The Sino-Japanese War provided something very new—a modern and highly mechanized war against a foreign foe.

By Dr. John W. Dower

Ford International Professor of History, Emeritus

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Prints and Propaganda

The Sino-Japanese War began in July 1894 and ended in China’s shattering defeat in April 1895. It involved battles on land and sea; began with fighting in Korea that spilled over the Yalu River into Manchuria; witnessed the opening of a second front on the Liaotung (Liaodong) Peninsula and against Chinese fortifications at Weihaiwei as well as Port Arthur; and eventually involved a Japanese assault on the distant Chinese island of Formosa (Taiwan).

On the Japanese side, approximately 240,000 fighting men were mobilized for the campaigns in Korea and China proper, along with another 154,000 behind-the-lines laborers. Battlefield fatalities were surprisingly low, numbering only around 1,400; additionally, many died of illnesses, particularly those caused by severe winter conditions. Another 50,000 troops and 26,000 laborers were deployed in the relatively ignored Formosa campaign, where Japanese losses were actually higher. Overall Chinese casualties were much greater. In the battle for Port Arthur alone, for example, it is estimated that as many as 60,000 Chinese, including civilians, may have been killed.

In this moment of heady triumph, Japan did indeed seem to have “thrown off Asia” and gained recognition as a modern power, just as Fukuzawa had urged more than a decade earlier. This great demonstration of military prowess not only hastened the end of the unequal treaties that the foreign powers had saddled Japan with ever since the 1850s. It also opened the door to an extraordinary, almost unimaginable prize: the conclusion (in 1902) of a bilateral military alliance with Great Britain.

As time would show, however, this proved a costly triumph for everyone involved. In taking the imperialist powers as a model even while condemning their arrogance and aggression, the Japanese had adopted an inherently ambiguous and contradictory role. And in “throwing off” China as they did—not merely decisively but also derisively—they exhibited a racist contempt for other Asians that, even today, can take one’s breath away.

Lafcadio Hearn, the distinguished writer and long-time resident of Japan, immediately recognized the perilous nature of the new world Japan had entered. In 1896, the year after the war ended, he wrote this:

The real birthday of the new Japan … began with the conquest of China. The war is ended; the future, though clouded, seems big with promise; and, however grim the obstacles to loftier and more enduring achievements, Japan has neither fears nor doubts.

Perhaps the future danger is just in this immense self-confidence. It is not a new feeling created by victory. It is a race feeling, which repeated triumphs have served only to strengthen.

Quoted from Hearn’s book Kokoro by Shumpei Okamoto in Impressions of the Front

Nothing reveals this “race feeling” more graphically than the lively woodblock prints through which Japanese on the home front visualized—and grew rapturous over—what was taking place.

Although the Sino-Japanese War lasted less than a year, woodblock artists churned out around 3,000 works of ostensible battlefront “reportage”—amounting, as Donald Keene has pointed out, to an amazing ten new images every day.

This was not “high art.” The woodblock print itself was a popular art form that dated back only to the 17th century and found its audience in an emerging class of ordinary city dwellers. The prints were neither costly nor meant to be cherished and preserved as timeless creations. They were designed to amuse and entertain—and to introduce an untidy mass audience to worlds of hitherto unimagined beauty and fascination, whether this be courtesans and actors in the pleasure quarters, or places the print viewer might never personally see, or purely imagined realms of heroes, villains, ghosts, grotesqueries, and erotic indulgence. In subject, style, and audience, the exuberant woodblock prints were the antithesis of most things associated with tasteful upper-class classical art.

What we now regard as the great flowering of the woodblock-print tradition ended at the very end of the feudal era with artists of surpassing genius such as Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858). The “Meiji prints” that followed were less esteemed. Even generations later, after collectors and connoisseurs had belatedly come to recognize the enormous creativity and enduring value of the feudal-era prints—had accorded them, as it were, a kind of “classic” stature of their own—the prints of the modern era were generally held in low regard.

It is only in recent decades that the Meiji prints have drawn serious attention. Partly, it must be acknowledged, this came about because they were lying around in considerable quantity and much less expensive to collect than the suddenly pricey feudal prints. Partly, too, this rise in interest occurred because these later prints were belatedly seen to have a distinctive vigor all their own.

There was, however, a third factor behind the rediscovery of Meiji prints. As historians began to turn increasing attention to “popular” culture (beginning around the 1960s), and to place more weight on studying “texts” that went beyond written documents per se, graphics and images of every sort were suddenly recognized to be a vivacious way of visualizing the past. One could, in effect, literally see what people in other times and places were themselves actually seeing—and then try to make sense of this. One could “read” visual images much as one might read the written word—not simply as art, but also as social and cultural documents.

In the decades following Perry and the opening of Japan, woodblock prints became a major vehicle for presenting a picture of current affairs. When foreigners first came to the newly-opened treaty port of Yokohama in the early 1860s, for example, it was the woodblock artists who seized this opportunity to churn out “Yokohama prints” that purported to show how the Westerners lived. If we wish to see how Japanese at the time visualized the upheaval that culminated in the Meiji Restoration itself, or how they pictured the vogue of Westernization that followed in the 1870s and 1880s, there is no more vivid source, once again, than these popular prints.

Similarly, it is to the modern woodblock prints that we now turn to recapture a sense of the emotional popular support that accompanied Japan’s emergence as an aggressive, expansionist power at the end of the 19th century. Nationalism, militarism, imperialism, a new sense of cultural and even racial identity—all found their most flamboyant expression here. Indeed, the popular prints did not merely “capture” this sentiment; they played a role in pumping it up. They are the most dramatic and easily accessible source we have for getting a “feel” for the redefinition of national identity that went hand-in-hand with Japan’s debut as a major power.

In the West, the “journalistic” role that woodblock prints played in late-19th-century Japan was largely filled by publications that featured engravings and lithographs based on photographs. By the time of the Sino-Japanese War, popular periodicals such as the Illustrated London News also featured photographs themselves. The impression of the world these Western graphics conveyed was, as a rule, both more “realistic” and more detached. They were literally, and often figuratively as well, colorless—a sharp contrast to the vivacious and highly subjective woodblock prints.

Japanese photographers did cover the Sino-Japanese War; an evocative woodblock by Kobayashi Kiyochika even takes them as its subject, standing in the snow and photographing the troops with a large box camera on a tripod.

