The choices the colonial poor faced.

By William P. Quigley, J.D.

Clinic Professor Emeritus of Law

Loyola University New Orleans

Introduction

“[Those] who would not work must not eat.”1

“[Flor those who Indulge themselves in Idleness, the Express Command of God unto us, is, That we should let them Starve.”2

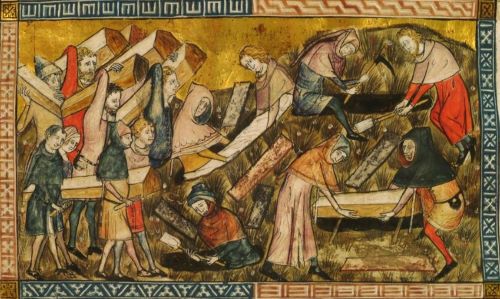

Colonial poor laws have, not surprisingly, helped shape subsequent poor laws of the United States. From the very inception of colonial poor laws, the choice for the poor, with few exceptions, was to work, or starve.

The ability of a poor person to work was the preeminent in determining whether they were worthy of public assistance. Those determined able to work were not eligible for help; people already working were not eligible. Although widows and children in need were given assistance, they also were expected to work. Only those deemed unable to work were considered truly worthy of poor relief. Of course this rule did not apply to slaves, free blacks, and Native Americans.

This Article traces the development of pre-revolutionary American colonial laws for the working and nonworking poor.3 Capturing the essence of colonial poor laws is somewhat like trying to chart the origin of the Mississippi. There are numerous sources, and any article describing this topic can only briefly identify the major tributaries.4 Consequently, this Article sketches out the major themes and developments of colonial poor laws on the Atlantic seaboard.5

The English colonization of America was undertaken for property and profit. Poverty and idleness had no place in the push for colonization; in fact it was considered sinful. The poor laws of England, and their principles, were adopted and adapted for colonial life. Local communities supported their poor who were unable to work. Those considered able to work were denied help and put to work. Indigents arriving from other places were turned away. Yet there remained many who worked very hard and were still poor. These people included indentured servants, apprenticed children, African slaves, and colonial debtors. While colonial law regulated the working poor, they were refused assistance. This Article reviews the above-described laws; and draws conclusions about the choices the colonial poor faced.

English Colonization of America

In 1493, a papal pronouncement declared that America was to be divided between Spain and Portugal. Despite this, English King Henry VII, in 1497, commissioned John Cabot to seek new land. After Cabot’s landing in America, the continent was claimed for England.6

The settlement of the American colonies by the English occurred for several reasons.7 There were settlements by trading companies like the Virginia Company, as well as settlements by those searching for religious freedom, such as the Pilgrims and those who settled Rhode Island. Colonial settlement was also undertaken by proprietors, or commercial profit-based organizations.

The trade companies gained their first foothold in 1607. Captain Christopher Newport, hired by the Virginia Company of London, landed three ships, the Sarah Constant, the Goodspeed, and the Discovery, at the site now called Jamestown, Virginia.8 Shortly thereafter, Captain John Smith mounted explorations for the Virginia Company and later the Plymouth Company, exploring New England.9 The Jamestown experience helped profoundly shape and reinforce the Puritan work ethic which had such great influence on the subsequent development of colonial poor laws. Jamestown was a traumatic experience, a failure for the Virginia company, and a tragedy for those involved. The failure was widely blamed on the lack of energetic work by the early settlers who would, according to John Smith, rather complain, curse, and despair than work.10 As a result, the necessity for everyone to labor was underscored.

The search for religious freedom also motivated English settlers.11 These religious influences put great emphasis on industry and the avoidance of idleness.12 The proprietary settlements of the middle and southern colonies were more feudal and manorial in nature than the settled colonies, mainly because their owners were a product of that culture in England.13 For example, in 1632, the Maryland charter, comprising between ten and twelve million acres, was carved out of the territory previously granted to the Virginia Company. This land was granted to the family of George Calvert, who was called Lord Baltimore.14 This created large agricultural enterprises that needed many, many workers in order to turn a profit.

Practical, religious, and commercial forces all combined to place great emphasis on the work ethos in the colonies. The colonial commitment to work impacted every phase of colonial life, including the colonial poor laws.

The Poor in Colonial America

The poor people in early America were much like the impoverished of today. The indigent included mothers who had been abandoned or widowed, the sick, disabled, elderly, and mentally ill. There were also those considered lazy and criminal. Of those who came voluntarily to America, most were of modest means, if not destitute.15 In fact the desire for land and an opportunity to make a home for a family was a large reason for the migration of so many from England, where opportunities were scarce.16

For example, a very large part of the population who originally settled in Virginia were poor people from England: “The chief dependence for a supply of labor in the seventeenth century was this large body of unemployed in England-the poor, paupers, vagabonds, and convicts, who were transported to Virginia mainly through the agency of the indentured servant system.17 There were increasing numbers of illegitimate children in Virginia as more indentured servants arrived.18 Children of these formerly indentured servants, legitimate and illegitimate, were too frequently left behind when the servant was free to leave.19 The care of orphans was also the subject of Virginia poor laws.20 Virginia statutes also evidenced the need to care for the elderly and the sick and lame.21 And, from the earliest dates, there are reports of people who were described as “vagrant, idle and dissolute persons.22 Statutes in Connecticut23 and South Carolina24 also evidence growing numbers of poor people in the colonies.

Urban areas were the hardest hit by poverty.25 As the colonial population grew and the availability of land decreased, and as war booms and peacetime recessions left widows, disabled soldiers, and their families adrift, the cities felt the press of poverty.26 It was the seaport towns where widows and orphans journeyed to seek help, and where the newly arrived immigrants began their lives in America. As a result, the large pool of labor in these towns, and the fluctuating employment patterns, did not create a hospitable environment for the poor.27

Women made up a large proportion of the colonial poor, in some towns one-third to one-half of the paupers.28 In the 1740 census of Boston, 30% of the married women were widows, most as a result of fatalities of war.29 Additionally, the colonies had their share of the poor who were sick, as well as the physically and mentally disabled.30 These indigents included people expelled from other countries, like the Acadians, who came to the colonies and needed assistance to get started again.31

People who had skills were not usually impoverished. In fact, periodic labor shortages greatly favored the willing and able worker.32 But as the colonies matured, unemployment became a greater problem. While there was a high demand for labor in the colonies’ early years, the middle and later 1700s suffered periods of widespread unemployment caused by extended business slumps.33 For example, in Massachusetts in the 1700s, poverty became more pervasive as the population of the colony expanded, while wars, price inflation, and flat wages took their toll.34 The number of transients increased as people moved from town to town looking for work.35

