The British poster artist Cyril Kenneth Bird, known as Fougasse, once referred to posters as “anything stuck on a wall with the objective of persuading the passer-by”.

Introduction

The British poster artist Cyril Kenneth Bird, known as Fougasse, once referred to posters as “anything stuck on a wall with the objective of persuading the passer-by” (Stanley, 1983: 7). To persuade the passer-by appears to be the main function of the war poster, and it is not surprising that posters became a major medium of mass communication in the ‘cityscape’ of the UK during the First World War. It could be considered the broadest mobilisation of printed ephemera for political purposes in history, whereby many artists and designers were recruited to harness the power of persuasion both at war and on the home front. With all their efforts, they aimed to prove that whereas battles are won in battlefields, wars are won in the minds and hearts.

The war propaganda poster has been a matter of scholarly studies from a variety of perspectives, including visual arts, history, war and propaganda studies. However, textual representations have been given insufficient attention so far. This blog aims to rectify this neglect by examining several strategies of persuasion widely used in the First World War posters. Before doing so, I will briefly outline the main dominant topics which can be traced in posters produced in the UK during the Great War as well as the driving forces and purposes behind their production.

Popular Themes

Recruitment of Men to Join the Army

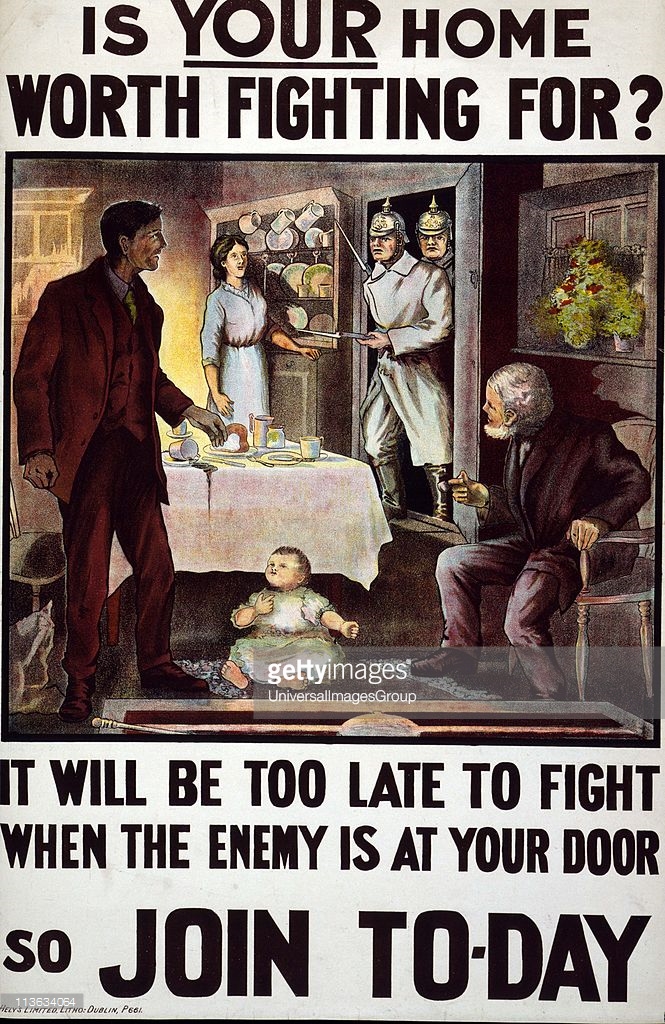

While the UK did not have conscription until 1916, the recruitment posters appealed to men’s sense of dignity and honour, and women were often given the role encouraging men to enlist and such were addressed to pressurise their men to do their patriotic duty for “King and Country”. These recurring themes were intrinsically linked with traditional family values where men acted as defenders of their families and homes. It was not uncommon when in the beginning posters sold the war as a matter of a better life choice by offering a deceptive image of war realities, but the initial enthusiasm was quick to give way to mobilisation efforts “by shame”.

Recruitment of Women to Enter the Workforce

Women were not expected to fight, but were supposed to become engaged in the Women’s Land Army, munitions factories and wartime charities in order to release more men to serve in the trenches. Such posters assigned unusual tasks for women thus challenging traditional gender roles.

Request for War Bonds and War Loans

The necessity of soliciting money provided an important topic for poster designers where money was often portrayed as an active force in military engagement.

