The colony underwent a transformation remarkably similar to the state-building process of the great European powers.

By Dr. William Pencak

Professor Emeritus of History

Penn State

‘Join or Die.’1 So Benjamin Franklin warned his fellow American colonists shortly after the French and Indian War began in 1754. Beneath a diagram of a snake severed in thirteen pieces depicting the fragmented provinces of British North America, he lamented ‘the extreme difficulty of bringing so many different governments and assemblies to agree in any speedy and effectual measures for our common defense and security, while our enemies have the very great advantage of being under one direction, with one council and one purse’.2 Franklin’s argument applied not only to the need for combination at this juncture among the mainland provinces. It articulated the particular case of a general truth: states hampered by internal bickering fail to mobilise their military resources effectively and rapidly find theIr domestic weaknesses compounded by impotence in foreign affairs.

Franklin need only have turned to eighteenth-century Europe for proof of his statement. Successful states developed efficient means of collecting taxes, conscripting soldiers, and neutralising resistance to political centralisation. Only such techniques could forge the principal tool of national survival – a competitive military establishment. The sorry decline of Poland, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire from their seventeenth-century glory can be attributed to the monarch’s inability to check the autonomy of the nobility. On the other hand, Prussia and England overcame the handicap of relatively small populations by developing brutal but effective means of recruiting respectively the most powerful army and navy in Europe, and succeeded in integrating the landowning class into civil and military administration. France, Austria, and Russia represented the intermediate case of large nations which eliminated local privileges and opposition intermittently and imperfectly, but maintained major power status through sheer size and periodically strong rulers. Nations able to neutralise the institution eighteenth-century Americans associated with liberty-the legislative assembly-survived and increased in strength; states too tender of the corporate privileges of their subjects deteriorated or expired.3

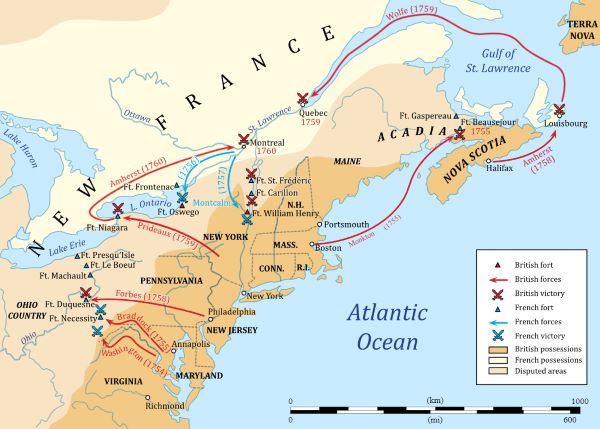

Yet the American colonies neither joined nor died during the great mid-century wars which finally eliminated the French menace. True, every mainland province furnished troops and supplies for the common cause, However. this voluntary cooperation proved so ineffectual that in addition to provincial levies, Britain had to furnish regular regiments greater in number than the French-Canadian forces in order to bring the war to an end. Even after Wolfe defeated Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham, British troops had to be summoned to deal with pockets of Indian resistance in Pennsylvania and South Carolina. Throughout the French and Indian War, British officers and administrators complained of soldiers who deserted or refused to fight outside their home colonies, merchants who traded with the enemy, and assemblies which incomprehensibly did not vote adequate supplies and quarters for the very troops which guaranteed their existence. Such resistance to a more centralised administration, understandable in terms of the eighteenth-century Whig ideology by which the colonists measured their freedom, appeared suicidal in the context of modern world history which has required nations to stand united or fall divided. Only the knowledge that eighty thousand French Canadians could never destroy them, coupled with the fact of assistance from the mother country, permitted the Americans the luxury of adhering to liberties rendered obsolete by the realities of European international politics.4

However, even if the North American colonies were united only minimally among themselves, it can be demonstrated convincingly that at least one province underwent, with respect to its internal government and administration, a transformation remarkably similar to the state-building process of the great European powers. Between the outbreak of King George’s War inl 740 and the signing of the Peace of Paris in 1763, the Massachusetts General Court roused itself from a quarter-century of lethargy and achieved feats of taxation and mobilisation which Frederick the Great might have envied. Under the tutelage of William Shirley, governor from 1741 to 1756, the Bay Colony changed from one of the most truculent provinces in the empire to the most cooperative. However, the province’s mobilisation contained the seeds of its organisers’ destruction: the suffering engendered convinced the people that both imperial and local leaders posed serious threats to their liberties and well-being.

To effect this about-face, the very nature of Massachusetts’ political system had to change. A legislature primarily concerned with obstructing Britain’s plans to strengthen royal authority and with resolving disputes presented by towns and individuals became an active body which designed and implemented vast military campaigns. A potent faction devoted to the royal prerogative developed virtually ex nihilo supplanting the influence of the previously dominant country faction which had convinced the assembly that any increase in the governor’s power destroyed popular liberty. New systems of finance and public administration, and a new sense of mission emerged. For a quarter century, Massachusetts waged total war.

Massachusetts’ pre-eminence among the American colonies in fighting King George’s (1740-1748) and the French and Indian (1754-63) wars is indisputable. In the latter conflict, the Bay Colony outspent Virginia, the second most zealous province, £818,000 sterling to £385,000 collectively, or £20 to £14 per adult male. Annual levies from 1755 to 1759 numbered approximately 7000 soldiers; 5000 men were mustered in 1760 and 3000 per year until 1763. Such an army for a province with approximately 50,000 adult males meant that war was being waged on a scale comparable to the great wars of modern times.5 And in King George’s War, Massachusetts had the field almost to itself. Aside from grudging and minimal support from New York, the other New England colonies, and even Britain, the expedition which conquered Louisbourg in 1745 and the abortive Canada and Crown Point campaign of the following year were projected, manned, and supplied almost entirely by the Bay Colony.6

During King William’s and Queen Anne’s Wars, in 1690, 1706, 1709, and 1711, Massachusetts had prepared massive but unsuccessful expeditions to eliminate French power in Canada. Following the Peace of Utrecht in 1713, however, Massachusetts’ government lost much of its energy. The province devoted itself to settling the recently won frontier, trying to solve the perplexing problem of a rapidly depreciating currency, and foiling the efforts of royal governors to increase their power at the expense of the lower house. Localism, ideological wrangling, stalemate, and stagnation best describe the politics of the interwar period. At this time ‘the legislative agenda,’ as Michael Zuckerman has noted, ‘was substantially set by petitions from the towns and their inhabitants’.7 The General Court functioned, as its name implies, primarily as a court, settling disputes that became too hot to handle on the town level, determining the ownership of frontier lands, granting licenses to sell liquor, and voting an annual budget of approximately £10,000 sterling. Most of the money went to pay the salaries of the legislators, judges, and the handful of soldiers who garrisoned Boston’s Castle William and a few outposts in Maine. During the legislative session of 1743-1744, for instance, the last year before the Louisbourg campaign, 307 resolves passed. General provincial business accounted for only 98, and most of these consisted of routine matters such as voting salaries for all provincial officials from the governor to the door-keeper, approving the accounts of the county treasurers, and passing on bills to entertain various dignitaries. Over two-thirds of the business consisted of adjudicating items of interest to particular towns and individuals.8

In addition to settling local problems, the three branches of the Court devoted much of their energy to defining the limits of their respective powers. Beginning in 1720, Governor Samuel Shute (1716-1723) insisted that he had a right to veto the assembly’s choice of its speaker, especially when it selected the obnoxious Elisha Cooke, who had repeatedly referred to Shute as a ‘great blockhead’ and once accosted him, while intoxicated and semi-dressed, late at night on a Boston street. The matter was only resolved in 1726 when the Privy Council forced the deputies to accept an Explanatory Charter which decided the case in Shute’s favour.9

A similar dispute occurred when the home government saddled Shute’s successor, Lieutenant-Governor William Dummer (1723-1728), with an instruction requiring the annual redemption of Massachusetts’ paper currency-which derived its value by being redeemable for taxes in specified years-to forestall the inflation which had begun to affect British creditors. The house responded by refusing to vote any appropriations at all in 1727 until Dummer caved in and violated his orders. Massachusetts managed to circumvent instructions reducing its money supply until 1741, when parliamentary intransigence led to the abortive Land and Silver Bank schemes which nearly tore the province apart.10

