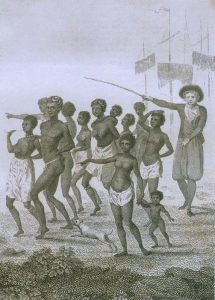

Captives being brought on board a slave ship on the West Coast of Africa (Slave Coast), c1880. Although Britain outlawed slavery in 1833 and it was abolished in the USA after the defeat of the Confederacy in the Civil War in 1865, the transatlantic trade in African slaves continued. The main market for the slaves was Brazil, where slavery was not abolished until 1888. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

By Dr. Mary Battle

Public Historian, Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture

Co-Director of the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative.

College of Charleston

Atlantic World Context

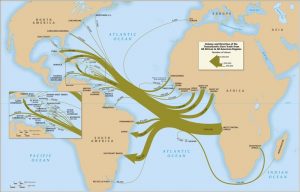

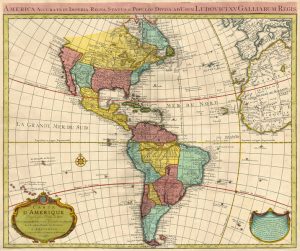

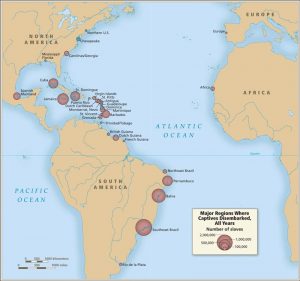

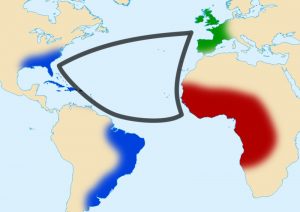

Map of volume and direction of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, courtesy of David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

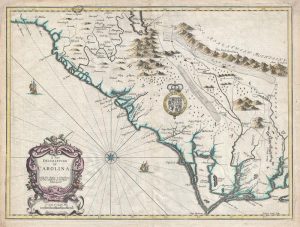

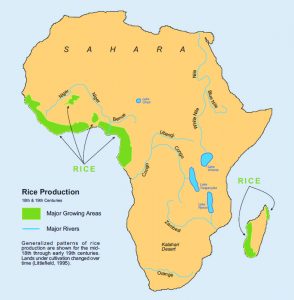

Slavery, plantation agriculture, and the major cash crop of rice all came to Charleston and the surrounding Lowcountry region through a larger Atlantic World trade and migration system. To fully comprehend Charleston’s colonial and antebellum history of slavery, trade, and plantations, we must look beyond the city, region, and even North America, to include the trans-Atlantic exchanges and influences of a complex multicultural and multinational network.

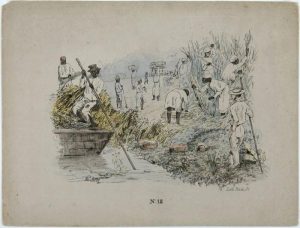

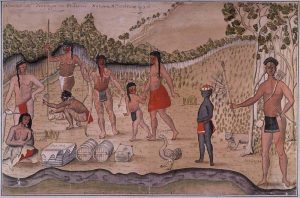

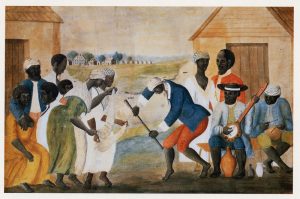

Slave traders in Gorée, Senegal, by Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, ca. eighteenth century.

Before the fifteenth century, the Atlantic Ocean proved to be a barrier between the populations and cultures of West and Central Africa, Western Europe, and the Americas. Though southern Europeans and northern Africans along the Mediterranean Sea shared a long history of interaction through trade or conflict, African and European maritime trading networks did not extend along the Atlantic coast of Africa into the continent’s western and central regions until the fifteenth century. Ancient overland trade networks between Europe and western and central Africa have a much longer history, but they did not match the volume and speed of later maritime routes. By improving overseas navigation in the fifteenth century, European explorers and entrepreneurs rapidly increased trade and multicultural exchanges with Atlantic African populations ranging from small nations and kinship groups to complex African empires.

The Slave Ship, Slavers throwing overboard the Dead and Dying — Typhoon coming, painting by J.M.W. Turner, 1840, courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

By the end of the fifteenth century, European explorers could navigate difficult currents and winds to not only travel down the coast of Africa, but also to cross the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas. Their goal was to find a western trade route to Asia because the growing Ottoman Empire blocked the eastern route. Instead, these explorers encountered the Americas, and in the centuries that followed the Atlantic Ocean transformed from a barrier into a corridor of trade and migration — both voluntary and forced. New trans-Atlantic maritime routes launched an unprecedented level of interaction between Africans, American Indians, and western Europeans.

European and American Indian fur traders in Canada, drawing by William Faden, 1777, courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada.

The numerous encounters, conflicts, and collaborations that resulted from these interactions became known as the Columbian Exchange or the Grand Exchange — a massive movement of animals, plants, human populations, diseases, and ideas that would forever transform the diverse nations and societies of the Atlantic World. While the traditional labor systems, religious beliefs, military rivalries, and social hierarchies of these formerly separate Atlantic World regions remained influential in the New World, each cultural group also underwent dramatic changes in emerging multicultural colonial contexts.

United States Slave Trade, engraving, 1830, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In the fifteenth century, Europeans seeking economic gain through trade, colonial expansion, mining, and plantation agriculture effectively launched this massive Atlantic World exchange. To make their various economic pursuits in the Americas profitable on growing trans-Atlantic markets, elite and entrepreneurial Europeans required land, widespread trading networks, and significant labor resources. They displaced American Indians from their traditional territories to access new land, and developed labor systems like European indentured servitude and African and American Indian slavery to fill their growing labor needs. For many Africans and American Indians, new encounters with Europeans in the Atlantic World meant conflict and oppression.

Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, image by Sylvia Frey, ca. 2000s. During the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, ships disembarked enslaved Africans on Sullivan’s Island for quarantine in “pest houses,” before they were sold in Charleston markets.

Still, American Indians and Africans proved far from passive in this New World transformation process. In the Americas, Africans and American Indians consistently resisted European-imposed racial hierarchies and enslavement, and carved out spaces for their own political, social, economic, spiritual, and cultural needs and identities. In this way, the diverse cultural groups of the Atlantic World each played significant roles in shaping the multicultural societies that emerged in the coming centuries. Today, the history of the Atlantic World cannot be fully understood without including the multicultural experiences and influences of American Indians, Africans, and Europeans, formed through collaboration and exchange, as well as conflict and oppression, in the New World.

The growth of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas, primarily for people of African descent, exemplifies how older labor systems and racial beliefs transformed with New World economic, political, and social developments.

Map of North America, the West Indies, and the Atlantic Ocean, by P. Mortier, 1693.

Slavery before the Trans-Atlantic Trade

Roman collared slaves, marble relief, Smyrna (present day Izmir, Turkey), 200 A.D., courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum.

Various forms of slavery, servitude, or coerced human labor existed throughout the world before the development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in the sixteenth century. As historian David Eltis explains, “almost all peoples have been both slaves and slaveholders at some point in their histories.” Still, earlier coerced labor systems in the Atlantic World generally differed, in terms of scale, legal status, and racial definitions, from the trans-Atlantic chattel slavery system that developed and shaped New World societies from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

Slavery in West and Central Africa

Mansa Musa in Catalan Atlas, drawn by Abraham Cresques of Mallorca, 1375, courtesy of the British Library. Mansa Musa was the African ruler of the Mali Empire in the 14th century. When Mansa Musa, a Muslim, took a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 he reportedly brought a procession of 60,000 men and 12,000 slaves.

Slavery was prevalent in many West and Central African societies before and during the trans-Atlantic slave trade. When diverse African empires, small to medium-sized nations, or kinship groups came into conflict for various political and economic reasons, individuals from one African group regularly enslaved captives from another group because they viewed them as outsiders. The rulers of these slaveholding societies could then exert power over these captives as prisoners of war for labor needs, to expand their kinship group or nation, influence and disseminate spiritual beliefs, or potentially to trade for economic gain. Though shared African ethnic identities such as Yoruba or Mandinka may have been influential in this context, the concept of a unified black racial identity, or of individual freedoms and labor rights, were not yet meaningful.

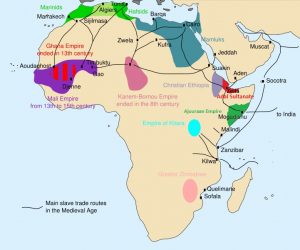

Map of Main slave trade routes in Medieval Africa before the development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, 2012.

West and Central African elites and royalty from slaveholding societies even relied on their kinship group, ranging from family members to slaves, to secure and maintain their wealth and status. By controlling the rights of their kinship group, western and central African elites owned the products of their labor. In contrast, before the trans-Atlantic trade, western European elites focused on owning land as private property to secure their wealth.

