By 1675 the English Atlantic political economy was well beyond the pioneer dispersal stage.

By I.K. Steele

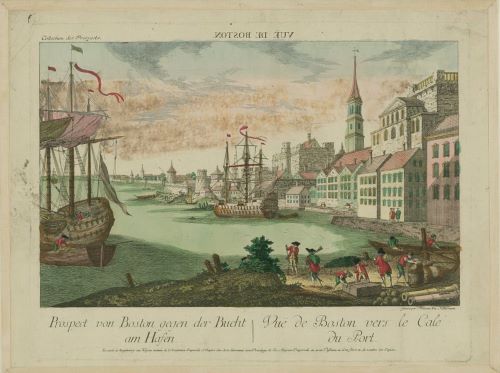

Amid a fiery blaze, visible sixty miles at sea, ‘Some gentlemen took care to preserve Her Majesties Picture that was in the Town-House’.1 It was a small gallantry, to be expected of men of their rank in the Queen’s dominions, but not quite what we have come to expect in Boston, Massachusetts in 1711. These gentlemen, like those who passed a New Hampshire law requiring all members of their House of Assembly to wear swords,2 were among those who were turning colonies into English Atlantic provinces. Yet their story belongs too easily and too exclusively to American colonial rather than British imperial history.

A whole certainly can be much less than its parts if the whole is the written history of the first British empire. Fifty years ago The Cambridge History of the British Empire was launched with a spacious and well-manned volume entitled The Old Empire from the Beginnings to 1783,3 and the ‘imperial school’ of American colonial history was flourishing. Although two generations of scholars have revolutionised every aspect of this subject-including its boundaries-this has been accomplished with little deliberate interest in the history of the first British empire as a whole.4 The habit of drawing Clio in national costume seems as ubiquitous as ever, and the empire is easily seen as an unusable past or a mild embarrassment to its successor states. The neglect of this subject owes even more to the fact that the new ways in history are specialised and comparative. Scholarly attention has been shifting from structures to functional units, from theory to practice, and from the general to the particular. These trends have meant that the first British empire has continued to attract less scholarly interest than have its successor states.

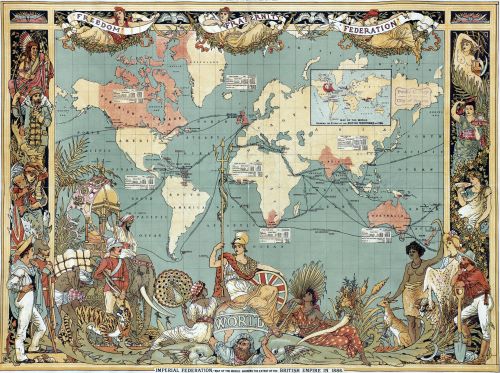

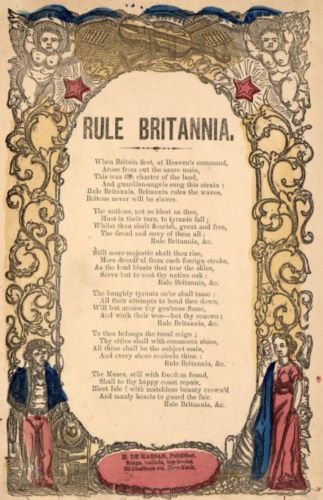

A review of some recent literature from the perspective of the English Atlantic empire draws attention to several themes, and concentration upon the lifetime 1675 to 1740 brings ‘provincial’ themes into sharpest focus. By 1675 the English Atlantic political economy was well beyond the pioneer dispersal stage, and patterns of much subsequent development were already present. This was the lifetime between the founding of the Lords of Trade and the Cartagena expedition. It was the long lifetime between the founding of the Royal African Company and the Stono rebellion, or between the founding of the Royal Observatory and Harrison’s solution to the problem of longitude. This was also the span between Wycherly’s The Country Wife and Thomson’s Rule Britannia, and between the Atlantic mission of George Fox and that of George Whitefield. Despite the well-known centrifugal tendencies that operated in this period, colonial fathers could die in 1740 without hearing a whisper of the coming of the American Revolution. In this provincial lifetime the integration, specialisation, and interdependence that grew in London’s more immediate economic, social and political hinterlands5 was carried to the Atlantic colonies with notable success.

Most Englishmen lived in London’s provinces, whether in rural England, provincial towns, or transatlantic colonies. The county, town, or colony was the context within which most of life was lived;6 with the ‘English nation’ as a general boundary between friends and enemies and a metaphor for the public good. Compared to the lifetime before 1675, migration within England, between England and the colonies, or even between colonies, was less endemic7-with the notable exceptions of the city of London, the colony of Pennsylvania, and the forced migration of Africans to the New World colonies. English population grew very little, grain prices were modest and quite stable, and no crises of subsistence occurred there or in the colonies.8 In these respects, too, the comparisons with the previous lifetime are striking. The mortality crisis of the 1640s, the economic and political problems of the 1620s and 1640s, and what historians have called The Crisis of the Aristocracy, ‘the storm over the gentry’, or ‘the general crisis of the seven-teenth century’,9 all point to the tensions and disruptions that prompted internal migration, migration to continental Europe, and a major early Stuart migration to the new world. Studies of county life in this earlier lifetime have confirmed the general picture, but have also documented the strength of provincial life, and its power to resist centralisation by early Stuart or Cromwellian government.10 Social history, especially local studies of villages, cities, and counties, have challenged the historical assumptions of a unified England with outlying colonies. London’s provinces existed in some variety on both sides of the Atlantic, and the new world provinces were not automatically different for being united to the metropolis by water rather than by land.

Appreciation of the links between various aspects of life is one of the special challenges of historical study, and a tendency towards ‘total history’ has long been part of British imperial history.11 Yet a scholar’s assumptions, research subjects, methods, and preoccupations all tend to emphasise one aspect, be it economic, or social, or political, and to regard the other two as subsidiary subjects if not dependent variables. This exploration of the provincial life of the English Atlantic is organised to focus, in turn, upon each of these aspects.

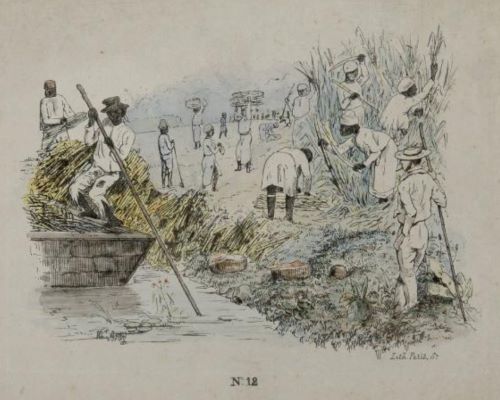

The century after the restoration of Charles II has special attraction for economic historians concerned with the origins of industrial development and ‘modernisation’. E. A. Wrigley’s suggestive model, outlining the import-ance of London’s growth in England’s economic unification,12 can usefully be extended to include the English Atlantic. If the agriculture, industry, and crafts of England were being transformed to respond to the phenomenal growth of the London market, the economic survival of the transatlantic provinces depended upon the development of marketable staples or related activities. London was the major source of credit, the major market, the logical entrep6t, though this natural preference had to be reinforced by war, by trade legislation, and by colonial administration. Economic specialisation in the colonies presumed maritime access to markets, and also presumed sea-borne sources of most needed goods. Thus interdependence grew with specialisation and economies of scale: plantations were among the prototypes of industrial production, profitable but vulnerable elements in the emerging English Atlantic economy.

Although the economic history of the English Atlantic has not been subjected to recent synthesis,13 the field has been ably surveyed in the broader comparative studies by Ralph Davis and K. G. Davies.14 The best short economic histories of pre-industrial England. including those by C. Wilson, L. A. Clarkson and D. C. Coleman,15 are forced, by the recent riches of their field, to adopt a customs officer’s perspective on the ‘foreign plantations’. Studies of overseas trade and the shipping industry all assert the importance of the staple trades in the English re-export trade and in ship utilisation.16 Yet the colonial staple trades are now likely to be seen primarily as sources of profit for London merchants and the English government, and are seldom credited with transforming England to anything like the degree claimed by some pamphleteers at the time and some historians since.17

By 1675 those who had migrated to escape the Old World were succeeded or outnumbered by those who intended to reap the harvest of the New World. Effort to improve upon a rude sufficiency drew colonists into the English Atlantic market economy.18 The wilderness may well have been a subsequent source of colonial uniqueness, but it was at the edge of the real development of these provinces. Access to sea-borne commerce was more advantageous to colonists than to most other Englishmen.

