How these fictional figures became wondrous screens on which to project theories of geographical, racial, and taxonomical difference.

By Dr. Vaughn Scribner

Associate Professor of British American History

University of Central Arkansas

For much of the eighteenth century, Western intellectuals chased after tritons and mermaids. Vaughn Scribner follows the hunt, revealing how humanity’s supposed aquatic ancestors became wondrous screens on which to project theories of geographical, racial, and taxonomical difference.

This article, Mermaids and Tritons in the Age of Reason, was originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it please see: https://publicdomainreview.org/legal/.

On May 6, 1736, the polymath Benjamin Franklin informed readers of his Pennsylvania Gazette of a “Sea Monster” recently spotted in Bermuda, “the upper part of whose Body was in the Shape and about the Bigness of a Boy of 12 Years old, with long black Hair; the lower Part resembled a Fish”. Apparently, the creature’s “human Likeness” inspired his captors to let it live. A 1769 issue of the Providence Gazette similarly reported that crew members of an English ship off the coast of Brest, France, watched as “a sea monster, like a man” circled their ship, at one point viewing “for some time the figure that was in our prow, which represented a beautiful woman”. The captain, the pilot and “the whole crew, consisting of two and thirty men” verified this tale.1

The above examples are quite representative of what an early modern Briton would have found in the newspapers. That these interactions were even reported tells us much. Intelligent men like Benjamin Franklin considered such encounters legitimate enough to spend the time and money to print in their widely read newspapers. By doing so, printers and authors helped sustain a narrative of curiosity surrounding these wondrous creatures. As a Londoner sat down with his paper (perhaps in the aptly named Mermaid Tavern) and read of yet another instance of a mermaid or triton sighting, his doubt might have transformed into curiosity.2

Philosophers’ debates over mermaids and tritons in this period reveal their willingness to embrace wonder in their larger quest to understand the origins of humankind. Naturalists used a wide range of methodologies to critically study these odd hybrids and, in turn, assert the reality of merpeople as evidence of humanity’s aquatic roots. As with other creatures they encountered in their global travels, European philosophers utilized various theories — including those of racial, biological, taxonomical, and geographic difference — to understand merpeople’s and, by proxy, humans’ place in the natural world.3

Westerners’ combination of curiosity and imperial expansion is well reflected in the cultural relevance of merpeople. Wealthy individuals and philosophical societies funded naturalists’, botanists’, and cartographers’ expeditions to the New World in the hope that they might broaden humanity’s understanding of the world and their place in it. In an expanding number of investigations into mermaids and tritons, naturalists demonstrated a growing penchant for the wondrous. They also, importantly, revealed how the process of scientific research had drastically changed over the last two hundred years. Rather than relying strictly on ancient texts and hearsay, eighteenth-century naturalists mustered various “modern” resources — global correspondence networks, erudite publication opportunities, transatlantic travel, specimen procedures, and learned societies — to rationally examine what many considered fantastical. Thus, a growing body of gentlemen both carried on and eschewed the supposed narrative of enlightened logic by applying well-known, valid research methods to mysterious merpeople. In doing so, eighteenth-century philosophers such as Cotton Mather, Peter Collinson, Samuel Fallours, Carl Linnaeus, and Hans Sloane complicated our — and their contemporaries’ — conceptions of science, nature, and humanity. The smartest men in the Western world, in short, spent much of the eighteenth century chasing merpeople around the globe.4

The Royal Society of London proved key in this endeavour, acting as both a repository and producer of legitimate scientific investigation. Sir Robert Sibbald, a respected Scottish physician and geographer, well understood the Society’s desire for ground-breaking research. On November 29, 1703 he wrote to Sir Hans Sloane, the president of the Society, to inform the London gentleman that Sibbald and his colleagues had been recording an account of Scotland’s amphibious creatures, along with accompanying copper-plate images, which he hoped to dedicate to the Royal Society. Realizing the Society’s interest in the most up-to-date studies, Sibbald told Sloane that he had “added several accounts and the figures of some Amphibious Aquatic Animals, and of some of mixed Kinds, as the Mermaids or Syrens seen sometimes in our Seas”.5 Here were two leading thinkers of the eighteenth century exchanging erudite missives on merpeople.

