The historical context and the actual impact of voucher programs.

By Chris Ford

Commissioner of General Services

Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government (LFUCG)

By Stephenie Johnson

Program Director

The Learning Agency

By Lisette Partelow

Senior Fellow

Center for American Progress

Introduction

About three and a half hours southwest of Washington, D.C., nestled in the rolling hills of the Virginia Piedmont is Prince Edward County, a rural community that was thrust into the history books more than 60 years ago when county officials chose to close its segregated public schools rather than comply with court-mandated desegregation following the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision.1 Like many public school districts in the South during the Jim Crow era, Prince Edward County operated a segregated school system—a system white officials and citizens were determined to keep by any means necessary. The scheme they hatched was to close public schools and provide white students with private school vouchers.

Fast forward to 2017: President Donald Trump and U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos have championed a plan to provide federal funding for private school voucher systems nationwide, which would funnel millions of taxpayer dollars out of public schools and into unaccountable private schools—a school reform policy that they say would provide better options for low-income students trapped in failing schools. Their budget proposal would slash the Education Department’s budget by more than 13 percent, or $9 billion, while providing $1.25 billion for school choice, including $250 million for private school vouchers.2

When pressed on the risks and unintended consequences of potential exclusionary policies in voucher programs, Secretary DeVos refused to commit to aggressively enforce civil rights protections. In May of 2017 in her testimony before the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies, Betsy DeVos declined to say whether she would protect students against discriminatory policies in private schools that receive federal funding through vouchers.3

As Americans debate this issue on the national level, they must consider both the historical context and the actual impact of voucher programs.

Sordid History of School Vouchers

During Jim Crow—when state and local laws enforced racial segregation—Prince Edward County operated two high schools: the well-funded Farmville High School for white children and the severely underfunded Robert Russa Moton High School for black children. The latter was not only overcrowded but also lacked a cafeteria, a gymnasium, a locker room, and a proper heating system.4 The alarming differences between the schools and the anger the situation engendered in the black community reached a boiling point when black students, led by upperclassman Barbara Johns, organized a strike at Moton to demand equal facilities.5 Their strike attracted the attention of the state’s NAACP lawyers, who filed suit in 1951 against the County in Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County. The plaintiffs in Davis, along with others in NAACP school desegregation suits filed in Clarendon County, South Carolina; New Castle County, Delaware; and in Washington, D.C., would eventually be added under the umbrella of a larger desegregation case headlined by Topeka, Kansas’ Brown v. Board of Education.6

When the U.S. Supreme Court gave its initial ruling for Brown in May 1954, the court deemed separate but equal unacceptable in public education. The negative reaction to the Brown ruling by many white residents in Prince Edward County, in Virginia, and in much of the rest of the South, coalesced in what became known as “massive resistance.”7 Led by Harry Byrd, the U.S. senator representing Virginia, massive resistance was a movement against federally mandated integration, particularly in public schools. Byrd’s plan allowed for Virginia to flex the power of the purse in deciding who could receive a quality public education. The state Legislature passed a law allowing it to revoke funds from and even close districts and schools that integrated black and white students, leading to school closures in Charlottesville and Norfolk.8

White citizens in Prince Edward County were committed to operating a segregated school system and took even more aggressive measures. First, the county board of supervisors slashed funds for its public schools to $150,000, the minimum amount legally required in 1955—$550,000 less than the nearly $700,000 requested by the county school board.9 Along with allocating fewer funds for the County’s schools, supervisors also voted to switch how often they would distribute those funds, changing the schedule from an annual basis to a monthly basis.

When school funds were distributed annually, the district was committed to keeping the school open for the length of the school year. In contrast, a monthly distribution schedule gave the County greater flexibility to close schools abruptly and minimize the financial loss. Threatened with having to integrate their schools, the County could simply choose not to give out the remaining funds, close the schools, and subsequently save tax dollars and achieve their goal of not paying for integrated schools. Ultimately, Prince Edward County chose to close its entire public school system in 1959 rather than operate integrated schools.10

The original 1954 Brown ruling, as definitive as it was for civil rights, simply did not have the teeth to force unwilling communities to desegregate their schools. The Brown II ruling, which came just a year later, called for districts to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”11 While the ruling called for more urgent action from districts to desegregate their schools, the ambiguity of the phrase provided ample leeway for officials such as those in Prince Edward County to implement delaying tactics.12 In fact, in the years following the Brown rulings, Virginia’s NAACP chapter continuously fought county officials in court as they refused to set a start date for integrating the public schools.

