chorus

For Champagne Charlie is my name

Champagne Charlie is my game

Good for any game at night, my boys

Good for any game at night, my boys

For Champagne Charlie is my name

Champagne Charlie is my game

Good for any game at night, my boys

Who’ll come and join me in the spree?70

The idea that Champagne Charlie kept the champagne industry in business through his prolific drinking bore some reality to the free supply of champagne gifted to Leybourne from London wine merchants in return for publicity.71 So it would seem that the reference to Moet was perhaps intentional. Although there is no evidence to suggest that Gilbey & Co. supplied champagne to Leybourne or any other music hall performer, the Champagne Charlie act demonstrates the ways in which ideas about particular brands of alcoholic drinks were propagated.

In the consumer society that emerged in the late nineteenth century, Veblen’s ideas about conspicuous consumption were evident. The Gilbey records show that customers were increasingly brand-driven, demanding particular types of wines, spirits and champagnes that could be consumed as markers of wealth, status or taste. The company knew that it was impossible to convince customers that its own-brand products were of an equal quality and therefore relegated only the cheapest products to the company branding. This in turn elevated the status of branded goods to those which were more expensive and therefore all the more exclusive and desirable. In this sense, the ‘illusion’ of the brand was a powerful and persuasive way to secure the market for alcohol.

Notes

- Wilson R. G. 1988. ‘The Changing Taste for Beer in Victorian Britain’, in (eds.) Wilson R. G. and Gourvish T. R. The Dynamics of the International Brewing Industry Since 1800: London: Routledge: p. 99.2.

- Ibid.: pp. 93–105.3.

- Ibid.4.

- Foster T. 1990. Pale Ale, U.S.: Brewers Publications: p. 11.5.

- Houghland J. E. 2014. ‘The Origins and Diaspora of the IPA’, in (eds.) Patterson M. and Hoalst-Pullen N. The Geography of Beer: Regions, Environment & Societies: New York: Springer: pp. 119–131.6.

- Ibid.7.

- Reinarz J. 2007. ‘Promoting the Pint: Ale and Advertising in Late Victorian and Edwardian England’: Social History of Alcohol and Drugs: Volume 22:1: p. 26.8.

- Owen C. 1992. The Greatest Brewery in the World: A History of Bass, Ratcliff and Gretton: Chesterfield: Derbyshire Record Society.9.

- Ibid.: pp. 77–78.10.

- Ibid.11.

- Ibid.: p. 27.12.

- Barnard A. 1889. Noted Breweries of Great Britain and Ireland Volume 1: London: Joseph Carlson & Sons: p. 46.13.

- Ibid.: p. 49.14.

- Ibid.: p. 117.15.

- National Brewery Archive (NBA), Bass & Co. Infringement Book 1870–1925.16.

- The Belfast Morning News: 3 March 1859.17.

- The Manchester Courier: 23 May 1886.18.

- Northern Whig: ‘Bass’s Pale Ale: Caution Notice’: 21 March 1863.19.

- Owen C. 1992. The Greatest Brewery in the World: A History of Bass, Ratcliff and Gretton: Chesterfield: Derbyshire Record Society; Barnard A. 1889. Noted Breweries of Great Britain and Ireland Volume 1: London: Joseph Carlson & Sons.20.

- NBA: M/5/33: Bass Scrapbook: The Westminster Gazette: 31 January 1894.21.

- NBA: Bass, Ratcliff & Gretton Ltd Balance Sheets: 1895–1904: Income from sales of ale, stout and sundry products.22.

- NBA: B1/18: Bass & Co. Ltd Comparative Agency Sales Book: 1902–1903.23.

- NBA: A/100: Bass, Ratcliff & Gretton Ltd, Balance Sheets: 1896–1904.24.

- NBA: Bass, Ratcliff & Gretton Ltd Balance Sheets: 1895–1914: Income from sales of ale, stout and sundry products.25.

- ‘Records of the Results of the Microscopical and Chemical Analyses of the Solids and Fluids Consumed by all Classes of the Public: The Bitter Beer, Pale Ale and India Pale Ale of Messrs Allsopp & Sons and Messrs Bass & Co of Burton Upon Trent’: The Lancet: Volume 59:1498: 15 May 1852: pp. 473–477.26.

- ‘Analyses of the Bitter Beer and Indian Pale Ales Brewed by Messrs Bass & Co.’: The Lancet: Volume 1:1498: 15 May 1852: pp. 478–479.27.

