Examining the actions of Napoleon and his army and how that influenced the Egyptians’ perception of Westerners.

By Alexandra Bell

Western Oregon University

Introduction

In 1789 the French Directory authorized Napoleon Bonaparte to invade Egypt, thus introducing Egypt to modern French civilization. At this time Egypt was still ruled by the Mamluks who served under the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire with little to no interference from the far away Porte. As explained by Jeremy Black, neither the Directory nor Napoleon were overly concerned with making enemies of the dying Ottoman Empire:

“Napoleon assumed that the Turks could be intimidated or bribed into accepting the French invasion…”.1

This adverse view of the Porte demonstrates the typical Western behavior and stereotypes towards Muslims and Middle Easterners as weaker than or less than European powers. The French invasion of Egypt cemented already prevalent stereotypes in both the Middle East and the West into the modern era. These stereotypes alongside the Porte’s inability to protect Egypt from invasion “proved” to the West that they were easily able to take territory from the Ottoman Empire and framed this imperialism as re-building civilization that lapsed under Ottoman rule. France’s attempt to colonize Egypt would ultimately fail due to Napoleon’s deplorable actions in Egypt and his false claim to authority despite no military support coming from the Directory (as a result of the blockade set into place by the British and Porte alliance).

In order to discern how the stereotypes of Muslims and Christians were affected during the invasion, this essay will follow the actions of Napoleon and his army and how that influenced the Egyptians’ perception of Westerners. For many historians, Napoleon’s invasion in Egypt marks the French introduction of “modernity” into the Middle East, as historian Ian Coller explains:

The year 1798 has been identified by historians as an event of peculiar significance in the Middle East and the wider Muslim world, even to the point of marking for some the ‘watershed’ of modernity in the region. The presumption of this view is twofold: first, that the society that the French under Napoleon Bonaparte encountered in Egypt was stagnant, characterized by intellectual immobility, social rigidity, and economic paralysis; and second, that the French brought with them previously unknown ideas and social forms drawn from the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, laying the foundations for the transformations that took place in Egypt under the dynasty of Muhammad ‘Ali in the late 1820s.2

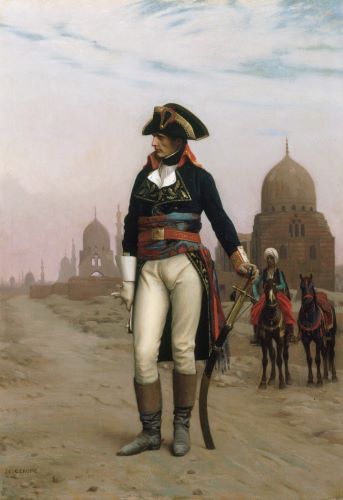

This historical view of the invasion is an example of how the French viewed themselves as superior to the Ottoman Empire before Napoleon conquered Egypt. Historical analysis often frames Westerners as bringers of innovation and modernity because of the white-superiority complex that is prevalent in much of academia as a result of prejudice. Napoleon entered Egypt with lofty aspirations of conquest and a desire to mirror the accomplishments of Alexander the Great and Caesar with France, thus becoming the heir to the Greco-Roman Empire.3 As stated by Shafik Ghorbal, “Bonaparte contemplated nothing less than bringing back to light of day a civilization long buried under the sands of the desert, and ending the long Egyptian night.”4 Napoleon’s goals emphasized the French—as well as the wider European view—that “…Egypt had become the picture of ignorance, poverty, superstition, disease, and contempt for human dignity” under Muslim rule.5 In 1798, Napoleon’s Institut d’Égypte was established specifically to study Egypt with an emphasis on ancient Egypt rather than better a understanding of the modern culture of the Muslim majority. The work created by the Institut d’Égypte, though focusing on ancient artifacts, depicted the Muslims from the point of view of the French. Napoleon’s insistence upon his victories in the Middle East and the propaganda that the artistic works of the Institut d’Egypte spread in France was well received by the public. However, the contemporary Muslim perspective of the French and their actions were preserved in the records of the famous Egyptian historian Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti in his chronicle of the French invasion of 1798.6 The disrespectful approach taken by Napoleon and his army was not lost on al-Jabarti or his fellow Egyptians. Therefore, France was unable to properly assert its control over Egypt and create a prosperous French settlement.