Finally, in September 1959, the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the County to “take immediate steps” toward integrating its schools, bringing the situation in the County to a breaking point.13 The county board of supervisors, with assistance from the Virginia General Assembly, took additional measures to undermine funding for integrated public schools. The board decided not to levy local taxes for the 1959-60 school year, eliminating a major source of funding for its schools. Meanwhile, the state adopted a new voucher system called a “tuition grant program,” offering students vouchers of $125 for elementary school students and $150 for high schoolers to attend a nonsectarian private school or a public school in nearby localities.14 During this same period, private citizens began raising funds to build and operate a private school to educate the County’s white children in the event the public schools were closed.15

The final measure taken by the county board of supervisors was to close public schools in Prince Edward County. The magnitude of the decision was unprecedented. While the state Legislature had the authority to close individual schools, it had only done so on three occasions at individual schools in Charlottesville, Norfolk, and Warren County.16 By closing its entire public school system, Prince Edward County had taken Harry Byrd’s massive resistance plan to the extreme.

When the County locked and chained its schools’ doors in September 1959, defying the court’s mandate to integrate them, white children continued their education at the private Prince Edward Academy, a “segregation academy” that would serve as a model for other communities in the South.17 The County’s black students, however, were not permitted to attend Prince Edward Academy nor granted tuition grants to attend other private schools. Ultimately, their options for continued education were stymied by several factors, including state laws that still permitted segregation of public schools; tuition grants from the state that they could not use; and the state’s Pupil Placement Board, which effectively prevented black students from attending white schools in other communities.18

Thus, black parents were forced to go to incredible lengths to educate their children. Those who could do so moved their children across state lines to North Carolina, where Kittrell Junior College accommodated about 60 students.19 Others relocated their children northward to the homes of relatives, to states with integrated schools, or into the homes of Quakers who were a part of the American Friends Service Committee.20 Some community members cobbled together informal educational opportunities, particularly for younger children. The worst-case scenario, of course, was leaving the education system altogether—the path followed by many older children on the cusp of adulthood.

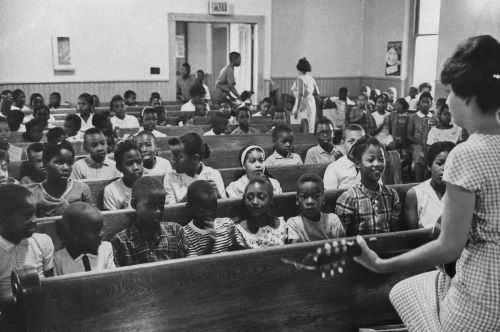

The situation in Prince Edward County finally reached the attention of the Kennedy administration by the summer of 1963. Then-U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy would dispatch officials from the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) to the County in order to assess how the federal government could help.21 In a summer of student protests against the continued closures, black and white leaders in the County finally landed on a plan to temporarily operate free private schools for black students. White students, should they wish to, were also permitted to attend the school. Private donations helped fund the million-dollar price tag need to operate the Prince Edward Free Schools, with donations coming from the Ford Foundation, the Field Foundation, and the National Education Association.22

In 1964, the Supreme Court ruled in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County that the County had to reopen its public schools on the grounds that it was still in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.23 By closing its public schools and subsequently subsidizing private academies that only admitted white students, the County, along with the state board of education and state superintendent, continued to deny black students the rights their white peers were provided. Even with the reopening of the County’s public schools following the Griffin ruling, segregation supported by a voucher system and inequitable funding persisted.24 The County’s board of supervisors devoted only $189,000 in funding for integrated public schools.25 At the same time, they allocated $375,000 that could effectively only be used by white students for “tuition grants to students attending either private nonsectarian schools in the County or public schools charging tuition outside the County.”26

In 1965, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District in Virginia found in Griffin v. State Board of Education that vouchers from the state’s tuition grant program could not lawfully be used to fund schools that discriminate based on race.27 While not citing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as a legal basis for its ruling, the court nonetheless relied on the law’s definition of a public school—any institution that was “operated wholly or predominantly from or through the use of governmental funds or property.”28

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which barred federal funds from going to segregated schools, made it clear that Prince Edward County could not continue their practices legally and receive federal funding.29 This law, as well as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, was instrumental in elevating the role of the federal government in protecting students from discrimination in the nation’s public schools. From a legal perspective, these rulings and federal laws put an end to the legitimacy of massive resistance, but the effects of the County’s practices throughout the 1950s would continue to affect the student population for decades.

