You may know some of them for other parts of their histories.

These individuals fought for women’s suffrage. They lived across the United States, and came from around the world. Some were active in the battle for women’s right to vote in the early 1800s; others worked to educate and enroll voters and for voting rights into the late 1900s and beyond. Men and women, young and old, you may know some of them for other parts of their histories. Some you may never have heard of before.

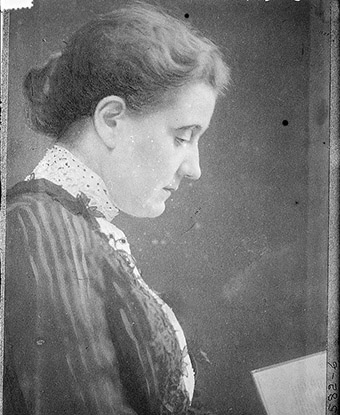

Jane Addams

Significance: Co-founder of Hull House, women’s rights advocate, sociologist, pacifist, Progressive

Place of Birth: Cedarville, IL

Date of Birth: September 6, 1860

Place of Death: Chicago, IL

Date of Death: May 21, 1935

Place of Burial: Cedarville, IL

Cemetery Name: Cedarville Cemetery

When Jane Addams penned Twenty Years at Hull House: With Autobiographical Notes, she presented her life story as inextricably tied to her work in running a settlement house. Addams was born into an affluent family in Illinois, but comfort and leisure did not suit her. After spending much of her early life searching for outlets for progressive work, Addams became a reformer. In 1889, this led her to found Hull House in Chicago, IL with a group of like-minded reformers.1 From within the walls of a spacious, abandoned mansion, Addams and her colleagues created a sanctuary for immigrants who wanted to both settle and thrive in the city. Addams saw this work as a major part of her life story; another examination shows that this was but one important chapter.

Prior to creating Hull House, Addams completed her education at Rockford Female Seminary. The president of her class, Addams was a bright and ambitious woman born to a well-connected family. Her father, Illinois senator John Addams, left a sizeable inheritance that enabled her to pursue her education even further. After Rockford, Addams enrolled at the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia, PA, but personal health issues derailed her career in medicine. Searching for her purpose, Addams set out to find a different kind of education; she soon embarked on an extensive, long tour of Europe.

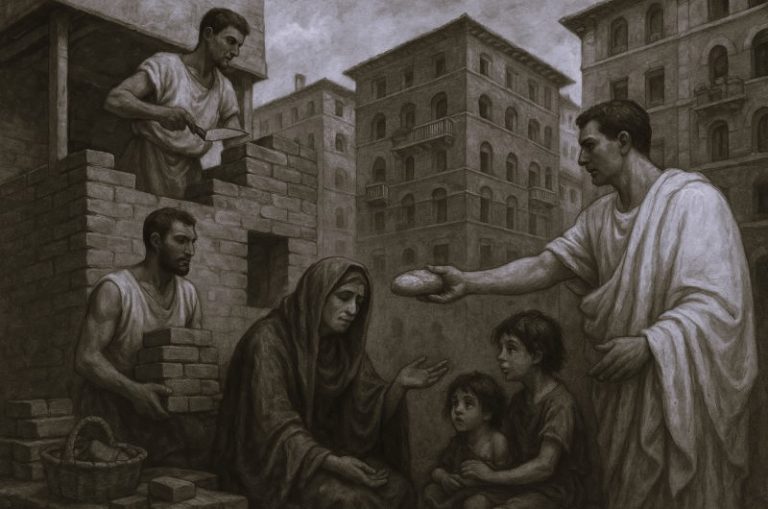

During her trip abroad, Addams became a critical observer of society. Deeply moved by the suffering of others, and especially the indigent, Addams sought solutions to the problems faced by residents of densely packed cities. Addams returned from this trip energized to create a settlement house similar to what she’d seen in Toynbee Hall, a social settlement in London. From her base at Hull House, which she co-founded with her partner, Ellen Gates Starr, Addams became a highly influential progressive in Chicago.2 In addition to providing direct social services for those who came through the settlement, Addams fought for better labor conditions, safe play spaces, cleaner city streets, a court system for juvenile offenders, and much more.

From the 1890s on, Addams became more involved with both progressive social issues and party politics. When Theodore Roosevelt ran for president in 1912, Addams offered her endorsement, seconding his nomination in Chicago during a convention of the Progressive Party. Addams had gained significant power and influence by this point through her advocacy work, yet she still could not vote. Addams continually campaigned for suffrage, both nationally and internationally, bemoaning that “It is always very difficult for me to make a speech on woman suffrage. I always feel that it belongs to the last century rather than this.”3 In 1913, the state of Illinois granted suffrage to women; the 19th Amendment was passed a few years later.

Addams was widely regarded as an important voice and conscience in this period known as the Progressive Era. Public opinion sharply changed when she fought against the entry of the United States in World War I. Throughout her life, an important tenant of Addams’s politics was pacifism. Addams was involved in the meeting of the International Congress of Women in 1915 at The Hague and she became a leader in the Women’s Peace Party and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Addams’s resistance to the war and accounting of worldwide suffering were seen by many, including agents within the Federal Bureau of Investigation, as unpatriotic.4

In 1931, just a few years before her death in May 1935, Addams was honored with a Nobel Peace Prize (shared with Nicholas Murray Butler). This came after a decade in which Addams was widely condemned for her pacifism. Addams may have found herself in Hull House, but the world was changed because she also used her voice so far outside of it, too.

Endnotes

- Hull House, 800 S. Halsted, Chicago, Illinois was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on June 23. 1965. The house and the dining room wing were documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Addams and Starr met in college. Addams later met, and set up house, with Mary Rozet Smith, who also worked with her at Hull House. They were together for over thirty years, reffering to each other as though they were married. Their relationship ended with Smith’s death in 1934.

- Jane Addams, “Speech on Woman Suffrage,” June 17, 1911.

- Jane Addams’ FBI Files

Susan B. Anthony

Significance: Suffragist, abolitionist, women’s rights advocate

Place of Birth: Adams, Massachusetts

Date of Birth: February 15, 1820

Place of Death: Rochester, New York

Date of Death: March 13, 1906

Place of Burial: Rochester, New York

Cemetery Name: Mount Hope Cemetery

Susan B. Anthony is perhaps the most widely known suffragist of her generation and has become an icon of the woman’s suffrage movement. Anthony traveled the country to give speeches, circulate petitions, and organize local women’s rights organizations.

Anthony was born in Adams, Massachusetts.1 After the Anthony family moved to Rochester, New York in 1845, they became active in the antislavery movement. Antislavery Quakers met at their farm almost every Sunday, where they were sometimes joined by Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Two of Anthony’s brothers, Daniel and Merritt, were later anti-slavery activists in the Kansas territory.

In 1848 Susan B. Anthony was working as a teacher in Canajoharie, New York and became involved with the teacher’s union when she discovered that male teachers had a monthly salary of $10.00, while the female teachers earned $2.50 a month. Her parents and sister Marry attended the 1848 Rochester Woman’s Rights Convention held August 2.

Anthony’s experience with the teacher’s union, temperance, and antislavery reforms, and her Quaker upbringing, laid fertile ground for a career in women’s rights reform to grow. The career would begin with an introduction to Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

On a street corner in Seneca Falls in 1851, Amelia Bloomer introduced Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and later Stanton recalled the moment:

“There she stood with her good earnest face and genial smile, dressed in gray silk, hat and all the same color, relieved with pale blue ribbons, the perfection of neatness and sobriety. I liked her thoroughly, and why I did not at once invite her home with me to dinner, I do not know.”

Meeting Elizabeth Cady Stanton was probably the beginning of her interest in women’s rights, but it is Lucy Stone’s speech at the 1852 Syracuse Convention that is credited for convincing Anthony to join the women’s rights movement.

In 1853 Anthony campaigned for women’s property rights in New York State, speaking at meetings, collecting signatures for petitions, and lobbying the state legislature. Anthony circulated petitions for married women’s property rights and woman suffrage. She addressed the National Women’s Rights Convention in 1854 and urged more petition campaigns. In 1854 she wrote to Matilda Joslyn Gage that “I know slavery is the all-absorbing question of the day, still we must push forward this great central question, which underlies all others.”