Discovery and development of a marketable staple product was crucial to the shape of colonial societies, as H. A. Innis, M. H. Watkins, R. F. Neill, R. E. Baldwin, and D. C. North have emphasised.19 Ironically, the first of the staples Innis studied, The Cod Fisheries,20 could support contrasting economic and social structures in Newfoundland and New England. The English Newfoundland fishery remained West Country based into the eighteenth century, with international rivalry and fishing interests both helping to retard settlement on the island itself. C. Grant Head has emphasised the increased role of the ‘wintering people’ in the onshore fishery after the 1730s, and the shift of West Country fishermen from the onshore fishery to the formerly French-dominated Banks fishery proper.21 In contrast, New England fisheries supported local village life from the beginning, but could reach out to Canso or Newfoundland with minimal local commitments. As the most perishable and difficult staple to regulate, fish was not susceptible to the entrep6t market structure of other colonial staples. However much it might be prized as a nursery of seamen and a source of foreign earnings, the fishery remained a staple of limited fiscal potential and administrative interest.22

Like the Newfoundland fishery, the English fur trade could operate as an English-based extraction trade or as a colonial traffic supporting a major colonial town like Albany. E. E. Rich’s institutional study is the basis for the more recent work on the Hudson’s Bay trade.23 A. J. Ray and A. Rotstein have explored the price mechanisms and Indian perceptions of the trade,24 and G. Williams has documented the continuing lure of the North-West Passage through the eighteenth century.25 Although the northern English approach to the fur trade generated little local development beyond the Bay factories, the New York fur trade was funnelled through the substantial town of Albany in the new world, and was free of monopoly in its English markets even after fur was ‘enumerated’ in 1722. The economics of the Albany fur trade have received attention recently,26 though less than have other features of the life of the Indians who traded at Albany.27 The fur trade and the fish trade have been the basis for a staple theory of economic growth, yet the range of possible economic structures, the limited ancillary trades, and the comparatively small scale of both trades make them poor examples of the English Atlantic staples.

The sugar trade, that prize of English Atlantic commerce, has long been blessed with good economic historians. The foundation works of Richard Pares put him in a category by himself,28 and the comprehensive volumes by Noel Deerr29 have also survived as major reference works, as has Frank Wesley Pitman’s strangely-titled The Development of the British West Indies, 1700-1763.30 R. S. Dunn’s scholarly and well written Sugar and Slaves31 is a comprehensive study that includes a sound synthesis of the economic aspects of the rise of the planters in the later Stuart period. The economics of integration are more extensively traced in R. B. Sheridan’s Sugar and Slavery. Sheridan divides West Indian economic historians into ‘neo-Smithian’ critics of the value of colonies and ‘neo-Burkean’ advocates of the conviction that empire paid.32 However strange it might seem to apply a neo-Burkean !able to a Marxist argument that English industrialisation owed much to the profits of the sugar trade, this debate goes on, with Sheridan as a self-proclaimed ‘neo-Burkean’.33 But whatever the contentions on that issue, all are agreed that the sugar trade was the exemplar of imperial economic integration accomplished in the lifetime after the construction of the Navigation Acts and the agencies for their enforcement. The loss of the European re-export trade in sugar was a significant blow early in the eighteenth century, but the trade to England itself grew favourably. The sugar trade rested firmly on credit from the Royal African Company, London merchants, and affluent relatives.34 Those colonists who could command the most metropolitan credit on the best terms (for land, slaves, and sugar equipment) won against their less cosmopolitan neighbours.35 This capital and labour intensive trade was firmly bound to the metropolis.

The shuttle of the English sugar fleets to and from the English islands was neither the beginning nor the end of the sugar trade. The loggers, fishermen and seamen of New England; the farmers, millers and merchants of New York and Pennsylvania; these were all linked to the trade in much lighter bondage than that of the African slaves. Richard Pares and Byron Fairchild have sketched aspects of the lumber and provisions trade to the English sugar islands.36 The slave trade has had considerable treatment;37 the Irish provision trade to the islands,38 the molasses trade, and the rum trade from the islands have also had their historians.39 Studies of the development of merchant elites in Boston and Philadelphia40 suggest the important place of the West Indies trade in the creation of these dynasties. J. F. Shepherd and G. M. Walton, as well as D. C. North and R. P. Thomas,41 have found that shipping promoted New England capital accumulation, and the Massachusetts shipowners have been studied intensively.42 For North American merchants, the sugar colonies were a major avenue of profit, especially prized for bills of exchange on London: New England trade directly to England was in furs, skins, train oil, masts and naval stores, but these returns did not cover the cost of English and European goods imported from the metropolis.43

Before 1740 the English colonies did not have extensive trade beyond the empire, though there were beginnings that deserve more study than they have received. The trade in fish to Mediterranean Europe was a direct trade that could be profitable but was subject to heavy competition. The trade to the foreign West Indies was more lucrative, especially to the French islands. By the 1730s two new trades from North America to southern Europe were growing in importance. These were the rice trade from South Carolina, which stayed with English carriers by prescription even though the trade was direct,44 and the grain trade,45 which was destined to become a more important source of profits for New York and Philadelphia merchants. Despite these initiatives, which can easily be exaggerated by hindsight, the English empire was, to a noticeable extent, bound together by the needs and opportunities of the sugar trade during the provincial lifetime discussed here.

Tobacco, the other great staple of the English Atlantic, generated less intercolonial trade than did sugar, but was responsible for more international traffic in Europe after re-export from Britain. J. M. Price has unravelled the complexities of the marketing of tobacco, initially in its connection with Russia, but most recently and masterfully in its links to the French tobacco monopoly.46 The market crisis of the 1670s had accelerated the shift to slave labour and larger holdings, which in turn financed the rise of the gentlemen planters. As A. C. Land’s research has suggested, the tobacco economy was financed on networks of local debt, much of it ultimately owed to English creditors.47 By 1740 the shift to Glasgow as the main British entrepot was a signal of changes in colonial tobacco marketing and credit arrangements. While the London-based agency system still prospered, this new element of consequence was changing the nature of the marketing of Chesapeake tobacco.48

The slaves, who grew much of the tobacco -and even more of the sugar and rice -have been the focus for much recent economic history of both slavery and the slave trade.49 Eric Williams’ ranging and provocative Capitalism and Slavery50 is still a legitimate starting point for recent debates on the origins of racist attitudes,51 the rate of return in the slave trade and slavery,52 and the abolition movement.53 The Royal African Company, by K. G. Davies, is a thorough study of the monopoly company that flourished and failed under the last Stuarts. The African involvement in the slave trade was a significant omission in the Williams thesis, and this aspect of the trade has been illuminated by the works of I. A. Akinjogbin, P. D. Curtin, K. Y. Daaku, D. Forde, A. J. H. Latham, R. Law, M. Priestley, W. Rodney, and R. P. Thomas with R. N. Bean.54 The scale of the forced migration of Africans to the new world has been carefully charted by Curtin55 and this black maritime trade has been surveyed by D. P. Mannix, M. Craton, and Bean.56 London’s dominance in the slave trade, as in the tobacco trade, would lessen before the middle of the eighteenth century, but Liverpool and colonial slavers were of little consequence in the lifetime before 1740.57 English dominance in the English Atlantic slave trade served to reinforce the economic powers that integrated the colonial staple trade into a unified and interdependent economic unit.

Whatever the motives of migrants, the initial economic development of colonies involved grafting these areas to existing economies by the production of marketable staples. It was natural that migrants turned to their own metropolis for needed goods and for the credit to acquire land, labour, and equipment to create returns which paid for imports. The trust that was necessary for business was easier to give to those who share the same family, the same religion, the same language and, when all else failed, the same laws.

Yet such natural inclination did not dominate all colonial Englishmen. Dutch initiative in English colonial sugar development was a clear and early indication that Dutch credit, shipping, and processing industries offered English planters better terms than their own country could. In the third quarter of the seventeenth century English governments consistently and decisively used laws, wars, and elaborate enforcement agencies to exclude the Dutch from what were certainly not to be ‘foreign plantations’.

The rather futile debate over the primacy of merchant wealth or state power in the development of these economic policies has calmed.58 C. D. Chandaman’s The English Public Revenues, 1660-168859 documents the fiscal value of the customs revenues on tobacco and sugar, important income for Charles II and especially James II. Their drive for tighter control of the colonies can now be seen as efficient royal estate management. James II was the last king to control the customs revenues collected in England, revenues which financed expansion of his army. Pursuit of permanent colonial revenues was not so decisively checked after 1689, remaining an active political issue into the eighteenth century.

