They had more rights than women in contemporary cultures to the east and west of Mongolia, some even reigning as regents.

By Mark Cartwright

Historian

Introduction

Women in the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE) shared the daily chores and hardships of steppe life with men and were largely responsible for tending animals, setting up camps, childrearing, producing food and cooking it. Having rather more rights than in contemporary cultures to the east and west of Mongolia, women could own and inherit property, were involved in religious ceremonies and could be shamans, and the wives of senior tribal leaders could voice their opinions at tribal meetings. Several Mongol women, the widows or mothers of Great Khans, even reigned as regents in the period before a new khan was elected as ruler of the Mongol Empire, often a span of several years.

Setting up Camp

As the Mongols were a nomadic people, everyone – men, women, and young children – had to be able to ride well and use a bow for hunting. In the same vein, men and women were usually capable of doing each other’s tasks since if one died, the survivor in the partnership had to carry on and look after the family and its herds. Women were responsible for both setting up and packing up camps, putting the yurt tents and the family’s belongings onto the carts, which they usually drove, and packing any pack animals like horses and camels.

There was a dedicated space within the yurt for men and women, the former having the west side and the latter the east side where the cooking was done (easily defined since the doorway was traditionally made to face the south). The positioning of the yurts themselves in a camp (ordu) was important in imperial and larger camps with the senior wife having the tent nearest to the west, the most junior wife to the east, and the concubines, children, and servants someway behind.

As experienced camp masters, women were an important element of the logistics so vital to Mongol warfare with its fast, light cavalry units. They followed behind the main forces with the much slower wagon trains of supplies and horses, when often a single woman drove a train of several connected wagons.

Daily Chores

Mongol women tended animals, collected food, cooked and processed it while men hunted. Women made cheese, butter, and dried the milk curds, and also had to look after the herds while the men were away hunting which could be several weeks at a time. Women milked the sheep, goats, and cows while only men milked mares and produced the alcoholic beverages that were so popular. Women were involved in the laborious churning of milk in large leather bags using a wooden paddle, a process that took several hours and eventually made the mildly alcoholic kumis drink still drunk today. At least women could also enjoy the fruit of their labours as drinking to excess by both men and women seems to have been a social norm without any stigma attached to it (even having a certain honour). Neither were women excluded from the rare feasts when nomads got together in one place such as a meeting of tribal chiefs to elect a new leader or to celebrate important birthdays, weddings and so on.

Marriage and Family

Traditionally, Mongol marriages had the aim of cementing clan relationships and strengthening alliances. Indeed, it was the custom to marry outside one’s clan group (exogamy) and there was a custom of abducting women from rival tribes as a means to strengthen one clan group and weaken the other. Most marriages, though, would have been designed to reinforce existing bonds between family groups.

Men paid a bride price to their future father-in-law or offered labour as an alternative. As many nomadic men were relatively poor, it was a common custom merely to steal a wife during a raid, never mind any political benefits. In more genteel pre-arranged marriages, the future bride typically brought with her a dowry consisting of such valuables as livestock, jewellery, cloth, servants, and possibly slaves. The dowry might be ‘paid’ over several years and was usually lower in value than the bride price paid by the groom and his family. The dowry remained the property of the wife and was divided, on her death, amongst her children. In the ever-practical life of the nomads, sometimes a double marriage might be arranged between two family groups, each one providing a groom and bride and so the necessity of a bride price from each was avoided. Wives received a small portion of their husband’s property, which they managed but then handed on to the youngest son after his father’s death.

Women looked after the children and seem to have played an active role in family-decision making, with such sources as the 13th-century CE The Secret History of the Mongols mentioning the wives of rulers making speeches to enthuse warriors and promote loyalty to their husbands. One way to promote loyalty was hospitality – entertaining the husband’s family, allies, and any visitors – and this was the responsibility of the wife. If a husband predeceased his wife, she might be ‘adopted’ by a junior male relative of his. According to Mongol laws, women could divorce and own their own property but just how often this was the case in practice is not known. In cases of adultery, both the man and woman were executed.

Mongol society was patrilineal, and polygamy was common amongst those men who could afford multiple wives and concubines. However, one wife was always selected as senior, and it was her children who would inherit their father’s property and/or position within the tribe. As the youngest son usually inherited the family property, he and his wife would typically live with his parents. Senior wives of tribal leaders who became widows often still represented their late husband at tribal gatherings such as the kurultai which decided future rulers.