The remaining two governors during the interwar years fared no better. William Burnet (1728-1729) spent his entire year and three months in Massachusetts insisting that the assembly should permanently guarantee the executive a salary of at least £1000 sterling per year. Such an act would prevent the governor from pleasing his constituents at the expense of his superiors. This controversy dragged on until 1735. Burnet’s successor Jonathan Belcher (1730-1741) finally worked out a compromise whereby the governor obtained an annually voted grant, but the house in turn promised that it would equal £1000 sterling and be voted at the beginning of each year’s session, instead of at the end after the governor had approved all of the assembly’s votes.11 The last of these jurisdictional disputes occurred when Belcher had to persuade the house that all money appropriated for the treasury by the deputies be spent merely with the approval of the governor and council for each specific disbursement. The lower house refused to yield this right from 1730 to 1733, and responded to Belcher’s demands by voting no money at all for nearly two years. As in the case of the Explanatory Charter, a sharp warning from the crown changed the deputies’ minds.12

The nature of political conflict in peacetime Massachusetts must be defined if the changes produced by war are to be fully appreciated. As noted, the principal controversy centred on the division of powers within the General Court. When not handling local business, the assembly spent its time arguing with the governor and council. House Journals for the 1720s and 30s contain hundreds of pages of messages in which both sides based their arguments primarily on the province charter and English precedents, with the assembly claiming the powers of the House of Commons, derived from the charter clause guaranteeing all the rights of Englishmen. The ‘Old Whig’ appeal to the natural rights of man and the ‘New Whig’ attack on executive corruption were conspicuous by their absence. Ideological debate, while intense, utilised a common language and did not delve deeply into the relationship of society and government. Both sides confined themselves largely to technical points of law.

The composition of factions between Queen Anne’s and King George’s wars also contrasted markedly with future patterns. No effective prerogative party existed in the legislature, since on every disputed point the interests of Massachusetts and Britain clashed rather than coincided. For example, many of the house’s denials of the governor’s power over the speaker passed unanimously. The most favourable vote Burnet ever obtained on the permanent salary was a 54 to 18 rejection. Even this vote occurred on a watered-down proposition which guaranteed payment only for one particular executive’s administration, and angered Burnet as much as the deputies.13 In 1732, the assembly refused by 56 to 1 to supply the treasury unless it could control specific appropriations. True, the house reversed itself on this issue by 55-25 in 1733 under threat of the king’s displeasure, just as it ‘submitted to’ (rather than ‘accepted of’) the Explanatory Charter by 48-32.14 But such compliance clearly occurred under duress. Only Governor Belcher began to form a party loyal to himself and thereby successfully stifled the opposition from 1735 to 1739.15 This faction can hardly be considered a court party, however, since Belcher spent much of his energy persuading Britain not to insist on the question of the permanent salary and to postpone redemption of the paper money supply. The governor had rather assumed leadership of the country faction.

The popular faction’s one-sided dominance during the interwar period is explained by the fact that leadership in the assembly was concentrated in a few powerful hands. If service on fifteen committees-which examination of the House Journals suggests is a plausible dividing line between political leaders and the rank-and-file-be taken to indicate prominence, only 27 of 104 towns represented supplied any leader at all. If a deputy is counted once for every year he attained this position, seven towns provided 61 percent of this select group. Boston headed the list with 32 percent; with rare exceptions, all four of the capital’s assemblymen appeared as leaders. Only Charlestown, Braintree, Ipswich, Salem, Northampton, and Roxbury supplied more than four percent. Certain individuals (such as Speakers Edmund Quincy of Braintree and William Dudley of Roxbury) who served repeatedly account for the importance of these towns.16

Most of the leading political figures between 1713 and 1740 belonged to an extended kinship network, centred on Boston, which embraced the first families of Massachusetts. Even the few men who adhered to the unpopular governors’ standards were related to their opponents. The famous Elisha Cooke, who founded the Boston Caucus in 1719 and led the popular party until his death in 1737, counted three of his brothers-in-law, Oliver Noyes, John Clarke, and William Paine, among his principal supporters in the house. But Clarke was also the brother-in-law of Cotton Mather, who consistently favoured the royal governor. Elizabeth Clarke, John’s sister, was married to Elisha Hutchinson, that family’s patriarch in the early eighteenth century. All the Hutchinsons except William, a Caucus supporter, favoured the prerogative. One of Cooke’s uncles was Nathaniel Byfield, a brother-in-law of Governor Joseph Dudley (1702-1715) who turned against his kinsman’s administration during its final years. If we go one step further, two of Dudley’s three daughters had married sons of councillors Samuel Sewall and Wait Winthrop while their fathers were feuding violently with the governor.17 However violent the rhetoric of peacetime political conflict, it was tempered by the fact that all the participants belonged to an elite which both the populace and representatives entrusted with the government.

Peacetime politics thus were plagued with superficial contention, but the system was essentially stable because administration was not expensive, government was stabilised through elite family participation and did not impinge on the lives of people except through request or mild taxation, and political issues rarely went beyond discussion of legislative prerogatives. But around 1740, two events shattered this political framework almost simultaneously: the currency crisis and the Great Awakening. Compelled by Britain to withdraw all except £30,000 of its £390,000 in circulation by 1741, two groups in Massachusetts tried to sidestep the order by creating private currencies-a Land Bank with province-wide support and a Silver Bank, favoured primarily by wealthy Boston merchants. The province overwhel. mingly supported the Land Bank. Only 11 of the 43 deputies who opposed the measure in 1740 were re-elected in 1741, whereas 33 of the 63 who supported it retained their seats. Opposed by Governor Belcher and both British and Massachusetts merchants, the Bank was ultimately declared illegal by Parliament, which provoked its supporters to threaten violent revolution. The situation was defused because Belcher was removed at the height of the crisis (ironically enough, because the ministry had been misinformed by his political opponents that he actually favoured the Land Bank) and was replaced by Advocate General William Shirley, who managed to liquidate the Bank to the satisfaction of most parties.18

The Awakening revived popular interest in religion at the same time that the Bank stirred up general political concern. Towns and families throughout Massachusetts split between ‘Old Lights’ who defended the traditional religious establishment and ‘New Lights’ who favoured more emotional preaching, which was to be judged by popular appeal rather than mere competence. Other differences set off the New Lights as potential threats to social order: salvation came all at once to an utterly depraved soul rather than as the culmination of ‘good works’ and socially acceptable ‘preparation’. Itinerant ministers and preachers of different denominations were welcomed by the New Lights. These innovations clearly undermined the absolute position of each community’s own established cleric. Young people, women, and the less well-to-do tended to support the Awakening. Also, three generations of high birth rates and low death rates had led to a substantial decline in economic opportunity in the province’s older communities. The Awakening provided those who were worth less in worldly terms with the means to assert their superiority over those more elevated than them in the traditional socio-economic structure. For instance, the Second Church of Boston, the Mathers’ congregation, split in two: the wealthier and older members followed ‘Old Light’ Samuel Mather when he was ousted by the younger, less affluent majority. The coincidence of overcrowding, economic distress, and a religious revival with a demonstrable social basis suggests that Massachusetts was sitting on dynamite by the early 1740s.19

That these social problems did not produce an explosion, it may be tentatively postulated, can be attributed to the outbreak of war between England and Spain in 1739 and England and France in 1744. The pressure of a common enemy redirected religious enthusiasm into another crusade, provided an outlet for young men with limited prospects, and brought ideological sparring within the General Court to an end for approximately two decades. Yet it can be argued that war did not so much solve these problems as mask them, since they re-emerged with even greater intensity in the 1760s. Furthermore, Anglo-American disagreement over the conduct of the war led to increasing popular discontent with Britain.

