The historical evolution of the great schism between Catholicism and Protestantism.

By Dr. Natalya Davidko

Assistant Professor of Business Management

Moscow Institute Touro

Introduction

Without Pity Heare Their Dying Grones.1

How dreadful knowledge of the truth can be When there’s no help in truth!2

Violence exists in many forms: physical and psychological, mob violence and individual violence, political and religious to mention but a few.3 More than seven hundred years ago, in 1314 in his unweathering masterpiece, The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Dante condemned violence as sin, and placed homicides and everyone who “smites wrongfully,” in the first round of the sixth circle. “By violence, death and grievous wounds are inflicted on one’s neighbor; and on his substance ruins, burnings, and harmful extortions.”4 In recent years, violence of all kinds has been on the rise among them religious violence takes pride of place, suffice it to mention Al-Qaeda or ISIS or religious clashes between Christians and Muslims, or Judaists and Islamists in many corners of the globe. Violent deaths, ranging from individual homicide to the genocide of entire nations have been our bane for generations.

Though many religions teach people to treat others with kindness, violent conflicts erupt continually, to which history bears witness. “Serious research shows that religiosity does not necessarily lead to a decrease but rather, at least in certain circumstances, to an increase in latent or manifest violence‛.5 Moreover, religions “tend to accept violence as an inevitable part of reality and even justify the use of violence on religious grounds”.6 Religious extremism is seen as one of the mega-problems of the 21st century, but it is not a new phenomenon: from the sixth century till well into the 18th century, it formed one of the biggest challenges that England (and Europe) faced and which took several centuries to resolve.

Christianity has a long history of religious violence going back to the first persecutions of the Church in the year AD 34, when St. Stephen was stoned to death on the charges of blasphemy. Under Nero (AD 67), emperor of Rome, thousands of Christians were killed. Nero personally contrived all manner of tortures. He set people on fire like live torches to illuminate his gardens, set wild animals on Christians to rip them to pieces, or boiled them in oil. In his reign, the Apostle Paul was beheaded, the Apostle Peter was crucified with his head down and his feet upward. During the Middle Ages, the Church demonstrated equal ferocity, the most notable examples are the Inquisition and the Crusades.

The current article is devoted to what we define as ‘politico-theological violence’, which smote several generations of bishops, priests, and laity of all walks of life in the history of English Christianity. Our special focus is on the historical evolution of the great schism between Catholicism and Protestantism (historical facts are important for the study of the genesis of Christian violence), whose aim was to combat the faith of the adversary. Sixteenth-century stereotypes and values differ dramatically from our modern humanitarian worldview. During this period, the political and social significance of violence was treated as a matter of critical importance. It was not regarded as violence as we understand it today, but a kind of higher piety and divine purification of evil. It was sanctified by the Church and legitimatized by the state.

Theoretical Premises

Conceptualization of the 16th-Century Violence

The issue of violence and its role in society (primitive or modern) has been drawing the interest of philosophers and artists, especially in relation to religion, be it paganism with its rituals of sacrifice or Christianity with its martyrdom, theology of the Cross or the punishment of impurity.

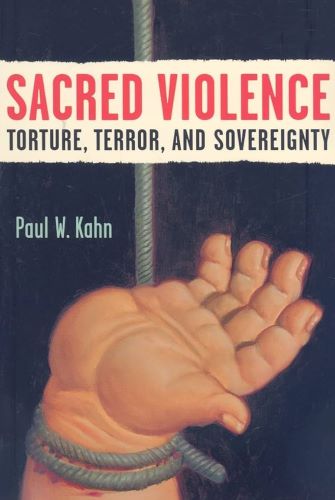

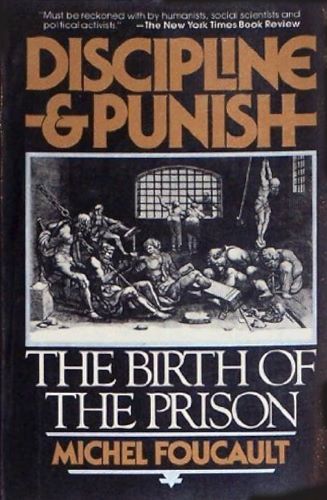

Modern philosophers belonging to different schools come up with theories explaining the use of violence drawing on rich historical experience. The current study is premised on the works of three philosophers, who addressed the issue of violence from different positions but arrived at similar conclusions. Michel Foucault in his work, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1979), analyzed historical changes in the French criminal justice system.7 René Girard, philosopher of social science and literary critic, in his book, Violence and the Sacred (1977), gives an encompassing view of causes of religious violence and shows how religion and violence are interlaced.8 Paul Kahn’s book, Sacred Violence: Torture, Terror, and Sovereignty (2008), focused on the analysis of torture and terror in the modern world, but contains insightful comments on the role of violence in pre-modern and early modern societies.

All the three researchers argue that violence has always been intricately connected with power and performed a political function of “emphatic affirmation of power and of its intrinsic superiority”.9 The objective of torture was confession, i.e., acknowledging sin – either against God or the sovereign. “Without acknowledgement of sin, the sovereign might exercise violence but not power”.10 Foucault summarizes, “If torture was so strongly embedded in legal practice, it was because it revealed truth and showed the operation of power”.11 In the history of penal law, torture originated in “investigative procedures that administered pain in the name of eliciting the truth of a crime and displaying its purgation”.12

Public executions were another inalienable element of violence. Foucault calls it “punishment-as-spectacle,” Kahn describes it as “the spectacle on the scaffold”. The aim was to instill terror in the subjects. The entire course of the death ceremony was meticulously elaborated; it was “the art of maintaining life in pain: gradation of pain was calculated so as to prolong the agony”.13 European sovereigns did not hesitate to use torture and believed its visible manifestations exalted and strengthened their omnipotence. In this “theatre of horror,” Foucault points out a constitutive role of spectators. Sometimes they took an active part in the bloody spectacle. “In their most elementary forms, these were shouts of encouragement or cheering that accompanied the condemned man to his execution, sometimes insults or mud-throwing”;14 often there were cries “Away with him!” or “Hang him, hang him!”

Several important conceptual categories in viewing violence were elaborated. Girard developed the concept of Sacred Violence, a sanctified, legitimate form of violence approved by the church and buttressed by the judicial system, directed at all enemies of the faith and state. He also explored the concept of scapegoat or the surrogate victim, through whom the “burden of sin” can be expiated and whose destruction was believed to purify society of all ills.15 Whether the victim is really guilty of the sin ascribed to it does not matter much. The mechanism of surrogate victim transposes the ultimate truth to the realm of the divine so that God’s truth is hidden from the common people and may be revealed to the select few. “The more detestable the victim was made to appear and the more passion he aroused, the more effectively the machinery functioned”.16 According to Girard, the surrogate victim is the basis for all religious systems. To make a guilty party amenable to punishment, religious thought has contrived an impressive “body of phenomena under the heading of impurity – phenomena that seem disparate and absurd” but under certain circumstances can well serve the cause.17 How can one cleanse the infected members of society of all traces of impurity? The answer is evident – by blood. “Only blood itself, the blood of sacrificial victims can accomplish this feat”.18 Gerard goes as far as to state that “There is a unity that underlies the whole of human culture, and this unity of unities depends on a single mechanism – the community’s unanimous outburst of opposition to the surrogate victim”.19

Another important element was “gallows speeches.” Foucault says that great importance was attached by the authority to the last words of the victim. “These last moments, when the guilty man no longer has anything to lose, are established as the moment of truth”.20 The condemned criminal was given an opportunity to speak, not to proclaim his innocence, but to acknowledge his crime and the justice of his conviction. These speeches were ranked as propaganda and moralization, so they were kept under strict ideological control. However, a convicted criminal might cause “disturbances around the scaffold” and become “a saint by not giving in under torture, and displaying a strength that no power had succeeded in bending”.21 Resistance to recantation became a sign of martyrdom.

