By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the vast expanse of Chinese legend, few tales capture the imagination as vividly as that of Wan Hu, the alleged 16th-century Ming dynasty official who sought to escape the pull of Earth by strapping rockets to a chair in the earliest mythical attempt at human spaceflight. Though the story is apocryphal, Wan Hu occupies a curious space between history, folklore, and aspiration. His ambition—to rise above the Earth and breach what modern science understands as the planet’s protective atmospheric shell—reflects a longstanding human yearning to transcend earthly limitation. While no contemporary historical records directly document Wan Hu’s alleged experiment, the story’s persistence through centuries offers insight into early conceptions of technology, celestial aspiration, and the metaphorical power of human daring.

Here I explore Wan Hu’s legendary attempt within the context of early Chinese scientific imagination, the development of rocketry, and the philosophical significance of breaching the atmospheric barrier. Although factually tenuous, the legend of Wan Hu represents an embryonic form of the same spirit that drove modern cosmonauts and astronauts beyond the clouds.

The Legend of Wan Hu

The tale of Wan Hu first gained widespread attention in the West through 20th-century retellings, particularly in American publications during the post–World War II rocket age. According to the legend, Wan Hu was a mid-ranking Chinese official fascinated by astronomy and alchemy. Obsessed with the stars and the moon, he allegedly devised a scheme to ascend to the heavens by attaching 47 gunpowder rockets to a wooden chair, flanked by two assistants with torches to ignite them simultaneously. Upon ignition, a massive explosion was said to follow—after which Wan Hu disappeared without a trace. In some versions, he perished in the attempt; in others, he soared into the sky, never to return.

No authoritative Chinese source from the Ming period mentions Wan Hu. The tale appears to be an embellishment—possibly originating as a parable or satirical anecdote—revived and reframed during the early 20th-century fascination with rocketry. In 1945, the American writer Herbert S. Zim included the story in his book Rockets and Jets, contributing to its popularity in modern culture and cementing Wan Hu’s image as a proto-astronaut of antiquity.1

Despite its dubious historicity, the myth resonates symbolically. It positions Wan Hu as a kind of Icarus of the East, one who dared to breach the sky’s limits, and whose ambition mirrors modern efforts to pierce Earth’s atmospheric envelope.

Early Chinese Rocketry and Technological Foundations

While Wan Hu’s specific experiment is likely apocryphal, the technological foundation for such a legend was present in China centuries before the modern era. China is credited with inventing black powder (gunpowder) in the 9th century, and by the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), the military was already using rocket-propelled arrows in warfare.2 These “fire arrows” were an early form of solid-fuel rocketry. Over time, such devices were refined and used not only in battle but also in ceremonial displays.

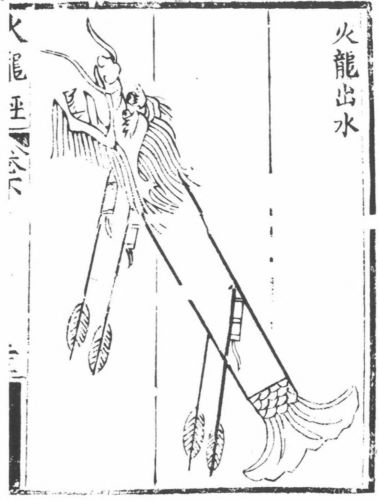

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644), in which Wan Hu is said to have lived, was a period of intense innovation. Military treatises such as the Huolongjing (Fire Dragon Manual), attributed to Jiao Yu, detailed the construction of various rocket-based weapons, including multistage rockets and aerodynamic designs.3 The idea of using black powder propulsion to achieve upward motion was thus not outside the imagination of the time—though practical understanding of physics, pressure, and thrust was still rudimentary.