Saving Resources and Reducing Consumption

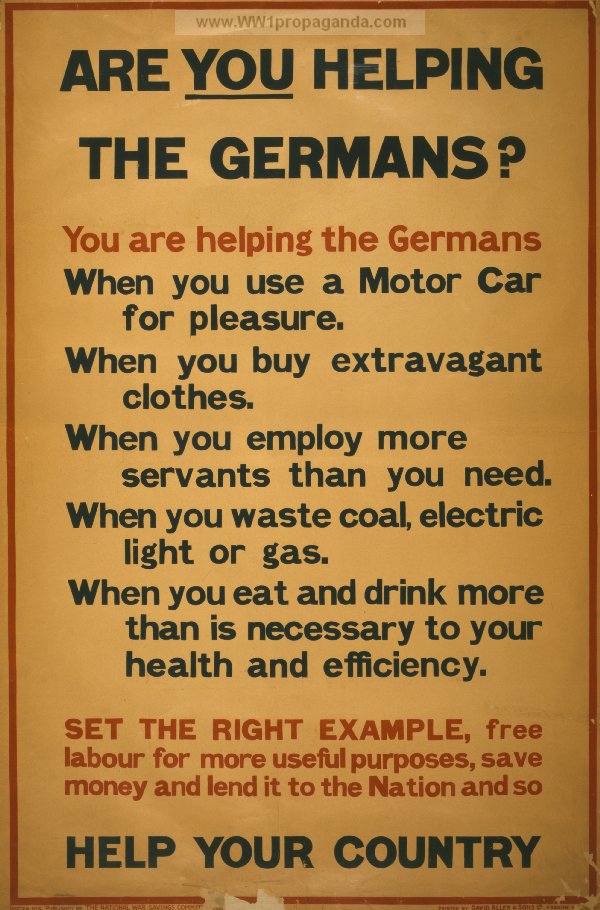

Posters were explicit in showing that excess consumption could help Germany, and reinforcing peer pressure was part of wider propaganda efforts.

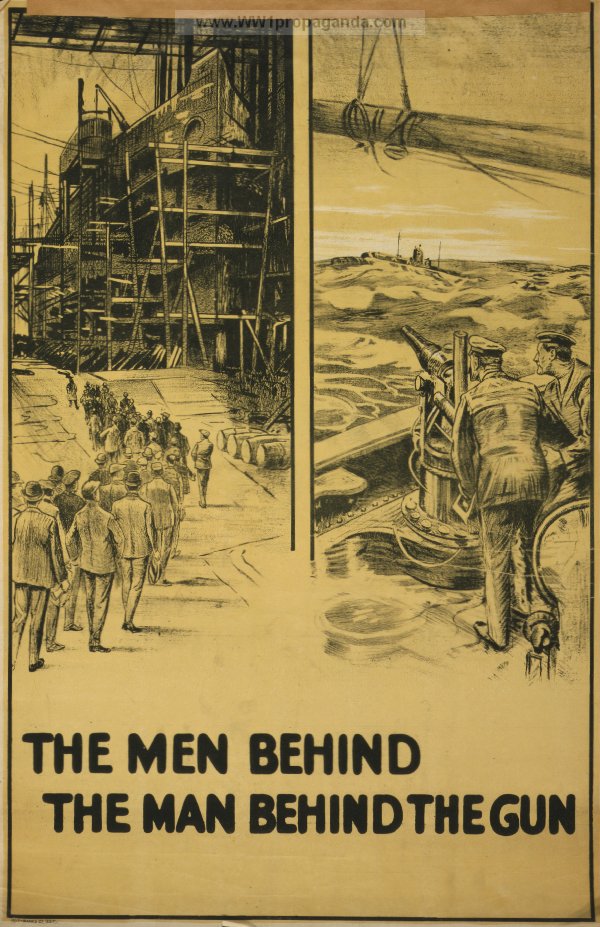

Increase in Productivity and Collective Efforts

Many posters were concerned with efforts to encourage industrial activity and increased productivity through collective effort. Skilled civilians were called upon to join the war efforts on the Home Front.

The persuasive power of these posters is expressed through various strategies of persuasion which include the following among others: dialogism, a them/us divide, locality/temporality and national symbolism. Below you can see examples of how such strategies are fleshed out in textual representations.