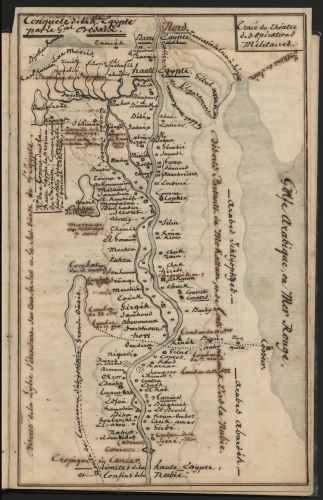

The Invasion of Egypt

Napoleon’s first mistake, which ultimately hindered the creation of a viable colonial settlement in Egypt, was his shortage of Oriental scholars accompanying him on his expedition. As reported by colonial historian David Prochaska, the French had been studying the Orient for over a century, but Napoleon did not bring Orientalists on his expedition. Instead he brought with him young engineers to build roads and canals for French expansion as well as artists to serve for the Institut d’Égypte.7 Thus, there were no qualified specialists to broach the cultural differences between the Muslim majority of Egypt and the French soldiers. Napoleon did take a copy of Voyage en Egypte et en Syrie that detailed how to colonize the region by the French Orientalist Constantin-Francois de Volney.8 But he had no Orientalist academics to advise him on the changing situation in Egypt. Instead of bringing Orientalists as interpreters and translators, Napoleon stopped to conquer Malta for two days in June 1798 and took Arabic speaking Maltese Christians with him to Egypt. Napoleon’s dependence upon these Maltese Christians as translators resulted in a cultural and language barrier between the French meaning and the Arabic understanding because of colloquial differences. For instance, al-Jabarti expressed his disregard for Napoleon and these Christians because of their incorrect grammar.: “…the incoherent words and vulgar constructions which he put into this miserable letter.”9 After conquering Alexandria, Napoleon distributed a proclamation in Arabic to the people of Egypt that was translated from French to Arabic by the Maltese Christians. The proclamation was meant to assure the people of Egypt that Napoleon was a fellow Muslim and that the French had arrived under the Porte’s authority to remove the Mamluks from power—thus, liberating the Egyptian people from Mamluk rule.10 One of Egypt’s leading historians, Shafik Ghorbal, explains that the proclamation did follower closer to Quranic language before being translated into Arabic. Ghorbal goes on to say that the proclamation’s claims were immediately recognized as false by the Egyptian people, but the religious leaders of the Ulema11 urged the people for peace.12 This proclamation of Napoleon’s was his first interaction with the Egyptian people and not only did he lie about having the Porte’s authority and being Muslim, but the Egyptians knew that he was lying. With the foundation of Egyptian’s relationship with Napoleon and the French being based upon a lie, the Egyptians only had mistrust and suspicion for the French.

As a result of Egyptian dissent, the French were not able to gain control over the majority of Egypt during their occupation. Alexandria, Cairo, and Rosetta were the only cities the French had a true grip on in the country.13 Both the Beys14 and the Bedouins continued to resist French rule, especially in the countryside where they were troublesome to French troops. However, Cairo became relatively stable after the French occupied the city in July of 1798. Napoleon created a council of locals to help legitimize his rule, but the council had to follow certain French customs, including wearing a brocade with the French colors upon it. As a symbol of French rule, the brocade embarrassed the members of the High Council who were forced to wear it and caused resentment to rise from the Egyptian leaders of Cairo.15 It was not until October of 1798 that cultural tensions resulted in a violent revolt by the citizens of Cairo against the French soldiers. The Egyptian people had found out that the Porte had declared war on France. Napoleon’s lie about being allied with the leader of the Islamic world was enough to spark a riot against the French invaders. As a result of the riot, 200-300 Frenchmen were killed and ten times as many Egyptians.16 Napoleon treated the offenders harshly and the French army started defiling mosques and holy places and treating the citizens with disrespect.17 Between mutual bad blood between the Muslims and the French, resistance from the Beys previously in charge of Cairo,18 and religious dissent created by French culture in Cairo, it was impossible for the French to hold Egypt as a colony. The French army’s harsh reaction to the revolt in Cairo soured any possibility for cooperation between the French and Muslims in Cairo.

