The Revolutionary War established the model, including tensions and flaws, for later conflicts.

By Dr. Charles A. Stevenson

Adjunct Lecturer in American Foreign Policy

Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS)

Johns Hopkins University

Introduction

[The Congress] think it but to say Presto begone, and everything is done.

George Washington, 17771

We don’t choose to trust you Generals, with too much Power, for too Long Time.

John Adams to General Horatio Gates2

George Washington was torn by the Continental Congress’ offer to lead the army assembled outside of Boston in June, 1775. Like other eighteenth century gentlemen, he welcomed the chance to demonstrate his military prowess and win fame and glory. But he knew the risks were great and his family and estate might suffer. As he wrote to his wife Martha on June 18, enclosing his hastily drafted will, “life is always uncertain, and common prudence dictates to every man the necessity of settling his temporal concerns while it is in his power ….” He also proclaimed, “I shall rely, therefore, confidently on that Providence which has heretofore preserved and been bountiful to me, not doubting but that I shall return safe to you in the fall.”3 In fact, Washington was to be on duty and away from home for the next seven years, except for 10 days just before the climactic battle at Yorktown in 1781. Besides enemy forces and the privations of eighteenth century military encampments, Washington also had to contend with the Continental Congress, a body ill-suited to manage a life-or-death conflict. The Congress was a part-time group of lawyers, merchants, and farmers gathered from the 13 colonies to fashion a common response to British policies in North America. It had no power to raise money or armies, but was dependent on the voluntary responses of the various provincial legislatures to its requests. Prior to independence, foreign recognition, and the election of new state governments under new constitutions, it had questionable legitimacy. Twice it was forced to flee its home base of Philadelphia to escape capture by the British. Yet it wrote the rules and gave the guidance to Washington and his Continental army, and struggled to acquire the weapons and supplies that allowed it to survive and fight and ultimately win. In that long process of war and diplomacy, fundraising and law-making, consideration of matters profound and mundane, the Continental Congress and Washington set precedents and practices which have endured into the twenty-fi rst century. The civil–military relations during the Revolutionary War established the model, including tensions and flaws, for later conflicts.

Decisions for War

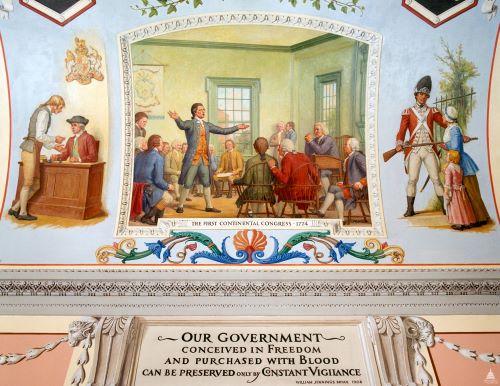

It was by no means inevitable in June 1775 that the 13 colonies would declare their independence or be successful in achieving it. The First Continental Congress, meeting in the fall of 1774, declared its fealty to King George III and blamed parliament for “unjust, cruel, and oppressive acts” against the people of Massachusetts. The delegates called for a boycott of British goods and passed Articles of Association to monitor its implementation through local committees of correspondence. They hoped that redress could be achieved peacefully. When sending copies of its resolutions to Benjamin Franklin in London, the Secretary of the Congress, Charles Thomson, wrote, “Even yet the wound may be healed & peace and love restored: But we are on the brink of a precipice.”4

By the time the Second Continental Congress assembled on May 10, 1775, however, blood had been shed at Lexington and Concord and an army of perhaps 18,000 New Englanders had gathered near Boston to fi ght the British force. The delegates authorized several preparations for war even as they named a committee to draw up a petition to the king for peace. On June 3, the congress set up a committee to consider ways and means of borrowing £6000 to buy gunpowder. On June 14 it called 10 companies of expert riflemen be raised in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia and sent to Boston. The same day it appointed a committee to “draft rules and regulations for the government of the army.” On June 15 it voted to name George Washington “to command all the Continental forces.” And on June 16 it adopted a plan of organization for the army and established a committee to prepare instructions.5 The next day, redcoats and patriots clashed in what came to be called the battle of Bunker Hill.

Washington was chosen because the New Englanders recognized the value of having a Virginian in charge of what were then mostly local soldiers. John Adams made the nomination, and the assembly agreed unanimously. Connecticut delegate Eliphaler Dyer wrote that it was “absolutely Necessary in point of prudence” to pick someone from outside New England because “it removes all jealousies, more firmly Cements the Southern to the Northern, and takes away the fear of the former lest an Enterprising eastern New England Genll. Proving successful, might with his Victorious Army give law to the Southern or Western Gentry.”6 Congress’ endorsement and Washington’s leadership made Boston’s fight America’s fight.

