By Dr. Patrizio Pensabene

Professor of Archaeology Emeritus

Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”

Abstract

This paper is a historical outline of the practice of reuse in Rome between the 4th and 5th century AD. It comments on the relevance of the Arch of Constantine and the Basilica Lateranensis in creating a tradition of meanings and ways of the reuse. Moreover, the paper focuses on the government’s attitude towards the preservation of ancient edifices in the monumental center of Rome in the first half of the ǣth century AD, although it has been established that the reuse of public edifices only became a normal practice starting in Ǥth century Rome. Between the 6th and 8th century the city was transformed into settlements connected to the principal groups of ruins. Then, with the Carolingian Age, the city achieved a new unity and several new, large-scale churches were created. These construction projects required systematic spoliation of existing marble. The city enlarged even more rapidly in the Romanesque period with the construction of a large basilica for which marble had to be sought in the periphery of the ancient city. At that time there existed a highly developed organization for spoliating and reworking ancient marble: the Cosmatesque Workshop.

Introduction: The Role of Deichmann in the Light of New Research on Reuse

Sources from late antiquity have handed down a notable number of descriptions of churches, which often cite as a characterizing element the ‘forest of columns’(selva di colonne): thus in his solemn report on the basilica in Tyre, Eusebius took the trouble to describe columns, fountains and four-sided porticoes and briefly mentioned the sculptures of the central gate and of the ceilings, but he ignored the iconographic figures; and when Saint Jerome wanted to express his indignation at luxury in churches, in the first place he railed against marble, gold and precious stones and did not mention paintings or other elements.1 In fact a characteristic of churches since late antiquity has been the role assumed by the columns and marbles of the elevations, which transcend their architectural meaning in as much as they express less a need for luxury, as Saint Jerome claimed, than the continuity of the Roman decorative tradition and therefore of the prestige attached to it, though with new Christian meanings.

To understand these meanings it has been necessary to study the modes of the different layouts of spolia elements in mediaeval churches in Rome all the way back to the origins of Christian architecture and to the moment when the prestigious models of the imposing basilicas were established: these latter, though they were directly or distantly reproduced by mediaeval churches, with all the attendant historical implications, do form a continuous point of reference.

It was Friedrich Deichmann who, in a kind of precursor role, in 1940 first considered in a systematic way the set of historical problems raised by reuse in early Christian and early mediaeval architecture. The content of the article, which was very slowly accepted into the history of the discipline, was then elaborated and developed by the author himself in 1974. Beginning with the distinction between ancient pieces as mere building material (a phenomenon widely diffused everywhere and in every age) and the reuse of worked pieces with the aim of producing an aesthetic effect (a phenomenon found almost throughout the whole Mediterranean world from the age of the tetrarchs), Deichmann managed to outline the criteria for the display of columns and other architectural spolia. Whatever may be their validity in the light of more recent studies, it is still Deichmann’s merit to have stated that the criteria adopted in the positioning of the different pieces to be reused in churches were not casual. Although in most cases each building has a precise, peculiar logic, we can recognize the aim to use similar shafts as far as possible and, to achieve a certain homogeneity, an arrangement in opposing pairs or longitudinal sequences.

We now know that it was in Constantine’s basilicas that for the first time these criteria for placing spolia were expressed in a systematic way, but it is also known that the criteria did not remain unchanged through the Middle Ages, in as much as they changed according to historical circumstances, to the understanding of ancient architecture and to the ways it functioned inside the new churches.

We here briefly indicate the modes of displaying the columns:

- Pairings or longitudinal sequences: the same or similar elements were placed in only one of the colonnades;

- Symmetrical contrapositions (transversal axes): the same or similar elements correspond in the same position with each other in both colonnades;

- Diagonal crossings: to the elements of a column in a nave correspond other elements equal or similar in the parallel nave, but not in a symmetrical position or,at most, brought forward or backward by two places. Though scarcely used, such a system acquires particular importance if it is interpreted as a symbol (in fact it reproduces a cross).

The use of these schemes may be aimed at satisfying different demands:

- To distinguish areas intended for different functions inside the building: for in-stance in S. Agnese the chiastic placement of the sixth and seventh pair of columns(preceded by two shafts of fluted pavonazzetto) is used to mark the perimeter of the presbytery; in the cross scheme, rather than using different materials, they in-stead used different varieties of the same marble, probably in order not to create an excessive lack of homogeneity.

- To highlight the presence of a particular element of the building such as the Triumphal Arch or the Schola Cantorum: in S. Pietro in Vincoli the change of order from Doric to Corinthian serves to indicate the Triumphal Arch whilst in S. Giovanni a Porta Latina the two last fluted columns are meant to highlight the choir.

- In round churches to define with different materials the main axis or the direction of a route: for instance, in S. Costanza the shafts in pink Syene granite and grey granite may have had the function of leading towards Costanza’s sarcophagus.

Deichmann insisted that one has to exclude that classicistic movements determined the usage of spolia, as the phenomenon was not limited to Rome only and the ancient pieces were set into a far from classical context, in which a reversal of the legitimate orders or the mutilation and reduction of their elements is found.2 He also believed that looking at the reused pieces as evidence of an ancient grandeur, not only artistic but also political, or even a symbol of the triumph over paganism, couldn’t be considered to be the origin of the phenomenon. We are dealing here with interpretations that, despite their grandiose effects, were given a posteriori.3

Now, several decades since Deichmann published his theories, which did not refer to the city of Rome alone and were chronologically limited to the period between the fourth and the seventh century, we believe that they must be considered in the light of a more comprehensive evaluation of the individual monuments and of the available material. Along these lines the more recent studies on reuse in the Lateran Basilica (of the Saviour) and in St. Peter’s have proved to be more useful, as they show that in their colonnades not only spolia are present but also new materials, which were employed together with reused pieces. In this way they offer the opportunity of not reducing the problems of reuse to mere economics, but of taking into account other aspects such as the patrons and the construction times, which, if short, demanded the collection of larger quantities of spolia, a choice due to the building policy and not determined by the need to save money. If the starting point in each case is an inquiry into the function of the reuse within basilica areas, then the motivation and planning, which derive from the model of the vast early Christian basilicas in Rome, remain unchanged. Here it was the presbytery area with the tabernacle that made necessary the use of columns for the naves, which thus appear like a kind of via triumphalis leading towards the huge arch preceding the presbytery.

It should be underlined that there are two problems to bear in mind every time one faces a problem of reuse in the field of architecture. On the one hand there is the question of the source supplying the materials and the historical and economic conditions that caused changes each time; on the other, the modes for placing and using the material itself, once again in relation to the multiple historical and economic factors,though also artistic and ideological ones, which in a more or less decisive way deter-mined the different choices.While Deichmann developed his line of thought mainly in relation to the modes of placement, he chose to give less attention to the historical-religious, historical-economical and, depending on the period, more-or-less ideological data, which are anything but irrelevant for the aim of a comprehensive and well structured assessment of the phenomenon itself.

The phenomenon of the reuse of ancient material from the third to the twelfth century has been the subject of a large number of studies, and in particular of specific cases, to the extent that one again feels the need to start updating the studies themselves to take into account the historical data and the results of the most recent research on ecclesiastical buildings. The vast extent of the phenomenon (both chronologically and geographically), the difficulty of retrieving a sufficient quantity of objective data, the need to consider the multiple motivations which determined it in each case and, not least, the “rigid separation of the disciplines of archaeology and of the history of art”4 have represented obstacles to an interpretation that would stay as close as possible to the historical reality of the phenomenon under study.However, from the historiographic point of view, as P. Fancelli observed in 2000,5 the problems of spolia have reached an‘authentic mature stage’ which allows one to draw conclusions and to understand the assumptions underlying the direction or directions taken by the studies.

The contribution offered here is stimulated by the specific need to set the phenomenon of reuse in Rome into the history of the city, linking it closely to its urban and architectural transformations: we shall try to place – as far as is possible in a synthesis – the processes of spoliation and of reusing architectural materials within the historic context in which they took place, maintaining as a leitmotiv the reflections on the ways used to display the spolia in the churches, which derive from Deichmann’s studies.