Another category of the “working” poor consisted of the slaves. The largest number of settlers in America prior to the revolution were African slaves, nearly one million people.36 Though primarily settled in the southem colonies, slavery was present throughout the colonies, with significant numbers in places like Philadelphia and Boston.37

Poverty in the colonies stood side by side with wealth. There is evidence that the long range trend in the cities of the colonies was toward greater concentration of wealth. Over the course of the eighteenth century, the wealth of the top 5% of cities’ richest families grew from thirty-three to 55%; the same statistics are true for Philadelphia.38 Although overall wealth increased in the pre-revolutionary cities, it is clear that not everyone enjoyed the benefits.39

By the late 1700s poverty in the colonies was growing: Boston in 1757 reported supporting 1000 people with some form of poor relief; the poverty rate in New York quadrupled; and in Philadelphia the poverty rate was also surging.40 By the eve of the Revolution, one-fifth of all households were faced with poverty.41 The presence of this widespread poverty probably helped fuel dissatisfaction with the colonial system and revolutionary fervor.42 Colonial poor laws were enacted to assist and regulate this diverse group of poor people.

Roots of Poor Laws in the English Colonies

Overview

Colonial poor laws have English lineage, are supported by Puritan theology’ and were administered by public-private partnerships. All three of these influences are discussed in the following section.

Influence of English Poor Laws in the American Colonies

English Poor Laws were the single most important source for the development of early American legislation addressing poverty.43 While individual economic and social circumstances shaped each colony’s response to its poor, the English poor laws were usually the frame of reference for local action.44 These laws are characterized by their provisions for direct aid for the unemployable; work, or imprisonment, for those able to work; and an emphasis on local administration.45 As early as 1647, Rhode Island proclaimed that the core of their poor relief system was to be based on English poor laws. Maryland cited the English statute in their own: “It is agreed and ordered by this present assembly, that each towne shall provide carefully for the relief of the poor, to maintain the impotent, and to employ the able, and shall appoint an overseer for the same purpose.46 A 1661 New Plymouth statute provided that vagabonds should be punished and removed “according to the laws of England”47 A 1672 Virginia act ordered the Virginia justices of the peace to “put the lawes of England against vagrant, idle and dissolute persons into strict execution.”48

Influence of Puritan Ideology on Poor Laws

Puritan influence was strongest in the northern colonies, but it impacted all colonial law, including the poor laws.49 “The attitude in the colonies toward wealth, property, and poverty reflected the great emphasis on individual enterprise. The influence of the Puritan ideology was widespread. Poverty, like wealth, demonstrated God’s hand, and while riches were proof of goodness and selection, insufficiency was evidence of evil and rejection.”50 According to the Puritans, assistance to those in need was part of the religious responsibility of the wealthier colonists-divine order made some people rich and powerful while, others were poor and dependent.51 Indeed poverty was not even a necessary evil but an opportunity for the rich to help.52 While church teachings recognized a religious responsibility for aiding the poor, this did not apply if the impoverished were considered idle, or were from outside the community.53

The Puritan work ethic was shaped in part by the experience at Jamestown. As previously noted, the Jamestown failure was blamed on the habits of the settlers themselves.54 Frustrated with the lack of work in the settlement, Captain John Smith declared that those who would not work, would not eat.55 Smith, in a gesture one historian “suspects would only have been made in English America,” instituted a “President’s order for the drones.”56 The “drones” of the colony would have to work at least as hard as Smith himself, or be banished: “The sicke shal not starve, but equally share of all our labours, and every one that gathereth not every day as much as I doe, the next daie shall be set beyond the river, and for ever bee banished from the fort, and live there or starve.”57 The work or starve edict of Jamestown was entirely consistent with Puritan thought.

The prime example of Puritan moral thought is Cotton Mather. Mather preached that there was a responsibility to care for the unemployable. Mather himself actively engaged in direct assistance to the poor, and encouraged and recruited others to do good works as well.58 However, Mather is best known for his directives concerning work and poverty. For example: “The poor that can’t work are objects of your liberality. But the poor that can work and won’t, the best liberality to them is to make them.”59 Or, more famously: “[Flor those who Indulge themselves in Idleness, the Express Command of God unto us, is, That we should let them Starve.”60 The Puritan ethic stressed helping those who had fallen on hard’ times by virtue of disease or disability, while the same ethic suggested sterner medicine for those who were impoverished by their own lack of industry.61

Viewed in its best light, the Puritan concept of charity consisted not of giving alms to the needy, but in providing opportunity for the needy to secure their own needs by work. Viewed in its worst light, the Puritan concept of charity assumed no responsibility at all for the’ needy, rather choosing to blame and shame the needy for their individual failings and weaknesses.62

Public and Private Local Partnership for Care of the Poor

By necessity, assistance for the poor became a joint public-private partnership in the colonies.63 The most prominent authority on American philanthropy notes:

The line between public and private responsibility was not sharply drawn. In seasons of distress, overseers of the poor frequently called on the churches for special collections of alms, and throughout the colonial period giving or bequeathing property to public authorities for charitable purposes remained a favorite form of philanthropy. Friendly societies organized along national, occupational, or religious lines relieved public officials of the necessity of caring for some of the poor by supplying mutual aid to members and dispensing charity to certain categories of beneficiaries.64

Colonization does not traditionally include within its purposes a spirit of social responsibility, and the English colonization of America was no exception.65 However, there was a necessary spirit of communal support in the colonies, since few colonists were so affluent that they could avoid reliance on their neighbors.66 The first private assistance given to needy colonists was provided by the Indians who generously assisted Columbus and later, other Europeans.67

In the early colonies, the responsibility for the poor rested on those private parties who brought the poor to the colonies in the first place.68 Families helped their own. The poor assistance that existed consisted of mutual aid-neighbors helping neighbors.69

Poor relief was accepted as a prime responsibility of religious groups in many parts of the United States. Private church aid existed parallel to the systems later created and maintained by the public authorities.70 The Quakers in Pennsylvania believed wealth was given by God for personal and public good; these attitudes influenced later humanitarian efforts.71 The Great Awakening, which began in the late 1720s, brought renewed attention to the plight of the poor, and fostered more humane attitudes towards the needy.72

Virginia churches followed the English method of parish assistance to those in need, supported by a tithe levied on all their members.73 In the Anglican South, private charitable efforts were more effective than in the Calvinist North. The large Southern landowners, “imbued with a spirit of noblesse oblige and trying to maintain a social system not unlike that of feudalism, felt that aiding the needy was more a personal than a civic responsibility.”74

The first phase of all poor relief, public or private, emphasized local assistance. As in England, the preference was for local responsibility for the poor, local taxation for public relief, and local administration of the assistance given.