What the tale of Wan Hu mythologizes, then, is the fusion of existing technology with visionary purpose. The story is not merely one of rocket experimentation; it is the dramatization of a mind attempting to ascend past the earthly domain—one that points symbolically toward what we now call escape velocity and the breaching of Earth’s thermospheric boundary, the outermost layer where atmospheric drag becomes negligible.

Breaching Earth’s Atmospheric Shell: The Scientific Threshold

In modern aerospace science, Earth’s atmosphere is divided into layers—the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere, and exosphere. The term “atmospheric shell” is a useful metaphor for describing this protective envelope, which shields life from solar radiation, meteors, and the vacuum of space. Breaching this shell requires not only altitude but velocity—about 11.2 kilometers per second to escape Earth’s gravity.4

Wan Hu’s rockets, based on gunpowder, would have lacked both the thrust and the structural engineering to achieve such a feat. Nevertheless, the symbolism of atmospheric breach embedded in the legend is compelling. In ancient cosmology, the sky was often considered a divine realm, a celestial vault separating the mortal world from the heavens. To attempt to break through this boundary—whether with rockets, wings, or alchemy—was to challenge the limits of human domain.

What Wan Hu metaphorically represents is a proto-modern confrontation with the limits of nature. His failure—or disappearance—mirrors our historical process of trial, error, and tragic consequence in pursuit of space exploration. Just as early 20th-century pioneers like Robert Goddard faced ridicule for pursuing rocketry, Wan Hu’s story might be read as a pre-scientific expression of that same longing, cast in a mythic form.

Myth, Memory, and the Proto-Astronaut

In 2004, NASA commemorated Wan Hu’s place in spacefaring mythology by naming a lunar crater “Wan-Hoo” in his honor.5 This gesture, though lighthearted, reflects a deeper recognition: humanity’s pursuit of space is as much about narrative and identity as it is about science. The desire to “touch the stars” is embedded in our collective psyche, and stories like that of Wan Hu serve to anchor modern achievements in a lineage of ancient dreams.

Moreover, the story provides a cross-cultural bridge. Western space narratives often trace their origins to figures like Jules Verne or Goddard, but the legend of Wan Hu allows non-Western cultures to claim ancestral connection to the great arc of space exploration. He becomes a symbol not of scientific success, but of cosmic aspiration—a figure who points forward to Tsiolkovsky, Korolev, von Braun, and beyond.

In this way, Wan Hu embodies more than mere myth. He is a cipher through which we explore the boundaries between knowledge and imagination, between failure and ambition, between Earth and sky. To “breach Earth’s atmospheric shell” is, in the Wan Hu narrative, both a literal and metaphorical act: a launch toward transcendence.

Conclusion

While Wan Hu likely never lived—or if he did, never attempted a rocket launch—the tale of his ascent (and presumed demise) continues to resonate. It reveals the timelessness of humanity’s desire to escape earthly confines and penetrate the boundaries of the known world. In a time before Newtonian mechanics or thermodynamic equations, Wan Hu’s imagined chair of rockets stands as a monument to imagination’s power to foreshadow what science might one day make real. The atmospheric shell that now seems so permeable to the International Space Station or Mars-bound probes was, in Wan Hu’s age, a boundary of mythic scale. To breach it—even in legend—was a profound act of symbolic rebellion against gravity, nature, and limitation itself. And in that sense, Wan Hu flies not in rockets, but in the human soul.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Herbert S. Zim, Rockets and Jets (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1945), 9–10.

- Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5, pt. 7: Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 81–83.

- Ibid., 135.

- Edward L. Dreyer, Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433 (New York: Pearson Longman, 2007), 19.

- NASA, “International Astronomical Union Lunar Nomenclature: Wan-Hoo,” Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, accessed July 7, 2025, https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov.

Bibliography

- Dreyer, Edward L. Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman, 2007.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Zim, Herbert S. Rockets and Jets. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1945.

- NASA. “International Astronomical Union Lunar Nomenclature: Wan-Hoo.” Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. Accessed July 7, 2025. https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.08.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.