Examining the archaeology of slavery in the Caribbean sugar plantations.

Sugar and Slavery

The introduction of sugar cultivation to St Kitts in the 1640s and its subsequent rapid growth led to the development of the plantation economy which depended on the labour of imported enslaved Africans. African slaves became increasingly sought after to work in the unpleasant conditions of heat and humidity. European planters thought Africans would be more suited to the conditions than their own countrymen, as the climate resembled that the climate of their homeland in West Africa. Enslaved Africans were also much less expensive to maintain than indentured European servants or paid wage labourers.

The main reason for importing enslaved Africans was economic. In 1650 an African slave could be bought for as little as £7 although the price rose so that by 1690 a slave cost £17-22, and a century later between £40 and £50. In comparison, in the 17th century a white indentured labourer or servant would cost a planter £10 for only a few years’ work but would cost the same in food, shelter and clothing. Consequently, after 1660 very few new white servants reached St Kitts or Nevis; the Black enslaved Africans had taken their place.

As a consequence of these events, the size of the Black population in the Caribbean rose dramatically in the latter part of the 17th century. In the 1650s when sugar started to take over from tobacco as the main cash crop on Nevis, enslaved Africans formed only 20% of the population. By the census of 1678 the Black population had risen to 3849 against a white population of 3521. By the early 18th century when sugar production was fully established nearly 80% of the population was Black. The great increase in the Black population was feared by the white plantation owners and as a result treatment often became harsher as they felt a growing need to control a larger but discontented and potentially rebellious workforce.

Enslaved Africans were often treated harshly. First they had to survive the appalling conditions on the voyage from West Africa, known as the Middle Passage. The death rate was high. One recent estimate is that 12% of all Africans transported on British ships between 1701 and 1807 died en route to the West Indies and North America; others put the figure as high as 25%. Nearly 350,000 Africans were transported to the Leeward Islands by 1810, but many died on the voyage through disease or ill treatment; some were driven by despair to commit suicide by jumping into the sea.

Once they arrived in the Caribbean islands, the Africans were prepared for sale. They were washed and their skin was oiled. Finally they were sold to local buyers. Often parents were separated from children, and husbands from wives.

The plantation relied almost solely on an imported enslaved workforce, and became an agricultural factory concentrating on one profitable crop for sale. Enslaved Africans were forced to engage in a variety of laborious activities, all of them back-breaking. The work in the fields was gruelling, with long hours spent in the hot sun, supervised by overseers who were quick to use the whip. Tasks ranged from clearing land, planting cane, and harvesting canes by hand, to manuring and weeding. The plantation relied on an imported enslaved workforce, rather than family labour, and became an agricultural factory concentrating on one profitable crop for sale.

Inside the plantation works, the conditions were often worse, especially the heat of the boiling house. Additionally, the hours were long, especially at harvest time. The death rate on the plantations was high, a result of overwork, poor nutrition and work conditions, brutality and disease. Many plantation owners preferred to import new slaves rather than providing the means and conditions for the survival of their existing slaves. Until the Amelioration Act was passed in 1798, which forced planters to improve conditions for enslaved workers, many owners simply replaced the casualties by importing more slaves from West Africa.

Diet and Food Production for Enslaved Africans

Overview

From the 17th century onwards, it became customary for plantation owners to give enslaved Africans Sundays off, even though many were not Christian. Enslaved Africans used some of this free time to cultivate garden plots close to their houses, as well as in nearby ‘provision grounds’.

Provision grounds were areas of land often of poor quality, mountainous or stony, and often at some distance from the villages which plantation owners set aside for the enslaved Africans to grow their own food, such as sweet potatoes, yams and plantains. In addition to using the produce to supplement their own diet, slaves sold or exchanged it, as well as livestock such as chickens or pigs, in local markets. The location of the provision grounds at the Jessups estate, one of the Nevis plantations studied by the St Kitts-Nevis Digital Archaeology Initiative, is shown on a 1755 plan of the plantation. It is labelled as the ‘Negro Ground’ attached to Jessups plantation, high up the mountain.

By the early 18th century enslaved Africans trading in their own produce dominated the market on Nevis. In William Smith’s day, the market in Charlestown was held from sunrise to 9am on Sunday mornings where “the Negroes bring Fowls, Indian Corn, Yams, Garden-stuff of all sorts, etc”.

In Charlestown today there is a place now known as the ‘Slave Market’. We do not know whether this was the place where enslaved Africans were sold on arriving in Nevis or whether it is where slaves used to sell their produce on Sundays.

The location of the provision grounds at the Jessup’s estate, one of the Nevis plantations studied by the St Kitts-Nevis Digital Archaeology Initiative, is shown on a 1755 plan of the plantation. It is labelled as the ‘Negro Ground’ attached to Jessup’s plantation, high up the mountain.

