Examining demons and monstrous creatures of ancient Mesopotamia.

By Dr. Gina Konstantopoulos

Assistant Professor in Assyriology and Cuneiform Studies

University of California Los Angeles

Abstract

Demons and monsters are inherently moveable creatures: from the late second millennium BCE onwards a number of demons and monsters migrate from their native Mesopotamian contexts, moving westward. Of course, these figures do not remain static throughout their journey, instead acquiring the characteristics of the different cultural contexts wherein they are now found. This paper considers the different representations of several of these demonic figures within the context of the Levant, analyzing their artistic representations as well as the more diffuse textual evidence for them. As the line between demonic and divine was already thin and mutable in Mesopotamia, we see a similar flexibility to their definitions when these figures move into their new contexts. As deities are, generally speaking, less marginal beings than demons, the deities that do move westward, or are employed in the west in Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian sources, do so because they are already demonstrate a more flexible character and wider possible applicability and use. This principle is especially seen in the attestations of one such figure, a group of seven divine-demonic beings known as the Sebettu, who are employed with particular focus in Neo-Assyrian references connected to the western frontier.

Introduction

This article considers how religion was manifested and utilized on the edges of empire in the Middle and Neo-Assyrian periods in Mesopotamia. In particular, it focuses on how the figures of monsters and demons moved about these same edges. In some instances, they naturally travelled from location to location, traversing boundaries, both geographic and cultural. These figures may change as they move, but they retain a degree of inherent consistency in their depictions, despite their adaptations. In other instances, these figures are subject to more direct manipulation, deliberately invoked in royal inscriptions to paint a picture of the power and standing of the king. This less organic movement is matched by a more stable depiction of their characteristics.

In tackling these themes, this study will first present a brief overview of some of the theories that more broadly underscore the conception of monsters and demons, to highlight how that same methodology may apply to the monstrous creatures of Mesopotamia. Following this are two case studies of “monsters on the move.” The first is a brief investigation of the peregrinations of the monstrous figures of Humbaba, the guardian of the Cedar Forest best known from the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, and Pazuzu, the demon who was used to ward off the demoness Lamashtu in the first millennium BCE. The second case study presents a brief overview of some of the ways in which the liminal qualities of a group of demonic figures known as the Sebettu could be employed in a martial context, as a group of far-ranging warriors bound to the service of the Assyrian king. This second example is a more deliberate instance of “wandering monsters” than the first, but both represent useful models to consider.

Monsters on the Move

Both monsters and demons function as reflective expressions of culture and society. Despite being thus contextually dependent, certain methodological tools and frameworks facilitate their consideration as more universal expressions of the liminal and the Other, regardless of different cultural and historical contexts. As an initial caveat, using such methods does inevitably imply a degree of both simplification and contradiction. A number of different scholarly approaches to creating and defining demonic or monstrous beings within Mesopotamian contexts alone already exist, and even the terms “demon” and “monster” are not without their problems.1 Such imperfect terms are a compromise that allows one to circumvent repeated and lengthy considerations on the problems of terminology before being able to move into further discussion.2

One such tool may be found in a set of seven “monster theses” outlined in a similarly titled article by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (1996). Each thesis describes an essential aspect of monstrous beings that may be used to define them within a variety of contexts. Of the seven, three are most useful for a discussion of Mesopotamian monsters: that the monster possesses a body that is inherently a cultural construction; that it dwells “at the Gates of Difference”; and that it represents, even when feared, an object of both fascination and desire.3 If we consider these three points together, they construct the basic idea that monsters embody culturally intrinsic concepts or ideals; articulate the differences seen within one culture or between other cultures when compared to one another; and are inherently compelling because they represent both the foreign and the forbidden (Cohen 1996, 4, 7–12, 17–20).