Fourth to Fifth Centuries

More than once it has been pointed out that the first Christian basilica, St. John’s Lateran, with five naves and at first without a real transept,6 represents a voluntary imitation of the model of the lay imperial basilica,7 indeed perhaps of the Basilica Ulpia itself, similar both in size (more than 100 meters in length) and partly in plan (five naves but with two apses on the short sides). A voluntary imitation, it has been said, since it turns out that the choice fell on the forum basilica not only to obtain rapidly a building that could welcome large numbers of the faithful, but also for the ideological and propaganda meaning that such a choice endorsed. It seems to us that Constantine was expressing a personal political program linked to the great tradition of imperial euergetism, and perhaps ideally to Trajan with whom he wanted to be compared. On the other hand, but still within this tradition, Constantine was also countering the pagan buildings of the center with the new building with its Christian meaning and position at Rome’s periphery. Better still, as Krautheimer noted, the city became surrounded by grandiose cemeterial and circus-like basilicas such as St. Peter’s, S. Lorenzo fuorile mura, S. Sebastian and the basilica in the area of S. Agnese,8 which represented a Christian Rome around the pagan one.9

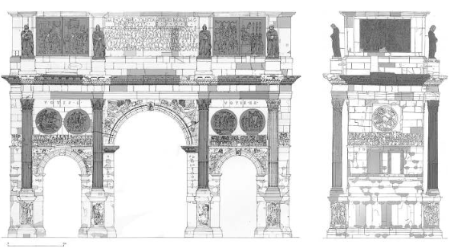

In that direction too ran the analogous ideological desire represented on the Arch of Constantine of wanting to connect it to the great Roman tradition of triumphal arches, though in this case in order to celebrate victory in a civil war and not against external enemies of the empire (Fig. 1). The arch itself provided a framework of normality for this ‘unusual’ victory not only by means of the faithful imitation of the architectural prototype of Septimius Severus’ arch, but also by putting together or – better – mixing reused friezes and reliefs with those worked ex novo. The former showed the representation of the traditional and classical imperial virtutes, the latter narrated on the friezes the vicissitudes of Constantine’s war and the ways, once he was back in Rome, of expressing his own virtutes and stressing the framework of ‘normality’ through reliefs with barbarian prisoners and trophies, representing also victories and the genii of the seasons – a hint at his everlasting victory. The old interpretation may today seem antiquated, which saw in the reuse of reliefs representing the ‘good emperors’ of the second century AD the announcement of a political program, since the distance from them was bridged by the substitution of the emperors’ head with Constantine’s. Nowadays the prevailing interpretation sees the reused reliefs as the expression of patrons who want to present Constantine as the heir to the best military traditions and to imperial government through the repetition of images where he is the actual protagonist. Of minor importance, then, would be the possible consciousness of being in the presence of reused materials originally portraying the ‘good emperors’: what is important is not the moment when the reliefs were made, but the period and modes of the reuse, and it is from here that a clear political program emerges which can easily be read on the arch.10

These remarks can perhaps be extended also to the interpretation of the aims in the choice of the spolia to be used in the new Christian monuments which, then, carry messages of decus, prestige, of closeness to the imperial architectural traditions, but which do not recall the past in an ideological key. But the particular situation of Rome in Constantine’s time must have influenced the choice of using mainly spolia (on the arch even the reliefs worked ex novo came from reused marbles) and not marble blocks or brand new shafts, as well as the heterogeneity of the marbles, of different qualities and colors and seldom identical. In the first place this was a time when they did not have the opportunity to reuse large quantities of homogeneous material, since most of the public buildings were still standing: only the latter could provide architectural elements of the appropriate dimensions for the new and huge Christian basilicas. This new way to use architectural elements, characterized by the lack of homogeneity of the order (for instance the use of Corinthian capitals different from each other) and/or of the orders in-side each room, brings about new ways for their placement and at the same time a kind of new architectural aesthetics, which was treated for the first time by Deichmann.11 On this point it suffices to mention the arrangement of the shafts in opposed pairs, based on the stone color in the central nave in St. Peter’s where, besides, the transept differs from the naves because of the use of the composite capital, which will be so influential during the fourth century on the choice of the capital order of the architectural sarcophagi and in the capitals of the domus built at that time, as is the case in Ostia.

This heterogeneity was, then, motivated by the impossibility of having at one’s disposal similar marble elements of large size. The Mausoleum of S. Costanza shows that when it was possible to obtain architectural pieces from the same source of supply, a substantial uniformity in the use of the architectural orders was achieved. In the Mausoleum the cupola drum stands on a double ring of marble columns from spolia, on which were reused two types of composite capitals: from the Augustan age12 towards the inside, and from the Severan age towards the outside, with the exception of one single Corinthian capital. The columns in granite can also be considered uniformly placed.13

The small size of the capitals in S. Costanza suggested that the greater uniformity of the architectural order in the Mausoleum was enabled by easier availability of uniform reuse-pieces from a private or civil building of small size and for some reason no longer in use.14 To the contrary, the material available for the grandiose Christian basilicas in Rome would not have offered a large number of uniform pieces and must have been determined by casual factors: collapses due to earthquakes, warehouse stocks in Rome, in important provincial cities or at the quarries, or large suburban buildings no longer in use.

We have here met changes in both architectural taste and tradition, which were made possible because the foundation of new capital cities, and soon of Costantinople, had elsewhere stocked up marbles directly from the quarries and assembled workers more expert in crafting them. Therefore in Rome huge financial investments ceased to erect new public buildings, which would have permitted the presence and continuity of craft workers specialized in working marbles and who could have handed on the imperial decorative tradition. In fact, after Constantine’s age the known examples of capitals and of other architectural elements represent an attempt at a classicistic resumption of traditional types rather than continuity, a fact that brings about the creation of new forms such as the composite capitals with smooth leaves.15 Such a situation had not happened in Rome since the Augustan era, for although throughout the whole imperial age the typological particulars had changed often in connection with the changes and speeding up of the crafting processes, the essential forms of the elements of the orders had not changed. Apart from restoration works and what were in effect remakes, such as the Porticus of the Dei Consentes and the Temple of Saturn, the only large public buildings built in the fourth century are the Christian basilicas: Constantine’s building activity is limited to the completion of sites already begun by Maxentius who had been the last great builder in Rome.16

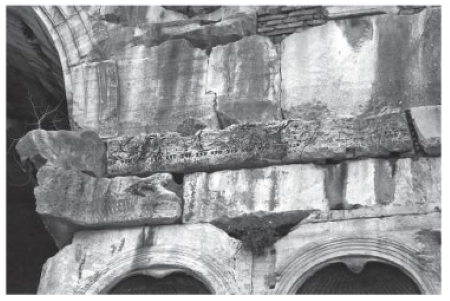

But what strikes us about the reuse both in the Arch of Constantine and in the Lateran Basilica and in St. Peter’s, as well as in the previous monuments of the tetrarchs and Maxentius, is the size of the column shafts, bases and reused capitals. That implies the availability of marble spolia presumably from public or at least imperial monuments, given their size and the quality of their craftsmanship. Though we are still in an age when the city in its monumental area was certainly almost all still standing, yet precisely because of the number and size of the reused shafts in the large Christian basilicas, we conclude that warehouses had been set up, probably owned by the government, where, as we have already said, the remains had been collected of buildings that had been damaged in some natural event (earthquakes, fires) or parts of monuments unfinished for a number of reasons, such as damnatio memoriae, adaptations or changes. Along these lines the hypothesis has been put forward that some of the architectural marbles came from the leftovers of Maxentius’ reconstruction of the cells and colonnaded porticoes of the Temple of Venus and Rome, which had shortly before been damaged in Carinus’ fire and which on the occasion of the reconstruction underwent the partial elimination of the internal colonnade of the peristyle: certainly from this temple are some architectural elements reused in Maxentius’ basilica.17 Moreover the provenance of the Dacians on the Arch from Trajan’s Forum is no longer certain, since none of the same dimension have been discovered in the forum and since fragments of semi-worked statues in pavonazzetto have been found in marble warehouses connected to the river harbour near the Campus Martius.18 In fact the textad arcu(m) engraved on the base of the Dacians of Constantine’s arch suggests that they had previously been placed in a warehouse, where they could have been selected, rather than – possibly –on the forum porticoes, for which the inscribed indications of the intended use would have caused greater difficulties, especially if the statues were placed on the attic.19 We may recall that even in the Arch of Janus a block of travertine in the floor was reused, on which the ARCI mark was engraved and which may represent an indication of its intended use.20 Both arches, that of Constantine and that “of Janus” (probably to be identified as the Arch of Divus Constantinus)21 already pose the problem of the existence of a large public building whose entablature must have already been abandoned, since in both arches elements of frieze/cornices and other parts of the entablature were reused (Fig. 2).