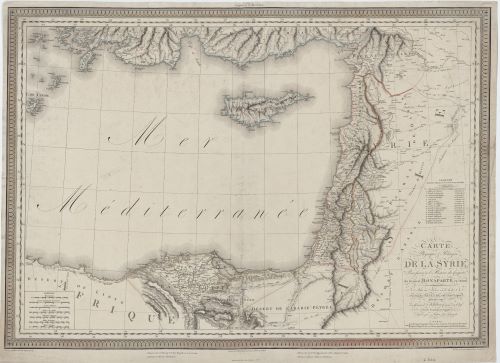

The Syrian Invasion

Napoleon’s short invasion of Syria, while ultimately a failure, urged Austria, Britain, Russia, and the Porte to work together to halt Napoleon’s encroachment upon the Middle East.

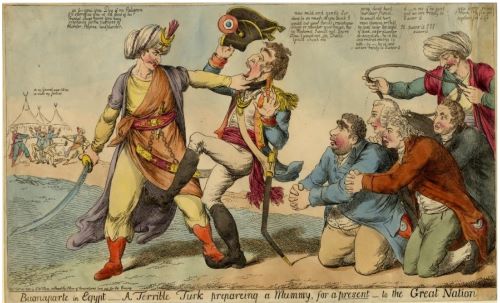

European alliances with the Porte were not a new occurrence, but the significance of this alliance in 1798 was in the Ottoman’s inability to deal with the French without the help of Western powers. The British Navy aided the Porte’s blockade of Egypt. The British were heavily involved with the Porte because they wanted to stop the spread of French influence over trade in the Mediterranean. The English political cartoon pictured above shows a stereotypical Turk threatening a meek Bonaparte.19 Besides this cartoon confusing different cultural practices of the Middle East—and thus creating an inaccurate Muslim caricature—this cartoon shows how prevalent Middle Eastern stereotypes already were in Western Europe during the time of Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt and Syria. Despite Britain’s alliance with the Ottoman Empire, the same negative Muslim stereotypes appeared in British propaganda against the French. However, Britain’s desire to defeat the French and ensure trade access through the Mediterranean was greater than their prejudice of the Islamic world.

Napoleon’s unsuccessful and bloody invasion of Syria cemented his reputation as an immoral and terrible nonbeliever to Muslims and lost him valuable French troops and morale he needed in Egypt. Napoleon did not have the troops nor the arms to successfully take Syria, and as a result, he massacred prisoners of war when he took Jaffa in March of 1799. His ruthlessness in Jaffa did not stop there, as he left members of the French army too sick or injured to travel to die.20 Napoleon’s impatience and unpreparedness ultimately caused him to lose against the Pasha of Acre—known as Djezzar the Butcher—in May of 1799. In spite of the alliance between the Porte and Britain, the Pasha killed all Christians in Acre during the “siege,” despite receiving significant help from Britain.21 This immediate distrust for Christians was a direct result of Napoleon’s propaganda and upheaval of the social order in Egypt. The tensions between Christians and Muslims in the Middle East continued well into the nineteenth century and affected future relations between the two cultures within the Ottoman Empire.

The Legacy of Napoleon

When Napoleon left Egypt for France, the religious peace that had existed in the Ottoman Empire before the invasion of Egypt had been disrupted because of the French. Various groups of Middle Eastern Christians had worked together with the French during the occupation in order to gain greater social mobility. But after command fell to General Menou, the French were quick to distance themselves from these Christians.22 Unlike Napoleon, Menou—a convert to Islam—understood that the French needed to attach themselves to the majority Muslim population rather than create suspicion by favoring the Christians. The change in leadership was not enough to undo the damage done to French reputation, or the scorn for Christians. In 1800 these tensions rose until another riot broke out in Cairo, and the Coptic Christian quarter was attacked. When Napoleon’s troops finally pulled out of Egypt in 1801, the protection they offered the Christians in the area ended. The invasion increased religious tensions between Muslims and Christians—particularly in Egypt—without offering protection to the Christians that helped the French and profited off the invasion.