Food Supplies

Although the volcanic soils of the two islands were highly fertile, plantation owners and managers were so eager to maximise profits from sugar that they preferred to import food from North America rather than lose cane land by growing food. Salted meat and fish, along with building timber and animals to drive the mills, were shipped from New England.

The plantation owners provided their enslaved Africans with weekly rations of salt herrings or mackerel, sweet potatoes, and maize, and sometimes salted West Indian turtle. The enslaved Africans supplemented their diet with other kinds of wild food. Revd Smith observed,

“I have known some of them to be fond of eating grasshoppers, or locusts; others will wrap up cane rats, in bonano [banana] leaves, and roast them in wood embers”.

On the Stapleton estate on Nevis records show that there were 31 acres set aside for the estate to grow yams and sweet potatoes while slaves on the plantation had five acres of provision ground, probably on the rougher area of the plantation at higher elevations, where they could grow vegetables and poultry. The plantation owner distributed to his slaves North American corn, salted herrings and beef, while horse beans and biscuit bread were sent from England on occasion.

Although the enslaved Africans were permitted provision grounds and gardens in the villages to grow food, these were not enough to stop them suffering from starvation in times of poor harvests. A law was passed in Nevis in 1682 to force plantation owners to provide land for food crops to prevent starving slaves from stealing food. In the year 1706 there was a severe drought which caused most food crops to fail. Many slaves would have died from starvation had not a prickly type of edible cucumber grown that year in great profusion.

In 1750 St Kitts grew most of its own food but 25 years later and Nevis and St Kitts had come to rely heavily on food supplies imported from North America. At the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1776 trade was closed between North America and the British islands in the West Indies, leading to disastrous food shortages. In 1777 as many as 400 slaves died from starvation or diseases caused by malnutrition on St Kitts and on Nevis.

Slave Villages

St. Kitts

Slave villages represent an important but little-known part of the Caribbean landscape. Since abandonment, their locations have been forgotten and in many cases leave no trace above ground. As they are virtually invisible on the landscape today, village locations are particularly liable to destruction or development, unlike the more substantial stone constructed houses of the European plantation owners. However, they are integral in creating a direct link between past and present because villages represent the homes of the ancestors of many modern people in the islands today.

St Kitts is probably the only island in the West Indies that has a map showing the location of all the slave villages. William McMahon’s map drawn in 1828 records shows the landscape of plantation estates shortly before emancipation, after nearly three centuries of development.

A team of British archaeologists studied the slave villages in two areas of St Kitts in 2004 and 2005, using the detailed McMahon map to locate the sites. The team, Jon Brett and Rob Philpott, with colleagues Lorraine Darton and Eleanor Leech, surveyed a number of sugar plantations in the parishes of St Mary Cayon and Christ Church Nichola Town.

They found that the locations of slave villages shared some common features. They were usually close enough to the main house and plantation works that they could be seen from the house. This allowed the owner or manager to keep an eye on his enslaved workforce, while also reinforcing the inferior social status of the enslaved.

The villages were located carefully with respect to the plantation works and main house. On the St Kitts plantations, the slave villages were usually located downwind of the main house from the prevailing north-easterly wind. In the mid-18th century Reverend William Smith described a similar scene when characterising the location of the slave villages on Nevis;

“They live in Huts, on the Western Side of our Dwelling-Houses, so that every Plantation resembles a small Town”. The location meant that “we breathe the pure Eastern Air, without being offended with the least nauseous smell: Our Kitchens and Boyling-houses are on the same side, and for the same reason”.

In 1724 Father Labat drew his idealised design for an estate layout based on his 12 years’ experience of managing an estate on the French island of Martinique. His design shows one or two rows of slave houses set downwind of the estate house. They are close to the animal enclosures, so the labourers could keep watch over the livestock, and set below the plantation house which stands on a small hill.

In the St Kitts plantations, the slave villages were usually located downwind of the main house from the prevailing north-easterly wind. Villages were often located on the edge of the estate lands or in places that were difficult to cultivate such as areas near the edge of the deep guts or gullies. Placing them in these locations ensured that they did not take up valuable cane-growing land. At the Hermitage the slave village stood beside the high sea-cliff, and was marked by a boundary bank, which perhaps originally supported a fence or hedge. Others lay in the base of valleys, such as The Spring, beside a much steeper gut or gully, where access for laden carts of sugar cane was difficult.

We found no architectural trace however of the houses at any of the slave villages. Not surprisingly, the remains of wooden huts, with thatched roofs, would in any case leave few traces on the surface. However, possible platforms where houses may have stood have been observed at Ottley’s and the Hermitage within the areas shown on the McMahon map as slave villages in 1828.