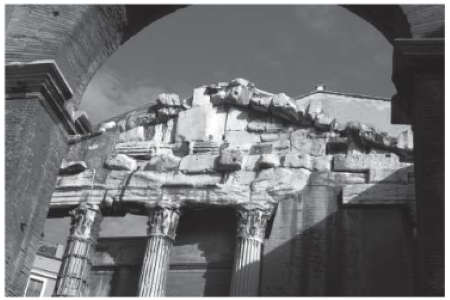

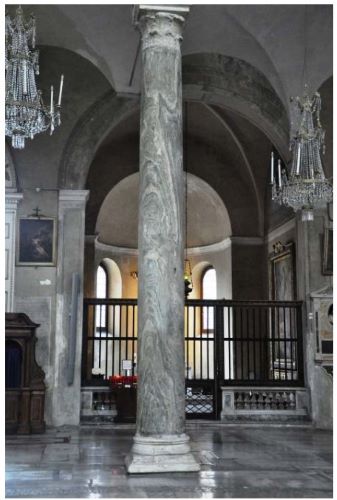

This fact presupposes an origin in important monuments, such as the Arch dedicated to Marcus Aurelius, from which may have come the reliefs on the attic of Constantine’s arch. Again, reused sections of trabeations, bases and column drums of noticeable size have suggested a provenance of some of their spolia in the Temple of Venus and Rome but also in some temple compound in the Campus Martius; we refer, in particular, to the threshold of the south side of the central vault of the Arch of Constantine, which consists of a huge lintel block of Proconnesian marble (5 m long, 1.40 m wide) and in another one, next to it but smaller, for which a provenance from the Temple of Matidia in the Campus Martius has been proposed.22 It is also known that the surviving honorary columns on the south side of the Roman Forum, which can be dated on the basis of the brick seals to the age of Diocletian or between Diocletian and Maxentius,23 consisted of huge reused shafts (the cabled ones in pavonazzetto, the fluted in white marble, the smooth in grey or pink granite from Syene), which once again would indicate an origin in grandiose buildings. Also the column of Phocas (Fig. 3), the main phase of which is from the age of Diocletian or from the fourth century (during the phase of its re-dedication in 608 only the steps on the four sides were added),24 consisted of one large Corinthian capital from the time of Trajan and a fluted shaft in Proconnesian marble (13.60 m high), divided up in drums that also date to the high imperial age. If already in the first decades of the fourth century there were thus large drums of fluted columns in Proconnesian such as those of Phocas’ column available for reuse, it is no wonder that we find a drum with a 1.85 m diameter reused in the brickwork of the Arch of Janus.25

Moreover, it has been thought that indeed the ‘Trajan’ friezes reused in the Arch of Constantine may be Domitianic because it is believed almost impossible that Trajan’s Forum would have been impoverished to the advantage of the Arch of Constantine, whereas Domitian’s damnatio memoriae may have left monuments dedicated to him unfinished and their marbles kept in warehouses.26 Other hypotheses may be possible, because it has already been noted that one of the composite capitals of the portico in summa cavea of the Colosseum reconstructed under Alexander Severus was sculpted asa single reused marble block with a section of a large inscription which has been recognized as a dedication to Trajan,27 therefore suggesting the existence of a monument to Trajan already demolished or not finished, whose architectural elements could have been reused already at the end of the Severan age.

What is certain is that, during the course of the fourth century and mainly in the first half of the fifth century, the government’s attitude towards the preservation of the ancient buildings of the monumental centre in Rome was not uniform. While on the one hand there are several restoration works in the area of the Roman forum, on the other hand an early abandonment of some monumental buildings such as the Temple of the Dioscuri has been noted. It has been proposed that structural issues had endangered the stability of this temple and of other structures, causing an untimely abandonment and the subsequent removal of some parts in marble. Moreover, it has been pointed out that the building of the Rostra Diocletiani must have ‘cut out’ of the Forum the temples of Castor and Pollux and of Divus Iulius. Their maintenance was therefore either neglected or interrupted, condemning them to a decline, evident from the middle of the fourth century, contrary to what happened to the Curia and the Basilica Iulia, which were reconstructed after the fire of 285,28 and of the Temple of Saturn and the Porticus of the Dei Consentes, which were restored towards the end of the fourth century.29 In fact a hostile attitude towards the pagan monuments in Rome and even to shrines for ancient cults did not immediately emerge. There was a series of gradual legal initiatives, which became more frequent and decisive in their anti-pagan content only at the end of the fourth century when the Theodosius I’s various decrees (see in particular that of 391) give evidence of a new phase, definable as repressive, towards the ancient temples, and also dictate criteria for the preservation of ancient buildings. The Theodosian period is also important for the fact that the government and the bishops progressively began to share common intentions and show solidarity with each other regarding pagan buildings.30

From the fifth century onward, apart from works of public utility such as aqueducts and baths or places of public entertainment such as buildings for the performing arts –which were being restored – many other ancient structures were abandoned since they had lost their original role: almost always they were reused, either by removing single parts, preferably pieces already crafted, or columns to reuse in new edifices, or by reusing the entire ancient building for a different purpose.

But it is from the sixth century that we find as a ‘normal’ activity the reuse of public buildings (and not only of temples), and – after the wars against the Goths which had devastated Italy – the availability of lands and money from the Church, in a larger quantity than from the Byzantine government itself, which proposed in consequence that the care and administration of many buildings passed to the Church itself.31 It should be pointed out, however, that the laws in late antiquity had never prescribed the systematic transfer of public buildings to the Church, although that does not exclude that they may have been the objects of specific acts of donation. It has been ascertained, however, that the actual controls by the authorities disappear with the sixth century32 and that the diversions of the fundi templorum went completely to the benefit of the sacrae largitiones soon after 423, as one can infer from the Theodosian Code.33

Both the archaeological data and the laws offer the chance to follow the transformations taking place, by providing evidence of the removal of the spolia and consequently the partial or complete abandonment of public buildings, which began to increase infrequency from the late fourth century. An area within the city that seems to be affected in that sense is again the Campus Martius: the long succession of inundations by the Tiber, of earthquakes and finally the Visigoths’ pillaging seriously damaged the structure of some buildings. This triggered a process of transformation, destined to last also for the following two centuries, which began with the change of purpose of the Porticus Minucia Frumentaria, whose area was crossed by a road, and ended up with the creation of ecclesiastical structures in the area of the four temples of Largo Argentina, that is, the Boetianum monastery and the Church of S. Nicola de Calcarario and within the Porticus itself, the Xenodochium Aniciorum.34 The topography of the Campus Martius must have been altered extremely when at the wish of Pope Damasus (266-384) a system of porticoes was built, the Porticus Maximae leading from the theater of Balbus to the Pons Aelius.35

