Periodic outbursts of hostility incited numerous massacres of the Jews in the Middle Ages.

By Dr. Sara M. Butler

Professor and King George III Chair in British History

The Ohio State University

Setting the Scene

The period leading up to the expulsion of the Jews from England in July of 1290 was a time of mounting uncertainty for the Anglo Jewry. That Saint Augustine’s long-endorsed “toleration theory”[1] was beginning to lose its force is evidenced by the proliferation of ritual murder charges, beginning with the homicide of “Saint” William of Norwich in 1144 and including at least seven other supposed murders of Christian children since that time.[2]

Periodic outbursts of hostility incited numerous massacres of the Jews. In 1190, a wave of antisemitism ignited by King Richard’s departure on crusade, led to the slaughter of the entire Jewish population of the city of York, roughly 150 individuals. Violence intensified in the 1260s under the rabble-rousing of England’s baronial rebel, Simon de Montfort, whose vehement antisemitism seems to have been tied to his family’s various debts to French Jewish money-lenders. Simon de Montfort has been linked to both riots against London’s Jews in 1262 as well as the 1265 massacre that resulted in the deaths of 400 London Jews, and sparked pogroms in multiple other English cities, such as Canterbury and Worcester.[3]

Antisemitism found its voice also in legislation that increasingly restricted Jewish status and rights. In 1253, King Henry III issued the first Statute of Jewry, which affirmed that only Jews who served the king, in one form or another, were permitted to remain in England. Among other restrictions it imposed, we discover: an order to speak in hushed tones (submissa voce) in synagogue so that Christians did not have to hear them pray; bans on Christian wet-nurses suckling Jewish children, buying or selling meat during Lent, the construction of any new synagogues, as well as any “secret familiarity” (secretam familiaritatem) between Christians and Jews. It also restated (but this time with force) the 1218 obligation that Jews identify themselves publicly through the wearing of a badge openly displayed on the chest.[4]

In England, the “badge of shame” represented the twin tablets of the Ten Commandments. Marginal illustration from the Rochester Chronicle (British Library, Cotton Nero D. II), fol. 183v. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The year 1275 marks Edward I’s Statute of Jewry, described by Paul Brand as “the most wide-ranging, the most detailed and the most radical of

all the legislation of the thirteenth century concerned with the Jewish community.”[5] Notably, it prohibited Jews from charging interest on loans. This point was critical to the well-being of the Jewish community. Even though only about 1/100th of England’s Jewish population was actually involved in money lending, it was a major source of income for the community, and one of the only reasons Jews were tolerated in the kingdom.[6] The statute also codified the Jew’s status as the king’s serf, a concept borrowed from contemporary French and German law and intended to concretize their separate status as indenture not privilege.[7]

From that point onward, conditions rapidly deteriorated. The years 1278 and 1279, for example, saw England’s Jews embroiled in a coin clipping scandal, leading to the public execution of another 269 Jews.[8] Yet it was Edward I’s escalating debts, fueled by his military campaigns with the futile goal of reuniting Arthur’s legendary empire, that built the foundation for England’s expulsion of the Jews in 1290. Until Oliver Cromwell extended an invitation to return in 1655, Jews were a rare sight in the English landscape.

The Case: Homicide, Spite, and “Abominable Mixing”

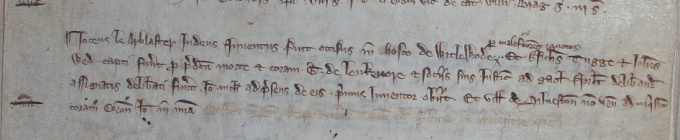

C 144/13, m. 6/2. An inquest de odio et atya. Drawn from Chancery: Criminal Inquisitions. Courtesy of The National Archives, Kew, Surrey. / Photo by Sara Butler

Against this backdrop, let us consider an inquest into allegations surrounding the homicide of Josce le Arblaster, Jew of Northampton, in the third year of the reign of King Edward I (1274/75). Olympias of Towcester, a Christian woman,[9] stood accused of the crime. Josce’s daughter, known only in the records as Floria the Jew, had come forward to lodge a formal accusation (known in medieval parlance as an “appeal”) against her. Olympias emphatically denied that she was in any way liable for Josce’s death. Indeed, she maintained that she was a victim to Floria’s malevolent plotting, accused out of hate and spite (de odio et atya) for a crime she did not commit. Nonetheless, Olympias had been arrested and imprisoned at Northampton while awaiting trial.