On July 5, 1716, Cotton Mather also penned a letter to the Royal Society of London. This was not odd, as the Boston naturalist often detailed his scientific findings. Yet this letter’s subject was somewhat curious — titled “a Triton”, the missive demonstrated Mather’s sincere belief in the existence of merpeople. The Royal Society of London fellow began by explaining that, until recently, he considered merpeople no more real than “centaurs or sphynxes”. Mather found myriad historical accounts of merpeople, ranging from the ancient Greek Demostratus, who witnessed a “Dried Triton . . . at ye Town of Tanagra”, to Pliny the Elder’s assertions of mermaids and tritons’ existence. Yet because “Plinyisums are of no great Reputation in our Dayes”, Mather noted, he passed off much of these ancient accounts as false. Mather’s “suspicions” of the existence of such creatures “had got more Strength given”, however, when he read sundry ancient accounts via well-respected European thinkers like Boaistuau and Bellonius.6

Still, Mather was not totally convinced, at least until February 22, 1716, when “three honest and credible men, coming in a boat from Milford to Brainford (Connecticut)”, encountered a triton. Having heard this news at first hand, Mather could only exclaim, “now at last my credulity is entirely conquered, and I am compelled now to believe the existence of a triton”. As the creature fled the men, “they had a full view of him and saw his head, and face, and neck, and shoulders, and arms, and elbows, and breast, and back all of a human shape . . . [the] lower parts were those of a fish, and colored like a mackerel”. Though this “triton” escaped, it convinced Mather of merpeople’s existence. Maintaining that his story was not false, Mather promised the Royal Society that he would continue to relay “all New occurrences of Nature”.7

The famous naturalist Carl Linnaeus also threw himself into investigating mermaids and tritons. Having read newspaper articles detailing mermaid sightings in Nyköping, Sweden, Linnaeus sent a letter to the Swedish Academy of Science in 1749 urging a hunt in which to “catch this animal alive or preserved in spirits”. Linnaeus admitted, “science does not have a certain answer of if the existence of mermaids is a fact or is a fable or imagination of some ocean fish”. Yet in his mind, the reward outweighed the risk, as the discovery of such a rare phenomenon “could result in one of the biggest discoveries that the Academy could possibly achieve and for which the whole world should thank the Academy”. Perhaps these creatures could reveal humankind’s origins? For Linnaeus — world-renowned for his contributions to taxonomical classification — this ancient mystery must be solved.8

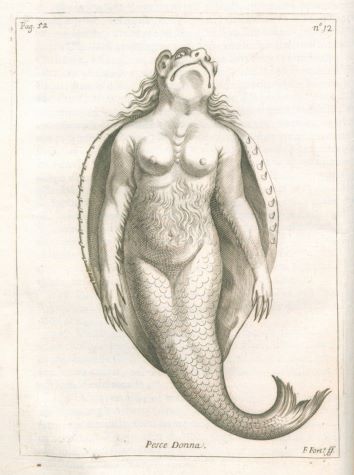

The Dutch artist Samuel Fallours also claimed to have discovered merpeople in a distant land, and in doing so set off a decades-long debate that spanned continents and media types. Fallours lived in Ambon, Indonesia, from 1706 to 1712 while serving as a clergy’s assistant for the Dutch East India Company. During Fallours’ tenure on a “Spice Island”, he drew various representations of native flora and fauna. One image happened to depict a mermaid, or “sirenne”. Fallours’ “sirenne” closely resembled the classic depiction of a mermaid, with long, sea-green hair, a pleasant face and a bare midsection that turned into a blue/green tail at the waist. This mermaid’ s skin, however, was dark (with a slight greenish tinge), implying a similarity with the local indigenous population.9