Although the French invasion had failed, it signaled to Europe and the Ottomans that the Empire was in decline and vulnerable to colonization by Western powers. The Porte used this Western intervention as a chance to learn about their society, culture, and government in the mid-nineteenth century. These implementations can be seen in the Ottomans’ nineteenth-century reforms which attempted to better centralize the government and to preserve the authority of the Porte over the Middle Eastern world. Comparable to the French’s attempt to equalize Egyptian society based on the Revolutionary ideal of equality of the people, the Ottoman Empire began removing the special privileges allotted to its Muslim citizenry (as well as the change to individual tax instead of the traditional communal taxes). This further incensed religious tensions between the Muslim majority and the Christian and Jewish minorities and would further the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Opinion about Westerners and Christians of any kind were at an all-time low after the French invasion ended in 1801. At first Napoleon tried to win the alliance of the Muslim population in Egypt when he arrived and proclaimed himself a fellow Muslim working with the Porte to end Mamluk rule, but that stopped after the first riots in Cairo. During the first riot in Cairo in October 1798, it became clear that Muslims were loyal to the Porte and would not heed French rule without significant struggle. This caused the French to retaliate against the citizens of Cairo with violence and complete disrespect for the local Mosques. Al-Jabarti’s account of the events in Egypt showed the French as dirty, immodest, and irreligious. French soldiers trampled through mosques in their shoes, didn’t understand Arab culture, and favored Christians in the area over the majority Muslim population.23 His account demonstrates how the French were viewed by the Muslims of Cairo at the time. The attitude towards the French and their Christian allies in Egypt inhibited the work of those attempting cross-cultural relations well into the modern era.

Conclusion

Napoleon’s upheaval of the Ottoman Empire’s loose government structure and religious tolerance left Egypt in a power vacuum once the French were finally pushed out of Egypt in 1801. The failure of the French to occupy Egypt destabilized the region’s diverse religious community, but also signaled to the West that the fringes of the Ottoman Empire was weak to Western influence. Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt created a lasting—but not a positive—impact upon the Middle Eastern perspective of Westerners while opening the region up to European powers. Before 1798, the West had not been able to gain significant victories against the strength of the Ottoman Empire. This changed as Napoleon displayed the weakness in the Ottomans’ decentralized power structure. Egypt’s prime location in the Mediterranean and the Ottomans’ weakened Empire gave France the opportunity to take Egypt and thereby gain much needed economic revenue while gaining an advantage over British trade in the region. Napoleon’s show of military force and temporary occupation and brutality in Egypt and Syria were regarded with alarm by the Ottomans: How could French infidels defeat Muslims? This Western invasion compelled the Porte to reassess the structure of the Ottoman Empire and would lead to investigation of Western society and beliefs. Napoleon’s invasion also resulted in the introduction and escalation of negative attitudes about Muslims and Middle Easterners in Western Europe.

Stereotypes perpetuated about Christians and Muslims would continue to be associated with Westerners and Middle Easterners into the modern era as a result of Napoleon’s failed invasion of Egypt. The Muslims in Egypt held loyalty for the Ottoman Empire because of the belief in the greater Muslim community. Napoleon was obviously not Muslim—despite his claims to the contrary—and the actions of him and his army in Egypt tainted public opinion against the Europeans. Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt divided the culturally and religiously diverse region; as a result, Westerners were looked at with resentment and disgust by the Egyptians. The relationship between the French and the Middle Eastern Christians sowed discord amongst the Muslim majority and the Christians that had not been there before—as shown by the second riot in Cairo that resulted in attacks on the Coptic Christian quarter. The Napoleonic invasion of Egypt allowed for ancient stereotypes to persist into the modern era—thus continuing to bring discord between West Europe and the Middle East.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Jeremy Black, “Napoleon’s Impact on International Relations,” History Today, 48 (2) (1998), 46.

- Ian Coller, “A Rough Crossing” in Arab France Islam and the Making of Modern Europe, 1798-1831 (Berkeley Calif.: University of California press, 2011), 31.

- Coller, “A Rough Crossing,” 33.

- Shafik Ghorbal, The beginnings of the Egyptian question and the rise of Mehemet Ali: A study in the diplomacy of the Napoleonic era based on researches in the British and French archives (New York: AMS Press, 1977), 33.

- J. Christopher Herold, Bonaparte in Egypt (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1963), 138.

- Abd Al-Rahman Al-Jabarti, Napoleon in Egypt: Al-Jabartis Chronicle of the First Seven Months of the French Occupation, 1798, trans. Shmuel Moreh (Princeton: Markus Winner Publishing, 2003).

- David Prochaska, “Art of Colonialism, Colonialism of Art: The Description de l’Egypte,” LEsprit Créateur 34, no. 2 (1809-1828), 74-90.