It was only after this war, however, that photography entered the pages of Japanese newspapers and magazines in a substantial way. Until then, the woodblock illustrations held center stage as graphic “reportage.” The Sino-Japanese War marked the apogee of this phenomenon—the unquestioned high point of Meiji woodblock art. War prints were the most vivid, dramatic, emotional medium through which Japanese on the home front could follow—almost literally day-by-day—the momentous conflict on the other side of the Yellow Sea.

There was no counterpart to this on the Chinese side—no such popular artwork, no such explosion of nationalism, no such nation-wide audience ravenous for news from the front.

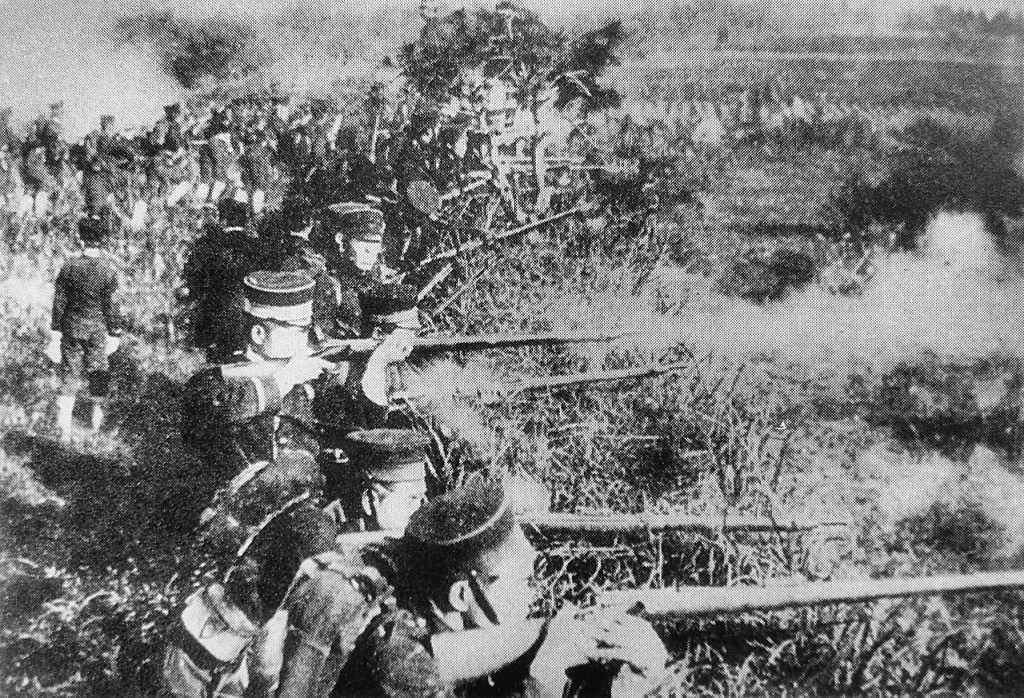

As it happens, there does exist a rare, anonymous Japanese woodcut engraving of one of the greatest battles of the Sino-Japanese War, the capture of Port Arthur in November 1894. Identical in size with a standard-size woodblock triptych (14 x 28 inches), this suggests how Japanese graphic artists might have depicted the war if they had adopted the Western practice of detailed black-and-white renderings. The detail is, indeed, meticulous—so obsessively fine that the overall impression is almost clinical. The contrast to the animated multi-colored woodblock prints could hardly be greater.

A well-known print by Mizuno Toshikata depicting a battle in July 1894 suggests many of the conventions that came to distinguish the Sino-Japanese War prints in general. This was the opening stage of the war, and the print’s title alone conveys the fever pitch of Japanese nationalism: “Hurrah, Hurrah for the Great Japanese Empire! [Dai Nihon Teikoku Ban-Banzai!] Picture of the Assault on Songhwan, a Great Victory for Our Troops.”

In Toshikata’s rendering, stalwart Japanese soldiers with a huge “Rising Sun” military flag in their midst advance against a Chinese force in utter disarray. Can we trust the veracity of this artistic rendering? Surely we can, for on the right-hand side of Toshikata’s print we see a delegation of Japanese “newspaper correspondents” that includes at its head not one but two artists, identified by name. Depictions such as this very print, Toshikata seems to be assuring his audience—and right at the start of the war—could be trusted to be accurate.

The overwhelming majority of war prints were, in fact, nothing of the sort. Although some artists and illustrators did travel with the troops, the woodblock artists remained in Japan—catching the latest reports from the front as they came in by telegraph and rushing to draw, cut, print, display, and sell their pictured version of what they had read before this particular “news” became outdated. (Occasionally prints were initiated in anticipation of the actual event!) Toshikata was offering an imagined scene—a set piece that quickly became formulaic.

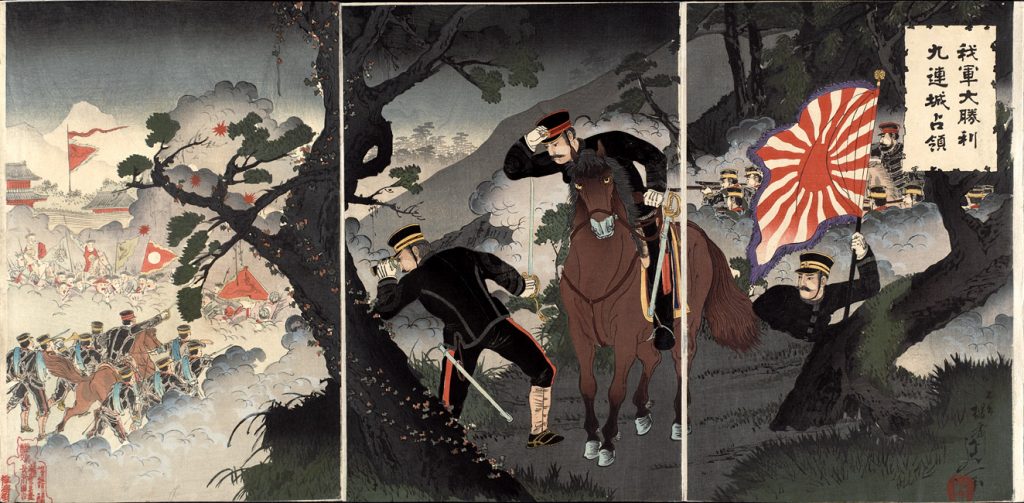

In these circumstances, prints often simply “quoted” other prints. In early November 1894, for example, Toshikata’s colleague Watanabe Nobukazu produced a rendering of “Our Forces’ Great Victory and Occupation of Jiuliancheng” that bore close resemblance to Toshikata’s “Hurrah, Hurrah” of over three months earlier. Disciplined soldiers looked down from on high, other troops advancing below them. The same military flag fluttered in the same right hand panel of the triptych; a bent and gnarled pine, so beloved in Japanese art, was again rooted in the center of the image; the foe retreated in the far distance.