By 1856 Anthony had become an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, arranging meetings, making speeches, putting up posters, and distributing leaflets. She encountered hostile mobs, armed threats, and things thrown at her. She was hung in effigy, and in Syracuse, New York her image was dragged through the streets.

At the 1856 National Women’s Rights Convention, Anthony served on the business committee and spoke on the necessity of the dissemination of printed matter on women’s rights. She named The Lily and The Woman’s Advocate, and said they had some documents for sale on the platform.

Anthony and Stanton founded the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) and in 1868 became editors of its newspaper, The Revolution. The masthead of the newspaper proudly displayed their motto, “Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.” Also that year, the Fourteenth Amendment passed, recognizing that those born into slavery were entitled to the same citizenship status and protections as free people. The amendment did not, however, grant universal access to the vote. A rift appeared among those, like Stanton and Anthony and Frederick Douglass, who had been allies in the fight for universal suffrage. Anthony and Stanton were hurt that Douglass supported the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted the vote to Black men only. They felt he had abandoned woman suffrage. Douglass, in turn, was hurt by the insulting arguments of Anthony and Stanton against African Americans. They all thought that it would be impossible to get the vote for both women and African Americans at the same time, and disagreed with the others’ priorities. The rift turned ugly at a public meeting of the AERA held in New York City in 1869.

Following the meeting, Stanton, Anthony and others formed the National Woman Suffrage Association and focused solely on a federal woman’s suffrage amendment. In an effort to challenge suffrage, Anthony and her three sisters voted in the 1872 Presidential election. She was arrested at her Rochester, New York home and put on trial in the Ontario County Courthouse, Canandaigua, New York.2 The judge instructed the jury to find her guilty without any deliberations, and imposed a $100 fine. When Anthony refused to pay a $100 fine and court costs, the judge did not sentence her to prison time, which ended her chance of an appeal. An appeal would have allowed the suffrage movement to take the question of women’s voting rights to the Supreme Court, but it was not to be.

From 1881 to 1885, Anthony joined Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage in writing the History of Woman Suffrage. This extensive work focuses solely on white women suffragists, and does not include any suffragists of color.

In 1890, the National Woman Suffrage Association merged with the American Woman Suffrage Association, which argued for state-by-state enfranchisement of women (among other differences). Elizabeth Cady Stanton was the first president of the new group, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), but Anthony was effectively its leader. Anthony became NAWSA president in 1892. Carrie Chapman Catt replaced Anthony as president of the organization when she retired in 1900.

Susan B. Anthony also worked for other causes, including playing a key role in the creation of the International Council of Women and helping to organize the World’s Congress of Representative Women at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. She remained active until the end of her life. In 1893, Anthony started the Rochester branch of the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union. She also worked to raise money that the University of Rochester required before they would agree to admit women as students. In 1895, Anthony toured Yosemite National Park by mule.

Susan B. Anthony died on March 13, 1906 of heart failure and pneumonia at her Rochester home. She was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery, also in Rochester.3

As a final tribute to Susan B. Anthony, the Nineteenth Amendment was named the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. It was ratified in 1920. Susan B. Anthony is also the first non-fictional woman to be depicted on US currency: from 1979 to 1981 and again in 1999, her portrait was on the United States dollar coin.

Endnotes

- The Susan B. Anthony Birthplace at 67 East Road, Adams, Massachusetts, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 3, 1865. It is operated as an historic house museum.

- The Susan B. Anthony House, 17 Madison Street, Rochester, New York was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on June 23, 1965. The Ontario County Courthouse, Canandaigua, New York, is a contributing property of the Canandaigua Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 26, 1984 (boundary increase June 7, 2016).

- The Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 30, 2018.

Carrie Chapman Catt

Significance: Suffragist, peace activist, co-founder League of Women Voters

Place of Birth: Ripon, Wisconsin

Date of Birth: January 9, 1859

Place of Death: New Rochelle, NY

Date of Death: March 9, 1947

Place of Burial: Bronx, New York

Cemetery Name: Woodlawn Cemetery

Overview

Carrie Chapman Catt was born on January 9, 1859 in Ripon, Wisconsin, the daughter of Lucius and Maria Clinton Lane. In 1866 the Lane family moved to a modest Victorian house on a farm near Charles City, Iowa.1 Carrie Lane graduated from the Charles City High School in 1877 and immediately enrolled in the Iowa State College in Ames.2 Her father, who was reluctant to have his daughter attend college, contributed only part of her expenses. To cover the rest of her expenses, Catt worked as a dishwasher, in the school library, and as a rural school teacher. Catt’s activist personality was evident in college. While there, she started an all girls’ debate club and advocated for women’s participation in military drills. She graduated on November 10, 1880 with a Bachelor of Science degree — the only woman in her graduating class.

Early Career and Activism

After graduation, Catt worked as a law clerk and a teacher. In 1885, she was hired as superintendent of schools in Mason City, Iowa, the first woman to hold that position in the district. That year, she married Leo Chapman, a newspaper editor, and moved with him to San Francisco. He died in August 1886 of typhoid fever. Carrie moved back to Charles City, Iowa in 1887 and became involved in the Iowa Woman Suffrage Association.

In 1890, she married fellow Iowa State alum, George Catt. A wealthy engineer, he and Carrie agreed that she would spend at least four months each year on women’s suffrage efforts. From 1890 to 1892, she held office in the Iowa Woman Suffrage Association, and became involved in the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), under its president, Susan B. Anthony. She spoke at the NAWSA convention in Washington, DC in 1890, and in 1892, addressed Congress on the proposed woman’s suffrage amendment, at the invitation of Susan B. Anthony.

In 1900, Catt succeeded Anthony as president of NAWSA, serving until 1904 when she resigned to care for her ailing husband. Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw took over as NAWSA president. After the death of her husband in 1905 and Susan B. Anthony in 1906, Catt again became involved in women’s suffrage and was re-elected president of NAWSA in 1915. She created the “Winning Plan,” a campaign to encourage each state to give women the right to vote and to urge Congress to pass an amendment to this effect. Membership in NAWSA grew to over two million by 1917. With Jane Addams, she founded the Woman’s Peace Party in 1915, but when the United States entered World War I in 1917, she threw herself into organizations supporting the war effort.

Race and Immigration

Suffragists did not necessarily support universal civil rights. Early in her career, Catt espoused nativist beliefs. In 1894, for example, she warned that the United States was “menaced with great danger…in the votes posessed by the males in the slums of the cities and the ignorant foreign vote.” Her solution was to “cut off the vote of the slums and give [it] to woman.”3 Like other white suffragists, Catt was frustrated by what she saw as hypocrisy: “ignorant” men allowed to vote while educated women could not.

Over time, Catt and other white suffrage leaders became experts in making their case for suffrage to the various groups of men they needed to win over. In 1917, Catt edited a manual for suffrage workers with details about arguments against suffrage and advice on how to refute them. In it, she noted that Southern white supremacists often opposed the federal suffrage amendment by arguing that it would enfranchise Black women and thus threaten white supremacy. Catt pointed out that in most Southern states, there were more white women than Black women; and that in those states with a larger Black population, Jim Crow voting restrictions would apply to women as well as men. She wrote that “white supremacy will be strengthened, not weakened, by woman suffrage.”4 While Catt herself was not a champion of white supremacy, she and many other white suffragists still used this argument to persuade white Southerners whose goal was to uphold it.

At other times, Catt made inclusive statements about voting rights. For example, that same year she contributed an article to The Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). “Just as the world war is no white man’s war, but every man’s war, so is the struggle for woman suffrage no white woman’s struggle, but every woman’s struggle,” she wrote. “Everybody counts in applying democracy. And there will never be a true democracy until every law-abiding adult in it, without regard to race, sex, color or creed has his or her own inalienable and unpurchaseable voice in government.”5

Later Career and Life

In 1919, just after the 19th Amendment began its long ratification process, Catt bought Juniper Ledge in New Castle, New York. The rural home was, in Catt’s description, a place to rest her “tired nerves.” While living in this home with her partner of 20 years, Mary “Mollie” Garrett Hay (an active New York State suffragist), Catt began working on an idea for an organization called the League of Women Voters. She was also active in promoting the 19th Amendment; in the fall of 1919, she toured 13 states advocating for its ratification. In May of 1920, the amendment was passed by Congress and a cablegram from President Wilson congratulating her read, “Glory Hallelujah!”