The burdens of the Navigation Acts upon colonial development has been an enduring topic of research. Although bedevilled by the unfathomable dimensions of smuggling and illegal trade,60 the attempt to measure the price of empire goes on. Computer-assisted research has added new dimensions to this subject, yet the new methods have tended to confirm the classic assessments of L. A. Harper and 0. M. Dickerson,61 that the costs of empire for North American white colonists were modest.62

Economics of development is a current concern which has drawn additional attention to the economic history of England and her colonies in the pre-industrial period. Whether approached from the hypotheses of Watkins, W. W. Rostow, J. A. Ernst and M. Egnal, or North and Thomas,63 the economic development of the English Atlantic in the period 1675 to 1740 did not seriously strain existing economic and political structures. The disruptions of war, the fiscal troubles of the 1730s, French colonial competition, and the problems revealed by the Molasses Act were all strains, but not evidence that the structures were themselves economically inadequate.

As relatively new economic ventures, the colonial trades were opportunities for practising new economic ideas. Commercial capitalism was less re-strained by law and custom in these new areas,64 and the social variety of the colonies adds to their interest for scholars studying cultural influences on economic activity. From an earlier academic concern with the connection between Protestantism and capitalism, recent attention has shifted to the secularising of economic virtue or revisions in the perceived relationship between the self and society. The general inquiries of S. Diamond and Richard D. Brown65 pose questions that are receiving intriguing answers in the works of C. B. MacPherson, J. E. Crowley, J. G. A. Pocock, A. 0. Hirschman and J. 0. Appleby.66

Urban studies are one of the new preoccupations of historians that promise insights for the economic history of the English Atlantic. The frontier was an influence favouring colonial uniqueness, but the towns and cities of the English Atlantic shared many problems and perspectives. Carl Bridenbaugh’s Cities in the Wilderness67 was a herald for this new field. Despite the literature of the economic geographers, historians have seldom approached the analytical sophistication of J. M. Price’s ‘Economic Function and the Growth of American Port towns in the eighteenth century’.68 The economic histories of important provincial ports in England set a high standard, illustrated by recent work on Bristol, Liverpool and particularly the studies of Exeter and Hull.69 The leading towns of provincial America have also been studied, though economics is seldom the dominant theme. Studies of the economic development of the American seaboard town during rapid population growth (Philadelphia), slow growth (New York), and stagnation (Boston) would add to our understanding of development,70 especially if English ports in similar circumstances were studied for comparison.

It was ships and shipping that laced together the ports of the English Atlantic. Studies of the shipbuilding and shipping industries have improved our descriptions of the merchant marine,71 but much more can be done with surviving records. Although economic, political and social exchanges depended upon the communication facilities of the various trades, remarkably little has been done on the pace and pattern of the distribution of news in the English Atlantic.72 Although Alan Pred73 has demonstrated the importance of access to market news for the later growth of New York, nothing has been done to establish the routes of market news in the earlier period.

Economic attraction of colonial specialisation and interdependence lured men in England and the colonies to pursue the integration of the English Atlantic in the lifetime after 1675. There were some colonial statutes that gave advantages to their own merchants and shipowners, and there were objections to imperial legislation and its enforcement,74 but the building of the English Atlantic economy was not seriously challenged from within. The empire was the context within which the emerging colonial elites found the resources for their own advancement.

Social history of the English Atlantic during these years has, for a variety of reasons, received comparatively little direct attention.75 When the ‘imperial school’ of American colonial history prospered, social history was not fashionable, and the political economy of the English Atlantic empire easily became the whole of its history.76 But a much more important reason why the empire is seen without social history is that much of the exciting social history of the last fifteen years has drawn attention to small communities. These ‘community studies’, built on parish records, local censuses, court records and town records, have tended to atomise and specify.77 What Namier did for English political history, the new wave of local studies has done for social history. Expansive assertions about life in ‘England’ or ,America’ are retreating before measured studies of regional differences and their transplant and adaptation to the new world,78 and before careful specific comparisons on a world-wide basis.79 In time, new general patterns can be expected to emerge from this detailed work, allowing better social description of larger social groupings.

English population in the century after 1650 has been explored by scholars seeking the relationship between population growth and the onset of industrialisation. The years 1675-1730 are now seen as having very little population growth.80 For the landed and monied elites, this demographic stability brought consolidation of estates, less political competition, a trade in the export of foodstuffs, and comparative social peace. Generally good harvests,81 together with transportation improvements which minimised local shortages in an integrating English economy,82 broke the traditional connection between poor harvests, increased death rates, and the redirection of capital resources into food and food production.83 The onset of more rapid population increase in the 1730s marked the end of this hiatus, and there are some reasons for thinking that the changes in population were fairly independent of economic determinants, though bringing economic consequences.84 Understandably, the period 1675-1730 did not see much English emigration to the colonies.

Colonial population growth patterns in the same period varied widely. In many colonies the recruiting of labour had been the main immediate concern in promoting migration. The result was a predominantly male population assembled in order to extract wealth, not to start a satellite community. The predominance of males among slaves, servants and masters limited the prospects of family formation and inhibited the emergence of genuine provincial, or creole, societies. The early Chesapeake colonies and the English West Indies were affected in this way,85 though less so than were Newfoundland or Hudson Bay. If the sex ratios dictated that births and marriages would be fewer than deaths, the disease environment reinforced that tendency.86 Most of the staple colonies were not demographically self-supporting in the seventeenth century, as the trade in slaves and servants illustrated, and the English Caribbean remained that way in the eighteenth century as well.87

The dramatic population growth rates usually attributed to colonial North America were neither universal nor immediate. Only those new colonies that attracted migrating families,88 like the Puritan and Quaker settlements, would grow quickly from within rather than from immigration.89 Founding families could accumulate and transmit property more effectively than most other frontiersmen, giving heirs additional opportunities. Quite naturally, economic stability and social stratification, or the foreclosing of opportunity, would come first to the demographically mature and economically limited New England colonies. The demography of the colonies varied greatly, particularly in the seventeenth century, and these differences had essential social and economic implications. Although the demography of the colonies differed from that of the communities from which the migrants came, the subsequent trends in colonial development, particularly in English North America, were towards sex ratios, age distributions, and marriage ages that were more like those in England than had been true at the founding of the colonies.90

Social mobility would appear to be one of the clearest contrasts between the older and newer sides of the English Atlantic. Alan Everitt and Lawrence Stone have explored aspects of elite recruitment in early modern England;91 Stone’s work indicates that there were four routes to rapid social advancement: marriage, the law, government office, and the colonies. The first three of these ‘rapid’ routes to the top of hierarchies presupposed the leisure and resources needed to gain considerable education, if only in manners. Were the Dick Whittingtons of I 675 to 1740 using the colonies as their route to social power in England?

Sugar was the only colonial staple that generated profits sweet enough to allow the most successful to flee the unhealthy colonies and relocate in gentlemanly comfort, if not opulence.92 Physical survival in the islands was one prerequisite for success, but since poor whites outnumbered rich ones, survival was not enough. Sugar was expensive to produce: a planter needed capital and credit, both to start and to build a plantation fortune. English sources of credit would favour the well-to-do, or those judged most likely to honour debts, understand business, and answer letters. Sugar made fortunes, but seldom for those who went out as indentured servants. Men who were illiterate were as unlikely to find fortunes in the sugar trade as they were in the law, government office, or the genteel marriage market. It is likely that there was more opportunity for a woman servant to make her fortune in the seventeenth-century colonial marriage mart,93 but this was a chance that became remote in most colonies as demography changed.

Other avenues of rapid social mobility in Restoration England could be pursued in the colonies as well, even if the colonies in themselves were a less than splendid social escalator. With the hard pioneering life over in most of the colonies, the religious leaders were increasingly joined by attorneys and doctors from England and Scotland who saw opportunities in migration.94 Expansion of government offices could, as in Lord Berkeley’s Virginia or Joseph Dudley’s Massachusetts, afford access to land and local power.95 What has been called The Migratory Elite of the second British Empire,96 had its precursors in the first. The migration of merchants into Massachusetts after 1650 represents another aspect of this process.97 New migrants with capital, credit, royal or proprietary favour found opportunities in the colonies. The development of the newer colonies of the Jerseys and Pennsylvania provided a wider spectrum of mobility, though the advantages of the migrant of the ‘middling sort’ were substantial. While political developments in the north gave opportunity to new men in the later Stuart period, social developments in the Chesapeake gradually strengthened the locally-born elite.98 The Carolina frontier offered most of its new white inhabitants a rude sufficiency, with the economic and political prizes going to the experienced and well-to-do West Indian planters.99 It would be surprising if those with the most advantages did not gain most from the development of new areas, new products, and new markets in the ‘provincial lifetime’.