After some time, however, reliance on the local system began to break down as some localities, particularly urban areas, supported larger numbers of poor than others. Town resources became over-stressed, as the poor from across the oceans poured in. These included widows, orphans, people expelled from smaller communities, and those who could not survive on the frontier.75

Local efforts required colony-wide assistance. By the early 1700s, the Massachusetts colonial treasury, by way of the General Court, was authorized to reimburse local communities for some of their relief for the unsettled poor.76 A 1701 statute directed that recently arrived, disabled poor were to be supported by the provincial treasury-provided that they had previously been Massachusetts residents, or had fallen ill on their voyage.77 The same law extended the residency period for settlement purposes to one year.78 The breakdown of localism helped expand assistance to the needy.79

Colonial Poor Relief Legislation

Overview

The poor laws adopted by each of the individual colonies were tailored to individual economic and cultural needs. The laws emphasized local responsibility for the poor, and intergenerational family responsibility. Responsibility for the care of the poor was also placed on private parties, such as the ship masters who brought them to the locale. Forced work or imprisonment was instituted. Children of the poor were removed from their families and placed into apprenticeships. Additionally, strict residency requirements, called settlement laws, were instituted to keep the poor from other communities from settling in a particular locale.

There was no systematic, linear development of the poor laws in the colonies. Rather, as this section illustrates, the colonies used different methods of providing poor relief. Some used town meetings, while others appointed overseers. Other colonies based relief on the town or county unit or the church parish. While a comprehensive overview of the development of each colony’s poor law exceeds the scope of this Article, an examination of representative poor laws from the colonies is important to understand the overall development of colonial legislation.80

New England Colonies

The legal institutions of the New England colonies of New Plymouth, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire shared many common characteristics.81 The most influential of these was Massachusetts.82

In 1639, the Massachusetts Bay Colony83 enacted procedures for deciding how local poor relief and settlement were to be administered:

[T]he court, or any two magistrates out of court, shall have the power to determine all differences about a lawful settling and providing for poor persons, and shall have power to dispose of all unsettled persons into such towns as they shall judge to be most fit for the maintenance of such persons and families and the most ease of the country.84

Other early Massachusetts poor laws authorized local communities to put idle adults and children to work.85 The laws also instituted a three month residency requirement to be satisfied before anyone was entitled to poor relief.86

New Plymouth, the oldest New England settlement, greatly influenced Massachusetts poor law.87 In 1642, the Plymouth Colony adopted provisions of the English poor laws acknowledging responsibility for the indigent, and made local taxpayers responsible for their support: “That every township shall make competent provision for the maintenance of their poor according as they shall find most convenient and suitable for themselves by an order and general agreement in a public town meeting.88 Other statutes required families and plantation owners to care for their indigent former servants, or “outlawed” idleness.89 Apprenticeships for children of families on relief were created.90 With these statutes in place, almost every community in the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies provided a system of relief for their poor.91

The major legislative contribution of Massachusetts was the 1692-1693 revision of laws, which occurred after the new provincial charter was promulgated in 1691. The charter absorbed New Plymouth into Massachusetts.92 This revision contained many of the major principles of

poor law that operated for quite some time, including the clear responsibility of family members for the support of their own impoverished relatives93 and the authorization of town officials to take “effectual care” that all idle adults and children be put to work.94 The revision assessed taxes on all inhabitants and residents “for the maintenance of the Ministry, Schools, and the Poor,”95 and provided authority for the apprenticing of poor children.96 The laws delegated responsibility for the sick and lame,97 and required poor seeking relief to have been residents of the town for the preceding three months.98

Thus, Massachusetts became the leader of the New England colonies in poor relief legislation, and their poor laws were copied by other New England colonies.99 The Massachusetts poor laws formed the pattern of legislation followed by Connecticut and New Hampshire.100

Middle Colonies

The area covered by the grant to the Duke of York was called the Middle Colonies. This included the colonies of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania was the pioneer of the Middle Colonies in developing legislation regulating the poor.101 Delaware and New Jersey mainly followed Pennsylvania’s lead.102 New York followed both English and Dutch law, as well as New Jersey and Delaware statutes in creating its colonial poor laws.103

Pennsylvania, including what is now Delaware,104 was under the proprietorship of the Duke of York until it was ceded to William Penn in 1681.105 Under Penn, the 1682 laws for the colony provided:

That if any person or persons shall fall into decay and poverty, and not be able to maintain themselves and children, with their honest endeavors, or shall die and leave poor orphans, that upon complaint to the next justices of the peace of the same county, the said justices. . . shall make provision for them … till the next county court, and that then care be taken for their future comfortable subsistence.106

In 1705, Pennsylvania passed a comprehensive act for the relief of the poor, based largely on contemporary English poor law, which put primary responsibility for relief of the poor on their grandparents, parents, and children.107 A 1718 act created the Pennsylvania residency requirements, or “law of settlement,” again largely based on English law.108 The settlement, law was modified in 1735 by introducing the certificate system. This system required people who sought to move to another town to provide a signed certificate from the officials in the town they were moving from, guaranteeing that any prospective poor relief would be reimbursed by the previous town.109

In 1771, Pennsylvania completely revised their poor laws. These laws are significant because they were later used as the laws of the Northwest territory. The 1771 Act authorized the overseer system, construction and operation of Houses of Employment, and boarding out the poor. The law also provided for the apprenticing of poor children, the law of settlement, and the reciprocal three-generation duty of support. The law further authorized the seizure of assets of fathers who abandoned their wives and children.110

Southern Colonies

The Southern Colonies of Virginia, Maryland, and South Carolina were socially and institutionally organized quite differently from the New England colonies. II Virginia was a royal province after 1623, and Maryland and Carolina were “proprietary colonies with particular feudal rights in the owners.”112 In these colonies, the county, not the town, was the most important unit of government.113

While the poor laws of the Southern colonies were not unlike those of the other colonies, the actual administration of the laws took on a distinctly regional flavor.114 The Southern colonies did not institutionally respond to poverty like their Northern neighbors, but relied on local relief.115

Virginia followed the English parish system of poor relief.116 After 1641, the colony was divided into parishes, whose governing body was the vestry. The vestry had the duty of administering the poor laws.117 As in England, while the duty of providing for the poor was placed on the local parish, the enforcement of the poor laws was the duty of the justices of the peace.118 Virginia’s poor laws in the 1600s authorized relief from tax payments for the settled poor who were unable to work due to “sickness, lameness, or age.”119 They also provided for compulsory labor or apprenticeship for poor children,120 as well as the suppression of vagrants and forced work for the idle.121 Later laws instituted a one-year residency requirement to become eligible for services.122

Carolina was divided into provinces. The northern section became the province of North Carolina,123 the southern section was divided into counties.124 In 1694, South Carolina established a system for relief of the poor based on the responsibility of the provinces.125 This law, amended in 1695, authorized local commissioners to spend provincial money to assist sick, lame, old, blind, or other impotent persons and provided authorization to apprentice poor children and to put the nonworking poor to work.126