That same November, Ogata Gekkō used much the same flag, pine, and craggy bluff to illustrate the army’s advance on Mukden.

The heroic officer in Toshikata’s “Hurrah, Hurrah” print, striking a dramatic pose with his sword held high, also quickly became a stock figure. He might have stepped out of a Kabuki play (or a traditional print of a Kabuki actor or legendary warrior)—and certainly did step into a great many other scenes from the Sino-Japanese War.

Toshikata himself introduced virtually the identical hero under many different—and always real—names in his war prints. (His Japanese fighting men almost always were in movement from right to left, as if the print were a map and the viewer eye-witness to Japan’s westward advance onto the continent. This overlapped, of course, with the conventional right-to-left movement of writing and reading, and conventional unfolding picture scrolls.) Toshikata’s archetypical hero appeared, for example, as “Lieutenant Commander Sakamoto” on the warship Akagi; as “the skillful Harada Jūkichi” in the attack on Hyonmu Gate (the sword here turned into a bayonet); as “Captain Matsuzaki” in the battle of Ansong Ford; and as “Captain Higuchi” in a near mythic battle at the “Hundred-Foot Cliff” near Weihaiwei (see details below).

The same Captain Higuchi—flourishing his sword and leading his forces in attack while clutching a Chinese child found abandoned on the battlefield—steps into a print by Migita Toshihide in almost the identical heroic pose. Even the horizontal lines that streak across the scene to suggest gunfire appear in both prints. When Toshihide depicts “Colonel Satō” in an entirely different battle, he essentially just turns his Captain Higuchi in the opposite direction and has him braving the bullets while holding a flag instead of a child. Later, when the Japanese army moved south to occupy the Pescadores, Toshihide’s intrepid officer metamorphosed as “Captain Sakuma raising a war cry”. Gekkō’s version of the bearded “Colonel Satō charging at the enemy” turned the hero back to the usual charging-left direction. Ginkō placed his intrepid hero-with-a-sword (in this case, unnamed) on horseback in his rendering of the great battle of Pyongyang.

The Predictable Pose of the Hero

Although prints of the Sino-Japanese War purported to depict actual battles and the exploits of real-life officers and enlisted men, the “Hero” almost invariably struck a familiar pose—like a traditional Kabuki actor playing a modern-day warrior. Officers in austere Western-style uniforms brandished swords (the counterpart for enlisted men was the bayonet). Their posture was resolute, their discipline obvious, their will transparently unshakable.

Much of the appeal of the prints to Japanese on the home front resided in predictability of this sort—much like seeing the same theatrical play staged and performed by different directors and actors. Repetition is reassuring. Comfort lies in the familiar—not just recognizable posturing, but the larger formulaic melodrama of heroic struggle and rousing triumph. Sometimes the print even became a crowded stage in which the artist literally threw a spotlight (here a searchlight) on the disciplined Japanese annihilation of archaic China. A dramatic “searchlight” print by Toshimitsu of “Our Army’s Great Victory at the Night Battle of Pyongyang,” is a typical example of this.

As these prints make clear, the other side of stirring triumphalism was thoroughgoing defeat of the enemy. This, too, followed predictable patterns: the Chinese foe overwhelmed and in disarray, smashed to the ground and sent flying through the air, lying dead as rag dolls on the ground—often but half seen, or half buried in snow.

Routing the Foe

While Japanese fighting men were invariably depicted as heroic, renderings of the Chinese foe also followed predictable patterns. Their brightly colored, old-fashioned garments posed a sharp contrast to the austere Western-style uniforms of the Japanese, and they were commonly depicted as being overwhelmed, routed, and slaughtered. Such images graphically captured the double implications of “Throwing off Asia” rhetoric: first, getting rid of old-fashioned and non-Western attitudes, customs, and behavior in Japan itself; and second, literally overcoming Japan’s Asian neighbors, who were perceived as having failed to respond to the Western challenge, and thereby imperiling the security of all Asia. Such attitudes reflected the survival-of-the-fittest ideas that the Japanese learned from the Western powers themselves.

Clothing, too, rendered the two sides as different as night and day. In contrast to the disciplined Japanese fighting men in their somber Western-style uniforms, the Chinese wear loose garments in almost riotous colors. They appear strange, old-fashioned, almost picturesque—trapped in a time warp and certainly out of place in a modern war. Japan’s heroes are up-to-date—always moving as a disciplined unit, but at the same time frequently singled out by name. The Chinese, with very few exceptions, emerge as a disorderly mass redolent of a backward and bygone time.

There is nothing unique about valorizing and personalizing one’s own side while diminishing the enemy. In the Sino-Japanese War, however, the Japanese were encountering war in unfamiliar ways. To begin with, although they possessed a deep history of warrior rule dating back to the late-12th century, this had actually ended with several centuries of peace. From the early-17th century until the arrival of Commodore Perry in the 1850s, Japan’s samurai elite had been warriors without wars.

Story-tellers and actors and artists in late-19th-century Japan thus had a rich tradition and repository of images concerning medieval warfare to draw upon—but no major recent wars apart from domestic conflicts just before and after the Meiji Restoration. The long Tokugawa period (1600–1868) that preceded the Restoration produced famous swordsmen rather than battlefield heroes. Beyond this, moreover, the “samurai” battlefield heroes of earlier times had come from a hereditary elite; there were few commoners among them.

The Sino-Japanese War thus provided something very new—not only real war and real battlefield heroes, and not only heroes from the lower ranks and lower classes, but also a modern and highly mechanized war against a foreign foe. Before the Restoration, Japan was not a “nation” per se. It did not define itself vis-à-vis other countries or interact in any serious way with them. The Restoration marked the real initiation of what we now call “nation building”—and the Sino-Japanese War carried this to an entirely new level. When Lafcadio Hearn spoke of the conquest of China as marking “the real birthday of the new Japan,” it was this sense of nationalistic—and now imperialistic—modernity that he had in mind.