These same developments tended to limit the opportunities for indentured servants, who earlier could have hoped to become landowners and enjoy minor offices. The work of Russell Menard and Lorena Walsh on seventeenth-century Maryland100 needs imitation wherever sources permit, but recent studies present a plausible picture of increasing stratification and lessening social mobility.101 Again, as in other aspects of recent work in the area, colonial Englishmen’s social existence is increasingly being seen as quite like life in the old world in many respects and colonial developments often served to lessen the differences as time went on.

In ways that are associated with the ideas of Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan,102 the English Atlantic was a paper empire. From laws and instructions to governors, sea captains, or agents, from letters and newspapers, or even from mundane bills of lading, it is evident that the English Atlantic was a society that rewarded literacy. This ‘literal’ culture developed patterns of thought, styles of argument, and views of life that were quite different from the oral traditions that had been inherited and which continued to condition the minds of the illiterate members of the same society.103 For some, literacy was a badge of reformed Christian civilisation, but for others, literacy was a prerequisite for participation in the economic, social and political leadership of the English Atlantic. Illiteracy was linked to dependency, whether that of wife and children, or of the oral culture of Indians and African slaves. Anthropologist Robert Redfield has made a telling distinction between the ‘Great Tradition’ and the ‘Little Tradition’ as coexisting and competing perspectives within a society.104 In the English Atlantic the Little Tradition was oral and local; the Great Tradition was literate and cosmopolitan. The successful provincial had some loyalty to each.

Literacy has become of increasing concern to scholars of early modern England and America. Although the sources are less than ideal, the findings tend once again to reduce the presumed contrasts between English and colonial residents. It is difficult to measure literacy from the signing or marking of wills, but such is the nature of the best evidence about colonial literacy. An adult male literacy rate of about 60 per cent, and female literacy at about 35 percent, is indicated for heads of households in colonial North America in 1660. Although this rate would not change much in Virginia in the next century, K. A. Lockridge has found that male literacy in New England rose dramatically to 70 percent by 1710 and to 85 percent by 1760. The implications of this finding need further study, but suggest that the correlation between status and literacy was not maintained amid declining opportunity in eighteenth-century Massachusetts.105 Fragmentary evidence on literacy elsewhere in English America suggests that white literacy rates were comparable to those of England, though slave illiteracy meant that the plantation colonies were notably less literate than England. It seems safe to assume that only a minority of the adults in England or America could read and write well enough to do so regularly. Whenever information was power, the written word was quicker, more accurate, more complete, exclusive, and it also allowed careful re-readings. In religion, in politics, in family life, and in business, the English Atlantic functioned primarily through, and for, the literate.

Education transmits and preserves more than it innovates, and recent work on American provincial education has re-emphasised the continuities between England and America.106 New England’s strenuous efforts to extend literacy and piety now seem less a special reaction to the fears of barbarism among their children in a frontier society107 than a feature of Calvinist confidence in The Book. The public education laws of New England and of Scotland were established by visibly devout legislators, although the fruits of mass male literacy would come in less devout times. Education to preserve the faith, to preserve civility, and to transmit useful skills seems to have concerned colonials in varying degrees, in keeping with various traditions in Britain, but without any special fervour or neglect that was uniquely colonial.

Provincial newspapers first emerged in the 1690s, bringing local inter-pretations of events and cosmopolitan intrusions upon local life.108 The Worcester Postman (1690) and the Stamford Mercury (1695) were the first two English provincial papers, but it is significant that the Edinburgh Gazette (1699) and the Boston News-Letter (1704) were next, preceding a flood of new English provincial papers during the next 15 years. The Boston News-Letter was so thoroughly committed to delivering court and English news that it has been ignored by historians seeking ‘American’ culture.109 Whatever official censorship was applied to this first North American newspaper, its 300 subscribers110 bought their weekly allotment of metropolitan news because they wanted it. Perhaps there was no apology for a newspaper that was overwhelmingly reprinted from English papers because no apology was necessary.111

Books and their ideas are recognised as an English Atlantic trade of consequence, but the general subject has not received nearly the attention recently lavished on the transit of political ideas,112 or upon the colonial production of books.113 Colonial contribution to the Royal Society may have been marked by provincial deference and search for recognition in the metropolis,114 but N. Fiering has demonstrated how colonial men of letters could keep abreast of new ideas from Europe.115 The Charlestown Library Society boasted of cultural provincialism in its simple Latin motto, ‘Et Artes trans mare currunt’.116

Gentlemanly learning was firmly bound to ‘home’, but we cannot presume that the world of piety and practical knowledge was not also an English Atlantic one. Most visibly transatlantic, the Quaker community exchanged regular epistles and frequent visits of ‘ministering Friends’ who travelled to share and strengthen the faith.117 Although New World Puritanism participated in the theological wars of England more fully in the mid-seventeenth century, religious links continued after the Restoration.118 Anglicanism was the English empire’s official faith, and its place in the colonies tended to grow with the age of the settlements, with the conscious sponsorship of the government, and with the efforts of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.119 The surge of revivalism with which this period ended was itself a transatlantic phenomenon, for George Whitefield and John Wesley could speak to both English and colonial religious sensitivities.

London fashions were regarded with necessary ambivalence in all her provinces. Display of current fashions was a sign of London connections, perhaps advertising links with men of moment in the capital. The migrating elites updated colonial manners and fashions. This was not only true of royal or proprietary governors and their entourages: it was also true of what might be called the professions of pretence-the poorly regulated world of physicians, surgeons, advocates and attorneys. Fashion was a badge of gentility and civility that was worn in most inappropriate circumstances.120 Denunciation of such foppery could also be imported in either secular or religious guise, but the provincial ridicule of pretence revealed a defence mechanism of those who felt culturally inferior.121 Such inferiority could naturally lead provincial Englishmen on either side of the Atlantic to denounce London’s sins while imitating them, and to exalt in the clean and wholesome moral climate of their own communities while importing the latest cultural whimsy from London. Nor should it be surprising if the provincial well-to-do did more of the imitating and the rest of colonial society did more of the denouncing.

Much of the recent social history of the period 1675-1740 has tended to qualify or contradict the easy assertions about how different the new world was from the old in fertility of its people, literacy, and even opportunity. This trend not only narrows the differences between colonial provinces and those on the home island, it suggests cultural continuity as a major value held by colonisers and their children. One of the general questions that emerges from such a sketch, and leads to a consideration of political culture, is ‘How did the new elites elicit or impose social order in these relatively new communities?’

Imperial and colonial politics were vehicles for local social control, and ones which served an emerging elite by assisting, confirming and defending their new social position. English Atlantic politics have long fascinated historians, and the effort lavished on this field has been inspected frequently by a generation of reviewers.122 The mesmerising power of the American Revolution, which fractured a polity regardless of whatever else it did or did not do, ensures continuing attention to political subjects. Unfortunately, this concern can also make colonial grandfathers into veterans of their grandsons’ revolution. Provincial ambivalence was as evident in politics as in social life, for politics invited both the integration of the empire and the integration of the colony to resist that metropolitan initiative, The king’s name was more than a distant benediction of would-be local grandees, for he sent demanding messages and messengers as well. In discussing the politics of integration, it is useful to notice some work concerning political institutions and ideas before considering the larger literature on political practice.

The history of English political institutions received much scholarly attention early in this century,123 and recent studies of ‘Anglo-American’ politics have added comparatively little to that inheritance. The shift of attention has been a dramatic one. Institutional history that presumed more continuity than change was once written as a broad structural analysis of subjects such as royal governorships, the customs service, or the Board of Trade.124 Recent studies tend to emphasise short term political changes as they affected institutions, resulting in more immediacy to particular historical situations and in more narrative structuring of monographs.125 ‘Whig history’ has been so effectively ousted that processes like the ‘origins of cabinet government’ or ‘the rise of the colonial assemblies’ can be seen primarily as the accidental institutional consequences of politics.126

Local political institutions affected political integration decisively, and those of provincial England contrasted sharply with those of the colonies. County political life had its managers, its lord-lieutenants, county courts and locally-oriented J.P.s, but efforts to insulate the counties from central control were hampered by political institutions.127 Parliament was the major political vehicle through which to resist royal or executive centralisation: yet Parliament was itself a centralising, homogenising force. Incorporated towns and cities were in a slightly stronger position, with some political institutions and needs that brought them closer to the transatlantic colonies. A chartered town had courts, an elite that was less hereditary than in the county, and might have a significant population of immigrants and limited social deference.