South Carolina’s poor law of 1712 was the first comprehensive poor law enacted in the southern colonies.127 The law set up a parish-based system of overseers of the poor.128 There was a three-month settlement period and an administrative structure for removal of the unsettled poor.129 Three generation family responsibility for the poor was continued.130 Poor children were allowed to be bound out as apprentices.131

Maryland had no state-wide poor law until 1768.132 Prior to that time, the counties assumed responsibility for the poor.133 The 1768 law acknowledged a growing population of people in poverty.134 The law called for the appointment of local trustees to supervise and regulate care for the poor,135 and authorized the construction and administration of houses for the poor, which were divided into almshouses and workhouses.136 The law provided for the commitment of a man or woman to the workhouse for a period of up to three months if they were judged disorderly and “likely to become chargeable to the said county.”137 The law also directed: (1) the appointment by the trustees of a paid overseer to administer the day-to-day activities of regulating the poor,138 (2) the removal of poor persons from the county,139 (3) all residents of the almshouse or workhouse to wear “a large Roman P” made from red or blue cloth on their right sleeve, under pain of suspension of relief, twenty lashes or hard labor,140 and, (4) the taxation of residents to pay for these activities.141

Poor Laws and Those Unable to Work

Overview

All colonial poor laws acknowledged a public responsibility to provide for the impoverished neighbor who was unable to work. This principle, borrowed from English law, became a cornerstone of colonial and, later, American tradition.142

Colonial poor laws continued the English poor law concept of classifying the poor based on their ability to work. Relief was provided only to the “worthy poor,” i.e. those unable, by reason of some infirmity, to work.143 Those in need who were able to work were rarely provided assistance under the colonial poor laws. In the colonies, as in England, voluntary idleness was regarded as a sin and a crime.144 The able-bodied unemployed were either bound out as indentured servants, whipped and run out of town, or jailed.145

The needy were categorized according to two systems. The first involved a determination of their ability to work. The second divided the needy into the categories of neighbor or stranger.146 In this latter classification system, poor people were divided into four categories: (1) neighbors in need who could not work, (2) neighbors in need who were able to work, (3) strangers in need who could not work, and (4) strangers in need who were able to work. Not surprisingly, aid was provided only to the neighbor in need who was unable to work.

This section will discuss eligibility for assistance under colonial poor laws for those unable to work. This category included the infirm, mentally ill, widows, women with children, and children. Following sections will address those able to work, and the treatment of strangers.

The Infirm, the Impotent, and the Aged

The colonial poor laws acknowledged a public responsibility to provide for the impoverished neighbor who was impotent or sick, if no one else could so provide. Aged neighbors were also assisted, but only to the: extent that they were unable to support themselves.

English poor laws, dating back to 1388, differentiated between beggars who were “impotent”, or unable to work, and those who were able-bodied. 147 “[W]omen great with child, and men and women in extreme sickness” who were caught begging were given more lenient punishments.148 “[Plersons being impotent, and above the age of [sixty] years” were ordered to be given special consideration by local authorities.149

From the outset, the colonists showed great compassion for the sick and impotent. Recall the settlement of Jamestown, when Captain John Smith pledged: “The sicke shal not starve, but equally share of all our labours . . . .150 This compassion and support was built into the colonial poor laws. In 1647, Rhode Island mandated that each town provide for the poor and “maintain the impotent.”151 South Carolina authorized commissioners for the poor to assist the sick, lame, old, blind, or other impotent persons.152 Likewise, Virginia’s earliest poor laws authorized tax relief for the settled poor who were unable to work due to “sickness, lameness, or age.”153

Age, by itself, offered no entitlement to poor relief. However, when combined with poverty and an inability to work, advanced years usually qualified one for assistance. For example, older persons in North Carolina were provided the opportunity to apply for relief from taxes on a case-bycase basis. The records indicate that poor persons over 60 were usually granted tax exemptions.154

The Mentally Ill

Mental illness was addressed by the civil authorities, not by medical assistance.155

Occasionally, in the course of the colonial period, some assemblies passed laws for a special group like the insane. But again it was dependency and not any trait unique to the disease that concerned them. From their perspective, insanity was really no different from any other disability; its victim, unable to support himself, took his place as one more among the needy. The lunatic came to public attention not as someone afflicted with delusions or fears, but as someone suffering from poverty.156

Most colonial laws involving the nonpoor mentally ill concerned the management of their property, rather than the’management of the person.157 Massachusetts instituted a statute in 1676 governing the insane or “distracted persons” in the community:

Whereas there are distracted persons in some towns that are unruly, whereby not only the families wherein they are, but others suffer much damage by them, it is ordered by this Court that the Selectmen in all towns where such persons are, are hereby empowered and enjoined to take care of all such persons that they do not damnify others.158

In 1693, another Massachusetts law “for the relief of idiots and distracted persons” was adopted.159 This law authorized “selectmen,” or overseers of the poor, to assume responsibility “for the relief, support and safety of such impotent or distracted persons” and to sell any property of persons that could supplement their support.160

Nonviolent mentally ill who were. supported by public authorities were, like other dependent poor, frequently given food and shelter in private homes of people who were reimbursed for their troubles.161 Violent mentally ill were imprisoned either in the public jail, or in kennel-like “houses” specially constructed for them.162

Mentally ill strangers who arrived in town were “warned out,” driven away with whips, or banished from the town in accordance with the law of settlement.163 During the Salem Witchcraft Trials, the mentally ill were “hanged, imprisoned, tortured, and otherwise persecuted as agents of Satan.”164

In the 1700s, the mentally ill received housing in the institutions that emerged to house the poor. A 1727 Connecticut act authorized the commitment in the local Houses of Correction of “persons under distraction and unfit to go at large, whose friends do not take care for their safe confinement.”165 An institution in New York put the mildly insane to work spinning flax and knitting, and confined those who were more afflicted in special dungeons located in another part of the institution.166 There were other efforts to separately house the sick and mentally ill away from the other poor, including a notable plan by a Philadelphia group including Benjamin Franklin.167 For the colonial mentally ill, the best they could hope for was indifference-the other alternative was usually confinement.168

Widows and Women with Children

Widows and women with children were not considered eligible for assistance based on need alone. Poor women were expected to work, unless sick or disabled.169 Widows and their children were also not exempt from the expectation that they work for their sustenance. Indeed, according to a prominent Boston preacher, Samuel Cooper, money given to nonworking widows and their children, was “worse than Lost.”170

Needy women determined undeserving of assistance were auctioned off by their town to the lowest bidder, in an arrangement whereby the poor woman would exchange domestic labor for food and board.171