Taking advantage of the growing popularity of the writ de odio et atya, Olympias pleaded an exception, and asserted her right to have the claim of hate and spite examined by a verdict of the country (that is, a jury trial). A writ issued from chancery ordering the county sheriff to assemble a jury to look into the question of whether Olympias was in fact being maliciously prosecuted. The jurors assigned to investigate the credibility of Olympias’s statement were not only all male (as one would expect of a medieval jury), they were also all Christian.[10] This, too, was not unusual. Mixed juries of Jews and Christians were assigned only when the defendant was Jewish. Thus, even though the inter-religious nature of the crime in this situation might seem to benefit from bipartisan analysis, the law’s first priority was to protect the defendant’s right to judgment by a jury of his peers.

The jury found in Olympias’s favor. They declared that she was not culpable, that she had been appealed out of hate and spite chiefly because the circumstances cast a negative light on the defendant, whose home doubled as the scene of the crime. The day of the murder, Josce breakfasted (gentaculavit) at Olympias’s home. The jurors skirted around the issue of why Josce was present in Olympias’s domicile at such an early hour. One cannot help but speculate whether the “abominable mixing” which seems to have kept Pope Innocent III up at night dreaming of ways to prevent inter-religious coitus, may have been to blame.[11] Apparently, discord broke out between Josce and Olympias before they had even finished their breakfast. Josce then withdrew, and was immediately killed, although the record does not disclose the identities of the perpetrators. When she learned the news of their quarrel, Floria presumed the worst, and appealed Olympias before authorities.[12] The jury’s finding was compelling: a notation in the close rolls for October 22 of 1275 explains that the king had sent a letter to the sheriff commanding Olympias’s release from prison.[13]

The jury’s account, however, does not tell the whole story. The close rolls add that John Whed of Claxkesthorpe was also being held for the homicide of Josce le Arblaster, for which he had been appealed (although the notation does not say by whom); he, too, was to be released by order of the king.[14] Had Floria also accused John Whed, and if so why? How does he fit into the story?

The eyre rolls supply a few more pertinent details. We discover that Josce’s corpse was found in Whittlewood Forest, just east of Silverstone, slain by what historians have come to recognize as the ubiquitous scapegoat, the utterly fictitious “unknown malefactors.” Along with a man named Nicholas Tugge, John Whed (here, “John Wet of Clapthorn”) was arrested for Josce’s murder. There is no mention of who accused them, or the basis of that accusation. However, in light of the discovery of the unknown malefactors, it comes as no surprise that Geoffrey de Leukenore and his fellow justices of gaol delivery acquitted the two defendants, even without the testimony of the unnamed first finder who had reportedly died in the intervening time.[15]

The scattered and fragmentary nature of the information makes connecting the dots in this case a trial. To add the final twist: a memorandum from the following year regarding Josce’s postmortem inquisition brings Josce’s widow into the spotlight, and as you might be able to guess, her name was not Olympias, but Ivetta.[16] At the very least, this court record delivers context to Floria’s “malicious” appeal. Clearly, Floria’s accusation was not prompted because her widower father’s Christian girlfriend had embarrassed him (and Floria) with a public quarrel. Instead, Olympias was the Christian mistress stealing the affection (and who knows what else) that rightfully belonged to Floria’s Jewish mother, humiliating the entire family, and causing a public scandal.

So: did John Whed and Nicholas Tugge murder Josce because his affair with Olympias had become notorious and locals were unwilling to tolerate a Jewish man sleeping around with Christian women? Was Olympias involved in the murder at all? Or, was her appeal simply malicious, as she had argued from the very beginning?

The Victim

A medieval crossbow. From Jean Froissart’s Chronicles (BNF, FR 2643), fol. 165v. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Who was Josce le Arblaster and why does his murder matter? When Josce died, goods and chattels worth seven marks came into his wife’s hands, with an additional forty shillings into his son’s, revealing that Josce was an affluent man.[17] His personal fortune presumably derived from his business. His occupational by-name, “Arblaster,” means “crossbowman”; in this instance, it seems likely that Josce fashioned crossbows, rather than shot them. This was a highly respected and well remunerated profession, especially at a time when England was involved in war on multiple fronts.

