Exploring the doctrinal positions of the Church in the context of the Western intellectual disputes around the year 1000.

By Dr. Gabriela Tănăsescu

Researcher and Instructor in Political and Social Philosophy

Institute of Political Sciences and International Relations (Romania)

Introduction

This paper aims to situate St. Gerard of Cenad’s position in apocalyptic millenarianism as differentia specifica in genus proximum of the doctrinal position of the Church, subscribing to the thesis that Gerard’s position constituted an attempt to connect the Jewish apocalyptic literature and the Christian millennarialism. It argues that St. Gerard of Cenad used the hymnal poetry of the prophet Daniel not only in order to invocate as theological argument “the inter-Testamentary unit” ‒the fact that, in hermeneutic terms,the Old Testament announces the New Testament or“the coming of Jesus”‒,but also to criticize the arbitrary and unbelieving power and to transmit to it and to all those who “rise”against the faith, alike Nebuchadnezzar in olden times,an apocalyptic admonishment.

Research Purpose on ‘Deliberatio’

The assumption of the paper is that the critical,polemical, and apologetic writing of Saint Gerard, Deliberatio supra hymnum trium puerorum, illustrates in a specific, original manner the doctrinal position of the Church in the context of the Western intellectual disputes around the year 1000 and also in the context of local heresiarchs and ideological opponents to the Christian faith. The specificity of the Gerardian demarche is identified in the fundamental theological arguments formulated in his“philosophical treatise” where in the philosophy is understood dichotomously: in the desirable condition of the interdependence with the theology ‒ the sacred philosophy or the wisdom,[1] “the complete philosophy accomplished with the light of the Spirit,”[2] ‒ or in the undesirable condition of the delimitation from theology.

The paper aims to situate St. Gerard of Cenad’s position in the context of the year 1000 –“the great year of the West”[3] ‒ significantly marked by the restlessness, fear and terror of the “end of men” and the “twilight of the world,”but equally by hope and religious effervescence. It situates St. Gerard’s treatise in the context of the doctrinal positions of Church and magistri of time, but also in that of the attempts to connect the Jewish apocalyptic literature to the Christian millenarianism. It shows that,by choosing a hymnal poetry of Daniel – “a minor apoctif” from an apocalyptic writing – as a source of its impressive apologetic approach from Deliberatio supra hymnum trium puerorum, St. Gerard of Cenad intended, on the one hand, to invocate an inter-Testamentary framework[4] or “a common teaching”which, in a hermeneutical perspective, highlights that the Old Testament announces the New Testament, namely “the coming of Jesus, creator of all things,”[5] as a convincing theological argument to the heretics, Jews or to the Christians formally converted, more specifically to the king Sámuel Aba, as well as to those who had prevented “the search for truth”[6] and the fame of God’s Son, and thus the recognition of the superiority of Christianity.

On the other hand, the frame created by choosing the hymnal poem from Daniel, one without dogmatic significance, is understood as being appropriate for a harsh criticism of the categories involved in the disputes of the time: the contesting of the divine nature of Jesus, the dechristianization of “our people” “who see”, who “guided by me towards the happy Light”[7] or enlightened by faith, “abandon Jesus” and the“God’s law,” the attaching to the worldly things and not to the Light of Spirit,the violence, the arbitrariness and despotic monarchical power etc.

Finally, the Gerardian option for a Jewish apocalyptic writing as a pretext of his apologetic and hermeneutical approach is presented as having meant to be symbolically –for the recipients who refuse the eternal sapientia of the Christian faith, as Nebuchadnezzar refused in the olden times the three youths’ faith in God –an imminent, totalizing, and apocalyptic caveat.

In what follows, I shall refer to the Gerardian connotation of philosophy and to the ideologies considered by Gerard of Cenad as rivals to the Church doctrine and to its truths of faith, to his particular perspective on the millenarianism and apocalypse, circumscribed to the official position of the Church, and to his criticism of the categories involved in the intellectual disputesand in the religious and moral failures of the time and space in which“has he shepherded.”[8]

Gerard’s Philosophical Contemporaneousness and the Mystical Sects

What makes Gerard’s work so precious is primarily the courage of his polemic spirit engaged in the dispute with the non-sacred philosophy and with the various heresies of the time, especially with the mystical ones.

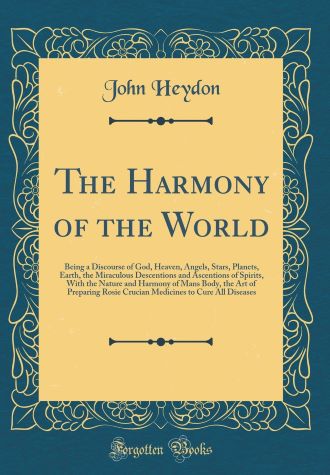

Gerard was an exponent of the post-Carolingian era, a time of revitalization of education and, with it, of philosophy, that culminated with thinkers such as Anselm ‒ “a major transitional figure”[9] towards a more technical, “academic,” “argumentative”construction,‒and Abelard ‒the most important and original philosopher,who claimed the ascendance of “reason over authority.”[10] The thinkers who preceded them, among them St. Gerard of Cenad[11] and some of his contemporaries‒which treated various philosophical themes in a still unsystematic manner, but in a “visionary” mode, having ample recourse to “the Neo-Platonist tradition”[12]‒ have legitimized the philosophy within the dominant model of the post-Carolingian era.As revealed by Ignác Batthyány,[13] the perspective from which Saint Gerard approached philosophy was that of the necessary interdependence between philosophy and theology of what Ian Scotus Eriugena aimed by the equilibrium or “the harmony” between the two. For the “enlightened rationalist”[14] of the Middle Ages, Ian Scotus Eriugena, philosophy, as “faith and reason”[15] which constitutes the only way of salvation, can never enter in conflict with the authority‒ the theology ‒ which is indeed legitimate. As such, “the true philosophy is the true religion, and vice versa, the true religion is the true philosophy.”[16]