Strategies of Persuasion

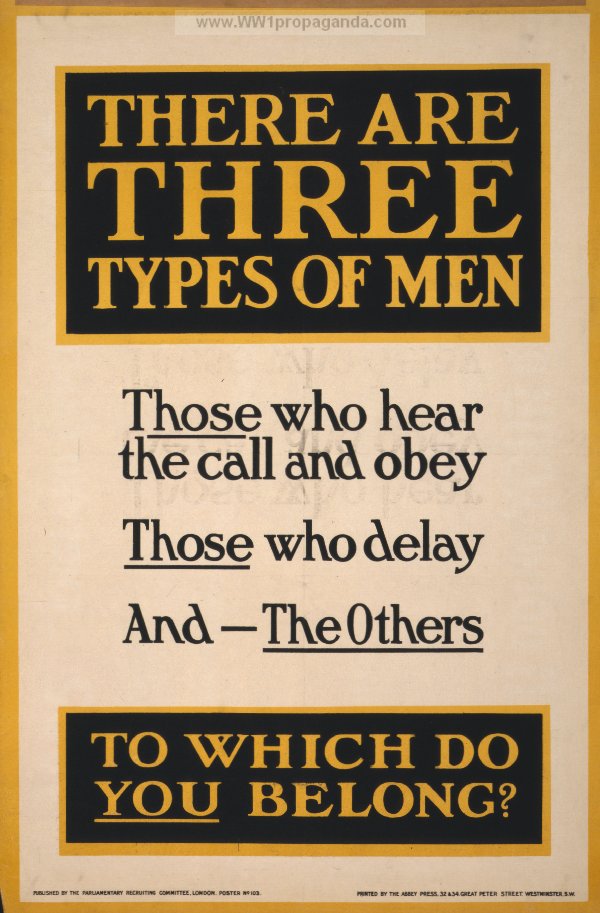

Dialogism

The effect of dialogue was created by the use of direct addresses to specific groups (footballers) and ethnicities (Jews), introduction of quotations (“Every player who represented England in rugby international matches last year has joined the colours” – extract from the Times) and the prolific use of personal and possessive pronouns (“you”, “yours”) as well as the imperatives (“Join the special Jewish unit”). The posters put the questions into the mind of the viewer (“There are three types of men… To which do you belong?”) to engender a response, and colloquial words (“Good bye, my lad”) and contracted forms (“can’t”; “there’s”) added a touch of lively conversation. Single men were usual targets, since under the Derby Scheme, married men were given the assurance that single men would be called upon first.

Them/Us Divide

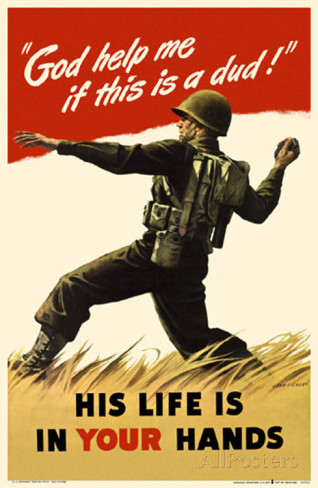

The war image of the enemy was demonised and remained of stylised simplicity (“German barbarians”), whereas the British side invoked God’s help and protection. The depiction of atrocities performed by Germans had to instil hatred and provoke action (“How the Hun hates! … British Soldiers! Look! Read! And Remember!”), and references to God (“God help me”) helped to justify actions of the Allies.

Locality and Temporality

For the First World War posters, as for any other piece of war persuasive propaganda, it was important to anchor the moment in space and time by calling for action right here, right now. The posters made extensive use of temporal markers (“now”, “to-day”, “at once”) and referred to different periods in the past (1805; Nelson’s words “England expects”), present (“It is far better to face the bullets…Join the Army at once”) and future (“It will be too late to fight”) to reinforce the message. The geographical locations (“Free trip to Europe”) were supposed to give a sense of direction and purpose to fight for Britain and neighbouring countries.

Emotional Appeals

In addition to vivid imagery, emotionally loaded words had the objective of embedding a broad spectrum of feelings ranging from happiness and courage to fear and guilt. The employment of comparative and superlative adjectives (“it is far better”, “the grimmest menace”) alongside the inverted order of words (“together we win”) made the message more emphatic and channelled emotions in a particular direction for urging action. The imperative addresses (“Men of Britain!”) with metaphors (“sword of justice”) and allusions to war-related (the sinking of Lusitania) served the same purpose.

National Symbolism

The posters were abundant in national symbols and allegorical figures, such as John Bull as a personification of Britain and Tommy Atkins as an archetypical figure for the British soldier. The artists relied on symbolism to illustrate their points of nationhood, such as in posters below presenting Britain as the Old Lion with the young lions as the Empire nations, and England as St George fighting the dragon.

The above illustrated linguistic repertoire for strategic persuasion in posters is extensive but definitely not exhaustive. However, as can be seen even from this concise overview, posters were designed with the purpose of being an essential weapon in the national arsenal of warfare. The public was constantly bombarded with war-related messages of such posters which served as a mirror of life – both reflecting and distorting the reality. Given that the poster was one of the most popular types of mass media, it seems only natural to suggest that the First World War gave rise to the Great War of Words and Images. Although the role of the poster is now obviously limited due to today’s vibrant ‘media-scape’, strategies of persuasive communication are just as much a part of our contemporary world with its information wars as they used to be in those days.

Originally published by the World War I Centenary under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England and Wales license.