Echoes of a Segregated Past

Despite legal segregation being outlawed, Prince Edward County’s students still faced de facto segregation in the years following massive resistance and the decision to close the public schools. The County and state’s support of policies that facilitated white flight to private academies allowed for a disproportionate number of black and white students to be enrolled in the County’s schools compared to the County’s population.30 In the 1971-72 school year, only 5 percent of students in the County’s K-12 public schools were white.31

That demographic mismatch between the County and its public school system persists today. According to data from the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia, demographics for Prince Edward County show that in 2015, white residents comprised 64 percent of the County’s approximately 23,000 residents, while black residents comprised only 32 percent.32 However, in the 2013-14 school year, the most recent year with available data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the County’s public schools enrolled 2,282 students, 37 percent of whom were white and 56 percent of whom were black.33

Despite the 1965 ruling that ended the voucher program in the County and state, de facto segregation also persisted for decades at the private Prince Edward Academy—now named the Fuqua School—the original “segregation academy” founded in the County in 1959.34 In 1980, the school decided to admit black students to keep their tax-exempt status but kept the black student population to a mere 1 percent—or seven out of 640 students.35 The school would not graduate a black student until the 1989-90 school year, and its black enrollment was still under 5 percent in 2013 with only 17 black students among its enrollment of 362.36

Prince Edward County’s actions following Brown in 1954 provided the blueprint for many Southern communities as they devised plans to divert and use public money to establish private schools that catered exclusively to white families. Segregationists in the County, many of whom occupied positions of power, believed their cause to be courageous and knew that it could set a precedent for other communities unwilling to desegregate their public schools.37

By 1969, more than 200 private segregation academies were set up in states across the South.38 Seven of those states—Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana—maintained tuition grant programs that offered vouchers to students in an effort to incentivize white students to leave desegregated public school districts.39 Between the 1969-70 and the 1970-71 school years, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi saw tens of thousands of students flee to newly opened segregation academies.40 In a single school year, Mississippi led the trio with almost 41,000 students having left the state’s public schools. Alabama saw 21,565 students unenroll from its public schools, while Louisiana had more than 11,000 students.41

The rise of private schools in the South and the diversion of public funds to those private schools through vouchers was a direct response of white communities to desegregation requirements.42 In Louisiana, the state established the Louisiana Financial Assistance Commission, which offered vouchers of $360 for students attending private school but only provided $257 per student to those attending public schools.43 Over the commission’s lifespan, the state devoted more than $15 million in vouchers through its tuition grant program, with the initial $2.5 million coming from Louisiana’s Public Welfare Fund. A 1958 state law also allowed school districts to close their public schools and sell or lease their resources for considerably less than their value for use by private schools.44

Vouchers used from Mississippi’s tuition grant program followed a similar path and pattern. In 1969, the U.S. DOJ intervened for the plaintiffs who sued the state of Mississippi in Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission.45 In the five years before the case made it to the Supreme Court, the state offered vouchers for students to exercise “individual freedom in choosing public or private school,” which provided them with the opportunity to choose to attend racially segregated schools.46 Originally only offering $180 per student in 1964, the state Legislature increased the amount of each voucher to be $240 per student in 1968.47

In detailing the program’s existence, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi found that segregation academies in the state were consistently established in public school districts that had either recently been forced to desegregate by the courts or had recently submitted desegregation plans.48 Appendix B of the court’s ruling reveals the percentage of tuition that was covered by the vouchers offered to students at a number of the state’s segregation academies. On the low end of the spectrum, the state’s $240 voucher only covered 17 percent of Gulf Coast Mill Academy’s $1,395 tuition. On the high end, however, 96 percent of tuition was covered at schools such as Adams County Private School and Deer-Creek Educational Institute.