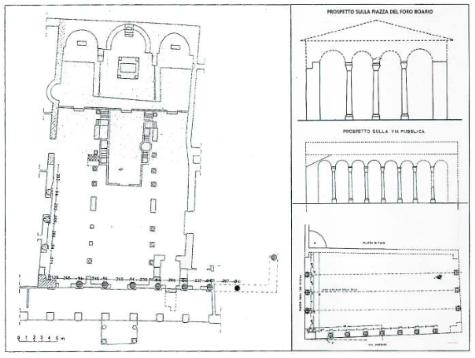

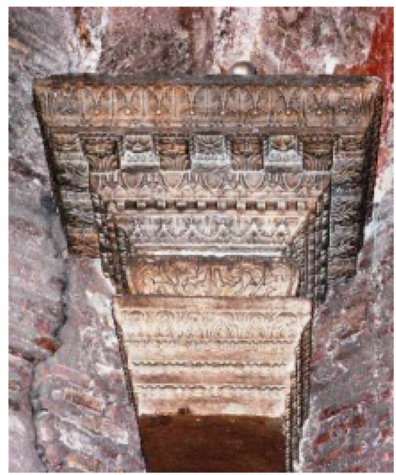

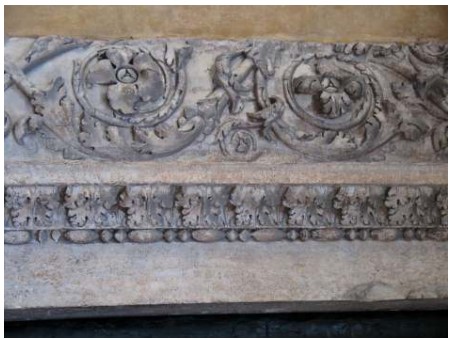

Within that context we can understand how from the propylaea of the Porticus of Octavia (Fig. 4), which belong to the Severan restoration of the com-pound,36 three capitals (Fig. 6) and probably other marbles were removed to reuse them in S. Paolo fuori le mura either in the late fourth century or, more likely, on the occasion of the extensive works of the fifth century, i.e. later than 441, under St. Leo the Great (440-461): three Corinthian samples reused on the columns of the central nave of the basilica match the five capitals still in situ (Fig. 5) in the propylaea, which were once tetrastyle (two capitals on the outside façade and three on the inside one), with a pediment on both sides.37 Although mainly during the course of the fourth century and also, to a minor extent, in the first half of the fifth we notice the only partial demolition of ancient buildings, as the preservation until now of the façades of the Porticus of Octavia would prove (Fig. 4), it is probable that starting from the years immediately after the 410 sack of Rome, entire monumental compounds became available, evidently since they had been damaged and were not salvageable, or at least not restored for the lack of political will with this aim.

At the same time as a larger availability of elements for reuse in the fifth century there emerge utterly changed attitudes towards ancient buildings, which are expressed in Theodosius’ law of 435 prohibiting all the pagan cults and encouraging the destruction and transformation of temples into churches, ordering, among other things, different forms of exorcism and purification by means of engraving crosses.38 It is the time of exceptional destruction of temples by the Christian population and the bishops.39 In any case, given the changes which had taken place in the fourth century (though in the first half of the fifth there was a more diffused uniformity in the employment of architectural spolia), the practice – by now the expression of a new taste – continued of highlighting different areas of a church by a change of orders or of the colour of the columns.

In Rome an indicative example is S. Pietro in Vincoli, built as a joint commission of the emperor’s family and the pope in 430, where in the central nave were reused fluted columns and matching Doric capitals of the same white greyish marble (Parian from the Marathi quarries?) probably from a building nearby, perhaps the Porticus of Livia, which was already abandoned. The ‘triumphal arch’, instead, which separated the nave from the presbytery, is supported by Asian Corinthian capitals on columns in grey granite. This building was promoted by the pope and by Eudocia, an imperial euergetes, which accounts for the permission to demolish and reuse a whole porticoed compound.

Fig. 8: S. Sabina: right nave.

The almost contemporary case of S. Sabina can also be cited (Fig. 8): it was built by the bishop Peter of Illyria, who was close to the papal milieu, reusing almost entirely the architectural elements obtained by the demolition of one building, probably the Baths of Sura (perhaps situated north of S. Prisca).

They did not hesitate – or they did not have any sensitivity about the issue – to reuse cornices or elements of cornices as the doorpost of one of the side doors: the naves are supported by cabled columns and Corinthian capitals (Fig. 9), all similar in white marble, and the central door reuses the doorposts of the building from which the elements derive;40 the entablature and the walls supported by the columns are covered by precious marble slabs, forming an opus sectile in the coloristic taste of late Roman architecture.

Again in S. Paolo fuori le mura during the restoration works in 441, already mentioned, 24 of the 40 columns in the naves were substituted with magnificent shafts in pavonazzetto, for which a provenance from Hadrian’s Mausoleum was stated by Nicola Nicolai, drawing upon Piranesi, Nicolai being the most important source on the condition of the church before the 1823 fire (Fig. 7). In 1815 he also described the columns (24 monolithic columns in pavonazzetto, fluted from one third upward) and added a drawing of two of them (10.19 and 10.45 m high).

We have to point out, though, that the Ionian capitals, not preserved but known from historical sources, in S. Maria Maggiore and those in S. Stefano Rotondo from 467 – these latter probably depending, in their form, on those in Santa Maria Maggiore – and of the Triumphal Arch in S. Paolo fuori le mura (the model of this late revival of the production of Ionian capitals must have been Diocletian’s Baths and the Temple of Saturn), show that in the fifth century it was difficult to find in Rome a number of capitals to be reused and placed in the same church. Therefore, when the ‘classicist’ need to use only one order was felt and when the historical circumstances of the patrons permitted (see the period of Sixtus III), for a new building there was a recourse to capitals worked ex novo and sculpted in Rome throughout the whole process. Reused marble elements were also employed to be newly carved; we may cite the Ionian capital of the Antiquarium on the Caelian Hill, found in the excavation near the Chiesa Nuova, which has been sculpted from a reused architectural block. But we also have the evidence of semi-worked capitals kept in the warehouses where pieces from demolished buildings were collected, or in the huge storehouses for the marbles along the Tiber, near the Statio Marmorum at the foot of the Aventine and at Porto. Here, as we have already observed in other studies, there were remains, in rather large quantities, of marble blocks and shafts that had never been set in place, often imported even in previous centuries and left unused; here Ionian and Corinthian capitals still arrived from eastern quarries that specialized in this kind of product (Proconnesus, Thasos, the Mani in the Peloponnese).41 We can also put forward the hypothesis that the preference, which we find for Ionian capitals was due to the fact that it was easier to carve their decorative elements than the acanthus leaves and other vegetal elements of the Corinthian and composite orders.

These warehouses and storehouses continued to supply ecclesiastical building sites even in the late fifth century, as attested by many of the granite shafts in S. Stefano Rotondo with unfinished scapes (extremities / scapi) (Fig. 10) and with initials on some of its architectural elements, to be interpreted as abbreviations of the proprietor or of the warehouse managers.42

The same evidence is also offered by the large group of Corinthian capitals with denticular acanthus for S. Paolo fuori le mura43 and other churches, by the shafts in Thasian marble in S. Maria Maggiore, in the Porto warehouses and in the protyrum in SS. Giovanni e Paolo (Fig. 11) and by the fact that, among other things, in the last two cases the initials are seals of ownership of important personages of the late antiquity.44

Churches from the late fourth century and the first decades of the fifth century such as S. Vitale, S. Clemente and the old S. Sisto – not built under papal patronage45 – as well as the private domus (see the examples in Ostia) had previously mainly adopted composite capitals with smooth leaves worked ex novo, in as much as it was more difficult for lay people to obtain spolia material. When also in the huge basilicas under imperial patronage one needed to use contemporary capitals they were preferably placed, as we have seen, in a secondary position, as is shown by the composite capitals with smooth leaves employed in the lateral naves of S. Paolo fuori le mura.46 Also in one of the last churches where specially sculpted composite capitals with smooth leaves are used, that is S. Stefano along the Via Latina from 553, they are placed together with capitals from spolia, because of the impossibility of obtaining them in greater quantity.

In the fifth century we also observe a haphazard abandonment of the Imperial Forums: Some, such as the Trajan’s Forum, are still preserved and were probably subject to maintenance, as is already shown by Constantius II’s admiration when he visited it in 356 and as the archaeological evidence for quite prolonged use demonstrates. Others were abandoned, such as Caesar’s Forum, from which a number of marble elements were removed for the new Lateran Baptistery built between 432 and 440 by Sixtus III. Among them were the famous bases with acanthus, the object of continuous graphic reproductions from the Renaissance onwards,47 as well as several Corinthian capitals of the Asian style, which were probably part of some annexe of the forum, as fragments matching the capitals and the bases have been found there.48

We also have the problem of the titulial ready set in domus or their annexes, like the baths. In their architectural transformation into churches with naves they would probably have used the columns of the same building in which they stood, as seems be the case in S. Pudenziana, where the columns and the capitals of the goblet type from the thermae annexed to the Pudentes’ domus were reused.