There was tension, danger, huge risk in all this—and, certainly as the artists conveyed it, exhilarating beauty as well. Japan’s leaders threw the dice when they took on China in 1894. Indeed, most foreign observers initially assumed that China—with its rich history and vast size and population—would prevail. Instead, as the Japanese war correspondents and artists breathlessly conveyed to their fired-up audience back home, Japanese victories came swiftly. Chinese forces were routed. Japan had mastered modern war—not only on land, but also on the sea.

Most of the woodblock artists who tried to capture this excitement were young. (In 1894, when the war began, Kiyochika, the doyen of these artists, was 47 and Ogata Gekkō 35. Toshikata was 28, Toshihide 31, Taguchi Beisaku 30, Kokunimasa 22, Watanabe Nobukazu a mere 20. Toshimitsu’s birth date is unclear, but he was probably in his late 30s.) They not only imbibed the new nationalism, but seized the moment to introduce new artistic subjects (the weapons and machinery of modern war, explosions, searchlights, Asian enemies, real contemporary heroes in extremis)—and, with this, what they perceived to be a new Western-style sense of “realism” that extended beyond subject matter to new ways of rendering perspective, light, and shade.

When all was said and done, what they visualized in their propagandistic “war reportage” was a beautiful, heroic, modern war. For what turned out to be a fleeting moment, the woodblock artists imagined themselves to be splendidly up-to-date.

Kiyochika’s War

The energy and artistic skill of the best war prints are all the more remarkable when we keep in mind the haste of their composition. Some sense of the impressive nature of this accomplishment can be gleaned by an overview of prints by Kiyochika, the most esteemed of these artists, who is calculated to have produced more than seventy triptychs during the brief ten months of the Sino-Japanese War. Kiyochika’s impressions of the front ranged from the lyrical to the atrocious, sometimes even bringing these two extremes together.

War Prints of Kobayashi Kiyochika

In Kiyochika’s war, a cavalry officer stands before a horse in a quilted blanket, a rowboat buried in slabs of ice by his feet, and observes troops crossing a frozen river in the pale glow of dawn. We can almost feel the numbing cold. In a comparably crisp winter scene, three officers stand around a telescope on a snow-buried bluff at Weihaiwei, looking down on a Chinese fleet in the harbor that they will soon destroy. (Kiyochika’s early-morning colors here and elsewhere often show a Western influence art historians have called “Turneresque,” after the English master of painterly light.)

In other Kiyochika prints, a blizzard whips across an army regiment almost invisible in the blinding snow; one must look twice to see the crouching figures. Campfires pierce the dead of a winter night as a shadowy mounted figure pauses before a tent where, as we know from the Red Cross flag, the wounded are being tended. An exhausted officer asleep on the front dreams of returning as a hero to his family back home.

Occasionally, Kiyochika “quotes” himself with a subtlety worlds apart from the repetitive figures and themes found in prints by less accomplished artists like Toshikata. In another winter scene, for example, officers in heavy overcoats (one mounted on another horse with a quilted blanket) are posed in falling snow before a shadowy line of soldiers with their rifles held upright like a picket fence. Another print depicts a naval officer wading ashore from a rowboat that had delivered him from a shadow warship. Behind him, sailors hold their long oars perfectly upright in the light fog—much like the rifles in the snowstorm. A depiction of high-ranking officers questioning local Chinese informants after a snowstorm frames the deceptively serene scene in a rainbow.

Kiyochika brought the same adroit touch to combat scenes, and several of his battlefront prints are classic expressions of the mystique of Japan’s destiny as a modernizing power in a backward Asian world. In a dramatic rendering of an injured cavalry officer (Captain Asakawa) and his aide surrounded by the foe, three dead Chinese lie in pelting rain as the officer steps over his dead mount while his mortally wounded aide leads his own horse forward for Asakawa to ride. The slanting rainfall evokes pre-Meiji woodblock masters such as Hiroshige, but the scene itself is pure Kiyochika.

A similarly somber atmosphere permeates Kiyochika’s rendering of “Harada Jūkichi” scaling the Hyonmu Gate in Pyongyang (the subject of one of the Toshikata prints introduced earlier). Here the moon looks down on the hero standing high on a rampart. At his feet lies a slain foe who is not merely garbed in an old-fashioned tunic, but also barefoot—as strong (and subtle) a statement of backwardness as one can imagine. As fire rises in the distance behind him, Harada gazes over a vast and almost empty vista, prickled with tiny starbursts of light, which occupies half the print. He might almost be looking to the future.

The big guns and spectacular explosions of modern warfare dazzled the woodblock artists, and Kiyochika met the challenge of portraying this with particular verve. Japanese fighting men throw their arms up in victory upon capturing the huge Chinese cannon at Weihaiwei. In a dramatic rendering of the artillery on the warship Matsushima (which took heavy damage in a battle near the end of 1894), a sailor dying by the gun is consoled by being told that victory is assured. A sequence of prints depicting the “Great Victory in the Battle of the Yellow Sea” revels in men fighting through heavy enemy bombardment, artillery fire bursting like fireworks in a night sky, the sea itself turned into a gigantic explosion.

In another print of the naval war, Kiyochika let his imagination run wild. His subject was the cruiser Zhiyuan, which sank near the mouth of the Yalu River. Where most prints imagined the Japanese annihilating their opponents on choppy seas, Kiyochika’s doomed vessel is already underwater, plunging to the bottom with tiny drowned figures floating suspended in the brine. Standing in almost giddy contrast to this is a startling depiction of sailors cheering the sinking of a Chinese warship on the deck of their small torpedo boat. Amid turbulent waves, they are already drinking in celebration and obviously getting sloshed in more ways than one.

Many Kiyochika prints convey a cartoon quality that foreshadows the manga usually associated with Japanese popular culture after World War Two. (Devotees of manga history point to the graphics of the Sino-Japanese War as a decisive turning point). Dynamite and artillery barrages explode in red, orange, and yellow fireballs. Enemy figures become flattened into cartoonish black silhouettes, and picked off by Japanese riflemen as if they were targets in a shooting gallery. Japanese infantry creep along the ground against a beautifully stylized dusk sky, half men and half almost invaders from another world.

Kiyochika’s highly aesthetic and romanticized war ends not merely in righteous slaughter but in the sheer pleasure of delivering death. In one vigorous print, his action-figure hero, camouflaged with straw, bayonets a Chinese in the back so ferociously the victim is lifted high in the air. In another rendering of impressive technical accomplishment, where Kiyochika captures a sense of the whirlwind turbulence of a dusty battlefield, the routed foe, in brilliant cobalt tunics, simply leap out as grotesque and pitiful—cringing, begging for mercy, tumbling up-side-down.