Not only did the court find that the state was subsidizing large portions of these school’s budgets, it also found that the state’s payment of the grants frequently coincided with dates on which tuition was due at the schools. Ultimately, as was the case in Griffin for Prince Edward County and Virginia, the court found Mississippi’s tuition grant scheme to be in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, as it “significantly encourage[d] and involve[d] the State in private discriminations.”49

Alabama also enacted tuition grant state laws permitting students to use vouchers at private schools in the mid-1950s, while also enacting nullification statutes against court desegregation mandates and altering its teacher tenure laws to allow the firing of teachers who supported desegregation.50 Alabama’s tuition grant laws would also come before the court, with the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama declaring in Lee v. Macon County Board of Education vouchers to be “nothing more than a sham established for the purpose of financing with state funds a white school system.”51

White flight from public schools to segregation academies in Alabama had devastating effects on districts’ abilities to raise funds. As more white students left the public system, white taxpayers became reluctant to raise property taxes to fund their public schools. Authors of a study looking at the effects of Alabama’s mid-century school choice policies found that when communities have dual school systems—that is to say, a public and a private system—taxpayers are significantly less inclined to fund the public system.52

Efforts to remedy Alabama’s funding inequities, which disproportionately affected black students and students with disabilities, showed promise in the early 1990s as state courts declared that conditions in Alabama’s poorest schools violated the state constitution by failing to provide all children with an adequate education.53 Those remedies would fall short of being realized when Jeff Sessions, the then-Alabama attorney general—now the current U.S. attorney general—led a campaign against the state judiciary. Despite the courts having played an integral role in serving as a check against states not acting in the interests of all students for nearly four decades, Sessions’ campaign against judicial oversight of legislative actions prevented the judiciary from resolving inequities in the Alabama education system.54

School Funding Inequities and Growing Segregation a Trend of Vouchers

The trend of increasing racial and economic segregation is a nationwide trend—not just in Alabama and other Southern states.55 The South, however, was the only region in the country to see a net increase in private school enrollment between 1960 and 2000, and where private school enrollment is higher, support for spending in public schools tends to be lower.56 A growing body of rigorous research shows that money absolutely matters for public schools, especially for the students from low-income families who attend them.57 What’s more, private schools in the South tend to have the largest overrepresentation of white students.58 In fact, research has shown that the strongest predictor of white private school enrollment is the proportion of black students in the local public schools.59

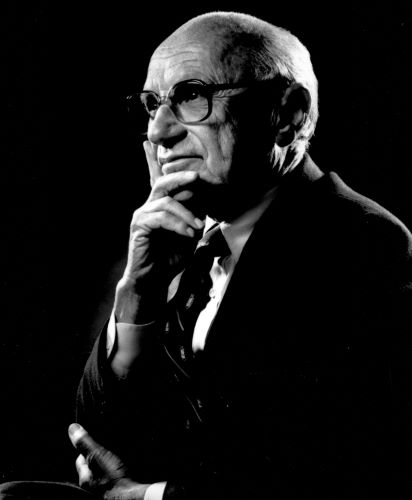

Modern-day voucher advocates often cite economist Milton Friedman as the visionary of today’s programs. Friedman published “The Role of Government in Education” in 1955, an essay in which he argued that—while governments have a vested interest in educating the nation’s children to ensure an informed and engaged citizenry and functioning democracy—they should not necessarily be directly involved in providing such an education.60 He believed that a privatized system in which the government provides funds for all children to receive a basic education at a school of choice would better meet the needs of parents and students. Friedman even posited that “mixed schools” in this system could grow at the expense of racially segregated private schools.

Today, voucher programs vary greatly in design and eligibility criteria. Almost all prioritize access for low-income students though some are eligible to all students regardless of their financial means. And even contemporary race-neutral voucher programs can have the effect of exacerbating racial and socio-economic segregation. A recent analysis by The Century Foundation demonstrated that voucher programs tend to benefit the most advantaged students eligible for the programs.61 Widespread enactment of private school choice in other nations such as Sweden and Chile has led to increasingly economically segregated schools.62

Chile’s voucher program has led to widespread socio-economic stratification and a decline in public school enrollment, all while making little to no impact on student achievement.63 The program’s design essentially creates three school systems: public schools attended mostly by the lowest-income students; voucher-subsidized private schools attended by more middle-class students, as they can charge additional fees or tuition; and nonsubsidized private schools attended by the wealthiest students. This design—and the relatively small number of private schools in rural communities—has greatly contributed to this socio-economic segregation.64 Such policies, if adopted nationally in the United States, could have similar consequences for economic and racial segregation considering the strong correlation between race and income in many places.