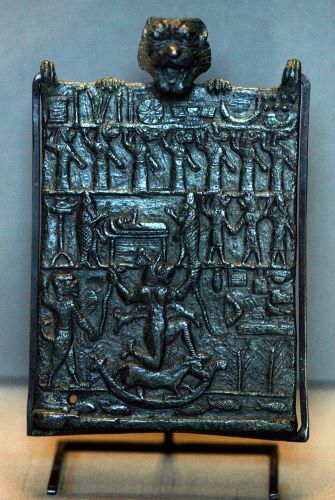

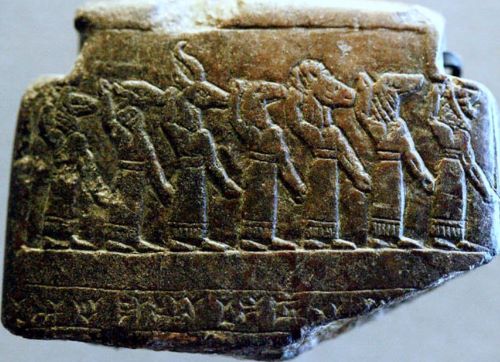

Such theses speak to the ability of monsters to operate as a distillation of core, often cultural, concepts, to the point where such qualities become inextricably associated with the monstrous or demonic figure themselves. This can be observed in some of the more prominent Mesopotamian demonic and monstrous figures, such as Humbaba, the monstrous guardian of the Cedar Forest from the Gilgamesh texts, and Pazuzu, who provides a sort of demonic protection against the demoness Lamashtu’s baby-killing ways. In both instances, the power of the figure is localized in its gaze. In the case of Pazuzu, this meant that amulets of the figure could be reduced down to his gaze alone, or at least the vector of it, resulting in the widespread distribution of Pazuzu-head amulets, clearly meant to be worn by individuals, often with the demon’s snarling visage and forward-facing eyes positioned directly outwards from the bearer.4 Humbaba, in turn, has references to his gaze rooted in both text and art, with the latter forming a large part of his representations: though he may appear in full-figure on reliefs and cylinder seals, plaques of his head, vigilant gaze prominently displayed, are also found, particularly in apotropaic contexts.5 Such qualities – here, the gaze and the protection it confers – may become so strongly representative of the figure that they alone can be used to represent the figure as a whole.

If we examine the phenomenon of traveling monsters and demons, then, it need not always be the entire monster that travels, but rather only its most representative and salient aspect or quality. A similar principle underlies the connections and thematic influences found between Mesopotamia and the ancient Mediterranean, as seen in textual examples: the entire text may not travel, but distinct imagery, wordplay, and other key features certainly do.6 Artistic representations of demons and monsters, similarly, highlight their most emblematic qualities, and these qualities may then move, influencing other monstrous figures.7

In the case of Pazuzu and Humbaba, they move west. They may appear directly as themselves in Levantine, Egyptian, and Greek contexts or influence depictions of other monsters. Regarding he former, I would point to the example of a statuette of Pazuzu now in the Ashmolean Museum. The eighth-century object is likely from the site of Tanis in Egypt and retains the core features of the demon but is personalized with an Aramaic inscription (DeGrado and Richey 2019). Pazuzu has moved west – and south – but maintains its core iconographic elements, most of which are closely tied to the figure’s power. The inscription, then, is one way in which the figure may be adapted to its new context. When we consider the latter category of movement-by-influence, we see that Pazuzu and Humbaba impose their most characteristic tropes upon other beings that belong to their new environment.8 This latter category is populated by a number of figures, none so distinct as that of Medusa and other Gorgons, which utilize that same gaze apotropaically.9

The most significant – and, moreover, the most useful – aspects of each monstrous figure may come to represent the entire figure, and invoking, or transposing, that one aspect allows for the metonymic invocation of the whole. While these singular representative qualities thus have their own attached symbolic baggage, the distillation of an entire monstrous being along the lines of its most distinctive traits, and thus into smaller and more contained elements, eases its travel, particularly across cultural and historical lines. Monsters and demons can, and do, travel, but the frequency and speed with which this movement occurs has its own spectrum of greater or lesser ease. The same general principle may be applied to the Sebettu and their use: though they are marvelously complicated figures, they are also capable of being distilled to several salient and easily transmitted points. Their warrior nature numbers, for the Assyrian kings, among their must useful traits, but this single quality is still emblematic of their messy and complicated whole. Moreover, these traits are attached to other key aspects of the Sebettu, including their inherently liminal nature as demons and their astral identity as the Pleiades, both of which position them at home on the margins.10