Massachusetts’ limited involvement in the war with Spain from 1739 set several patterns for the greater conflicts which followed. In 1740 Governor Belcher issued a call for volunteers to serve as support troops for a British fleet destined to attack Cartagena in the West Indies. The response, thanks to promises of liberal pay, bounties, and plunder, was overwhelming despite the almost total decimation of a similar New England expeditionary force in 1703. Belcher raised one thousand men instead of the six hundred requested; this produced some embarrassment when Britain only supplied arms for the number originally planned. Surviving muster rolls indicate that young men from the long-settled towns of eastern Massachusetts supplied most of the enlistments. The campaign was a total fiasco and few of the men returned, but it set a precedent which held throughout the mid-century wars: Massachusetts raised most of its forces through bounties and the inducement of receiving military pay, room, and board.20

Warfare also helped to relieve the monetary crisis. As early as October 1741, Governor Shirley had managed to persuade the ministry to revoke its instructions that all issues of paper money in excess of £30,000 must be approved by the Privy Council. When war with France broke out in 1744, all restrictions were waived for the duration of the conflict. Despite ‘the extreme heavy burden’ of which the General Court complained in 1748, Massachusetts financed the bulk of King George’s War simply by rolling the presses: in 1749, £1.9 million were extant and the currency’s value had depreciated to one-tenth of sterling.21

Finally, the war fever caused New Lights and Old Lights to bury the hatchet between themselves. Beginning with the Louisbourg expedition of 1745, Puritan millennial confidence revived for the first time since the 1630s and 40s. Conquest of the French and Indians was viewed as a prelude to the final triumph over the Anti-Christ (Popery), the universal spread of true religion, and the second coming of Christ. The millennium would come about as a capstone on the efforts of God’s chosen people, rather than as a punishment for their declension and depravity as millenarians in the intervening century, such as Cotton and Increase Mather, had feared.22

The imperatives of war resolved political tensions between the governor and the legislature in addition to defusing potential social conflict. Throughout the 1740s and 1750s, a powerful prerogative faction headed by Thomas Hutchinson and Andrew Oliver of Boston obtained nearly all the troops requested by Britain, successfully implemented a currency backed by specie in 1749, and prevented inflation throughout the French and Indian War by imposing heavy taxes to finance current expenditures. This faction first appeared in Bostonian politics in the late 1730s: following the death of Elisha Cooke in 1737, the town began to elect supporters as well as opponents of the governor to office for the first time in a quarter-century. Even though Hutchinson and Oliver sought to alter Boston’s town meeting government to a self-selecting corporation, the town recognised their administrative competence as the only alternative to the politics of the Caucus, which had wasted its energies quarrelling with governors while the town’s economy and quality of life drastically declined. Composed of relatively young men, born mostly around 1710, the prerogative faction dominated provincial politics until it was dethroned during the revolutionary crisis. 23

The rise of the prerogative faction coincided with a drastic change in the activities of the legislature. Attention shifted from resolving local problems to matters of defence. In 1745, 224 of the 324 resolves passed by the house involved provincial interests, an almost exact reversal of the ratio of general to local business of two years before. In 1757, at the height of the French and Indian War, the proportion was 202 bills to 94. Furthermore, the number of representatives involved in the house’s committee work grew dramatically. In the absence of a paid bureaucracy, and given the fact that many of the Massachusetts local justices and militia officers sat in the house, the activity of the so-called back-benchers had to increase as the legislature changed from an ideological forum and court of appeals to an organ of policy formation and public administration. Between 1740 and 1764, 70 percent of all represented towns (86 out of 123) supplied deputies who sat on more than fifteen committees per year, as opposed to 26 per cent in peacetime. Boston’s share declined to 15 percent, and no other town had more than three per cent. The responsibility of power diffused itself throughout the province as effectively as government imposed itself on the general population. No longer could most political figures be cousins, uncles, and brothers-in-law; even within Boston itself, apart from the Hutchinson-Oliver connection, few leading legislators of either faction were related.24

The prerogative’s success in the provincial sphere can in part be explained by the reason that it dominated Boston. Governor Belcher’s willingness to meet the old country faction more than halfway caused its members to dissipate their energy in a dispute between Belcher and Cooke which disenchanted many of the back-benchers in the assembly. Furthermore, as with solving Boston’s economic problems, the task of running a war required the patience and attention to detail which the free-wheeling Cooke and his followers had never possessed. Negotiations with Indians and other colonies, preparation of endless accounts and muster-rolls, and supervision of supply shipments transformed leading politicians into full-time civil servants as well. Massachusetts willingly overlooked the prerogative’s mistrust of popular government and conspicuous consumption in the face of local hardship in the light of the overwhelming necessity required by the great ‘crusade’.

Prerogative rule possessed even less savoury elements. Over three-quarters of the deputies held commissions either as justices of the peace, militia officers, or both. In addition to their pay, officers had the privilege of selling supplies to their troops. Especially recalcitrant opponents of the war could be removed from their posts by the governor with the council’s consent. Governor Shirley and his supporters also used dubious parliamentary manoeuvres-warning that British displeasure and punitive measures would follow if the war were not fought with all possible vigour, holding the legislature in session until their opponents went home, and even expelling the country faction’s most effective remaining leader-to get their way. Prerogative strength must be explained by a combination of consensus and coercion: to stress either unduly converts men like Hutchinson and Shirley into either villains or heroes, and leads to excessively partisan interpretations of provincial politics as either stable or conflict-ridden.

The manner in which Britain’s promised financial compensation for Massachusetts’ Louisbourg expenditures became a prerogative tool to obtain additional troops and funds provides an excellent example of how the lower house could be persuaded to act in spite of its own best judgment. Having launched the expedition and plunged themselves £50,000 into debt, the deputies begged ‘His Majesty’s favor and compassion … in relieving them from such part of the expenses and burden as to His wisdom should seem reasonable.’ Once the representatives put themselves in this position, Shirley could extort further grants of troops and money by threatening that if the war effort proceeded with insufficient vigour, Britain might think twice about paying for Louisbourg. When he proposed the reduction of Canada on 31 May 1746 Shirley warned that ‘a wrong step in the affair will endanger our being disappointed in our expectations’. The following July the governor impressed men who had enlisted for frontier garrison duty into the expedition contrary to the vote of the house. When the representatives refused to pay them, he obtained a reversal of this decision by promising to explain to his superiors that he was obliged to pay them from drafts on the British treasury. The house again acquiesced rather than lose all chance of receiving the Louisbourg grant.25

Tension between Shirley and the assembly also arose over the posting of soldiers and the duration of their service. Troops who had volunteered or been impressed for one theatre of war were sometimes transferred to a less attractive post, or else enlisted to obtain a more favourable one. These practices necessitated additional impressments to fill the vacated commands. The house protested in vain that ‘we have always looked upon the impressing of men even for the defence of their own inhabitants as a method to be made use of in cases of great necessity only’. A second difficulty occurred when the governor held provincial soldiers on garrison duty long after their enlistments had expired. Some men were kept at Annapolis in Nova Scotia from mid-1744 until January 1746, and the entire 3000 men Louisbourg contingent (of whom more than 900 died from exposure and disease) remained at Cape Breton from June 1745 until a long-awaited British garrison arrived in April 1746. The assembly complained that such extended service reduced ‘due confidence in the promises of government’.26

Discouragement with Shirley’s conduct of the war brought it to a halt sooner than he would have preferred. He failed to obtain a second expedition to Canada in 1747. When Louisbourg was returned to France by the Peace of 1748, the assembly commented:

‘it affords us a very melancholy reflection when we consider the extreme heavy burden brought upon the people of this province, and the small prospect there is of any good effect from it … we have been the means of effectually bringing distress, if not ruin, upon ourselves’.27

In addition to side-stepping the legislature’s wishes in mobilising forces, Shirley dealt harshly with opponents of his policies. Dr. William Douglass, the province’s only European-trained physician, attacked the governor for permitting the impressment of sailors into the British navy, allowing sanitary conditions to deteriorate at Louisbourg, and authorising the issue of more paper money in eight years to finance his schemes than all his predecessors combined over the previous fifty. In a monumental Summary, Historical and Political … of North America, which he published serially in the Boston Gazette beginning in 1747, Douglass roundly attacked Shirley’s military strategy and ‘governors in general, who may by romantic (but in perquisites profitable) expenditions, depopulate the country’. Shirley instituted a libel suit for £10,000 on behalf of the British Admiral Charles Knowles, another target of Douglass’ venom; Douglass answered with a counter-suit and ultimately won £750 in damages against the absent admiral. Shirley also sued Samuel Waldo, the Boston merchant and land speculator to whom he owed his job, for £12,000. The governor blamed Waldo, commander of the aborted Canada expedition, for failing to keep adequate accounts and thereby denying Massachusetts compensation for its efforts from the British treasury.28 Although Waldo too was ultimately acquitted, the governor’s leading opponents could count on the threat of enormous and potentially ruinous lawsuits for their pains.