Indiana’s voucher program provides a case study for how voucher programs may benefit one group of students over another. Recently, NPR reported that Indiana’s statewide voucher program increasingly benefits white, suburban, middle-class families more than the low-income students in underperforming schools whom the program was originally intended to serve.65 Today, around 60 percent of voucher recipients come from white families, an increase of 14 percent since the program’s inception in 2013. The percentage of black students receiving vouchers has dropped to 12 percent, down from 24 percent in 2013. Furthermore, NPR’s investigative report notes that more than 50 percent of the students enrolled in the voucher program have never attended a public school.66

While there is no indication of racial motivation among the Indiana lawmakers who created the voucher program, the effects are clear: Indiana’s voucher program increasingly benefits higher-income white students, many of whom are already in private schools, and diverts funding from all other students who remain in the public school system.

Conclusion

The impacts of the first private school voucher programs in the South still reverberate today in battles for adequate and equitable funding of public education. And when President Trump nominated Betsy DeVos—a longtime Republican donor with a passion for private school vouchers—to become the next secretary of education, he elevated vouchers to the forefront of the national policy conversation.67 Swiftly thereafter, Trump and DeVos proposed to cut billions in funding for public schools while creating the first nationwide federal private school vouchers program.68 What’s more, in May 2017, while defending the Trump budget before the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies, DeVos refused to say that the Department of Education, under her leadership, would protect students against all forms of discrimination in private schools that receive federal taxpayer dollars through vouchers.69

Moreover, both Trump and DeVos have a worrying pattern of denying or ignoring history. In February, DeVos referred to historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) as “real pioneers when it comes to school choice,” failing to mention that these institutions emerged to serve black students who were being shut out of institutions of higher education that were discriminating against them.70 And President Trump has also shown a lack of appreciation for the history of racism in the country.71

Voucher schemes—such as those backed by President Trump and Secretary DeVos—are fundamentally positioned to funnel taxpayers’ dollars into private schools while draining much-needed resources from public schools and the vulnerable students who attend them. Policymakers must consider the origins of vouchers and their impact on segregation and support for public education. No matter how well intentioned, widespread voucher programs risk exacerbating segregation in schools and leaving the most vulnerable students and the public schools they attend behind.

Endnotes

- National Archives, Educator Resources, “Order of Argument in the Case, Brown v. Board of Education,” available at https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/brown-case-order (last accessed July 2017); Kristen Green, Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2015).

- Scott Sargrad, “An Attack on American’s Schools,” U.S. News & World Report, May 23, 2017, available at https://www.usnews.com/opinion/knowledge-bank/articles/2017-05-23/donald-trump-and-betsy-devos-budget-would-destroy-public-schools; Stephenie Johnson and others, “The Trump-DeVos Budget Would Dismantle Public Education, Hurting Vulnerable Kids, Working Families, and Teachers,” Center for American Progress, March 17, 2017, available at https://americanprogress.org/issues/education/news/2017/03/17/428598/trump-devos-budget-dismantle-public-education-hurting-vulnerable-kids-working-families-teachers/.

- CAP Action, “The 3 Most Outrageous Things Betsy DeVos Said While Defending the Disastrous Trump FY 2018 Budget,” Medium, May 24, 2017, available at https://medium.com/@CAPAction/the-3-most-outrageous-things-betsy-devos-said-while-defending-the-disastrous-trump-fy-2018-budget-f8a25271ade0.

- Kara Miles Turner, “Both Victors and Victims: Prince Edward County, Virginia, the NAACP, and ‘Brown,’” Virginia Law Review 90 (6) (2004): 1667–1691.

- Michael W. Fuquay, “Civil Rights and the Private School Movement in Mississippi, 1964-1971,” History of Education Quarterly 42 (2) (2002): 159–180; Robert Russa Moton Museum, “Biography: Barbara Rose Johns Powell,” available at http://www.motonmuseum.org/biography-barbara-rose-johns-powell/ (last accessed July 2017).

- National Archives, Educator Resources, “Order of Argument in the Case, Brown v. Board of Education.”

- Virginia Historical Society, “Massive Resistance,” available at http://www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/civil-rights-movement-virginia/massive (last accessed July 2017).

- Ibid.

- Turner, “Both Victors and Victims.”

- Ibid.

- Justia, U.S. Supreme Court, “Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294 (1955),” available at https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/349/294/case.html (last accessed July 2017).

- Virginia Historical Society, “Brown I and Brown II,” available at http://www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/civil-rights-movement-virginia/brown-i-and-brown (last accessed July 2017).