Following this model, Gerard, essentially legitimized philosophy in the condition of disciplinarity, namely in a distinct condition but in “a meaning which does not exceed the boundaries of faith.”[17] Thus, the proper condition of philosophy or what he named“the true philosophy,” “honest explaining,” the true science,”and the “wisdom”[18] “the complete philosophy accomplished with the light of the Spirit,” is the philosophy which searches “the sacred principles of all things” and understands “the sapient mysteries,” namely the invisible part of the God which is part of human spirit or of human realm of ideas which keeps the human mind “in the highest admiration for the splendour of God.”[19] Contrariwise, the improper condition of philosophy is that of science of principia, the teaching of “mortal” or “visible” things, the non-sacred philosophy which rejects the mystery of occult things or the archetype of wisdom and which denies Jesus. Gerard’s conception of sacred philosophy or of the philosophy as search of divine wisdom is placed in a symbolic mode of world understanding, characteristic for the beginning of the eleventh century, which spread inside the neo-Platonic tradition and struck with the realistic and logical thought (logica vetus) of Aristotle.[20] The fact that it “struck” was considered an interruption of “the natural doxology by the parenthesis of heretic philosophy” and an interpretation of it “under the Aristotelian category of substance.”[21] For Gerard, since only God has the attribute of entire wisdom, and only He is wise according to his substance, not to accident, divine wisdom must be the main concern of philosophy.

Gerard considered that those who preach the wisdom should not be “overlooked” because“not being themselves perfected, as it is appropriate,”as well as those who “raise their voices in squares shouting in front of crowds,”those who “sing and urges all the parties of nature without any remorse” but do not “utter aright.”[22] Those unprepared to see with the eyes of mind “the high sayings and to reflect on them”are imperfect, unaccomplished, because they do not “begin by praising the Creator of all creatures.”[23] The unreadiness and the imperfection prevent “an honest discerning” of the high teachings and “the congruence (concordia) with the good teachers.”[24] As a result, that kind of philosophies are surpassed by “learned people with no literacy,”[25] but full of grace, truth,and revealed knowledge, Peter thus being “deeper”than Aristotle, Paul a better orator than other rhetoricians, John “higher in his words than the sky”[26] and Jacob more skilled than Plotinus. The philosophers of elementa thus bend in front of “the fisherman’s philosophy” since “the primordial essence cannot be seen with the eyes…”[27] The explanation lies, as in the case of the three youths from the Song added to Daniel, in the“strength of virtue”[28] with which they brought together, in a single utterance, all visible and invisible things, into glorification.

Gerard, like other contemporary Christian thinkers, expressed from this point of view the confidence in the possibility of intuitive understanding and speculative knowledge of the junction between the visible and the invisible world, at the crossroads of space and time,at the encounter between cosmos, microcosm, nature, morality, and faith.This spiritual attitude, amply shared by scholars and theologians around the year 1000,has underlined the belief in the existence of an essential cohesion and harmony between that part of the universe which man can understand through the senses and that part which eludes the senses. The knowledge of the permanent, intimate and infinite correspondence between nature and the supernatural as divine is the one which opens the way of the mystical illumination and which fortifies and completes the faith and the moral condition of the human being. In a similar manner to that which the three youths[29] have remained unmoved in their faith in God and in His miracles, they have been rescued by angels and have exalted to God the glorification and fervent blessing. The three young men had the moral strength to oppose the King who desired to change their faith, have refused to please the King,“a mortal man, who is today, and tomorrow will no longer find any trace of his on the face of earth.”[30] Thus,for Gerard,the condition of perfection included“the open mind” towards “the true meaning”, towards “faith and love”[31] and, equally, towards moral strength and firmness. The philosophy which has not fallen into this condition remains useless, bypasses wisdom and remains the teaching of the perishing, mortal things. Instead, the philosophy situated in the condition of wisdom seeks the Truth.

The philosophy fallen in the condition of wisdom or “the treasure of wisdom”[32] is that which leads to faith, the one not reached by the famous rulers of antiquity who acquired and divided the world, neither the Stoics, nor the Platonists, the peripateticians, epicureans, or gymnosophists. Gerard radically combats the claim of some philosophers like Marcobius, Zenon, Menandros to investigate “the secret things” “in the darkness,”[33] as well as the noxiousness of the heretics and sectarians. Also,Gerard combats the Manichaeism with Balkan origin (of the preachers who came from across the Danube in the years 1014-1018), that with oriental origin specific to the Turanian Pechenegs, the Cathar heresy and the Asian superstitions, probably Karaite (Khazar),brought by Pechenegs or even by Hungarians, along with the views of certain obscure heretics which are mentioned in the writings of some Hebrew theologians. In the list of heresies inspired by Isidore of Sevilleʼs work, Etymologiae, Gerard includes the Jewish sects which were contemporary to the emergence of Christianity (Simonians, Nicolaitans, Cerinthians, Ophites, Cainites, Melchisedecs), the early Christian groups derived in the first and second century from the rabbinical interpretations (Menandrians, Cerdonians, Marcionites, Archontics), the Hermogenians, Heraclitians, the communities which did not join the Episcopal Church organized in the third century (Novatians, Noetians), the Arab Judaizing trend of Ebionites, the agnostics and Cathars or Bogomils which were, for Gerard, the main ideological opponents.