In the notes that accompanied Fallours’ original drawing, the Dutch artist contended that he “had this Syrene alive for four days in my house at Ambon in a tub of water”. Fallours’ son had brought it to him from the nearby island of Buru “where he purchased it from the blacks for two ells of cloth”. Eventually, the whimpering creature died of hunger, “not wishing to take any nourishment, neither fishes nor shell fishes, nor mosses or grasses”. After the mermaid’s death, Fallours “had the curiosity to lift its fins in front and in back and [found] it was shaped like a woman”. Fallours claimed that the specimen was subsequently relayed to Holland and lost. The story of this Ambon siren, however, had only just begun.10

Years before Louis Renard, a French-born book dealer living in Amsterdam, even published a version of Fallours’ “sirenne” in his own Poissons, ecrevisses et crabes (1719), Fallours’ images had already enjoyed wide distribution. Yet, because of the unusually bright colours and fantastic creatures represented in Fallours’ drawings, many doubted their accuracy and veracity. Renard was especially worried about the validity of Fallours’ sirenne, exclaiming, “I am even afraid the monster represented under the name of mermaid . . . needs to be rectified.”11

Philosophers found both promise and disgust in Fallours’ painting and the subsequent dialogue that Renard initiated with his letters. In his preface to the 1754 version of Renard’s Poissons, ecrevisses et crabes, the Dutch collector and director of the menageries and “Natuur-en Kunstcabinetten des Stadhouders” Aernout Vosmaer called objections to merpeople’s reality “weak”, and contended that “this monster, if we must call it by this name (although I do not see the reason for it)” was simply able to avoid humans’ traps better than any other creature (because of its hybrid nature) and was thus rarely seen. Because of merpeople’s biological similarity to humans, furthermore, Vosmaer argued that they were “more subject to decay after death than the body of other fishes”. Such a lack of preservation not only diminished sightings, it also went towards explaining the lack of full specimens in cabinets of curiosities.12

By the mid-eighteenth century, a growing number of physicians not only believed in the existence of merpeople, but also began to wonder what sort of ramifications such creatures might have for understanding humanity’s origins and future. As G. Robinson noted in The Beauties of Nature and Art Displayed in a Tour Through the World (1764), “though the generality of natural historians regard mermen and mermaids as fabulous animals . . . as far as the testimony of many writers for the reality of such creatures may be depended upon, so much reason there appears for believing their existence.” The Reverend Thomas Smith took Robinson’s contention to an even more definitive note four years later, asserting that while “there are many persons indeed who doubt the reality of mermen and mermaids . . . yet there seems to be sufficient testimony to establish it beyond dispute”. But the problem remained: men like Robinson and Smith could rely only upon ancient, often ridiculed sightings or tenuous hypotheses for their “proof”. They needed scientific research to back up their claims, and they got it.13

Two especially important articles — each approaching merpeople through unique scientific methodology — appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine between 1759 and 1775. The first piece, published in December 1759, accompanied a plate image of a “Syren, or Mermaid . . . said to have been shewn in the fair of St Germains [Paris]” in 1758. The author noted that this siren was “drawn from life . . . by the celebrated Sieur Gautier”. Jacques-Fabien Gautier, a French printer and member of the Dijon Academy, was widely recognized for his skill in printing accurate images of scientific subjects. Attaching Gautier’s name to the print garnered immediate credibility, even for such a strange image; but even without Gautier’s name attached to it, the print and its accompanying text were distinguished by their modern scientific methodology. Gautier had apparently interacted with the living creature, finding that it was “about two feet long, alive, and very active, sporting about in the vessel of water in which it was kept with great seeming delight and agility”.14