After the war ended, Shirley and his supporters continued to use unsavoury tactics to persuade the assembly to adopt and maintain a specie currency. The Speaker of the House, Thomas Hutchinson, took the first step in this direction by convincing the assembly that compensation for Louisbourg would never be forthcoming unless the province pledged to use the money to sink its paper currency. However, once the money arrived, a specific plan for redeeming the outstanding bills only passed on 20 January 1749 by a vote of 40-37 after five weeks of debate. To effect this vote, Hutchinson waited until about one-quarter of the assembly had drifted away and ensured that James Allen, Shirley’s principal antagonist who had accused him of trading with the enemy, would be expelled.29

Reaction to the new currency was overwhelmingly negative. Hutchinson lost the next Boston election to Samuel Waldo by a margin of almost three to one. His house burned down, mysteriously, and the fire companies refused to put out the blaze.30 Allen published a list of the supporters of the currency plan: the next year, on 5 April 1750, the assembly responded by voting 46 to 33 to issue a new form of paper money. But once again, the hard money advocates had greater staying power. After the backcountry opponents of silver melted away, seven deputies were persuaded to change their minds and the new bills were rejected 31-28 on 20 April. In 1751 the house again voted an inflationary supply bill by 36-26. That year only the council’s adamant refusal to concur ensured the survival of a stable currency.31

The ability of the prerogative faction to outlast and intimidate the majority of the representatives caused opposition spokesmen to adopt, for the first time, the Old and New Whig ideology with which the leaders of the Revolution ultimately justified their cause. Shirley’s administration presented the novel phenomenon of a House of Representatives conducting an unpopular and costly war against the wishes not only of individuals but-as some of its messages and reversed votes made perfectly clear-against its own better judgment. It therefore became necessary for the country faction, for the first time, to detach itself from the assembly and go beyond the mere defence of the deputies’ right to make their own laws. Once the assembly itself was conceived to be an instrument of oppression, an appeal to a higher standard was required which explained how the people’s own representatives could betray their constituents.

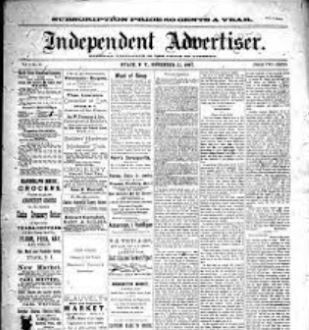

Whig ideology suited the Massachusetts situation perfectly. The Independent Advertiser, America’s first anti-war and protest newspaper was founded one month after the great anti-impressment riot of 17-20 November 1747 by the twenty-five-year-old Samuel Adams, among others.32 These opposition writers cited John Locke to argue that a government which failed to protect the inhabitants’ ‘lives, liberties, and estates’ by forcing them to fight against their wishes, impressing them into the navy, and taxing them oppressively could be opposed legitimately–even violently. Similarly, the New Whig ideas of William Trenchard and John Gordon were adapted to explain how only a morally and fiscally corrupted government would so betray its people, and that only an equally corrupted people would tolerate such oppression. The Advertiser blamed the war on representatives who had been corrupted by Sir Plume (Governor Shirley) and his ‘prime minister’ Alexander Windmill (Thomas Hutchinson) by being given military commissions, which paid officially from about £50 sterling per year for a captain to about £80 for a colonel. These, however, also entitled them to supply and pay their men and thereby opened the door for padded accounts and illegal profits.33 Most of the complaints of corruption were directed against Shirley personally, who was alleged to have made an enormous sum of money by being granted the right to raise a royal regiment of colonials to garrison Louisbourg. New Whig ideology made sense in wartime because, unlike peacetime, real opportunities for making large sums of money in government service existed.34

There is little hint in The Independent Advertiser that the French and Indians were a real threat to Massachusetts: the ‘Popish’ refurbishing of King’s Chapel by Shirley and the Boston Anglican community was a far greater menace. Colonists constantly denounced England as a den of iniquity and corruption instead. After the mother country gave Cape Breton back to France,35 the most extreme critique of the war and its engineers occurred:

Why is the security of the brave and virtuous … given up to purchase some short-lived and precarious advantages for lazy-f[oo]ls and idle All[ie]s? The security was purchased with the blood of the former and sacrificed to the indolence of the latter. The first won it by bravery; the latter forfeited it by Tr[e]ach[e]ry and Cow[ar]dice. As if our Min[i]stry … had determined to counteract the essential laws of equity, as much as possible, as they have done the rules of policy and prudence.

Reaction to British and prerogative policies not only took verbal form: wartime crowds began to focus on political issues. Between the Glorious Revolution and the 1740s, political violence in Massachusetts was committed by individuals against individuals-a bomb thrown through Cotton Mather’s window, a pot shot taken at Samuel Shute, an assault against Elisha Cooke -whereas crowds restricted themselves to remedying local emergencies which could not conveniently be handled in courts of law. For example, mobs tore down bawdyhouses and market stalls under construction in the 1730s, and stopped ships trying to export food during shortages from sailing. A corrupt and brutal jailor found himself the target of a prison riot. Beginning in the 1740s, however, mobs for the first time directed themselves against imperial power and clashed with British rather than local authorities. The occasion was naval impressment: despite an Act of Parliament of 1707 forbidding impressment in American waters without the consent of local authorities, and in spite of Massachusetts’ willingness to authorise the impressment of non-native seamen who happened to be in the province, British captains provoked hostility by their disregard for such points of law. Angered that their sailors deserted with local connivance, they sometimes simply impressed people indiscriminately and then sailed for the West lndies. In 1741, Captain James Scott seized over forty men and narrowly escaped with his life. A press gang killed two veterans of the Louisbourg campaign in 1745 for resisting efforts to seize them; in 1747 virtually the entire populace of Boston held many of the officers in Commodore Knowles’ British fleet hostage pending the release of forty-six impressed men. Instead of negotiating Knowles threated to bombard Boston while a mob of several thousand people surrounded the governor’s mansion and General Court to press their demands. The Independent Advertiser justified such violence as the legitimate response to lawless acts of nominally lawful authorities. Where the government could not protect its inhabitants, ‘they have an undoubted right to use the powers [of self-defence] belonging to that state [of nature]’. Just before the paper closed down, it responded to critics of the Knowles Riot, ‘that the sober sort, who dared to express a due sense of their injuries, were invidiously represented as a rude, low-lived mob’.36

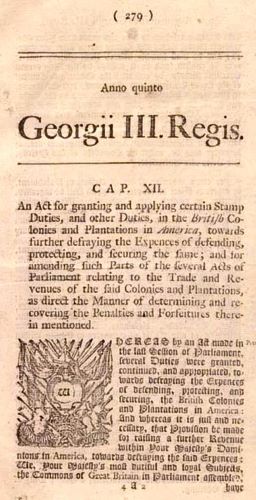

The French and Indian War revived the same tendencies manifested in King George’s War. The province was even more cooperative and self-sacrificing, but the prerogative faction’s efforts to coordinate provincial and imperial policy again provoked resentment against British officials. Taxes, which the province had considered heavy at under £10,000 sterling in the 1740s, rose to £60,000 sterling or more from 1756 to 1760 and remained at over £30,000 for the rest of the provincial period.37 Protesting against the fact that most of this money was raised from land taxes, the rural majority in the assembly struck back at the Boston-based prerogative faction by passing the infamous Excise Tax of 1754 and a Stamp Tax in 1755 (remarkably similar to the one Britain would later impose on the colonies) to shift the tax burden towards the urban communities. The new excise differed from the province’s long-standing tax on liquor by taxing the consumption of spirits by individuals rather than the amount sold by retailers. To discover the quantity, the government appointed excise farmers who could then hire deputies to demand an account ‘of all and every persons whomsoever in this government, of all the wine, rum, and brandy, and other distilled spirits expended by them ( on oath if required)’; a penalty of £10 was established for false swearing. The prerogative faction and the Boston community joined forces (Boston was already paying 20 percent of the taxes even though it had under 10 percent of the population) to protest against this ‘Total Eclipse of Liberty’ and ‘Monster of Monsters’, as two pamphlets attacking the bill were entitled. Governor Shirley, who signed the bill under protest, himself took up the natural rights argument that had previously been used by pis opponents, criticising the tax as ‘altogether unprecedented in the English governments’ and ‘inconsistent with the natural rights of every person in the community’. The country’s revenge on the court faction was short-lived: the people of the province were so angered by the excise that only 19 of the 52 deputies who approved it were re-elected, whereas 10 of the 17 who opposed it (they came from the Boston area, Salem, Marblehead, Plymouth, Maine) retained their seats.38