That Josce was also influential in Northampton’s Jewish community is hinted at by the fact that he once stood surety to Benedict son of Isaac the Jew of Northampton in a homicide appeal against a Christian named Thomas son of Richard Edymarr, whom he accused of slaying his father. Benedict failed to appear in court to pursue his appeal, although it is not clear whether intimidation or uncertainty accounted for his absence. As a result, he and his sureties, Josce le Arblaster and David le Taillur, were “in mercy” (meaning, they forfeited the pledges they had promised in order to guarantee Benedict’s court appearance). Thomas was acquitted.[18] Sureties were chosen typically because they had money, and were law-worthy (that is, widely respected), implying that Josce also fell into this category.

Because Josce was a man of some importance, his murder as well as the blatant mismanagement of his homicide investigation, take on greater significance. Typically, property and position were all that was required to protect a person against victimization in the medieval period. And yet, in Josce’s situation, multiple juries and the king’s own men colluded to allow a homicide motivated by hatred of the Jews to go unpunished. Josce’s death offers valuable insight into persecution as it was experienced on an individual basis. His death is not enumerated as one of the victims of England’s medieval pogroms; yet, it clearly belongs to the category of hate crimes.

Josce’s Daughter: The Hero of the Story?

In many respects, what is most interesting about this case is Floria’s appeal. Quite simply, it should not exist. Even if Floria had been a Christian, her accusation violated the limiting rule which restricted a woman’s right of appeal in felony accusations to two instances: 1) a physical assault upon her person (usually in the case of rape, or abortion by assault), or 2) the homicide of her husband, with some provision that he had died in her arms and thus she was an eyewitness to the attack.

Admittedly, women’s penchant for appealing in thirteenth-century England seems to have often led them to stray beyond these legal boundaries, issuing appeals in the deaths of sons, fathers, brothers, and others. Judges did sometimes quash those appeals on the grounds that women had no right to make them; however, Patricia Orr explains that they usually did so only when the appeal had no merits and was destined for failure anyways. The king’s justices permitted those appeals with merit to proceed, even though they originated with a woman, in the interest of seeing justice done.[19]

Yet, all of this was relevant to a Christian woman’s right of appeal. Floria was Jewish. How was a Jewish woman able to appeal unlawfully (and perhaps even maliciously?) a Christian woman? The postmortem inquisition also indicates that Floria had a brother named Ben: shouldn’t it have been Ben’s responsibility to pursue his father’s killers? Even Ivetta had a better claim to an appeal.

Jewish women’s appeals against Christians were extremely rare. In her meticulous survey of crime and Jews in the years leading up to the English expulsion, Zefira Rokéah unearthed only two other examples:[20]

- In 1283, Reymota widow of David son of Meyr the Jew sued Alan le Charretter, Walter of Newark, and Henry of Doddington for assault. Purportedly, they beat her, gave her blows, and broke the king’s peace. Alan was not arrested because authorities could not locate him. Walter and Henry did appear in court, and were acquitted by the jury. Reymota abandoned her appeal, failing to appear in court; and thus, (as was usual when an appellor nonsuited), an order went out for her arrest.[21]

- In 1287, Saphiret widow of Moses of Kent appealed Mabilia la Noyare of the death of her daughter, Bassa. Once again, Saphiret violated the limiting rule: however, her status as widow may have made the difference. With Bassa’s father out of the picture, who else from the family might be responsible for prosecuting her murderers? Saphiret also abandoned her appeal, and was ordered arrested. The jury declared that Mabilia was not a suspect after all, and so even though she had fled the scene of the crime (commonly interpreted as a sign of guilt), she was invited to return.[22]

With Floria, we have a trio of Jewish women who all had the courage to stand up to Christian aggressors in a time of deepening antipathy. The fact that two of these women appealed in violation of the limiting rule implies that local authorities sympathized enough with their cause to allow their appeals to go forward. In the end, all three failed. It seems likely that intimidation prompted Reymota and Saphiret to abandon their appeals. Thus, despite being victims themselves, they were punished more harshly than those they accused. Both were arrested, and then fined before being released. Why didn’t Floria endure the same fate? Did Olympias turn to an inquiry of hate and spite because Floria refused to be intimidated?