Kahn comes to a conclusion that violence in society has often had a strong element of conflict between confessional faiths.22 Religion legitimizes the application of violence as a curative means, imbues it with holiness and represents it as higher justice.

Research Material

The analysis of research literature is of utmost importance for understanding the pulse beat of society; it is a reflection of the thoughts and emotions of people, their anxieties and aspirations. In addition, it performs ideological work and creates vehicles for promoting and propagating political views and theological doctrines espoused by temporal or ecclesiastical authorities. These are claimed to be ultimate truths, which help structure society’s world of meaning. The truths are historical, but not existential though efforts are undertaken to pass them off as such.

It is necessary to point out that the choice of research material is based on religion-oriented texts whose ‘leitmotif’ is violence and which express differing sentiments of members of society. In order to achieve fresh handling of the subject of violence, we didn’t want to take the beaten path and have chosen the authors who are partly unknown to the modern reader, partly forgotten, rarely read or considered second-rate. The material includes sermons, politico-theological writings, chronicles, Acts and ordinances issued by the Tudor sovereigns, laws, psalms, drama, and broadsides. An examination of pieces of literary texts proposes to reveal the ideological effort and appraise their propagandistic value. All citations are presented in the 16th century spelling. Historicity is the leading principle of the research.

Anglo-Saxon England Embraces Christianity

When Æthelbert, king of Kent (from 589 to 616), the most powerful realm in the Heptarchy, met the Roman missionary St. Augustine,23 he was so impressed by his personality that underwent baptism and brought Christianity into his realm. He understood that the new cultural system was badly in need of laws and rules to govern its activities. To this end, the already existing customary laws were remodeled to incorporate a new system of faith and its institutions into the existing social order. The importance of his laws is that they provide us with the earliest known written information about the social status of the Church codified in the legal system. “The very first sentence of his code, the first recorded utterance of English law, mentions churches, bishops, priests, deacons, clerks”.24 It is of interest to note that the clergy were higher to the king in terms of priority for protection and enjoyed “preeminence of social and legal status in Kentish AngloSaxon society”.25 Thus, starting from the 6th century AD, the underlying basic ideology of English life was Catholicism, Rome-style. Other cyninges followed suit. Ina (king of Wessex), Ceolwulf (king of Northumbria) adopted laws that separated the Church from secular institutions and proclaimed Christianity to be one faith in the land: ‚We are all to love, and worship one God, and strictly hold one Christianity, … one Christianity, and one kingship, forever in the nation”.26

Anglo-Saxon kings saw practical utility of Christianity for themselves in consolidating their power within their realms or, if possible, obtaining suzerainty over other kingdoms. Damian Tyler points out that “Early medieval Christianity presented an image of God as king of a hierarchically organized universe, an ideology that served to enhance the status of his earthly counterparts”.27 Moreover, Anglo-Saxon kings hoped that they would monopolize religion under their power in the hierarchical organization of the infant nation-states and that bishops would be utterly dependent on their favor, which was a great historical misapprehension that caused much bloodshed in the centuries to come.

Inspired by Bede’s28 ideas, King Alfred the Great, King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886 and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899, wrote books for the people of his time to read in their own tongue and defined the concept of the National church. First of all, he contended that “the English church which is still new in the faith must establish her own customs and engrain them in the minds of the English”.29

Each separate church exists and is governed by its private constitution and its proper rites according to difference of locality and the good judgment of each. That is the true position of National Churches.30

Tucker points out that the laws of Ina and Alfred “encouraged the development of the centralized English state and enhanced the authority and prestige of the Catholic church”.31 Gradually, the Church was gaining in influence: it appropriated the right to adopt and enact laws independently of the temporal power; it drew up decrees which granted the Church immunity from taxation; monasteries received extensive land endowments for perpetuity. The growing influence of the Roman Catholic church triggered friction between the local old elite and the advocates of the new religion. The first uprising against the new faith and a near return to worshiping idols and paganism was fomented by king Eadbald (Æthelbert’s son), whose marriage was condemned by the Church – he married his father’s wife. As a result, many Christian missionaries became vulnerable and were forced to flee from England, it was the first case of the persecution of the clergy. The conflict lasted for about a year; eventually, Eadbald gave up, converted to Christianity and renounced his marriage. Ultimately, the Pope was proclaimed ‚true Emperor, lord over all kings and princes, and commander of the earth‛.32 The Pope established the hegemony of the Latin language over all European languages and the hegemony of the Catholic Gospel.

Martyrdom in Anglo-Saxon societies was mainly connected with a cult of murdered kings. Members of royal families were canonized due to their violent deaths and some miracles accompanying their deaths, for example a ray of light rising from the place of murder. The first case of martyrdom for the faith was the murder in the seventh century of two Mercian princes – Wulflad and Rufinus, – who were killed by their father king Wulfhere because they were Christianized. David Rollason considers that “the veneration of martyrs by murder had a long future in England and that such veneration was to retain a decidedly political complexion”.33 Miracles accompanying death were considered a sign of “God’s mighty power and judgment”.34 Quentin Skinner summarizes the implications of this period for the future:

During the centuries when Christian perspective was imposed on Western Europe, the outcome in human terms was nothing short of catastrophic. …The attempt to challenge the powers of the Catholic Church in the 16th century led to several generations of savage religious war.35

Precursors of the Tudor Reformation

Overview

The Protestant movement was, undoubtedly, the greatest event in the religious life of England and Europe. In the 1520s, the pretensions of the Church to supremacy in state affairs were assailed because they began to run counter to the developing national spirit which gravitated to the monarchical idea. It was not yet the Reformation as we understand it, but an entree to it. The two opposing ideologies were locked in mortal combat dooming zealots on both sides to suffering. The break with the Catholic Church of Rome initiated by Henry VIII, who was guided not only by personal ambitions, but by political and religious expedience, was a significant landmark of the age. But the Reformation did not appear out of nothing; it was prepared by major and minor events of the previous epochs among which the most significant was the return to God’s word (Gospel) and the ensuing multiple translations of the Bible and Psalms in abortive attempts to escape the dominance of Rome.

In modern theories of the history of Protestantism, the generally accepted view is that it originated in Germany in 1517 and is associated with the name of Martin Luther and his Ninety-five Theses as a reaction against abuses and errors made by the Catholic Church. However, it seems to be a rather simplistic approach to a complicated problem of the Great Ecclesiastical Division of the 16th century. In search of the roots of Protestantism and historical precedents of disobedience to the Pope in England we should go back to the reign of King John (13th century) and to the personality of John Wycliffe (14th century).

King John: An Attempt at Disobedience and its Implications for the Tudors

The main issue of the time was the irreconcilable problem of relationship between the temporal and spiritual powers. Pope Innocent III (from 1160 to 1216) was one of the most powerful of the medieval popes who held both the miter and scepter which gave him supremacy over all European kings. The audacious project of the Pope was to devoid European sovereigns of their right to appoint high ecclesiastical dignitaries thus making all of them entirely dependent upon the Vatican. It was both humiliating and posing risks to the royal rights and nation’s independence. The first attempt to lash out against the Pope’s dominance took place in France. In 1141 when a conflict flared up between Louis VII (ruled from 1130 to his death in 1143) and Pope Innocent II over the appointment of the Archbishop of Bourges, Pierre de la Chatre. Outraged, Louis swore that so long as he lived the papal candidate should never enter Bourges and actually bolted the gates of the city. An interdict was imposed upon the king’s lands, and a two-year war broke out between the king and Theobald, Count of Champagne, for having sided with the Pope in the dispute over Bourges. The royal army occupied Champagne and burnt the town of Vitry where a thousand people perished in the fire. The conflict was settled as Pierre de la Chatre was installed as archbishop of Bourges and Louis agreed to lead a Crusade to the Middle East to atone for his sins.