Taxes and economic difficulties during the French and Indian War rose to unprecedented heights. The legislature placed embargoes on exports of food which compelled farmers to sell provisions to British and American military commissaries at lower than usual prices; British commanders-in-chief also prohibited colonial overseas shipping intermittently when they considered trading with the enemy to be excessive. These restrictions continued until 1763: Massachusetts’ new governor Francis Bernard (1760-1769) joined the legislature and protested to General Jeffrey Amherst that ‘this public spirited province can ill afford to lose the small trade remaining to it’ and that in any event illegal trading simply did not exist in Massachusetts. Things became so bad in 1758 that sixteen leading Bostonian merchants, all of whom paid taxes of between £95 and £540 per year, threatened to leave the province and take their business elsewhere. Bernard later argued that British taxation was unjust because Massachusetts itself had spent ‘an immense sum for such a small state, the burden of which has been grievously felt by all orders of men.’39 Economic hardship drove a large number of people into bankruptcy. To combat this problem, in 1757 the legislature passed the first major bill reforming the treatment of bankrupts in Massachusetts history. Instead of being forced to forfeit their entire estates and possibly go to debtors’ prison, all persons who advertised bankruptcy in the Boston newspapers, did not try to hide any of their wealth, and permitted their affairs to be investigated by commissioners could begin life with a clean slate. Insolvents able to pay at least half their debts could retain five per cent of their wealth up to £200; those able to pay two-thirds could keep 7½ percent up to £250; anyone who could satisfy three-fourths of the claims against him was allowed ten per cent of his estate under £300. The reform was timely: joyous news of British victories were always tempered by lists of the financially distressed in the same issues of the province’s journals. For instance, twenty-eight persons filed for bankruptcy the week Louisbourg was recaptured in 1758. As late as February 1765 the default of Nathaniel Appleton on £189,000 set off a chain reaction because his creditors in turn could not pay their debts.40

In addition to shouldering these burdens, Massachusetts had to bear with the arrogance of British commanders-in-chief who seemed determined to infringe provincial rights and sensibilities to the maximum while winning the war. Naval impressment continued, and Massachusetts again protested against this grievance in vain.41 Britain and Massachusetts disagreed over the number, disposition, and ability of the provincial soldiers. Each year, the prerogative faction struggled long and hard to obtain the deputies’ endorsement of the full number of troops requested by Britain. Even then, the assembly confined the troops to particular posts and enlisted them for limited periods of time which coincided poorly with military necessity. As Lord Loudoun, commander-in-chief during 1757 and 1758, complained at an intercolonial conference:

‘The confining of your men to any particular service appears to me a preposterous measure. Our affairs are not in such a situation as to make it reasonable for any colony to be guided by its own particular interest’.

Other problems included soldiers sent to the frontier without arms; men enlisting and deserting several times to collect bounties; and officers and sutlers profiteering from the right to supply men with provisions. The province’s insistence that impressment should only be used as a last resort ensured that each year’s supply of men took several months to be mustered. Recruiting parties met with resistance in Boston and Marblehead. Loudoun also wanted colonial troops to be led by British officers aad subjected to regular army discipline. His insistence that no provincial officer should rank higher than a British captain threatened local autonomy and insulted the province’s military capability.42

When in camp, British officers frequently assigned colonials only the most onerous and demeaning work instead of committing them effectively to battle. General James Wolfe expressed the general British attitude:

‘The Americans are in general the dirtiest, the most contemptible, cowardly dogs that you can conceive. There is no depending upon them in action. They fall down in their own dirt and desert by battalions, officers and all’.43

The most spectacular instance of Anglo-American animosity was the quartering dispute of December 1757 and January 1758. Massachusetts gladly offered to billet the troops for the winter, but Loudoun insisted that any legislative action was unnecessary because the British Quartering Act of 1694, which gave commanders such authority in England, applied to the colonies. The assembly could not see the reason for his indignation:

‘We are really at a loss what steps to take to terminate this affair since His Lordship does not seem dissatisfied so much from the insufficiency of what we have done, as from the matter of its being done by a law of the province.’

Loudoun, on the other hand, argued that if quartering were discretionary rather than automatic, ‘my acquiescence under it would throw the whole continent into a turmoil, from South Carolina to Boston, and turn three-quarters of the troops at once into the streets to perish’. At stake was whether the commander-in-chief could conduct the war independently of local interference. Loudoun complained that ‘even if the town of Boston was attacked, it would not by their rule be in my power to march the troops to its relief’. He then threatened that if things were not settled he would ‘instantly order into Boston the three battalions from New York, Long Island, and Connecticut, and, if more are wanted, I have two in the Jerseys at hand besides those in Pennsylvania’. Loudoun also hinted that Britain would not think it reasonable to pay the colonies for their ‘very extravagant’ war expenses if they did not even provide lodging for the troops sent to protect them. 44

While it lasted, the French and Indian War provoked less discontent than King George’s: the country faction did not oppose any expeditions or the war itself this time, only the proportion to be shouldered by Massachusetts rather than by Britain. However, the peculiar manner in which the war ended led to increased political strife, both within Massachusetts and between Massachusetts and Britain, after hostilities were concluded. With respect to the New England colonies, the French menace ended forever when British forces raised the Union Jack over Quebec in 1759. But the war dragged on four more years, both in the West Indies and on the frontier of the middle and southern colonies. Britain expected all the mainland colonies to contribute soldiers for frontier duty so that the more valuable redcoats could be sent to Europe or the islands. Thanks largely to persuasive speeches by Massachusetts’ popular new governor Francis Bernard, the Bay Colony complied and supplied 3000 soldiers per year until 1763 and also sent 700 men to the Ohio Valley in the wake of Pontiac’s rebellion as late as 1764.45 Because the war ended in 1759 in the Northeast while elsewhere it continued until 1764, Massachusetts felt little urgency or need for further sacrifices, and yet she was still required to maintain embargoes, levy taxes, and raise troops.

These difficulties were exacerbated by Britain’s plans for imperial reorganisation which were implemented before the war’s end. Despite the embargoes and taxes suffered by the Boston merchant community, British customs officials in Boston could not leave well enough alone and provoked the famous challenge to their general search warrants, the Writs of Assistance Case in 1761. The Sugar Act and Proclamation of 1763 were promulgated while Massachusetts still had several thousand men in service.

The manner in which Parliament’s promised reimbursement finally arrived did not help matters. Massachusetts always insisted that its exertions went far beyond those of the other colonies. As a result the province was entitled to special treatment. This was not forthcoming: Jasper Mauduit, the province agent in the early 1760s, did little to force the issue. He urged acquiescence with British policy: since the other colonies were content with requesting compensation for about half their wartime expenditures, Massachusetts would appear ‘in a very disadvantageous light to present a petition to Parliament setting forth that we are content with nothing less than the whole of ours’. Massachusetts ultimately received only £390,000 out of some £818,000 spent.46

Internal strife also broke out while the war was ending. Religious controversy between the province’s Congregational establishment and a small but influential community of wealthy Anglicans began in 1761. The latter belonged mostly to wealthy Boston area families which had strongly supported and profited from the war. Charles Apthorp, a young Anglican cleric, established a ‘mission’ at Cambridge, causing many of the clergy to think that the long-feared Anglican bishopric was finally upon them.47 In Maine, two land companies, the Kennibeck and the Waldo heirs, the former composed largely of future patriots, the latter of future loyalists, squabbled for control of vast tracts of land.48 Western Massachusetts, which staunchly supported a maximum war effort, began to develop a sense of regional consciousness and in 1762 tried unsuccessfully to obtain its own college.49 These disputes tended to coincide with divisions between the prerogative faction and its opponents: once war ended, regional, religious, and economic differences between the two factions began to take political form.

The conclusion of war also brought the problem of underemployment and overcrowding to the fore again. Massachusetts had developed something approaching a European standing army. Youths from overcrowded towns and lower class men enlisted year after year under the command of an officer class consisting of the province’s leading men.50 Battle deaths had also helped to alleviate population pressure. But beginning in 1765, the first year since 1754 Massachusetts and its fellow colonies did not muster forces for battle, the situation drastically changed. A postwar decline in overseas trade and the catastrophic drought of 1763-4 let loose an unprecedented wave of rootless persons throughout the province.51 Boston’s Warning Out records (which do not indicate who was forced to leave town, but only listed entering migrants who would then not be eligible for public relief if they became destitute) show that migration increased astronomically at precisely this time. Beginning in 1745, the first year systematic records were kept, and for the following two decades of war, migration to Boston was primarily female and mostly from Massachusetts. But in 1765, not only did the number expand greatly, but the migrants were mostly male, many men with families, and came from both Massachusetts and overseas. Eighty percent of all male migrants to Boston from 1745-1773 arrived between 1765 and 1773. Total migration rose each decade: 458 households (1745-1755); 925 (1755-1765); 2479 (1765-1773).52 The presence of so many additional single men in Boston undoubtedly swelled the size and added to the vigour of the Boston mob. Once again, during the revolution itself, in eastern Massachusetts long term military service was largely confined to young men who did not have sufficient wealth to pay taxes or were still dependent on their fathers.53 But during the decade of 1765-1775, many men had nowhere to go except into the revolutionary movement.