After the passage of the 19th Amendment, Catt continued her work. From 1920-1922, Catt worked for suffrage in Europe and South America. In 1923 she started the organization called the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. She met Mussolini in Rome and made a strong, challenging suffrage speech directly to him. In the mid-1920s, Catt returned to her pre-war interest in peace, and in 1925 she founded the Committee for the Cause and Cure of War.

In 1928, Catt sold Juniper Ledge and she and her partner, Mary Garrett Hay (a New York State suffragist) moved to a colonial revival house in New Rochelle, New York. Hay died shortly after the move. From her New Rochelle home, Catt continued her activism with the help of her live-in assistant and companion, Alda Wilson. In 1933, Catt organized the Protest Committee of Non-Jewish Women Against the Persecution of Jews in Germany, which sent a 9,000-signature petition to Hitler condemning violence and restrictive laws against German Jews. Catt and the organization also pressured the federal government to ease immigration laws to make it easier for Jews to find refuge in the United States.6 For her work, she was the first woman to receive the American Hebrew Medal.

Catt died of a heart attack in her home on March 8, 1947. She was buried, at her request, in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City, beside Mary Hay, who had been her partner for decades.7

Endnotes

- The Carrie Chapman Catt Childhood Home (officially known as the Lucius and Maria Clinton Lane House and also as the Carrie Lane Chapman Family Home) was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 25, 1998.

- The Farm House (Knapp-Wilson House) is the oldest building on the campus of Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa. Built in the first half of the 1860s, it was present when Carrie Chapman Catt attended the university. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on July 19, 1964.

- Carrie Chapman Catt, “Danger to Our Government,” Dec. 15, 1884. https://awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu/2017/03/21/danger-to-our-government-dec-15-1894/

- Carrie Chapman Catt, “Objections to the Federal Amendment,” in Woman Suffrage by Federal Constitutional Amendment, ed. Carrie Chapman Catt (New York: National Woman Suffrage Publishing Co., 1917), 76. https://lccn.loc.gov/17004988

- Carrie Chapman Catt, “Votes for All,” The Crisis 15, no. 1 (1917): 20.

- Despite the efforts of Catt and others, public anti-immigration sentiment was strong. All of the bills that were proposed in Congress to aide refugees at the time were rejected. Holocaust Encyclopedia.

- Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx was designated a National Historic Landmark on June 23, 2011.

Septima Poinsette Clark

Significance: Civil rights activist, founder of Citizenship Schools

Place of Birth: Charleston, SC

Date of Birth: May, 1898

Place of Death: Johns Island, SC

Date of Death: December, 1987

Place of Burial: Charleston, SC

Cemetery Name: Old Bethel United Methodist Church Cemetery

Septima Poinsette Clark was a civil rights activist born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1898. She attended the Avery Normal Institute and graduated in 1916. When she was 18, Clark started her career as a school teacher in a one room schoolhouse. She wanted to do more to advance the rights of African Americans and she joined the Charleston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Many southern states enforced segregation until the mid-1900s, meaning that white schools did not allow African American students to attend. Due to the color of her skin, Clark was not allowed to teach in the Charleston public school system, and instead she had to accept teaching positions in rural school districts. Clark and others thought this was unfair and they protested to win African Americans the right to teach at Charleston public schools. The campaign was successful and Clark was convinced that social activism had the power to better the lives of African Americans.

In the 1950s, Clark and the NAACP advocated for the integration of public schools. Her involvement in the NAACP did not go unnoticed by the Charleston City School Board. Clark was asked to keep her membership in the NAACP a secret, but she refused. As a result, the school board fired her. No longer employed, she devoted all of her time to activism.

Clark was particularly upset by the voting system in the South. Black men and women had the right to vote, but were often kept from the voting polls by literacy tests. Many adult African Americans could not read because their parents and grandparents were formerly enslaved. Slavery was legal in the United States until 1865, and it was illegal to teach an enslaved person to read and write. As a result, literacy tests prevented many black citizens from voting, even in the 1950s and 1960s.

Clark designed educational programs to teach African American community members how to read and write. She thought this was important in order to vote and gain other rights. Her idea for “citizen education” became the cornerstone of the Civil Right Movement. She worked with Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to win rights for African Americans.

Septima Clark continued to serve as an advocate and a leader until her death in 1987.

References

- Blackmore, Erin. “How Septima Poinsette Clark Spoke Up for Civil Rights.” (Feb, 2016). JSTOR Daily, http://daily.jstor.org/how-septima-clark-spoke-up-for-civil-rights/.

- Charron, Katherine Mellen. Freedom’s Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

- Rouse, Jacqueline A. “‘We Seek to Know …in Order to Speak the Truth:’ Nurturing the Seeds of Discontent – Septima P. Clark and Participatory Leadership.” In Sisters in the Struggle: African American Women in the Civil Rights-Black Power Movement. Edited by Bettye Collier-Thomas, V.P. Franklin. New York: New York University Press, 2001.

Frederick Douglass

Significance: Former slave who became America’s foremost abolitionist. Suffragist, publisher, author.

Place of Birth: Talbot County, MD

Date of Birth: February, 1818

Place of Death: Washington, DC

Date of Death: February 20, 1895

Place of Burial: Rochester, NY

Cemetery Name: Mount Hope Cemetery

Overview

In his journey from captive slave to internationally renowned activist, Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) has been a source of inspiration and hope for millions. His brilliant words and brave actions continue to shape the ways that we think about race, democracy, and the meaning of freedom.

Slavery and Escape

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in February 1818. He had a difficult family life. He barely knew his mother, who lived on a different plantation and died when he was a young child. He never discovered the identity of his father. At the age of six, he was separated from his grandmother and sent to Wye House Plantation in Maryland.1 When he turned eight years old, his slaveowner hired him out to work as a body servant in Baltimore.

At an early age, Frederick realized there was a connection between literacy and freedom. Not allowed to attend school, he taught himself to read and write in the streets of Baltimore. At twelve, he bought a book called The Columbian Orator. It was a collection of revolutionary speeches, debates, and writings on natural rights.

When Frederick was fifteen, his slaveowner sent him back to the Eastern Shore to labor as a fieldhand. Frederick rebelled intensely. He educated other slaves, physically fought back against a “slave-breaker,” and plotted an unsuccessful escape.

Frustrated, his slaveowner returned him to Baltimore. This time, Frederick met a young free Black woman named Anna Murray, who agreed to help him escape. On September 3, 1838, he disguised himself as a sailor and boarded a northbound train, using money from Anna to pay for his ticket. In less than 24 hours, after traveling by train, ferry boat, and on foot, Frederick arrived in New York City and declared himself free. He had successfully escaped from slavery.

The Abolitionist Movement

After escaping from slavery, Frederick married Anna. They decided that New York City was not a safe place for Frederick to remain as a fugitive, so they settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts. There, they adopted the last name “Douglass” and they started their family, which would eventually grow to include five children: Rosetta, Lewis, Frederick Jr., Charles, and Annie.

After finding employment as a laborer, Douglass began to attend abolitionist meetings and speak about his experiences in slavery. He soon gained a reputation as an orator, landing a job as an agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. The job took him on speaking tours across the North and Midwest.

Douglass’s fame as an orator increased as he traveled. Still, some of his audiences suspected he was not truly a fugitive slave. In 1845, he published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, to lay those doubts to rest. The narrative gave a clear record of names and places from his enslavement.

To avoid being captured and re-enslaved, Douglass traveled overseas. For almost two years, he gave speeches and sold copies of his narrative in England, Ireland, and Scotland. When abolitionists offered to purchase his freedom, Douglass accepted and returned home to the United States legally free. He relocated Anna and their children to Rochester, New York.