Dyer’s comment demonstrates that, even if fighting for their liberties, the colonial leaders were concerned about the threat from a standing army. They knew quite well what Oliver Cromwell had done barely a century earlier in Britain when he led his New Model Army first against the king and later against any who opposed his dictatorship. Samuel Adams warned,

Soldiers are apt to consider themselves as a Body distinct from the rest of the Citizens. They have their Arms always in their hands. Their Rules and their Discipline is severe. They soon become attached to their officers and disposed to yield implicit obedience to their Commands. Such a Power should be watched with a jealous Eye.7

Even the Virginia Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason, explicitly said, “that standing armies in time of peace should be avoided as dangerous to liberty; and that in all cases the military should be under strict subordination to, and governed by, the civil power.”8

While the Continental Congress sometimes gave near-dictatorial powers to Washington and other commanders for specific operations in particular regions, it remained on guard, and with tight purse strings, throughout the revolutionary struggle. And the Framers of the Constitution took special pains to guarantee civilian control in the new government by numerous provisions, including a reliance on a militia force rather than a standing army.

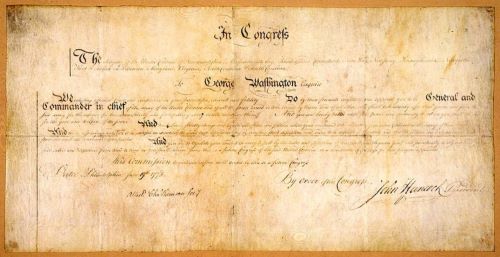

Washington‘s commission from the Congress told him “punctually to observe and follow such orders and directions, from time to time, as you shall receive from this, or a future Congress of these United Colonies, or committee of Congress.”9 His formal instructions listed as the first requirement to report back as soon as possible on the status of his own troops and their provisions. He was, however, given the power “to use your best circumspection and (advising with your council of war) to order and dispose of the said Army under command as may be most advantageous ….”10 In deference to this provision, or perhaps from an excess of caution, Washington felt compelled at least until 1777 to consult his senior subordinates and obtain majority approval from that a council of war before undertaking major operations.11

A persuasive explanation for why Washington accepted Congress’ nitpicking and micromanagement, and tolerated its frequent failures to provide adequate resources, comes from his definitive biographer, Douglas Southall Freeman:

In dealing with Congressmen and in winning their support, Washington’s experience as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses was of value beyond calculation. Nothing he possessed, save integrity, helped him so much, from his very first day of command, as his sure and intimate knowledge of the workings of the legislative mind. In the discharge of every duty to Congress and in the presentation of every request, his approach could be accurate, informed, and deferential. … Now that he had met and had conversed with some of the best men of every Colony, he was able to understand their problems and those of America.12

Congressional guidance reached a surprising level of detail in the general orders approved on June 30. These articles of war were a slightly revised version of the existing British provisions, running through 69 paragraphs. They included: a recommendation “diligently to attend Divine Service” – article II; a 4 shilling penalty for “profane cursing or swearing” – article III; demotion to private of any noncommissioned officer for neglect or waste of ammunition, arms, or provisions – article XV; immediate death penalty for anyone who “shamefully abandon[s] any post committed to his charge” – article XXV; a limitation on non-capital punishments to 39 lashes and fines of two months pay – article LI; a ban on selling liquor or entertainment “after nine at night …or upon Sundays, during divine service or sermon” – article LXIV.13 By the end of 1776, however, in response to military setbacks, Congress increased the number of permitted lashes to 100 and also increased the number of crimes for which the death penalty could be imposed.14

Not content to pass resolutions and appoint committees, more than half the delegates journeyed to Cambridge after their August 1 adjournment in order to see the fledgling army firsthand.15 They returned in September eager to continue the military buildup.

War Aims

Prior to the Declaration of Independence, the Continental army had a limited objective: “for the defence of American liberty and for repelling every hostile invasion thereof,” in the words of Congress’ instructions to Washington. In passing the articles of war on June 30, Congress acknowledged that British reinforcements were headed toward Boston and declared that an American force “be raised sufficient to defeat such hostile designs, and preserve and defend the lives, liberties and immunities of the Colonists.”16

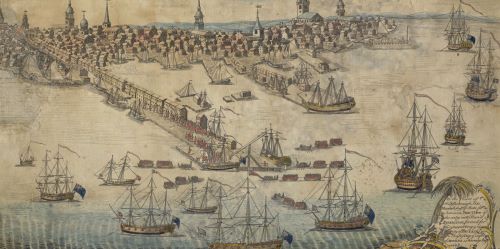

In practice, these words meant removal of the British troops from Boston, repeal of the other sanctions imposed on Massachusetts, and a restoration of pre-1774 colonial liberties. Although Congress urged a direct attack on General Gage’s troops in Boston, even offering a bonus of a month’s pay in case of success, Washington instead maneuvered. In a nighttime surprise, his troops seized Dorchester Heights, thus allowing them to threaten British land and naval forces. The Redcoats’ withdrawal on March 17, 1776 was part of a strategic decision by the new British commanding general to relocate his expanding forces to New York and try to sever the New England colonies from their brethren to the south.