Children

While younger children were assisted by the poor laws, needy children over twelve, even orphans, were not usually exempted from the general expectation that all those in poverty should work. Poor children, like other poor, were first the responsibility of their parents and grandparents. Only if the family failed to care for them did they become the responsibility of the system of poor relief.172

For poor children, the primary method of assistance was to place them outside the family in apprenticeships. This practice helped fill the need for labor, and reduced the public burden. Colonial apprenticeship was patterned on the English poor laws of 1601 which authorized overseers of the poor to bind out the children of paupers.173 For this practice, authorities created three classes of children: poor children, orphans, and illegitimates.174 Apprenticeship assigned these children to a person who would provide room and board, and instruction in a trade, in return for labor.175 This system included girls as well. The children usually apprenticed until they reached the age of twenty-one.176

As an example of how ingrained child apprenticeship was, in 1619, London sent one hundred orphaned children to Virginia-to serve as apprentices.177 They were so well received that Virginia petitioned for another hundred the next spring!178 A 1646 Virginia statute ordered each county commissioner to send two poor children to the public flaxhouse in James City for compulsory labor.179 A 1688 act ordered the county court to take “poore children from indigent parents to worke in those houses.”180 And in 1672, because of an increase in “vagabonds, idle and dissolute persons,” Virginia county courts were authorized to bind out all poor children-boys until the age of twenty-one, girls until they reached eighteen.181

Other states followed suit. Connecticut authorized the taking of children from poor families to be placed with other families, “where they may be better brought up and provided for.”‘182 In 1712, South Carolina authorized parishes, the local units caring for the poor, to bind out poor children as apprentices. Parental permission was not necessary; permission of the local church vestry sufficed.183 Rhode Island enacted a statute in 1740 authorizing town councils to bind out not only poor children, but children who were thought likely to need assistance in the future.184 Apprenticeship of poor children continued throughout the colonial period. As late as 1771, Pennsylvania authorized children with deceased parents, or with parents “found unable to maintain them,” to be sent to the House of Employment.185

Methods of Providing for the Poor

In the early colonial years, the most common way of providing relief for the poor was the placement of poor people in private homes of people in the community where their food and shelter needs would be satisfied at public expense.186 As the population of the colonies increased, the number of people in poverty increased, and colonial authorities expanded the ways in which they provided assistance.

The first method of assistance was always to look to the family. Family members of the poor were the primary group responsible for their support, and only if they did not provide support did the poor relief system begin. As Pennsylvania law states:

[T]he father and grand-father, and the mother and grand-mother, and the children of every poor, old, blind, lame and impotent person, or other poor person not able to work, being of sufficient ability, shall, at their own charge relieve and maintain every such poor person …. 187

If the family was unable to assist, the colonies utilized one of four basic methods of assisting the nonworking poor: (1) a contract between the town and a provider; (2) auctioning off the care for the needy person to the lowest bidder; (3) requiring the needy to move into poorhouses or other institutions and there to receive assistance (often called indoor relief); or, (4) giving assistance directly to the poor and allowing them to live wherever they pleased (often called outdoor relief).188

Overseers of the poor came into existence as regulation of the poor became more extensive. Duties of the overseers included deciding who was eligible for assistance, what kind of assistance should be given, supervision of the institutions housing the poor, and accounting for the public and private funds raised for assistance. The overseer was directly responsible for the day-to-day operation of the poor laws and decisions about how the poor were treated. Appeals from the decisions of the overseers were to the justices of the peace.189 Overseer of the poor was not a sought-after position; citizens were not always willing to serve as overseers and chose to pay the fines for refusal rather than serve, occasioning increases in the fines for not serving.190

Housing the poor in institutions was not done in the earliest colonial years. However, as towns grew and the numbers of poor people rose, many communities looked for alternatives to family care. Consequently, almshouses, workhouses, and houses of correction began to sprout up, first in cities and soon in towns.191

Theoretically, there was a difference between an almshouse or a poorhouse and a workhouse or house of correction. The poorhouse or almshouse was to house the “worthy” poor, those unable to work. The workhouse, sometimes called the house of correction or house of employment, was a place to take the “unworthy” poor, like vagrants, and to force the idle to labor. This theoretical division between institutions was not always followed, resulting in mixed institutions. For example, Maryland, in 1768, called for the erection and administration of houses for the poor, which were to be divided into two parts, one called an almshouse and another called the workhouse. The poor were to go into the almshouse, while the vagrants, beggars, and vagabonds were to be lodged in the workhouse.192

The appearance of the almshouse or workhouse “represented a transition between the custodial family of the countryside and the truly largescale institutions that emerged in early nineteenth century America.”193 These institutions were never the primary method of providing for the poor during the colonial period; their presence was still minor compared both to their presence in England at the same time, and to later stages of American regulation of the poor.194

In the seventeenth century, there were but a few such institutions. Plymouth Colony passed a law in 1658 creating a house of correction where vagrants, the idle, rebellious children, and stubborn servants were to be put to work.195 Boston built a workhouse or almshouse with private funds in the 1660, and other communities followed.196

The operation of workhouses can be determined by reviewing a 1699 Massachusetts statute which called for every county to erect, at taxpayers’ expense, a House of Correction for “keeping, correcting and setting to work of rogues, vagabonds, common beggars, and other lewd, idle, and disorderly persons.”197 The concurrence of two justices of the peace authorized anyone “being able of body, that live idly or disorderly, misspend their time, or that go about begging, or receive alms from the town” to be sent to the workhouse.198 Materials for work were provided and residents of the house were forced to work. If they refused they could be punished by food deprivation, shackles, and “moderate whipping, not to exceed ten stripes at once … until they be reeducated to better order.”199 Those who were determined able to work were to pay for their housing out of their wages. The housing costs for “stubborn children or servants” were to be paid by their parents or masters.200 The mixed nature of these institutions can be seen from the provision in the law that those unable to work were to be housed at town expense.201

In the 1700s the numbers of these colonial institutions increased. Pennsylvania, in 1705, provided for prison workhouses for “felons, thieves, va,grants, and loose and idle persons” to be built in each county.202 In 1727 Connecticut created workhouses for those determined able to work.203 Philadelphia built a workhouse in 1731, and New York did the same in 1736.204 Boston constructed a separate workhouse for the able-bodied poor in 1735.205

Requiring the poor who sought help to move into public institutions was partly a reflection of the thought, already prevalent in England and in the colonies, that poor people needed to be shamed into self-improvement by stigmatization.206

Another manifestation of this belief was the requirement that poor people wear badges in public.207 New York City required the badging of paupers in 1707.208 Pennsylvania compelled the poor to wear a badge with the letter P on it.209 New Jersey required paupers to wear a large P on their shoulder, plus another letter designating the name of the city or county in which they resided.210 The 1768 Maryland. poor law required all residents of almshouses or workhouses to wear a large Roman P made from red or blue cloth on their right sleeve. A violator of this law risked suspension of relief, up to twenty lashes, or a maximum of twenty-one days of hard labor.211 Badging was a reflection of common moral assumptions about the poor. If people remained poor it was because of their own bad decisions, which squandered their God-given opportunity.212

Colonial Law of Settlement: Limiting Strangers

Conventional wisdom suggests the colonies were a haven for strangers and immigrants, a place where a person’s past or purse did not make a difference, and anyone could start over with a clean slate. Unfortunately, this was not at all the case. There was little geographic mobility for the colonial poor. People who were poor but new to the area were forcefully instructed to return to where they came from and subject to jail if they disobeyed their order of banishment.