In Rochester, Douglass took his work in new directions. He embraced the women’s rights movement, helped people on the Underground Railroad, and supported anti-slavery political parties. Once an ally of William Lloyd Garrison and his followers, Douglass started to work more closely with Gerrit Smith and John Brown. He bought a printing press and ran his own newspaper, The North Star. In 1855, he published his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, which expanded on his first autobiography and challenged racial segregation in the North.

Woman Suffrage

Douglass was active with the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society, and it was through this organization that he met Elizabeth M’Clintock. In July of 1848, M’Clintock invited Douglass to attend the First Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York. Douglass readily accepted, and his participation at the convention revealed his commitment to woman suffrage. He was the only African American to attend. In an issue of the North Star published shortly after the convention, Douglass wrote,

In respect to political rights, we hold woman to be justly entitled to all we claim for man. We go farther, and express our conviction that all political rights which it is expedient for man to exercise, it is equally so for women. All that distinguishes man as an intelligent and accountable being, is equally true of woman; and if that government is only just which governs by the free consent of the governed, there can be no reason in the world for denying to woman the exercise of the elective franchise, or a hand in making and administering the laws of the land. Our doctrine is, that “Right is of no sex.”

Douglass continued to support the cause of women after the 1848 convention. In 1866 Douglass, along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, founded the American Equal Rights Association, an organization that demanded universal suffrage. Though the group disbanded just three years later due to growing tension between women’s rights activists and Africa-American rights activists, Douglass remained influential in both movements, championing the cause of equal rights until his death in 1895.

Civil War and Reconstruction

In 1861, the nation erupted into civil war over the issue of slavery. Frederick Douglass worked tirelessly to make sure that emancipation would be one of the war’s outcomes. He recruited African-American men to fight in the U.S. Army, including two of his own sons, who served in the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. When black troops protested they were not receiving pay and treatment equal to that of white troops, Douglass met with President Abraham Lincoln to advocate on their behalf.

As the Civil War progressed and emancipation seemed imminent, Douglass intensified the fight for equal citizenship. He argued that freedom would be empty if former slaves were not guaranteed the rights and protections of American citizens. A series of postwar amendments sought to make some of these tremendous changes. The 13th Amendment (ratified in 1865) abolished slavery, the 14th Amendment (ratified in 1868) granted national birthright citizenship, and the 15th Amendment (ratified in 1870) stated nobody could be denied voting rights on the basis of race, skin color, or previous servitude.

In 1872, the Douglasses moved to Washington, D.C. There were multiple reasons for their move: Douglass had been traveling frequently to the area ever since the Civil War, all three of their sons already lived in the federal district, and the old family home in Rochester had burned. A widely known public figure by the time of Reconstruction, Douglass started to hold prestigious offices, including assistant secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission, legislative council member of the D.C. Territorial Government, board member of Howard University, and president of the Freedman’s Bank.

Post-Reconstruction and Death

After the fall of Reconstruction, Frederick Douglass managed to retain high-ranking federal appointments. He served under five presidents as U.S. Marshal for D.C. (1877-1881), Recorder of Deeds for D.C. (1881-1886), and Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti (1889-1891). Significantly, he held these positions at a time when violence and fraud severely restricted African-American political activism.

On top of his federal work, Douglass kept a vigorous speaking tour schedule. His speeches continued to agitate for racial equality and women’s rights. In 1881, Douglass published his third autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which took a long view of his life’s work, the nation’s progress, and the work left to do. Although the nation had made great strides during Reconstruction, there was still injustice and a basic lack of freedom for many Americans.

Tragedy struck Douglass’s life in 1882 when Anna died from a stroke. He remarried in 1884 to Helen Pitts, an activist and the daughter of former abolitionists. The marriage stirred controversy, as Helen was white and twenty years younger than him. Part of their married life was spent abroad. They traveled to Europe and Africa in 1886-1887, and they took up temporary residence in Haiti during Douglass’s service there in 1889-1891.

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting for the National Council of Women. He returned home to Cedar Hill in the late afternoon and was preparing to give a speech at a local church when he suffered a heart attack and passed away.2 Douglass was 77. He had remained a central figure in the fight for equality and justice for his entire life.

Frederick Douglass’ funeral was held at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in DC. He was buried next to his wife Anna in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York. His second wife, Helen, joined them in the Douglass family plot after her death in 1903.3

Endnotes

- Wye House Plantation was designated a National Historic Landmark on April 15, 1970.

- Frederick and Anna moved into their DC home in 1877, naming it Cedar Hill. The home and the surrounding estate make up the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, a unit of the National Park Service.

- The Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church, 1518 M Street NW, Washington, DC was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 26, 1973. Mount Hope Cemetery, Rochester, New York was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 30, 2018.

Wilhelmina Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett

Significance: Suffragist

Place of Birth: Lihue, Kingdom of Hawai’i

Date of Birth: March 28, 1861

Place of Death: Honolulu, Territory of Hawai’i

Date of Death: December 10, 1929

Place of Burial: Honolulu, Hawai’i

Cemetery Name: Oahu Cemetery

Born in 1861 at Lihue, Kauai in the Kingdom of Hawaii, Wilhelmina Kekelaokalaninui Widemann was the daughter of Mary Kaumana Pilahiulani, a Native Hawaiian, and German immigrant Hermann A. Widemann. Part of the Royal Hawaiian family, her father was a cabinet minister for Queen Lili’uokalani. Due to these connections, King Kalākaua and Queen Kapi’olan were present at her wedding to Jack Dowsett in 1888.

Five short years later, pro-American interests, with the assistance of US Marines, overthrew Queen Lili’uokalani and established the Republic of Hawai’i. The former island nation was annexed to the United States in 1898. With the introduction of this new territory to the Union, the mainland suffragists turned their eyes towards the Pacific to see if any progress could be made.

Written by Susan B. Anthony and other officers of the NAWSA, the “Hawaiian Appeal” of 1899 asked the US Congress to give Hawaiian women the right to vote “upon whatever conditions and qualifications the right of suffrage is granted to Hawaiian men.” While Anthony and others wanted all women to have voting rights, they were especially concerned about non-Christian Native Hawaiian men gaining that power before the white and Native Hawaiian women of the territory. The Hawaiian Appeal received criticism from almost all corners. Local women, like Dowsett, felt that petitioning the territorial government for greater civil rights was the way to go.

In 1912, Dowsett founded the National Women’s Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai’i (WESAH), the first Hawaiian suffrage organization. Modeling its constitution on that of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), they invited mainland suffragists to speak to the group. One of these women included Carrie Chapman Catt in 1918, who spoke in positive terms about the group after the meeting.

Thanks to the efforts of women like Dowsett and WESAH, President Wilson signed a bill allowing the residents of the territory to decide for themselves. Gathering both Native Hawaiian and white suffragists at the capitol building on the morning of the Senate vote on March 4, 1919, Dowsett declared:

“Sister Hawaiians, our foreign sisters are with us. Senator Wise asked us yesterday if the so-called ‘society women’ were leading us, and we told him that this was not so. We are working all together, and we want the legislature to know this. And we must also remember our Oriental sisters, who are not here today but who will also unite this great cause.”’

While many in the territory, like those on the mainland, were against granting the right of suffrage to Asian women, Dowsett included them in her vision of Hawai’i’s future. The bill passed the Hawaiian Senate that day, but a fresh battle was waiting in the House. Instead of granting women’s suffrage immediately, the House decided to put it to a vote of the Hawaiian electorate in 1920. Furious with that response, Dowsett and 500 other women of “various nationalities, of all ages” poured onto the House floor with banners demanding “Votes for Women.” Forced to reckon with the demonstrators, the House held hearings the next day for proponents and opponents to make their case. Standing alongside Dowsett were a wide variety of Hawai’ian women including Princess Kalaniana’ole and Lahilahi Webb, former lady-in-waiting to Queen Lili’uokalani’s court.