In England, King John (ruled from 1199 to 1216), who was considered one of the weakest kings in the history of England, nevertheless, defied the omnipotent pontiff. The Pope excommunicated and accursed King John. In response, the king in his anger banished the clergy and monks of Canterbury out of the land “to the number of threescore and four [sixty-four], for their contumacy and contempt of his regal power”.36 Innocent pronounced the general interdiction throughout England that the church doors were shut up: people could not get wedded, baptize their babies, or perform a funeral service. The purpose was to instigate a rebellion against the king.

The King stood up to Vatican for two years, but gave in when the French forces moved towards London at the instigation of the Pope. John submitted himself unreservedly to the Pope’s supremacy in return for protection. This is how the Scottish historian of religion James Wylie describes this humiliating occasion (Figure 1).

Taking off his crown, John laid it on the ground; and the legate, to show the mightiness of his master, kicked it about with his foot like a worthless bauble; and then, picking it out of the dust, placed it on the craven head of the monarch. This event took place on the 15th May, 1213. There is no moment of profounder humiliation than this in the annals of England.37

King John’s abortive attempt to stand up to the papal dominance is described in John Bale’s38 drama Kinge Johan (1538), the anonymous history play, The Troublesome Raigne of John, King of England (1591), and Shakespeare’s The Life and Death of King John (1623). Bale’s play, in my opinion, is most illustrative of those historical events for several reasons: 1) it is the first history drama; 2) it is written as Protestant propaganda and has a strongly pronounced anti-Catholic bias; 3) it dramatizes the reign of a historical English king, 4) Bale portrays the monarch as a character of virtue and is, probably, the first to revisit the unflattering medieval view of the king.

In the play, King John refuses to acknowledge the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephan Langton, appointed by Pope Innocent and tells so to Pandulphus, the legate from the see of Rome, in a laconic way:

but as for Stevyn Langton playne

He shall not cum here, for I know his dysposycyon.

There shall no man rule in the lond where I am. kyng

With owt my consent, for no mannys [man’s] plesure lyvyng.39

John explains his capitulation in the face of French invasion with “ships full of gun-powder” bound for England by his desire to prevent bloodshed: “I do not thys of cowardnesse,/ But of compassyon in thys extreme heavynesse./ Shall my people shedde their bloude in suche habundaunce?”40

Two years later on the 15th of June, 1215, under the pressure of barons John signed the Magna Charta,41 which was in effect to tell Innocent that the king “took back the kingdom which he had laid at his feet”.42 But despite this, king John’s reputation was ruined and since then he has been regarded as a coward, an impious man, and the worst king to rule England. Holinshed rebukes the writers of John’s time who “of meere malice conceale all his vertues, and hide none of his vices; and interpret all his dooings and sayings to the woorst.” He goes on to say that the order of John’s life written by Catholic chroniclers “may seeme rather an invective than a true historie”.43 Holinshed gives a more objective description of John’s reign: “Certeinelie it should seeme the man had a princelie heart in him, and wanted nothing hut faithfull subiects to haue assisted him in revenging such wrongs as were doone and offered by the French king and others.44 He might have achieved more if “the loialtie of his subiects had remained towards him inviolable,” if the courtiers & commoners had performed their duty to their sovereign and the state. But “both courtiers and commoners fell from king John, their naturall prince, and tooke part with the enimie; not onelie to the disgrace of their souereigne, but euen to his ouerthrow”.45

King John’s Reputation Revisited

Under the Tudors, King John’s reputation was seriously reconsidered. “The medieval villain became a hero of English liberty, a kind of anticipant Protestant, a lonely pioneer in resisting the tyrannies of Rome”.46 One of the first who undertook to revise the medieval view of King John was William Tyndale47, who in 1528 wrote:

Consider the story of King John, where I have no doubt they [papists] put the best and fairest description for themselves, and the worst for King John – for I suppose they wrote the chronicles themselves. Would the legate not have cursed the king with his solemn pomp, because the king would have done what God commands every king to do, and for which God has put the sword in every king’s hand?48

Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister and orchestrator of English Protestantism, used King John in his propaganda of a new, true and pure church freed from the vices of Rome: king John was a convenient figure to draw historical parallels and present him as a “much-injured, blameless, and stoic” man who withstood the subversive attempts of the Catholic church to undermine the authority of the anointed English king. “The historical John prefigured Henry VIII, since both resisted the Papacy”.49

For the purpose of promoting a figure of dubious merits and poor reputation as king John was, a very potent and shrewd instrument was needed to rehabilitate the disgraced king. And this instrument was found – the drama – a play that would demonstrate the pope’s wickedness, wiles of the Church and vulnerability of the king turning him into someone close to a Christian martyr. This specific genre was chosen to assimilate and formulate ideas necessary to exert ideological influence. Also, a suitable playwright was found in the person of the priestplaywright John Bale, who had written by that time several anti-papal interludes and who wrote the first Protestant play King Jonah in 1538, which for contemporary audience became potent anti-Catholic propaganda. Some aspects of the play are worth considering in some detail.

The plot of the play unites historical factuality and allegory. Widow England complains to King John that she is torn from her husband, God, by the clergy, who profess a false religion. The king promises to help her, repudiates the appointment of the archbishop of Canterbury, which exasperates the Pope who buys over nobility and commoners, bishops and lawyers, and the clergy. Betrayed by all his subjects, King John resigns his scepter and crown to the Pope, who levies a heavy tribute that drains the king’s treasury. Moreover, the Pope sends a monk with a bottle of poison to the contumacious king. The monk and the king drink of the same bottle and die. Eventually, Verity (Truth) and Imperial Majesty, a personification of royal authority, namely Henry VIII, appear, drive popery out of England and promise to lead England to “the land of milk and honey”.

In Bale’s presentation, John is victimized by the Pope; such vulnerability appealed to the English subjects. Most important, the closing scene is, by all appearances, a manifesto for a new social order based on Protestantism and the Act of Supremacy,50 in which the struggle between the state and the Church for absolute power is resolved in favor of the royal authority. The act declared that the king was “the only supreme head on Earth of the Church of England” answerable only to God. This is proclaimed from the stage verbatim by Verity:

Verity:

In hys owne realme a kynge is judge over all,

By Gods appoyntment, and none maye hym judge agayne,

But the Lorde hymself: in thys the scripture is playne …

King is the supreme head of the church,

Bishopp, monke, chanon, priest, cardynall, pope:

All they by Gods lawe to kynges owe their allegeaunce.

Than shall never Pope rule more in thys monarchie.”51

A pejorative description is given to the corrupt and decaying Church, which has been distorting God’s word and to its leader who is believed to have usurped temporal power. “The prelates do not preach, but persecute those that the holy scriptures teach”.52 The Church has been torturing Gospel readers by putting them in irons. The Pope is called “thys bloudy bocher,” who oppresses Christian princes by fraud and craft “tyll he compell them to kysse hys pestylent fete,/ Lyke a levyathan syttynge in Moyses sete”.53 The Pope is compared to the devil who sprang out of the bottomless pit blowing forth a swarm of grasshoppers and flies, venomous worms, adders, whelps and snakes. The discourse of anti-clericalism is being shaped, which is informed with hatred and intolerance.

Equally important are the lines in the epilog which are devoted to a discussion between Imperial Majesty and Civil Order about what should be done to the enemies of the crown and religion. The answer is “they are wurthie to dye” and be no more. The offender should be taken to Tyburne,54 hanged and quartered, “and on London brydge loke ye bestowe hys head”.55 Such punishment must have become common practice at that time as in the Protestant ballad A Letter to Rome to Declare to the Pope John Felton56 his Friend is Hanged in a Rope (1570) we find a description of an execution word for word repeating what is proclaimed in the play. The ballad is written in the form of a letter to the Pope informing him of the death of his “obedient childe and knight,” who exalted the Catholic doctrine, defended the Pope’s supreme power and shed his blood for this cause.

Ring all the belles in Rome,

To doe his sinful soul some good:

His quarters stand not all together,

For why? they hang

Unshrined each one upon a stang57:

Thus stands the case,

On London gates they have a place.