Slaves being transported in Africa, engraving from Lehrbuch der Weltgeschichte oder Die Geschichte der Menschheit, a book by William Rednbacher, 1890.

They held rights to the products produced on their land through various labor systems, rather than owning the laborers as chattel property. Land in rural western and central African regions (outside of densely populated or riverine areas) was often open to cultivation, rather than divided into individual landholdings, so controlling labor became a greater priority. The end result in both regional systems was that elites controlled the profits generated from products cultivated through laborers and land. The different emphasis on what or whom they owned to guarantee rights over these profits shaped the role of slavery in these regions before the trans-Atlantic trade.

Cowry shells, photograph, 2005. Cowry shells were often used as currency in different African slave trades.

Scholars also argue that West Africa featured several politically decentralized, or stateless, societies. In such societies the village, or a confederation of villages, was the largest political unit. A range of positions of authority existed within these villages, but no one person or group claimed the positions of ruler or monarchy. According to historian Walter Hawthorne, in this context, government worked through group consensus. In addition, many of these small-scale, decentralized societies rejected slaveholding.

Map of major cultural areas in the Americas before European contact, 2007.

Blue = Arctic

Light Blue = Northwest

Dark Green = Aridoamerica

Orange = Mesoamerica

Light Green = Isthmo-Colombian

Yellow = Caribbean

Red = Amazon

Brown = Andes

Gray = Migratory or Small Farming Societies

As the trans-Atlantic slave trade with Europeans expanded from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, however, both non-slaveholding and slaveholding West and Central African societies experienced the pressures of greater slave trade demand. In contrast to the chattel slavery that later developed in the New World, an enslaved person in West and Central Africa lived within a more flexible kinship group system. Anyone considered a slave in this region before the trans-Atlantic trade had a greater chance of becoming “free” within a lifetime; legal rights were generally not defined by racial categories; and an enslaved person was not always permanently separated from biological family networks or familiar home landscapes.

The rise of plantation agriculture as central to Atlantic World economies from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries led to a generally more extreme system of chattel slavery, where human beings became movable commodities bought and sold in mass numbers across significant geographic distances. New World plantations also generally required greater levels of exertion than earlier labor systems, so that slaveholders could produce a profit within competitive trans-Atlantic markets.

Slavery in the Americas

Pyramid ruins in Yaxzhilan, an ancient Mayan city in Chiapas, Mexico, 2005. Maya was a hierarchical Mesoamerican civilization established ca. 1500-2000 BC. The Mayan social hierarchy included captive or tribute laborers who helped build structures such as pyramids.

In the centuries before the arrival of European explorers, diverse American Indian groups lived in a wide range of social structures. Many of these socio-political structures included different forms of slavery or coerced labor, based on enslaving prisoners of war between conflicting groups, enforcing slavery within the class hierarchy of an empire, or forced tribute payments of goods or labor to demonstrate submission to a leader. However, like West and Central African slavery, American Indian slavery generally functioned within a more fluid kinship system in contrast to what later developed in the New World.

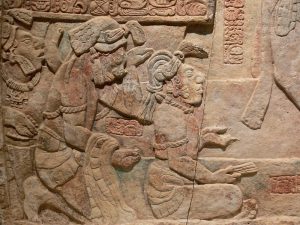

Limestone carving of captives being presented to a Mayan ruler, Usumacinta River Valley, Mexico, ca. A.D. 785, courtesy of Kimbell Art Museum.

Ultimately, the practice of slavery as an oppressive and exploitative labor system was prevalent in both Western Africa and the Americas long before the influence of Europeans. Still, the factors that defined the social, political, and economic purposes and scale of slavery significantly changed, expanded, and intensified with the rise of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and American plantation agriculture launched by European expansion. For these reasons, African and American Indian slavery before the trans-Atlantic trade differed significantly from the chattel slavery systems that would later develop in the Atlantic World.

The Decline of Slavery in Western Europe

Serfs in feudal England, on a calendar page for August, Queen Mary’s Psalter, ca. 1310, courtesy of the British Library Manuscripts Online Catalogue.

In contrast to other Atlantic World regions, slavery was not prevalent in Western Europe in the centuries before the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Instead, labor contracts, convict labor, and serfdom prevailed. This had not always been the case. During the Roman Empire and into the early Middle Ages, enslaved Europeans could be found in every region of this subcontinent. After the Roman Empire collapsed (starting in 400 A.D. in northern Europe), the practice of individual Europeans owning other Europeans as chattel property began to decline.

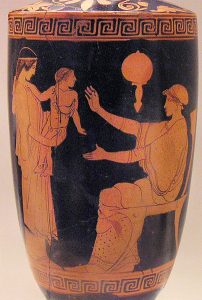

A Greek slave presents a baby to its mother, vase from Eretria in Ancient Greece, 470-460 B.C., courtesy of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, Greece.

As described in the following sections, this decline occurred due to unique religious, geographic, and political circumstances in Western Europe. By 1200, chattel slavery had all but disappeared from northwestern Europe. Southern Europeans along the Mediterranean coast continued to purchase slaves from various parts of Eastern Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. In Lisbon, for example, African slaves comprised one tenth of the population in the 1460s. Overall, however, the slave trade into southern Europe was relatively small compared to what later developed in the New World.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, western European elites began to focus on acquiring and controlling land, and the goods produced on the land they owned, rather than controlling laborers through slavery to accumulate goods. The European labor systems that began to replace slavery should not be confused with modern free labor, but serfdom, convict labor, and contract systems did grant workers access to rights that were denied to slaves. For example, European serfs were bound to work for the lord of a manor, but in return the lord provided protection and land that serfs could farm for their own subsistence. While serfs did not own the land they worked, they could not be sold away from it like chattel slaves. Instead, serfs were bound to whichever lord currently owned the manor. By the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, serfdom declined in Western Europe due to population changes and economic shifts resulting from the Black Death. Hiring contract laborers became more profitable for landowners in Western Europe and as a result, European laborers gained greater control over their own labor and mobility.

European Christianity and Slavery

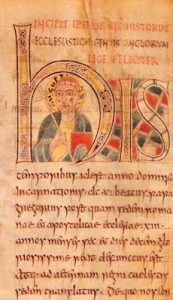

St. Augustine of Canterbury from the Saint Petersburg Bede, ca. 731-746 A.D., courtesy of the National Library of Russia. St. Augustine was a Benedictine monk from Rome who was sent on a mission to England in 595 A.D. to convert Anglo-Saxon pagans to Christianity. He became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in 597 A.D.

Before New World expansion, concepts of race and racial hierarchies did not define who could and could not be enslaved in Western Europe. Instead, the spread of Christianity in the Early Middle Ages (from the fifth to tenth centuries) marked the boundaries of slavery throughout Europe. Historian David Brion Davis argues that the Judeo-Christian belief in a monotheistic God who rules over a homogenous group of people generally prevented European Christians from enslaving one another. As more western Europeans converted to Christianity, this unified religious identity enabled the decline of slavery in Europe, but allowed other rigid social and labor hierarchies to remain. By 1500, European Christians believed slavery was a more devastating punishment than execution for criminals and prisoners of war. Still, European Christians did not object to the enslavement of non-Christians, particularly due to ongoing conflicts between Christians and non-Christians within Europe, in the nearby Islamic World, and later in West and Central Africa (which also included Muslim regions) and the Americas.

St. Patrick in stained glass window, image by Andreas F. Borchert, Church of Our Lady, Star of the Sea, and St. Patrick in Goleen, County Cork, Ireland, 2009. According to legend and some document evidence, St.Patrick was born in Roman Britain as a Christian in the late 4th century. When he was sixteen years old he was captured and sent to Ireland as a slave. He escaped back to England, but later became a cleric and returned to Ireland to spread Christianity. By the 7th century, he was the patron saint of Ireland.

In northwestern Europe, non-Christian, or “pagan,” Vikings regularly raided coastal towns for slaves from the fifth to the eleventh centuries. The Norman Conquest of England in 1066 helped protect some areas from these slave raids, but tensions and conflicts continued between Christian and non-Christian Europeans. Even after many Irish Celts converted to Christianity starting in the fifth century, English Christians deemed them inferior, based on the suspicion that their religious practices still contained non-Christian rituals. This sense of Christian superiority helped the English justify Irish colonization in the centuries to come.

The Christian Crusades of the High and Late Middle Ages waged against Islamic kingdoms in the eastern Mediterranean, western Asia, and northern Africa, also helped form a division between Christians and Muslims. The expansion of Islam in the fifteenth century through the Ottoman Empire (which encompassed parts of southeastern Europe, North Africa, Western Asia, and the Middle East by the sixteenth century) further fueled religious conflicts before the trans-Atlantic trade. In addition, from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries, Barbary corsairs (or pirates) raided European coastal towns and enslaved European Christians for Islamic slave trade markets. Ultimately, even with the protection of church law, European Christians were familiar with the threat of enslavement.