By that time, sentiment throughout the colonies was turning in favor of independence. George III had proclaimed the colonies in a state of rebellion in August 1775 and ordered that “all our Officers, civil and military, are obliged to exert their utmost endeavours to suppress such rebellion, and to bring the traitors to justice.”17 Local assemblies began petitioning the Congress to declare independence, but many delegates, especially from the middle colonies, felt that the time was not yet ripe and held out hope that British peace commissioners might arrive with conciliatory proposals.

Although British troops had been withdrawn from Boston, the Crown was assembling a huge force of British and German troops, more than 32,000, to send against the rebels. Anticipating an attack, even the moderates supported measures to prepare for war. In the spring of 1776, Congress approved funds for presents and bribes for Indian leaders, to try to keep them neutral, and summoned Washington to Philadelphia for consultations at the end of May. Those conferences led to decisions to send 6,000 reinforcements to Canada, to raise a force of 13,000 for New York, and to establish what was called a 10,000-man “flying camp” of militia that could be deployed where needed.18 A few months before, Congress had authorized privateering against British ships and building four armed ships for a new American navy.

On June 7, Richard Henry Lee offered the radicals’ three-fold plan for dealing with the British threat. The first provision was the famous declaration “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States ….” But the second and third provisions were equally significant. They called for “the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances” and for “a plan of confederation.”19 The rebels recognized that independence required support from abroad and greater unity at home.

Throughout the long conflict, the congressional leaders never wavered from their insistence on full independence. Even when their major cities were captured by the British, when the army was nearly destitute at Valley Forge, when the currency collapsed, when soldiers turned mutinous over inadequate pay – the patriots held firm.

And they suffered for it. By the time the war ended, more than half the members of the Continental Congress had seen their property looted or destroyed. Many were imprisoned or driven into hiding. Of the 342 men elected at one time or another to the Congress, 134 served in the militia or the Continental army – and of them, one was killed in action, 12 were seriously wounded, and 23 were taken prisoner.20 In these and other ways, they paid a price for their patriotism. Their pledge of their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor was not mere rhetoric.

Strategy

From Congress’ standpoint, the way to achieve independence was to persuade others of the justness of the American cause, to enlist foreign support, to raise a large local force to fight the British when they approached, and to capture Canada so that the British had no foothold in North America.

In support of this strategy, Congress took numerous actions in the month after voting to create a Continental army in June 1775. It approved a formal “Address to the Inhabitants of Great Britain” complaining that “our Petitions are treated with Indignity; our Prayers answered by insults.” It also sent letters to the people of Ireland and Jamaica and the “oppressed inhabitants” of Canada, expressing the hope “of your uniting with us in the defense of our common liberty.”21

On July 6, 1775, Congress issued a declaration “setting forth the causes and necessity of their taking up arms.” This document, a blend of drafts from moderate John Dickinson of Pennsylvania and the radical Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, summarized the history of “These devoted colonies” and their “peaceful and respectful behaviour” until the British government decided to change the established form of government and impose a new despotism. The declaration charged that British troops “have butchered our countrymen” and “spread destruction and devastation.” It asserted that “Honour, justice, and humanity, forbid us tamely to surrender that freedom which we have received from our gallant ancestors.” Yet it stopped short of independence. “We have not raised armies with ambitious designs of separating from Great-Britain, and establishing independent states.” Instead, it pleaded for “reconciliation on reasonable terms.”22

In addition to these rhetorical appeals, Congress took several concrete actions in the same period. On June 22, the delegates approved the issuance of $2 million in bills of credit to pay for the army. On June 27 it ordered preparations for talks with Indian tribes, to assure their neutrality in the conflict. The same day, it directed Major General Schuyler to seize St. Johns, Montreal, and any other parts of Canada “which may have a tendency to promote the peace and security of these Colonies.” And on July 15, it voted an exemption from the boycott law for trade in gunpowder, saltpeter, sulphur, cannon, muskets and other munitions. On July 18 it recommended that each colony take steps to defend its harbors and seacoasts. And on July 21 it received for later consideration Benjamin Franklin’s proposal for Articles of Confederation.23 In December, Silas Deane of Connecticut would be sent to France to seek moral and material support.

These measures demonstrate Congress’ approach prior to the Declaration of Independence – public appeals, military mobilization, search for allies, and political cooperation. The intended role of the army was to drive Gage from Boston and to capture Canada.