A month later, the House had not budged and the suffragists of Hawai’i were losing their patience. Regrouping, Dowsett and her group began to lobby directly to the U.S. Congress through the territorial representative, Prince Kūhiō. They also began to create grassroots groups throughout the territory to prepare women for the vote when that opportunity arrived. Hawaiian women became enfranchised along with their mainland sisters when the 19th Amendment became part of the U.S. Constitution in August 1920. As residents of a U.S. territory, however, their elected representation was limited.

It would take another 39 years for Hawai’i to become the 50th state in the Union, and for the residents of Hawai’i, both male and female, to gain full US voting rights. Dowsett did not live long enough to see that day; she died December 10, 1929. She is buried next to her husband in Oahu Cemetery, Honolulu.

Bibliography

- Barker, Joanne. Indigenous Feminisms. The Oxford Handbook of Indigenous People’s Politics, edited by Jose Antonio Lucero, Dale Turner, and Donna Lee VanCott. Oxford University Press, published online 2015.

- Choy, Catherine Ceniza, and Judy Tzu-Chun Wu. Gendering the Trans- Pacific World. Brill, 2017.

- “Hawaii.” US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/APA/Historical-Essays/Exclusion-and-Empire/Hawaii/

- “Hawaiian Women Join with Haoles to Work for Vote.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 5 Mar. 1919.

- Sneider, Allison L. Suffragists in an Imperial Age US Expansion and the Woman Question, 1870-1929. Oxford University Press, 2008.

First Territorial Legislature of Alaska

Significance: First act of the just-formed Territorial Legislature was to grant women the vote in 1913.

On March 30, 1867 the United States purchased Alaska from what was then the Russian Empire. Forty-five years later, in 1912, the US Congress voted to create the Territory of Alaska and establish the Alaska Territorial Legislature. The first session of the legislature met from March 3 to May 1, 1913 in the Juneau Elks Lodge.1 Their first act of the all-male Territorial Legislature was to grant Alaska women the right to vote.

House Bill No. 2, An Act to Extend the Elective Franchise to Women in the Territory of Alaska, reads:

Be it enacted by the legislature of the Territory of Alaska: That in all elections which are now, or may be hereafter authorized by law in the Territory of Alaska, or any sub-division or municipality thereof, the elective franchise is hereby extended to such women as have the qualifications of citizenship required of male electors.

The bill passed the House on March 14, 1913; passed the Senate on March 18, 1913; and was signed into law by the Governor of Alaska Territory, Walter Eli Clark, on March 21, 1913.2

Excluded from voting were Alaska Natives, who were denied the vote and participation in elections by the Act that established the Alaska Territory. Activists from the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Sisterhood advocated for Native suffrage rights. In 1915, the Alaska Territorial Legislature recognized the right of Indigenous people to vote on the condition they gave up tribal customs and traditions.

In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act was signed into law, granting US citizenship to all Native Americans — including those in Alaska, and regardless of whether they gave up their culture. But states could limit who had access to the vote, and many states — including Alaska — excluded certain groups from the ballot. In Alaska, as in many of the Southern US states, the Territorial Legislature passed a literacy requirement for all new voters. While it seems as though the law was only selectively enforced, it remained in effect, and became part of the Alaska State Constitution.

Alaska did not become a US state until January 3, 1959 and so was unable to vote to ratify the 19th Amendment before it became law in 1920.

Endnotes

- First Territorial Legislature members were: Senate: Elwood Bruner, Conrad Freeding, Thomas McGann, B.F. Millard, L.V. Ray (Senate President), Henry Roden, Dan Sutherland, J.M. Tanner, and Herman Tripp. House: Frank Aldrich, Frank Boyle, William Burns, Earnest Collins (Speaker of the House), Daniel Driscoll, Thomas Gaffney, Robert Gray, Charles Ingersoll, H.B. Ingram, Charles D. Jones, Milo Kelly, James C. Kennedy, J.J. Mullaly, Arthur Shoup, William Stubbins, and N.J. Svindseth.

- Clark lived in the Alaska Governor’s Mansion in Juneau; he was its first occupant when it was built in 1912. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on November 7, 1976. It is within the Juneau Downtown Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 17, 1994.

Dolores Huerta

Significance: Labor organizer; co-founder of the National Farm Workers Association; works to register voters

Place of Birth: Dawson, New Mexico

Date of Birth: April 10, 1930

Dolores Huerta was born Dolores Clara Fernández on April 10, 1930, in the mining town of Dawson, New Mexico. She was the daughter of Juan Fernández and Alicia Chávez. Her father was a farm worker, miner, and union activist elected to the New Mexico legislature in 1938. When she was three, her parents divorced. Huerta moved with her two brothers and mother to Stockton, California, where she spent most of her childhood and early adult life.

Huerta’s mother was known in the local community for her kindness and compassion. She was actively engaged in her community of working families of Mexican, Filipino, African American, Japanese, and Chinese descent. Huerta later credits her mother with providing her with the inspiration for her nonviolent stance and her work organizing farmworkers.

Huerta earned a teaching credential from University of the Pacific’s Delta College in Stockton. After graduating, she worked teaching the children of farmworkers. It was this experience that catalyzed her into her labor activism. She recalls, “I couldn’t tolerate seeing kids come to class hungry and needing shoes. I thought I could do more by organizing farm workers than by trying to teach their hungry children.” She left teaching to work in the leadership of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which worked for the economic improvement of Latinos. In 1955, during her work with the CSO, Huerta was introduced to César Chávez, its executive director. In 1960, Huerta founded the Agricultural Workers Association, which organized voter registration drives.

Huerta and Chávez soon realized they shared interest in organizing farm workers. In 1962, they left the CSO to launch the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). In 1965, the NFWA was approached by grape workers in Delano, California to support their strike. They were striking for a wage increase. The Delano workers were mostly Filipino laborers affiliated with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). The NFWA merged with the AWOC, ultimately forming the United Farm Workers of America in 1966.

Huerta took an intersectional analysis to organizing the farm workers, meaning that she considered how the specific needs of workers varied depending on their diverse identities. She observed that women farm workers were at unique risk of sexual violence, and that the children of farm workers had specific concerns for their rights as younger laborers in the fields working alongside their parents. Her concern for the needs of the families of workers influenced her stance on the necessity of nonviolent action.

Huerta is still active in community organizing. In 2003, she established the Dolores Huerta Foundation for grassroots community organizing. The Foundation works to organize communities and develop future leaders. Huerta often advocates and encourages Latina women to become involved in public office. She sees the work of her foundation as continuing the legacies of the nonviolent movements for civil rights that she participated in. The Foundation continues to engage California residents in voter registration drives and nonpartisan candidate forums, continuing Huerta’s work that she began with the Agricultural Workers Association in 1960.

Dolores Huerta is the recipient of the Eleanor Roosevelt Award for Human Rights (granted by the President of the United States), the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and other awards. In 1993, he was the first Latina inducted into the US National Women’s Hall of Fame. She has also been recognized by the communities she fought for: numerous murals and corridos (a traditional Mexican type of song) have been created in her honor.

Helen Keller

Significance: Civil rights activist; women’s rights activist; author; speaker

Place of Birth: Tuscumbia, Alabama

Date of Birth: June 27, 1880

Place of Death: Easton, Connecticut

Date of Death: June 1, 1968

Place of Burial: Washington, DC

Cemetery Name: National Cathedral

Helen Keller was born to a prominent family in Tuscumbia, Alabama in 1880.1 When she was nineteen months old, Keller lost her ability to see and hear. As part of their efforts to communicate with Helen, her parents Arthur and Catherine Keller turned to the Perkins School for the Blind, based in Watertown, Massachusetts. A Perkins graduate named Anne Sullivan was sent to the Keller home to train Helen in her seventh year. Sullivan famously taught Keller to read braille and in time, Keller was able to communicate through both sign language and aural speech.

Following the completion of her studies at the Cambridge School for Young Ladies, Keller enrolled at Radcliffe College. While completing her collegiate studies, Keller wrote her autobiography, The Story of My Life, first published in 1904.2 All of her work as student and author was done in conjunction with Sullivan, who became a lifelong friend.