Demons on the March: The Sebettu

The group of seven warrior figures known as the Sebettu, or the dimin-bi, as they were most often represented in texts, navigate an identity both demonic and divine. While they never lost their demonic qualities or connotations, their divine identity allowed them to be referenced in royal inscriptions. They were increasingly utilized in texts concerned with controlling the periphery, especially its far western edges, during the Middle and Neo-Assyrian periods. Just like Pazuzu and Humbaba, the Sebettu were most often found on the margins – and again, just as with the previously discussed figures, their effectiveness in such a position rested on both their innate martial qualities and their inherent, underlying, and longstanding demonic nature. Thanks to the smaller number of references to them, the Sebettu are among those figures who may be more easily tracked, though they are far from the only examples of such a targeted political manipulation.

The kings of the Middle and Neo-Assyrian periods possessed a wide array of tools that could be employed in their attempts at maintaining and ultimately increasing the territories under their control. These ranged from directly applicable and concrete aspects of control, such as military forces, to more subtle instruments, such as political and religious propaganda that worked to serve and bolster the image of the king and thus help cement his power and control.11 In the case of the Assyrian propaganda machine, the gods themselves became tools, invoked to help support and stabilize Assyria by demonstrating its supremacy, particularly when on military campaigns to help quell rebellions in distant regions or acquire new ones. It is this model of use wherein the Sebettu find themselves, and this greater distance from the Assyrian core could facilitate a more flexible expression of particular deities. Such figures often found themselves in the company of local deities, for example, the latter of which could also be in various stages of being incorporated into the broader Assyrian pantheon, either in their own right or through their syncretism with another deity.12

The Sebettu’s role on the margins, and in the west in particular, is rooted in their dual nature as divine and demonic beings; this duality is in turn a consequence of some two thousand years of attestations across a wide range of different textual attestations and iconographic representations.13 Because the Sebettu could lay claim to this long-standing demonic heritage, they were able to access qualities most closely associated with demonic beings, which included both liminal and far-ranging geographic habits and a fearsome bearing and aspect. Demons and monsters in Mesopotamia were already and inherently predisposed to being useful at the margins, and thus move in liminal spaces and contexts. For the Sebettu, the expansionistic nature of the Middle and Neo-Assyrian rulers proved a perfect testing ground for those abilities to be put to use.

First Mentions in Assyria

The Sebettu first appear within the corpus of Assyrian royal inscriptions during the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I (1243–1207 BCE). Though the inscriptions of his predecessor, Shalmaneser I, do not reference the Sebettu, they do provide hints as to the utilization of the Assyrian pantheon in the periphery. Although the ruler continues to rely upon the sanction of the god Aššur to legitimize his actions and rule,14 he also focuses on temples located in peripheral regions, making a point to describe his restoration of the temple of Ištar in the city of Talmuššu, for example.15 Such focused attention was not without cause, as the king faced a number of foreign threats from the west, particularly the land of Hanigalbat, and centered his military efforts in that direction as a result.16 Tukulti-Ninurta I’s reference to the Sebettu centers on activity closer to home, as the inscription recounts the king’s dedication of a temple to the Sebettu in his new capital of Kār-Tukulti-Ninurta shortly after his successful siege and sack of Babylon in 1222 BCE, with the temple listed alongside those dedicated to other deities.17

When the Sebettu next appear, it is in the inscriptions of Aššur-bēl-kala (1073–1056 BCE) and with a direct association with the west. The king, who was responsible for reviving Assyria’s strength after conflict with the Arameans, recorded his exploits, mostly military campaigns, in over a dozen inscriptions, and the text that concerns the Sebettu numbers among these. Inscribed on the back of a stone female torso excavated from Nineveh, the text opens with a standard four lines detailing Aššur-bēl-kala’s position as king of Assyria and the entire world.18 It ends with the line: “The one who removes my inscriptions and my name, the Sebettu, the gods of the West (dSebettu(imin.bi) dingir.meš kurmar-tu) will attack him on the battlefield.”19 Such a reference marks the Sebettu as foreign, associated in particular with a region with which the king was in direct conflict. The admonition that they will strike down one who removes the king’s name places the Sebettu in a role identical to the potentially vengeful deities in curse sections of treaties. However, their position also situates them under the dominion of the king, and extends his own geographic sphere of influence at the same time.

