While the price of milk dropped, dairy products such as ice cream remained expensive.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In October 1921, a cow mysteriously appeared in the grassy House Office Building courtyard. Bossie arrived amid milkshake profiteering, sundae protests, and illegal ice cream on the Capitol grounds. Cold and creamy on a summer evening, ice cream seems like the most innocent of sweets. But it once got pretty sticky around the House.

Soda fountain milkshakes and drugstore banana splits were important rituals for children on summer vacation and couples sharing a first date in the early 20th century. When ice cream prices rose during World War I, people scrimped and saved to enjoy their root beer floats. After the war, dairy farmers lowered their prices so that milk by itself was once again economical. Photographers snapped Martin Barnaby Madden and other Representatives drinking milk at lunchtime to illustrate congressional thriftiness.

‘Children Thrive’

While the price of milk dropped, dairy products such as ice cream remained expensive. Around the country, the cost of a soda fountain treat stayed just as high as wartime. Someone was profiting, but it wasn’t the dairy farmer.

In 1921, Congress began looking into the prices of food and dairy products through the Joint Commission of Agricultural Inquiry. “There has been a marked revolution in the dairy industry in recent years,” the commission reported. Its findings filled four volumes, nearly 1,000 pages. Meanwhile, public anger at soda shop owners and drugstore “ice cream profiteers” swelled.

“Children thrive on an ice cream diet, and it is unfair to keep them from getting it,” wrote the Trenton Evening Times. “Ice cream is a popular and beneficial article of food, especially in warm weather, and high prices should not be allowed to interfere with its generous consumption.” Ice cream looked like a health food and tasted great. Keeping children from their ice cream sodas was a protest-worthy offense. Newspapers reported that adults boycotted sellers as thousands of children “paraded, sloganed and petitioned for these frozen dainties at old time prices.”

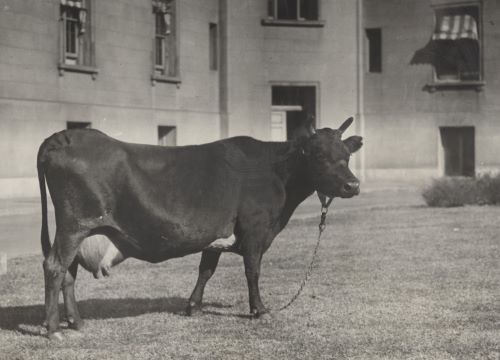

That October, one protester took a less conventional route. As a House Collection photograph shows, someone planted a sleek, black dairy cow inside the House Office Building during the Joint Commission’s investigation. “Having heard a certain distinguished member of the House of Representatives, a member of the milk investigation committee, declare bitterly that the only way to beat the milk profiteers was buy a cow,” the photo caption explained, “‘Bossie’ arrived at the House Office Building yesterday in search of a congressman owner.” Peacefully grazing in the trapezoidal central courtyard of what is now known as the Cannon Building, Bossie appeared unconcerned with congressional investigations into banana split swindling.

The ‘Milk Profiteers’

Had any Members of Congress actually attempted to “beat the milk profiteers” by milking the cow and churning their own ice cream in the courtyard, they would likely have broken the law. In March 1921, Congress established standards for food weight and measurement in the District of Columbia. According to the law, milk or cream products could only be sold in authorized units, which included the gallon, pint, half-pint, and the more-obscure quantity “one gill when filled to the bottom of the cap seat, stopple, or other designating mark.”

Ice cream scoops could only be sold by the cup or gill (approximately a half-cup). According to city officials, the sale of ice cream cones in unauthorized sizes was the “the largest single criminal activity” in the District of Columbia. The New York Times reported that ice cream pops were “sold in the shadow of the Capitol in brazen defiance” of the law. In the 1920s, chocolate malt profiteering, milkshake protests, and illegal single scoops sprinkled the story of ice cream at the Capitol. A cow in the House Office Building was just the cherry on top.

Bibliography

- Kendra Smith-Howard, Pure and Modern Milk: An Environmental History since 1900 (Oxford University Press, 2014)

- New York Times, October 15, 1963

- Trenton Evening Times, July 31, 1921

- Woodbury Daily Times, July 28, 1921; 41 Stat. 1217.

Originally published by the Office of the Historian, United States House of Representatives, 06.29.2015, to the public domain.