After emancipation, many newly freed labourers moved away from the plantations, emigrating or setting up new homes as squatters on abandoned estate land. The movement of emancipated slave populations and establishment of new villages away from the old plantation lands suggest that some slave villages were abandoned soon after emancipation; others may have remained in use for the labourers who chose to stay on the plantation as paid workers and rented their house and land.

The first village for newly free labourers, Challenger’s on St Kitts, was set up in 1840 when a customs officer John Challenger sold or rented small lots out of a tract of land to newly free labourers. Other villages were established on steep unused land, often in the deep guts, which were unsuitable for cultivation, such as Ottley’s or Lodge villages in St Kitts.

Nevis and Elsewhere in the Caribbean

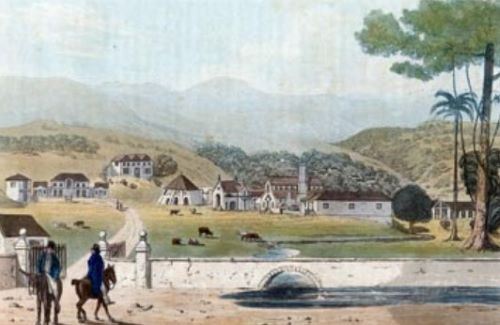

Historic illustrations of plantations in the Caribbean occasionally show slave villages as part of a wider landscape setting, though they are often romanticised views, rather than realistic depictions.

For the most part the layout of slave villages was not rigidly organised, as they grew up over time and the inhabitants had some choice about the location of their houses. The plan of the 18th century slave village at Jessups is a good example of this kind of layout. The British planter Bryan Edwards observed that in Jamaica slave “cottages” were;

“…seldom placed with much regard to order, but, being always intermingled with fruit-trees, particularly the banana, the avocado-pear, and the orange (the Negroes’ own planting and property) they sometimes exhibit a pleasing and picturesque appearance.”

By the late 18th century, some plantation owners laid out slave villages in neat orderly rows, as we can see from estate maps and contemporary views. John Pinney (1740-1818) who owned the plantation of Mountravers on Nevis gives two reasons for this layout. In the 1790s Pinney instructed that the houses in the slave village should be;

“…built at approximate distances in right lines to prevent accidents from fire and to afford each negro a proper piece of land around the house”.

He also planted coconut and breadfruit trees for his enslaved labourers (Pares 1950, 127).

Contemporary illustrations show that slave villages were often wooded. In 1820-21 James Hakewill drew a number of sugar plantations in Jamaica showing the slave villages in several cases set within wooded areas, which served not only as shade but also as fruit trees to provide food for the enslaved populations.

Slave Houses

St. Kitts and Nevis

No slave houses survive in St Kitts and Nevis, and very few in the Americas as a whole. The houses of the enslaved Africans were far less durable than the stone and timber buildings of European plantation owners. Therefore documents provide our two main sources of information on slave houses. The first type consists of accounts from travel writers or former residents of the West Indies from the 17th and 18th centuries who describe slave houses that they saw in the Caribbean; the second are contemporary illustrations of slave housing. In recent years, a third source of information, archaeology, has begun to contribute to our understanding.

Slave houses in Nevis were described as ‘composed of posts in the ground, thatched around the sides and upon the roof, with boarded partitions’. They were little more than huts, with a single storey and thatched with cane trash. In the inventory of property lost in the French raid on St Kitts in February 1706 they were generally valued at as little as £2 each.

Few illustrations survive of slave villages in St Kitts and Nevis. A series of watercolour paintings by Lieutenant Lees, dated to the 1780s are one exception. His paintings mainly depict the British fort on Brimstone Hill, but also show groups of slave houses. One painting illustrates a slave village near the foot of Brimstone Hill. The eighteen visible huts of the village are arranged in no particular order within a stone-walled enclosure, which is surrounded by cane fields on three sides. The houses have hipped roofs, thickly thatched with cane trash. A striking feature of the village area is the dense mass of bushes and trees, including coconut palms. Another slave village stands beside a fenced compound, connected with the fort. However, as this village may have been associated with the garrison of the fort it may not have been typical of villages at sugar plantations.

The estate map of Clarke’s estate in Nevis, dated early 19th century, shows a slave village on a strip of land between a road on one side and a steep ravine on the other. The village contains eighteen small huts, each with the door in the narrow end, set at roughly equal distances, some with ridged garden plots beside them.

The slave houses of the 18th century show a close resemblance to the late 19th century wooden houses with thatched roofs that appear in the earliest photographs of rural houses in St Kitts.

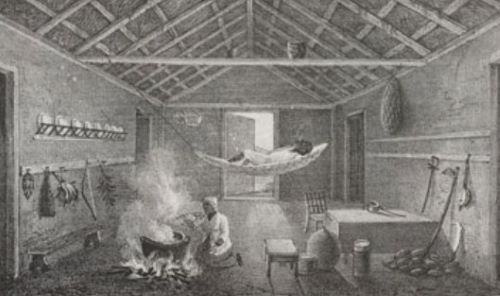

While the historic pictures provide us with some useful information, they tell us little of the people who inhabited the houses, the furniture and fittings in the interior, and the materials from which they were built. For details such as these we have to turn to written records from other islands and to the evidence of archaeology.