Emperor Frederick II, a Christian crusader from Italy, meets al-Kamil, Muslim ruler of Egypt, during the Sixth Crusade (1228-29), from a manuscript of the Nuova Cronica by Giovanni Villani, ca. 1341-48.

In response to these conflicts, a series of fifteenth century popes argued for the enslavement of non-Christians as “an instrument for Christian conversion.” According to church law, Christians were protected from slavery, but Muslim “infidels” and non-Christian “pagans” were acceptable to enslave. Similarly, in Islamic law, only non-Muslims could be enslaved. While Jewish populations living in Christian-dominated Western Europe were protected from slavery in the Middle Ages, widespread anti-Semitic prejudices amongst European Christians led to Jewish persecution, exile, violent massacres, and even accusations of causing the Black Death.

In the New World, the criteria for enslavement increasingly shifted from non-Christian to non-European. As Europeans began emphasizing religious, racial, and ethnic differences between themselves and American Indians and Africans, this boundary moved further, from non-European to non-“white,” particularly to enable the enslavement of “black” Africans and their African American descendants.

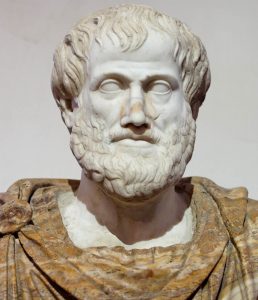

Aristotle, marble bust is a Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Lysippos from 330 B.C., courtesy of the National Museum of Rome. Aristotle produced writings about slavery and “natural” social hierarchies that influenced prominent Christian theologians such as Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century. Later theologians used Aristotle’s argument for “natural slaves” to justify New World slavery.

The recovery of classical Greek texts before and during the European Renaissance also provided philosophical and theological justification for a Christian social hierarchy that included slavery. For example, the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 BC to 322 BC) produced writings about slavery that influenced prominent Christian theologians such as Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century, and later provided legal and moral justifications for implementing slavery based on a racial hierarchy in the sixteenth century. Aristotle argued that the master and slave relationship was “natural” and that “some are marked out for subjection, others for rule.” Aquinas built on Aristotle’s argument to assert that the slave was the physical instrument of his owner. This condition allowed a slave owner to claim everything his or her slaves possessed and produced, including their children. Aquinas attributed the plight of enslavement to sin and the inevitable conditions of a sinful world. Other theologians before and during the Renaissance emphasized Aristotle’s belief in a natural order, but asserted that, “some men were slaves by their very nature.”

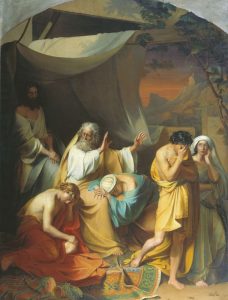

The Curse of Ham, painting by Ksenofontov Ivan Stepanovitch, ca. 1817-1875. According to 16th and 17th century theologians, Africans could be enslaved because they believed they were the descendants of Ham, a Christian biblical figure cursed into slavery by his father, Noah.

Based on this evolving theology, European Christians initially saw non-Christians as “natural slaves.” With New World expansion, however, Europeans came to primarily associate Africans with the institution of slavery. To explain this racial shift from a Judeo-Christian worldview, sixteenth and seventeenth century theologians merged Aristotle’s theory of “natural slaves” with the biblical Curse of Ham. According to this interpretation, Africans are the descendants of Ham and Canaan, who Noah cursed into slavery for Ham’s transgressions (Ham is Noah’s son and Canaan’s father). Though the Bible does not mention race or skin color in this narrative, according to these sixteenth and seventeenth century theologians, Africans inherited Ham and Canaan’s curse of slavery. By the nineteenth century, pro-slavery advocates in the United States continued to use this misleading biblical justification, as well as Aristotle’s theory of natural order and New World racial prejudices, to defend their support of slavery.

Freedom, Slavery, and Race in the New World

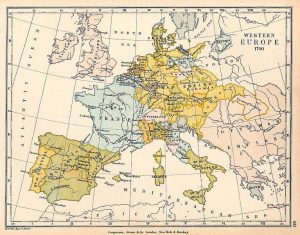

Map of Western Europe, 1700, courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, University of Texas at Austin. Map demonstrates close geographic promixity of Western European nations that formed after the decline of the Roman Empire.

In addition to the spread of Christianity, western Europeans did not enslave other Europeans by the late fifteenth century because of a relatively equal and stable balance of power. Various nation states connected to the Atlantic Ocean, including England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Spain, rose to power within close geographic proximity of one another. The ongoing wars and competition between and within these nation states meant that no single government had enough central authority to control commercial expansion or enslave the population of another state or their own citizens.

Harbor scene depicting Portuguese ships preparing to depart from Lisbon, engraving by Theodore de Bry, 1593, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The tenuous power balance that grew between nations made it possible for western Europeans to collectively prevent enslavement. In contrast to Africa and the Americas, this unique set of geographic, economic, and religious circumstances allowed western Europeans to maintain basic rights over their own labor and physical mobility, rather than having these rights determined by their national or ethnic status. Though Europeans still operated within rigid class, gender, and labor hierarchies, western European laborers developed and maintained the ability to not live as the property of another human being in the centuries before New World expansion.

Christopher Columbus at the royal court of Spain, painting by Václav Brožik, 1884, courtesy of the Library of Congress. Columbus was an Italian explorer who received funding from the Catholic Spanish monarchy to sail west from Europe in 1492 in search of an alternative trade route to Asia. Though Columbus was not the first European in the Americas, his four trans-Atlantic voyages launched lasting European awareness of the Americas, and interest in colonial expansion.

This increased individual mobility for many Europeans marked an early beginning to modern understandings of freedom in the Atlantic World. Still, individual rights and free labor would not effectively emerge as influential political and social concepts in the Atlantic World until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Whether through individual choice or through migration forced by political and religious conflicts (such as the Protestant Reformation or Jewish persecution), western Europeans found that these historic circumstances allowed for greater mobility outside of the geographic or social boundaries of their nation or kinship group. While populations throughout the world demonstrated significant technology and skill in maritime navigation, western Europeans possessed the additional social and labor mobility to explore and establish long-term Atlantic trade on a large scale. They also had the motive. The constant warfare between and within nations in Western Europe proved costly, and European nations struggled with a chronic shortage of gold and silver. In addition, Western Europe experienced a shortage of labor due to the plague, or “Black Death” that killed over thirty percent of Europeans at its height in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Individual traders and commercial entrepreneurs increasingly pursued additional sources of wealth and labor outside of their native countries through trade and expansion, often with the support of financially depleted monarchies.

Omne Bonum, created by James le Palmer, London, England, ca. 1360-1375, courtesy of the British Library. Image depicts victims of the Black Death being blessed by a priest. The significant population loss caused by the plague in the 13th and 14th centuries led to labor shortages and economic instability in Europe, as well as new opportunities for individual mobility and entrepreneurship.

As European explorers and entrepreneurs established profit-seeking settlements in the Americas, they needed labor to cultivate or mine their new properties. If they could not obtain this labor by employing European indentured servants (particularly when the labor was arduous or deadly), Europeans increasingly acquired enslaved laborers through military attacks or trade within systems of slavery in Africa and the Americas.

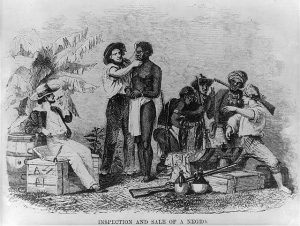

“Inspection and Sale of a Negro,” wood engraving originally published in Captain Canot; or, Twenty Years of an African Slaver, by Brantz Mayer, 1854. Image depicts an African man being inspected by a European while another European talks with African slave traders.

Initially, the religions practiced by the indigenous populations in Africa and the Americas provided adequate justification for their capture and enslavement, but what happened when Africans or American Indians converted to Christianity? European slaveholders in the New World began to justify slavery by constructing the concept of a white European race as separate and superior to non-European races to avoid possible enslavement themselves.

New World Racism

Germanic warriors as depicted in Philip Clüver’s Germania Antiqua, 1616, courtesy of Yale University Library’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Drawing demonstrates perceptions of “barbarians” or “savages” during the Roman Empire. Romans believed “barbarian” groups in Europe such as the Germani or Gauls were childlike, sexually promiscuous, and mentally and physically inferior. Similarly degrading stereotypes would reemerge from Europeans about Africans and American Indians with European expansion into the New World.

