By Dr. Garet Garrett

The Roman Republic passed into the Roman Empire, and yet never could a Roman citizen have said, “That was yesterday.” Nor is the historian, with all the advantages of perspective, able to place that momentous event at any exact point on the dial of time. The Republic had a long unhappy twilight. It is agreed that the Empire began with Augustus Caesar. Several before him had played emperor and were destroyed.

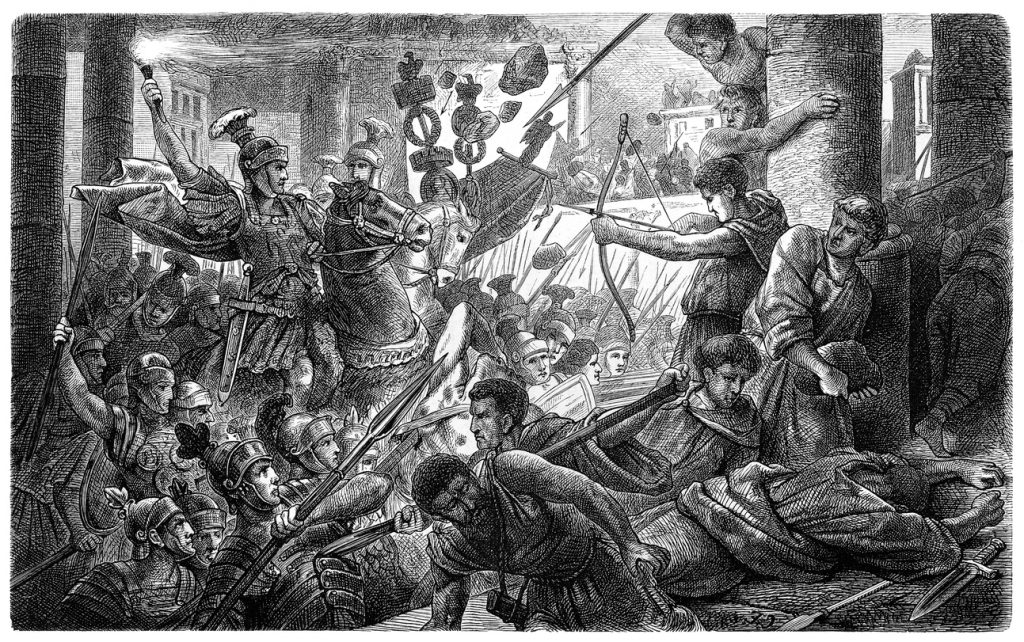

The first who might have been called emperor in fact was Julius Caesar, who pretended not to want the crown and once publicly declined it. Whether he feared more the displeasure of the Roman populace or the daggers of the republicans is unknown. In his dreams he may have been seeing a bloodstained toga. His murder soon afterward was a desperate act of the dying republican tradition, and perfectly futile. His heir was Octavian, and it was a very bloody business, yet neither did Octavian call himself emperor.

On the contrary, he was most careful to observe the old legal forms. He restored the Senate. Later he made believe to restore the Republic, and caused coins to be struck in commemoration of that event. Having acquired by universal consent, as he afterward wrote, “complete dominion over everything, both by land and sea,” he made a long and artful speech to the Senate, and ended it by saying: “And now I give back the Republic into your keeping. The laws, the troops, the treasury, the provinces, are all restored to you. May you guard them worthily.”

The response of the Senate was to crown him with oak leaves, plant laurel trees at his gate and name him Augustus. After that he reigned for more than forty years and when he died the bones of the Republic were buried with him. “The personality of a monarch,” says Stobart,

had been thrust almost surreptitiously into the frame of a republican constitution…. The establishment of the Empire was such a delicate and equivocal act that it has been open to various interpretations ever since. Probably in the clever mind of Augustus it was intended to be equivocal from the first.

What Augustus Caesar did was to demonstrate a proposition found in Aristotle’s “Politics,” one that he must have known by heart, namely this:

People do not easily change, but love their own ancient customs; and it is by small degrees only that one thing takes the place of another; so that the ancient laws will remain, while the power will be in the hands of those who have brought about a revolution in the state.

Revolution within the form.

There is no comfort in history for those who put their faith in forms; who think there is safeguard in words inscribed on parchment, preserved in a glass case, reproduced in facsimile and hauled to and fro on a Freedom Train.

This article was originally published as “The Decline of the American Republic” in The Freeman, February 25, 1952. Republished as a public domain resource.