His head upon a pole

Stands wavering in the whirling wind.58

Wycliffe the “Morning Star of the Reformation”

A serious cause for extreme violence was the issue of the Scriptures that instigated the struggle of the Catholic church for language domination. From the fourth century, the Bible began to be hidden from people. Believers must be separated from God’s word and believe “nothyng but as holy chyrch doth tell”.59 In Bale’s play, Sedition explains to King John how vulnerable faithful preachers are:

King John: Why, giveth he no credence to Christes holy gospell?

Sedition: No, ser, he [Pope] callyth them heretics

That preach the gospell, and seditious schismatic

He tache them, vex them, from prison to prison he turns them,

He indicts, them, juge them, and in conclusion he burns them.60

It is common knowledge that the problem of biblical translations has a long and tragic history. As early as the 14th century, Wycliffe (1320–1384), no doubt, the greatest intellectual of his time whose teaching “made him the greatest of all the Reformers who appeared before the era of Luther”,61 spoke strongly against the temporal [royal] power of the Pope, who could only be a spiritual ruler; moreover, he argued that the monarch should have authority over the church in his country. Most important, Wycliffe always preached up the authority of Scripture over the authority of the Church. While studying the Bible, he saw that the ideas of the Gospel ran counter to what was preached and practiced by the Papacy. He became a harsh critic of many of the teachings of the Pope, whom he called “Antichrist,” and accused him of the “heresie of simony”.62

Inasmuch as the Church had appropriated the right to interpret the Scriptures and preach God’s Word as they saw fit, Wycliffe spearheaded the struggle against the hegemony of the Latin language and advocated translations of the Bible into the common vernacular. It is believed that he completed a translation of the Bible from the Vulgate63 into Middle English (called Wycliffe’s Bible). He was convinced that people should have firsthand knowledge of the Bible without mediation by the Pope. His translation deprived clerics of the unique right to interpret holy writ for laypersons64 and let ordinary men and women read and interpret the Scripture for themselves. Wylie characterized Wycliffe as follows, “His appearance marked the close of an age of darkness, and the commencement of one of Reformation”.65 He laid down the main principles of Reformation and brought nearer the advent of modern times.

Wycliffe considered that the Church and its acolytes had forgotten the vow of poverty and had become enormously rich by accumulating land and gold. They formulated a dogma that the Church’s “accumulations should go on while the world stood; he who shall withdraw any part thereof – so much as a single acre from her domains or a single penny from her coffers – robs God.” These large possessions were exempt from taxes and public burdens. In these overgrown riches Wycliffe discerned the source of innumerable evils.66 Wycliffe’s accusations of the Pope might have brought him to the stake in his lifetime and certainly made him the best hated man in Rome because forty years after Wycliffe’s death, in 1427, Pope Martin V (head of the Catholic Church from 1417 to his death in 1431) ordered that Wycliffe’s bones be exhumed from their grave, burned and cast into the river Swift. Rome applied to Wycliffe what Foucault classified as “death-torture” – the art of “tortures that take place even after death: corpses burnt, ashes thrown to the winds or drowned in a river, or bodies exhibited at the roadside”.67 The Lollards Bible translation was associated with religious dissidence, was punishable by death, and many people perished in the flames due to it.

The Lollards

Wycliffe’s ideas did not die with him, but were espoused by different layers of society. The most devoted followers were the Lollards, a peculiarly English religious movement, including “a wide range of people from university-educated scholars to members of the gentry to village artisans”.68 Lollard literature of the time is mainly anticlerical and anti-monastic. The famous poem Heu! quanta desolatio Angliae praestatur (Alas! how great is the desolation of England) criticizes clerics, who instead of being “lights and mirrors to the laity”, are immersed in the darkness of rapacity. Prelates are promoted by means of gift, quill, and entreaty. Their sins include building fine houses, begging, currying favor with the rich and mistreating the poor. This poem closes with a claim by the poet that he used to be a monk, but is one no longer).69

It is amazing how this characterization of clerics resonates with the lines of an ode written in 540 by Ambrosius Telesinus70 (cited from Holinshed’s chronicles):

Wo be to that priest yborne,

That will not cleanly weed his corne.

And preach his charge among:

Wo be to him that dooth not keepe,

From ravening Romish wolues his sheepe,

With staffe and weapon strong.71

As the Church had failed to punish Wycliffe in his lifetime, the papists persecuted anybody who held Wycliffe’s opinions, be it an old woman or a young lad, clergymen or laity. Henry IV’s (king of England from 1399 to 1413) enthronement aggravated the situation of the Lollards. The crown and the Church united in an attempt to completely dispose of the heretics, who traveled all over the kingdom preaching the Gospel attracting new followers. Under Henry IV, a law was passed condemning people to death for religion. It enacted that all “incorrigible heretics” should be burned alive. “Henry IV was the first of all English kings that began the unmerciful burning of Christ’s saints for standing against the pope”.72 A special statute was passed by the king and his nobility called Ex Officio infamously known as a “bloody statute,” which vested in sheriffs, mayors, and bailiffs the rights to pass sentences and put to death offenders of the church and Pope.

…take the said persons so offending, and cause them openly to be burned in the sight of all the people; to the intent that this kind of punishment may be a terror unto others, that the like wicked doctrines and heretical opinions be no more maintained within this realm and dominions.73

One of the most vehement opponents of the Lollards was Thomas Arundel, archbishop of Canterbury, who composed Constitutions against “heretical preachers,” forbade the works of Wycliffe and banned any translation of the holy Scripture into English by way of a book, libel, or treatise;74 those people who read any such books “should be punished as sowers of schism, and favourers of heresy.” It was Arundel who pronounced condemnation to a John Badby, a tailor, the first layman to be burnt in the reign of Henry IV. The “hearing became a show trial of national importance”.75 His execution was horrifying: he was put in the barrel tied to the stake and burnt to ashes in the presence of Prince of Wales, future king Henry V, who tried to persuade John to recant but failed. The translation of the Bible into the vernacular was categorized as a challenge to Catholic authority.

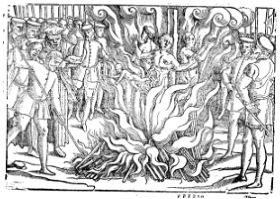

Violence at that time took epic proportions. In 1401, the first act for burning people for their beliefs was passed by parliament and was soon put into practice. Lollards were hunted down, and mass executions became a new normality (Figure 2). The methods were Jesuitical: daughters were made to set fire to their fathers; people were compelled to carry fagots to make fire for their friends and relatives as a penance; many people had their right cheeks burnt; those who were imprisoned were tortured by cold, hunger, and chains. Although persecuted, the Lollards continued as an underground movement right up to the Reformation.

William Tyndale a Martyred Translator

Another famous translator of the Bible whose fate was much more tragic was William Tyndale (1494–1536), ironically, the translator of the first Reformation New Testament based directly on Hebrew and Greek texts. He had to flee England and work on the continent where the first complete edition of his New Testament was published in 1526. His Bible was proclaimed heretic by the Vatican. Catholic and secular officials, including Thomas More accused him of purposely mistranslating the ancient texts in order to promote heretical views. Tyndale’s anti-clericalism is explicitly pronounced in his treatise The Obedience of a Christian Man (1528):

Our clergy have robbed all realms, not only of God’s word, but also of all wealth and prosperity. They have withdrawn themselves from all obedience to princes, and separated themselves from the laymen, counting them viler than dogs; and they have set up that great idol, the whore of Babylon, the antichrist of Rome whom they call pope.76

In his works, Tyndale claimed that Rome emanated evil and violence:

The emperor and kings now-a-days are nothing but hangmen to the pope and bishops, to kill whomever they condemn, without any fuss. … Who slew the martyrs, and all the righteous that ever were slain? The kings and the temporal sword slew them at the request of false prophets. What signifieth that the prelates are so bloody? When no man dare for them once open his mouth to ask a question of God’s word, because they are ready to burn him.77

Another humanist, John Foxe, fully agrees with Tyndale when he discusses the torments and the death penalty stating that it was borrowed “from the papal laws and brought into the Christian arena” and that burning up “with fiery flame the living bodies of wretched men who err through blindness of judgment belongs more to the spirit of Rome than to the spirit of the Gospel”.78

His depreciatory attacks against the popes, cardinals and bishops cost Tyndale his life. Rome sent spies all over Europe to hunt him. One Henry Phillips recognized Tyndale, made friends with him and gave him away. Tyndale was arrested; a speedy trial sentenced him to being strangled and burnt (Figure 3). Cromwell tried to intercede, but Henry VIII was adamant: he wanted Tyndale’s death on personal grounds. Tyndale opposed the annulment of Henry’s marriage with Katherine of Aragon.

