The modern tendency to separate the sacred from the pharmacological is a historical anomaly. In much of human history, the two were bound together.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Intoxicated Sacred

Across continents and centuries, human beings have sought altered states to bridge the gulf between the seen and the unseen. Hallucinatory substances, drawn from plants, fungi, and crafted brews, have often been more than mere intoxicants. They have served as sacraments, keys to divine realms, and catalysts for collective identity within religious traditions. While modern cultures often separate the sacred from the pharmacological, ancient societies frequently fused them, constructing elaborate cosmologies around visionary experiences.

The history of religion is filled with moments where the ingestion of a substance was itself an act of worship. The boundaries between chemical effect and spiritual encounter were not easily drawn. What mattered to the practitioners was not whether the gods existed in the mind or in the heavens, but that the veil was lifted, and the world revealed anew. In tracing this story, we encounter Mesoamerican shamans, Vedic poets, Eleusinian initiates, Amazonian healers, and Siberian visionaries, each drawing from the pharmacopeia of their land to speak with the divine.

The Ancient Near East: Scent and Smoke as Divine Language

In the ritual spaces of the Ancient Near East, hallucinatory substances were woven into the fabric of worship. The smoke of certain resins, such as frankincense and myrrh, had psychoactive effects when inhaled in concentrated settings, and temple rituals often intensified these effects through enclosed chambers.1 For priests and oracles, such states were not a loss of control but a heightening of perception, a necessary precondition for interpreting omens or speaking divine words.

There are tantalizing hints in archaeological residues from sites in Israel and Judah that cannabis may have been burned as part of temple offerings.2 This was not for secular pleasure, but a sanctified act that merged sensory disorientation with theological performance. In these settings, the chemical and the sacred were not in opposition; they were collaborators in the work of mediating between humanity and deity.

Vedic India and the Soma Mystery

In the Vedic tradition of ancient India, the hymns of the Rigveda exalted a mysterious plant-based drink known as Soma, praised as both god and offering.3 The drink induced a state of exhilaration and visionary clarity, inspiring poets and priests to compose hymns that were themselves acts of devotion. Soma was more than a ritual lubricant. It was the embodiment of immortality, consumed to draw nearer to cosmic truth.

Debates about Soma’s botanical identity, from ephedra to Amanita muscaria to a lost species altogether, have occupied scholars for centuries.4 Whatever its source, its role in religious life was unambiguous. Soma was consumed in carefully structured rites, its preparation shrouded in secrecy, its effects recorded in verse that blurred the lines between theological doctrine and psychedelic poetics. Through Soma, worshippers claimed to touch the eternal, their visions serving as both personal transformation and communal affirmation of cosmic order.

The Greek Mysteries: Eleusis and the Kykeon

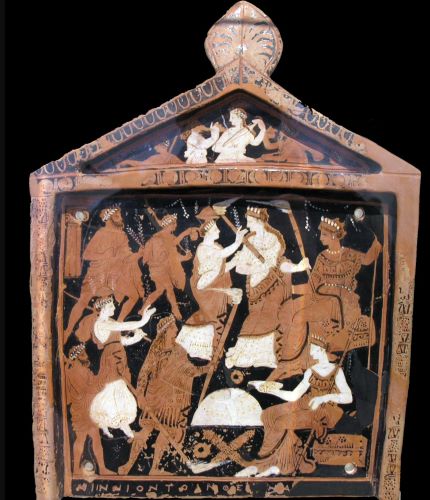

In the Greek world, the Eleusinian Mysteries stand as one of history’s most enigmatic intersections of religion and hallucinogen. At the heart of the initiation was the kykeon, a barley-based drink that scholars suspect may have contained ergot, a psychoactive fungus related to LSD.5 The ritual, lasting several days, culminated in a nocturnal revelation within the sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone.

Initiates, sworn to secrecy, spoke only of the transformation the rites brought, never revealing the precise nature of what they saw.6 Yet the pattern is suggestive: a communal ingestion, a liminal space, and the emergence from that space with the certainty of having witnessed ultimate truth. Whether or not the kykeon contained hallucinogens, its centrality to the rite and the ecstatic testimonies of participants point toward a carefully cultivated altered state. This was not intoxication as escape, but intoxication as theological encounter.

The wider Greek world also offers the example of the Delphic oracle, where the priestess Pythia delivered prophecies in a trance induced, many scholars believe, by inhaling ethylene or other intoxicating vapors seeping from the earth beneath Apollo’s temple.7 Her utterances, often cryptic and layered with poetic ambiguity, were understood as direct communication from the god. In this setting, the hallucinatory state was the medium through which divine will entered human affairs, and the chemical agent was not seen as a deception, but as the appointed instrument of revelation.

The Americas: Peyote, Ayahuasca, and the Vision Quest

Across the Americas, hallucinatory substances have played enduring roles in indigenous religious practice. In Mesoamerica, psilocybin mushrooms, called teonanácatl, “flesh of the gods,” were consumed in rituals that merged personal vision with communal renewal.8 Aztec priests used them to divine political outcomes, heal the sick, and connect with the cosmic order.