Washington saw the strategic problem differently. He thought that not to lose was to win, that the British would ultimately tire of a protracted conflict. He was at first dubious of obtaining sufficient foreign support and, as an infantryman, failed to appreciate the impact of the French navy in diverting and defeating the Royal Navy. He opposed excessive reliance on the militia, rather than the Continental army, because he repeatedly witnessed its shortcomings – poor training and command, brief enlistments, and a tendency to retreat from battle. “Are these the men with whom I am to defend America?” he cried at the battle of Kip’s Bay in New York. Earlier, he had described the forces assembled at Cambridge as he took command as “an exceedingly dirty and nasty people.” He was indifferent to the congressionally mandated invasion of Canada, which ultimately failed.24

The commander-in-chief adopted a defensive strategy, hoping to avoid a decisive battle which could result in a decisive defeat. As Russell Weigley wrote, “the strategy of the American armies in the Revolutionary War had to be a strategy founded upon weakness.”25 Washington said he could not divide his army without risking great losses. And he opposed making major attacks “since the Idea of forcing their lines or bringing on a General Engagement on their own Grounds, is Universally held incompatible with our Interest.”26 As a result, Washington avoided confrontation with main British army units whenever possible.27

Congress was ill-equipped to manage the war but felt responsible for its conduct. A legislative body, by its nature, cannot easily make timely decisions or regulate the implementation of its orders. It is better at retrospective oversight than day-to-day management. Yet there was no other entity to run the war effort. There was no other government that involved all of the colonies.

Starting in 1776, Congress felt obliged to be in session almost continuously until 1784, recessing only for a few days at a time. That reduced attendance, as members went home from time to time to take care of personal business, but it preserved some sort of government in being throughout the war. The demands were even heavier on those appointed to serve on committees, which dealt with particular issues. At first, the assembly created new committees for each subject and proposal, from drafting documents to handling relations with Indian tribes. By the end of 1775 it created standing committees to replace the ad hoc ones. A Secret Committee was set up to import munitions and other necessary supplies. It later became the Commerce Committee. A Committee of Secret Correspondence maintained communications with American agents and informants abroad. It later became the Committee on Foreign Affairs. One of the most important panels was the Board of War and Ordnance, which was concerned with supplying the army. It acted as the executive over the army until 1777, when Congress created a subordinate Board of War, consisting of full-time offi cials who were not delegates to the Congress. Only in 1781 did it create executive departments – for foreign affairs, war, and the navy.28

There was a voluminous correspondence between the Congress and the commander-in-chief. The general requested supplies and guidance and received a healthy dose of the latter. In addition, there were six special commissions sent to Washington’s headquarters, at least one each year, mainly to investigate problems and report back to the Congress. As John Adams wrote, “This is the Way to have things go right: for Offi cers to correspond constantly with Congress and communicate their Sentiments freely.”29

Washington sometimes resisted, as in this letter of March 14, 1777. “Could I accomplish the important objects so eagerly sought by Congress – ‘confining the enemy within their present quarters, preventing their getting supplies from the country, and totally subduing them before they are reinforced’ – I should be happy indeed, But what prospect or hope can there be of my effecting so desirable a work at this time? The enclosed return, to which I solicit the most respectful attention of Congress, comprehends the whole force I have in Jersey.”30

In practice, Congress meddled more with the armies in the north and south than in the middle states, where Washington was usually headquartered. Although he was the overall commander, he acceded to those forces’ greater autonomy from him and greater oversight by Congress in those regions.31 War by committee proved unsatisfactory, leading to the creation of executive agents under the committees and eventual regular departments to manage particular activities. These experiences persuaded the revolutionary leaders, when they met to craft a new Constitution, to create institutions that vested power and authority in a strong executive – and in a strong central government. But those lessons came only after painful experiences.

Personnel

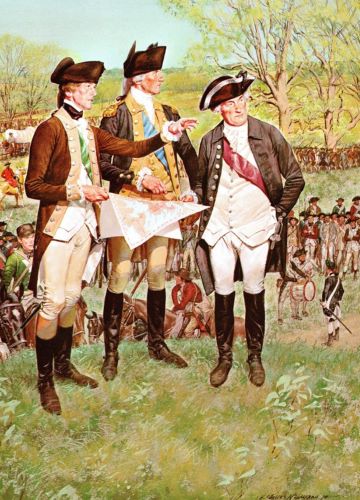

Just as Washington had been selected for geographical as well as military reasons, Congress named other general officers for the same reasons. Major general commissions went to Artemus Ward, head of the Massachusetts militia; two former British officers now Virginians, Charles Lee and Horatio Gates; and Israel Putnam of Connecticut and Philip Schuyler of New York. Brigadier commissions went mainly to New Englanders, since theirs was the only real force in being at the time. Regimental officers were supposed to be recommended by provincial assemblies, subject to Washington’s approval.32

After two years of pleas and demands from would-be generals and their congressional patrons, Congress finally in February 1777 adopted what was called its Baltimore resolution on the subject: “In voting for general officers, a due regard shall be had to the line of succession, the merit of the persons proposed, and the quota of the troops raised, and to be raised, by each state.”33 In practice, both Washington and the Congress worked through the local governors in picking local commanders.34

As the war went on, Congress came under pressure to give high ranks to foreign officers recruited in Europe by Silas Deane. Some, like Steuben and Lafayette, proved enormously able. Others had inflated credentials and insufficient skill. American officers also used their political contacts to try to advance their promotions and careers – a pattern also followed in later decades. Congress insisted, during the revolution and as part of the Constitution, on having ultimate power over the selection of military officers.