Contrariwise, the opposite exemplifications of the wisdom which leads to faith, according to Gerard, who quotes here from Corinthians II, are Dionysius, Irenaeus, Ignatius, Polycarp, all situated “in a complete philosophy”[34] and, as the three young men from the hymnal poem added to the prophetic book of Daniel, “perfected with the light of Spirit.”[35]

Millennial and Emotional Contemporaneity and the “Harmony of the World”

The Bishop of Cenad was contemporary to the millennium turn, the fundamental date of “the world story,” “the great year of the West”[36] or the millennial year of fears and belief in the end of the world.

The idea of the end times in the year 1000 and the fears generated by it are located in the Christian millennialism ‒ in the belief that Christ should rule the world for a thousand years‒, following an ancient Judaic tradition.[37] For the early Christianity,this belief involved the supreme struggle against the enemies of the Lord, Christ’s return, the Doomsday, and the foundation of a glorious kingdom on earth.

As commentators highlighted within recurrently enriched interpretations,[38] the Jewish apocalyptic literature is not entirely a millenarian one, since in the Old Testament, in the Psalms, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, the Messianic kingdom is endless as duration. As the distinction between the coming of the Messiah and the revelation of the divine Judge was introduced,the Messianic Kingdom begins to be limited in duration. Thus, Baruch limited the Messianic Kingdom but he only specified that it would last until to the end of the world corruption, thereby introducing the distinction between the Messianic kingdom, in which the world is still struggling against sin, and the kingdom of Glory. In the Apocalypse of Ezra and in the Talmud, the Messianic kingdom lasts for 400 years, but also the Jews preponderantly attributed one millennium to the Messianic kingdom, a day of the Lord, a day of a thousand years. In the Middle Ages, however, the vision of the great week reappeared, i.e.the seven days which represent the seven ages of the world, the last of which, Messiah’s kingdom,being the Sabbath. However, as Focillon pointed out following Harnakʼs thesis,neither the evangelical literature (scriptural) nor the apostolic one (dedicated to the manner in which Christ and the authors of the New Testament used the Old Testament) did not confine the duration of Messiah’s kingdom, with the exception of St. John’s Book of Revelation (The Apocalypse), which is, according to Henri Focillon, “a strange testimony of the survival of Judaic conception to the Asian Christians.”[39]

According to St. John’s Apocalypse, after a thousand years, Satan would appear for a short time but would be destroyed, the dead would rise from their graves and would be judged, and a new universe would be conceived, a kingdom of Glory. The idea of millenarianism becomes an essential element of Christianity, accompanied by a sense of hope, of an “awake” or“pending” consciousness[40] guided by the belief that, as the Lord had come the first time, He would return and would build a renewed world.

Thus, there is a striking contradiction between the evangelical humanism,that brings peace,and the apocalyptic Judaism ‒ Baruch argued that the earthly reign is not the reign of virtue and peace, but “the unfolding of fall and redemption drama, a drama full of disasters and collapses”[41]‒and the apocalyptic Judaism harbinger of fear. From the perspective of the soul, however, this contradiction proves to be the cause of a complementarity. In Western religious thought after the year 1000, the Apocalypse and the commentaries on it were no longer strictly linked to millenarianism, but the year 1000 has had a huge symbolic value.

From the perspective of historical interpretations, the meaning of anno Domini and anno Passionis 1000 reunited the apocalyptic (“revelatory”) belief in the “final moment when God’s ways are revealed as imminent”[42] and Christ’s return (Parousia), as well as the millennial belief or the eschatological expectation anticipated at the turn of a millennium (set in motion by the ecclesiastical teaching of the sabbatical millennium). In its chiliastic versions, these expectations referred to an end which would bring about a thousand years period of peace, harmony, and joy on earth for those who are favoured on the Judgment Day.[43] It should be mentioned that in the modern historiography the most prominent interpretation paradigms of the year 1000 are that of the “eschatological fervour” ‒ “arousing hope in the oppressed and terror in the oppressors”[44] ‒ created by the Romantic historians of the mid-nineteenth century,[45] and that of “anti-terrors school” or radical revisionist position, created by the positivist historians of the late nineteenth century,[46] who dismissed the apocalyptic expectations mainly because of “the utter absence”[47] of documentation attesting them and since the little evidence that survived is not directly related to 1000, but to dates such as 968, 1010 and 1033.

In fact, the ample emotional waves caused by the apocalyptic expectations concerning the year 1000, the feeling that the entire Christianity will step as one body the threshold of the year 1000,the unclear, but gloomy, perspective of a great “spectacle of death”[48] and depression have covered about half a century, namely the period between 980 and 1040 and especially the interval 1000-1033 circumscribed by the two“millennial anniversaries” ‒ the Birth and the Passion and Resurrection of Christ. Landes has shown that the apocalyptic year 1000, as all great “dates,” affected the period before and after and that “two generation stepped in an apocalyptic Zeitgeist.”[49]