Charter and precedent were both usable in building the political institutions of the colonies into formal, and eventually formidable, protectors of local rights. Charters were not inviolate, but were rightly seen by royal servants as screening chartered and proprietary colonies from some of the centralising efforts of the royal administration.128 Colonial assemblies, born under charter government but existing in all colonies by 1700, gradually became power centres which imitated the English House of Commons in resisting proprietors, governors, and eventually Parliament itself.129 Strengthening of local assemblies was directed against executive power, but this process was also drawing power from the local level to the provincial, and can be seen as part of the consolidation of provincial elites.130

Colonial provinces may have had a usable institution for resisting royal initiative, but they also had a strong centralising office, that of governor. The monarch was not equal in all of his dominions. The colonial governor had a royal veto which lasted beyond 1707, when it was last used in England. The governor had the power to prorogue, recall, and dissolve colonial assemblies, a power which Parliament had weakened by 1690. In addition, the colonial governor had direct control over the judiciary in his colony.131 English political institutions would undergo substantial changes in the lifetime after 1675, but the existence of colonial assemblies ensured that colonial efforts to emulate English Whiggery produced different results.

In theory, as well as practice, the defence of English provincial autonomy depended upon limiting the power of the king and his ministers, even though Lockean formulations of the rights of the subject could serve Whig ministries as well as their opponents in Parliament and in the counties.132 Whig aristocrats and oligarchs believed their battle cries about liberty as they attacked placement, standing armies, and life revenues for the king. In the corridors of Whitehall or Westminister, or in the somewhat different atmosphere of the colonial assemblies, gentlemen, merchants, and slaveholders found Whiggery, including that of the more radical Eighteenth-Century Commonwealthman,133 entirely appropriate in the struggle for power against the king’s representatives. The English Atlantic of the early eighteenth century shared the developing Whig political theory. It became more wide-spread in the colonies less because they were some inherently ‘liberal fragment’134 than because the emerging political community found this approach appealing and useful, particularly as it was shared by the dominant English political figures.

The practice of politics in the English Atlantic has received a great deal more attention in the last twenty years than has the theory. The atomisation of English politics owes much to the work of L. B. Namier, the first major piece of which appeared (like the first of the Cambridge History of the British Empire) fifty years ago.135 Namier’s major impact on scholarship came after the second World War, when his approach influenced scholars in English and then American colonial studies.136 The approach, which perceives politics as the idea-free art of gathering power for patronage, has appealed both to those historians who are suspicious of ideology and to those whose ideas lead them to emphasise the economic interpretation of political behaviour. Namier’s approach was also supportive of the strong biographical tradition in the writing of English political history, and gave added significance to local and county history as well. Namier’s interpretation and method were developed to understand the generation after 1760, and it is the rather zealous application of this approach to Queen Anne’s reign that has been very effectively challenged.137

Imperial politics of the English Atlantic between 1675 and 1740 exhibited phases, yet there were persisting forces of political integration throughout this period. The monarchy was a shared symbol of social and political order, lending its name to laws, charters and court proceedings. This symbolism had its uses in all the king’s provinces, but was of particular concern in areas where social mobility was more common and deference was less so. The gentlemen merchants of incorporated towns like Hull or Leeds, for example, saw the charter and baronetcies as legitimising their social and political leadership in communities that included immigrants who had never touched their forelock to a merchant. The royal garrison at Hull might even supplement the night watch over property.138 Local notables called courts into session in the king’s name, but they rightly suspected the assizes139 as centralising legal power as effectively as did appeals to higher courts and the lawmaking power of Westminster. The crown was a stabilising symbol, but much of politics was aimed at exploiting that symbol while eroding the crown’s real power.

The crown was not only the formal font of order, it was also at least the formal source of the political patronage that supported many English aristocrats, and the pretensions of officeholders on both sides of the Atlantic. Sophisticated political use of the offices in the gift of the crown was justly feared as a power to overcome all legislative resistance.140 Transatlantic provinces were particularly subject to the integrating power of royal patronage. A new royal governor could bring trouble for the calculations and pretensions of the colonial elite. His power over a few appointments was less important than his nominations for council seats, his control of the magistracy, and his influence over land grants. Governorships were brief and the lobbying of colonials and their agents to oust, obtain, or keep governors was itself a system that bound colonial leadership to English politics.141

Whatever the structural bias of imperial political institutions, they operated in the real and unpredictable world of all politics. The active monarchical drive for order and control that marked the period 1675 to 1688 was unique and formative. The crisis of 1688-9 was shared by the whole empire. The generation 1689-1714 saw several sharp shifts in political power. Then came the generation that achieved, and suffered, political stability. These phases are a simple framework within which some of the recent works of political historians can be viewed.

The English crown was an unusually active agent of political integration between 1675 and 1688. From the fiscal, diplomatic and political rubble of the last Dutch war, a sobered Charles II and his more sober and industrious younger brother, James, began rebuilding the monarchy’s position. Opposition to royal resurgence crystallised into Whiggery, developed new weapons in electoral management, but lost the long and bitter fight to exclude James from the succession.142 Customs revenues on imported colonial staples were a significant part of the royal revenues that were independent of Parliament. Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia hurt that revenue, and prompted closer political management of the colonies. From 1675 the new Lords of Trade and Plantatations began an administrative centralisation,143 and launched the careers of William Blathwayt and Edward Randolph, names synomymous with this centralisation for the next generation.144 In 1685 James gained the monarchy and the life revenues which, in the prosperity of his brief years, yielded enough to allow him more freedom from Parliament.145

The Glorious Revolution was an admission of failure: the king’s political opponents had failed to stop him by constitutional means. The result was an acceptance of unconstitutional means, and significant adjustments to protect against recurrence, while insisting upon the preservative nature of the coup.146 The colonial uprisings in the Dominion of New England and in Maryland have usually been seen as based upon local grievances, which seem sufficient causes.147 What can easily be underestimated, as P. S. Haffenden indicates,148 is that the Revolution was welcomed around the English Atlantic with few regrets and few Jacobites, indeed with something approaching unanimity. Apparently it mattered who was king of England: colonial revolutions occurred only where unofficial news of the royal changes arrived long before any official word reached the colonial executive.149 In general, the revolution showed the political unity of the empire much more than it revealed its diversity.

War is an international test of the ability of a government to marshall resources. William brought a war against the powerful centralising French monarchy, and the war effort brought some of that state power which both the revolution and the war ostensibly opposed. Although there were political concessions to ‘country’ interests in the annual Parliaments, they were voting taxes for expanded government. The fiscal drain was from the North and West to the Southeast. from the landed to the manufacturing and service groups in the nation, and from the provinces to the metropolis.150 For the colonies, the war and its successor would bring more military responsibilities than resources for the governors, but would increase the roles of the governor and the commander of the naval station ships. Assemblies bargained for privileges, paper money issues, or other concessions in return for supply, but an echo of the processes at work in England could be heard in the colonies when they were, rather intermittently, roused to war.151 Colonials fought the French and did so as provincial Englishmen. As with the English governments of these war years, governors had varied success in harnessing factions for the war effort.152 The assemblies would emerge stronger, and the governors weaker, as was true in England, but the wars made colonial dependency on metropolitan warmaking and peacemaking painfully obvious.153

Peace brought a respite from the government drive to assemble resources, eased the tax burden, and promised fewer initiatives at the expense of provincial life, or at least meant that local elites could manage these initiatives. The Whig political triumph was reinforced by helping the Tories commit political suicide, and by reducing the size of the electorate and the frequency of elections.154 While radical Whigs pursued the wars of ideas, the managers of the government focused upon patronage as the purpose of power. Frank acceptance of the enjoyment of office brought consequences that are perhaps easiest seen in the well-documented colonial administrations. The quality of Newcastle’s governors was uneven,155 but that is less surprising or uncommon than was the tendency for appointees to avoid initiatives that would be unpopular and to make compromises for personal peace or profit that permanently shrank the power of the governorship. Whatever power was not sacrificed that way was subject to more intense pressure from England. Patrons of the governor offered him candidates for those few offices that were still part of his direct patronage, offices he should have used to buy or keep political supporters from the local elite. The management of colonial politics had always reached to Whitehall: under Walpole and Newcastle the management of the House of Commons extended all the way to Jamaica and Virginia.156

Achieving ‘political stability’ in Walpole’s England included what can still be called ‘salutary neglect’ of the colonies, if not political stability there as well.157 ‘Robinocracy’ was factious Whiggery, tainted Whiggery, but still seen to be Whig by all but a few. Yet no colonial governor could be a Whig in office, though every one of them had to be a Whig to get that office. If the colonial executive threat to the liberties of the local elite had not been real, it would have been a most useful invention. The colonial assemblies were emulating the House of Commons of the recent past in defending ‘country’ values against the ‘court’. This was not the road to independence, this was the political perspective of an emerging provincial elite anxious and able to consolidate their own power within the English Atlantic.158 The triumph of the Whigs had been better institutionalised in the American and West Indian assemblies that it had been in England.