A self-described “militant suffragette,” Keller used the considerable notoriety she gained in her adolescence to advocate for others for the rest of her life. In 1913, Keller participated in the large parade known as the “Woman Suffrage Procession” in Washington, DC. Her interest in women’s rights was rooted in her connections to contemporary labor movements. Keller was particularly interested in working people’s issues, including industrial safety standards, which led to membership in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Keller’s radical politics also included supporting the movement to increase access to birth control for women. When a biographical film called Deliverance, which featured Keller, premiered in New York City, she joined with striking actors instead of attending.

Keller regularly gave lectures in support of the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) to earn a living. Though she was interested in persons with disabilities, it is important to note the breadth of Keller’s interests. Later in life, Keller was particularly passionate and dedicated to global causes, including anti-imperialism. An anti-war philosopher and agitator, Keller protested World War I and later, World War II.

Over the course of her lifetime, Keller would become one of the world’s best-known people with a disability. A complex woman with a range of political affiliations, Keller is often remembered for her early triumphs. This early focus misses Keller’s evolution and the contributions she made to a variety of causes. Keller was born into affluence and comfort; she died nearly ninety years later a devoted revolutionary who had worked tirelessly to make the oppression of others better understood. Her ashes, as well of those of her companion, Anne Sullivan, are interred at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC.3

Endnotes

- Helen Keller was born at home. The property, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is known as Ivy Green.

- The Story of My Life has been adapted for film and stage as The Miracle Worker.

- The National Cathedral was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 3, 1974. Anne Sullivan was the first woman whose remains were interred here.

References

- Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (New York: Double Day, Page & Co., 1904).

- Helen Keller, Out of the Dark: Essays, Lectures, and Addresses on Physical and Social Vision (New York: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1920).

- Kim E. Nielson, The Radical Lives of Helen Keller (New York: New York University Press, 2004).

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Significance: Suffragist who mobilized the Chinese community in America to support women’s right to vote

Place of Birth: China

Date of Birth: 1896

Place of Death: New York City?

Date of Death: 1966

Mabel Lee was a suffragist who mobilized the Chinese community in America to support women’s right to vote. Because Chinese immigrants were not considered citizens, the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which removed voting restrictions on the basis of sex, did not give Mabel the right to vote.

Mabel Lee was born in Guangzhou (Canton), not far from Hong Kong in China in 1896. When she was 4, her father moved to the US to serve as a missionary. Lee remained in Hong Kong and lived with her mother and grandmother. She learned English at a missionary school and won a Boxer Indemnity Scholarship. This academic scholarship granted her a US visa and the Lee family settled in New York City’s Chinatown in 1905. Mabel attended Erasmus Hall Academy in Brooklyn.

By the time she was 16, Mabel Lee was a known figure in New York’s suffrage movement. New York City suffragists held a parade in 1912 to advocate for women’s voting rights. Ten thousand people attended the parade. Lee, on horseback, helped lead the parade from its starting point in Greenwich Village. The New York Tribune wrote an article about her before the parade. The article highlighted her academic accomplishments and her desire to improve the lives of women and girls. She was also mentioned in the New York Times’ parade coverage.

Lee started her studies at Barnard College in New York City in 1912. Barnard College, an all-women’s school, was founded because Columbia University refused to admit women. While there, Mabel joined the Chinese Students’ Association and wrote feminist essays for The Chinese Students’ Monthly. Lee was involved in the suffrage movement throughout college. Her May 1914 essay, “The Meaning of Woman Suffrage,” argued that suffrage for women was necessary to a successful democracy. The extension of democracy (through voting) and “equality of opportunities to women” was, she stated, the hallmarks of true feminism. In 1915, the Women’s Political Union started a Suffrage Shop and invited Lee to give a speech. Covered by the New York Times, her speech “The Submerged Half” urged the Chinese community to promote girls’ education and women’s civic participation.

Women won the right to vote in New York State in 1917. In 1920, the 19th Amendment gave women throughout the country the right to vote. But not all women in the US benefitted. Chinese women, like Mabel Lee, could not vote until 1943. This was because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, a Federal law in place from 1882 to 1943. The Chinese Exclusion Act limited Chinese immigration and prevented Chinese immigrants from becoming citizens. Without US citizenship, Mabel Lee could not vote. Yet, she and other Chinese suffragists advocated for women’s voting rights, even though they did not benefit from the legislation.

After graduating from Barnard College, Lee got a PhD in economics at Columbia University. She was the first Chinese woman to do so. In 1921, Lee published her research as a book called The Economic History of China.

Ever since high school, Mabel had wanted to move back to China and start a girl’s school. But after her father died in 1924, she took over his role as director of the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City. She later founded the Chinese Christian Center which served as a community center. It offered vocational and English classes, a health clinic, and a kindergarten. Lee never married and devoted her life to the Chinese community.

Mabel Lee died in 1966. We don’t know if Mabel Lee ever became a US citizen or if she ever voted in the US.

Bibliography

- Brooks, Charlotte (2014) “Suffragist Landmark.” Asian American History in NYC: Finding the Asian American Past in the Five Boroughs, August 25, 2014.

- Harvard University Library (2018) “Chinese Exclusion Act (1882).” Aspiration, Acculturation, and Impact: Immigration to the United States, 1789-1930, Harvard University Library Open Collection Program.

- Lee, Mabel (1915) “China’s Submerged Half.” (.pdf)

- New York Times (1912) “Suffrage Army Out on Parade; Perhaps 10,000 Women and Men Sympathizers March for the Cause.” New York Times, May 5, 1912.

- New York Tribune (1912) “Chinese Girl Wants Vote.” New York Tribune, April 13, 1912, p. 3. Available through the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America project.

- Tseng, Timothy (1996) “Dr. Mabel Lee: The Interstitial Career of a Protestant Chinese American Woman, 1924-1950.” Paper presented at the Organization of American Historians Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois. Paper available online (.pdf).

- (2013) “Asian American Legacy: Dr. Mabel Lee.” Author website, December 12, 2013.

- (2017) “Chinatown’s Suffragist, Pastor, and Community Organizer.” Christianity Today: Christian History, June 2017.

Adelina (“Nina”) Otero-Warren

Significance: Suffragist, author, business woman, homesteader

Place of Birth: “La Constancia,” her family’s hacienda near Los Lunas, New Mexico

Date of Birth: October 23, 1881

Place of Death: Santa Fe, New Mexico

Date of Death: January 3, 1965

Place of Burial: Santa Fe, New Mexico

Cemetery Name: Rosario Cemetery

Deftly negotiating between Hispano, Anglo, and American Indian worlds throughout her life, Adelina Isabel Emilia Luna Otero was born on October 23, 1881 on her family’s hacienda near Los Lunas, New Mexico.

The Otero family were wealthy and politically powerful in the Rio Abajo (Lower River) region of what is now New Mexico. The family of her mother, Eloisa Luna Otero, were descended from some of the earliest colonists in New Mexico; the family of her father, Manuel B. Otero, traced his lineage to the Spanish occupation of the area in the 1700s. As a child, she was known as Adelina Otero; as an adult, friends and family called her Nina.

Once railroads arrived in the region in 1881, white immigrants (known as Anglos) began traveling west in large numbers, actively displacing the Native American, Spanish, and Mexican populations who were already there (though the Spanish had already displaced many of the Indigenous people of the area). When Nina was not quite two years old, her father was shot and killed by an Anglo squatter who had moved on to the family’s land. A few years later, in 1886, her mother remarried. Alfred Maurice Bergere, who had family roots in Italy, was an Englishman who immigrated to the United States when he was sixteen years old. An Anglo, he was among those who moved west, arriving in New Mexico in 1880. Nina grew up in a household of twelve children, including her two younger brothers and her nine half siblings.

All of the Bergere children were educated. Nina attended St. Vincent’s Academy in Albuquerque until she was eleven years old, when she went to St. Louis Missouri to attend Maryville College of the Sacred Heart (now Maryville University) for two more years. She returned home to her family’s hacienda when she was 13. She helped educate her siblings and contributed to the work on the family ranch — experiences she recorded in her book, Old Spain in Our Southwest.