A more complex issue is reuse that took place in the late fourth and in the first half of the fifth century in the new ‘forums’ and in buildings constructed or restored for lay purposes and re-dedicated to the reigning emperors by the urban praefecti, because they used elements from the buildings that were themselves under reconstruction, or partially from other adjacent and abandoned ones, or once again taken from warehouses. On this account we should like to mention, for its peculiarity, the compound that occupied the area in part underneath S. Maria in Cosmedin (Fig. 12) the foundation of which in blocks of tufa (21.70 x 31.50 m)49 has been found under the apses of the church and which has been tentatively identified as the basis of the Ara Maxima.50 Part of this compound still consists of the remains of an adjacent colonnaded hall of which 10 columns supporting the arches are visible, as they were incorporated in the west wall (seven shafts)and in the north wall (three shafts) of the church. It is possible to identify them as spolia because the remaining shafts – cabled and in white marble, but, according to a description from 1715 of the church, also smooth on the east side of the hall, which no longer survives51– are of a slightly different height, at around seven meters: consequently the height of the capitals and bases differs, being shorter on the north side where the three columns are taller. This fact together with the six arches in reused bipedal bricks, ca. 2 meters high, preserved along the long side, has led to dating it to the late empire, an age to which also belongs the raising of the level of the square to the same level as the strip along the river bank (already raised by 1.77 m in the second century): to this time can be dated the dedication, found locally, of a statue of Constantine by Creperius Madalianus, praefectus Annonae in 337-341. We can therefore include the works in the Ara Maxima Herculis among the restoration works that were carried out in the squares between the fourth and mid-fifth century by the prefects of the city, who often commemorate their deeds such as the building of brand new forums.52 As regards the reused columns, then,we could think of a provenance from that very area, perhaps from a portico or a propylaeum (see the use of the composite order that in Rome was never used in temples),which would confirm demolition and damage in the cult area dedicated to Hercules in the Forum Boarium.

The fact that porticoes and propylaea with different functions were continually built in the fifth century is demonstrated by the portico which closes to the north the Area Sacra of Largo Argentina and which runs parallel to the east extremity of the Hecatonstylum.53 We believe that here columns and bases were employed from the com-pound of Pompey’s theater, whose annexes, therefore, had already begun to be dismantled at this time.54

Sixth to Eighth Centuries

The Byzantine re-conquest of Rome did not bring major restoration works, despite the expression in the Pragmatica Sanctio of a wish to see to the maintenance of the public buildings, of the Forum and the Tiber river bed in Rome and of Porto (consuetudines etiam privilegia Romanae civitatis vel publicarum fabricarum reparationi vel alveo Tiberino vel foro aut portui Romano sive reparationi formarum concessa servari praecipimus, ita videlicet ut ex isdem tantummodo titulis ex quibus delegata fuerunt praestentur), but these few words indicate that the evidence for these works should be sought in epigraphic and archaeological sources. It is probable that the expression purgato fluminis alveo in the inscriptions (copied out by the Anonymus Einsiedlensis: CIL, VI, 1199 a–b; ILS 832; PLRE III Narses I) on the Pons Salarius on the river Aniene, rebuilt by Narses in 565, refer to the directions of the Pragmatica Sanctio, but it is important to underline that the bridge parapets used the same plutei (known by means of the engravings by Seroux d’Agincourt) as the Byzantine imports in Proconnesian marble in S. Clemente.55 This would therefore confirm that the great personages connected to the court in Constantinople were still intervening and still able to use imported, and not just reused, marbles. A further observation is that the inscription just quoted is the last to give us information about the renovation in Rome of a public monument by the imperial power – ex praeposito sacri palatii ac patricius et exarchus Italiae – the same formula used in the last attestation of a direct dedication by an emperor, on the Column of Phocas in the Forum Romanum in 608, though previously erected in the fourth century (Fig. 3).

Apart from the construction of churches with women’s galleries (S. Agnese fuorile mura) it is not possible to establish precisely the echo in Rome of Justinian’s great transformation of Haghia Sophia in Constantinople with its cupolas and women’s galleries, but the sources inform us that eight huge marble columns were removed from the Temple of the Sun and transported to Constantinople to be used in Hagia Sophia. The stripping of these columns would go on to play a fundamental role in the attitude towards antiquity on the part of the builders of new churches in Rome, the more so if we accept the symbolic meanings that some have wanted to see in this grandiose and ex-pensive reuse of shafts of porphyry from Rome in the capital of the Byzantine Empire.56

But in the sixth century the developments in Rome are in full contrast to what was happening in Constantinople. The Forum of Peace, which had remained in partial use despite various transformations in the fourth century when commercial structures were set in it (a horreum, a macellum?), had by now been abandoned and its temple definitely damaged, perhaps by a fire caused by lightning, as is recorded by Procopius,57 or because of a general decline of the forum complex analogous to that of the other Imperial Forums in antiquity. In any case when Constans II visited it he found the forum in good condition,58 which, moreover, had been rapidly restored after the earthquake of 408.59 It was only between 526 and 530, that the southern hall was occupied by the church of SS. Cosmas and Damian, and Procopius’ story about its state of abandonment can be set shortly afterwards. It is worth noticing that such a reoccupation made possible the preservation of part of its ancient walls in opera quadrata, which were still seen by Ligorio and were studied on the occasion of the restoration works in the 1950s.60

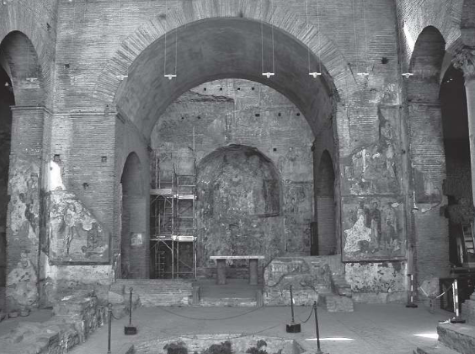

At the beginning of the seventh century the huge Pantheon in the Campus Martius was transformed into a church but what we are interested in emphasizing is that in the second half of the sixth century some of the huge, circus-like, cemeterial basilicas built around the city’s periphery must have been partially abandoned. We believe that from S.Agnese came many of the architectural elements reused in the smaller basilica of the late sixth / early seventh century, which was built in the immediate vicinity and connected to the local catacombs. The same hypothesis can be put forward for S. Lorenzo furorile mura, with all its entablature made of reused pieces (Fig. 13), as many of its cornices are from Constantine’s time and could have come from the circus-like basilica61 which stood nearby (Fig. 14). In fact the circus-like Basilica of S. Lorenzo was different from the others of the same type, as it had columns and not pillars with an interaxis of 3.15m.62 While Krautheimer thought that the ancient elements of that church had been reused in the later Honorian basilica,63 as he assumed that the circus-like type was abandoned during the ninth century, on account of the lack of information about it thereafter, it is the very reuse of Constantinian cornices and frieze / lintels in the Pelagian church that may indicate that abandonment could have begun in an earlier period.64

But there are not only Constantinian architectural elements: in S. Lorenzo columns and capitals can be dated to the second century AD or probably to the second quarter of that century, together with many of the pillars, while other elements which were reused as trabeations can be more generally attributed to the Antonine age (Fig. 13). The shafts with their appropriate capitals and bases seem to be organized according toa principle of total homogeneity, as they were probably removed from the same monument. Only the first couple of columns towards the presbytery appear slightly different, as they use figured Corinthian capitals (Fig. 13) and cabled columns instead of fluted columns and Corinthian capitals as everywhere else in the church. Also S. Lorenzo like S. Agnese features women’s galleries, whose material perfectly complies with the principles of symmetrical contraposition.65

We have cited these two churches as examples of a possible reuse of materials from nearby buildings because in the Byzantine age the reduction of the inhabited areas and also of the size of the churches had as consequence a noticeable change in the modes of the reused spolia, contrasting with the fourth to fifth century. From the sixth through most of the eighth century the reduction of the city, often imagined as a group of villages set on ancient, by now ruined, monuments, meant that the stripping of material for the new churches of that age mainly concerned the ancient monuments upon which they were erected, and to a lesser extent those farther away. The difficulties and the expense for transport would have not allowed supply from other parts of the city.