Junior officers and enlisted personnel were recruited locally, though Congress requested particular force levels during the course of the war. Those in the militia typically served only a few months each year, and even the Continental army had trouble obtaining people for more than a year at a time. One reason for Washington’s dramatic 1776 Christmastime attack across the Delaware against the German troops encamped at Trenton was to make use of his men before they returned home as their enlistments expired at the end of the year. He also desperately needed a morale-boosting victory after his defeats earlier that year around New York and while retreating across New Jersey.35 Congress tried to boost enlistments with various bonuses and pension promises, but these proved less successful as the currency lost value.

During the course of the war, the Congress named 73 general officers. Fifty-two had previous military experience – 16 in an English or European army, and 36 in the colonial militia. Even some with no prior experience performed amazingly well, including Henry Knox, who organized the American artillery units, and Nathanael Greene, who learned so well and so quickly that he often commanded in Washington’s absence and later organized an innovative guerrilla campaign in the south.36 On the other hand, seven of the 29 major generals resigned, one died, one was discharged, and one committed treason.37

The Continental army never had more than about 17,000 under arms at one time, although over the course of the war as many as 232,000 men were formally enlisted. Perhaps one-fourth of the continental soldiers took unauthorized leave at some time. Militia forces were much larger throughout the war, but they served under short, irregular enlistments and were less well trained. The largest force in any one year, regular and militia, was estimated to be 47,000 men in 1776. Britain nearly doubled the size of its pre-war army, including hiring 30,000 German mercenaries – uniformly labeled Hessians, though they came from many Germany states. In 1776, it sent 50,000 troops to garrison Canada and fight the rebellious colonies. The armies directly confronting Washington ranged from 28,000 to 34,000 soldiers.38

The Continental navy was a much smaller force, and it faced the large and powerful Royal Navy. While some delegates such as John Adams saw the value of a fleet, other shrank from the high shipbuilding costs. Congress named a navy committee in October 1775. A few months later it purchased eight ships and ordered the building of 13 new frigates. In addition they sought to draw upon state naval forces, which never amounted to more than 40 boats overall. Consequently, the bulk of the commerce-raiding done by American ships was done by privateers. More than 2,000 got letters of marque authorizing them to attack and seize British ships. Interdiction by American and European ships was substantial – over half the 6,000 British ships involved in overseas trade fell into enemy hands at some point in the war.39

American shipbuilding, however, was far less successful. Only six American-built frigates ever got to sea, and only one survived the war. Only one larger ship-of-the-line was finished before the end of the war. In July 1777 Congress was so upset at the escalating costs of ships being built it gave permission to its committee to “put a stop” to construction because of the “extravagant prices now demanded for all kinds of materials used in ship-building, and the enormous wages required by tradesmen and laborers.” Despite the cost problems, the committee felt the need was too great, so it approved continued payments.40

Supply

Congress also had the clear responsibility of obtaining the supplies for the army it had created and paying its people. These proved to be enormous challenges, poorly met. Three weeks before declaring independence, after repeated requests from Washington for the delegates to set up some system of management, Congress created a five-member Board of War and Ordnance under John Adams as chairman. It was to keep records of all personnel and equipment and was responsible for “the raising, fitting out, and dispatching all such land forces as may be ordered for the service of the United Colonies.”41 Later, in July 1777, a subordinate Board of War was created, with three full-time officials, not members of Congress. Only in 1781 did Congress create a regular war department.

The Board had an impossible set of tasks. There was little domestic production capability for key items – no gunpowder, saltpeter, iron and steel, or canvas for ship sails. Special committees were established to search, inquire, beg, and contract for needed items. The army in the field was often successful in capturing British supplies of needed items or in seizing them locally, often from British loyalists. Privateers also captured significant supplies at sea and turned them over to the army. Congress also let contracts to American suppliers for food and clothing and some other supplies, using early forms of advertising, bids, and proposals. When this system broke down in 1780, mainly because of the depreciation of the Continental currency used to pay for purchases, Congress turned the supply problem over to the individual states for the duration of the war.42

Even when supplies were available, logistical problems sometimes prevented goods from reaching the army. It has been estimated, for example, that there was enough food in the area to feed the forces starving at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777, but that there were not enough wagons available to transport it to Washington’s camp.43

The contracting system showed many of the problems and dysfunctions that have plagued US military procurement over the centuries. Paperwork was burdensome; suppliers cheated; when complaints arose, Congress investigated. Nevertheless, a mere handful of overworked officials developed a system of contracting and delivery that equipped and fed a victorious army.