The most notable political effect of the ending of the war was the swift demise of the prerogative faction. By 1766, its leading members were purged from the council seats some of them had held for decades. Its strength dwindled quickly from approximately half the house in 1765 to almost zero by 1768. Massachusetts would tolerate the leadership of a Thomas Hutchinson during wartime when administrative skills and capacity for hard work were of the utmost importance. Sacrifices in the interest of the common cause were tolerable, and even Hutchinson and his cohorts protested against such enormities as naval impressment and the quartering act. Once war ended, however, restrictions on Massachusetts’ trade, tighter and possibly corrupt enforcement of customs regulations, and taxation by Britain rather than the province itself all appeared to undermine the prerogative’s contention that Anglo-American interests were compatible.

The faction which had dominated Massachusetts for a quarter-century was swept away with remarkable ease between 1761 and 1768 largely because it had a distorted conception both of itself and of Massachusetts politics. Although most of its leaders were initially Bostonians, they disliked town-meeting politics and preferred to spend as little time in town as possible, moving to their suburban imitations of English country houses and socialising among themselves, instead of staying in contact with the common folk.54 In consequence, they deluded themselves into thinking that they were entitled to hold office through noblesse oblige; they did not perceive it as a reward bestowed on them for their competent administration of the war in spite of their profiteering and aloofness. Once the war ended the sole basis of their support vanished.

The inability of the prerogative to put up a better fight can also be traced to the roots of its power. Believing that the correct role of the populace in government was passively to sanction the decisions of an administrative elite, they could not effectively use newspapers, harangue crowds, or cater to popular support through organisations such as the Boston Caucus. They had little experience in such matters, considered ‘politics’ as opposed to administration both a social evil and beneath their dignity, and were simply too set in their ways to adjust to a new world of politics as they approached in most cases the age of sixty.55

The prerogative’s wartime strength was also translated into post-war weakness in another way. The opposition had been hampered throughout the war by weak or self-serving leaders; in the early 1760s, for example, Benjamin Pratt and John Tyng were respectively bought off with the Chief Justiceship of New York and an inferior court post in Middlesex County.56 As a result of the default or death of the old popular party’s leaders, a new one arose to express general indignation. Composed primarily of much younger men without previous personal or familial ties to provincial politics, the new country faction drew its strength from journalistic skills, Boston machine politics, and the ‘Boston mob’. It used extreme rhetoric which equated its enemies with the anti-Christ and predicted the total suppression of American liberty if the corrupt opposition were not totally destroyed. Coming from outside the legislature, the new politics had to employ more extreme means to resist British policy in Massachusetts than in other colonies simply because in no other province did the people have to be persuaded to purge the legislature of such a strong pro-British faction.

One of the most potent arguments the revolutionaries advanced to resist British policy in Massachusetts was that it was both unfair and unnecessary because the province had indeed borne more than its share of the war. In Massachusetts requisitions had most certainly worked. For instance, when James Otis protested against the Stamp Act with his ‘Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved’, he not only appealed to natural rights, but also to past experience:57

We have spent all we could raise, and more; for notwithstanding the parliamentary reimbursements of part, we still remain much in debt. The province of the Massachusetts I believe, has expended more men and money in war since the year 1620, when a few families first landed at Plymouth, in proportion to their ability, than the three Kingdoms together. The same, I believe, may be truly affirmed of many of the other colonies, though the Massachusetts has undoubtedly had the heaviest burden.

Otis’s argument was taken up by other colonials. In 1764 the New York assembly protested against British taxation because ‘in many wars we have suffered an immense loss of both blood and treasure, to repel the foe, and maintain a valuable dependency on the British crown’. And when Benjamin Franklin appeared before the House of Commons in February 1766 to make his famous false distinction between the colonies’ objection to internal taxes and their willingness to acquiesce in external, he was right on the mark when he argued that ‘the colonies raised, clothed, and paid, during the last war, near 25,000 men, and spent many millions’.58

Even leading Massachusetts Tories agreed with this analysis although not with the deduction that resistance and revolution were the only correct responses. Thomas Hutchinson argued forcefully though privately that the Stamp Act was unjust because the colonies had contributed more men to the ‘Great War for Empire’ in proportion to their population than the mother country. Secondly, the colonies had defended themselves for the century before 1754 without much British assistance, and through their own exertions had increased the strength and prosperity of the empire. Third, whatever contribution the colonies had made as a whole, Massachusetts’ efforts deserved special mention: ‘No other government has been at any expense to set against this’, with the result that during the war ‘the public debt increased annually thirty or forty thousand pounds lawful money.’ Finally, Canada was of no economic value to the colonies and would greatly depreciate existing colonial land values.59 Loyalist Isaac Royall, a wealthy West India planter who had lived in Charlestown and Medford since 1737, similarly remonstrated with Lord Dartmouth in 1774 that ‘this province Sir has always been foremost even beyond its ability and notwithstanding the present unhappy disputes would perhaps be so again if there should be the like occasion for it in promoting the Honour of their King and Nation. Witness their twice saving Nova Scotia from falling into French hands, the reduction of Louisbourg … and many other expensive and heroic expeditions against the common enemy’.60

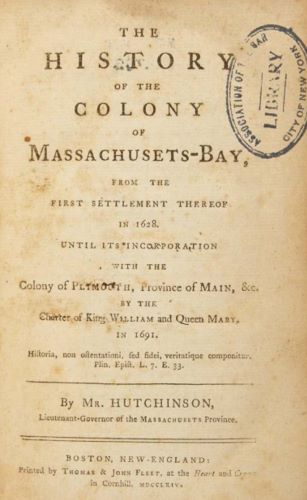

Yet the loyalists also insisted that whatever the colonists’ own exertions, British aid had still been necessary. Even if taxation were unfair or onerous, the indisputable fact remained that without Britain Canada could not have been taken. In his History of Massachusetts, Hutchinson argued the opposite position to that which he adopted in his letter on the Stamp Act. Without help, the colonies ‘would have been extirpated by the French’, and even at Louisbourg in 1745, the deciding factor was ‘the superior naval power of Great Britain’. Hutchinson agreed with the patriots that the mother country had no altruistic motives for aiding the colonies-‘fear of losing that advantageous trade’ rather than ‘paternal affections’ was the true cause of intervention. But Britain had undeniably ‘expended a far greater sum’ rescuing the colonies during the final war ‘than the whole property, real and personal, in all the colonies would amount to’. Therefore, ‘in a moral view, a separation of the colonies which must still further enfeeble and distress the other parts of the empire, already enfeebled by exertions to save the colonies’, was reprehensible.61 Of course, the revolutionaries argued that Hutchinson and his fellow loyalists’ real motive for defending British policy was that their own careers and pocketbooks had benefited greatly through their participation in the war, whereas many of their countrymen had lost sizeable portions of their estates or even their lives.

A persuasive case can be made that serious popular resentment against British imperial policy-which had been loosely enforced during the age of ‘Salutary Neglect’ between Queen Anne’s and King George’s Wars-occurred because in two decades Massachusetts had launched a war effort which to be effective required a major transformation of its political system. War greatly increased the role of government in Massachusetts society and transformed the nature of the General Court. Increased taxation, regulation of the economy in the form of food embargoes and requisition of needed supplies, and the drafting of perhaps a fifth of the male population into the army and navy characterised military policy in mid-eighteenth century Massachusetts. To manage King George’s and the French and Indian Wars, the house’s committee work involved a large majority rather than a small minority of representatives. War proved a centralising experience in that the legislature no longer spent most of its time reacting to petitions from the towns and inhabitants and then settling disputes. Beginning in the 1740s and 1750s, deputies from throughout the province, not just a few leading men from Boston and some of the larger towns, initiated and shaped government policy instead of merely voting on issues laid before them by the leadership.

Perhaps even more importantly, as Lawrence Henry Gipson has noted, the American Revolution was an aftermath of the ‘Great War for Empire’. Gipson stresses that Britain’s effort to regulate the colonies originated in unsolved problems of the Anglo-American connection (frontier defence, trading with the enemy, effective inter-colonial coordination of forces) which seriously hampered the war effort. Had not Canada fallen to the British, the Americans would still have depended on the mother country for defence and could not have rebelled.62

But the revolution was also an aftermath of Massachusetts’ war for empire. Since the 1740s, the dominant faction in the province, led by men such as Hutchinson and Oliver, had staked its fortunes on whole-hearted American cooperation with British war measures. Functioning as full-time civil servants for years on end, they continued to support submission to post-war impositions even when the military necessity which had compelled such docility in the past had vanished. Convinced that the population as a whole lacked the knowledge and competence to govern itself, the future loyalists lacked any understanding that the successful careers and cordial relationships they had enjoyed with British officials during the war were not typical. They were not insensitive; they sought to alleviate impressment and imperial taxation. But if Britain proved adamant, they always counselled forbearance rather than resistance. Estranged from their suffering country-men, they emerged in the revolutionary decade as a government without a country.