Gautier consequently recorded that “its positions, when it was at rest, was always erect. It was a female, and the features were hideously ugly”. As displayed in detail by the accompanying print, Gautier found its skin “harsh, the ears very large, and the back-parts and tail were covered with scales”. According to the image, this was not the mermaid that had long graced cathedrals throughout Europe. Nor did it match the description relayed by so many other naturalists and discoverers throughout history. Where most had seen a striking female form, distinguished by flowing blue-green hair, Gautier’s mermaid was completely bald with “very large” ears and “hideously ugly” features. Gautier’s siren was also much smaller than traditional mermaids at only sixty centimetres (two feet) tall. More than anything, Gautier’s mermaid reflected the mid-eighteenth-century approach to studying the wondrous aspects of nature: the Frenchman employed well-respected scientific techniques — in this case a close inspection of the creature’s anatomy and an accurate accompanying drawing (much resembling those of other illustrated creatures at the time) — to display as reality what many still considered fantasy.15

Scholars used the Gautier publication to reflect upon the legitimacy of merpeople. An anonymous contributor to the June 1762 issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine exclaimed that Gautier’s image “seems to establish the fact incontrovertibly, that such monsters do exist in nature”. But this author had further evidence. An April 1762 edition of the Mercure de France reported that in June the previous year two girls playing on a beach on the island of Noirmoutier (just off the southwest coast of France) “discovered, in a kind of natural grotto, an animal of a human form, leaning on its hands”. In a rather morbid turn of events, one of the girls stabbed the creature with a knife and watched as it “groaned like a human person”. The two girls then proceeded to cut off the poor creature’s hands “which had fingers and nails quite formed, with webs between the fingers”, and sought the aid of the island’s surgeon, who, upon seeing the creature, recorded:

it was as big as the largest man . . . its skin was white, resembling that of a drowned person . . . it had the breasts of a full-chested woman; a flat nose; a large mouth; the chin adorned with a kind of beard, formed of fine shells; and over the whole body, tufts of similar white shells. It had the tail of a fish, and at the extremity of it a kind of feet.

Such a story — when verified by a trained and trusted surgeon — only further proved Gautier’s research. For a growing number of eighteenth-century Britons, merpeople existed, bore a striking resemblance to humans, and needed to be studied at length.16

In May 1775 the Gentleman’s Magazine published an account of a mermaid “taken in the Gulph of Stanchio, in the Archipelago or Aegean Sea, by a merchantman trading to Natolia” in August 1774. Like Gautier’s 1759 “syren”, this specimen was drawn and described in detail. Yet the author also distanced himself from Gautier, noting that his mermaid “differs materially from that shewn at the fair of St Germaine, some years ago”. In an especially interesting turn of events, the author utilized a comparison of the two mermaid prints to speculate on issues of race and biology, contending that “there is reason to believe, that there are two distinct genera, or, more properly, two species of the same genus, the one resembling the African blacks, the other the European whites”. While Gautier’s siren “had, in every respect, the countenance of a Negro”, the author found that his mermaid displayed “the features and complexion of an European. Its face is like that of a young female; its eyes a fine light blue; its nose small and handsome; its mouth small; its lips thin”.17

Early modern English writers leaned on two stereotypes to commodify and denigrate African female bodies, as the historian Jennifer L. Morgan has shown. First, they “conventionally set the black female figure against one that was white — and thus beautiful”. Here this 1775 author follows perfectly in line, comparing Gautier’s “Negro” and “hideously ugly” mermaid to his own beautiful mermaid with the “features and complexion of an European”. Second, early modern Europeans concentrated on African women’s supposed “sexually and reproductively bound savagery” in order to ultimately turn to “black women as evidence of a cultural inferiority that ultimately became encoded as racial difference”. Not only were naturalists using the science of merpeople to gain a deeper understanding of the natural order of sea creatures, they were also utilizing their interpretations of these mysterious beings to reflect upon humans’ — especially white humans’ — place in an ever-changing racial, biological framework.18