Congress tended to control even the smallest projects with its approval required for each payment. While it set specifications for army items, it used on-site supervision of shipbuilding. As Lucille Horgan notes, “No matter which organization or government official was given contracting authority, Congress usually reserved the right to approve or disapprove the terms of individual contracts, and especially of final approval for payment.”44

Individual soldiers were usually required to supply their own firearms, blankets and knapsacks. Sometimes unit commanders were given authorization to provision themselves by foraging locally.45

To pay the troops and to buy their supplies, Congress had no money. There was no indigenous national currency, so Congress printed what it needed and asked the colonies to pay proportionate shares of their own taxes. Within five years Congress had circulated $200 million of these bills of credit, and few Americans would willingly accept them as payment for anything. “Not worth a Continental” became the slogan. As part of its measures in 1780 to put the government on a sounder footing, Congress devalued the currency, 40–1, so that the nominal debt shrank to only $5 million.

Meanwhile, officers were demanding the British system of half-pay for life for veterans. Despite repeated requests from Washington, Congress resisted this pension plan until October 1780, though it did vote death benefits for officer and enlisted families and half pay for life for those disabled in wartime.46 Eventually it created a more generous pension system.

Tactics

As might be expected of a legislative body trying to manage a war, Congress swung between intrusiveness and desperate delegation, seeking but rarely finding an agreeable balance between civilian and military responsibilities. Fortunately for American democracy, George Washington accepted Congress’ authority and deferred to its practices, despite frequent frustrations.

His first clear mission was to drive the British from Boston, which he accomplished in March 1776. The congressionally inspired invasion of Canada was conducted by other forces. While they succeeded in capturing Montreal, they were forced to retreat from Quebec in the spring of 1776. Washington recognized that the British were likely to attack New York, so he positioned his expanded army there, only to be defeated in a series of dispiriting engagements in the summer and fall of 1776.

Less than six months after confidently declaring independence, the frightened Congress fled to Baltimore on December 12. Two weeks later lawmakers voted to vest Washington “with full, ample and complete powers to raise and collect together, in the most speedy and effectual manner, from any or all of these United States, 16 battalions of infantry, in addition to those already voted by Congress” as well as “to arrest and confine persons who refuse to take the continental currency, or are otherwise disaffected to the American cause.”47

So guilty did the delegates feel about their abdication of civilian control that three days later they issued a circular letter to the 13 states explaining “Congress would not have Consented to the Vesting of such Powers in the Military Department … if the Scituation of Public Affairs did not require at this Crisis a Decision and Vigour, which Distance and Numbers Deny to Assemblies far Remov’d from each other, and from the immediate Seat of War.”48 Once the crisis passed with Washington’s victories at Trenton and Princeton, John Adams counseled against letting Washington retain too much power. As he told the delegates, “It becomes us to attend early to the restraining our army.”49

Congress adopted the same desperation measures in June 1780, after the surrender of a large American force at Charleston, South Carolina, when it gave General Gates command of the southern army and empowered him “to take such other measures, from time to time, for the defence of the southern states as he shall think most proper.”50

Congress returned to Philadelphia in March 1777, but had to flee in September when General William Howe occupied the city. The delegates relocated first to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and then to York, where they stayed until Howe’s evacuation in June 1778. Washington fought the British inconclusively at Germantown and Brandywine and then established winter quarters at Valley Forge.

The most important battle of 1777, and perhaps of the war, was fought at Saratoga, in New York, where British General John Burgoyne was defeated by forces led by General Horatio Gates. Thereafter, British infantry action was confined to the southern states – and the French government decided that the rebels had enough chance of success that they deserved their aid and support.

Congress had been seeking foreign alliances from the start of the conflict. It sent Silas Deane to France in 1775, following with Benjamin Franklin and John Adams in 1776. These and other American emissaries courted public opinion, negotiated treaties, and procured supplies. What had been a localized British–American conflict became a European war, with the Royal Navy threatened by the French fleet in Europe and the Caribbean and Gibraltar threatened by Spain.

When the British sent a peace delegation in 1778, the Congress spurned it, demanding recognition of American independence as a precondition to any talks. Despite the many positive developments, the war dragged on through inconclusive engagements in 1779 and into a major crisis in 1780. That year the British took control of the three most southern states, defeating American forces at Charleston and Camden, South Carolina. Congress devalued the currency and confronted angry debt holders and soldiers, including a mutinous Pennsylvania army that threatened to besiege the Congress in January 1781.