- An extract of the 1909 article is shown below on the product label.28.

- Baudrillard J. 1988. ‘Consumer Society’, in (ed.) Poster M. Selected Writings: Cambridge: Polity Press: pp. 29–56.

- Townsend B. 2011. Scotch Missed: Scotland’s Lost Distilleries: Glasgow: Neil Wilson Publishing Ltd: p. 31.2.

- Spiller B. 1984. The Chameleon’s Eye: James Buchanan & Company Limited 1884–1984: London and Glasgow: James Buchanan & Co. Ltd: p. 8.3.

- Ibid.: p. 9.4.

- Weir R. B. 1982. ‘Distilling and Agriculture’ in Agricultural History Review: pp. 49–62: www.bahs.org.uk/AGHR/ARTICLES/32nla4.pdf: accessed 4/11/2014.5.

- Ibid.6.

- Ibid.: p. 50.7.

- Townsend B. 2011: p. 30.8.

- ‘James Buchanan’s Obituary’: The Daily Express: 27 August 1935.9.

- Atherton F. W. 1931. History of House Buchanan: No Other Publication Details.10.

- Weir R. B. 1974. ‘The Distilling Industry in Scotland in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries’: PhD Dissertation: Edinburgh University: pp. 552–560.11.

- Ibid.12.

- Spiller B. 1984: p. 12.13.

- The label on the bottle states: At the British and Foreign Spirits Select Committee appointed by the government in 1890, under the presidency of Lord Playfair, Dr Bell, CB, the chief analytical chemist of the government spoke in terms of high appreciation of a sample of our Scotch whisky saying ‘From the general fine character of the sample there is reason to believe that it has been warehoused for many years etc.’ Fifteen years later the Medical Magazine (October 1905) says the statement made by Dr Bell is as true today as it was then.14.

- DA: Acc1033671: Buchanan’s Letter Book: 1888–1897: Letter to W. Tudor Howell Esq MP: Dated 9 November 1895.15.

- DA: Acc1033671: Buchanan’s Letter Book: 1888–1897: Letter to W. Tudor Howell Esq MP: Dated 9 November 1895.16.

- DA: Acc 125/3: Buchanan’s Label Book: 1896.17.

- DA: Acc 125/3: Buchanan’s Label Book: 1896.18.

- UK Parliamentary Archives (PA): House of Commons Kitchen Committee Records: HC/CL/CO/EA/2/2: Minute Books: 1901–1905.19.

- Ibid.20.

- DA: Acc 125/3: Buchanan’s Label Book: 1905.21.

- PA: House of Commons Kitchen Committee Records: HC/CL/CO/EA/2/3: 1906–1912.22.

- DA: Letter Book: Acc103367/(1/2): 1897–1902: Letter from James Buchanan to David Sneddon: Dated 28 December 1897.23.

- Spiller B. 1984: p. 34.24.

- DA: Acc 100045/1: Buchanan Minute Books: 1906.25.

- DA: Acc 100045/1: Buchanan Minute Books: 1906–1910.26.

- DA: 884/43: Buchanan Black and White Adverts: 1910–1911.27.

- DA: John Walker ‘Striding Man’ Advertising: 1908–1911.28.

- DA: John Walker ‘Striding Man’ Advertising: 1908–1911.

- Diageo Archives (DA): 100433/1: W & A Gilbey Committee Minutes: 1890.2.

- DA: 100422/190: W & A Gilbey Price Lists: 1870–1896.3.

- Ibid.4.

- DA: 100433/1: W & A Gilbey Committee Minutes: 1890.5.

- DA: 100433/1: W & A Gilbey Committee Minutes: 1890.6.

- DA: 100433/1: W & A Gilbey Committee Minutes: 1897.7.

- DA: 100433/1: W & A Gilbey Committee Minutes: 1897.8.

- DA: 100433/1: W & A Gilbey Committee Minutes: 1897.9.

- DA: 100433/1: W & A Gilbey Committee Minutes: 1897.10.

- Maloney P. 1993. Scotland and the Music Hall 1850–1914: Manchester: Manchester University Press: pp. 24–57.11.

- Bailey P. 2003. Popular Culture and Performance in the Victorian City: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: p. 100.12.

- Maloney: pp. 24–57.13.

- Bailey: p. 101.14.

- Ibid.: pp. 109–110.15.

- Ibid.

From Drinking in Victorian and Edwardian Britian, by Thora Hands (Palgrave MacMillan, 2018), published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.