Foreign Gods and Western Use

The kings directly following Aššur-bēl-kala’s reign left less in the way of inscriptions and records. As such, we have little evidence for how they might have employed the core pantheon of deities in their reigns, let alone the roles more peripheral or liminal deities, such as the Sebettu, may have taken. When the Sebettu do once again appear, it is in the context of temple construction. Aššurnaṣirpal II (810–783 BCE) twice references the construction, or rather restoration, of temples to the Sebettu.20 The ruler does not, however, invoke the support of the deities in any other context. Following this, we see the use of the Sebettu in royal inscriptions truly expand. Given the number of these attestations, I will focus herein on a selected few.21

Several examples from the Neo-Assyrian period clearly demonstrate a connection between the Sebettu and peripheral territories. Shalmaneser III (858–824 BCE) only refers to the Sebettu in one of his inscriptions, on a stone altar dedicated to the Seven found at Nineveh, but the text describes them in some detail. Its opening lines focus on qualities that would be useful to them while on campaign, citing their ability to move through the mountains and survey the heavens and earth, with the text’s closing lines centered on the Seven’s martial qualities.22

After Shalmaneser, the Sebettu appear in a treaty text between the Assyrian king Aššur-nerari V (754–745 BCE), and Mati’ilu, the ruler of Arpad, located in the vicinity of present-day Syria. They appear near the likely end of the list of gods found at the text’s conclusion, arguably positioned to take advantage of their associations with the western periphery (Parpola and Watanabe 1988). The list of divine witnesses is fronted by the god Aššur and a number of divine pairs, all attested members of the Assyrian pantheon.23 After this, the text cites deities such as Ištar of Nineveh and Arbela; deities of Kurbail and Aleppo; and then presents the Sebettu. Following the Seven, entirely foreign deities appear.24 In this manner, the treaty text incorporates smaller, more locally oriented deities, particularly those of importance to the western territories with which it is concerned, and the Sebettu serve as, depending on one’s point of view, either a transition to or a barrier between the gods closely associated with Assyria and those belonging to foreign lands.25

The Sebettu continue to be found throughout the inscriptions of the remaining Neo-Assyrian kings. Many of their references highlight what is, at this point, the key qualities of the figures: martial strength and far-ranging, often western-focused, movement. Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BCE), for example, refers to them as the “mighty lords, who lead my troops, who strike down [my enemies]” in one inscription,26 reinforcing their position of vanguard. Such language repeats under the inscriptions of Sargon II (721–705 BCE), who describes the Sebettu as the “ones who go before the gods” and help the king achieve victory in battle. The ruler utilizes a nearly identical composition several times, on stela found at the sites of Tell Tayinat, Kition, and Tang-i Var.27 The Seven appear at the end of the lists of deities in the royal inscriptions of Sennacherib (704–681 BCE),28 and Esarhaddon (680–669 BCE),29 with the Sebettu appearing again as the boundary between Assyrian and foreign gods in the list of divine witnesses presented at the close of his succession treaty.30 Once again, the group operates as the most foreign of the familiar: accepted members of the Assyrian pantheon set against the ranks of foreign deities.

At Home on the Margins

From even this brief overview, it seems clear that the Sebettu were connected with the periphery and the edges, and thus employed as leverage while the king was on campaign. The Seven could be specifically invoked to target the more distant areas under the king’s control, or even locations that may have been beyond his current reach. That such areas were also located predominantly to the west may arise from an intersection of frequency – such areas were home to threats that required the Assyrian ruler’s more frequent military attention, and were thus referenced more often in his inscriptions – and utility.