Increasingly, private dwellings were set into the old monuments: we may briefly cite the case of the Basilica Aemilia, where the fall of the perimeter wall had been caused by the collapse of the colonnades. Bartoli saw this as having been caused not by the fire of the early fifth century, which was restricted to the ceiling of the central hall and for which remains of ashes were found on the floor, but by the removal of the marbles of the internal space (the marble element appeared broken not because of a fall, but by mallet blows, and the column drums were all brought up to the same height).66 But in three tabernae of the basilica (towards the temple of Antoninus and Faustina) remains were found of floors from the eighth to ninth century and even later wall additions which bear witness to a Christian use, while, still in the tabernae area and all the way up to include the socle of the basilica, the remains of an early mediaeval house seem to have been discovered. It was a rather large one with walls made of big blocks of ‘greenish tufa’ and with a ‘primitive’ staircase leading to the upper floor: as the threshold of a room a marble block had been utilized containing part of the oldest consular fasti, originally in the nearby Regia.67

It should be noted that after the seventh century and still for many more centuries, the jurisdiction of the ancient monumental remains passed into the hands of the papacy, so the control and the relevant laws were weakened, since the popes themselves exploited the ruins as they deemed best.68 In fact a substantial change had taken place in the government as the Senate, who by now had only a ceremonial role, had in 603 been substituted by a board of persons chosen from among the main families of the Urbs with a merely consultative role. The offices of praefectus urbi and curator aquarum are attested until the beginning of the seventh century and the curator Palatii is still mentioned in 687. While on the one hand the papal curia’s formal obedience to the officials appointed by the Ravenna Exarch to govern the city continued, on the other hand a permanent ambassador was sent to Constantinople, not least to accelerate the endorsement of the new popes by the Emperor.

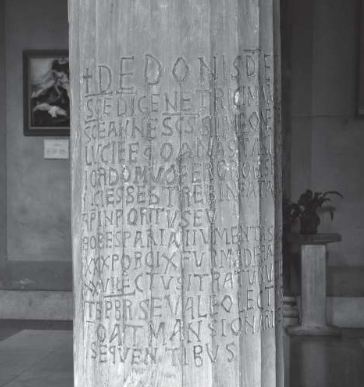

That a set of laws preventing the occupation of the ancient Roman buildings was not in force is rather proved by the fact that in the early middle ages an important moment of reuse and transformation in a Christian key can be registered in areas not yet occupied for that use, such as that near the ancient port on the Tiber. So S. Nicola in Carcere where the inscriptions of Anastasius Maiordomus engraved on a column (Fig. 15) attest that the church – at that time dedicated to SS. Maria, Simeone, Anna and Lucia – was built in the eighth century on top of the three temples of the Forum Holitorium: inside, it was possible to reuse elegant cannelured columns and very fine Corinthian capitals because Anastasius Maiordomus through his administrative position at the papal court was able to obtain well preserved spolia. This is also the case with S. Maria del Portico, which occupies the site of the Horrea Aemiliana and was built in the eighth to ninth century;69 S. Maria de Secundicerio, which is set in the Temple of Portunus; and again in the eighth century S. Angelo in Pescheria, which was built in the Porticus of Octavia (Fig. 4). But at the same time the Christian occupation of the ancient and most important monumental area of the city was carried out: the Forum. In fact in the sixth and seventh century the era of the huge transformation of the monuments in the Roman Forum began, which until the end of the fifth century had remained the privileged area of imperial restoration works and of the praefectus urbi. If still in 608 an honorary column had been rededicated by the emperor Phocas (Fig. 3), a few years afterwards, in 625-638, even the Senate House was transformed by pope Honorius I into a church, that of S. Adrian. In a period before the late eighth century the church of S. Martina had been built in the Secretarium Senatus and to the seventh century can be dated the diaconate of SS. Sergio e Bacco near the Arch of Septimius Severus. The diaconates – assistance centres for the needy modelled on governmental structures by now out of use – were run by lay officials of the Curia but were inspired by the principles of Christian charity, which explains the presence of the annexed oratory.

Still in the seventh century there was the adaptation of the vestibule of the imperial palaces on the Palatine for the church of S. Maria Antiqua (Fig. 16) and even more significant is the fact that later, in 705-707, Pope John VII set up a papal residence right beside this church itself. This is a first presage of what will happen with the iconoclastic crisis in 726, when the definitive separation from the Byzantine Church took place. The popes, then, started to create residences and administrative centres to face the needs of autonomy. John VII’s successors preferred to go back to the Lateran Palace, which was better suited for the necessary changes and exactly to those years must be dated the placing there of the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, identified as Constantine to the faithful (according to the new principle of the interpretatio in Christian key of many of the city’s antiquities). It is precisely the phenomenon of the adaptation into churches of the ancient buildings of the Forum that bears witness to the power obtained by the popes and the indifference or some such change of attitude and mentality of the Byzantine emperors towards the monument-symbols of the power of Rome. Therefore it was within this new political and economic situation that the ancient and prestigious buildings from the height of the imperial age were re-appropriated for new functions.

While on the one hand the practice of the removal of spolia from ancient buildings continued, on the other hand it is mainly in exceptional cases that it happened to monuments far away from the place of use, such as the defence works or the huge apostolic basilicas which are still the destination of pilgrimages and the object of restoration work. The roof of St. Peter’s was redone under the reign of Honorius I (625-638) with the bronze tiles from the Templum Romae (that is the Temple of Venus and Rome).70 After the fall of Jerusalem in 640Rome became the only holy city to be visited by Christian pilgrims and was therefore more than ever motivated to preserve its heritage. The emperor Constans II himself visited the city in 667 during his campaign against the Langobards, despite the fact that on that occasion he finished off the removal of the bronze still remaining on the Roman buildings, including that on the Pantheon. Less than a century later (731-741) St Peter’s Basilica received from the Exarch Eutychius the gift of six spiral columns with grape tendrils, imported from the East and placed by Gregory III in the presbytery in front of the ‘confessio’ in line with the six more ancient ones:71 it represents the last official concession of the Empire to the Church.

Ninth Century

In the ninth century, as is well known, favourable political conditions were created by the alliance against the Langobards between the French monarchy and the papacy – the latter having achieved complete control over the city –, leading to development, also in construction, in the city. A consequence is that in the ninth century a great change took place regarding both the occupation of the ancient monuments and their spoliation, in as much as there was a return to a process of systematic removal, which no longer concerned only the areas near the buildings to be constructed or restored but also more distant areas with ruins.

First of all, although under Leo IV (847-855) the first large edifice integrally built,rather than adapted, since the classical age, namely S. Maria Nova, which occupied part of the Temple of Venus and Rome (though so much of it remained standing that it was again stripped during the following centuries), was built in the Forum, by now the principal area of the city had become the bend of the Tiber close to the bridge that led to St. Peter’s, though at the same time other settlements still survived and a certain development in construction also started beyond the boundaries of the bend itself. In this century the occupation of the monumental buildings of the Campus Martius was completed, which offered the possibility to create liveable dwellings: these were the theaters (of Marcellus, of Pompey, of Balbus), Domitian’s stadium, Domitian’s odeion, whose corridors and vaulted rooms – the substructure of the cavea – became housing areas for the population, who referred to the places they lived in as ‘crypts’. It is certain that these buildings for public performances, earlier the subject of only partial stripping, were systematically plundered and despoiled of their marbles, which were to be used for church decoration (see later the case of S. Prassede with the spolia from the theater of Marcellus).

This process of occupation is naturally due to the pole of attraction of the nearby Vatican, immediately on the other side of the river: pilgrims coming from the north necessarily had to cross the Campus Martius on their way to St. Peter’s.

But the northern section of the Campus Martius became at this time the object of particular attention specifically regarding the removal of ancient marble, which we can define as systematic, to such an extent that we can describe it as one of the privileged fields for plundering. This conclusion is based on the observation that in the Carolingian churches of the whole of the ninth century, two large groups of architectural elements are employed as a support in the outside cornices of the apses. The first one consists of coffers decorated with masks with acanthus, the second of brackets lined with acanthus leaves. In both cases they were cut out from the cornices of the same monument of the imperial age with the aim of achieving a very high number of decorated elements suited to conform to the semi-circular perimeter of the apses. SS. Nereoe Achilleo (Fig. 17) and S. Martino ai Monti (Fig. 18), in particular, reuse brackets coupled with ceilings decorated with acanthus masks or vegetal motifs.