- Prochaska “Art of Colonialism, 74.

- Al-Jabarti, Napoleon in Egypt, 24-33.

- Ghorbal, The beginnings of the Egyptian question, 47.

- The Ulema are Muslim scholars that specialize in Islamic law and theology.

- Ghorbal, The beginnings of the Egyptian question, 48.

- J. Christopher Herold Bonaparte in Egypt (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1963), 138.

- Bey is the Turkish title for chieftan given to leaders of differently sized regions throughout the Ottoman Empire.

- Coller, “A Rough Crossing,” 36-37.

- Prochaska, “Art of Colonialism,” 74.

- Prochaska, “Art of Colonialism,” 74.

- Ibrahim Bey and Murad Bey were the joint rulers of Egypt before Napoleon’s invasion.

- Charles William and S.W. Fores, “Buonaparte in Egypt–a terrible Turk prepareing a mummy for a present–to the Great Nation (1798),” Napoleonic Satires (Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library). https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:232200/.

- Herold, Bonaparte in Egypt, 273-275.

- Herold, Bonaparte in Egypt, 141-275.

- Coller, “A Rough Crossing,” 37-39.

- Al-Jabarti, Napoleon in Egypt, 19-117.

Bibliography

Al-Jabarti, Abd Al-Rahman. Napoleon in Egypt: Al-Jabartis Chronicle of the First Seven Months of the French Occupation, 1798. Translated by Shmuel Moreh. Princeton: Markus Winner Publishing, 2003.

Al-Jabartī, Abd Al-Rahman. Abd Al-Raḥmān Al-Jabartīs History of Egypt. Ed., Moshe Perlmann, Thomas Philipp, and Guido Schwald. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag Stuttgart, 1994.

Black, Jeremy. Napoleon’s impact on international relations. History Today, 48 (2), 1998, 45-51.

Bonaparte, Napoleon I. Military journal of General Buonaparte : Being a concise narrative of his expedition from Egypt into Syria, in Asia Minor: Giving a succinct account of the various marches, battles, skirmishes, and sieges, including that of St. John D’Acre, from the time he left Cairo, until his return there. : Together with an account of the memorable battle of Aboukir, and recapture of the fortress. (Early American imprints. First series ; no. 38024). Baltimore: Warner & Hanna, 1800.

Bonaparte, Napoleon. “Napoleon’s Addresses: The Egyptian Campaign.” Research Subjects: Napoleon Himself. January 2003. Accessed November 25, 2018. https://www.napoleon-series.org/research/napoleon/speeches/c_speeches2.html.

Cole, J. Napoleon’s Egypt : Invading the Middle East (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Coller, Ian. “A Rough Crossing.” In Arab France Islam and the Making of Modern Europe, 1798-1831. Berkeley Calif.: University of California Press, 2011.

Dennis, Alfred. Eastern problems at the close of the eighteenth century. Cambridge, Mass.: Columbia University, 1901.

Denon, V. Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt. (Middle East collection). New York: Arno Press, 1973.

Ghurbāl, M. The beginnings of the Egyptian question and the rise of Mehemet Ali : A study in the diplomacy of the Napoleonic era based on researches in the British and French archives. New York: AMS Press, 1977.

Herold, J. Bonaparte in Egypt. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1963.

Miller, Susan Gilson. Disorienting Encounters: Travels of a Moroccan Scholar in France in 1845-1846: The Voyage of Muhammad Aş-Saffār. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Prochaska, David. “Art of Colonialism, Colonialism of Art: The Description De L’Égypte (1809–1828).” LEsprit Créateur 34, no. 2 (1994): 69-91. doi:10.1353/esp.1994.0057.

Shaw, S. Ottoman Egypt in the age of the French Revolution. Harvard Middle Eastern monographs 11. Cambridge: Center for Middle Eastern Studies of Harvard University by Harvard University Press, 1966.

William Charles and Fores S.W. Buonaparte in Egypt–a terrible Turk prepareing a mummy for a present–to the Great Nation (1798). Prints, Drawings and Watercolors from the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Napoleonic Satires. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library. https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:232200/

Originally published by Digital Commons@WOU (Western Oregon University), Phi Alpha Theta 9, 07.22.2021, under the terms of an Open Access license.