To the observations which concerned the evidence and the documentation, the historians who have re-launched the critical study of the history of “obscure millennium”[50] replied by searching the cultural behaviour according to the social differences and the specificity of the phenomena of collective psychology. Essentially, their studies have been circumscribed by the reiteration of the fact that the Christian leaders of the Roman Empire and “the institutional superstructure” of Christianity have emphasized “the ill effects of a too passionate and too immediate sense of the end” and that the most prominent figures of the Christianity, such as Jerome and Augustine, have dismissed most forms of apocalyptic expectations and chiliastic hopes by pointing to the absence of any valid text that might hold out them.[51] The Augustinian tradition ‒ “Augustine’s radical agnosticism”[52], which culminated with Abbon of Fleuryʼs position, maintained that one cannot know the end and that the Texts are not to be taken literally. Furthermore, as the anti-apocalyptic voices of the“sober” clerical elites[53] rarely appeared in the texts, a “consensus of silence”was set up,and “the chiliasm disappeared from the West from Augustine’s day (early fifth century) until Joachim of Fiore’s (late twelfth).”[54] But this ample impact was primarily on scribal production and not on Christianity as a whole.Thus, medieval writers, who were churchmen, bishops,and monks, and who thus reflected “a closed mentality,”[55] avoided the subject of the millennium or used euphemisms, maintained that men must not interpret current events in terms of an apocalyptic scenario, and must interpret 1000 as an allegorical number symbolizing perfection, not as a fixed number of years before the Parousia. They were interested ‒ in the miser universe and in the highly hierarchical medieval society ‒ only in exceptional cases, in strangeness, in what broke the wells et order of things ‒ “signs and wonders,”warnings that God sent to his creatures miracles, predictions,[56] prophecies, disasters: earthquakes, comets, lightnings, eclipses of the sun and moon, famines, plagues, invasions of the Danes, beached whales, monstrous births, widespread outbreaks of sacerignis.[57] The meaning of this “web of wonders,” “correspondences” and “cosmic”cohesion[58] could not avoid the apocalyptic sentiment at the approach of the millennium.

For the political elite,the clergy and the usually passive mass of the population, the annals, chronicles, and historical works, reveal ,the pending of Parusia, the increasing of purification acts, individual and collective rituals of penitence, royal donations,[59] oath of fasting, penitential practices, prohibitions and renunciations, gathering of people to which numerous reliquaries and holy relics were brought. These gatherings meant to revive peace and establish the holy faith, to suspend hostilities during the most sacred periods of liturgical calendar ‒ the armistice of God, proposed to knights as a form of asceticism suited for their rank, pilgrimages understood as a preparation for death and as a promise of salvation. These privations were considered “the means by which the people of God could persuade divine vengeance, clear currently the scourges and prepare itself for the day of wrath”[60] and the core of the collective consciousness which was under the empire of a disturbing expectation. At the same time, they also expressed the intensification of the religious experience, the propensity for the spiritual and personal dimension of eschatology, and “the way in which the Last Things are realized for each believer in his or her inner experience of Judgment and the Kingdom of Heaven.”[61]

According to the Church doctrine, only God can decide on the end of the world, thus priests discouraged speculation, and pleaded “for exhorting the faithful to prepare themselves individually for Judgment here and now, regardless of the future of mankind.”[62] Notwithstanding,“the diffuse feeling ofʽthe twilight of worldʼ and the sadness of discouraged spirit attending the progressive decay of civilization… after the German”[63] and Turanik invasions were not purely intellectual but in agreement with a religious belief which went, in the middle of the tenth century, though an intense crisis, a doctrinal resurgence manifested not only in the chancellery, but also in the Church and in the public consciousness. The official position of the Church, imposed more strongly at the end of the tenth century through the voice of Abbon of Fleury (Liber apologeticus), is not to date the Judgment and not to force the mystery of divine providence. It is interesting to notice that Abbon de Fleury declared that he opposed the belief in the coming of Antichrist at the end of the thousand years with the help of the Gospels, the Book of Revelation and Daniel, and this declaration put him closer to Gerard. The fear of the end of the world and the fright of the disappearance of the human race exacerbated in the second half of the tenth century, but tempered even in the year 1000 as a consequence of the “prudent position of the Church”[64] and renewed in the entire course of the eleventh century, was so intense that it was interpreted as a new Spring of the world. According to a contemporary writer, “the chronicler of the year 1000,”“the greatest historian of this period,”“the best witness of his time,”[65] Raoul Glaber, “around three years after the year 1000,”the earth “shook off the dust of the ages and covered itself with a white mantle of churches.”[66] The prudent position of the Church, namely the canonical prudence in relation to the revealed text of Apocalypse, made as “the value of Apocalypse remain outside any possible challenge,”but, as Focillon had shown, to be “a somewhat un-temporal value, a sort of perpetual calendar of great spiritual anxieties, of a fear of the Last Judgment,”[67] a fear with a great moral potential.

According to Gerard of Cenad, the apocalypse does not mean a “pass” or destruction of heaven and earth, but the time of “a new heaven and a new earth” (Revelation), namely a change towards the better, towards a more beautiful state. The earth, as the Ecclesiastes show, which Gerard quoted, “will stand forever.”God will provide a world in which only its face will pass, but wherein the truth that removes the bondage of corruption will remain. The darkening of the sun and moon are not meant to end the world, because God would not allow the ending of the world, but they are meant to improve it. Undoubtedly, the Sun would eventually return to its normal state, but it will be stronger, lighted by an unseen Sun, a lamp, that of the Lamb,and this light will be of an incomprehensible clarity. So, as John showed, the first Heaven and the first earth will end, but there will be a new heaven and a new earth in which everything that was subjected to corruption has been removed. Thus,the corruption and degradation will pass, making room for the limpidity of faith and for God’s glory. The earth will be purified by fire, washed by water, and will become a clean earth on which nobody masters. The Apocalypse will therefore take place when the Lord will be pleased with the spiritually-renewed and purified Heaven and Earth. The condition of the world that is to come can be perceived only from that state of spiritual perfection and love that surpasses everything. Through perfection and love “the mystery of the greatest significance,”“the mysterious chant” of “the world harmony,”[68] can be researched – that harmony in which the sky and the earth, the sun and the stars sing to the Lord. The worship and singing for the Lord, as in the case of the three young people, is with the word, with the mouth, but especially with the deed. “The deed is that which sings”[69] and thus contributes to the largest extend to the preaching of God and of divine law.