Probably the same is true of S. Prassede and SS. Quattro Coronati, because, though the cornices now consist only of brackets, they were originally completed by slabs decorated with large masks,as samples no longer in situ in the two churches confirms; S. Cecilia and S. Giorgio in Velabro, on the contrary, seem to have been designed from the very beginning only with brackets. We have six churches, then, built over the fifty years from Pope Leo III’s reign to that of Leo IV which seem to have been designed as part of a shared project, beyond other architectural differences, and which seem to have used the same source of material.72 We have elsewhere noted how the comprehensive analysis of all these pieces led us to believe that they must have come from a precinct with a wall at the end, organized with niches set at different levels, which we have proposed to identify as the compound of Aurelian’s Temple of the Sun. This is the period that is matched by both the style and the type of the acanthus, and its distinctive precinct with an apse surrounding the temple permits the identification of different groups of brackets and masks of acanthus leaves on the basis of their size: they fit well into a hypothetical reconstruction of a precinct with walls organized in several superimposed orders.

But the importance of the reuse employed for these churches is that for the first time we see spolia re-worked in a careful and systematic way in order to give greater uniformity and coherence to their positioning.

With the Carolingian age another phenomenon emerges that concerns churches especially: the reuse of architectural elements and other material from earlier phases of the churches themselves.

This is what seems to be implied by the fact that churches such as SS. Quattro Cornati and later S. Saba and S. Giovanni a Porta Latina, show homogeneous sets of Ionian capitals of the late fourth to the first decades of the fifth century73 (Fig. 19), mostly the results of finishing off, in late antiquity, of pieces imported in a semi-worked state from the Thasian and Proconnesian quarries but also obtained from the re-working of reused blocks in Luni marble (see above). This aspect is particularly significant, as it will influence the rebirth of the Ionian order in the Cosmatesque workshops in the eleventh and the twelfth centuries.

Capitals like these were set in place at SS. Quattro Coronati in the ninth century phase when the church reached its maximum size thanks to Leo IV (847-855), who had previously been its presbyter, and to that phase perhaps can be dated the reuse of several architectural elements, also of a Doric entablature that was moved from the Parthian Arch in the Roman Forum.74 They are now visible in the court in front of the church of the eleventh century (Fig. 20), reduced in size because of the damage caused by the Norman plundering of 1086.

It is a fragment of a ceiling cornice of the Doric order, which corresponds to a similar piece displayed in the cloister (Fig. 21).75

But in the S. Barbara Chapel of the same basilica four jutting trabeations were used, set diagonally at the four corners,76 and which had been supported by four columns of verde antico marble, if it is they that are the subject of a report of the transportation of four columns in this material to the Vatican from the Basilica of SS. Quattro Coronati.77 Out of these trabeations three, plus the cornice of the fourth, can be attributed to the late fourth or early decades of the fifth century, on the basis of the form of the indented acanthus which had become fashionable in Constantinople at that time (Fig. 22), and where there is an important parallel in the propylaea of the Theodosian Hagia Sophia, opened in 415, whilst the fourth trabeation dates from the ninth century.78 A date similar to that of the Ionian capitals (Fig. 19) would then emerge, and it is impossible not to view this in relation to data that permit us to reconstruct the existence of a more ancient stage of the church, which certainly already existed in the sixth century (see the participation of the presbyter of the basilica, Fortunatus, in the 595 Synod) and is perhaps to be identified with the titulus Aemilianae,79 present in the list of tituli that took part in the 499 Synod.

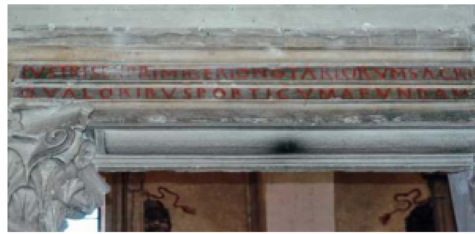

A peculiar situation is offered by S. Prassede: recent cleaning has brought to light the inscriptions, which had already been seen in the fifteenth century, on the trabeation supported by the columns in the naves, which refer to important offices of the fifth century (Fig. 23). There are 28 elements of trabeations, both smooth and decorated, including also those placed in the passage from the nave to the original transept. In the left side-nave, between the sixth and the fourth pillar there is a smooth trabeation (max. height 0.50 m, width 2.37 m, thickness 0.50 m) on whose first band VRBI CVRANTIBV[…] can be read and which can be related to a praefectus urbi, who underwent the damnatio memoriae, in as much as VRBI appears to be cancelled;80 between the third pillar and the fifth column, on the first and the second band of the architrave (max. height 0.50 m, width. 2.30 m, thickness 0.50 m) appears […]LVSTRIS EX PRIMICERIO NOTARIORVM SACRI P[…] /[…]QVALORIBVS PORTICVM A FVNDAMEN[…]. This is an inscription already partially known, as it is reported in a mediaeval manuscript (CIL VI, 1790) which falsely placed it in the S. Zenone chapel; a date between the fourth and, perhaps better, the beginning of the fifth century is demonstrated by the citation of the office of the primicerius notariorum sacri palatii, the head of the Guild of Notaries and the official responsible for the imperial archives, an office known from the fourth century onwards at the imperial court.81 In the passage from the right side nave to the transept – today the Chapel of the Cross – between the central columns and the pillar on the right, on the first band of the trabeation (width 2.0 m, thickness, 0.50 m) we have […]IVS FELIX AVG REFECERVN[…], with the possible restoration of [P]IVS FELIX, which would refer to a building reconstructed by Septimius Severus and Caracalla for whom the imperial title is pertinent. Evidently the first monument for which the lintels were sculpted was the work of the Severan emperors. This was restored and rededicated in a late period, when perhaps it became the seat of the primicerius notariorum. S. Prassede was possibly built within this monument, or rather, it was from there that the lintels were removed to be put in place in S. Prassede, which, we recall, has existed at least since the end of the fifth century when a titulus with this name was mentioned (ICUR, VII, 19991).

These lintels, inscribed again between the fourth and the fifth centuries, can be put in relation with a Constantinopolitan Corinthian capital with denticular acanthus that can be dated to between the late fourth and the first decades of the fifth century (Fig. 24), also used in the same church, which was wholly reconstructed as is well attested by Pascal I (817-824),82 who may very well have also used the marble remains of the previous phase.

Finally we can note that the eight columns with acanthus (Fig. 25) that currently decorate the sixteenth-century apse of S. Prassede, but which must have been part of the Carolingian phase of the church,83 are matched by an acanthus base from the Augustan age found in the theater of Marcellus, which underwent, besides a Severan phase, later

restoration works.

In order to better understand the changes in the relationship between Carolingian Rome and its ruins, a period characterized, as we have said, by a strong urban and construction revival, we have to point out the noticeable increase in the reuse of ancient blocks of tufa of large size that took place in the second half of the eighth and mainly in the ninth century. Because of their minor weight and ease of transport they were preferred to the heavier blocks of travertine and marble when they had to be used in structural elements reinforcing the masonry, in the levelling of foundation planes and in terracing. They were used without any other modification of the original form of the block in an irregular and poorly executed opus quadratum within which appears a number of interstices filled in with brick wedges, which, when used in the foundations, often stick out from the wall plane.84 Only when they are used in the elevation are the blocks placed with more precision, but in these cases they do not necessarily entail coherence in the wall masonry as they are often joined in the eighth century by walls in which bricks and small tufa pieces are mixed, in the ninth century mostly by bricks but in both cases always from reuse and with irregularities in structure. The rather strong increase in the reuse of blocks, tufa blocks and bricks in this period is proof of the increase in population and of the building revivals that characterize Rome in the eighth and ninth century, as the recent excavation in the forum areas has demonstrated. They have turned up porticoed houses from the ninth century in the Forum of Nerva, for instance, built with peperino blocks and masonry wedges removed from the monuments of that area.85 Here we give a list of the churches where the blocks were reused, because many of them featured the reuse of the ‘acanthus masks’, which we have already discussed above.