- The New York Times, “Text of Supreme court’s Decision ordering Virginia County to Reopen Its Schools,” May 26, 1964, available at http://www.nytimes.com/1964/05/26/text-of-supreme-courts-decision-ordering-virginia-county-to-reopen-its-schools.html?_r=0.

- Justia, U.S. Law, “Griffin v. State Board of Education, 239 F. Supp. 560 (E.D. Va. 1965),” available at http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/239/560/2379198/ (last accessed July 2017).

- Green, Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County.

- Virginia Historical Society, “Massive Resistance.”

- Margaret E. Hale-Smith, “The Effect of Early Educational Disruption on the Belief Systems and Educational Practices of Adults: Another Look at the Prince Edward County School Closings,” The Journal of Negro Education 62 (2) (1993): 171–189.

- Sara Kathryn Eskridge, “Virginia’s Pupil Placement Board and the Massive Resistance Movement, 1956-1966,” Master of Arts dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2006, available at http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1819&context=etd.

- Hale-Smith, “The Effect of Early Educational Disruption on the Belief Systems and Educational Practices of Adults.”

- Turner, “Both Victors and Victims.”

- Green, Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County.

- Ibid.

- The New York Times, “Text of Supreme court’s Decision ordering Virginia County to Reopen Its Schools.”

- Ibid.

- Turner, “Both Victors and Victims.”

- Ibid.

- Justia, U.S. Law, “Griffin v. State Board of Education.”

- Ibid.

- Eskridge, “Virginia’s Pupil Placement Board and the Massive Resistance Movement, 1956-1966”; Virginia Historical Society, “Passive Resistance,” available at http://www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/civil-rights-movement-virginia/passive (last accessed July 2017).

- Wilbur B. Brookover, “Education in Prince Edward County, Virginia, 1953-1993,” The Journal of Negro Education 62 (2) (1993): 149–161.

- Ibid.

- University of Virginia Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, “Population Estimates for Age & Sex, Race & Hispanic, and Towns,” available at http://demographics.coopercenter.org/population-estimates-age-sex-race-hispanic-towns/ (last accessed July 2017).

- National Center for Education Statistics, “ELSi Table Generator: Race/Ethnicity enrollment data for Prince Edward County Public Schools for the 2013-14 school year,” available at https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/elsi/tableGenerator.aspx (last accessed July 2017) .

- Brookover, “Education in Prince Edward County, Virginia, 1953-1993.”

- Ibid.

- National Center for Education Statistics, “Private School Universe Survey: Fuqua School,” available at https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pss/privateschoolsearch/school_detail.asp?Search=1&SchoolName=fuqua&City=farmville&State=51&NumOfStudentsRange=more&IncGrade=-1&LoGrade=-1&HiGrade=-1&ID=01434161 (last accessed July 2017).

- J. Michael Utzinger, “The Tragedy of Prince Edward: The Religious Turn and the Destabilization of One Parish’s Resistance to Integration, 1963-1965,” Anglican and Episcopal History 82 (2) (2013): 129–165.

- Time, “Private Schools: The Last Refuge,” November 14, 1969, available at http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,840365,00.html.

- Helen Hershkoff and Adam S. Cohen, “School Choice and the Lessons of Choctaw County,” Yale Law & Policy Review 10 (1) (1992): 1–29.

- Robert E. Anderson Jr., “The South and Her Children: School Desegregation, 1970-1971” (Atlanta: Southern Regional Council, 1971), available at http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED049327.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Fuquay, “Civil Rights and the Private School Movement in Mississippi, 1964–1971.”

- Justia, U.S. Law, “Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Commission, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1968),” available at http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/275/833/1458865/ (last accessed July 2017).

- Hershkoff and Cohen, “School Choice and the Lessons of Choctaw County.”

- Justia, U.S. Law, “Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission, 296 F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss. 1969),” available at http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/296/1389/1982533/ (last accessed July 2017).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Hershkoff and Cohen, “School Choice and the Lessons of Choctaw County.”

- Justia, U.S. Law, “Lee v. Macon Country Board of Education, 267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1967),” available at http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/267/458/1895721/ (last accessed July 2017).

- Hershkoff and Cohen, “School Choice and the Lessons of Choctaw County.”

- Ryan Gabrielson, “How Jeff Sessions Helped Kill Equitable School Funding in Alabama,” ProPublica, January 30, 2017, available at https://www.propublica.org/article/how-jeff-sessions-helped-kill-equitable-school-funding-in-alabama.