Carl Linnaeus and his student Abraham Osterdam further complicated the narrative of classification and legitimacy. Though the Swedish Academy found nothing in their search for Linnaeus’ mermaid in 1749, Linnaeus and Osterdam took matters into their own hands by publishing a dissertation on the Siren lacertina (The Lizard Siren) in 1766. Having detailed a long list of mermaid sightings throughout history in the initial pages of this dissertation, they next relayed myriad instances of “marvelous animals and amphibians” that closely resembled creatures of lore and, consequently, made classification tricky. Ultimately, they judged this mermaid-like creature “worthy of an animal, which should be shown to those who are curious, because it is a new form”. The “father of classification” had apparently discovered a “worthy” piece of the natural puzzle, and it linked humans (even if distantly) to animals of the sea. The Siren lacertina also, importantly, further blurred the lines of classification that Linnaeus had so proudly developed, suggesting that perhaps human beings might find some distant relation to amphibious creatures.19

Eighteenth-century philosophers’ investigations of merpeople represented both the endurance of wonder and the emergence of rational science during the Enlightenment period. Once resting at the core of myth and on the very fringes of scientific research, now mermaids and tritons were steadily catching philosophers’ attention. Initially such research was relegated to newspaper articles, brief mentions in travellers’ narratives, or hearsay, but by the second half of the eighteenth century, naturalists began to approach merpeople with modern scientific methodology, dissecting, preserving and drawing these mysterious creatures with the utmost rigour. By the close of the eighteenth century, mermaids and tritons emerged as some of the most useful specimens for understanding humanity’s marine origins. The possibility (or, for some, reality) of merpeople’s existence forced many philosophers to reconsider previous classification measures, racial parameters, and even evolutionary models. As more European thinkers believed — or at least entertained the possibility — that “such monsters do exist in nature”, Enlightenment philosophers merged the wondrous and rational to understand the natural world and humanity’s place in it.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Pennsylvania Gazette, May 6, 1736; Providence Gazette, July 15, 1769. For examples from English newspapers, see St. James Evening Post, January 31 – February 3, 1747; Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer, September 7, 1717.

- In Dr Samuel Johnson’s opinion, newspapers were “enlightening” outlets that destroyed “barbarous” ignorance through the “diffusion” of knowledge. James Boswell, Boswell’s Life of Johnson (London: Bigelow, Brown & Co., 1904), 452.

- Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750 (New York: Zone Books, 2001), 1–11. As Richard Carrington noted, “the eighteenth century, which prided itself on its worldliness, cynicism, and good sense, was nevertheless as passionately addicted to mermaids as the preceding age”. Richard Carrington, Mermaids and Mastodons: A Book of Natural and Unnatural History (New York: Rinehart, 1957), 10.

- Though Enlightenment thinkers considered themselves arbiters of a “new science [with an] objective approach to the study of nature”, wonder, mystery, and superstitions remained central to their investigations of humanity and the natural world. See Daston and Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature, 20; Barbara M. Benedict, Curiosity: A Cultural History of Early Modern Inquiry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 2; Joy Kenseth, “The Age of the Marvelous: An Introduction”, in The Age of the Marvelous, ed. Joy Kenseth (Hanover: Hood Museum of Art, 1991), 54; Bob Bushaway, “‘Tacit, Unsuspected, but Still Implicit Faith’: Alternative Belief in Nineteenth-century Rural England”, in Popular Culture in England, c. 1500–1850, ed. Tim Harris (New York: Springer, 1995), 189.

- “Sir Robert Sibbald to Sir Hans Sloane, November 29, 1703 (Edinburgh)”, Sloane ms 4039, ff. 218–19, British Library, London.