It was no coincidence that the ‘English nation’ mattered most to the people who mattered most. Those with economic, social, and political ties beyond the local level would include the nobility, the gentry, and the prominent merchants who were the leaders of county, town, or colony. These elites had a fascinating ambivalence towards the metropolis. On the one hand, they were the men of substance who could defend their localities from metropolitan interference; on the other hand, they could gain personal advantage in serving the court or the ‘nation’ as agents of centralisation.159 They could resist royal or parliamentary initiatives with Whig thunder against tyranny, while exercising local political and legal power that was legitimised by the king’s name. They could denounce the London stock-jobbers and goldsmiths while living on money borrowed in the metropolis for fashionable living, for land purchases, for industrial estate development, or even for lending to others in their locality. They could proclaim the moral superiority in the wholesome rural life while displaying their civility via the fashions of London. These paradoxical tensions, which were so cleverly exposed in later Stuart plays,160 are enduring aspects of provincial life.

Recent scholarship suggests that when John Oldmixon claimed ‘I have no notion of any more difference between Old-England and New than between Lincolnshire and Somerset’161 he was stretching a truth less than was once thought. The emergence of English provincial history has destroyed the equation of London and England at the same time as American colonial studies have been challenging notions of a unique America, or what David Hall has called ‘American exceptionalism’.162 The links between what was happening in Stuart and Georgian England and the colonies were not a matter of parallels: the same processes of metropolitan integration were pulling at all London’s provinces.

Of the major aspects of life, the economic attractions of specialisation, interdependence and integration recommended themselves to those provincials able to dominate the new staples of the colonies, or the older ones for the new English markets. The sea allowed colonial integration with little investment in roads or canals. At this provincial stage there was very little resistance, and obvious advantage to economic integration.

Although peopled by many from London’s nearer provinces, the colonies began as social gatherings most unlike home. Demographic, economic, and political development all contributed to the emergence of new world provinces that were much more like the old than the founders would have imagined or intended. Gentility and civility served social purposes amongst provincial elites throughout the empire, mattering even more in London’s more immediate hinterland, where political independence had been effectively lost. In colonial society, the elites could profitably accept English gentility as a social insulator which distinguished themselves from other colonists, Indians and slaves.

The fall of the colonial governors was, and was intended to be, a constitutional replay of the fall of the Stuart monarchy. Colonial leaders maintained their local dominance through political institutions that served both to resist imperial initiatives and to integrate power within the colony itself. Success was not assured, and the generation of war after 1739 would upset the Whig empire in all of its parts, but colonial assemblies did represent a major source of power not available in the same way to English county and town elites.

Colonial elites could serve themselves and call it serving the king or call it serving their electors. But they would have trouble claiming, as the slave or indentured servant might have done, (and as undergraduates continue to do), that ‘The colonies exist for the benefit of the mother country’. Provincial elites were beneficiaries of empire. The ambiguity of being the vehicles of cosmopolitan influence and the defence against that influence did not produce great difficulties. The notion of ‘stacking loyalties’ has been used to good effect in other contexts,163 but has been noticeably absent in explanations of provincials in the first empire. Virginians, like men of Devon, could hold their local loyalty firmly and yet fight as Englishmen. When loyalties clashed, the local one might triumph, but local elites drew power from the unity of the English Atlantic.

Endnotes

- The Boston News-Letter, no. 390, 8 Oct. 1711 and The Diary of Samuel Sewall, 3 vols. (Boston, 1878-1882), II, 323-4.

- D. E. van Deventer, The Emergence of Provincial New Hampshire, 1623-1741 (Baltimore, 1976), 218. An advertised horse race, with a 20 shilling entry fee and a £20 plate, hints at similar influences in Cambridge, Mass. by Sept. of 1715.

- The Boston News-Letter, nos. 594-6. (Cambridge, 1929).

- The imperial perspective is maintained by L. H. Gipson in A Bibliographical Guide to the History of the British Empire, 1748-1776, which is volume 14 of his The British Empire before the American Revolution, 15 vols. (Caldwell, Idaho & New York, 1936-70). Also see his ‘The Imperial Approach to Early American History’ in The Reinterpretation of Early American History, ed. R. A. Billington (San Marino, Cal., 1966), 185-99. Useful recent general bibliographies of American colonial history include: F. Freidel and R. K. Showman, The Harvard Guide to American History, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Cambridge, Mass., 1974); A. T. Vaughan, The American Colonies in the Seventeenth Century (New York, 1971); J. P. Greene, The American Colonies in the Eighteenth Century (New York, 1969); Institute of Early American History and Culture, Books about Early America (Williamsburg, 1970) and its sequel Books about Early America 1970-1975 (Williamsburg, 1976).

- E. A. Wrigley, ‘A Simple Model of London’s Importance in Changing English Society and Economy, 1650-1750’, Past & Present, no. 37 (July 1967), 44-70. The Scottish lowlands had an English provincial culture, but one with cultural, legal, political and economic aspects different from the English colonies. See: J. Clive and B. Bailyn, ‘England’s Cultural Provinces: Scotland and America’, The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. (hereafter cited as W&MQ). xi (1954), 200-13; D. Daiches, The Paradox of Scottish Culture: The Eighteenth Century Experience (London, 1964); J. H. Burns, ‘Scotland and England: Culture and Nationality 1500-1800’, in J. S. Bromley and E. H. Kossman (eds.), Britain and the Netherlands IV Metropolis, Dominion and Province (The Hague, 1971), 17-41; and N. T. Phillipson, ‘Culture and Society in the Eighteenth Century Province: The Case of Edinburgh and the Scottish Enlightenment’, in L. Stone (ed.), The University in Society (Princeton, 1974), 407—48. The emergence of Scotland as a new exemplar for some American colonists in the generation after 1750 needs further study. See Andrew Hook, Scotland and America 1750-1835 (Glasgow, 1975), chap. 2.

- P. Laslett, The World We have Lost (London, 1965), chap. 3; W. G. Hoskins, Provincial England (London, 1963); A. M. Everitt, The Community of Kent and the Great Rebellion, 1640-1660 (Leicester, 1966); and I. Roots, ‘The Central Government and the Local Community’, in E. W. Ives (ed.), The English Revolution 1600-1660 (London, 1968), 34—47.

- J. Cornwall, ‘Evidence of Population Mobility in the Seventeenth Century’, Institute of Historical Research Bulletin, xl (1967), 143-52; A. Everitt, ‘Farm Labourers’ in The Agrarian History of England and Wales, IV: 1500-1640, ed. J. Thirsk (Cambridge, 1967), 399—400; P. Clark, ‘The Migrant in Kentish Towns, 1580-1640’, in Crisis and Order in English Towns 1500-1700, eds. P. Clark and P. Slack (London, 1972), 117-163; P. Slack, ‘Vagrants and Vagrancy in England 1598-1664’, Economic History Review, 2nd ser. (hereafter cited as EcHR), xxvii (1974), 360-79.

- E. L. Jones, ‘Agriculture and Economic Growth in England, 1660-1750: Agricultural Change’, Journal of Economic History (hereafter cited as JEcH), xxv (1965), 1-18; A. H. John, ‘Agricultural Productivity and Economic Growth in England, 1700-1760’, ibid., 19-34; J. D. Chambers, Population, Economy, and Society in Pre-Industrial England (London, 1972). For the grain trade into Massachusetts see D. C. Klingaman, ‘The Coastwise Trade of Colonial Massachusetts’, Essex Institute Historical Collections, cviii (1972), 217-34.

- L. Stone, The Crisis of the Aristocracy, 1558-1641 (Oxford, 1965); J. H. Hexter, Reappraisals in History (London, 1961), 117-62; T. Aston, ed., Crisis in Europe 1560-1660 (London, 1965).