Fortunately the French responded with its fleet, some soldiers, and six million livres for the Continental army. Congress also moved to make the government more streamlined, professional, and efficient by creating executive departments for foreign affairs, finance, war and the navy. And on March 1, the Articles of Confederation went into effect, following a three-year delay as Maryland insisted that other states drop their claims to western lands, thus leaving them open for settlement as new states and territories.

The new government was still so weak and poor, however, that when the express rider arrived in Philadelphia on October 22 with word of the British defeat at Yorktown, there was not enough hard money in the treasury to pay him, so members of Congress each had to contribute a dollar of their own.51

War Termination

Even then, the war was not really over, for British troops continued to occupy Charleston and still held New York, as they had since 1776. But the key American objective had been achieved: independence was not at issue in the peace talks.

Congress wanted to reduce the army in 1782, pending the conclusion of a formal peace treaty, but Washington and other officers resisted. It finally adopted a plan of voluntary retirement for officers, beginning in 1783.

Meanwhile, the most serious civil–military clash of the entire war occurred among Washington’s troops at Newburgh, New York in March 1783. Although peace commissioners had been meeting during 1782, British envoys waited until October to indicate a willingness to grant independence. Preliminary articles of peace were signed in January 1783 and the formal British announcement of a cessation of hostilities was announced only on February 20. Meanwhile, the continental army was being cut back, but without the promises of substantial pensions desired by the soldiers. The army could not be disbanded because British troops still controlled, among other positions, New York – as they would until November 1783.

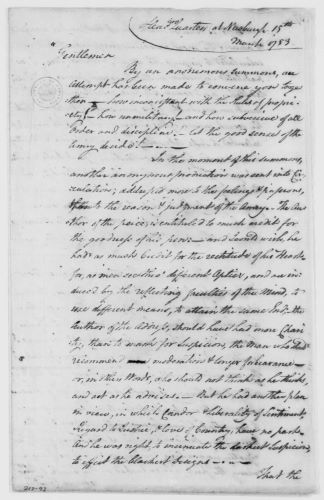

A junior officer circulated a paper among the disgruntled officers which threatened Congress with disobedience unless officers gained greater respect and remuneration from the legislature. The document also criticized Washington for siding with the lawmakers. A few weeks earlier, a group had petitioned Congress claiming: “We have borne all that men can bear – our property is expended – our private resources are at an end.” These soldiers asked that their half-pay pensions be commuted to five years of full pay. Otherwise, they warned, “any further experiments on their patience may have fatal effects.”52 The latest circular threatened not to disband or not to fight unless their grievances were resolved. Washington responded by calling a general meeting. Addressing the officers, the general at first argued against the substance of the paper. Then he pulled out his spectacles to read a letter from a congressman explaining the financial problems. Few had seen him with glasses before. He explained, “I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind.” His gesture, the humanity of his appeal, turned the tide of sentiment, and some officers openly wept. The Newburgh Conspiracy evaporated.53 The day Congress learned of these events, it voted full pay for five years for officers and full pay for four months for enlisted men. It left unresolved whether the payment would be in cash or securities with 6 percent interest. But the crisis had passed.54

Washington saved the day at Newburgh, as he had protected and deferred to the authority of Congress during the war. But the incident reminded the American politicians that they had to be wary in their dealings with the warriors. Those final months witnessed the disintegration of the Continental army as its members returned to civilian life. By the summer of 1784, by order of Congress, the army was cut to 80 men, left to guard military stores at West Point and Fort Pitt.55

In diplomatic and economic terms, the peace settlement was a victory for the new nation. Having lost the colonies, the British were eager to regain a profitable trading partner. Having been defeated in their attempts to conquer Canada, the newly united states now had uninhibited access to lands west of the mountains.

Lessons of the War

The Revolutionary War demonstrated that a disorganized group of colonials could come together and prevail against the greatest military power of the day. Their appeal was conservative in requesting rights that were fundamental to Englishmen and radical in calling for government by the consent of the governed. In a few months, these colonials went from letters and newspapers circulated by committees of correspondence to a representative congress making decisions and issuing orders that were actually obeyed. They fought a war without a real government, without the power of taxation that enables governments to raise funds for armies and navies, and without a bureaucracy or officer corps to fight for the independence their congress declared.

If one miracle was that such a hodgepodge succeeded, a second miracle was that its chosen military leader was a man of such integrity and devotion to political principle that he accepted and endured the frustrations and indignities of legislative control. As Richard Kohn argues, “George Washington never succumbed to temptation.” He never used his authority or celebrity to challenge the Congress and the inefficient process it had created. Before, during, and after Newburgh he rejected calls for military insubordination. But as one observer noted in his journal, “The officers look upon Congress with an evil eye, as men who are jealous of the army, who mean them no good, but mean to divide and distress them. It is surprising with how much freedom & acrimony they declare their sentiments.”56

Washington bridged the civil–military gap and set the mode of restraint and deference for future generations. Congress, too, in its own way, set the precedents for future conduct in wartime: hard work, close oversight, inadequate material support, and political responsiveness to public opinion.