Early forms of western European racial prejudice first began between Europeans. Ancient Greeks described “other” European groups, such as Scythians and Celts, as barbarians and savages. They often defined their prejudices based on physical preferences for certain bodily and facial features, including lighter skin, and discouraged intermarriage. Greek scholars such as Hippocrates attributed place and climate as the defining factors in shaping different physical appearances, and they additionally argued that certain physical traits signified mental and behavioral inferiority. Ancient Romans believed that being “civilized” marked their superiority, both physically and mentally, over the Gauls and Germani of Europe. By the Middle Ages, European Christians also stigmatized the color “black,” and associated it with sin and death. The darker skin of European laborers who worked outside with sun and wind exposure led elites to link skin color and darkness to servitude, long before New World slavery. During later divisions and conflicts throughout Europe, combatants continued to claim physical and mental superiority over their opponents to justify military and labor subjugation. For example, during the British conquest of Ireland in the sixteenth century, the English monarchy characterized the Gaelic Irish as morally and physically inferior, as well as darker skinned, in comparison to the “civilized” English population.

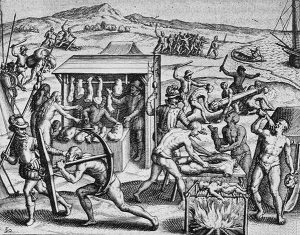

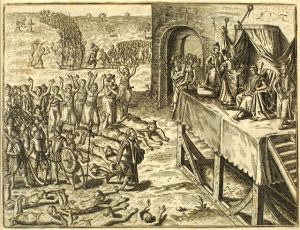

Depiction of Spanish explorers exploiting American Indians in South America, as recounted by Bartolomé de las Casas in Narratio Regionum indicarum per Hispanos Quosdam devastatarum verissima, drawing by Theodor de Bry, 16th century, courtesy of the Newberry Research Library.

European concepts of conquest combined religious prejudices and stereotypes of physical and mental inferiority to justify subjugation as a “civilizing” force. These conquest ideologies took on a major economic purpose with New World expansion, when Europeans used physical and religious differences to justify the large-scale enslavement of Africans and displacement of American Indians for labor in plantations and mines. Notably, as the economic incentives for subjugation increased, European racial stereotypes about Africans became more derogatory. As historian Ira Berlin notes, Europeans during New World expansion initially characterized West and Central Africans as “sly, cunning, deceptive . . . perhaps too clever.”

Portrait of an African Man, painting by Jan Mostaert, ca. 1525-1520, courtesy of Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. Painting demonstrates Atlantic Creole influences, and how early depictions of Africans by Europeans were not necessarily derogatory before the increase of racial stereotypes with New World chattel slavery.

These stereotypes were not unlike the stereotypes Europeans made about one another, and they reveal a begrudging sense of equal competition rather than white superiority. With the rise of African slavery in the New World, Europeans shifted these stereotypes to support a racial hierarchy where Africans and African Americans were depicted as animalistic, servile, unintelligent, and sexually promiscuous. As Berlin explains, “the nature of slavery – the relationship of black and white – determined the character of racial ideas.” New World racism developed to justify New World slavery.

Over time, this racial boundary of “white superiority,” and the belief that Africans and American Indians belonged to inferior races, grew to influence European social, political, legal, and labor systems throughout Atlantic World societies. However, shared white racial privileges did not mean conflicts between European nations ceased. The French and the English, for example, proved more than willing to repeatedly go to war with one another. Despite ongoing conflicts, neither nation was willing to enslave one another or their own citizens based on their prior history of competitive balance, and a growing sense of white racial superiority over non-Europeans.

Europe Supported By Africa and America, engraving by William Blake, from John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam in Guiana on the Wild Coast of South America, 1796.

Enslaved Africans and American Indians consistently resisted their secondary status within this developing racial hierarchy, and many began to demand access to the labor and mobility rights enjoyed by Europeans in the Americas. They enacted this resistance in a range of ways, including running away, open rebellion, and warfare. In response, European slaveholders in the Americas enacted rigid laws to enforce racial hierarchies and subjugation, and used tactics of violent coercion to secure chattel slavery. By the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, these racial hierarchies became systemically entrenched throughout American social structures and institutions. Freedom became associated with white Europeans and their Euro American offspring, while slavery became associated with non-whites, particularly people of African descent.

Depiction of a slave insurrection in the British colony of Demerara (now Guyana) on August 18, 1823, created by Joshua Bryant, 1823, courtesy of John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. This rebellion helped draw international attention to the atrocities of slavery in the British Empire, and bolstered the British anti-slavery movement.

Still, this racial barrier between slave and free never became absolute. Instead, in the centuries to come, oppressive racial boundaries in various Atlantic World contexts were challenged, violently reasserted, and eventually overthrown and redefined. During the Age of Emancipation in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, chattel slavery legally came to an end throughout the Atlantic World through a combination of abolition movements, slave rebellions, and in the case of the United States, civil war. Even after emancipation, Atlantic World societies continued to struggle with the unjust legacies of this institution, particularly during twentieth century civil rights movements. But as historian Ira Berlin asserts, “that [racism] could be made in the past argues that it could be remade in the future.” Racism is not a permanent fixture of human societies. Instead, as Atlantic World history reveals, it is a social construction built through constantly changing historic circumstances. Racism can be challenged, changed, and undone.

Plantations and the Trans-Atlantic Trade

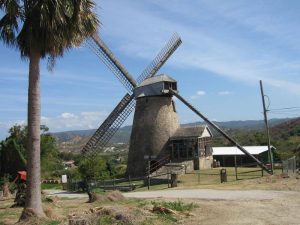

Map of Madeira, island off the coast of West Africa, created by F. de Wit, ca. 17th century. Madeira featured early examples of sugar plantations owned by Europeans and worked through enslaved African labor. This cash crop agriculture and enslaved labor model would eventually spread throughout the Atlantic World.

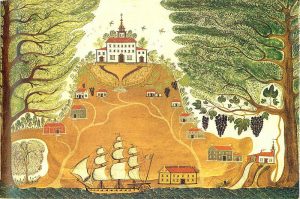

European maritime expansion across the Atlantic Ocean first began with Norse voyages to Iceland and Greenland in the ninth and tenth centuries. But the first European establishment of long distance maritime trade and settlement in the Atlantic World began in the fourteenth century, when explorers from Mediterranean and Atlantic European countries began trading with islanders off the western coast of Africa (such as the Canary, Cape Verde, Madeira, and Azores islands). Eventually western European entrepreneurs and settlers followed Atlantic explorers to these islands to establish early sugar plantations and trading outposts.

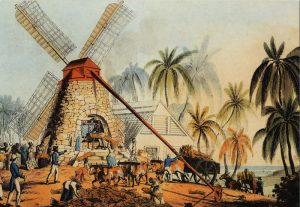

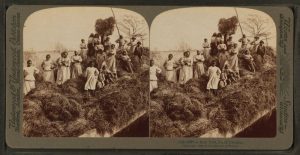

Sugar processing on the English colony of Antigua, drawing by William Clark, 1823, courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. From African Atlantic islands, sugar plantations quickly spread to tropical Caribbean islands with European expansion into the New World.

Europeans enslaved islanders or imported enslaved Africans acquired through trade with the nearby West and Central African coast. In this way, African Atlantic islands became home to some of the earliest examples of the plantation agricultural complex and enslaved African labor system that would come to dominate the Atlantic World.

Sugarcane, created by Franz Eugen Köhler, from Köhler’s Medizinal-Pflanzen, 1897.

These plantations developed from Mediterranean farming systems that focused on growing cash crops for trade rather than on subsistence crops for local use. Europeans first encountered many of their major cash crops, such as sugar, through exposure to Muslim agriculture during the Crusades (from the eleventh to thirteenth centuries). Sugarcane particularly appealed to Europeans because their only sweetener before that time had been honey. They could also use sugar to make alcoholic beverages, such as rum or Madeira. But growing sugarcane required access to tropical lands not found in northern Europe, and processing and transporting sugar throughout Europe required significant labor and trading resources. Sugar also did not have the nutritional value to be a staple crop for local consumers, like wheat or rice. Instead it was a supplemental, luxury good that had to be grown for a widespread consumer base to become a profitable cash crop. This launched a demand for long-distance trade networks, as well as significant labor and land resources. For these reasons, the expanding European sugar market particularly fueled the rise of plantation-style agriculture, cash crop trading, and plantation slavery throughout the Atlantic World.

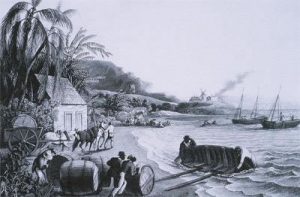

Loading sugar and molasses for shipping to England from Barbados, ca. 18th century, courtesy of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. Sugar required extensive maritime trade networks to become a lucrative cash crop.