Perhaps the single most appalling woodblock celebration of the Sino-Japanese War is also Kiyochika’s. It depicts victorious Japanese forces blowing trumpets and raising their arms to heaven in a banzai cheer while standing on a mound of Chinese corpses.

In a series of single-block prints (as opposed to the usual triptych), Kiyochika offered a “Mirror of Army and Navy Heroes” that, as usual, paid tribute to real-life individuals. Typically, his heroes ran a gamut of settings—in this instance, from a wise admiral calmly reading a newspaper to “Captain Awata” cleaving the skull of his foe with his sword. Between these extremes, the artist’s heroes included a soldier kind to Chinese civilians and a blinded sailor reverently touching one of the big guns that had brought victory to the Japanese side.

Kiyochika turned his hand to outright cartooning as well. His contributions to a wartime series called “Hurrah for Japan: One Hundred Selections—One Hundred Laughs” include Japanese soldiers shaving the wooden head of a Chinese man with a wood-plane, laughing at a Chinese man frightened by a snowman, and attacking a terrified Chinese sick man in a bed. Other woodblock cartoons by Kiyochika ridiculing the Chinese were issued under titles such as “Pig in a Serious Condition Series: The Sino-Japanese War” and “Dance of Cowardice Series: The Sino-Japanese War.” Another Kiyochika cartoon depicts that most universal expression of martial ardor: children playing war games. Here the “Chinese” are prisoners of war.

“Old China, New Japan”

In contrast to Kiyochika’s distinctive thematic compositions, many woodblock artists reveled in the tumult and chaos of the battlefield. They offered their audience riotous melees—congested spectacles that invite the viewer to scrutinize the scene, sort out the combatants, discover any number of intimate details. Sometimes the detail is so dense it is startling to be reminded that these popular artworks were usually tossed off in a matter of days.

Still, predictable patterns give order to this chaos. Discipline (the Japanese side) prevails over disarray (the Chinese). The sword-wielding Japanese officer and bayonet-thrusting infantryman are invariably present—and easy to locate, since their black uniforms contrast sharply to the flamboyant clothing and paraphernalia of the Chinese. The enemy’s garments vary from battle to battle but are always colorful and frequently decorated with elaborate designs. Their headgear suggests that they employ many different haberdashers. In contrast to the ubiquitous rising-sun-with-rays military flag of the Japanese, Chinese banners and ensigns feature a range of designs. Sometimes the enemy employ archaic weapons such as a three-prong pike or trident. Here and there they carry old-fashioned round shields decorated with garish face-like designs. The braided queues worn by Chinese men often stretch out like ropes or snakes; sometimes they are coiled in a bun. In short, the Chinese are depicted as being riotous in every way—disgracefully so in their behavior, and delightfully so in their accoutrements.

Heroic encounters between relative equals are not entirely absent from these depictions, however. A fairly typical rendering of a melee by Toshimitsu, for example, includes two swordsmen dueling to an uncertain finish. With comparable even-handedness, several quite spectacular prints by unidentified artists render individuals on both sides as almost mirror images of one another—faces frozen in Kabuki-like determination or similarly marked by rather individualized touches.

Such suggestions of relative equality emerge especially clearly in depictions of combat between mounted officers. These figures stand out from the tumult around them by virtue of their horses alone, but this is not the only source of shared identity. On both sides these combatants were men of comparable rank, accomplishment, and ability.

In one print by an unidentified artist, a clash between two cavalrymen is actually turned into a spectator sport. Fighting men pause to watch, and a few Chinese have even climbed a tree to get a better view.

A few prints detach cavalry combat from the congestion of battlefield tumult and place it alone at stage center, occasionally even giving the names of Chinese generals involved.

The single most honorable Chinese singled out in the war prints, however, was not a mounted officer but an admiral—the venerable Ding Juchang, whose fleet was destroyed after hard fighting off Weihaiwei early in 1895. After surrendering in a courteous exchange of messages between the two sides, Admiral Ding Juchang committed suicide by taking poison. When the Chinese warship carrying his body left the harbor, the Japanese fleet dropped their flags to half-mast and fired a salute. Death by one’s own hand held an honorable place in Japan’s own warrior tradition, of course; be that as it may, several woodblock artists commemorated the admiral’s death with respectful renderings. One of the best of these, by Toshikata, imagines Admiral Ding Juchang seated in an elegant room holding a cup of poison in his hand.

In another well-known print, Toshikata pitted his Japanese hero, “Captain Awata,” against a Chinese antagonist of no status but undeniably formidable strength—in this case, a giant on Taiwan whose weapon of choice was a halberd. In his treatment of this celebrated encounter, Toshikata portrays the Chinese foe with respect. More typical, however, was Toshihide’s rendering of the same duel, in which Awata administers the coup de grâce to a twisted figure collapsing from a lethal blow to the head—his straw hat flying through the air, clearly torn where Awata’s sword blade sliced through. (This is the same Captain Awata whom Kiyochika lovingly portrayed cleaving the enemy’s skull.)

Devil in the Details

When all was said and done, denigration ruled the day when it came to portraying the Chinese foe. As the prints so graphically reveal, moreover, such disdain frequently carried both a harsh racist charge and an undisguised edge of pure sadism. The devil, as always, is in the details. The Chinese are slashed with swords; skewered with bayonets (often run through from behind, as in Kiyochika’s showing); shot at close range; beaten down with rifle butts; strangled; crushed with boulders; pounded with oars while floundering in the sea. They tumble off cliffs and warships like tiny rag dolls. In one print, a civilian caught in battle lies crumpled on the ground with a still-open parasol on his corpse, conspicuous once again by his gaudy and (in Japanese eyes) outlandish clothing.

It is particularly sobering to keep in mind that this was not on-the-scene “realism.” The woodblock artists worked largely out of their own imaginations, tailoring this to news reports from the front. They were commercial artists catering to a popular audience, and this was the war Japanese wished to see.

Admiral Ding Juchang, the Chinese generals on their horses, the occasional battlefield enemies treated as just as human as the Japanese are exceptions that prove the rule. The prototypical Chinese is grotesque. His face is contorted, his body twisted and often turned topsy-turvy, his demeanor in most cases abject. Battlefield scenes routinely include cringing foe pleading for their lives—even while making clear that the emperor’s stalwart heroes should and would pay no heed to such cowardice. The braided queue becomes, in and of itself, a mark of backwardness and inferiority; in more than a few battle scenes, Japanese stalwarts grasp this while dispatching their victim. (Pulling Chinese men by their “pigtail” was also a favorite image among American and English cartoonists until the overthrow of the Manchu dynasty in 1911, after which this hairstyle was no longer mandatory for ethnic Chinese males.)