Clothing

Mongol women made felt by pounding sheep’s wool. They also made material from animal skins and prepared leather. Cloth and clothing were one of the important assets of a family and were often given as gifts and as part of a bride’s dowry. Men’s and women’s clothing was very similar, with both sexes wearing silk or cotton undergarments, trousers, thick felt or leather boots, and a conical hat made from felt and fur with flaps for the ears and an upturned brim at the front.

The most recognisable piece of outer clothing, still widely worn today, was the short robe or deel. This one-piece long jacket was folded over and closed on the left side of the chest (left breast doubled over the right) with a button or tie positioned just below the right armpit. Some deel had pockets and the sleeves typically went only down to the elbow. The outer lining of the robe was of cotton or silk and heavier versions had an additional fur or felt lining or a quilt padding. The inner lining was typically turned over a little to the outside of the garment at the sleeves and hem. For those who could afford it, the robe might have some exotic fur trim at the collar and edges. A wide leather belt decorated with metal additions was worn, with women’s versions being the more decorative. In winter a heavy coat of fur or felt was worn over the deel robe.

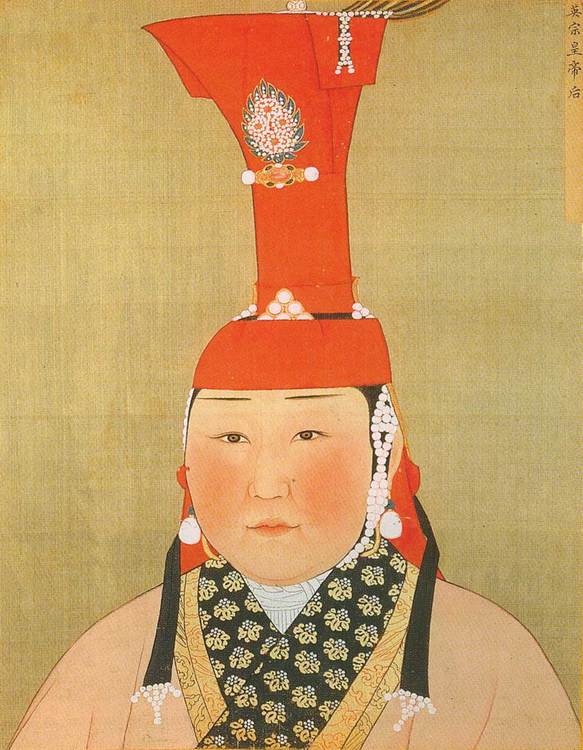

Elite men and women distinguished themselves by sporting a few peacock feathers in their hats. One of the few areas where women differentiated themselves from men, and then only elite women, was the elaborate boqta headdress which had pearls and feathers decoration. One can still see these headdresses today when, for example, Kazakh women attend traditional festivities. While both men and women wore earrings, women also added metal, pearl, and feather decorations to their hair.

Religion

The religion practised by the Mongols included elements of shamanism and shamans could be both men (bo’e) or women (iduqan). Robes worn by shamans often carried symbols such as a drum and hobby horse, representing the guardian and protector spirit of the Mongol people. Shamans were believed capable of reading signs such as the cracks in sheep’s shoulder bones, allowing them to divine future events. An ability to alter the weather was another shaman skill, particularly as a bringer of rain to the often arid steppe. Shamans could help with medical problems and return a troubled spirit back to its rightful body. Women participated in other religions practised within the empire such as Taoism, Tibetan Buddhism, and Islam, sometimes even presiding over services. Imperial women could also be generous patrons of certain religions and their institutions.

Famous Mongol Women

Alan Goa

Alan Goa (aka Alan-qo’a) was the mythical mother of the Mongol peoples who was said to have taught her five sons that in order to thrive they must always stick together and support each other. To get this message across, she gave them a lesson in unity known as the Parable of the Arrows. Alan Goa gave each son an arrow and told him to break it; each son did so easily. She then presented a bundle of five arrows and not one son could break them. Sadly, the descendants of Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 CE) would not remember this story when they broke up the Mongol Empire into various independent khanates.