When Europeans settled areas in the Americas where sugarcane could not grow, or when they had to adjust to a competitive sugar market, they found that they could adapt the plantation model and coerced labor structure to capitalize on other cash crops, such as tobacco, indigo, cotton, and rice, that also had a large consumer market appeal.

Considering the close proximity of Africa, why did Europeans not colonize and establish plantations on the nearby West and Central African mainland, rather than spending valuable resources to cross the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas?

Ultimately most Central and Western African nations and empires were militarily too strong for extensive European occupation. Leaders of these African regions often proved willing to trade goods and enslaved Africans, and they even established military alliances with Europeans in outpost settlements, but they resisted and generally prevented widespread European colonization during the early stages of New World expansion.

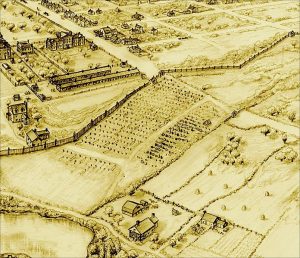

Slaves working on a tobacco plantation in 17th century Virginia, by an unknown artist, 1670. In areas where sugar was not a cash crop, European settlers used the plantation and slave labor model to cultivate other cash crops, such as tobacco.

In addition, Europeans lacked immunities to many tropical diseases, which encouraged them to settle on islands or the coast rather than in the African interior. The strength of the Ottoman Empire blocked European expansion east of the Mediterranean, which also forced Europeans in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to look west for commercial growth and colonization. Driven by profit seeking and labor intensive ventures such as plantations and mines, Europeans transformed the Atlantic Ocean from a barrier into a highway for transporting goods, settlers, indentured servants, and enslaved laborers. Plantation agriculture and cash crop trading played a central role in fueling European expansion into the New World, and in developing chattel slavery, primarily of Africans, in the Americas.

New World Labor Systems: American Indians

Depiction of a tobacco wharf in colonial America, detail from 18th century map of the Chesapeake Bay, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

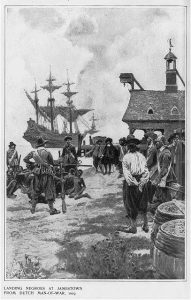

The primary goal of European expansion and colonization was to acquire land and resources to produce exports to sell for profit on the growing trans-Atlantic market. Profitable production demanded significant labor resources. The elite and entrepreneurial western Europeans who settled in the Americas sought laborers to cultivate cash crops, mine for precious metals, tend livestock, provide domestic service, and work in various artisanal trades. The labor sources they drew from to fill this demand included European indentured servants and convicts, free and enslaved American Indians, and enslaved Africans purchased through the developing trans-Atlantic slave trade. This meant that early colonial labor forces in the Americas were often a mix of Europeans, American Indians, and Africans. In large plantation areas, however, enslaved Africans and their African American offspring increasingly became the dominant laboring population. This section outlines how various historic factors led to African slavery taking a central role in supplying labor and skills to develop New World plantations and economies.

American Indian Encounters

American Indians giving a talk to Colonel Bouquet in a conference at a Council Fire, near his Camp on the Banks of Muskingum in North America in 1764, engraving by C. Grignion, 1766.

American Indian populations, cultures, and societies varied greatly across the Western Hemisphere at the time of European contact and colonial expansion. These regional variations influenced the types of encounters different European groups had with American Indians. In Mesoamerica and the central Andes, for example, the highly centralized and hierarchical nature of indigenous societies facilitated their incorporation into the Spanish empire after conquistadors defeated local rulers and replaced them at the top of socio-political systems.

Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci leads an attack on Amerindians on the island of “Ity” (location uncertain, possibly Bermuda), on his first journey to the New World in 1497, engraving by Theodor de Bry, ca. 1592.

In New Spain, colonial authorities relied on the pre-existing native practices and networks to exercise power over local populations. In contrast, Europeans struggled to subjugate American Indians living in more decentralized societies. In northern Mexico, the Chichimecas resisted Spanish conquest longer than their Aztec neighbors because their nomadic lifestyle and fluid leadership structures made them difficult targets to subdue. Europeans who settled on the shores of North and South America faced similar challenges.

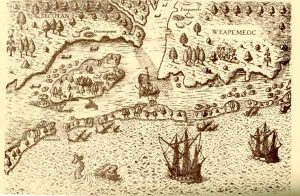

Arrival of the Englishmen in North Carolina, from Richard Hakluyt, The Discourse Concerning Westerne Planting, ca. 1585. Map includes names of American Indian groups already settled on the coast that would become the Carolina colony, including the Secotan and Weapemoec.

In the seventeenth century, European colonists in New England and New France, for example, interacted with American Indian nomads and farmers who lived in egalitarian communities headed by a leader or group of leaders. While Europeans often referred to these individuals as “kings” and “captains,” their power was often temporary and limited. Unlike monarchs in Western Europe, American Indian leaders in these communities ruled by persuasion rather than inheritance. In this context, Europeans acquired land either through complex negotiations or perpetual warfare with American Indians, until native groups could be dispersed or pacified.

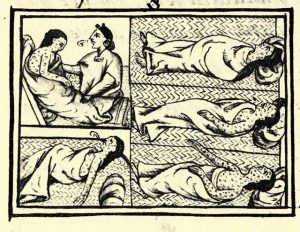

Nahuas of conquest-era central Mexico suffering from smallpox, drawing accompanying text in Book XII of theFlorentine Codex, ca. 1585.

In various cases, small numbers of Europeans initially negotiated with various American Indians, but once the colonial population and resources increased, their expansion strategies shifted from negotiation to conflict. In areas such as Canada, where the fur trade was the dominant economic objective for the French, violent conflict between American Indians and European newcomers was often avoided to improve trade negotiations.

Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, painting by Felix Parra, 1875, courtesy of the Museo Nacional de Arte in Mexico City, Mexico. Bartolomé de las Casas (ca. 1484-1566) was a Dominican friar who was one of the first Spanish settlers in the Americas. He opposed the atrocities Europeans inflicted against American Indian groups, including slavery, and advocated to European leaders that Africans be enslaved instead of American Indians. This helped ingnite the trans-Atlantic slave trade to Iberian colonies. Later in life he redacted these views and saw all forms of slavery as wrong.

Throughout North and South America, epidemics played a central role in determining the power dynamic between Europeans and American Indians. In contrast to Africans on the Atlantic Coast, who could prevent significant European expansion through both military strength and stronger resistance to tropical diseases, American Indians totally lacked immunity to the infections and viruses Europeans brought with them to the New World.

Scholars estimate that millions of American Indians died or experienced weakened health due to rapid exposure to European diseases. In addition, Europeans brought new weaponry and horseback mobility for their military attacks, which also led to significant population loss amongst native groups throughout the Americas and the Caribbean. Even when American Indian populations began to rebound from devastating epidemics, the weakening of their societal structures and military strength allowed Europeans to dominate or displace American Indians from their traditional territories in the Americas.

In the process of displacing indigenous groups, Europeans also attempted to enslave American Indians through military coercion and trade for captives from inter-Indian conflicts. In some areas of South America and Mexico, enslaved or coerced American Indians formed a significant part of the labor force. In North America, however, attempts to enslave American Indians on a large scale proved to be less successful. Though some American Indians did work for Europeans as free laborers, indigenous captives could escape more easily because of their familiarity with the local landscape and their ability to gain assistance from nearby kin (in contrast to enslaved Africans who were transplanted to a foreign landscape).

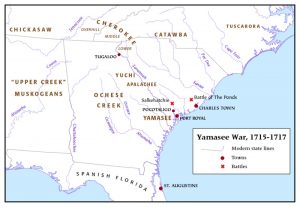

Map overview of the Yamassee War, 2007. The Yamassee War in the Carolina colony (1715-1717) stemmed from growing tensions between American Indians and English settlers, particularly over trade disagreements, land encroachments, and the enslavement of American Indians.

In areas where Europeans needed to establish peaceful relations with American Indians for trading, or where European and indigenous settlements coexisted in close proximity, enslaving American Indians threatened to destabilize alliances. For example, the Yamassee War in the Carolina colony (1715-1717) partially resulted from disagreements over trade and misunderstandings between English colonists and American Indians over the nature of slavery. In addition, some European monarchs and religious leaders began to denounce enslaving American Indians, which further encouraged Euro American colonists to look to indentured European or enslaved African labor.

New World Labor Systems: European Indentured Servants

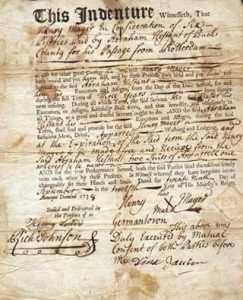

Indenture contract, signed with an ‘X’ by Henry Meyer, 1738.