Tyndale’s last words were: “Lord! Open the king of England’s eyes.” Ironically, two years after Tyndale’s death in 1538, Henry VIII ordered that copies of the Bible in the vernacular should be placed in every church; the English language was no longer considered heretical, and the king got all credit for promoting God’s word and disseminating the knowledge of the Scriptures. The Bible, which got the Royal License, was in fact that of Tyndale, the strangled and burnt translator.

Catholics vs. Protestants in the Tudor Dynasty

Henry VIII: from the “Defender of the Faith” to the “Architect of the English Reformation”

The Tudor era was one of intense religious, political and intellectual restructuring triggered by the spread of humanistic thought and religious changes which started in Germany. Henry VIII’s religious policy is well-known for its inconsistency and alterability: ideological and political incoherencies lay behind Henry’s laws. In 1529, he issued a Proclamation for “resisting Heresies, sown by the Disciples of Luther, a perverter of Christ’s Religion,” which ordained that every heretic, who “corrupted by heretical and blasphemous books should be put in execution”.79 Henry’s religious ambivalence and dithering resulted in much violence: both conservatives and radicals got into serious trouble. On one day three preachers were burnt for heresy “against popery” and three conservatives were hanged as traitors for speaking in favor of the pope, and all at one time.80

The king’s ordinance triggered a process that today might be called a humanitarian disaster with a long list of martyrs persecuted, tortured, and burnt. The first English Protestant martyrs of the Reformation were Thomas Hitton and Thomas Bilney. The crime of the former was that he smuggled two copies of the Tyndale Bible into England and the crime of the latter was that after having read the New Testament in Greek he started preaching the Gospel. Both were charged with heresy and burnt alive. The most ardent persecutors were Henry VIII, who received from Rome the title “The Defender of the Faith”, Cardinal Wolsey, Thomas More, several bishops and friars. Cardinal Wolsey conducted the interrogation of Bilney himself, and Thomas More signed the writ of discharge to burn Bilney saying, “Go your ways and burn him first; and then afterwards come to me for a bill of my hand”.81 On his way to the stake, Bilney gave alms to the poor. His last words were “Jesus! Credo!” Three times the gusts of strong wind blew the flames away from him until one of the officers pushed him to the bottom of the fire which consumed the martyr.82

Under Henry VIII, political interests of different groups of courtiers vying for power or influence on the Monarch were camouflaged as guardianship of religious purity and vice versa, “dispreferred” religious beliefs were treated as treason. Thus Henry Howard, a poet who introduced the sonnet to English poetry and was the first to write in blank verse, was executed for treason on trumped up charges of being a devoted Catholic though he fought against the Catholic rebels in the revolt of 1536 and his poems are evidence to the contrary. In the poem A Satire against the Citizens of London, the poet compares the licentious manners of the citizens with the manners of Papal Rome unbecoming of a Christian community. He blames Rome for innocent victims and warns that justice will triumph:

O! shameless whore!…

O! member of false Babylon!

Thy dreadful doom draws fast upon;

Thy martyrs’ blood, by sword and fire,

In heaven and earth for justice call.

The Lord shall hear their just desire;

The flame of wrath shall on thee fall!83

He prophesies the fall of Catholic temples and people’s rapture at it. Howard’s tragedy was that he was tried and executed on allegations of three witnesses that the Howards intended to usurp the throne. He was betrayed by his wife and his mistress, who testified against him. He demanded a public trial, but was denied. One week before Henry VIII’s death, Henry Howard was beheaded in the Tower.

Religious and political motives were mixed in the case of Ann Askew, a lady from a noble family and a female preacher of the Gospel. The prevailing motive for her indictment was to get Anne to implicate Queen Kateryn Parr, the last wife of Henry VIII, which she refused to do. She was put to the rack until all joints were torn apart. It was a flagrant legal violation as the law forbade to apply this torture to women. She had to be carried to the place of her burning in a chair because she could not stand and then tied to the stake. She is the only woman on record to have been tortured in the Tower of London. King Henry VIII granted pardon to her torturers.

Henry’s marital problems coupled with his rampant desire for absolute power made him revise his policy and undertake decisive steps to get rid of Rome’s domination, side with English reformists on some ecclesiastical issues, and promulgate English as the language of liturgy and holy writ. In 1535, Henry sent a royal circular letter to bishops that “Rome’s authority was but usurpation” and that sermons denouncing the pope should be preached in every diocese.84 What attracted Henry in the Protestant movement was their rhetoric in support of the royal supremacy and control over the ecclesiastical body as well as channeling the Church’s revenues to the Crown. However, until his death Protestants were tortured and executed with the king’s tacit approval.

John Colet

Henry’s wavering and his vague ideological commitments were interpreted by many researchers as a search of a middle way.85 Among the Catholic clergy there were some who aspired to introduce serious changes, but leave the doctrine intact. The most influential figure was John Colet (1467–1519), a leader of Christian humanism, Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, whom Henry actually saved from death. Colet did not wish to destroy the Church but wanted to improve it from within and turn it into a perfected and purified institution. His most famous speech was the Convocation Sermon made at St. Paul’s in 1510 addressed to the “holy Fathers,” in which he exposed the evils of the modern church. Colet was asked to give a sermon against the Lollards, but instead, he castigated the sinful clergy. The purport of his sermon was the urgent necessity of reforms. In his view, reformation must begin with high Church dignitaries and be followed by lower echelon.

For it was never more need, and the state of the Church did never desire more your endeavors. For the spouse of Christ, the Church, whom ye would should be without spot or wrinkle, is made foul and evil-favored, as saith Isaiah, ‚The faithful city is made a harlot‛.86

Colet sees four evils in the life of the Church: “devilish pride, carnal concupiscence, worldly covetousness, and secular business”.87 As a result,

The dignity of priesthood is dishonored; priesthood is despised because priests are unlearned and evil; the hearts of prelates are so filled with gluttony and drunkenness and cares of the world that they cannot lift up their minds to high and heavenly things (ibid., p 3).88

He grieves that “the face of the Church is made evil-favored [ugly] because promotions are made by favoritism or familial ties, not by the right balance of virtue.” He argues that these evils stem from the secularization of the Church: “Since this secularity was brought in, and the secular manner of living crept in in the men of the Church, the root of all spiritual life was extinct”.89 The urgent necessity of the day was “reformation and restoring of the Church’s estate [condition]”.90

Colet’s translation of the Lord’s Prayer got him into serious trouble with prelates. He was in imminent danger of being burned at the stake as a heretic. Only Henry VIII’s intervention saved him from “stake and fagot.” He died in his bed, but even after his death some prelates insisted on Colet’s body being taken from its coffin and burned.91

John Skelton

Probably, one of the bishops who attended the convention was John Skelton,92 who was so impressed by the sermon that wrote a poem Collyn Clout, his first literary attempt at criticizing the clergy, putting his anger in the mouth of a simple shepherd by the name of Collyn Clout. The sermon and the poem share similar attitudes to the contemporary ecclesiastical situation in England93 and use the same reasoning. Like Colet, Skelton’s Collyn is the defender of the Church though he feels a need to reform it; he satirizes the friars, the bishops and the Church in general. He accuses them of haughtiness and vanity, of neglecting their duty, of laziness and ignorance, and most important, of failing to preach God’s truth. He attacks the cowardice of the prelates; calls them “herted like an hen” and says that “Boldnesse is to seke/ The Churche for to defend”.94

In the final lines we hear the voice of a prelate, who is indignant that a “daucocke or losell”95 dare preach the Gospel “agaynst vs of the (Privy) counsell?”96 He threatens such preachers with imprisonment and other great torments. This voice represents a group of the clergy who perpetrated violence.