Hoelun

Hoelun (aka Hoelun-Eke or Hoelun-Ujin) was the mother of Genghis Khan who fled with her son into the steppe wilderness after her husband, the tribal leader Yisugei, was poisoned by a rival. Genghis, then called Temujin, was still only nine or twelve years old at the time and so he could not maintain the loyalty of his father’s followers. As a consequence, he and his mother were abandoned on the Asian steppe, left to die. However, the outcast family managed to forage and live off the land as best they could. The Secret History of the Mongols portrays Hoelun as a strong woman able to gather her children together and make a new life for themselves, her son, of course, going on to create one of the world’s greatest ever empires.

Toregene

Toregene Khatun (aka Doregene-Qatun, r. 1241-1246 CE), the former wife of the Merkit prince Qudu, reigned as regent after her husband Ogedei Khan’s death in 1241 CE. She held power until a great council of Mongol leaders elected Ogedei’s successor and Toregene’s son, Guyuk Khan, in 1246 CE. Toregene’s reign is not looked on favourably by contemporary sources, but these are Chinese and so, in effect, written by the enemies or conquered subjects of the Mongols.

Although she is credited with having great intelligence, shrewdness, and formidable political skills, particular criticism is made of her heavy taxation policies which included the privatisation of tax-collecting whereby tax collectors could keep anything for themselves above and beyond a pre-agreed amount for the territory under their supervision. Revenues were increased but at the cost of corruption and an overburdening of farmers. Other criticisms included her (alleged) willingness to listen rather too much to the Muslim advisors close to her (especially a Persian slave named Fatima), and her manoeuvres to remove any obstacle to her son becoming the next khan, including the unnecessary delaying of the next khan’s election. Toregene also fostered diplomatic ties with various princes and gave out lavish gifts to increase the support base for her son, a process she was able to carry out thanks to her delaying tactics and taxation policies. She must have died a happy woman, passing away in 1246 CE shortly after her son Guyuk had finally become Great Khan (r. 1246-1248 CE).

Sorghaghtani

Sorghaghtani Beki (aka Sorqoqtani, d. 1252 CE) was a Kerait princess who came to prominence as the widow of Tolui (c. 1190 – c. 1232 CE) and sister of Begtutmish Fujin, widow of Jochi, a son of Genghis Khan. Tolui was the youngest son of Genghis Khan and father of Mongke Khan (r. 1251-1259 CE) and Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294 CE), but he died around the age of 40; his lands in northern China and tribal position were maintained by Sorghaghtani. The princess may have warned Batu Khan, leader of what would become the Golden Horde and the western khanate of the Mongol Empire, of the plans of Guyuk Khan, Great Khan at the time, to attack Batu. In the event, Guyuk died before such a campaign could get started but Batu may have shown his gratitude by endorsing Sorghaghtani’s son Mongke who was elected Guyuk’s successor.

Oghul Qaimish

Oghul Qaimish (aka Oqol-Qaimish, r. 1248-1251 CE), was the wife of Guyuk Khan, and when he died in 1248 CE of poisoning, she reigned as regent. Oghul infamously dismissed, in 1250 CE, an embassy from King Louis IX of France (r. 1226-1270 CE), telling his ambassador Friar Andrew of Longjumeau that a great tribute would be required if his nation was to avoid destruction by a Mongol army. Oghul’s reign had little to distinguish it, and she largely stayed in the background of politics. Her one notable policy was to increase taxes for the peasantry from the traditional one in every hundred animals to the unrealistic one in ten animals.

Oghul would hold power until 1251 CE when Mongke Khan was elected ruler. Oghul was ultimately taken prisoner, her hands stitched together with leather thongs, and then put on public trial by Mongke in December 1252 CE as he purged all parts of the state he considered loyal to the previous regime, particularly the Ogedei clan. At her trial, Oghul was stripped of her clothes and accused of being rather too involved with shamanism for the good of the state and, much worse, guilty of treason. Found guilty, Oghul was thrown into the Kerulen River wrapped in a felt sack – a fate usually reserved for witches in Mongol justice as it was believed that evil cannot cross running water and may even be purified by it.

Bibliography

- Broadbridge, A.F. Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire. (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Buell, P.D. Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire. (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2018).

- Ebrey, P.B. Pre-Modern East Asia. (Cengage Learning, 2013).

- Lane, G. Daily Life in the Mongol Empire. (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2009).

- May, T. The Mongol Empire. (Edinburgh University Press, 2018).

- Morgan, D. The Mongols. (Wiley-Blackwell, 2019).

- Saunders, J.J. The History of the Mongol Conquests. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

- Turnbull, S. Mongol Warrior 1200-1350. (Osprey Publishing, 2003).

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 10.30.2019, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.