Chinese prisoners of war, usually bound with thick rope, also drew attention. Ōkura Kōtō imagined “Captain Higuchi” (lionized for picking up a Chinese child on the battlefield) confronting three such captured Chinese—a particularly suggestive scene, combining as it did denigration of the “old” China with chivalrously rescuing “young” (or future) China, and all this in front of a piece of heavy artillery. Toshihide and others similarly dwelled on Chinese officers kneeling in supplication before their captors.

Many of the basic themes of Japanese war propaganda are combined in this print. The disciplined and victorious Japanese stand before the machinery of modern warfare in their Western-style uniforms, while Chinese prisoners in old-fashioned garb—symbols of backward “old Asia”—kneel before them.

Kokunimasa offered a harsh “Illustration of the Decapitation of Violent Chinese Soldiers” that included a lengthy inscription. The benevolence and justice of the Japanese army, this text explained, equaled and even surpassed that of the civilized Western nations. By contrast, the barbarity of the Chinese was such that some prisoners attacked their guards. As a warning, the Japanese—as depicted in the print—had beheaded as many as 38 rebellious prisoners in front of other captured Chinese. The Rising Sun military flag still fluttered in one panel of Kokunimasa’s print; the stalwart cavalry officer still surveyed the scene; the executioner still struck the familiar heroic pose with upraised sword. The subject itself, however, and severed heads on the ground, made this an unusually frightful scene.

The long description on this particularly grisly scene contrasts the “civilized” behavior of the Japanese to the “barbarity” of the Chinese—and as an example of the latter tells how Chinese prisoners rebelled against their captors and were executed as a warning to other Chinese.

This is an extraordinary declaration given the atrocious nature of the graphic. At the same time, it is perfectly in accord with the rhetoric of Western imperialists of the time, who similarly portrayed their brutal suppression of peoples in other lands as part of a “civilizing mission.”

The derision of the Chinese that permeates these prints found expression in other sectors of popular Japanese culture. The scholar Donald Keene, for example, has documented how popular prose, poems, and songs of the war years took similar delight in lampooning the “pumpkin-headed” Chinese and making jokes about their slaughter. (It was around this time that the pejorative Japanese epithets chanchan and chankoro became popular, amounting to a counterpart to the English-language slur “chink.”)

Even today, over a century later, this contempt remains shocking. Simply as racial stereotyping alone, it was as disdainful of the Chinese as anything that can be found in anti-“Oriental” racism in the United States and Europe at the time—as if the process of “Westernization” had entailed, for Japanese, adopting the white man’s imagery while excluding themselves from it. This poisonous seed, already planted in violence in 1894–95, would burst into full atrocious flower four decades later, when the emperor’s soldiers and sailors once again launched war against China. Ironically, the Japanese propaganda that accompanied that later war involved throwing off “the West” and embracing “Pan-Asianism”—but that is another story.

Symbolic “China”

Because racism in the age of imperialism is most commonly associated with “white supremacism” (and the smug rhetoric of a “white man’s burden”), this explosive outburst of Japanese condescension toward China and the Chinese seems all the more stunning. In the Western hierarchy of race, so-called Orientals or Asiatics or Mongoloids were lumped together—below the superior Caucasians and above the “Negroid.” In their inimitable way, the Japanese promoted these stereotypes where the Chinese were concerned, even while trying to demonstrate their own identity with the Caucasians.

What made this even more disconcerting was the intimate overlay of race and culture in the case of Japan and China. No non-Chinese society was more indebted to China. Japan’s written language, its great traditions of Buddhism and Confucianism, vast portions of its finest achievements in art and architecture—all came from China. In an abrupt phrase familiar to all literate Japanese, even in the Meiji period, China and Japan were culturally as close as “lips and teeth.”

But that, of course, was the point—and what made this outburst of anti-Chinese sentiment a very peculiar sort of racism on the part of the Japanese. The Chinese were contemptible because they were deemed inept. At the same time, however, “China” was symbolic and self-referential. “China,” that is, stood for “Asia.’ It stood for “the past.” It stood for outmoded “traditional values.” It stood for “weakness” vis-à-vis the Western powers. It stood, coming even closer to home, for “evil customs of the past” that Japanese leaders ever since the Meiji Restoration argued had to be eradicated within Japan itself if their nation—and Asia as a whole—were to survive in a dog-eat-dog modern world.

“Old” China was the Anti-West, the Anti-Modern (a notion China’s own Communist leaders would later embrace with a vengeance themselves). As a consequence, while the corpses were unmistakably and brutally Chinese, they stood for a great deal more as well.

To return to Fukuzawa’s famous phrase, killing Chinese amounted to “throwing off Asia” in every conceivable way. This was seen to be essential to Japan’s security, its very survival. It was deemed progressive. It amounted, when all was said and done, to embracing a “modern” kind of hybridization. Where the old Japan had been distinguished by enormous indebtedness to traditional Chinese culture, the new Japan would be distinguished by wholesale borrowing from the modern West.

At the same time, of course—as is true of nationalism everywhere—it was necessary to think oneself unique. In the Japanese case, this was accomplished by “reinventing” the mystique surrounding the throne and imperial family. It was not coincidental that the war against China coincided with the consolidation of a modern emperor system under the new constitution of 1890.

From the Japanese perspective, the denigration of the Chinese that permeates the Sino-Japanese War prints was really secondary to the obverse side of this triumphal new nationalism. It was secondary, that is, to the story of the surpassing discipline and self-sacrifice of Japanese from every level of society. That is why many of the most memorable war prints do not depict the enemy at all, but rather focus on the Japanese alone. Sometimes they are simply battling raw nature (the fierce blizzards and turbulent seas), sometimes simply shown in control of the powerful machinery of modern warfare. Always there is a celebration of brave men engaged in a noble mission—throwing themselves against an ominous, threatening, but also thrillingly challenging and alluring world.

Thus Gekkō, who often reveled in particularly grisly combat details, devoted one print to a serene depiction of “Officers and Men Worshipping the Rising Sun While Encamped in the Mountains of Port Arthur.” (That the sun rose in the east, the direction of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, intensified the ideological implications of such worship.) Another Gekkō offering focuses on the solitary figure of “Engineer Superior Private Onoguchi Tokuji, Defying Death,” and yet another on “the Famous Death-Defying Seven from the Warship Yaeyama” rowing through high waves.