First of all must be cited the foundation walls in blocks, in the churches promoted or restored by Leo III (795-816) such as S. Nereo e Achilleo, S. Stefano degli Abissini, S. Susanna and S. Anastasia, where under this Pope the arches of the right nave were filled in with big blocks. The Liber Pontificalis attributes to this Pope also the building of S. Pellegrino in Naumachia whose foundations were made with big travertine blocks probably removed from Domitian’s stadium.86 We can also cite S. Martino ai Monti whose foundation is most visible along its north side. This church would fit into the category of the churches which exploited nearby monuments as a collection site for spolia, if it is true, as has been proposed, that the homogeneous set of Asian Corinthian capitals and very rare black marble bases in the columns between the naves come from Trajan’s baths. Such a reuse of blocks would indicate how the techniques of the building yards made important progress especially in these centuries, so that it made possible the systematic spoliation of huge Roman complexes built in opera quadrata, evidently by means of hoists, which also made it possible to build, for instance, a long wharf along the Tiber.87

All in all it is the eighth and mainly the ninth centuries which mark an inversion of the trend in comparison to the immediately preceding centuries, presenting extensive occupation of the city and no longer in a random fashion. The neighbourhoods tend to be spread widely and homogeneously and they reach beyond the limits of the Tiber bend in the Campus Martius next to the roads and bridges leading to St. Peter’s. Outside this area we notice the growth of houses in masonry with porticoes, as is shown by the domus recently discovered on the strata of mediaeval fill in Nerva’s forum, with porticoes in the front evidently built with blocks from the same forum. This announces the construction development that took place between the sixth and thirteenth century, which saw the city united in neighbourhoods without gaps.

Tenth Century

In the tenth century the city population mostly concentrated in those nuclei that had already merged in the previous century along the Tiber: the Campus Martius and, on the other bank, Pope Leo’s city and Trastevere. Trastevere had acquired importance because of the new establishment of river harbours: the Portus Maius on the bank of Pope Leo’s city and – perhaps from the mid-ninth century – the Ripa Romea harbour across the river from the ancient landing of the Marmorata. The unloading of wheat that took place there had required the building of several floating mills, which in turn attest population growth. But there is another area, the Aventine, which in the tenth century acquired a certain importance, according to the sources (Saint Odilo: prae caeteris illius urbis montibus aedes decoras habe[t]), and was chosen by the Roman aristocratic families as their residence. First of them all was that of Alberic, born on the Aventine (and who later had his home transformed into the Monastery of S. Maria, then S. Maria del Priorato) and who moved towards the SS. Apostoli, nearer to the city centre. It is right at the end of the tenth century (998-1001) that Otto III established his home on the Aventine near the Monastery of SS. Bonifacio e Alessio – a monastery of mixed Greek-Latin rite, which was destined to play an important role in the conversion of the Slavs.88 The tenth century was for Rome a distinctive period, at the beginning marked by a fierce fight for control over the elections of the pope between the Counts of Spoleto and groups of the Roman aristocracy, which for a long time determined the choice of the new pope. The anti-Arab league of 915, which defeated the Arabic settlement at the mouth of the Garigliano, saw the active participation of the gloriosissimus dux Theophylact and of the senator Romanorum Giovanni who backed Pope John X (914-918) in the decision to intervene. Theophylact’s son in law, Aberic, for over twenty years (932-954) controlled the Roman scene, obtaining the title of princeps and senator and living in a sort of palatium in imitation of those of the Langobard dukes in the south. His son became pope with the name of John XII. The Roman aristocracy increased their interests also in many areas of Latium, making alliances, tying relationships with the local powers and with Farfa and Subiaco, both large monasteries in Latium, and drawing them all into the Roman orbit.89

In the second half of the century the imperial authority was restored with the imperial coronation of Otto I, king of Saxony, by John XII: although the German emperors managed to determine the election of a few popes, the popes remained subject to the conditions created by the aristocratic group. In the last twenty years of the tenth century, the Crescentii took a position similar to that of Alberic (some of them received the title of patricius Romanorum) and the Counts of Tuscolum succeeded in crowning three popes between and. Otto I of Saxony came down to Italy – in order to be crowned emperor in Rome and to insist on the dependence of the papacy upon temporal authority (according to the privilegium Othonis the popes had to solemnly swear fealty to the emperor). He arrived surrounded by the fame of his victorious ventures in Eastern Europe and of his civilizing and missionary activity among the Slavs, which had its apex in the foundation of the new bishopric at Magdeburg. The cathedral he wanted to have built boasted columns, which had been especially ordered from Rome in imitation of what Charlemagne had done in Aachen.90 It has been generally noted that in the Ottonian age there was a strong attention and respect for the classical world, which has been interpreted as a cultural renewal, mostly with a literary connotation, together with a special drive to reform religious institutions with the support of the monastic centre of Cluny. Otto III (–), the most passionate in the attempt to promote some kind of renovatio of the antique in his choice of Rome as the actual capital city of the empire, was unable to leave a significant mark there in its buildings, despite his being inspired by Constantine and Charlemagne as his models and his collaboration with Gerbert d’Aurillac, the future Pope Silvester (–). In any case the tenth century is the date of the foundation of the church of S. Bartolomeo in Rome, known by this name only after. It is certainly to be connected to Otto III before, who was buried here, but the dedicatee of the church was initially St. Adalbert, Otto’s cousin, martyred in; the existence of a previous church seems to be excluded.91 The four columns, in granite of the forum, probably belong to the original building reused as a frame for the niches in the centre of the two pillars of the baroque façade, which replaced the previous narthex.92 The church of S. Sebastiano is to be attributed to the practice of constructing oratories. It was also known by the name of S. Maria in Pallara, which stood at the north-eastern corner of the Palatine, built upon the will of a physician Petrus, and was covered with wall paintings around the end of the tenth century, representing the martyrdom cycle of Saints Sebastian and Zoticus.93 The most ancient piece of information regarding the church is a mutilated epitaph dating to the tenth century with the praises of a person of noble origin, Marcus, who retired to live in the annexed monastery.94

The Church was restructured after the Carolingian Renaissance when in Rome a few small oratories, with an apse and only one nave, were built, many of which were for private use, while others, as in the case of S. Sebastiano, were entrusted to a community of monks.

The practice of using Roman spolia continues, done by both the emperor and the pope to bestow prestige and confirm a political role: it suffices to think of the reinterment, at Otto III’s command, of Charlemagne’s body in Aachen, buried in a sarcophagus perhaps brought from Rome, depicting the rape of Proserpina, which shows the importance of the representation of myths, which were redeemed as allegorical images that overcame the original significance. Otto II had been buried in in St. Peter’s atrium under a lid of porphyry taken from Hadrian’s mausoleum, whilst Otto III was buried in the cathedral in Aachen in a basin in red marble (ancient red? porphyry?), likewise lifted from Rome.95 The phenomenon of reuse was beginning to become international, as the need for prestigious marbles drove the search more and more towards distant sites and not only near the areas with ruins. No wonder that in the Byzantine empire, too, there is evidence of ships sent to collect marble ornaments for reuse, as is shown by the wreck at Kizilburun near Çesme in Turkey, dated to the tenth century on the basis of the amphorae carried and whose load contained also marble spolia such as columns, screens, a capital and window jambs taken from a church.96

The difficult political situation in Rome as well as in Italy did not allow construction of buildings of a large size such as basilicas or bishops’ seats by the imperial or ecclesiastical powers. Yet in Rome building activity on private initiative is recorded, even if not of a large scale, such as the construction of the small oratory of S. Barbara dei Librai in one of the arches of Pompey’s theater, or of the little church of S. Maria in Pallara in 998 –as we said, commissioned by the medicus Petrus (the present S. Sebastianello alla Polveriera), with frescoes characterized by decorative motifs inspired by the antique97 (see above). Or the transformation into the church of S. Urbano alla Caffarella of a small funerary temple in masonry from the imperial age, where the paintings are integrated with the previous stucco decoration, again commissioned by a medicus. These patrons bear witness to the existence of a social class separate from the local nobility who will acquire a more and more important role throughout the course of the Middle Ages.98