The colonies passed statutes instituting the English law of settlement and removal, whereby localities were only responsible for taking care of their own poor, not newly arrived strangers.213 These laws remained for centuries.214 The colonies did not think they could afford to welcome strangers who may later turn out to be either economically unproductive or socially nonconforming.215

Recall that colonial poor laws classified poor people in two major ways: whether the poor could work or not; and whether the poor person was a neighbor or a stranger.216 Only neighbors who were unable to work were assisted. The settlement laws determined who was neighbor and who was stranger. As a result, newly arrived poor people were in immediate conflict with local officials. Disputes were resolved by the justices of the peace.217

If an individual refused to leave they were forcibly removed by the constable in a process called “warning out” or banishment.218 The report of the “warning out” by the constable was filed with the justices of the peace.219 If transients reappeared they could be prosecuted as vagabonds, subject to internment in houses of correction or workhouses.220

Massachusetts law illustrates the development of the law of settlement in the New England and Middle colonies. In 1636 in Boston, residents were not allowed to entertain strangers in their homes for more than 2 weeks without permission.221 In 1637, the General Court of Massachusetts ordered that no town or person could “receive any stranger” who intended to reside for more than three weeks without authorization of the court or two magistrates.222

In 1655, the Massachusetts Bay Colony passed the first settlement law for an entire colony:

[S]uch persons as shall be brought into any such town without the consent and allowance of the prudential men, shall not be chargeable to the towns where they dwell, but, if necessity require, shall be relieved and maintained by those that were the cause of their coming in, of Whom the town or selectmen are hereby empowered to require security at their entrance, or else forbid them entertainment.223

This was amended in 1659 to incorporate a three-month residency rule.224

The 1701 law extended the residency period for settlement purposes to one year.225 The law made it clear that any person who returned after being duly warned out was to be prosecuted as a vagabond.226 Throughout the 1700s, Boston’s Overseers of the Poor “warned out of the city hundreds of sick, weary, and hungry souls who tramped the roads into the city in the eighteenth century.227 The one-year settlement period lasted in Massachusetts until 1767, when the 1655 rule was reinstated.228

The same 1701 Massachusetts statute also addressed the situation of those poor people who arrived in the colony by ship.229 The master of every ship arriving in every port of the colony was ordered under pain of fine to provide the town leaders with a handwritten certificate listing the names of every passenger and servant “and their circumstances.”230 The statute directed that if a poor voyager had previously been a Massachusetts resident, they were to be supported by their masters or the provincial treasury.231 But if they were not previous residents of the colony, the shipmaster either had to remove the poor people from the colony within two months, or agree to post security for their care so the town did not have to care for them.232 For example, in November 1719, when the ship Elizabeth arrived in Boston Harbor from Ireland, forty-nine people were warned to leave town immediately because of their poverty.233

Settlement could be achieved in a variety of ways, none of which were available to the unemployed poor. The 1771 Pennsylvania settlement law provided that settlement could be achieved by executing a public office for a year, paying taxes for two years, living in property leased for at least ten pounds annually, owning property and living on it for twelve months, or being an unmarried servant or apprentice for one year.234 Married women were settled wherever their husband was settled, but if the husband’s settlement was not known, settlement was deemed to be the place of their marriage. People arriving from other towns were required to provide a signed certificate from the overseers of their previous settlement indicating they were chargeable to their previous residence if they became needy. People who gained entry by certificate could not gain settlement after twelve months, but only by executing some public annual office.235 Similar laws of settlement were enacted in New Plymouth,236 Rhode Island,237 and New York.238

Settlement and removal were not quite so important in the Southern colonies of Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina until the 18th century. This was so principally for two reasons: First, the area was mostly rural and there were few towns; second, the responsibilities were assumed by the counties rather than the towns.239 For example, in South Carolina in 1712 the time for settlement was three months.240 In Virginia, settlement and removal began in 1727, with a one-year residency requirement.241 Maryland did not even adopt a law of settlement until 1768.242

As the numbers of transients increased dramatically in the eighteenth century, settlement laws increased as an important form of social control.243 Removal and settlement continued throughout the eighteenth century with the expansion of the “certificate” system of enforcement.244

Working Poor in the Colonies

Overview

There were many employed poor people in the colonies. Their legal situation provides a more complete understanding of colonial poor laws. One must first distinguish between the “free” and “unfree” worker. Although free workers were burdened by colonial laws, this Article emphasizes the legal status of the most impoverished workers-the unfree workers. Unfree workers in colonial times included indentured servants, whose liberty (either voluntarily or involuntarily) was constrained for a certain number of years, and slaves.

Free Workers

The law of England was the major source for colonial legislation regulating workers.245 The English law of laborers, artificers, servants, and apprentices had been developed for hundreds of years when adopted. Labor laws in many states, including Virginia, New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, generally followed English labor statutes.246 For example, a 1632 Virginia statute tracked the English Statute of Artificers nearly word for word.247 The English law was not sympathetic to workers. It principally sought to guarantee an adequate supply of labor at a subsistence wage.248

As a result, free workers had many legal limitations, such as laws setting maximum wages.249 Wages were higher than for workers in England, by some estimates as much as 30% to 100% higher.250 Consequently, in the seventeenth century in Massachusetts and New Haven, maximum wage laws were frequently enacted and violators prosecuted.251 Maximum wages were also frequently set by local authorities in the middle and southern colonies in the seventeenth century.252

Even among free laborers was an understanding that their labor could be forced. Free male workers, even when employed, were required to work on public works projects.253 Likewise, as. in England, a laborer was not allowed by law to quit if still working on a task.254 The harshness of these laws should be no surprise considering the exclusion of the working poor from the electoral process. In addition to denying slaves and women the right to vote, the right was denied to the white poor without property in twelve of the thirteen colonies.255 By the time of the American Revolution, only South Carolina allowed propertyless males to vote, and only then if they were taxpayers.256 The rationale was that this population was not “independent” enough, as evidenced by this letter from John Adams:

[V]ery few men who have no property, have any judgment of their own. They talk and vote as they are directed by some man of property, who has attached their minds to his interest …. [They are] to all intents and purposes as much dependent upon others, who will please to feed, clothe, and employ them, as women are upon their husbands, or children on their parents.257

Free people of color were also restricted under colonial laws. While most Africans arrived in America as slaves, many arrived as indentured servants. When their contracts of indenture expired they became farmers, artisans, and landowners.258 However, as the colonial economy became more dependent on slave labor, the colonies instituted slave codes that restricted both slaves and free blacks.259 In Virginia, free people of color were required to register with the town official under pain of imprisonment.260 They were not allowed to purchase Christian indentured servants.261 Pennsylvania imposed restrictions on free blacks in the 1725-1726 statute “An Act for the Better Regulation of Negroes in this Province.262 Section 3 of the Act introduced its restrictions on free negroes with: “[W]hereas it is found by Experience, that free Negroes are an idle, slothful People, and often prove burdensome to the Neighborhood, and afford ill Examples to other Negroes ….”263

Other restrictions required a bond to be posted by slaveowners who chose to free their slaves. Free blacks were prohibited from entertaining any slaves without permission from their masters under fine of five shillings for the first hour and a shilling for every hour thereafter, and failure to pay fines was punished by servitude.264 Impoverished free blacks were generally denied assistance under the colonial poor laws, and left to create their own forms of mutual aid.265 Consequently, voluntary enslavement for periods of up to twenty years was the only way to survive for some.266

All workers were hurt by the colonial laws affecting unfree workers. Employers paid no wages for unfree workers, they only had to expend a one-time purchase price, room, and board. The prevalence of slavery and of compulsory labor by indentured servants provided colonial employers with a cheap and docile labor force, despite the scarcity of labor in a thinly populated country.267

Indentured Servants

Overview

Many came to America as a result of the contractual system of indenture, whereby passage to America was paid in return for the agreement to work for a specified period of years.268 As many as half of the total number of white immigrants to the American colonies may have come over as indentured servants.269 Indentured servants were the principal labor supply for the colonies until they were superseded by slaves in the eighteenth century.270 This system essentially treated working people as commoditiesable to be bought, transported, assigned, leased, and re-sold.271

Indentured servants were generally beyond the scope of the poor laws and left to care for themselves.272 But the indenture system impacted the colonial working poor. Indenture was set up to facilitate the movement of workers from Europe to America and was based on the English system of service in husbandry.273 A major difference between the American and British system was that the American contract of indenture could be sold by the master at any time.274 The practice of indenture was generally harsher in the colonies than in England because beatings and whippings were allowed.275

An example of the pervasiveness of indenture is provided by Virginia, where in the mid 1600s the number of residents who started out as indentured servants ran as high as 75%.276 In Philadelphia, 1838 indentured servants arrived in 1709 alone.277

Indentured servants were of two kinds: those who voluntarily contracted for servitude in return for passage to America or some other monetary reward, and those who were sentenced to involuntarily indentured servant status as punishment for crimes.

Voluntary Indenture

Redemptioners, often called “free-willers,” were white immigrants who, in return for their passage to America, bound themselves as servants for a varying period of years.278 Once the redemptioner arrived in America, traders in servants purchased the indentures from the ship masters and then drove the redemptioner inland to a market where they were sold.279

On April 28, 1772 the brig Patty arrived in Philadelphia with indentured servants for sale. Two days later a notice appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette advertising the sale of about “100 servants & redemptioners, men, women, boys, and girls … whose times are to be disposed of by the master.”280

Families were broken up as husbands and wives were sold to different masters, and children were separated from their parents.281 Once purchased, the indentures were able to be re-sold or assigned to others.282 As Professor Morris notes “The evils of the [indenture] system constituted one of the major scandals of the colonial period.283

In 1620, the Virginia Company sent to its American colony “one hundred servants to be disposed amongst the old Planters.” The Company paid for the cost of passage and the servants were distributed to planters once they reimbursed the cost of passage to the company.284

The main reason for the movement of servants into American colonies was the profit to be made in their transportation and sale.285 There was widespread fraud in the recruitment of people who were sent over to America.286 Transportation to America was often in overcrowded and unsanitary vessels.287

The presence of indentured servants varied by region, with fewer in the New England colonies where farms were smaller, and in the South where slavery was prevalent.288 Curiously, the indentured servant system “flourished most vigorously and lingered longest in Pennsylvania, where it did not disappear until the nineteenth century was well advanced.289 It was estimated that in the early period of the settlement of Pennsylvania 60,000 white servants had been imported into the province in a twenty-year period.290 A 1700 Pennsylvania act prohibited servants from quitting their master’s service without permission. The penalty for infractions was five additional days of service for every one missed, plus damages.291 The same act prohibited assigning servants to others without approval of the justices of the peace, and gave a statutory reward for recovering runaway servants. The act additionally prohibited trading with servants without their master’s permission, under pain of fine if the servant is white and whipping if the servant was black.292

Colonial statutes enforced the contracts of indentured servitude and provided rewards for the return of runaway servants.293 The contracts were usually for a period of two to seven years.294 Indentured servants were not allowed to marry, have children, or carry on a trade without their master’s consent, the punishment for a violation was to lengthen the term of servitude.295

Involuntary Indenture – British Convict Labor

The main involuntary indentures were the thousands of people shipped to America by the English as punishment.296 “During the eighteenth century, transportation became Great Britain’s foremost criminal punishment …. In some jurisdictions over half of all convicted criminals drew sentences of transportation.297 Numerous acts of Parliament punished crimes by transportation to the colonies.298 Criminals, beggars, vagrants, undesirable soldiers, and poor children were shipped to America.299 Most were transported to Maryland and Virginia where they were sold as servants.300

While the number of British convicts shipped to America is hard to determine precisely, it is estimated to be in the range of 50,000-nearly a quarter of the British immigrants to colonial American in the eighteenth century.301 Most of these convicts were young men with minimal labor skills.302

Some have claimed that one of the main motives of English colonization of America was the deportation of undesirables.303 The colonists vigorously objected to this practice to little effect.304 Many colonies passed laws outlawing the importation of convicts305 or forced those who transported in convicts to post bonds.306 However, the transportation and sale of convicts was lucrative, and those profiting from the business were able to persuade English authorities that the colonies overstepped their authority in their attempts to outlaw the importation of convicts.307 Until the revolution, England, to the sharp displeasure of the colonies, continued to sentence English criminals to indentured servitude in the colonies.308

Involuntary Indenture – Colonial Debtors and Prisoners

Another source of involuntary labor in the colonies was the binding out of persons convicted of crimes.309 A 1645 Plymouth law provided for double restitution as punishment for stealing; such restitution could be made either by payment or by servitude.310 Servants already subject to indenture had their term of indenture lengthened for criminal convictions.311