What is perhaps most fascinating in all of this, is Floria’s behavior. In all likelihood, her father was murdered for his relationship with a Christian woman. Did this cow her? Not at all. When both her brother and mother failed to do anything, she stepped in to see justice done. Floria also seems to have been operating on the assumption that she had the same rights (both official and unofficial) as a Christian woman; and somehow, despite the rising level of hostilities, no one was prepared to correct her.

Not that long ago, Barrie Dobson complained that despite the flurry of writing on the subject of women’s history since the 1970s, “the Jewish wife, widow, and daughter of medieval England still linger in comparative obscurity.”[23] Maybe we should start with women like Floria.

Notes

- Toleration theory: in which Saint Augustine argued that because Jews are to be witnesses to Christ’s return at the end of days, they must not be slaughtered or forced into conversion, but tolerated. For an interesting discussion of Saint Augustine’s views on the Jews, see Paula Frederiksen, Augustine and the Jews: A Christian Defense of Jews and Judaism (Yale University Press, 2010).

- On ritual murder, see: E.M. Rose, The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe (Oxford University Press, 2015), and Geraldine Heng, “England’s Dead Boys: Telling Tales of Christian-Jewish Relations before and after the First European Expulsion of the Jews,” Modern Language Notes 127, no. 5 (2012): S54-S85.

- Joe Hillaby, “London: The 13th-century Jewry Revisited,” Jewish Historical Studies 32 (1990-1992), 136.

- The statute of the Jewry is documented in the Calendar of Close Rolls for the years 1251-53, pages 312-13.

- Paul Brand, “Jews and the Law in England, 1275-90,” The English Historical Review 115, no. 464 (2000), 1140.

- Colin Richmond, “Englishness and medieval Anglo-Jewry,” in The Jewish Heritage in British History: Englishness and Jewishness, ed. Tony Kushner (Frank Cass, 1992), 53.

- Brand, “Jews and the Law,” 1142.

- Hillaby, “London,” 126.

- The name “Olympias” appears under the heading “Latin Christian names” in Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records (Phillimore & Co. Ltd, 1892), 462.

- Or, so the names would seem to suggest: William de Turnill; Hugh of Missenden, knight; Ralph le Gras; William Russel of Plumpton; William son of Alexander de Blacolvesl (Blakesley?); Geoffrey de Ipre de Wytheburn; Geoffrey le Salter of Towcester; Roger de Plore; Walter Brieyich of Atteneston; William Deynte of the same; Robert Huberd, and Thomas le Fouere of the same.

- Canon 68 of Lateran IV was Pope Innocent III’s solution. It required Jews to don identifiers on their clothing to mark their separateness.

- The National Archives, Kew, Surry (hereafter, TNA) C 144/13, m. 6/2.

- CCR for Edw. I, vol. 1: 1272-1279, pp. 212-215. In the calendar, she is described as Olympias de Goncestria; for those familiar with English paleography, it is easy to see how “Toucestria” could easily be read as “Goncestria”.

- Ibid.

- TNA JUST 1/623, m. 7d and 24d.

- Calendar of the Plea Rolls of the Exchequer of the Jews, ed. Hilary Jenkinson (Colchester, 1929), vol. 3, 109.

- Ibid.

- TNA JUST 1/623, m. 24.

- Patricia R. Orr, “Non Potest Appellum Facere: Criminal Charges Women could not – but did – bring in Thirteenth-century English Royal Courts of Justice,” in The Final Argument: The Imprint of Violence on Society in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Donald J. Kagay and L.J. Andrew Villalon (Boydell, 1998), 141-62.

- Zefira Entin Rokéah, “Crime and Jews in Late Thirteenth-Century England: Some Cases and Comments,” Hebrew Union College Annual 55 (1984), 95-157.

- TNA JUST 1/486, m. 34; see Rokéah, “Crime and Jews,” 134.

- TNA JUST 1/278, m. 73; see Rokéah, “Crime and Jews,” 130.

- Barrie Dobson, “The Role of Jewish Women in Medieval England,” in his The Jewish Communities of Medieval England: The Collected Essays of R.B. Dobson (Borthwick Publications, 2010), 127.

Originally published by Legal History Miscellany, 08.17.2018, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.