Endnotes

- William Pencak is Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Humanities, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. Much of the article is adapted from his dissertation, ‘Massachusetts Politics in War and Peace, 1676-1776’ (Columbia University, 1978). A revised version will be published by Northeastern University Press. He wishes to thank Ralph Crandall, Jack P. Greene, Alden T. Vaughan, and Chilton Williamson for their assistance.

- Boston Gazette, 21 May, 1754.

- See generally Charles Tilly, ed., The Formation of the Nation State in Western Europe (Princeton, 1975), esp. 5-83.

- Good accounts of Anglo-American relations during the French and Indian War are Lawrence Henry Gipson, The British Empire Before the American Revolution 15 vols. (New York, 1948-1974); Stanley Pargellis, Lord Loudoun in North America (New Haven, 1933); and Alan Rogers, Empire and Liberty: American Resistance to British Authority, 1755-1763 (Berkeley, 1974).

- Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts Bay (Boston, 1919), XXII, 17, 84, 99, 110, 116, 153; XXIII, 26, 45, 110 (hereafter cited as House Journals); Gipson, British Empire, VII, 159-163; 316-24; IX, eh. iii; Jack P. Greene, ‘Social Context and the Causal Pattern of the American Revolution: A Preliminary Consideration of New York, Virginia, and Massachusetts’, (unpublished paper delivered at the Colloque Internationale du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique: La Revolution Americaine et !’Europe, February 1977), 6.

- Accounts of the Louisbourg campaign may be found in John A. Schutz, ‘Imperialism in Massachusetts During the Governorship of William Shirley, 1741-1746’, Huntington Library Quarterly, XXII (1960), 217-36; and Douglas Leach, ‘Brothers in Arms’!-Anglo-American Friction at Louisbourg, 1745-1746′, Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings, LXXXIX (1977), 36-54.

- Michael Zuckerman, Peaceable Kingdoms: The New England Towns in the Eighteenth Century (New York, 1970), 35.

- Abner C. Goodell and Ellis Ames, eds., The Acts and Resolves of the Province of Massachusetts Bay (Boston, 1869-1922), III 1107-51; IV, 1079-1116 for index of taxation and fiscal acts; for resolves for 1743, see XIII (Hereafter cited as Acts). Conversion of pounds Massachusetts to pounds sterling follows William Douglass, A Summary … Historical and Political … of North America (London, 1755), I, 493, and Historical Statistics of the United States (Washington, 1960), 771. After 1750 four pounds Massachusetts equalled three pounds sterling.

- House Journals, II, 228-33; VII, 450 ff; various letters for 1724–1726 in the Belknap, Pepperrell, Cushing, Colman, and Saltonstall Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society; Albert C. Matthews, ‘The Acceptance of the Explanatory Charter’, Colonial Society of Massachusetts Publications, XVII (1913), 389-400.

- House Journals, VII, 229; VIII, passim, esp. 140, 163.

- Ibid., VIII, 251-435; IX, 1-81, passim; various letters of William Burnet and Jonathan Belcher to Lords of Trade and the Duke of Newcastle in W. Noel Sainsbury et. al., eds., Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series (London, 1869), XXXVI-XLII (hereafter cited as CSP); Lords of Trade to Privy Council, 26 Aug. 1735, ibid., XLII, no. 82.

- House Journals, X, 104, 123,256,415; XI, 67, 73, 93, 228, 309; Belcher to Newcastle, 26 Dec. 1732 and 19 May 1733, CSP, XXXIX, no. 285; XL, no. 170.

- William Dummer to Duke of Newcastle, CSP, 15 Sep. 1729, XXXVI, no. 904; Benjamin Prescott to John Chandler, 23 June 1729, MsC. 2041, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Mass.

- House Journals, VI, 73, 93, 278, 309; Massachusetts Archives, Office of the Secretary of the Commonwealth, State House, Boston, XX, 248-9. 15. John A. Schutz, ‘Succession Politics in Massachusetts, 1730-1741’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. XV (1958), 508-20.

- Pencak, ‘Massachusetts Politics’, 445-53 for names of house leaders and statistical tables.

- Information on kinship connections among the elite are most conveniently found in the appropriate biographies in Oliver O. Roberts, The History of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company (Boston, 1854-8), I, II; and John L. Sibley and Clifford K. Shipton, Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College (Cambridge, 1873), III-VJIJ.

- Good descriptions of the crisis are found in Andrew M. Davis, Currency and Banking in Massachusetts Bay (New York, 1901), I, 111-51; II, 102-218; ‘Boston Banks and those who were Interested in Them’, New England Historic Genealogical Register, LVII (1903), 279-81; and ‘Provincial Banks, Land and Silver’, Colonial Society of Massachusetts Publications, III, (1905-07) 2-41; George A. Billias, Massachusetts Land Bankers of 1740 (Orono, Me., 1954); For specific information see House Journals, XVIII, 42-8, 185-6; Thomas Hutchinson to Benjamin Lynde, 12 Aug. 1741, in Fitch E. Oliver, ed., Diaries of Benjamin Lynde and Benjamin Lynde, Jr. (Boston, 1880), 222-3.

- J. M. Bumsted, ‘Revivalism and Separatism in New England: The First Society of Norwich, Connecticut, as a Case Study’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd. ser., XXIV (1967), 588-612; Philip Greven, ‘Youth, Maturity, and Religious Conversion: A Note on the Ages of Converts in Andover, Massachusetts, 1718-1744’, Essex Institute Historical Collections, CVlll (1972), 119-34; John C. Miller, ‘Religion, Finance, and Democracy in Massachusetts’, New England Quarterly, VI (1933), 29-58. l am indebted to Frank Granato, in a seminar paper written at Tufts University, 1979, for the information on the Second Church of Boston. For overpopulation, see Philip Greven, Four Generations: Land, Population, and Family in Colonial Andover, Massachusetts (Ithaca, 1970); Kenneth Lockridge, ‘Social Change and the Meaning of the American Revolution’, Journal of Social History, VI (1973), 403-39.

- House Journals, XVIII, 103; Jonathan Belcher to William Shirley, 12 July 1740, Belcher Papers II, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, 6th. ser. VII, 360; William Shirley to Duke of Newcastle, 4 Aug. 1740, in C. H. Lincoln, ed. Correspondence of William Shirley (New York, 1912), I, 24-6. For a profile of the soldiers, see Myron Stachiw’s excellent introduction to the forthcoming Massachusetts Officers and Soldiers During French and Indian Wars, 1722-1743, to be published by the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

- Shirley to Newcastle, 17 Oct. 1741, 23 Jan. 1742, and to Lords of Trade, 10 Aug. 1744, Shirley Correspondence, I, 76, 80, 140; Lords of Trade to Shirley, 9 Sep. 1744, ibid., 144.

- See, among other sources, Nathan O. Hatch, ‘The Origins of Civil Millennialism in America: New England Clergymen, War with France, and the Revolution’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd. ser., XXXI (1974), 417-22; Alan Heimert, Religion and the American Mind from the Great Awakening to the American Revolution (Cambridge, 1966), 82-4; George A. Wood, William Shirley: Governor of Massachusetts, 1741-1756 (New York, 1920), 169-70; 275-6.

- G. B. Warden, Boston, 1689-1776 (Boston, 1970), eh. vii; William Pencak and Ralph Crandall, ‘Metropolitan Boston Before the American Revolution: An Urban Interpretation of the Imperial Crisis’, (unpublished paper delivered at the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, February 1979).

- See n. 8, 16, 17 above. Many leading supporters of the prerogative who had withdrawn from politics-especially those who became Anglicans-were related. But they exercised no influence in the legislature.

- House Journals, XXI, 198; XXII, 162, 182; XXIII, 42.

- Ibid., XXII, 207, 246, 252.

- Ibid., XXV, 37, 52, 66; XXVI, 307-8.