Defaulting debtors were of little use to a labor-poor country if imprisoned. Consequently, laws allowed judgment debtors to be forced into labor for the creditor or, at the creditor’s option, sold at bid.312 The Pennsylvania legislature declared that this debtor servitude was motivated by compassion:

Whereas, in compassion to such unhappy persons, as, by losses and other misfortunes, have been rendered incapable to pay their debts, it is provided by an act of assembly of this government, that if any person be imprisoned for debt, or fines, within this province, and have no sufficient estate to satisfy the same, the debtor shall make satisfaction by servitude, according to judgment of the court …. 313

Scandalously, there are even instances of the children of debtors being sold into service to satisfy the debts of their parents:

If any one contracts debts, and does not or cannot pay them at the appointed time, the best that he has, is taken away from him; but if he has nothing, or not enough, he must go immediately to prison and remain there till some one vouches for him, or till he is sold. This is done whether he has children or not. But if he wishes to be released and has children, such a one is frequently compelled to sell a child. If such a debtor owes only five pounds, or thirty florins, he must serve it for year or longer, and so in proportion to his debt, but if a child of eight, ten, or twelve years of age is given for it, said child must serve until twenty-one years old.314

Slavery

As the majority opinion of Dred Scott v. Sanford stated: “[Alt the time of the Declaration of Independence, and when the Constitution of the United States was framed and adopted … [blacks] had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.315 Slavery harmed every person and institution it touched. There are few more glaring examples of the disparity between law and justice than the extensive laws set up by authorities in colonial England, Spain, and France to authorize and regulate the enslavement of fellow humans.316 The entire legal apparatus was used to establish and enforce the enslavement of blacks.317 This included the poor laws. While treatment of slavery is beyond the scope of this Article, slavery and its interrelation with the poor laws will be briefly reviewed.318

If the evil system of indenture or temporary slavery was “one of the major scandals of the colonial period,319 the system of permanent enslavement was exponentially worse. The entire catalogue of horrors involving the sale of humans as commodities is present in the colonial institution of slavery-sale and re-sale of adults and children, breaking up of families, and physical and sexual abuse.320

Early on, white servitude or indenture was the principal source of labor in the southern British colonies before replacement by slavery. Slaves were initially imported to perform largely unskilled agricultural work, while white indentured servants performed the more skilled trades and crafts.321 Gradually, slaves took over the jobs in the skilled trades and crafts, and the masters ceased importing white indentures all together.322 While the first blacks in Virginia came as indentured servants, by 1661 slavery was institutionalized in Virginia. By the 1700s, slaves were the base of the Virginia labor force.323

As far as slavery and colonial poor laws, there is little to report, for slaves were excluded from the scope of the poor laws altogether. Slaves were considered the property of their masters and, as such, prohibited from receiving aid under most laws.324 Slaves were generally left to care for themselves.325

The intersection of slavery and poverty created some ironic results. For example in Georgia, authorities imposed importation duties on incoming slaves and used the funds to assist white poor people.326 Some laws ordered slaveowners to provide their slaves with adequate food and care, and were fined up to twenty pounds for breaches-with the fine going to benefit poor whites within the jurisdiction.327

Apprenticeship of Children

Like indenture, apprenticeship of children was voluntary for some and involuntary for others.328 Although there were considerable variations, children who were voluntarily apprenticed by their parents were usually contracted out until the age of twenty-one for boys, or sixteen for girls.329 The children received no wages, but did receive room, board, and training.330 Children were not free to leave their masters, and the masters were given authority to punish apprentices.331 Many children, however, were apprenticed out by town authorities in order to avoid the cost of providing assistance to their families.332

Colonial Poor Laws and Native Americans

When Europeans arrived in America they found Native Americans already there, people whom Columbus termed Indians.333 The conquering nations reacted to the presence of these Native Americans in slightly different ways, but with ultimately the same result-almost complete marginalization.334

Needless to say, there was little social welfare for native Americans during the colonial period-or later on, for that matter; most of those who survived were forced onto the nation’s worst lands where, out of sight, they were either ignored despite their poor plight, or placed on federal reservations administered by corrupt and uncaring officials.335

In addition to military force, the European nations used laws, contracts, and treaties to obtain their goals.336 This conquest, like all others, was justified and sustained by a sense of religious and cultural superiority.337

The English were primarily interested in development of agriculture. They began a process of occupying land for farming by ignoring native title.338 The French, less interested in agriculture than in the trade of fur, worked more with the Native Americans, occasionally seeking joint occupation and cooperation, hoping to use them as allies where possible.339 New Spain, on the other hand, never wavered in its push for conquest.340

There was little relief for Native Americans during the colonial period.341 Colonial laws that addressed concerns about the Indians were usually regulations of, rather than regulations for, them.342 Indians, like slaves and free people of color,’were ultimately outside the application of poor laws. If they were in need, Indians needed to find help among their own.

Recent Developments

In many ways, the welfare reforms of 1996 reflect a resurgence of several of the fundamental themes of colonial poor law. The new laws promote local responsibility for poor relief, promote three-generation family responsibility, and place increased restrictions on “strangers,” or aliens.

The latest reform of welfare is the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.343 The new law makes the colonial edict “work or starve” again a reality for the non-elderly, non-disabled poor of the United States. Work or community service is required in return for welfare or food stamp benefits.344 The latest welfare reform specifically eliminatesthe concept of any national entitlement.345 It moves the locus of poor law away from the federal government back to the states and local communities.346 Three-generation family responsibility is also revived.347

Current reform laws also have strong echoes of colonial settlement laws. First, there are reduced benefits allowed for poor people who originally resided in lower-benefit states.348 Second, there is an elimination of benefits for illegal aliens and non-resident aliens.349 Third, there is increased liability for poor relief imposed upon those who bring aliens into the country.350 In many ways, contemporary welfare laws in America are reverting back to the tenets of colonial poor laws.

Conclusion

Colonial poor laws were distinguished by principles both of compassion and control.351 The economic and social needs of the poor were balanced, mostly inequitably, with the needs of society as a whole. For the impoverished neighbor who was sick or unable to work, the colonies provided food and shelter. However, for those who would not work or those from outside the local community, there was little concern and no compassion. Given that poverty will exist for many in the foreseeable future, so will “poor laws.” It is society’s challenge and duty to responsibly balance the needs of the poor and nonpoor. We hope that history acts as a teacher and we can learn from our past mistakes. But if recent developments are any indication, we have yet to learn our lesson.

See endnotes at source.

Originally published by Legal Studies Research Paper Series, Loyola University New Orleans College of Law (12.19.1995) under an Open Access license.