In the Amazon basin, ayahuasca, a brew combining Banisteriopsis caapi vine with DMT-containing plants, continues to serve as a sacrament among numerous tribes.9 The experience, often lasting hours, is framed not as an escape into hallucination but as a journey into the spirit world, guided by the ayahuasquero who navigates the complex visions on behalf of the participant. Farther north, the Native American Church incorporates peyote into Christian-structured services, a syncretic practice blending ancient indigenous visions with the liturgy of a newer faith.10

Among many Indigenous peoples of North America, hallucinogens were central to vision quests, solitary spiritual journeys undertaken to seek guidance, identity, or initiation into adulthood. While not all groups employed plant-based substances, some Plains and Plateau cultures used natural intoxicants such as tobacco in potent concentrations, or fasting and sleeplessness combined with plant infusions, to intensify visions. In these traditions, the altered state was framed not as an indulgence but as a disciplined trial, undertaken with ritual preparation and deep communal significance. The visions were recorded in oral histories, painted on hides, or incorporated into ceremonial regalia, ensuring that the personal revelation became part of the collective spiritual heritage.11

Siberia and the Shaman’s Flight

In the cold expanse of Siberia, shamans have long turned to Amanita muscaria, the red-capped fly agaric mushroom, to facilitate journeys into the spirit realm.12 The visions induced were not random but mapped against an established cosmology: the upper world of celestial beings, the middle world of humans, and the underworld of ancestral spirits. The shaman’s altered state was instrumental for diagnosis and healing, for recovering lost souls, and for ensuring the spiritual balance of the community.

The ritual ingestion was often accompanied by drumming, chanting, and the use of smoke to intensify the hallucinatory experience. In this context, the mushroom was not an individual escape but a communal necessity, its use validated by the efficacy of the shaman’s work. Here again, the line between chemical cause and spiritual effect was irrelevant to practitioners; what mattered was that the gods and spirits were present, and that they could be persuaded to act.

Conclusion: Altered States and the Architecture of the Sacred

From the incense-filled sanctuaries of the Near East to the hidden rites of Eleusis, from the Soma pressings of the Vedic poets to the peyote circles of the Americas, hallucinatory substances have been agents of revelation. They have shaped myths, inspired scriptures, and anchored communal identity. To participate in such rites was to enter a contract with forces beyond the ordinary, mediated through a material that both transformed the body and opened the mind.

The modern tendency to separate the sacred from the pharmacological is a historical anomaly. In much of human history, the two were bound together, each amplifying the other. Hallucinogens were not merely tools for inducing visions; they were theologically embedded acts, woven into the architecture of the sacred. The visions they brought forth were not private dreams but public affirmations of a shared cosmology, a reminder that to see the gods, one must sometimes drink, chew, or inhale the door to their world.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Terence McKenna, Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge A Radical History of Plants, Drugs, and Human Evolution (New York: Bantam, 1992), 102–104.

- Eran Arie, Baruch Rosen, and Dvory Namdar, “Cannabis and Frankincense at the Judahite Shrine of Arad,” Tel Aviv 47, no. 2 (2020): 5-28.

- Wendy Doniger, The Rig Veda: An Anthology (London: Penguin, 1981), 45–50.

- David Flattery and Martin Schwartz, Haoma and Harmaline: The Botanical Identity of the Indo-Iranian Sacred Hallucinogen “Soma” and Its Legacy in Religion, Language, and Middle Eastern Folklore (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 19–23.

- Carl A. P. Ruck, et.al., The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1998), 12–15.

- Walter Burkert, Ancient Mystery Cults (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), 276–281.

- Jelle Zeilinga de Boer and John R. Hale, “The Geological Origins of the Oracle at Delphi, Greece,” Geological Society, Lond, Special Publications 171 (2000): 199-412.

- R. Gordon Wasson, “The Hallucinogenic Mushrooms of Mexico: An Adventure in Ethnomycological Exploration,” Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences 21:4-II (1959): 332.

- Michael Winkelman, Shamanism: A Biopsychosocial Paradigm of Consciousness and Healing (Westport: Bergin & Garvey, 2000), 125–127.

- Omer C. Stewart, Peyote Religion: A History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 198–203.

- Joseph Epes Brown, The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk’s Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953), 46–52.

- Marlene Dobkin de Rios, Hallucinogens: Cross-Cultural Perspectives (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984), 89–92.

Bibliography

- Arie, Eran, Baruch Rosen, and Dvory Namdar. “Cannabis and Frankincense at the Judahite Shrine of Arad.” Tel Aviv 47, no. 2 (2020): 1–15.

- Brown, Joseph Epes. The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk’s Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953.

- Burkert, Walter. Ancient Mystery Cults. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

- de Boer, Jelle Zeilinga, and John R. Hale. “The Geological Origins of the Oracle at Delphi, Greece.” Geological Society, Lond, Special Publications 171 (2000).

- Dobkin de Rios, Marlene. Hallucinogens: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

- Doniger, Wendy. The Rig Veda: An Anthology. London: Penguin, 1981.

- Flattery, David, and Martin Schwartz. Haoma and Harmaline: The Botanical Identity of the Indo-Iranian Sacred Hallucinogen “Soma” and Its Legacy in Religion, Language, and Middle Eastern Folklore. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

- McKenna, Terence. Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge A Radical History of Plants, Drugs, and Human Evolution. New York: Bantam, 1992.

- Ruck, Carl A. P. et.al. The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1998.

- Stewart, Omer C. Peyote Religion: A History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

- Wasson, R. Gordon. “The Hallucinogenic Mushrooms of Mexico: An Adventure in Ethnomycological Exploration.” Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences 21:4-II (1959): 325-339.

- Winkelman, Michael. Shamanism: A Biopsychosocial Paradigm of Consciousness and Healing. Westport: Bergin & Garvey, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.