Elsewhere in the Caribbean

Contemporary pictures of slave villages drawn by visitors or residents in the Caribbean show that slave houses often consisted of small rectangular huts. Several descriptions survive from the island of Barbados. The German noble Heinrich von Uchteritz who was captured in battle in England and sold to a planter in Barbados in 1652 described houses of the enslaved Africans on the island. They were no more than small cabins or huts, “none above six foot square” and “built of inferior wood, almost like dog huts, and covered with leaves from trees which they call plantain, which is very broad and almost shelf-like and serves very well against rain”. At that time the Black slaves did not sleep in hammocks but on boards laid on the dirt floor. They had their own gardens in which they grew yams, maize and other food, and were allowed to keep chickens to provide eggs for their children. Their houses were little different from those of the white servants at the time.

Slave houses in Barbados have been described as;

“…consisting most frequently of wattle or stick huts, which were roofed with palm thatch. Furnishings within were always sparse and crude, most occupants sleeping in hammocks, or on the earth floor.”

Another description of houses paints a similar picture;

“the architecture… is so rudimentary as it is simple. A roof of plantain-leaves with a few rough boards, nailed to the coarse pillars which support it, form the whole building.”

Huts like this needed constant maintenance and frequent replacement.

Conditions for enslaved Africans changed for the better from the late 18th century onwards. The Amelioration Act of 1798 improved conditions for slaves, forcing plantation owners to provide clothes, food, medical treatment and basic education, as well as prohibiting severe and cruel punishment. Slaves were also not allowed to work more than 14 hours a day. In part the Act was a response to the increasingly powerful arguments of abolitionists. However, it was also in the planters’ own interests to avoid slave rebellions as well as to avoid the need to transport fresh slaves from Africa by increasing the birth rate amongst the existing enslaved population through better living standards. As a result housing for the enslaved workers was improved towards the end of the 18th century. In Barbados for example, the houses on some plantations were upgraded to wooden cabins covered with shingles (thin wooden tiles) and placed in a common yard to encourage family relations to develop. In Jamaica too some planters improved slave housing at this time, reorganising the villages into regularly planned layouts, and building stone or shingled houses for their workforce.

A picture published in 1820 by John Augustine Waller, shows slave huts on Barbados. They are small low rectangular, one room structures, under roofs thatched with leaves. One hut is cut away to reveal the inside. It shows the enslaved couple with their sparse belongings. They have a pair of drinking glasses and a bottle on the table. A hat hangs on the wall, a group of large pots stands on a shelf and there is a small bed in the corner.

By the late 18th century Bryan Edwards drew on his own experience as a British planter in Jamaica to describe ‘cottages’ of the enslaved workforce. As Edwards was a staunch supporter of the slave trade, his descriptions of the slave houses and villages present a somewhat rosy picture. The houses measured 15 to 20 feet long and had two rooms. They were built with posts driven into the ground, wattle and daub walls, and rooms thatched with palm leaves. The floors were of beaten earth and a fire was lit at night in the middle of one room. He describes the possessions of the enslaved couple;

“…of furniture they have not great matters to boast, nor, considering their habits of life, is much required. The bedstead is a platform of boards, and the bed a mat covered with a blanket; a small table; two or three low stools; an earthen jar for holding water; a few smaller ones; a pail; an iron pot; calabashes [hollowed out gourds] of different sizes (serving very tolerably for plates, dishes and bowls) make up the rest”.

Enslaved domestic workers or craftsmen had larger houses, with boarded floors, and;

“…a few have even good beds, linen sheets, and musquito nets, and display a shelf or two of plates and dishes of Queen’s or Staffordshire ware.”

Enslaved workers who lived and worked close to the owner’s household were in the position to receive rewards or gifts of money or other items. John Pinney on Nevis gave his boilers check shirts if the sugar was good, while enslaved women who gave birth were presented with baby linen (Pares 1950, 132). The enslaved labourers could also purchase goods in the market place, through the sale of livestock, produce from their provision grounds or gardens, or craft items they had manufactured.

Archaeology is often the only way to recover detailed information on the possessions of the enslaved workers, since the items were rarely recorded in documents. Archaeology can reveal their tools and domestic vessels and utensils, such as ceramic pots. It can also provide insight into their leisure activities, such as smoking and gaming represented by clay tobacco pipes or marbles. Finally it can also provide information on their dress and fashions, through the recovery and analysis of items such as dress fittings, buttons and beads.

Originally published by National Museums Liverpool to the public domain.