- A Everitt, Change in the Provinces: the Seventeenth Century (Leicester, 1969) is a suggestive general essay. Also see: Everitt, Community of Kent; J. S. Morrill, Cheshire 1630-1660: County Government and Society during the English Revolution (London, 1974); A. Fletcher, A County Community in Peace and War: Sussex 1600-1660 (London, 1976); B. G. Blackwood, The Lancashire Gentry and the Great Rebellion, 1640-1660 (Manchester, 1978).

- W. F. Craven, ‘Historical Study of the British Empire’, Journal of Modern History, vi (1934), 40-1. This essay emphasises the first empire, and makes comparisons with later work possible.

- Wrigley, loc. cit. On London investment in the provinces see J. D. Chambers, The Vale of Trent, 1670-1800 (London, 1957) and compare J. R. Ward, The Finance of Canal Building in Eighteenth Century England (London, 1974); A. H. John, ‘Aspects of English Economic Growth in the first half of the Eighteenth Century’, Economica, xxviii (1961), 188. On the slow growth of ‘country banks’ in English provincial cities (cf. Edinburgh) see M. W. Flinn, The Origins of the Industrial Revolution (London, 1966), 52—4; D. C. Coleman, The Economy of England 1450-1750 (Oxford, 1977), 147; and G. Jackson, Hull in the Eighteenth Century: A Study in Economic and Social History (London, 1972), chap. ix.

- Bibliography of British History: Stuart Period, 1603-1714, 2nd ed., edited by G. Davies and M. F. Keeler (Oxford, 1970) remains the standard bibliography for the later Stuarts, and there are useful additions to be found in W. L. Sachse, Restoration England, 1660-1689 (Cambridge, 1971) and in C. Wilson, England’s Apprenticeship, 1603-1763 (London, 1965). American colonial economic history was carefully reviewed by L. A. Harper, ‘Recent Contributions to American Economic History: American History to 1789’, JEcH, xix (1959), 1-24 and updated ten years later by G. R. Taylor’s American Economic History before 1860 (New York, 1969). Also see Freidel and Showman.

- The Rise of the Atlantic Economies (London, 1973) and The North Atlantic World in the Seventeenth Century (London, 1974) respectively. There is also much that is suggestive in The Cambridge Economic History of Europe: vol. IV, The Economy of Expanding Europe in the 16th and 17th Centuries, E. E. Rich and C. Wilson (eds.), (Cambridge, 1967).

- Wilson, England’s Apprenticeship; L. A. Clarkson, The Pre-Industrial Economy, 1500-1750 (London, 1971); and Coleman, Economy of England. Flinn, Origins emphasises the colonial markets in the period 1740-1760, see chap. iv.

- See: E. B. Schumpeter, English Overseas Trade Statistics, 1697-1808 (Oxford, 1960); P. Deane and W. A. Cole, British Economic Growth, 1688-1959, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, 1967) and N. F. R. Craft, ‘English Economic Growth in the Eighteenth Century: A Re-Examination of Deane and Cole’s Estimates’, EcHR, xxix (1976), 226–35; R. Davis, The Rise of the English Shipping Industry (London, 1962) and his English Overseas Trade 1500-1700 (London, 1963); and the studies gathered as The Growth of English Overseas Trade in the 17th and 18th Centuries (London, 1969) edited by W. E. Minchinton.

- See Coleman, Economy of England, 196-201 for a cautious judgement. Davis, Atlantic Economies emphasises new world trade whereas Jones, foe. cit., John, foe. cit., and E. Kerridge, The Agricultural Revolution (London, 1967) present the case for agricultural growth, as does E. L. Jones, Agriculture and the Industrial Revolution (Oxford, 1975).

- K. Lockridge, A New England Town: The First Hundred Years (New York, 1970); J. Demos, A Little Commonwealth: Family Life in Plymouth Colony (New York, 1970); and P. J. Greven Jr., Four Generations: Population, Land, and Family in Colonial Andover, Massachusetts (Ithaca, N.Y., 1970) are all valuable in appreciating the isolated community. J. T. Lemon, The Best Poor Man’s Country; A Geographical Study of Early Southeastern Pennsylvania (Baltimore, 1972); R. L. Bushman, From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765 (Cam-bridge, Mass., 1967) and van Deventer, Provincial New Hampshire study somewhat larger subjects that demonstrate the impact of the market economy.

- R. F. Neill, A New Theory of Value: The Canadian Economics of H. A. Innis (Toronto, 1972); M. H. Watkins, ‘A Staple Theory of Economic Growth’, Canadian Journal of Economic and Political Science, xxix (1963), 141-58; R. E. Baldwin, ‘Patterns of Development in Newly Settled Regions’, Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies, xxiv (1956), 161-79; D. C. North and R. P. Thomas, ‘An Economic Theory of the Growth of the Western World’, EcHR, xxiii (1970), 1-17.

- (New Haven, 1940).

- Eighteenth Century Newfoundland (Toronto, 1976).

- The timber trade was another central feature of New England economics, best seen in the development of New Hampshire. See J. J. Malone, Pine Trees and Politics: The Naval Stores and Forest Policy in Colonial New England 1691-1775 (Seattle, 1964) and van Deventer, Provincial New Hampshire, especially chap. v.

- See his The History of the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1670-1870, 2 vols. (London, 1958-9) and his more general The Fur Trade and the Northwest to 1857 (Toronto, 1967).

- A. J. Ray, Indians in the Fur Trade: their role as trappers, hunters, and middlemen in the lands southwest of Hudson Bay, 1660-1870 (Toronto, 1974) and A. Rotstein, ‘Fur Trade and Empire: An Institutional Analysis’, Ph.D., thesis University of Toronto, 1967.

- G. Williams, The Search for the Northwest Passage in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1962).

- T. E. Norton, The Fur Trade in Colonial New York, 1686-1776 (Madison, Wise., 1974); D. A. Armour, ‘The Merchants of Albany, New York 1686–1760’, Ph.D. thesis, Northwestern University, 1965; S. E. Sale, ‘Colonial Albany: Outpost of Empire’, Ph.D. thesis, University of Southern California, 1973.

- F. P. Prucha, A Bibliographical Guide to the History of Indian-White Relations in the United States (Chicago, 1977) is a full survey of recent work.

- War and Trade in the West Indies, 1739-1763 (Oxford, 1936); A West India Fortune (London, 1950); Yankees and Creoles (London, 1956); Merchants and Planters (New York, 1960).

- N. Deerr, History of Sugar, 2 vols. (London, 1949).

- (New Haven, 1917).

- (Chapel Hill, 1972).

- (Baltimore, 1973), 5-17.

- The dabate can be followed in: R. B. Sheridan, ‘The Wealth of Jamaica in the Eighteenth Century’, EcHR, xviii (1965), 292-311; R. P. Thomas, ‘The Sugar Colonies of the Old Empire: Profit or Loss for Great Britain’, ibid., xxi (1968), 30-45; R. B. Sheridan, ‘The Wealth of Jamaica in the Eighteenth Century: a Rejoinder’, ibid., 46-61; R. K. Aufhauser, ‘Profitability of Slavery in the British Caribbean’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, v (1974), 45-67; J. R. Ward, ‘The Profitability of Sugar Planting in the British West Indies, 1650-1834’, EcHR, xxxi (1978), 197-213.

- See K. G. Davies, The Royal African Company (London, 1957), chaps. iv, vi; Sheridan, Sugar and Slavery, chaps. xii, xiii.

- R. B. Sheridan, ‘The Rise of a Colonial Gentry: A Case Study of Antigua, 1730-1758’, EcHR, xiii (1961), 342-57; Dunn, Sugar and Slaves, especially chaps. ii, iv-vii.

- Pares, Yankees and Fairchild, Messrs. William Pepperre/1, Merchants at Piscataqua (Ithaca, N.Y., 1954).

- See below, notes 51-7.

- F. G. James, ‘Irish Colonial Trade in the Eighteenth Century’, W&MQ, xx (1963), 574-84, and his Ireland in the Empire 1688-1770 (Cambridge, Mass., 1973).

- G. M. Ostrander, ‘The Colonial Molasses Trade’, Agricultural History, xxx (1956), 77-84; W. D. Roulette, ‘Rum Trading in the American Colonies before 1763’, The Journal of American History, xxvii (1934), 129-52.

- B. Bailyn, The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, Mass., 1955) and F. B. Tolles, Meeting House and Counting House (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1948). W. I. Davisson and L. J. Bradley, ‘New York Maritime Trade: Ship Voyage Patterns, 1715-1765’, New York Historical Society Quarterly, Iv (1971), 309-17 suggests the prominence of the island trade there as well.