Until the early eighteenth century, the majority of Europeans who came to the Americas were not free settlers or elite landholders — they were indentured servants. In exchange for the cost of ship passage across the Atlantic, young men and women from throughout Western Europe came to the Americas to work in a range of labor roles, from skilled trades to plantation agriculture. To pay for the cost of their travel, indentured servants worked for several years for a contract holder who did not pay wages, but did provide housing, food, and clothing.

Advertisement for indentured servants, Virginia Gazette, 28 March 1771.

Similar to enslaved American Indians and Africans, indentured servants could have their contracts sold at market to different bidders, could be physically punished, and in some contexts, servants were not allowed to marry or have children without the permission of their contract holder. Labor and disease conditions for early colonial indentured servants were also brutal, and many died before the end of their contract. Attempting to flee their servitude could lead to punishment and added years to their contract. In addition, while many indentured servants came willingly to the Americas due to periods of low wages and poor living conditions in Western Europe, significant numbers were also kidnapped, or transported as convict labor.

Spaniard and Mulatto, painting by Miguel Cabrera, 1763. Painting depicts a racially mixed family in Latin America.

Despite some similarities to enslavement, indentured servants ultimately attained their freedom once they completed their contract, while enslaved people were permanently denied their freedom unless they could obtain the means to purchase themselves or successfully escape. In addition, in the seventeenth century various European colonies established laws ensuring that the offspring of enslaved women inherited their legal status from their mother, even if their father was free. Although intermarriage and sexual relationships between free European women and enslaved African or American Indian men did occur (particularly during early settlement), social stigmas and white male-dominated race and gender hierarchies meant that many interracial sexual relationships, both forced and willing, occurred between free or indentured European men and enslaved African or American Indian women. For this reason, a law linking enslavement to the mother’s status effectively made slavery inheritable in the Americas.

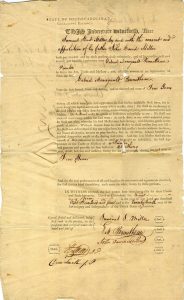

Samuel Miller apprenticeship indenture, 1805, courtesy of the South Carolina Historical Society. Samuel Stent Miller apprenticed himself to Gabriel Manigault Bounetheau, a Charleston, South Carolina printer, for a period of five years. Gabriel Manigault Bounetheau was a Justice of the Peace, Clerk of Council, and a printer with an office at 3 Broad Street, according to the Charleston City Directory of 1806. Miller’s indenture reflects a less arduous position reserved for whites by the eighteenth century.

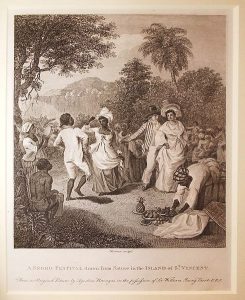

For European indentured servants, the guarantee of eventual freedom was significant, but many still collaborated with enslaved Africans and American Indians to run away, resist cruel treatment from shared masters, or to form rebellions. The close proximity of social status sometimes led to intermarriage between European indentured servants and enslaved Africans, and the exchange of cultural traditions and skills in the form of food, music, spirituality, and craft. Such interaction, including forced and willing sexual relationships, also occurred between elite slaveholding whites and enslaved people, but these relationships operated within the more coercive and imbalanced power dynamic of slaveholder and enslaved.

By the eighteenth century, however, European indentured servants became more scarce and expensive to obtain. Fewer Europeans were willing to accept undesirable contracts in the Americas, particularly after rumors spread of the deadly conditions on American plantations. Elites in the Americas began to offer lighter labor treatment and special privileges to white indentured servants and free, non-slaveholding whites over enslaved Africans and American Indians. This extension of white racial privilege increasingly gave indentured and non-slaveholding Europeans an incentive to build stronger alliances with white elites.

The Burning of Jamestown, painting by Howard Pyle, 1905, courtesy of Canadian Libraries. During Bacon’s Rebellion (1676-77), Nathanial Bacon organized Virginia settlers across race and class divisions to protest against the rule of Governor William Berkeley. On September 19, 1676, they burned the colonial capital of Jamestown, Virginia to the ground. The alliance between European indentured servants and enslaved Africans during the rebellion disturbed the ruling class, who subsequently passed laws to harden Virginia’s racial caste system dividing free and indentured whites from enslaved blacks.

In exchange, slaveholding elites benefitted from a class of non-slaveholding whites who provided a protective buffer to help maintain developing race and class hierarchies in the Americas. For example, non-slaveholding whites could serve on patrols to help protect against slave rebellions, particularly as the numbers of enslaved Africans and African descendants in the Americas increased with the continued growth of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and Atlantic plantation economies. In regions where enslaved Africans held a numerical majority, white elites promoted multi-tiered racial hierarchies. In these areas, enslaved or free people with lighter skin tones (often due to mixed European, African, or American Indian ancestry) received milder labor treatment or special privileges over dark-skinned enslaved Africans to again generate a protective buffer class to secure the institution of slavery.

New World Labor Systems: African Slavery

Portrait of an African Slave Woman, painting by Italian painter Annibale Carracci, ca. 1580s.

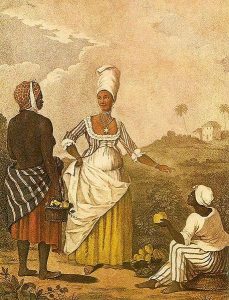

Europeans colonizing the Americas in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries frequently brought both enslaved and free African laborers with them, drawn from pre-existing trading relationships in West and Central Africa. The legal and social status of these early Africans in the Americas was generally more fluid than what developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as New World chattel slavery became more entrenched. In addition, many early Africans in the Americas came from African port cities involved in European trade and later the trans-Atlantic trade. Known as Atlantic Creoles, these Africans had prior exposure to Europeans such as the Portuguese, who had been trading and settling along the African Atlantic coast since the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Some Atlantic Creoles had even lived in Europe. Early Atlantic World multicultural exchanges also influenced European identities. For example, Portuguese sailors in African port cities often adapted their Iberian culture to West African contexts, and they became known as Lançados. The offspring of Portuguese and African sexual relationships and intermarriage, who then permanently settled in African regions, became known as Euroafricans.

Group of Negroes, As Imported to Be Sold for Slaves, engraving by William Blake, from John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative of a five years’ Expedition, against the revolted Negroes of Surinam, 1796, courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

From this prior exposure to African and European influences, Atlantic Creoles in the Americas often spoke multiple languages; practiced Christianity infused with African religious traditions and even Islam; and had experience working with Europeans as interpreters, sailors, merchants, and traders. When slave traders forced them into early American labor systems, Atlantic Creoles could use their familiarity with European customs to negotiate the terms of their status more easily than later enslaved arrivals from the African interior. In this way, a significant number of enslaved Atlantic Creoles in the Americas obtained their freedom, married and had children born into freedom (often with other European settlers), and became property owners, farmers, and even slaveholders.

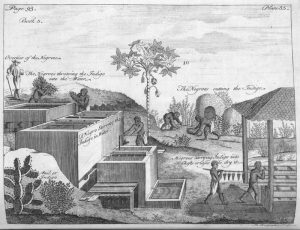

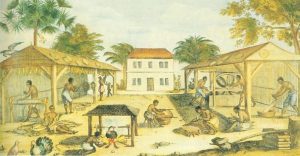

Indigo Manufacture in French West Indies, from Pierre Pomet, “A complete history of drugs,” 1748, courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections Library. The market success of plantation cash crops such as sugar, tobacco, rice, indigo, and cotton greatly increased labor demands and solidified economic reliance on slavery.

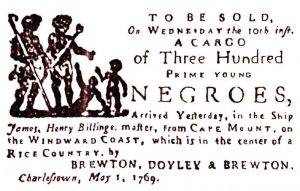

The experiences of enslaved and free Africans in the Americas changed dramatically once plantation agriculture became more established in the late seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. The market success of plantation cash crops such as sugar, tobacco, rice, indigo, and cotton greatly increased labor demands and solidified economic reliance on slavery. As described earlier, complications with maintaining populations of enslaved American Indians and European indentured servants meant that plantation owners turned to African slavery as their central labor source. The economic success of New World cash crops ensured that plantation owners accumulated more capital to invest in both slave labor and land.

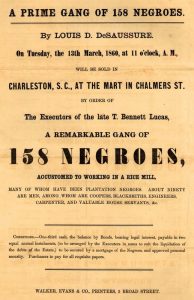

Advertisement for “A Prime Gang Of 158 Negroes,” Louis D. DeSaussure, Charleston, South Carolina, 1860, courtesy of Duke University Libraries. By 1860, “Negroes” implied slaves in this Charleston, South Carolina, advertisement.