The family moved to Santa Fe in the New Mexico Territory when Nina was sixteen, after Alfred Bergere was hired as a judicial clerk.1 Nina became a regular fixture in the social life of the Santa Fe elite, described as “a graceful, intelligent young woman with an indomitable disposition,” and “high spirited and independent.” She met her husband, Rawson D. Warren, in 1907. Thirty five years old, he was the commanding officer of the Fifth US Cavalry stationed at Fort Wingate, near Gallup, New Mexico.2 Nina, who was 26 at the time, married Warren on June 25, 1908 becoming Nina Otero-Warren. After their Santa Fe wedding, Nina and Rawson moved back to Fort Wingate. Unhappy in her marriage, Nina divorced her husband after only two years, and returned to Santa Fe.

Since divorce was strongly frowned upon in both Anglo and Hispano cultures, Nina described herself as a widow, and kept Otero-Warren as her last name. She became active in New Mexico politics, and worked towards women’s suffrage. In 1912 she moved to New York City to keep house for her younger half-brother, Luna Bergere, who was studying at Columbia University. While in New York City, Nina volunteered at a settlement house in the city.3 When Nina’s mother died in 1914, she — the eldest daughter — moved back to Santa Fe, and as was expected of her, took over the household duties, which she took up as well as her activist work. Her suffrage work caught the attention of Alice Paul, who tapped Nina in 1917 to head the New Mexico chapter of the Congressional Union (precursor to the National Woman’s Party). Paul and other suffragists had realized that the support of Hispano’s in New Mexico was crucial to winning suffrage; Nina was an ideal choice. She insisted that suffrage literature be published in both English and Spanish, in order to reach the widest audience.

Nina certainly had enough family money that she did not have to work. And yet, in 1918, while still working for suffrage and taking care of her family, Otero-Warren took the job as Superintendent of Public Schools in Santa Fe County — a job she held until 1929, working to improve the conditions in rural Hispano and Native American communities. During this time, the federal government was pressuring for assimilation of non-whites, including Native American and Hispano people, into white America. This assimilation meant loss of traditional language, customs, and often family ties. As Superintendent of Public Schools, Nina worked to balance the demands of the federal government and her pride in her Spanish cultural heritage. For example, she argued that both Spanish and English be allowed in schools, despite the federal mandate of English-only. For a few years beginning in 1923, she was also appointed Santa Fe County’s Inspector of Indian Schools. She was angered by what she observed in the schools, and criticized the federal government’s Indian school system for the terrible conditions she observed.

In 1921, Otero-Warren ran for federal office, campaigning to be the Republican Party nominee for New Mexico to the US House of Representatives. She won the nomination, but lost the election by less than nine percent. She remained politically and socially active, and served as the Chairman of New Mexico’s Board of Health; an executive board member of the American Red Cross; and director of an adult literacy program in New Mexico for the Works Projects Administration.

Throughout her life, Nina was known both for her proper, mannered expectations of others and her unconventional personal life. Nina never remarried or had children of her own, but served as “La Nina” or godmother to her siblings, nieces and nephews, and arguably to her community. In the early 1930s, she and her partner Mamie Meadors — whom she had met in the 1920s — homesteaded, establishing a ranch called “Las Dos” (The Two Women) twelve miles outside of Santa Fe. They paid $67.40 for two homestead applications, and agreed to spend an average of five months a year living on their homestead, and to improve the land by building two houses, fencing the property (1,257 acres), cultivating the land, and maintaining the road for five years. Meeting these homesteading requirements, spelled out in the Homesteading Act of 1862, meant that they received title to the land. In 1947, Nina and Mamie established a real estate and insurance company, also called “Las Dos” in Santa Fe. When Mamie died in 1951, Nina continued running the business until her death. Whether their relationship was intimate is unknown, but they lived and worked together for over twenty years. Later in life, Nina was as a “regular annual apparition” at Santa Fe’s Hysterical/Historical parade with openly-gay poet, Witter Bynner.

It was in the 1930s that Nina took to writing. In May 1931, she wrote “My People” for an issue of Survey Graphic with the theme of “Mexicans in Our Midst: Newest and Oldest Settlers of the Southwest.” Other contributors to this issue included D.H. Lawrence, Ansel Adams, Diego Rivera, and Georgia O’Keeffe. Her book, Old Spain in Our Southwest was published in 1936.

Nina died on January 3, 1965 in the Santa Fe home she grew up in. She had been administering the property after the death of her brother two years’ prior.

Endnotes

- New Mexico did not become a state until 1910. The Alfred M. Bergere House, 135 Grant Ave, Santa Fe, New Mexico was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 1, 1975.

- -Fort Wingate Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 26, 1978.

- -Settlement houses were established by middle-class women in low-income urban areas. Settlement workers would live in the houses, with the goal of sharing knowledge and culture with their working class and poor neighbors. Settlement houses provided services like education, daycare, and health care for the communities in which they were located. One of the best known settlement houses in America was Jane Addams’ Hull House in Chicago.

Bibliography

- Historic Santa Fe Foundation. “A.M. Bergere House,” Historic Santa Fe Foundation.

- Las Dos, New Mexico. “The Homestead Legacy: Luna Bergere Otero Family.”

- Las Dos, New Mexico. “Las Dos: Two Women Homesteaders.”

- Massmann, Ann M. “Adelina ‘Nina’ Otero-Warren: A Spanish-American Cultural Broker.” Journal of the Southwest, Vol. 42, no. 4 (2000): 877-896.

- Morningstar, Amadea. “Nina Otero-Warren: A Graceful Non-Conformist.” The Santa Fe New Mexican, August 20, 1995.

- New Mexico Historic Women Marker Initiative. “Nina Otero-Warren.”

- Ybarra, Priscilla Solis. “Nina Otero,” New Mexico History.

Dr. Alice Paul

Significance: Fighter for women’s suffrage

Place of Birth: Mount Laurel, New Jersey

Date of Birth: January 11, 1885

Place of Death: Moorestown, New Jersey

Date of Death: July 9, 1977

Place of Burial: Cinnaminson, New Jersey

Cemetery Name: Westfield Friends Burial Ground

Alice Paul was one of the most prominent activists of the 20th-century women’s rights movement. An outspoken suffragist and feminist, she tirelessly led the charge for women’s suffrage and equal rights in the United States. Born to a New Jersey Quaker family in 1885, young Alice grew up attending suffragist meetings with her mother.1 She pursued an unusually high level of education for a woman of her time, graduating Swarthmore College in 1905. She also received her master’s in sociology in 1907, a PhD in economics in 1912 from the University of Pennsylvania, and a law degree (LLB) from the Washington College of Law at American University in 1922.

While continuing her studies in England, she made the acquaintance of militant British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, Christabel and Sylvia. Pankhurst’s group used disruptive and radical tactics including smashing windows and prison hunger strikes. Police arrested and imprisoned Paul many times for her involvement with the group. Forever changed by her experiences, Paul returned to the United States in 1910 and turned her attention to the American suffrage movement. After the deaths of Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1902 and Susan B. Anthony in 1906, the suffrage movement was languishing, lacking focus under conservative suffrage organizations that concentrated only on achieving state suffrage. Paul believed that the movement needed to focus on the passage of a federal suffrage amendment to the US Constitution.

When she first returned to the United States, Alice Paul attempted to work with the main US suffrage organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). They appointed her chair of the NAWSA Congressional Committee in 1912. Almost immediately, she began organizing a Woman Suffrage Procession planned for Washington, DC, on March 3, 1913 — the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. The carefully planned parade turned into a near riot when spectators began assaulting the women and the police refused to intervene. The cavalry from Fort Myer eventually restored order and the parade continued. Disagreements over the parade and fundraising lead to growing tension between Alice Paul and the NAWSA leadership.

In 1916, Paul founded the National Woman’s Party (NWP). Paul adopted the Pankhursts’ imperative to “hold the party in power responsible.” The NWP withheld its support from existing political parties until women had gained the right to vote and “punished” those parties in power who did not support suffrage. Through dramatic protests, marches, and demonstrations, the suffrage movement gained popular support.