- John Noble, ‘The Libel Suit of Knowles v. Douglass, 1748, 1749’, Colonial Society of Massachusetts Publications, I (1895-7), 213-40; quotation from The Independent Advertiser, 4 July 1748; William Shirley to Samuel Waldo, 28 June 1748 and 7 July 1748; Waldo to Shirley, 28 June 1748; The Case of Waldo vs. Shirley, 22 April 1749; and Waldo to Christopher Kilby, 24 April 1749; all in Henry Know Papers, L, Massachusetts Historical Society.

- House Journals, XXV, 116, 148, 150, 157; James Allen, Letter to the Freeholders and Other Inhabitants of Massachusetts Bay (Boston, 1749).

- Thomas Hutchinson, ‘Hutchinson in America’, 58, 59, Egremont Mss. no. 2664, British Museum, Microfilm at Massachusetts Historical Society; Hutchinson to Israel Williams, 17 May 1749, Israel Williams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

- Allen, Letter to Freeholders; House Journals, XXVIJ, 35, 47, 56, 62, 97, 198, 234; XXVIII, 42, 52, 56, 69.

- For a general discussion of the riot and its aftermath, see John Lax and William Pencak, ‘The Knowles Riot and the Crisis of the 1740s in Massachusetts’, Perspectives in American History, X (1976), 153-214.

- For these nicknames, see The Independent Advertiser, 27 March, 1 April and 21 Nov. 1748. For salaries, see, for example, Acts, IV, 218; for government contracts, William T. Baxter, The House of Hancock: Business in Boston, 1724-1775 (Cambridge, 1950), 92-110; 118-23; 129-41; 150–6; 253-5. Soldiers in out-of-province military expeditions were not liable to be sued for debt, a further inducement to enlist.

- For a similar interpretation of why an ideology stressing government corruption appeared at this time, see Jack P. Greene, ‘Political Mimesis; A Consideration of the Historical and Cultural Roots of Legislative Behavior in the British Colonies in the Eighteenth Century’, American Historical Review, LXXV (1969), 337–67.

- The Independent Advertiser, 4 Jan., 10 Oct. and 14 Nov. 1748; 17 July, and 17 Aug. 1749.

- See Lax and Pencak, ‘The Knowles Riot’, for discussions of these mobs and bibliographical footnotes. Quotations from The Independent Advertiser, 8 Feb. 1748 and 5 Dec. 1749.

- Seen. 8 above.

- House Journals, XXX, 43; XXXI, 38, 63-72; 202-3, 283-8; XXXII, 10, 56-9, 340-53; XXXIII, 294, 304, 307. For a discussion of the pamphlet literature see Paul Boyer, ‘Borrowed Rhetoric: The Massachusetts Excise Controversy of 1754’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd, ser., XXXI (1964), 328-51. For Boston’s tax problems, see Warden, Boston, eh. vii., and William Pencak, ‘The Social Structure of Revolutionary Boston: The Evidence From the Great Fire of 1760 Manuscripts’, forthcoming in The Journal of Interdisciplinary History.

- For embargoes, see, for example, House Journals, XXXII, 87, 93, 249, 305, 404; Francis Bernard to Jeffrey Amherst, 30 May, 2 June, 29 Aug. and 5 Sep. 1762, Bernard Papers, II, 155, 157, 280, 282, Sparks Manuscripts, Houghton Library, Harvard University; Bernard to Lords of Trade, 1 Aug. 1763, Bernard Papers, III, 162; Massachusetts Archives, LV, 301.

- Acts, IV, 29-38; Francis Bernard to Lords of Trade, 18 April 1765, Bernard Papers, III, 203; Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in Revolt (New York, 1955), 252-3.

- Impressment during the French and Indian War is discussed in William Pencak, ‘Thomas Hutchinson’s Fight Against Naval Impressment’, New England Historic and Genealogical Register, CXXXII (1978), 25-36.

- Lord Loudoun to {Massachusetts House of Representatives), 29 Jan. 1757, Israel Williams Papers; House Journals, XXXV, 351f; Thomas Hutchinson to Loudoun, 21 Feb. 1757, Loudoun Papers, Huntington Library, San Marino, California, photostat at the Massachusetts Historical Society; various letters in Massachusetts Archives, LVI, Pargellis, Lord Loudoun, 175–6; 185–6; 214–5; 269-78; John A. Schutz, Thomas Pownall: Defender of American Liberty (Glendale, California, 1951), 125, 130.

- Quoted in Rogers, Empire and Liberty, 63.

- Lord Loudoun to Governor Thomas Pownall (1757-1760), 8 and 15 Nov., 8 Dec. 1757, Massachusetts Archives, LVI, 256–66; Pownall to Loudoun, 26 Dec. 1757, ibid., 278, 286; House Journals, XXXIV, 208, 256.

- House Journals, XXXVII, 250; XXXVIII, 302; Francis Bernard to Lords of Trade, 17 April 1762, Bernard Papers, II, 180.

- Jasper Mauduit to Massachusetts House of Representatives, 8 Feb. 1763, Mauduit Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, LXXIV (1918), 100; Gipson, British Empire, IX, eh. ii.

- Carl Bridenbaugh, Mitre and Sceptre: Transatlantic Faiths, Ideas, Personalities, and Politics, 1689-1775 (New York, 1962), eh. vii; Mauduit Papers, passim, esp. 30, 76, 104–19; Francis Bernard to Richard Jackson, 23 Jan. 1763, Bernard Papers, II, 249-50; for families which profited from the war, see Gary Nash, ‘Social Change and the Growth of Pre-Revolutionary Urban Radicalism’, in Alfred E. Young, ed., The American Revolution, (DeKalb, Ill., 1976), 21-3.

- Warden, Boston, 356–57; Gordon E. Kershaw, ‘Gentlemen of Large Property and Judicious Men’: The Kennebeck Proprietors, 1749-1775 (Somersworth, N. H., 1975); also see various documents in Henry Knox Papers, L-LI, Massachusetts Historical Society.

- Henri Lefavour, ‘The Proposed College in Hampshire County in 1762’, Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings, LXVI (1936-41), 53-80; Mauduit Papers, 70-3; Oxenbridge Thacher to Benjamin Pratt [1762), Thacher Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

- John Shy, A People Numerous and Armed (New York, 1976), 30-1, 173.

- Joseph Ernst and Marc Egnal, ‘An Economic Interpretation of the American Revolution’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd. ser., XXIX (1972), 3-32; Anne Cunningham, ed., Diary and Letters of John Rowe, (Boston, 1903), 61, 67-70; Warden, Boston, eh. viii.

- Warning Out Records in Overseers of the Poor Mss., Massachusetts Historical Society. These themes are developed further in William Pencak, ‘The Revolt Against Gerontocracy: Genealogy and the Massachusetts Revolution’, National Genealogical Society Quarterly, LXVI (1978), 291-304.

- David Ader, Arthur Landry, and David Peete, in course papers written at Tufts University, 1979, have studied the Medford and Roxbury contingents in the continental army during the Revolution. In gemeal, young men who did not pay taxes comprised the rank-and-file of those who enlisted for more than a few days when the British were in the neighbourhood. See also B. Michael Zuckerman, ‘Neighbours Divided: The Social Impact of the Continental Army-Massachusetts, 1774-1786’, (Wesleyan University, A. B. honors thesis, 1971).

- For a detailed discussion of the residences and migration pattern of the prerogative faction, see Pencak and Crandall, ‘Metropolitan Boston’.

- John A. Schutz, ‘Those Who Became Tories: Town Loyalty and the Revolution in New England’, New England Historic Genealogical Register, CXXIX (1975), 94-105. For age of loyalists, see Pencak, ‘Revolt Against Gerontocracy’.

- Waldo died in 1759, Allen in 1754; for Pratt and Tyng see Shipton, Harvard Graduates, VI, 540-49; VII, 595-600.

- James Otis, The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved (Boston, 1764), 72.

- Quoted in Jack P. Greene, Colonies to Nation, 1763-1789 (New York, 1967), 34, 72.

- Edmund S. Morgan, ‘Thomas Hutchinson and the Stamp Act’, New England Quarterly XXI (1948), 488, 489; Hutchinson to William Bolian, 14 July 1760, Massachusetts Archives XXV, 14-17, pagination to typescript copy at the Massachusetts Historical Society prepared by Catherine Barton Mayo.

- Isaac Royall to Lord Dartmouth, 18 Jan. 1774, Ms. L., Massachusetts Historical Society.

- Thomas Hutchinson, History of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts Bay (Cambridge, 1936), III, 253.

- Lawrence Henry Gipson, ‘The American Revolution as an Aftermath of the Great War for Empire, 1754-1763’, Political Science Quarterly, LXV (1950), 86-104.