To fill this growing American labor demand, slave traders in Africa expanded beyond port areas to the interior to obtain more captives. In contrast to earlier Atlantic Creoles, these new African arrivals had less exposure to European customs and languages. While manumission was still a possibility for slaves throughout the Americas, greater cultural differences and communication barriers, combined with greater investments in plantation agriculture and chattel slavery, made it more difficult for enslaved Africans in the Americas to negotiate their labor status.

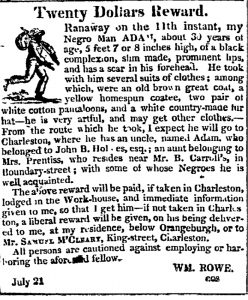

During the eighteenth century, Africans and their African American offspring became the dominant enslaved population in the Americas. In major plantation areas, their numbers were so great that they became the population majority. Though the specific legal rights, social experiences, manumission possibilities, and labor treatment of enslaved Africans varied greatly over time and across different regional, colonial, and economic contexts, the rise of plantation agriculture meant that African slavery became central to many colonial American economies. To ensure their financial success, American slaveholders influenced political, legal, and social systems to limit both the mobility and the possibility of freedom for growing numbers of enslaved Africans and their offspring. They increasingly defended this oppression using arguments of white superiority, black inferiority, and natural racial hierarchies, and in doing so established institutionalized racism throughout the Americas.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

Map of volume and direction of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, courtesy of David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, New Haven: Yale University Press 2010.

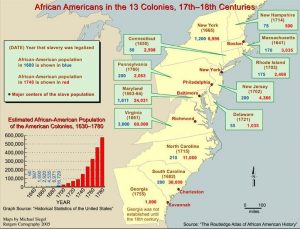

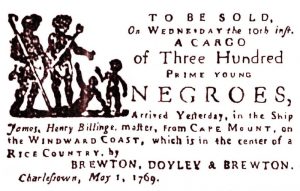

The trans-Atlantic slave trade was the largest long-distance forced movement of people in history. From the sixteenth to the late nineteenth centuries, over twelve million (some estimates run as high as fifteen million) African men, women, and children were enslaved, transported to the Americas, and bought and sold by European slaveholders as chattel property to be used for their labor and skills.

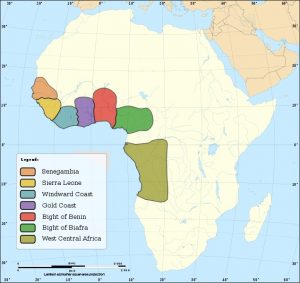

Map depicting major trans-Atlantic slave trading regions in West and Central Africa, 2011.

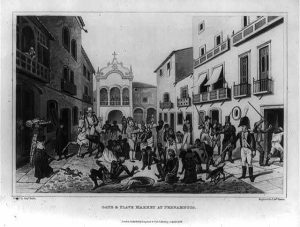

The trans-Atlantic slave trade occurred within a broader system of trade between West and Central Africa, Western Europe, the Caribbean, and North and South America. At African ports, European traders exchanged metals, cloth, beads, guns, and ammunition for captive Africans brought to the coast from the African interior. Many captives died just during the long overland journeys (the slave coffle) from the interior to the coast. European traders then held these enslaved Africans in fortified slave castles such as Elmina in the central region (now Ghana), Goree Island (now in present day Senegal), and Bunce Island (now in present day Sierra Leone), before forcing them into ships for the Middle Passage across the Atlantic Ocean.

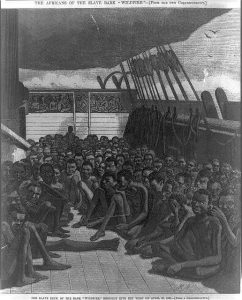

Engraving of the slave deck of the “Wildfire,” ship brought into Key West on April 30, 1860, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Scholars estimate that from ten to nineteen percent of the millions of Africans forced into the Middle Passage across the Atlantic died due to rough conditions on slave ships. Those who arrived at various ports in the Americas were then sold in public auctions or smaller trading venues to plantation owners, merchants, small farmers, prosperous tradesmen, and other slave traders. These traders could then transport slaves many miles further to sell on other Caribbean islands or into the North or South American interior. Predominantly European slaveholders purchased enslaved Africans to provide labor that included domestic service and artisanal trades. The majority, however, provided agricultural labor and skills to produce plantation cash crops for national and international markets. Slaveholders used profits from these exports to expand their landholdings and purchase more enslaved Africans, perpetuating the trans-Atlantic slave trade cycle for centuries, until various European countries and new American nations officially ceased their participation in the trade in the nineteenth century (though illegal trans-Atlantic slave trading continued even after national and colonial governments issued legal bans).

Establishing the Trade

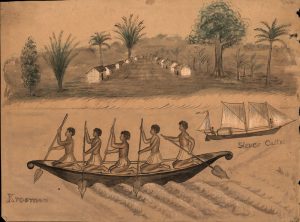

Large Canoe and Village Scene, possibly Liberia, mid-19th century, courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections Library. Example of shallow water vessels used in West and Central Africa to counter European attacks and thwart early attempts at mainland colonization.

In the fifteenth century, Portugal became the first European nation to take significant part in African slave trading. The Portuguese primarily acquired slaves for labor on Atlantic African island plantations, and later for plantations in Brazil and the Caribbean, though they also sent a small number to Europe. Initially, Portuguese explorers attempted to acquire African labor through direct raids along the coast, but they found that these attacks were costly and often ineffective against West and Central African military strategies.

Manikongo (leaders of Kongo) receiving the Portugeuse, ca. pre-1840. The Portuguese developed a trading relationship with the Kingdom of Kongo, which existed from the 14th to the 19th centuries in what is now Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Civil War within Kongo during the trans-Atlantic slave trade would lead to many of its subjects becoming captives traded to the Portugeuse.

For example, in 1444, Portuguese marauders arrived in Senegal ready to assault and capture Africans using armor, swords, and deep-sea vessels. But the Portuguese discovered that the Senegalese out-maneuvered their ships using light, shallow water vessels better suited to the estuaries of the Senegalese coast. In addition, the Senegalese fought with poison arrows that slipped through their armor and decimated the Portuguese soldiers. Subsequently, Portuguese traders generally abandoned direct combat and established commercial relations with West and Central African leaders, who agreed to sell slaves taken from various African wars or domestic trading, as well as gold and other commodities, in exchange for European and North African goods.

Slave Raid on village in Senegal in the 1780s, drawing by René Claude Geoffroy de Villeneuve, 1814, courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections Library.

Over time, the Portuguese developed additional slave trade partnerships with African leaders along the West and Central African coast and claimed a monopoly over these relationships, which initially limited access to the trade for other western European competitors. Despite Portuguese claims, African leaders enforced their own local laws and customs in negotiating trade relations. Many welcomed additional trade with Europeans from other nations.

The Slave Trade, painting by Francois Auguste Biard, 1840, courtesy of the Wilberforce House Museum.

When Portuguese, and later their European competitors, found that peaceful commercial relations alone did not generate enough African slaves to fill the growing demands of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, they formed military alliances with certain African groups against their enemies. This encouraged more extensive warfare to produce captives for trading. While European-backed Africans had their own political or economic reasons for fighting with other African enemies, the end result for Europeans traders in these military alliances was greater access to enslaved war captives. To a lesser extent, Europeans also pursued African colonization to secure access to slaves and other goods. For example, the Portuguese colonized portions of Angola in 1571 with the help of military alliances from Kongo, but were pushed out in 1591 by their former allies. Throughout this early period, African leaders and European competitors ultimately prevented these attempts at African colonization from becoming as extensive as in the Americas.

Fight between two privateering vessels, the French Confiance and the HMS Kent, painting by Ambroise-Louis Garneray, ca. 1783–1857.

The Portuguese dominated the early trans-Atlantic slave trade on the African coast in the sixteenth century. As a result, other European nations first gained access to enslaved Africans through privateering during wars with the Portuguese,rather than through direct trade. When English, Dutch, or French privateers captured Portuguese ships during Atlantic maritime conflicts, they often found enslaved Africans on these ships, as well as Atlantic trade goods, and they sent these captives to labor in their own colonies.

Elimina Castle, or St. George Castle, Gold Coast (present day Ghana), from the Atlas Blaeu van der Hem, 1665-1668. The Portugeuse established Elmina on the Gold Coast as a trading settlement in 1482. It eventually became a major slave trading post in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The Dutch seized the fortress from the Portugeuse in 1637.

In this way, privateering generated a market interest in the trans-Atlantic slave trade across European colonies in the Americas. After Portugal temporarily united with Spain in 1580, the Spanish broke up the Portuguese slave trade monopoly by offering direct slave trading contracts to other European merchants. Known as the asiento system, the Dutch took advantage of these contracts to compete with the Portuguese and Spanish for direct access to African slave trading, and the British and French eventually followed. By the eighteenth century, when the trans-Atlantic slave trade reached its trafficking peak, the British (followed by the French and Portuguese) had become the largest carriers of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic. The overwhelming majority of enslaved Africans went to plantations in Brazil and the Caribbean, and a smaller percentage went to North America and other parts of South and Central America.