- Shipping, Maritime Trade, and the Economic Development of Colonial North America (Cambridge, 1972); North and Thomas, foe. cit. and D. C. North, ‘Sources of Productivity Change in Ocean Shipping, 1600-1850’, in R. W. Fogel and S. L. Engerman (eds.), The Reinterpretation of American Economic History (New York, 1971), 163-74.

- B. and L. Bailyn, Massachusetts Shipping, 1697-1714 (Cambridge, Mass., 1959).

- This trade needs further study. Aspects of the naval stores trade are the focus of Malone, Pine Trees, and J. J. McCusker, Money and Exchange in Europe and America, 1600-1775: A Handbook (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1978) will ease the calculations here as elsewhere.

- C. D. Clowse, Economic Beginnings in Colonial South Carolina, 1670-1730 (Columbia, S.C., 1971); P. H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stano Rebellion (New York, 1974), chap. iv.

- J. G. Lydon, ‘Fish and Flour for Gold: Southern Europe and the Colonial American Balance of Payments’, Business History Review, xxxix (1965), 171-83; D. Klingaman, ‘The Significance of Grain in the Development of the Tobacco Colonies’, JEcH, xxix (1969), 268-78; P. G. E. Clemens, ‘From Tobacco to Grain: Economic Development on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, 1660-1750’, Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin, 1974.

- ‘The Tobacco Adventure to Russia, 1676-1722’, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, new series, vol. Ii, pt. 1 (1961), 3-120; France and the Chesapeake, 2 vols. (Ann Arbor, Mich,. 1973).

- ‘Economic Base and Social Structure: The Northern Chesapeake in the Eighteenth Century’, JEcH, xxv (1965), 639-59; and ‘Economic Behavior in a Planting Society: The Eighteenth Century Chesapeake’, Journal of Southern History, xxxiii (1967), 469-85.

- J. M. Price, ‘The Rise of Glasgow in the Chesapeake Tobacco Trade, 1707-1775’, W&MQ, xi (1954), 179-200; T. M. Devine, The Tobacco Lords (Edinburgh, 1974); L. M. Cullen, ‘Merchant Communities, The Navigation Acts and the Insh and Scottish Responses’, and T. M. Devine, ‘Colonial Commerce and the Scottish Economy, c. 1730-1815’, both in Comparative Aspects of Scottish and Irish Economic and Social History 1600-1900 (Edinburgh, 1977).

- Bibliographies include: E. Miller, The Negro in America: A Bibliography (Cambridge, Mass., 1966); W. D. Jordan, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1968), pp. 586-614; J. M. McPherson, Blacks in America: Bibliographical Essays (New York, 1971); P. H. Wood, “I Did the Best I Could for My Day”: The Study of Early Black History during the Second Reconstruction, 1960 to 1976′, W&MQ, xxxv (1978), 185-225.

- (London, 1944).

- Williams’ argument, that slavery led to discrimination, has been favoured by economic and by ‘liberal’ historians. 0. and M. F. Handlin, ‘Origins of the Southern Labour System’, W&MQ, vii (1950), 199-222 and S. Elkins, Slavery (Chicago, 1959) are significant here. The primacy of prejudice as preceding and causing slavery has been argued by C. Degler, ‘Slavery and the Genesis of American Race Prejudice’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, ii (1959-60), 49-66 and by Jordan, White over Black. Jordan’s ‘Modem Tensions and the Origins of American Slavery,’ Journal of Southern History, xxviii (1962), 18-33, exposed the false dichotomy of the debate and offered a sensible middle ground.

- See above, note 33. Another centre of this debate concerns the period after 1760. Highlights include: R. W. Fogel and S. L. Engerman, Time on the Cross, 2 vols. (Boston, 1974); H. G. Guttman, Slavery and the Numbers Game: A Critique of Time on the Cross (Urbana, Ill., 1975). On the related question of the slavers’ profits see R. P. Thomas and R. N. Bean, ‘The Fishers of Men: The Profits of the Slave Trade’, JEcH, xxxiv (1974), 885-914, and the following note.

- R. Anstey, The Atlantic Slave Trade and British Abolition, 1760-1810 (London, 1974); H. Temperley, ‘Capitalism, Slavery and Ideology’, Past and Present, no. 75 (May 1977), 94-118; S. Drescher, Econocide: British Slavery in the Era of Abolition (Pittsburgh, 1977).

- I. A. Akinjogbin, Dahomey and Its Neighbours, 1708-1818 (London, 1967); P. D. Curtin, Economic Change in Precolonial Africa: Senegambia in the Era of the Slave Trade (Madison, Wise., 1975); K. Y. Daaku, Trade and Politics on the Gold Coast 1600-1720 (Oxford, 1970); D. Forde, ed. Efik Traders of Old Calabar (London, 1956); A. J. H. Latham, Old Calabar, 1600-1891 (London, 1973); R. Law, The Oyo Empire c. 1600-c. 1836 (Oxford, 1977); M. Priestley, West African Trade and Coast Society, a family study (London, 1969); W. Rodney, A History of the Upper Guinea Coast, 1545-1800 (Oxford, 1970); Thomas and Bean, ‘Fishers of Men’.

- The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census (Madison, Wise., 1970).

- D. P. Mannix and M. Crowley, Black Cargoes (New York, 1962); M. Craton, Sinews of Empire: A Short History of British Slavery (London, 1974); R. N. Bean, The British Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, 1650-1775 (New York, 1975).

- G. Ostrander, ‘The Making of the Triangular Trade Myth’, W&MQ, xxx (1973), 635-44; H. S. Klein, ‘Slaves and Shipping in Eighteenth-Century Virginia’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, v (1975), 383-412; P. G. E. Clemens, ‘The Rise of Liverpool, 1665-1750’, EcHR, xxix (1976), 211-25.

- See D. C. Coleman, Revisions in Mercantilism (London, 1969).

- (Oxford, 1975). Also see E. A. Reitan, ‘From Revenue to Civil List 1689-1702’, Historical Journal, xiii (1970), 571-88 and C. Roberts, ‘The Constitutional Significance of the Financial Settlement of 1690’, ibid., xx (1977), 59-76.

- T. C. Barker, ‘Smuggling in the Eighteenth Century: The Evidence of the Scottish Tobacco Trade’, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, !xii (1954), 387-99; W. A. Cole, ‘Trends in Eighteenth-Century Smuggling’, EcHR, x (1958), 395-410; H. C. and L. H. Mui, “Trends in Eighteenth-Century Smuggling” Reconsidered’, ibid., xxviii (1975), 28-43, with Cole’s rejoinder following, pp. 44-9.

- 0. M. Dickerson, The Navigation Acts and the American Revolution (Philadelphia, 1951). Slightly less optimistic estimates were offered by L. A. Harper, ‘The Effects of the Navigation Acts on the Thirteen Colonies’, in R. B. Morris (ed.), The Era of the American Revolution (New York, 1939), 3-39, and by C. P. Nettels, ‘British Mercantilism and the Economic Development of the Thirteen Colonies’, JEcH, xii (1952), 105-14.

- R. P. Thomas, ‘A Quantitative Approach to the Study of the Effects of British Imperial Policy upon Colonial Welfare: Some Preliminary Findings’, JEcH, xxv (1964), 615-38 launched the new examinations. R. L. Ransom, ‘British Policy and Colonial Growth: Some Implications of the Burden from the Navigation Acts’ JEcH, xxviii (1968), 427-35; P. McClelland, The Cost to America of British Imperial Policy’, American Economic Review, lix (1969), 370–81; and G. M. Walton, ‘The New Economic History and the Burdens of the Navigation Acts’, EcHR, xxiv (1971), extended, challenged, and refined the Thomas argument. McClelland and Walton had another exchange in ibid., xxvi (1973), 679-88.

- Watkins, foe. cit.; W. W. Rostow, The Process of Economic Growth (Oxford, 1953) and The World Economy (London, 1978); J. A. Ernst and M. Egnal, ‘An Economic Interpretation of the American Revolution’, W&MQ, xxix (1972), 3-32 and M. Egnal, ‘The Economic Development of the Thirteen Continental Colonies,1720–1775’, ibid., xxxii (1975), 191-222; North and Thomas, foe. cit. and The Rise of the Western World (Cambridge, 1974).

- J. 0. Appleby, Economic Thought and Ideology in Seventeenth-Century England (Princeton, 1978), 53.

- S. Diamond, ‘Values as an Obstacle to Economic Growth: The American Colonies’, JEcH, xxvii (1967), 561-75 and R. D. Brown, Modernization: The Transformation of American Life 1600-1865 (New York, 1976).