Nobukazu’s most famous war print is probably his heroic close-up rendering of “General Nozu” leading his horse and three men across a deep river in the moonlight. Toshihide paid tribute to “Sergeant Miyake” and a sturdy subordinate, who stripped to the waist and braved the frigid waters of the Yalu River to carry out their mission. An unidentified artist went Toshihide one better by depicting a certain “Sergeant Kawasaki” swimming across a turbulent rain-swollen river with a sword clenched between his teeth.

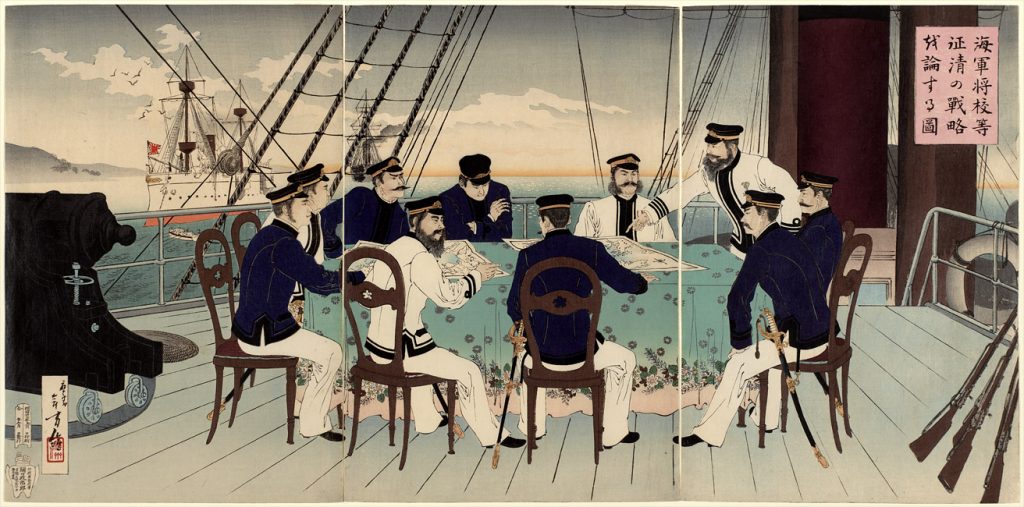

Toshikata (the maestro of the predictable pose with whom this discussion began) also captured this spirit of valor transcending any specific battle or foe without necessarily explicitly flourishing a sword or unfurling a Rising Sun flag. One of his most effective war prints, for example, simply depicts sailors poised almost like a group statue as they man one of their warship’s big guns. Another of his well-known scenes portrays naval officers seated on deck calmly planning strategy. Toshikata’s remarkable “Picture of the Fearless Major General Tatsumi” portrays the general sleeping “peacefully under a pine tree, taking his own life lightly.”

This was precisely the sentiment the Meiji leaders had devoted themselves to inculcating ever since the emperor’s 1882 “Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors.” Duty was heavy as a mountain, death light as a feather. These were free-floating heroes, ready to sacrifice themselves for the nation whenever and wherever they were commanded to do so. The precise enemy was secondary.

Among the last prints to come out of the Sino-Japanese War were depictions of the Chinese surrender in February 1895. All of the participating officials were rendered straightforwardly and reasonably realistically—and the impression that Japan had truly thrown off Asia could not have been conveyed more strongly. The Chinese envoys were garbed in traditional ceremonial gowns and caps; Japanese dignitaries wore formal Western dress; and both British and American diplomats were present, particularly to act as advisers to the Chinese side. There could be no doubt whatsoever concerning with which side the Japanese were identifying.

Selected Bibliography

Complementary Readings

1. Marlene Mayo, ed., The Emergence of Imperial Japan: Self-Defense or Calculated Aggression? (D. C. Heath, 1970). This collection of essays addressing Meiji Japan’s emergence as an imperialist power includes a particularly valuable “Prologue” by Yoshitake Oka, from which several of the quotations in the Essay derive. Oka’s concise essay is one of the best short overviews available of “Social Darwinist” and “Realist” thinking by late-19th-century Japanese.

2. Donald Keene, “The Japanese and the Landscapes of War,” in Keene’s Landscapes and Portraits: Appreciations of Japanese Culture (Kodansha International, 1971), 259-99. This essay by one of the most distinguished literary and cultural scholars of Japan is excellent for placing the woodblock prints of the Sino-Japanese War in the broader context of Japanese popular culture (and war enthusiasm) at the time. The essay has had several lives. See also Keene’s “The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and Its Cultural Effects in Japan,” in Tradition and Modernization in Japanese Culture, Donald Shively, ed. (Princeton University Press, 1971), 121-75; also the 1981 Kodansha reprint of Landscapes and Portraits, which is titled Appreciations of Japanese Culture.

3. Shumpei Okamoto, The Japanese Oligarchy and the Russo-Japanese War (Columbia University Press, 1970). This scholarly analysis is the best account of the politics of the Russo-Japanese War on the Japanese side. It concludes with discussion of the riots that erupted in Japan when the terms of the “Portsmouth peace settlement” were made public.

4. Richard Hough, The Fleet That Had to Die (Ballentine, 1960). Although not at all essential to understanding the background of the war prints, this readable account describes the ill-fated journey of the Russian Baltic Fleet as it sailed around the world to Port Arthur, only to be destroyed by Admiral Tōgō in the Battle of Tsushima in 1905. Hough’s narrative captures some of the flavor of the times on the (hapless) Russian side in a particularly colorful manner.

5. Henry D. Smith II, Kiyochika: Artist of Meiji Japan (Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1988). This short (and hard-to-find) publication provides an overview of the greatest Meiji woodblock artist, whose war prints—particularly of the Sino-Japanese War—receive close attention in the present Web site.

Illustrated English-Language Publications of Meiji War Prints

“Throwing Off Asia” is at present the most densely illustrated and accessible treatment of Meiji woodblock prints focusing on the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars. (The Essays alone include 165 prints, of which 111 depict the Sino-Japanese War and 34 the Russo-Japanese War.) There are four noteworthy published catalogs in English that feature the war images. These include prints not included in the MFA collection on which “Throwing Off Asia” is based, as well as interesting captions and commentaries.