- Ibid.

- Halley Potter, Kimberly Quick, and Elizabeth Davies, “A New Wave of School Integration: Districts and Charters Pursuing Socioeconomic Diversity” (Washington: The Century Foundation, 2016), available at https://tcf.org/content/report/a-new-wave-of-school-integration/.

- Charles T. Clotfelter, “Private Schools, Segregation, and the Southern States,” Peabody Journal of Education 79 (2) (2004): 74–97; Hershkoff and Cohen, “School Choice and the Lessons of Choctaw County.”

- Ulrich Boser, “Money Clearly Matters,” U.S. News & World Report, March 17, 2016, available at https://www.usnews.com/opinion/knowledge-bank/articles/2016-03-17/why-money-matters-for-low-income-schools; C. Kirabo Jackson, Rucker C. Johnson, and Claudia Persico, “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms.” Working Paper 20847 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015).

- Southern Education Foundation, “Race and Ethnicity in a New Era of Public Funding of Private Schools: Private School Enrollment in the South and the Nation” (2016), available at http://www.southerneducation.org/PubliclyFundedPrivateSchoolSegregation.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, Halley Potter, and Kimberly Quick, “Why Private School Vouchers Could Exacerbate School Segregation,” The Century Foundation, December 19, 2016, available at https://tcf.org/content/commentary/private-school-vouchers-exacerbate-school-segregation/.

- Milton Friedman, “The Role of Government in Education” (Austin, Texas: The University of Texas at Austin, 1955), available at http://la.utexas.edu/users/hcleaver/330T/350kPEEFriedmanRoleOfGovttable.pdf.

- Kahlenberg, Potter, and Quick, “Why Private School Vouchers Could Exacerbate School Segregation.”

- Ray Fisman, “Sweden’s School Choice Disaster,” Slate, July 15, 2014, available at http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/the_dismal_science/2014/07/sweden_school_choice_the_country_s_disastrous_experiment_with_milton_friedman.html; Amaya Garcia, “Chile’s School Voucher System: Enabling School Choice or Perpetuating Social Inequality?”, New America, February 9, 2017, available at https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/chiles-school-voucher-system-enabling-choice-or-perpetuating-social-inequality/.

- Alejandra Mizala and Florencia Torche, “Bringing the Schools Back in: The Stratification of Educational Achievement in the Chilean Voucher System” International Journal of Educational Development 32 (1) (2012): 1–13.

- Ibid; Garcia, “Chile’s School Voucher System.”

- Cory Turner, Eric Weddle, and Peter Balonon-Rosen, “The Promise And Peril Of School Vouchers,” National Public Radio, May 12, 2017, available at http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2017/05/12/520111511/the-promise-and-peril-of-school-vouchers?utm_source=twitter.com&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=npred&utm_term=nprnews&utm_content=20170512 (last accessed July 2017).

- Ibid.

- Ulrich Boser, Marcella Bombardieri, and CJ Libassi, “Conflicts of DeVos: Donald Trump, Betsy DeVos, and a Pay-to-Play Nomination” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2017), available at https://americanprogress.org/issues/education/news/2017/01/12/296231/conflicts-of-devos/; Joy Resmovits, “Trump’s pick for Education secretary could put school vouchers back on the map,” Los Angeles Times, January 16, 2017, available at http://www.latimes.com/local/education/la-me-trump-vouchers-california-20161221-story.html.

- U.S. Department of Education, “President’s FY 2018 Budget Request for the U.S. Department of Education,” available at https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/budget/budget18/index.html(last accessed July 2017).

- CAP Action, “The 3 Most Outrageous Things Betsy DeVos Said While Defending the Disastrous Trump FY 2018 Budget.”

- Danielle Douglas-Gabriel and Tracy Jan, “DeVos called HBCUs ‘pioneers’ of ‘school choice.’ It didn’t go over well,” The Washington Post, February 28, 2017, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2017/02/28/devos-called-hbcus-pioneers-of-school-choice-it-didnt-go-over-well/?utm_term=.c1e318cf5429.

- David A. Graham, “Donald Trump’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” The Atlantic, February 1, 2017, available at https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/02/frederick-douglass-trump/515292/.

Originally published by Center for American Progress, 07.12.2017, republished with permission educational, for non-commercial purposes.