Pasteurization’s success is so complete that it often becomes invisible, a background technology of safety like chlorination and vaccination.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

The Lethal Glass: Milk Before Pasteurization

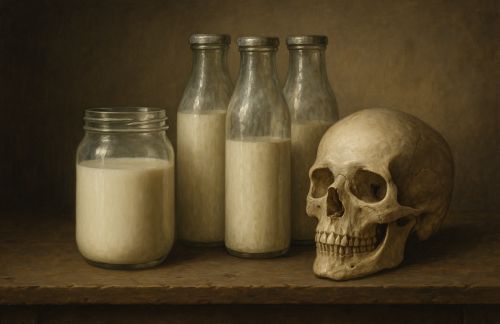

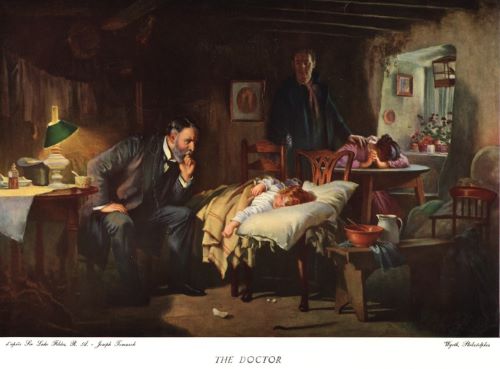

In the crowded cities of the nineteenth century, milk was both cherished and deadly. It carried tuberculosis, typhoid, diphtheria, and scarlet fever into nurseries and tenements, often with no outward sign of corruption until it was too late.1 Urban dairies fed cows distillery refuse, transport chains stretched without refrigeration, and adulteration with contaminated water hid behind the liquid’s innocent color.2 Infant funerals spiked in summer, when heat hastened spoilage and physicians still lacked a common microbial language for what they were seeing.3

The Science of Spoilage and Germ Theory

The microscope reoriented the conversation. What reformers had called “white poison” took on definition once milk was recognized as a superb growth medium for bacteria, its proteins and sugars nurturing organisms that thrived in warm pails and lukewarm kitchens.4

Epidemics traced to raw milk began to appear in official reports. Typhoid clusters were linked to single farms and delivery routes; diphtheria traveled with the morning round. As case investigations accumulated, public trust in laboratory diagnosis rose alongside the new discipline of bacteriology.5

Yet practice lagged behind knowledge. Home boiling was urged, but milk that had already been contaminated upstream could arrive with enough microbial load to overwhelm household precautions. The problem was systemic, and so would the remedy need to be.

Pasteur’s Intervention

Louis Pasteur’s work on wine and beer in the 1860s offered that remedy in principle. By heating liquids to controlled temperatures and cooling them promptly, he showed that spoilage organisms could be inactivated without ruining taste.6 Applied to milk, the method promised a way to preserve nourishment while neutralizing invisible threats, translating germ theory into an everyday public safeguard.

From Experiment to Ordinance

Adoption was halting. Many producers insisted that cleanliness at the source was sufficient and that heating was an expensive concession to urban queasiness. Consumers, too, worried that heat would strip milk of its vitality. The bridge between lab bench and table glass was built not by rhetoric but by demonstration: philanthropic pasteurization stations, notably those supported by Nathan Straus in New York, coupled cheap, heated milk with meticulous record keeping, and infant deaths declined.7

Municipal politics followed evidence. Chicago’s 1908 mandate for pasteurization became a bellwether, its ordinance grounded in morbidity data and the persuasive arithmetic of lives saved.8 Legal challenges cast the new rules as an affront to economic liberty, yet courts were increasingly willing to privilege health over custom, particularly as pure milk campaigns exposed swill scandals and adulteration schemes.9 By the 1930s, a regulatory package of pasteurization, veterinary inspection, and bacteriological standards had taken hold in most large cities, and the term “milk-borne disease” receded from headlines.10

The Midcentury Decline of Milk-Borne Disease

Statistics tell the aftermath. Urban pasteurization correlated with steep drops in infant diarrheal mortality and with the practical elimination of bovine tuberculosis from city milk supplies.11 The transformation was cultural as well as microbial: the daily glass of milk, once a wager, became a ritual of reassurance, folded into school lunches and public nutrition programs.

Legacy, Memory, and the Raw-Milk Revival

Pasteurization’s success is so complete that it often becomes invisible, a background technology of safety like chlorination and vaccination. That very invisibility feeds periodic revivals of raw-milk romanticism, which tout taste and tradition while downplaying recurrent outbreaks of Campylobacter, E. coli, and Listeria traced to unpasteurized products.12

The longer arc is instructive. It was never a single discovery that secured safe milk, but the slow stitching together of laboratory insight, municipal governance, and public persuasion. Pasteur’s method supplied the hinge between worlds. Reformers supplied the pressure. Households supplied the trust.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Deborah Blum, The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century (New York: Penguin Press, 2018), 212–215.

- E. Melanie DuPuis, Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink (New York: New York University Press, 2002), 58–61.

- Richard A. Meckel, Save the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850–1929 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), 178–183.

- Deborah Valenze, Milk: A Local and Global History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 154–156.

- E.C. Garthe, “The Pasteurization of Milk,” American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health 33:7 (2011): 896-897.

- Louis Pasteur, Études sur le vin (Paris: Imprimerie Impériale, 1866), 85–97.

- Meckel, Save the Babies, 192–199.

- DuPuis, Nature’s Perfect Food, 110–113.

- James Harvey Young, Pure Food: Securing the Federal Food and Drugs Act of 1906 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 140–147.

- U.S. Public Health Service, “Pasteurized Milk Ordinance,” Public Health Bulletin no. 220 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935), 4–9.

- U.S. Public Health Service, “Milk and Milk Products,” 10–14.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Outbreak of Salmonella Typhimurium Infections Linked to Commercially Distributed Raw Milk,” MMWR 74:27 (2025): 433-438.

Bibliography

- Blum, Deborah. The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. New York: Penguin Press, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Outbreak of Salmonella Typhimurium Infections Linked to Commercially Distributed Raw Milk.” MMWR 74:27 (2025): 433-438.

- DuPuis, E. Melanie. Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink. New York: New York University Press, 2002.

- Garthe, E.C. “The Pasteurization of Milk.” American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health 33:7 (2011)

- Meckel, Richard A. Save the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850–1929. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990.

- Pasteur, Louis. Études sur le vin. Paris: Imprimerie Impériale, 1866.

- U.S. Public Health Service. “Pasteurized Milk Ordinance.” Public Health Bulletin no. 220. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935.

- Valenze, Deborah. Milk: A Local and Global History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

- Young, James Harvey. Pure Food: Securing the Federal Food and Drugs Act of 1906. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.14.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.