- “Cotton Mather to the Royal Society, July 5, 1716”, Cotton Mather Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston, MA). I avoid using the term “scientist” to describe early modern gentlemen in this work, as it is an anachronistic term denoting a professionalization that simply did not exist at the time. Instead, I rely upon the term “naturalist” (in Aristotle’s sense of the term, which denoted one who systematically studied nature, natural history, natural philosophy, astronomy, optics, and medicine) or, simply, “philosopher”.

- “Cotton Mather to the Royal Society, July 5, 1716”.

- “Carl Linnaeus to Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademien, August 29, 1749”, The Linnaean Correspondence, http://linnaeus.c18.net, January 24, 2019. Special thanks to Lina Waara for translation assistance. Sylvanus Urban reported in his Gentleman’s Magazine in 1749, “At Nykoping, in Jutland, was lately caught a mermaid, which from the waist upward had a human form, but the rest was like a fish, with a tail turning up behind, the fingers were joined together by a membrane; it struggled, and beat itself to death in the net”. Sylvanus Urban, Gentleman’s Magazine, and Historical Chronicle for 1749 (London, 1749), vol. xix, 428.

- The early eighteenth-century philosopher Benoît de Maillet similarly noted that a merman seen in the Nile in the sixth century had “Skin of a Brownish Colour”. Benoît de Maillet, Telliamed; or, Conversations between an Indian Philosopher and a French Missionary on the Diminution of the Sea, trans. and ed. Albert V. Carozzi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1968), 192.

- Pietsch, 6–7.

- Louis Renard, Poissons, ecrevisses et crabes, 2nd edn (Amsterdam: Reincier & Josué, 1754); Pietsch, “Samuel Fallours and his ‘Sirenne’”, 10.

- The Beauties of Nature and Art Displayed in a Tour Through the World (London: G. Robinson, 1764), 58; Thomas Smith, The Wonders of Nature and Art, Being an Account of Whatever is Most Curious and Remarkable Throughout the World, 2nd edn (London: Carnan and Newbery, 1768), vol. 11, 197.

- Sylvanus Urban, Gentleman’s Magazine for December 1759 (London, 1759), vol. xxix, 590.

- Urban, 590.

- Sylvanus Urban, Gentleman’s Magazine for June 1762 (London, 1762), vol. xxxii, 253.

- Sylvanus Urban, Gentleman’s Magazine for May 1775 (London, 1775), vol. xlv, 216–17.

- Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 14, 49, 30–50.

- Carl Linnaeus and Abraham Osterdam, Sirenlacertina, dissertatione academica orbi erudito data (Uppsala, 1766); Margaret Jean Anderson, Carl Linnaeus: Father of Classification (Springfield: Enslow, 1997); Thomas Bartholin, “Of the Mermaid, &c.” in the Miscellanea naturae curiosorum, Dec. 1, 1671”, 118–21; Richard Wahlgren, “Carl Linnaeus and the Amphibia”, Bibliotheca herpetological 9 (2011): 5–37; Carina Nynäs and Lars Bergquist, A Linnaean Kaleidoscope: Linnaeus and his 186 Dissertations, vol. 11 (Stockholm: The Hagstrïmer Medico-Historical Library, 2016), 439–43. The “siren lacertina” still inhabits the southeastern portion of North America as one of America’s largest amphibians. See also Philip Hayward, Making a Splash: Mermaids (and Mermen) in 20th and 21st Century Audiovisual Media (Bloomington: John Libbey, 2017), 169.

Public Domain Works

- Poissons, ecrevisses et crabes, Louis Renard (1754)

- Letter to Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakadamien, Carl Linnaeus (1749)

- “On Mermaids”, The Gentleman’s Magazine (1823)

- The Gentleman’s Magazine (1775)

- The Gentleman’s Magazine, and Historical Chronicle (1749)

Further Reading

- The Penguin Book of Mermaids, edited by Cristina Bacchilega

- Curiosity: A Cultural History of Early Modern Inquiry, by Barbara M. Benedict

- Merpeople: A Human History, by Vaughn Scribner