Historical Contemporaneity and the Criticism of the King as Mortal

Gerard probably perceived in the most acute manner that the century’s end was manifested as a phenomenon which looked, Janus-like, both to the future and to the past.[70] The Venetian who became Bishop in Cenad, in the vicinity of a suzerain territory whose population was Christianized around the year 1000 by the Archbishop of Prague, St. Brunon, ‒ the White Hungary ‒ and by the Archbishop of Bohemia, St. Adalbert ‒ the Black Hungary or the descendants of the Magyar hordes, of the Kavars and the Kuns, had an important and difficult missionary task. It is worth noting in this respect that Rome and Byzantium, which “were competing for the souls of the east European peoples… were anxious to add the Hungarians to their bag.”[71]

The Christianity of the year 1000, before the great schism, was already divided between the Church of Rome ‒ with its weakened authority caused the lengthy scandals of the Popes of Tusculum, with complaints on dogmatic and liturgical issues, and with a deep and deaf contradiction caused by habits, states of spirit, traditions of different environments, and the Greek Church with its different approach, with its orthodoxy, with its distinct political role. In essence, it was a world of disunity, rebellions, intrigues, “a world of feudal beasts and simonies.”[72]

It should be added that this great Western anxiety of mind of millenarian origin was parallel, as Focillon showed, to “a great moment of the history,”[73] namely the construction of the Holy German-Roman Empire on the ruins of the Carolingian Empire (lasting until 1804) the end of the Capetian dynasty, the“great political constructions of the Normans,”[74] but also, especially in Central Europe, the return of Hungarians, who in the tenth century burned the monasteries from Gallia, against the peoples of the steppe, and established (in the year 1000) the apostolic monarchy, constituting themselves as “defenders of Christian Europe.”[75]

St. Brunon christened the Hungarian King Gönz (Géza) of the Árpád dynasty, called, and changed his name to Stephen. The Emperor Otto III received Stephen after the baptism, on the day of the martyr Stephen, and gave him absolute power over his kingdom and allowed him to wear the saintly lance everywhere. Stephen’s son, Vajk, was also baptized by St. Brunon as Stephen (István), with the condition to determine his people to convert to Christianity. He finalized a matrimonial alliance with the Bavarian House: Stephen married HenryIII’s sister, Gisella in 996. The Hungarian Kingdom was recognized by Rome in 1000 and the new kingdom was linked to the Holy See under the title of apostolic monarchy, while its king was known as “one of those rulers by the Grace of God whose legitimate rights his fellow-princes could not infringe without sin.”[76] Furthermore, Stephen was canonized in 1083 as Stephen I, together with his son, Emeric, and the Bishop Gerard of Cenad.

The Hungarians were Christianised under Saint Stephen’s order, thus the missionary activity “worked from top to bottom, introducing not the popular Christianity of Peace councils and pilgrimages, but that of monarchical and episcopal authority,” in contrast to the West, where the impact of apocalyptic beliefs “tended to work from the bottom up, triggering large demonstrations of collective piety.”[77] Consequently, the Hungarians “joined the ranks of the Christian kingdoms of Europe, together forming Christian Europe.”[78] Thus, the Danube River and the Banat Voivodeship became Rome’s natural frontier to the north and the frontier of Romanity lay far to the south of the Danube, what assured a remarkable stability of the Empire Eastern frontier.[79]

After Stephen’s death, in 1038, riots affected the Voievodeship of Banat, but at the time the Hungarians were already part of Christian Europe, of a “supra-nation” understood as being the very essence of Christianity, a spiritual agreement or an universal society, a community of different traditions, languages, seniorities,and status of civilization.[80] After Stephen, the Venetian Petro Orseolo (1038-1041)succeeded to the Hungarian throne.He was the son of Stephen’s sister, who ruled in an authoritarian policy which ended in a rebellion resulting in his replacement with Samuel Aba (1041-1044)-who was probably Stephen’s brother-in-law, the husband (or the son of the husband) of Gézaʼs daughter. Descending from a family headed by the Kabar tribes which seceded from the Khazar Khanate and which joined the Hungarians in the ninth century, Sámuel Aba executed many of his opponents and eventually came into conflict with St. Gerard of Cenad. The throne was reconquered by Petro Orseolo (1044-1046) with the help of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III, whose vassal he became. He was killed in the rebellion of Vata, which also martyred St. Gerard, a rebellion which sought the abolition of Christianity and the restoration of paganism in Hungary.

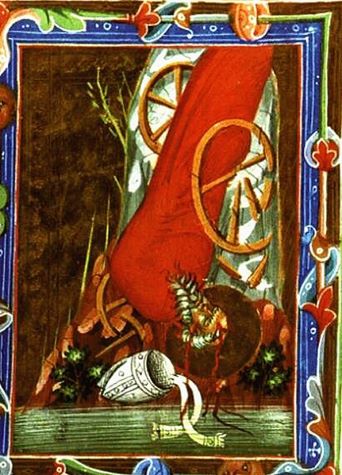

What it is meritorious,impressive,and particularly actual for our society is the manner in which Gerard of Cenad had the courage to question authority in general and the king in particular, the person who was the temporal leader and who was not to be an abusive layman or an opponent of the Church and faith,nor a heretic or a mystical interpreter of the Bible. Like the three young men who lamented the existence of the lawless people and the worst amongst ungodly ones, an unjust king,of the unwavering faith in God and in His miracles, and of the angel of the Lord who descended and touched with dew whiff the flame of furnace where Azaria and his friends were and worshiped and fervently blessed God, Gerard of Cenad bemoaned those who did not have the“strength of virtue,”[81] the priests who, yielding to pressure, detacht hemselves from Jesus and renounce the faith. He deplored those who didnot have the courage to affirm conscience and dignity, those who “just murmur,” who “did not dare to scold not to offend the prince’s ears,” those who “feigned lygrin so that they or their relatives not be removed from their services” or removed from offices.[82] The Bishop of Cenad bemoaned those who were afraid of people and of their habits, those who were afraid of offending any “mortal man” even if he was the King, “who exists today, and tomorrow one will find none of his trace the face of earth.”[83] In other words, Gerard of Cenad rejected the voluntary, cowardly,and irresponsible submission to the “injustice which masters the world,”to the greed, looting,and persecutions led by those placed at the top of the power, to everything which infringed the divine law, including the philosophers who served masters, who were attached to the treasures of this world and not “to the unspeakable treasure”[84] of the heavenly kingdom,and who did not react against the violence, tyranny, arbitrariness,and despotism of the monarchical power. From this radical perspective, Deliberatio supra hymnum trium puerorum ad Isingrimum liberalem represents not only an impressive work of Christian apologetics but also a lucid apologetics of maximal moral and political values.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Deliberatio contains many interrogations which concern the status of philosophy: on the true philosophy, on the lack of identity between philosophy (as teaching of the heretics) and wisdom (sapientia), on the philosophy as teaching of “mortal” things, on the wise who worships only the truth etc.