The second quality is the more intriguing of the two. At this point, the Sebettu’s connection to these distant areas under Assyrian control seems to be a clear pattern of their use. However, the questions under- lying this use break down, in essence, to means and motive – or, rather, how were the Sebettu employed, and why were they so suited to this employment. The “how” may be addressed through a consideration of their imagery and epithets, which depict their martial qualities and present them as far-ranging warriors and chaotic but ultimately useful protectors of the king. The underlying “why” governing their use is more complicated, thanks in part to the complex nature of the Seven themselves.

Though the present study has primarily considered one facet of the Sebettu’s use – namely, their representations in royal inscriptions of the Middle and Neo-Assyrian rulers – the Sebettu existed as a complicated tangle of identities and attestations, all of which contributed to their use. Beyond their underlying and inherent demonic nature, the Sebettu were also represented as the Pleiades star cluster. Many deities had astral representations, and it has been argued that the observable actions of those astral bodies effected the behavior of their corresponding deities in texts.31 The Pleiades were clear and easily identifiable, and, moreover, depending on the time of year, would appear on either western or eastern horizon, naturally positioned at the frontiers.

The true victory of the royal inscriptions is the re-positioning of the Sebettu’s violence that was a hallmark of their demonic nature. While their demonic nature set them on the outskirts, it also positioned them to serve as the farthest ranging of any and all members in the service of the king. Such a position also allowed a certain buffer between the ruler and the Sebettu, as if their underlying chaotic nature predisposed them to a violence that could not be fully controlled, only directed towards hopefully useful objectives. These qualities are all on display in the poem of Erra and Išum, a work with a close relationship to the Neo-Assyrian kings’ use of the Sebettu. In the early passages of the text, the Sebettu, frustrated with Erra’s lack of military action and campaigning, stress that their place is on the field, out in the distant steppe. They make it clear that to stay within the city not only strips both them and Erra of any respect due to them as warriors, but also removes their very identity. To stay in the city is to be elderly, a child, or a woman: in military terms, a non-combatant, and such a role is anathema to them. They complain to Erra that the lack of military action, of battle, has caused them to forget the mountain passes they once knew and to lose the ability to draw back their bow. Their arrows are bent and useless, and blades “corroded for want of a slaughter.”32 Warfare and combat is not just one expression of the Sebettu’s abilities, but a fundamental quality of their character. In this regard, Erra and Išum serves as both a reinforcement of the destructive, demonic nature the Sebettu possess even as deities, and a cautionary tale that, as in the text, that nature, particularly if left idle for too long, could easily turn into a calamitous storm that would decimate the inhabited cities of Mesopotamia, rather than their enemies.

Such qualities made the group a readily available and attractive aid to the Middle and Neo-Assyrian kings, but one that required care and delicacy in their implementation. In their inscriptions, these rulers could utilize the divine sanction inherent in their own rule to harness the Sebettu, even if only nominally, to their own will and the service of the state. Moreover, the Seven were inherently most useful when positioned at the naturally liminal frontier, where all of their qualities combined to fully support their role in Assyrian royal inscriptions.

When we compare the manner in which the Sebettu appear and are utilized in texts to the wandering monsters discussed earlier, the two differ in mobility and the intent behind that movement. The monsters, aligned with the cultural principles discussed by Cohen in his “monster theses,” move slowly but organically, assimilating to their new environment and cultural context. In doing so, they themselves also shift: their core traits remain present but are altered or embellished to suit the situation wherein they are now found. The Sebettu, on the other hand, are more fixed in their imagery. In general, demons may move about more freely when compared to monsters, which are often rooted to their geographic contexts. By this logic, the Sebettu would less often need to shift to match their surroundings, able to enter a new context without the slower drift seen when monsters move. The Seven are also deliberately employed in their references, invoked for a specific purpose which governs how they are depicted in texts.

(See endnotes and bibliography at source).

Originally published by Advances in Ancient Biblical and Near Eastern Research (AABNER) 1:1 (Spring 2021, 129-148), DOI:10.35068/aabner.v1i1.788, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.