African Participation and Resistance to the Trade

Map of West Africa, created by Johann Baptist Homann, 1743.

With some early exceptions, Europeans were not able to independently enter the West and Central African interior to capture Africans and force them onto ships to the Americas. Instead, European traders generally relied on a network of African rulers and traders to capture and bring enslaved Africans from various coastal and interior regions to slave castles on the West and Central African coast. Many of these traders acquired captives as a result of military and political conflict, but some also pursued slave trading for profit.

Mossi horsemen, created by J.W. Buel, 1890. The Mossi Kingdoms resisted the trans-Saharan slave trade and slave raiding from the Ghana, Mali, and Songhai Empires in West Africa, but with the expansion of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, they became involved in slave trading in the 1800s.

Scholars provide various explanations for why African traders were willing to supply enslaved Africans to Europeans for the trans-Atlantic trade. By the early sixteenth century, slavery already played a major role in some western and central African societies, and contributed to maritime slave trade systems across the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Subsequently, some historians argue that Europeans in the Atlantic took advantage of a pre-existing slave trade system in Africa to obtain labor for expanding plantation economies in the Americas. During the development of the trans-Atlantic trade, West and Central Africa consisted of diverse political and social structures, ranging from large empires to small states, and these groups often conflicted over internal politics as well as economic expansion.

Manillas from Nigeria, commonly used as currency in West Africa during the trans-Atlantic slave trade, particularly by European traders on the coast purchasing enslaved people from African traders.

As noted earlier, though ethnic identities were influential, these groups did not share a common “African” or “black” identity. Instead, they saw cultural and ethnic differences (such as Igbo, Ashanti, Mende, and Fulani) as social divisions. Frequent conflicts between these groups produced captives who could then circulate in the local slave trade system, and eventually the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Europeans also went to great lengths to influence African traders and leaders to provide enslaved Africans for the trans-Atlantic trade. European traders encouraged African consumer demands for European goods, formed military alliances to instigate fighting and increase the number of captives, and shifted the location of disembarkation points for the trade along the West and Central African coast to follow African military conflicts. In areas of West and Central Africa where slavery was not prevalent, European demand often expanded the presence of the institution and trade. But European traders still generally worked within terms set by African rulers and traders, who negotiated their own interests in these trading and military alliances.

“Door of No Return” memorial at The House of Slaves, Gorée, Senegal, image taken 2004.

For example, when the profits of the slave trade did not outweigh the loss of local labor caused by the trans-Atlantic trade, African leaders could refuse to supply European demands. Still, the pressures from European consumer interests in African slavery were great, and the social instability that followed military conflicts inevitably challenged the resources of African groups. Many Africans turned to the trans-Atlantic slave trade to expel their opponents or to garner profits. The population loss and disruptive effects on social, political, military, and labor systems caused by the trans-Atlantic slave trade varied in scale depending on the African region and group. As a result, scholars still debate the long-term impacts of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in West and Central Africa.

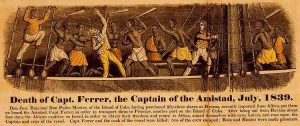

“Death of Capt. Ferrer, the Captain of the Amistad, July 1839,” engraving and frontispiece from John Warner Barber, A History of the Amistad Captives, 1840. The rebellion on the slave ship Amistad in 1839 was one of the most famous in U.S. history because the Supreme Court ruled that the Mende on board should have their freedom restored.

Regardless, the suffering of separated families and the experiences of enslavement during the trans-Atlantic trade were universally devastating for victims of the trans-Atlantic slave tradeThroughout the trade, the Africans who were enslaved or threatened with enslavement consistently resisted the dehumanizing confines of this institution.

Villages and towns built fortifications and warning systems to prevent attacks from traders or enemy groups. If captured and forced onto ships for the Middle Passage, enslaved Africans resisted by organizing hunger strikes, forming rebellions, and even committing suicide by leaping overboard rather than living in slavery. Scholars believe that roughly one slaving voyage in every ten experienced major rebellions. These rebellions were costly for European traders, and led them to avoid certain regions known for this resistance strategy, such as Upper Guinea, except during periods of high slave trade market demand. This resulted in fewer Africans entering the trans-Atlantic slave trade from these regions, which suggests that African resistance strategies could be effective.

The Middle Passage

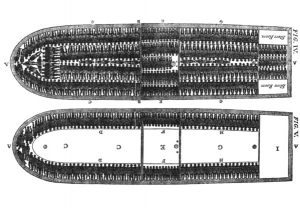

Diagram of a slave ship from the Atlantic slave trade, ca. 1790-91, courtesy of Lilly Library of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana University.

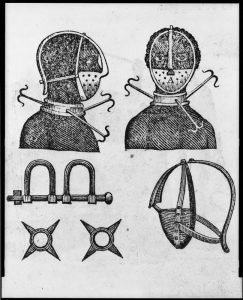

The conditions for enslaved Africans crossing the Atlantic Ocean in the Middle Passage were brutal and deadly. “Slaver” ships were specifically designed for maximizing the numbers of African men, women, and children that slave-trading captains and their crews could bring to the Americas. Once on board, crewmembers segregated enslaved Africans by gender and then chained and packed them closely together in ship holds. Captives then endured up to several months of extreme temperatures, harsh weather, filthy living conditions, and contagious diseases in these ship holds as they crossed the Atlantic Ocean. Roughly twenty-six percent of Africans who endured the Middle Passage were classified as children; captains chained men for the longest periods to prevent rebellion; and enslaved women often suffered sexual assault from crewmembers. The conditions on slaver ships were so harsh and unbearable that from thirteen to nineteen percent of Africans died in the Middle Passage.

Mortality rates were particularly high during the first few centuries of the trans-Atlantic trade, before shipping technology improved to shorten the length of the overall voyage. Though the ocean passage may only last a few weeks, the overall Middle Passage often took months because European slave captains lengthened the voyage by making stops in various African ports to seek more slaves to fill their ship hold. They also made numerous stops in American ports to attempt to sell their enslaved cargo at the best prices. Different points of disembarkation and arrival also influenced the arduous ship conditions for enslaved Africans. While the few voyages sailing from Upper Guinea could make a passage to the Americas in three weeks, the average duration from all regions of Africa was just over two months.

Set of iron leg shackles used in the trans-Atlantic slave trade from Africa to North America, 18th century, courtesy of the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture.

The conditions that millions of Africans endured during the Middle Passage into Amerian slavery stands as one of the greatest examples in history of human beings inflicting dehumanizing suffering on fellow human beings. As British abolitionist William Wilberforce (1759-1833) stated, “Never can so much misery be found condensed in so small a place as in a slave ship during the Middle Passage.” In the holds of slave ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean, millions of enslaved Africans first experienced what it meant to be defined and treated as chattel property in the context of New World slavery.

Conclusion

The Slave Ship, Slavers throwing overboard the Dead and Dying — Typhoon coming, painting by J.M.W. Turner, 1840, courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

By overcoming barriers in maritime technology in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, European navigators connected the Atlantic World through their travels down the African coast and finally across to the Americas. The trade and settlement routes they established launched a New World of multicultural interactions, exchanges, and conflicts between Africans, American Indians, and Europeans. They also unleashed new and constantly changing definitions of freedom, slavery, and race that would forever alter diverse societies throughout the Atlantic World. Though the institution of slavery has long been a part of human history, European western expansion, New World plantation agriculture, and the trans-Atlantic slave trade all tied this ancient coerced labor system to new extremes of economic profit, oppressive racial categories, and intensive labor regimes.

Olaudah Equiano, aka Gustavus Vassa, ca. 18th century, courtesy of Project Gutenberg. Equiano became a prominent abolitionist in England after he escaped from slavery and published The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The Africanin 1789.

Despite the dehumanizing experience of American chattel slavery from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, enslaved people consistently resisted the terms of their status and generated their own social, political, spiritual, and cultural identities. They also challenged and defied the false racial beliefs used to justify their status, and demanded access to the developing rights and freedoms that had been reserved mainly for elite Europeans and European Americans in the New World. The extremes of chattel slavery in the Americas made the ideals and benefits of individual freedom apparent, particularly to enslaved people. During the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, an eruption of rebellions, revolutions, and emancipation movements occurred throughout the Atlantic World to uproot seemingly entrenched systems of slavery. But even with the downfall of chattel slavery in the nineteenth century, the legacies of this institution – which include systemic racism, class divisions, unjust labor systems, and various ongoing forms of slavery – still persist throughout the modern Atlantic World.

“To the Friends of Negro Emancipation”, an engraving from the West Indies, celebrating the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, 1833.