- Gerard de Cenad, Armonia lumii sau tălmăcire a Cântării celor trei coconi către Isingrim Dascălul [The harmony of the world or interpretation of the Song of the three children to Isingrim the Teacher] (Bucharest: Meridiane, 1984), 97.

- Henri Focillon, Anul 1000 [The Year 1000] (Bucharest: Meridiane, 1971), 34.

- Constantin D. Rupa uses the expressions “inter-testamentary cohesion” and “inter-testamentary unit.” See “An 11th century philosophical treatise written in Banat and its surprising revelations about the local history,” in International Workshop on the Historiography of Philosophy: Representations and Cultural Constructions 2012, ed. Claudiu Marius Mesaros, Florin Lobont, György Geréby, Teodora Artimon (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013), 204.

- “… that treasure of wisdom belonging equally to ancients, Jews, and Christians, but which was fully understood only by the Apostles.” Ibidem.

- Gerard de Cenad, Armonia lumii, 89.

- Ibidem, 80, 109.

- At Cenad (Csanád), in the newly-founded Catholic diocese and “missionary bishopric” following Achtumʼs defeat ‒ and the placement of the Banat Voivodship, probably starting with 1030, under Hungarian suzerainty, in an impressive and difficult “missionary epopee” between 1038 and 1046. The newly established episcopate was used by the King Stephen I for the administrative, political, secular organization of the newly-conquered territory. See in this respect Florin Curta, “Transylvania around A. D. 1000,” in Europe Around the year 1000, ed. Przemyslaw Urbańczyk (Warsaw: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2001), 142 sq.

- Paul Vincent Spade, “Medieval Philosophy”, in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2009, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/medieval-philosophy/ (last time accessed: June 22, 2015).

- Ibidem.

- The Bishop of Cenad, having significant knowledge of physics and astronomy, was inspired by the works of the most important authors of Christian apologetic and patristic philosophy, particularly Gregory of Nyssa, St. Augustine, Boethius, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, Ian Scotus Eriugena.

- Dermot Moran, “John Scottus Eriugena”, in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2004, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scottus-eriugena/ (last time accessed: June 22, 2015); Carlos Steel and D. W. Hadley, “John Scotus Eriugena,” in A Companion to Philosophy in the Middle Ages, ed. Jorge J. E. Gracia and Timothy B. Noone (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2002),399.

- The Roman Catholic Bishop of Transylvania between 1780 and 1798, the first and most important among the exegetes of St. Gerard who highlighted his philosophical concerns in Sancti Gerardi Episcopi Chanadiensis, Scripta et acta hactenus inedita, cum Serie Episcoporvm Chanadiensivm, Albo-Carolinae, Typis Episcopalibus, 1790.

- Dermot Moran, “Nature, Man, and God in the Philosophy of John Scottus Eriugena,” in The Irish Mind, ed. R. Kearney (Dublin and New Jersey: Wolfhound Press and Humanities Press, 1985), 91. The initiator of Scholastic tradition in the West and also “the first great European mystic”, Eriugena, “stimulated by Saint Augustine”, developed an understanding of the cogito ”and a philosophy of subjectivity in which “the human subject is essentially mind” pursuing its own course of intellectual development and enlightenment. See Dermot Moran, The philosophy of John Scottus Eriugena. A study of idealism in the Middle Ages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), XII-XIII.

- Étienne Gilson, La philosophie au Moyen Age, I: De Scot Érigène a S. Bonaventure (Paris: Payot & CIE, 1922), 14.

- Joh. Scotus Eriugena, De divina praedestinatione liber, L, 1, 16, citing Augustine’s De uera religione 5, 8,apud Dermot Moran, “John Scottus Eriugena.”

- Gerard de Cenad, Armonia lumii, 98.

- Ibidem, 74, 87, 88, 90.

- Ibidem, 99. Rupa, “An 11th century philosophical treatise,” 197.

- Known at that time through Boethiusʼ early translation of Porphyrysʼ Isagore. Gerard, as well as his contemporaries, probably knew Porphyrysʼ work from a medieval epitome. Ibidem.

- Ibidem. Jean de Fécamp and his work the Liber meditationum Sancti Augustini (1028)is quoted.

- Gerardde Cenad, Armonia lumii, 74.

- Ibidem, 71.

- Ibidem 74.

- Ibidem, 79.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem, 150-151.

- Ibidem, 79.