More immediately, the war taught lessons for the new American leaders who were trying to make their independent government succeed. It reinforced their view that the government needed – for national security reasons at least – to be strong enough to tax in order to raise armies and navies, to be cohesive enough to make foreign treaties and alliances. It convinced them that they could create and sustain a Lockean government of separated institutions sharing powers while still being strong enough to preserve their national integrity. The war set the stage for peace; the Continental Congress set the model for the new government; and George Washington played the key role as a deferential commander-in-chief.

Endnotes

- Quoted in E. Wayne Carp, To Starve the Army at Pleasure, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1984, p. 181.

- Lynn Montcross, The Reluctant Rebels: The Story of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1950, p. 147.

- Quoted in Douglas Southall Freeman, George Washington, Volume Three: Planter and Patriot, New York, NY: Scribner’s, 1951, p. 453.

- Montcross, pp. 50 and 57.

- Montcross, pp. 70–1; Russell F. Weigley, History of the United States Army, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984, pp. 28 and 31.

- Quoted in Don Higginbotham, The War of American Independence, New York, NY: Macmillan, 1971, pp. 84–5.

- James Kirby Martin and Mark Edward Lender, A Respectable Army: The Military Origins of the Republic, 1763–1789, Arlington Heights, IL: Harlans Davidson, 1982, p. 75.

- Quoted in Higginbotham, Wa r, p. 206.

- Journals of the Continental Congress, volume 2, June 17, 1775, p. 96.

- Journals, volume 2, June 20, 1775, pp. 100–1.

- Higginbotham, Wa r, p. 211.

- Feeman, volume 3, p. 446.

- Journals, volume 2, June 30, 1775, pp. 111–22.

- Martin and Lender, p. 76.

- Montcross, p. 89.

- Journals, volume 2, pp. 100 and 112.

- Proclamation of Rebellion, August 23, 1775, at http://www.britannia.com/history/docs/procreb.html.

- Montcross, pp. 140–2.

- Montcross, p. 144.

- Montcross, pp. 131 and 191.

- Montcross, p. 82.

- See text at Yale Law School’s Avalon Project: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/arms.htm.

- Montcross, pp. 77, 79, 83 and 85.

- Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1973, pp. 5, 10 and 11; Montcross, p. 94.

- Weigley, Way of War, p. 5.

- Quoted in Weigley, Way of War, p. 4.

- Weigley, Way of War, p. 13.

- Jack N. Rakove, The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, pp. 195 and 199.

- Quoted in Carp, p. 37; Louis Clinton Hatch, The Administration of the American Revolutionary Army, New York, NY: Burt Franklin, 1904, p. 20.

- Montcross, p. 205.

- Higginbotham, War, p. 92.

- Montcross, p. 72.

- Quoted in Martin and Lender, p. 43.

- Mark V. Kwasny, Washington’s Partisan War, 1775–1783, Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1996, pp. 58 and 136.

- Washington had to rely on regulars for the attack; no militia were willing to join the operation. Kwasny, p. 136.

- T. Harry Williams, The History of American Wars From 1745 to 1918, New York, NY: Knopf, 1981, p. 46.

- Don Higginbotham, War and Society in Revolutionary America, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1988, p. 91.

- Williams, pp. 44–5; Larry H. Addington, The Patterns of War since the Eighteenth Century, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, Second Edition, 1994, p. 12; Higginbotham, War and Society, p. 99.

- Martin and Lender, p. 143.

- Lucille E. Horgan, Forged in War: The Continental Congress and the Origin of Military Supply and Acquisition Policy, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002, p. 109; Addington, p. 14.

- Quoted in Weigley, Army, p. 46.

- This story is told in impressive detail in Horgan. See ch. 1, pp. 1–22.

- R. Arthur Bowler, “Logistics and Operations in the American Revolution”, in Don Higginbotham (ed.), Reconsiderations on the Revolutionary War, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978, p. 59.

- Horgan, p. 101.

- Horgan, pp. 11 and 13.

- Montcross, p. 266.

- Montcross, p. 194.

- Montcross, p. 194.

- Montcross, p. 227.

- Montcross, p. 301.

- Montcross, p. 323.

- Martin and Lender, p. 187.

- Martin and Lender, pp. 191–3; Montcross, pp. 349–50.

- Weigley, Army, p. 77.

- Weigley, Army, p. 81.

- Richard H. Kohn, “American Generals of the Revolution: Subordination and Restraint”, in Don Higginbotham (ed.), Reconsiderations on the Revolutionary War, Westport, CT: 1978, pp. 117 and 109.

Chapter 2 (15-29) from Warriors and Politicians: US Civil-Military Relations under Stress, by Charles A. Stevenson (Routledge, 07.13.2006), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.