In 1917, Alice Paul and the NWP began picketing the White House — the first time ever anyone had protested there. When World War I started, people felt that the nonviolent protests by these “Silent Sentinels” was disloyal. The women were harassed and beaten, and were repeatedly arrested and jailed on charges of “obstructing traffic.” The women were sent to the Occoquan Workhouse (prison) in Virginia and the District Jail in DC.2 Prison conditions were awful. In October 1917, Alice Paul and others went on a hunger strike in protest. In response, the prison guards restrained and force-fed her through a tube. In November 1917, the superintendent of Occoquan ordered over forty guards to attack the Silent Sentinels. Battered, choked, and beaten, some to unconsciousness, the women described it as the “Night of Terror.”

Nevertheless, Paul and the NWP continue to organize protests outside the White House until 1919, when Congress voted to send the Susan B. Anthony Amendment to the states for ratification. In 1920, the required 36 states ratified the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, making it the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution. The 19th Amendment paved the way for most women to vote by removing sex as legitimate legal reason to deny a woman the right to vote.

Paul believed the vote was just the first step in the quest for full gender equality. In 1922, she reorganized the NWP with the goal of eliminating all discrimination against women. On July 20, 1923, 75 years after the first women’s rights convention in 1848, Paul introduced the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), also known as the Lucretia Mott Amendment, in Seneca Falls, NY.3 It launched what would be a lifelong campaign to win full equality for women. In 1929, the National Woman’s Party moved into a permanent headquarters in the Sewell House on Capitol Hill. The NWP renamed the house the Alva Belmont House in honor of their primary benefactor.4

Concerned not only with the rights of American women, but also with those of women around the world, Paul founded the World Woman’s Party, which served as the NWP’s international organization until 1954. In 1945, she was instrumental in incorporating language regarding women’s equality in the United Nations Charter, and in establishing a permanent UN Commission on the Status of Women. In the 1960s, she also played a role in getting sex included in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that prohibits discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Alice died in 1977 at a Quaker facility in Moorestown, New Jersey. She is remembered as a tireless, devoted pioneer in the fight for women’s rights, and her legacy is still felt by women around the world today.

Endnotes

- Alice Paul’s birthplace, known as Paulsdale, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 5, 1989 and designated a National Historic Landmark on December 4, 1991.

- The Occoquan Workhouse was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as part of the DC Workhouse and Reformatory Historic District on February 16, 2006.

- Women’s Rights National Historical Park preserves the sites associated with the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, NY.

- The building that the NWP moved in to is the oldest standing building in the Capitol Hill area. Known as the Alva Belmont House and the Sewell-Belmont House, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 16, 1972, and designated a National Historic Landmark on May 30, 1974. It was designated the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, a unit of the National Park Service, on April 12, 2016.

Jeannette Rankin

Significance: First woman to hold federal office in the US; Politician; Women’s Rights Advocate

Place of Birth: Missoula County, Montana

Date of Birth: June 11, 1880

Place of Death: Carmel, California

Date of Death: May 18, 1973

Place of Burial: Memorial only: Missoula, Montana

Cemetery Name: Memorial only: Missoula Cemetery

I want to be remembered as the only woman who ever voted to give women the right to vote. -Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Rankin was born on June 11, 1880 on her parent’s ranch near Missoula, Montana. She was the oldest of six children. Her parents, John (a Canadian immigrant) and Olive Rankin had traveled to Montana in search of gold. They later established their ranch and became successful business people. In the 1890s, under the Homestead Act of 1862, the Rankins added another 160 acres to their ranch.

While growing up, Rankin worked on her family ranch. Her jobs included farm and household chores, maintaining machinery, and helping build things. Later she recalled noticing that, while frontier women and men worked the land side by side “proving up” a homestead as equals, they did not have equal access to the vote.

Rankin graduated with a biology degree from the University of Montana in 1902. Her travels took her to San Francisco, New York City, and Spokane, Washington. She became involved in the women’s suffrage movement while at the University of Washington. She helped to organize the New York Women’s Suffrage Party and worked as a lobbyist for the National American Woman Suffrage Association. In February 1911, she returned to Montana, and became the first woman to argue for women’s suffrage in front of the state legislature. In November, 1914, Montana granted women unrestricted voting rights. The suffrage amendment had its largest support from the homestead counties in the eastern portion of the state. Montana had a particularly high number of women homesteaders, as its settlement coincided with larger numbers of women choosing to homestead in the twentieth century.

In 1916, Jeannette Rankin became the first woman in US history elected to the House of Representatives. This was remarkable because most American women were not able to vote until the 19th Amendment passed in 1920. She was a member of the Republican Party. She was the first federally elected woman in the United States elected at the age of 36 to the U.S. House of Representatives as one of two congressional representatives for Montana.

Rankin did not believe that war was a good way to solve conflicts. On April 6, 1917, four days after being sworn in to Congress, she voted against the United States getting involved in the World War (World War I). “I wish to stand for my country,” she said, “but I cannot vote for war.” The vote generated much ill will, and she was not re-elected in 1918. During her tenure in Congress, however, Rankin did vote to give American women access to the ballot box.

After leaving Washington, DC, she moved to a small farm in Georgia. Her home did not have electricity or plumbing. She continued to work for peace, giving speeches for the Women’s Peace Union and the National Council for the Prevention of War. She also worked for social change. She worked to ban child labor and to increase the welfare of women and children. Though she owned the farm in Georgia, her regular summer home from 1923 through 1956 was her brother’s property, the Rankin Ranch in Broadwater County, Montana.1

In 1940, at age 60, Rankin ran again for a seat in the House of Representatives. She won, and was appointed to the Committee on Public Lands and the Committee on Insular Affairs. On December 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Rankin cast the only vote in Congress against the US declaration of war against Japan. “As a women I can’t go to war,” she said, “and I refuse to send anyone else.” Her vote against US involvement in World War II once again cost her any chance of re-election.

After leaving Congress for a second time, Rankin returned to private life. But in January of 1968, she again returned to Washington, DC. This time, instead of sitting in Congress, she led a march of 5,000 against the Vietnam War to the steps of the US Capitol. Her passion for peace earned her the nickname, “the original dove in Congress.”

Jeannette Rankin never married. She died in 1973. A memorial stone to her stands in the Missoula Cemetery. She left her estate to help “mature, unemployed women workers.”

Endnote

- 90 acres of Rankin Ranch was added to the National Register of Historic Places and designated a National Historic Landmark on May 11, 1976.

References

- O’Brien, Mary Barmeyer. 1995. Jeannette Rankin, 1880-1973: Bright Star in the Big Sky. Helena, Montana: Falcon Press.

- Shirley, Gayle C. 1995. More Than Petticoats: Remarkable Montana Women. Helena, Montana: Falcon Press.

- United States Congress. 2019. Rankin, Jeannette, (1880-1973). Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

Tye Leung Schulze

Significance: First Chinese voter; community activist

Place of Birth: San Francisco, California

Date of Birth: August 24, 1887

Place of Death: San Francisco, California

Date of Death: 1972

Place of Burial: Unknown

Tye Leung was a civil rights and community activist born in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1887. Like many in the neighborhood, her family was not rich and the house was crowded. She lived with her parents, 7 siblings, and her elderly aunt and uncle. Growing up, she and her siblings experienced segregation at an early age: local law forced Chinese Americans into separate schools. After elementary school, there were few options for a girl like Leung. She found a place, however, at the Presbyterian Mission under the tutelage of Donaldina Cameron, a teacher and local activist.

In 1899, her parents arranged a marriage for Leung’s older sister to a much older man in Montana. Not willing to accept this match, her sister ran away with her boyfriend and left their parents in a tight spot. Unfortunately for Leung, her parents’ solution was for 12- or 14-year-old Tye Leung to take her sister’s place (sources differ on her age). Resisting, Leung ran to the only place that she felt safe: the Presbyterian Mission. Cameron regarded Leung as an escaping slave, and provided a new place for her to live and learn. Soon, Leung became a star pupil of Cameron’s and worked with her as a translator and interpreter in court as the Mission worked to free Chinese women from sex slavery.