- The reason forSt. Gerard’s addition to The Book of Daniel has been debated. The Prayer of Azariah or the Song of the Three Holy Children (Hananiah, Mishaʼel, and Azariah, by their Babylonian or Chaldean names Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego) was one of the (apocryphal) additions to Daniel (along with “Susannah and the Elders” and “Bel and the Dragon”), considered by the Catholic and Orthodox Churches a deuterocanonical book, one belonging to the second canon. The additions were considered parts of the Old Testament but are not part of the Hebrew Bible. Although the Book of Daniel was traditionally classified as prophetic, its literary style is considered today as apocalyptic, comprising apocalyptic prophecies on the end of the world, e.g.: the raising of a shameless king who will commit unbelievable devastations, will succeed in everything he begins, will destroy the mighty and the saintly people, will rise against the Lord of lords, and he will be crushed but not by human hand. It is the story of the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar who tried to introduce the worship of a new idol for the Jews. The Song of the three youths contains the lamentation regarding “the lawless people and the worst amongst ungodly ones, an unjust king, the worst on earth,” the unwavering faith in God and in His miracles, the angel of the Lord who descended and touched with dew whiff the flame of furnace where Azaria and his friends were and the worship and fervent blessing of God by the three happy saved.

- Gerard de Cenad, Armonia lumii, 80-81.

- Ibidem, 84.

- Ibidem, 107.

- Ibidem, 73.

- Ibid, 97.

- Ibid, 97.

- The year 1000 was named as such in his Historiae (Historiarum libri quinque ab anno incarnationis DCCCC usque ad annum MXLIV) by Raoul (Rodulfus) Glaber. Amongst other contemporary historians of the year 1000 were Adémar of Chabannes ‒ the author of Historiae and Chronicon Aquitanicum et Francicum ‒ and Theitmar of Meerseburg, who wrote Chronicon.

- That line of argumentation, developed by Henri Focillon in his reference book LʼAn Mil (Paris: Armand Colin, 1952)and, meanwhile, established as a commonplace of the literature, belongs to Adolf von Harnack, who formulated it in his article “Millenium” in Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol. 16 (9th ed., New York: Scribnerʾs, 1883), 314-318, in an exemplary configuration of the history of millenarian doctrine and of its philosophical and religious grounds. See:Henri Focillon, Anul 1000, 33.

- Among them Adolf von Harnack, Edmond Pognon, Henri Focillon, Leon Morris, John Barton, Vern Poythress.

- Henri Focillon,Anul 1000, 34.

- Ibidem.

- Ibid, 36.

- Richard Landes, “The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000: Augustinian Historiography, Medieval and Modern,” Speculum 75 (2000): 101

- See for these conceptual distinctions Richard Landes, “The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000,” 101.

- Ibidem, 97.

- And especially championed by Jules Michelet. See Jules Michelet, L’histoire de France (Paris, 1835), Vol. 2, 132, apud Richard Landes, “The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000,” 97.

- Summarized in 1901 by George Lincoln Burr as a new consensus among the American and European historians in relation to the thesis that the arrival of the year 1000 did not provoke any apocalyptic expectations. See George Lincoln Burr, “The Year 1000 and the Antecedents of the Crusades,” American Historical Review 6 (1901), 429-439, apud Richard Landes, “The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000,” 97.

- Richard Landes, “Apocalyptic Expectations around the Year 1000” 1, http://www.mille.org/scholarship/1000/1000-br.html (last time accessed: June 22, 2015).

- Georges Duby, L’an mil (Paris: Gallimard, 1980), 9.

- Richard Landes,“Apocalyptic Expectations around the Year 1000,” http://www.mille.org/scholarship/1000/1000-br.html (last time accessed:June22, 2015).

- Amongst them especially Marc Bloch, Lucien Febvre, Henri Focillon sau Edmond Pognon and the leading representatives of Annales: Georges Duby, Jacques Le Goff, Jean Delumeau, Philippe Aries, etc.

- See Richard Landes, “The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000,” 105.

- Richard Landes, “The Apocalyptic Year 1000: Then and Now,” 7, http://www.mille.org/scholarship/1000/1000then_now.html (last time accessed:June 22, 2015).

- The “two, fundamentally opposed stances about the nearness of the Apocalypse in any religion with a strong eschatological tradition like Christianity” are the “roosters and owls.” “Roosters crow the dawn is imminent, owls that the night is still young. In periods of rising apocalyptic expectation, the roosters crow in chorus, rousing and disturbing listeners sympathetic and hostile alike; the hoots of the owls are straw in the wind. After the failure of the apocalyptic expectations (historically one of the constants of apocalyptic moments ‒ they have all failed), the roosters are either soup or silent, and the owls dominate the discourse. Given the last laugh, the owls also dominate the documents and the archives, and in a religion whose elite is profoundly shaped by so towering an owl as Augustine, this translates into a documentary record ‒ particularly in periods of little writing and imperfect preservation ‒into a paltry record of apocalyptic expectation.” Richard Landes,“Apocalyptic Expectations around the Year 1000.”

- Richard Landes, “The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000,” 106.

- Georges Duby, L’an mil, 30.

- As that from 960, year in which the Lotharingian computists were predicting the end for the year 970,because the Annunciation and the Crucifixion coincided: Friday, March 25, when Adam was created, Isaac sacrificed, theRed Sea crossed, Christ Incarnated, Christ Crucified, and the Archangel Michael would defeat Satan.

- Richard Landes,“The Apocalyptic Year 1000.”

- Richard Landes, “The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000,” 102.

- Which take on a symbolic form when the sovereign, anointed of the Lord, imitates Jesus’ deeds during Easter.

- Richard Landes, “The Apocalyptic Year 1000”.

- Paul Magdalino,“The Year 1000 in Byzantium,” in The Medieval Mediterranean Peoples, Economies and Cultures, 400-1500, ed. Hugh Kennedy, Paul Magdalino, David Abulafia, Benjamin Arbel, Mark Meyerson, Larry J. Simon. Vol. 45 ‒ Byzantium in the Year 1000, ed. Paul Magdalino (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2003), 234-235.

- Ibidem, 241.