Ye prechers shall be yawde [cut down];

And some shall be sawde [cut asunder],

As noble Isay,97

The holy prophet, was;

And some of you shall dye

Some hanged, some slayne,

Some beaten to the brayne [brain]

And we wyll rule and rayne,

And our matters mayntayne.98

In these lines the motif of violence is most vividly manifested. Collyn Clout became vox populi combining “dissident voices of the discontented laity, Wycliffite heretics, and other followers of Luther”.99

Robert Crowley

Similar criticism of the clergy was put into verse by Robert Crowley (1518-1588), a printer, poet, polemist, a Puritan of the narrowest school, a preacher and social reformer. He is one of the most important literary figures of the English Reformation. He flourished during the reign of Edward VI, but had to flee England under Mary I. When the Reformation was renewed under Edward VI, the poet set his hopes on the young king. In An Informacion and Peticion agaynst the oppressours of the pore Commons of this Realme, he addresses Edward VI:

And this reformation had, no doubt the majestie of God shall so appeare in all your decrees, that none so wicked a creatur shalbe founde so bolde as once to open his mouth against the ordre that you shal take in all matters of religion. … All the Kynges christined shal learne at you to reforme theyr churches. You shalbe euen the Light of all the world.100

While Edward was alive, Crowley expressed hope that Catholicism had no future in England.

Under Queen Elizabeth, he held many important positions in the Church preaching anywhere and on different occasions. Crowley was at the center of a group of writers, called “gospellers,” who wanted to retell the Bible in popular literary forms. The Five Tracts written by Crowley are the most valuable examples of Puritan writings. In The Voyce of The Last Trumpet printed in 1550 (its unique copy resides in the British museum), Crowley severely criticizes lewd and unlearned priests for their ignorance and false doctrine. Sunk into the sin of gluttony, drunkenness, and covetousness, they neglected their duty to their faithful community. He incriminates to them that they have not fed the hungry, nor comforted the sorrowful, nor healed the sick; they have not brought back “the stray sheep” but displayed extreme cruelty to all of them.101

In another tract Pleasure and Payne, Crowley accuses the clergy of bringing many innocent people to destruction:

Ye made your waye, Lyke gredy woulves,

You layde to theyr charge herecie,

But you dyd them falsely belye,

For many of them you haue slayne

Wyth most extreme and bitter payne.102

The poet welcomed the banishment of Catholic clerics from the realm:

Awaye, awaye ye wycked sorte!

Awaye, I saye, oute of my syght:

Henseforth you sha[ll] haue no conforte.

But bytter mournynge daye and nyght,

Extreme darknes wythouten lyghte.103

Crowley was a dedicated Protestant and had rigorous views on unflagging dedication to one religion. Though he spent the years of Marian reign in a comfortable exile, he considered recantation of the victims of the regime as an ignominious betrayal of faith. For him, martyrdom was “a preferable act of resistance” on the part of people under persecution. Recantation destroys ideologically significant Protestant stoicism, and plays into the hands of their adversaries.

Psalms as an Inspiration for Violence

Religious writings informed with violence were used as a justification of Christian atrocities in the name of God. The best illustration may be imprecatory psalms whose cultural significance in early modern England ought not to be underestimated. In the 16th century, there were numerous translations, adaptations, and paraphrases of psalms in English by the leading poets such as Thomas Wyatt, Robert Crowley or William Kethe. Psalms became an essential component in the rapid spread of Reformation ideas.104 This religious genre expresses a whole range of human emotions from joy to sorrow to the desire of avengement. Out of the few imprecatory psalms that speak of violence against the enemies of God, Psalm 137 called “the quintessential psalm of the Renaissance and the Reformation”,105 is the most inexpiable. The psalm is devoted to the Babylonian exile of the Jews, their sufferings in the outland, and desire to avenge themselves on Babylonians. The last stanza contains the lines written in vengeance against enemies may seem shocking to the modern reader.

O Daughter of Babylon, doomed to destruction

happy is the one who repays you

according to what you have done to us.

Happy is the one who seizes your infants

and dashes them against the rocks (NIV 1984, Ps. 137:8-9, p. 444)

The same text in different historical circumstances may shape different theological interpretations, as well as at different levels of profundity. If we take a metaphorical level of analysis, we can see that scholarly exegetes such as Bede interpreted the verses of this psalm as allegorized narrative of Jewish captivity in Babylon or as remembrance of this captivity when the Hebrew people were cast from the joys of Paradise to the valley of weeping.106 “The daughter of Babylon” stands for Rome, whereas “infants” are the first motions of evil thoughts that should be dashed against that Rock which is Christ,107 nevertheless, the metaphors are bursting with so much hatred, asperity and violence that the metaphor is perceived in a very direct sense. The lines echo Isaiah’s prophesy concerning the fate of Babylon in the Old Testament:

Whoever is found will be thrust through,

and whoever is caught will fall by the sword.

Their infants will be dashed in pieces

before their eyes;

their houses will be plundered

and their wives ravished.108

Among imprecatory psalms, Psalm 118 was a favorite of Mary’s. She chose a line from this psalm for a legend on the noble coin issued in her time. It is the Te Deum expressing gratitude to God for helping the righteous to root out all heretics. Each line of the psalm is resonant with Mary’s feelings and actions:

The Lord is with me; he is my helper. I look in triumph on my enemies….

They surrounded me on every side, but in the name of the LORD I cut them down.

They swarmed around me like bees, but they were consumed as quickly as burning thorns;

in the name of the LORD I cut them down.109

The Psalm is a justification of Mary’s persecution of heretics, whom she burnt mercilessly. Considering the historical situation of Mary’s war for the reinstatement of her faith, we can see why the psalms reinforce the use of violence and sacralize it as a weapon against the impious. Each line of these Psalms inspires and justifies killing.

Mary and Elizabeth as Proponents of Sacred Violence

Tudor female monarchs imposed two opposed religious doctrines on their subjects, threatening them with imprisonment and execution. With the enthronement of Mary I (reigned from 1553 until her death in 1558) England saw a comeback of the Catholic faith and a new surge of violence in the realm: 300 people were executed for religious reasons. In 1554, Parliament revived the medieval laws against heresy, bringing violence within the national legislative framework. Mary I was “obsessed with the idea of her supreme duty to do battle with Antichrist. For conscience’ sake she offered up a whole holocaust of martyrs”.110 Recent studies offer a more positive assessment of Mary I’s regime, though. To do her justice, she reconstructed universities turning them into “powerhouses” of Catholicism, refurbished some abbeys and churches, restored libraries, repaired stained-glass and woodwork in ruinated cathedrals. Eamon Duffy considers that the burnings were inevitable, and their efficacy in achieving the goals of political stability was high; it reduced the number of protestant activists: some were burnt, others exiled, still others demoralized.111

It is generally accepted that violence abated under Elizabeth I (reigned from 1558 to 1603): 200 martyrs lost their lives. These people were executed formally for treason because to deny the Act of Supremacy was considered high treason. “By a statute of 1571 it was made treason to call the Queen heretic, schismatic, or usurper, to introduce Papal bulls, and to send money to fugitives across the seas”.112 In addition, there were numerous executions as a result of the suppression of uprisings. The number of executed insurgents many of whom were Catholics is estimated at 6 to 7 hundred.113 Historians claim that under the Tudor monarchy, torture became a “royal prerogative” in cases when the safety of the state was held to be in danger. “The climax of this development was reached during the reign of Elizabeth”.114 In her time, England “judicially murdered more Roman Catholics than any other country in Europe”.115

The country continued to be confessionally divided. Approximately up to 1566, the papal policy in relation to England and personally Elizabeth was rather lenient. But with the accession of Pius V, a fanatic of a most rigid sort, a policy of seeking Elizabeth’s ruin and deposition was adopted by Rome.116 The Pope called on all English Catholics to assist in the overthrow of the queen, thus making them potential traitors, which the Puritan Parliament did not fail to avail of. Despite divergences in doctrinal principles, the sisters were united in one thing – violence was acceptable, necessary and should be universally applicable.