6. Impressions of the Front: Woodcuts of the Sino-Japanese War, 1894-95 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1983). Devoted entirely to prints of the Sino-Japanese War, this excellent catalog is based on the extensive collection of Meiji war prints at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. A total of 86 full-color prints are reproduced (in small format), accompanied by generous commentary. The arrangement is chronological rather than thematic or by artist, enabling the reader to follow the course of the war visually. Essays by Shumpei Okamoto (on the war) and Donald Keene (on the prints) enhance the value of this hard-to-obtain publication. Impressions of the Front also includes maps, a battle chronology, and a bibliography.

7. The Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), Nathan Chaikin, ed. (Bern, Switzerland: privately published, 1983). This sumptuous volume reproduces 92 prints of the Sino-Japanese War, primarily from the Geneva-based collection of Basil Hall Chamberlain, a famous turn-of-the-century British expert on Japan. The full-page reproductions include many in color, and editor Chaikin provides detailed commentary on both the prints and the military history of the war. Organization is chronological, rather than by artist or theme.

8. In Battle’s Light: Woodblock Prints of Japan’s Early Modern Wars, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, ed. (Worchester Art Museum, 1991). Based on Meiji war prints from the Sharf Collection (before that collection was donated to the Boston Museum of Fine Art), this catalog includes prints from both the Sino-Japanese War (53 plates) and Russo-Japanese War (27 plates). Within this, grouping is by artist. Brief captions and commentary accompany each print.

9. Japan at the Dawn of the Modern Age: Woodblock Prints from the Meiji Era, Louise E. Virgin, ed. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2001). This exhibition catalog celebrates the donation of the Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection of Meiji prints (on which this present “Throwing Off Asia” web site is primarily based) to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The catalog contains 77 color plates (22 depicting Meiji Westernization and the emperor, 39 on the Sino-Japanese War, and 16 on the Russo-Japanese War), with brief commentaries for each. Also included are essays by Donald Keene, Anne Nishimura Morse, and Frederic Sharf.

Illustrated Japanese Publications of Prints

10. KONISHI Shirō, Nishikie—Bakumatsu Meiji no Rekishi [Woodcuts—A History of the Bakumatsu and Meiji Periods], 12 volumes (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1977). This lively, large format, full-color collection of “brocade pictures” (nishikie) depicting current events between 1853 and 1912 includes volumes devoted to the Sino-Japanese War (vol. 11) and Russo-Japanese War (volume 12).

11. ASAI Yūsuke, ed. Kinsei nishikie Sesōshi [A History of Modern Times through Woodcuts], 8 volumes (Tokyo, 1935-36). This old collection, with extensive black-and-white reproductions, is a standard reference source.

Illustrated Collections

12. H.W. Wilson, Japan’s Fight for Freedom: The Story of the War Between Russia and Japan, 3 volumes (London: Amalgamated Press, 1904-1906). This exceptionally lavish, large-format British publication totals 1,444 glossy pages and includes hundreds of photographs as well as excellent black-and-white reproductions of sketches and paintings by foreign artists. This is surely the best single overview of the type of war photography and serious war art that appeared regularly in British periodicals like the Illustrated London News. As the title indicates, the overall approach is favorable to Japan.

13. James H. Hare, ed., A Photographic Record of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Collier & Son, 1905). This glossy, large-format, 256-page volume includes photographs by a number of cameramen (as well as a brief commentary on “The Battle of the Sea of Japan” by the influential American naval strategist A. T. Mahan). In comprehensiveness as well as clarity of the reproductions, this is an outstanding sample of the war photography of the times. (The same publisher produced another large-format volume on the war—titled The Russo-Japanese War: A Photographic and Descriptive Review of the Great Conflict in the Far East—that includes many of the same images, is also of considerable interest, but is of lesser technical quality.)

14. Nishi-Ro Sensō [The Russo-Japanese War] (Tokyo: Yomiuri Shimbunsha, 1974). This volume reproduces the distinctive and elegantly tinted photos of the American photographer Burton Holmes, whose war work deserves to be better known.

15. Shashin: Meiji no Sensō [Photos: Wars of the Meiji Period], Ozawa Kenji, ed. (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 2001). This thick volume (270 pages) contains numerous black-and-white reproductions of photos of the Seinan civil war (1877) and the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars.

16. A Century of Japanese Photography, John W. Dower, ed. (Pantheon, 1980). This is an English-language adaptation of an outstanding collection of prewar Japanese photography edited by the Japan Photographers Association and originally published under the title Nihon Shashin Shi, 1840-1945 (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1971). Three plates depict the Sino-Japanese War (plates 169-71) and twelve are photos from the Russo-Japanese War (plates 172-83). The latter include several truly classic images.

General Historical Texts

Teachers, students, and anyone else who wishes to pursue the history of Japan’s emergence as a modern nation further will find the following publications particularly useful as both general overviews and reference sources:

17. Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan. This outstanding encyclopedia exists in two editions: (1) a detailed 9-volume version (published in 1983 and containing over 10,000 entries, including extended essays by major scholars); and (2) an abridged and lavishly illustrated two-volume version titled Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia (1993). Anyone seriously interested in Japanese history and culture should have these reference works on hand. For this present web site, see in particular the entries on “Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95” (by Akira Iriye) and “Russo-Japanese War” (by Shumpei Okamoto).

18. Paul H. Clyde & Burton F. Beers. The Far East: A History of Western Impacts and Eastern Responses, 1830-1975, 6th edition (Prentice-Hall, 1975). Originally published in 1948, this standard “diplomatic history” remains a useful reference for sharp analysis as well as basic data.

19. Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present(Oxford, 2003). This survey history by a leading scholar reflects the most recent research on modern Japan. (384 pages).

20. Mikiso Hane, Modern Japan: A Historical Survey, 2nd edition (Westview Press, 1992; originally published in 1982). Hane’s great strength lay in his keen ear for the “voices” of people at all levels of Japanese society. (473 pages).

21. Kenneth B. Pyle, The Making of Modern Japan, 2nd edition (D.C. Heath, 1996). Originally published in 1978, this thoughtful overview has the additional virtue of brevity. (307 pages).

22. Peter Duus, Modern Japan, 2nd edition (Houghton Mifflin, 1998). Originally published in 1976, this is another reliable survey text. (376 pages).

23. Julia Meech-Pekarik, The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization(Tokyo and New York: John Weatherhill, 1986). This is the standard introduction to Meiji prints in English.

Originally published by Visualizing Cultures, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license.