- Henri Focillon, Anul 1000, 39-40.

- Ibidem, 53.

- Georges Duby, L’an mil (Paris: Gallimard, 1980),16, 21

- Henri Focillon, Anul 1000, 52.

- Ibidem, 54.

- Gerard de Cenad, Armonia lumii, 99.

- Ibidem, 112.

- Like all centuries end, according to the theory of periodicity argued by Hillel Schwartz. See Hillel Schwartz, Century’s End: A Cultural History of the fin-de-siècle from the 990s to the 1990s (New York: Doubleday, 1990).

- C. A. Macartney, Hungary: A Short History (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1962), 8. http://mek.oszk.hu/02000/02086/02086.htm (last time accessed:June 22, 2015).

- Henri Focillon, Anul 1000, 118..

- Ibidem, 57.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem.

- In a favorable context in which Pope Sylvester II and Emperor Otto III were “remarkable figures” and had “a unique relationship” in which the Pope, Ottoʼs tutor, friend,and mentor, determined Otto to see his dreamed “renewed Empire” “as an oecumenical community of Christian nations and as a Germanic temporal dominion.”C. A. Macartney, Hungary: A Short History, 8.

- Richard Landes, “Apocalyptic Expectations around the Year 1000”, http://www.mille.org/scholarship/1000/ 1000-br.html (accessed March 27, 2015).

- Kees Teszelszky, “In Searchof Hungary in Europe: An Introduction,” in A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699, ed. Gábor Almási, Szymon Brzeziński, Ildikó Horn, Kees Teszelszky and Áron Zarnóczki, Vol. 3 The Making and Uses of the Image of Hungary and Transylvania, ed. Kees Teszelszky (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014), 6.

- See Paul Stephenson, “The Balkan Frontier in the Year 1000,” in The Medieval Mediterranean Peoples, Economies and Cultures, 400-1500, ed. Hugh Kennedy, Paul Magdalino, David Abulafia, Benjamin Arbel, Mark Meyerson, Larry J. Simon. Vol. 45 Byzantium in the Year 1000, ed. Paul Magdalino (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2003), 109-110.

- Henri Focillon, Anul 1000, 126.

- Gerard de Cenad, Armonia lumii, 79.

- Ibidem,80.

- Ibid, 80-81.

- Ibid, 136.

Bibliography

- Curta, Florin.“Transylvania around A. D. 1000.” In Europe around the year 1000, ed. Przemyslaw Urbańczyk, 141-165. Warsaw: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2001.

- Duby, Georges. L’an mil. Paris: Gallimard, 1980.

- _____.L’Europe au Moyen Âge. Paris: Flammarion, 1984.

- Focillon, Henri.Anul 1000 [The Year 1000], Trans. Tudor Ţopa. Bucharest: Meridiane, 1971.

- Gerard de Cenad. Armonia lumii sau tălmăcire a cântării celor trei coconi către Isigrim Dascălul [The harmony of the world or interpretation of the Song of the three children to Isingrim the Teacher], trans. Radu Constantinescu.Bucharest: Meridiane, 1984.

- Heitzman, James, Wolfgang Schenkluhn, ed. The World in the Year 1000. Lanham, Maryland/Oxford: University Press of America, 2004.

- Landes, Richard. “The Apocalyptic Year 1000: Then and Now”, http://www.mille.org/scholarship/1000/1000then_now.html (last time accessed:June 22, 2015).

- _____. “Apocalyptic Expectations around the Year 1000”, http://www.mille.org/scholarship/1000/1000-br.html (last time accessed:June 22, 2015).

- _____. “The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000: Augustinian Historiography, Medieval and Modern,” Speculum 75 (2000): 97-145.

- Macartney, C. A. Hungary: A Short History. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1962. http://mek.oszk.hu/02000/02086/02086.htm (last time accessed:June 22, 2015).

- Magdalino, Paul. “The Year 1000 in Byzantium.” In The Medieval Mediterranean Peoples, Economies and Cultures, 400-1500, ed. Hugh Kennedy, Paul Magdalino, David Abulafia, Benjamin Arbel, Mark Meyerson, Larry J. Simon. Vol. 45 Byzantium in the Year 1000, ed. Paul Magdalino, 233-271. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2003.

- Moran, Dermot. “Nature, Man, and God in the Philosophy of John Scottus Eriugena.” In The Irish Mind, ed. R. Kearney, Dublin and New Jersey: Wolfhound Press and Humanities Press, 1985, 91-106.

- Rupa, Constantin D. “An 11th century philosophical treatise written in Banat and its surprising revelations about the local history.” In International Workshop on the Historiography of Philosophy: Representations and Cultural Constructions 2012, ed. Claudiu Marius Mesaros, Florin Lobont, György Geréby, Teodora Artimon (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013), 196-203.Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013.

- Schwartz, Hillel. Century’s End: A Cultural History of the fin-de-siècle from the 990s to the 1990s. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

- Stephenson, Paul. “The Balkan Frontier in the Year 1000.” In The Medieval Mediterranean Peoples, Economies and Cultures, 400-1500, ed. Hugh Kennedy, Paul Magdalino, David Abulafia, Benjamin Arbel, Mark Meyerson, Larry J. Simon. Vol. 45 Byzantium in the Year 1000, ed. Paul Magdalino, 109-133. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2003.

- Teszelszky, Kees. “In Search of Hungary in Europe: An Introduction.” In Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699, ed. Gábor Almási, Szymon Brzeziński, Ildikó Horn,Kees Teszelszky and Áron Zarnóczki. Vol. 3 The Making and Uses of the Image of Hungary and Transylvania, ed. Kees Teszelszky, 1-15. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014.

Originally published by Trivent Publishing in Saint Gerard of Cenad: Tradition and Innovation (2015) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.