Apologia of Violence in the Sixteenth Century

The religious schism caused polarization in the intellectual atmosphere and affected the form and content of politico-religious messages sent to people in the works validating the policy of a respective prince. Both sides claimed they had been burning and tormenting for the cause of Christ, true faith, and social peace and accused the other side of instigating war. In the Elizabethan age, the eligibility of violence was discussed from two opposing points of view – Protestant and Catholic, each of the disputants accusing the opponent of abusing authority and using torture in excess. Protestant writers contended that treason and cruelty stemmed from the very principles of the Roman Church.117 Catholic writers argued that Protestant reformers provoked cruelties themselves.118 Ideological struggle took place at different levels. First of all, it involved popular polemic discourses of a politico-judicial character which tried to justify violence legalistically without involving religious arguments.

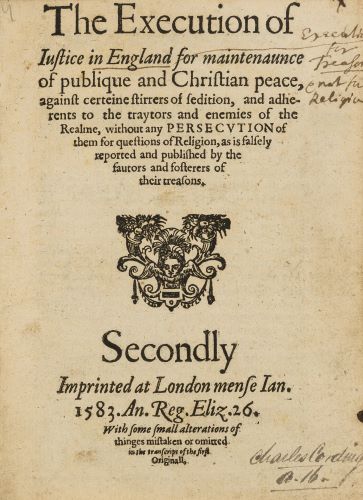

In 1583 and 1584, there appeared two tracts, the product of Protestant and Catholic apologetic. The sovereign power found legal justification for atrocities they practiced in the book by William Cecil119 The Execution of Justice in England written after two armed revolts against Elizabeth I (in the North in 1569 and in Ireland in 1579) instigated and supported by the Pope with the aim of deposing the queen and imposing a Catholic prince. Cecil offers two arguments in favor of torture: first, torture is a legitimate mode of political conduct; and second, felons were not persecuted for religion but for treason.

Gods goodness hath given to Her Majesty as to His handmaid and dear servant ruling under Him the spirit of wisdom and power, whereby she hath caused some of seditious seedmen and sowers of rebellion to be discovered and to be taken and charged with points of high treason, not being dealt withal upon questions of religion, but justly condemned as traitors.120

It was not difficult to engrain in public conscience the idea that Catholicism in any form was a threat to England’s well-being and Her Majesty’s legitimate right to govern the realm and the Church. Cecil’s work defines any Catholic activity, even private, as a public betrayal of the State and high treason; in this light, torture and execution should be understood as a fair punishment which the victim fully deserves.121 He insists that offenders were judged “by the ancient temporal laws of the realm, and namely by the laws of Parliament made in King Edward III’s time in 1330”.122 Whereas the “quick and wholesale execution of batches of Protestants by the preceding government of Mary”123 was illegitimate.

This short brochure received a quick retort from William Allen124 in his book A True, Sincere, and Modest Defense of English Catholics. He refutes Cecil’s assertion that English Catholics were put to death for treason alone and accuses courts of using an expanded definition of the concept. He argues that the Marian persecution was fully legal because heresy was declared illegal under the prevailing English law. Mary’s government was simply applying the obvious law when it sent hundreds of Protestants to the flames. In contrast, the Elizabethan government had no legal right to put Catholics to death since it had revoked a law against heresy early in the Queen’s reign:

We can prove Queen Mary’s doings to be commendable and most lawful, the other, toward us and our brethren, to be unjust and impious. … And therefore we most justly make our complaint to God and man that you do us plain violence and persecute us without all equity and order”.125

He blames in most indecent terms the protestant martyrs whom Catholics burnt. He describes Cranmer as “a notorious perjured and often relapsed apostate, recanting, swearing, and forswearing at every turn, and sacrilegiously married to a woman”,126 though Protestant bishops were allowed to have a wife. He accuses a pregnant woman at the stake of purposely giving birth to a child, whom he calls “filth and shame” and who was in cold blood thrown into the flames by executioners because “she looked for the glory of a saint and of a virgin martyr”127 (Figure 4). Foxe gives a different estimation of the terrible event:

Apparently [the baby] was ordered cast back into the flames by the provost and the bailiff. And so the infant baptized in his owne bloud, to fill up thenumber of Gods innocent Saintes, was both borne and dyed a Martyr, leaving behind it to the world, which it never saw, a spectacle wherein the whole world may see the Herodian crueltie of this graceles generation of Catholicke tormentors.128

Allen, however, insists that Catholic prelates were “persecuted for defense of our fathers’ faith and the Church’s truth”,129 so they ought to be considered real martyrs, whereas the persecution of Protestant prelates was “the due and worthy punishment of heretics, who shed their blood obstinately in testimony of falsehood against the truth of Christ” and cannot be treated as martyrs but as “damnable murderers of themselves”.130 Allen sums up: “The religion founded in the sacrament of Christ’s cross can be destroyed by no kind of cruelty. The Church is not diminished by persecutions, but increased.131

Protestant Martyrs in the Marian Reign

Among high dignitaries executed under Mary was Thomas Cranmer, the archbishop of Canterbury, a confidant of Henry VIII, tutor of Edward VI, and mastermind of the reformist movement. He ranked high with the king and was hated by Mary I because he divorced the king from her mother; married the king to Anne Boleyn, performed her coronation, was godfather to Elizabeth, did not acknowledge any other authority than that of the king. Revenge played a prominent role in the downfall of Cranmer. Mary used to say, “I would have Cranmer as a Catholic or else no Cranmer at all”.132

The most important thing for Cranmer’s enemies was to get a written recantation signed by his own hand, which they obtained by promising him his former greatness and the queen’s favor, though they knew that his death-warrant had already been signed. For love of life, the degraded archbishop signed all the six papers compiled by his torturers. The papists triumphed, and in order to consolidate their victory they staged another humiliating procedure – Cranmer was to deliver a sermon in St. Mary’s Church in Oxford before a great auditory in confirmation of his renunciation of the Protestant faith. He was to take the blame for the Queen’s mother’s divorce, to revoke all his books and writings as a false doctrine and proclaim the Papal gross doctrine as divinely revealed truth.133 But instead of repentant disavowal, the congregation heard:

I refuse the Pope as Christ’s enemy, and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine. My book teacheth so true a doctrine of the sacrament, that it shall stand at the last day before the judgment of God, where the papistical doctrine contrary thereto shall be ashamed to show her face.134

He was immediately taken to the place of execution. When the wood was kindled, stretching out his right hand, he held it in the fire until it burnt to ashes frequently exclaiming ‚This unworthy right hand!‛ meaning that it signed his shameful recantation.135 And then perished in the fire.

Victims of Religious Intolerance under Elizabeth

Bernardino de Mendoza (1540–1604), a Spanish diplomat, wrote to the King of Spain in 1581 about the fortitude of English Catholics in the face of most violent persecutions:

The priests they succeed in capturing are treated with a variety of terrible tortures; amongst others is one torment that people in Spain imagine to be that which will be worked by Antichrist as the most dreadfully cruel of them all. This is to drive iron spikes between the nails and the quick.

Notwithstanding the torture by which they sought to extract from the martyrs declarations of the persons with whom they were in communication, they were unable to obtain them, and I cannot exaggerate the beneficial effect that this has had, and the confidence that it has inspired in all sorts of people.136

One of the martyrs was a Catholic missionary priest, the famous “Flower of Oxford” Edmund Campion, a Jesuit, who had come to England “to sustain the faith of his Fathers” and had vowed not to be involved in any political activities. There are two possible views on this case: under the canopy of religion, Jesuits had the purpose of sedition and subversion of the Elizabethan regime whereas the opponents contend that the evil regime recast essentially religious activities as political in order to dispose of heretics. The former opinion is represented by John Stow137 in The Annales of England first published in 1592.

They forsook their native country, to live beyond the seas vnder the Popes obedience, (the pope practised the utter subversion of her [Queen’s] state and kingdome, to advance his most abominable religion). These men having vowed their alleagiance to the pope, gave their consent, to aid him in this most trayterous determination. And for this intent and purpose they were sent ouer to seduce the hearts of her majesty’s loving subiects, and to conspire and practise her graces death.138

Some modern researchers also consider that the Jesuit invasion of England which began in 1580 with the arrival of Edmund Campion had received commission from the Pope to sow disloyalty and sedition. About 250 Jesuits arrived, “some of them were actively engaged in treason, and all were legally traitors”.139

The opposite opinion is that Protestants “began to fear lest great alteration in religion might ensue, they thought good to alter the whole accusation from question of faith and conscience to matter of treason” whereas “these poor religious priests, scholars, and unarmed men could not be any doers in the wars of England or Ireland “.140 He asserts that they were ignorant of all conspiracies and “most innocent of that for which they were condemned; and that all was for religion and nothing in truth for treason”.141 The Jesuits were condemned on the grounds of “slanders and calumniations of certain heretics or politiques [opportunists] unjustly charging them with treason and other great trespasses against the commonwealth, to avert the eyes of the simple from the true causes of their suffering”.142 On the 1st of December 1581, Campion and other Jesuits were executed. That Campion was held in high esteem by people and not only Catholics becomes evident from the rumors that got about after his death that the river Thames ceased to ebb and flow on the day of his execution.

Another cause celebre was the Babington plot143 of 1586. The leader Anthony Babington came of good family; he was well off, had money and valuables of all sorts. It was love of religion and of country which inspired him, not mercantile interests.144 He attracted other conspirators. In his activities, he was aided by Spain, who in the long run failed him.

Babington therefore entreth into a new course, about invading of the Realme by forreiners, about the havens where they should arrive, about the aid that should joyne with them, about the delivery of the Queene of Scots, and about committing the tragicall execution of the Queene (Elizabeth) as he termed it. Babington labors to prove that it is lawfull to kill Princes excommunicate, and if ever equity and justice be to be violated, it is to be done for the Catholicke Religions fake.145

When the conspirators were arrested, they all confessed in full and all pleaded Guilty to the charge of intending to murder the Queen and conniving with Mary Queen of Scots. From the very beginning the plot was doomed as it was controlled or even orchestrated by Elizabeth’s intelligence service. Babington wrote to Elizabeth begging her for mercy; he even offered money for his release, but to no avail. All the conspirators were executed undergoing terrible torture.

This is how Holinshed’s Chronicle describes the event:

The first seven most malicious were executed neare the severitie of laws definitive sentence; and the consideration of their iudgments; namelie to ‘be drawn to the place of execution, there to be hanged till they were half dead, their bowels to be burnt before their faces &c. But the other seven were so favorablie used, as they hoong [hang] untill they were even altogither dead, before they suffered the rest of their judgement.146

The atrocity of the event went far beyond any reasonable cruelty. They were cut open; the bowels and hearts were ‘drawn’ out. Finally, the heads ‘which had imagined mischief’ were cut off, and the trunk was ‘quartered’. The dismembered fragments of the body were then available for public display. However, William Camden simply remarked in his annals “they were bowelled alive and seeing, and quartered, not without some note of cruelty”.147 The chronicler describes each conspirator as to his behavior and character. He stresses “the detested pride” of Babington, who would not kneel and pray for mercy in the face of death, but “stood on his feet with his hat on his head, as if he had been but a beholder of the execution.”148 He describes the caitiffs as “obstinate papists bewitched with an ignorant devotion”.149 He acknowledges the fairness of the sentence and even sees some lenience on the part of Elizabeth to the traitors, who mitigated the dire procedure after seeing the shock of the public. Holinshed admits that they were “more sharply executed than by law was censured”.150

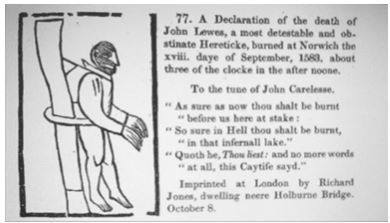

Elizabeth’s bigotry did not spare anybody. One John Lewes was neither a Catholic nor a heretic Protestant, he was what we would call today ‘agnostic’, nevertheless, he was burnt in 1583. Stow in his Annals describes the event in several short lines, “On the 17-day of Sept. John Lewes, who named himself Abdoit, an obstinate heretic denying the Godhead of Christ holding diverse other detestable heresies was burned at Pozwich Norwich”.151 This ordinary event was turned into something more significant. A broadside was printed with a rough sketch of Lewes tied to the stake (Figure 5); a ballad was written Shall silence shroud such sin aimed at exposing the depth of Lewes’ fall through denying the existence of God, but instead stirred the reader’s sympathy with Lewes for his unbending spirit and courage – he did not repent even in the face of death.

John Lewes was condemned for “brutishly/ God’s glorie defamed.” The Dean of Norwich, preachers, the Sheriff, tried to persuade him to “fall on his knees,/ his sinnes for to confesse.” “But he full stoutly stood therein … Not bending knee, hand, hart, or tong,/ to glorifie God’s name”.152 The most important stanza from the ballad is printed on the broadside. When the victim was threatened with everlasting torment in Hell, he simply answered, “thou liest‛ and died unshriven.

Conclusion

The concept of violence in the period under study became an issue of social relevance and a point of intersection of politics, religion, philosophy, ideology, and literature. The historical material provides ample evidence of religious association with violence. It also became a most common “political practice” to eliminate opponents of the Monarch and the state. Conceptually, violence at that time encompassed torture, agonizing death, as well as posthumous befoulment of the dismembered body. It was mainly connected with various degrees of physical pain or body maiming.

Though cases of religious atrocity were already registered in the AngloSaxon period, it attained its apex in the Tudor age. Under all the Tudors, legal violence was exercised without moderation or restraint: even imagining treason was made a capital offence punishable by death. Death in its turn was not simple hanging or beheading, but the continuation of refined torture aimed at prolonging suffering.

Violence in the name of God is a complex phenomenon, which was amply used during the religious schism started by Henry VIII. English society was divided along religious lines. Within one century, religion alternated three times entailing voluntary or coerced conversion that was accompanied by extreme violence used by militant zealots on both sides to do away with heresy and silence dissent.

Ideological efforts during this period were directed at the subordination of the subjects to a new political and religious reality. Ideology was transmitted via “mass media” of the time: sermons, drama, ballads and broadsides. It informed contemporary literature with new propaganda ideologemes and left to us a nuanced picture of the changing historical context.

‘Let penalties be regulated and proportioned to the offences, let the death sentence be passed only on those convicted of murder, and let the tortures that revolt humanity be abolished.’ Thus, in 1789, the chancellery summed up the general position of the petitions addressed to the authorities concerning tortures and executions. Protests against the public executions proliferated in the second half of the eighteenth century: among the philosophers and theoreticians of the law; among lawyers and parliamentarians.154

The Enlightenment condemned public torture and execution as an ‘atrocity,’ vestige of the past. However, in the 21st century, instead of abating or disappearing altogether violence has been given new momentum with mass punishments of nations and renewed gas chamber executions. This is a dangerous trend for the world.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by Athens Journal of History 10 (2024, 1-38), DOI:https://doi.org/10.30958/ajhis.X-Y-Z, under an Open Access license.